Abstract

Purpose

Although hypoxia is a known prognostic factor, its impact will be modified by the rate of reoxygenation and the extent to which cells are acutely hypoxic. We tested the ability of exogenous and endogenous markers to detect reoxygenation in a xenograft model. Our technique may be applicable to stored patient samples.

Methods and Materials

The human colorectal carcinoma line, HT29 was grown in nude mice. Changes in tumor hypoxia were examined by injection of pimonidazole followed 24 hours later by EF5. Cryosections were stained for these markers and for CAIX and HIF1α. Tumor hypoxia was artificially manipulated by carbogen exposure.

Results

In unstressed tumors, all four markers showed very similar spatial distributions. After carbogen treatment, pimonidazole and EF5 could detect decreased hypoxia. HIF1α staining was also decreased relative to CAIX, though the effect was less pronounced than for EF5. Control tumors displayed small regions that had undergone spontaneous changes in tumor hypoxia, as judged by pimonidazole relative to EF5; most of these changes were reflected by CAIX and HIF1α

Conclusions

HIF1α can be compared to either CAIX or a previously administered nitroimidazole to provide an estimate of reoxygenation.

Keywords: EF5, pimonidazole, carbonic anhydrase IX, hypoxia inducible factor 1α, reoxygenation

Introduction

Tumor hypoxia has an important influence on the outcome of therapy (reviewed in Ref. (1)). It is primarily known for its ability to reduce the effectiveness of radiation (2), but it can also moderate certain chemotherapeutic agents (3). Moreover, survival of patients undergoing surgery alone has also been shown to be negatively correlated with hypoxic status (4), and hypoxia is known to induce genes that confer metastatic ability (5, 6). Treatments devised to target hypoxic cells include carbogen delivered with radiotherapy (7); bioreductive drugs, acting either as cytotoxins or as radiosensitizers (8); and anaerobic bacteria that can target anoxic tumor tissue (9).

However, the extent of tumor hypoxia varies greatly from one individual to the next (10). Evaluating the success of any hypoxia-targeting strategy requires identifying patients with susceptible, i.e. hypoxic tumors. Hypoxic radiosensitizers of the 2-nitroimidazole family have made only slight improvements to therapeutic outcome (11), but the effect of these agents is probably underestimated, since the trials were conducted without regard to the hypoxic status of the tumors (12).

Tumor hypoxia is detected by a number of methods. Nitroimidazole based drugs accumulate in hypoxic cells. They can either be detected immunohistochemically or radiolabeled for PET or SPECT imaging (13). Direct measurements of tumor oxygen levels can be obtained from oxygen electrodes inserted into the tumor (10). Tumor hypoxia can also be inferred from the expression of various endogenous proteins. Hypoxia stabilizes HIF1α, leading to elevated levels of the protein and up-regulation of numerous HIF1-dependent genes (14). Of these, Glut1 and CAIX have been used most often as markers for hypoxia (15).

Elevated hypoxia often predicts a poor treatment outcome. In head and neck tumors, hypoxia as measured by electrodes is associated with poor local control (10, 16–18); in cervical cancer, it is associated with reduced survival (4, 19–21). Uptake of the nitroimidazoles EF5 and pimonidazole has also been shown to be prognostic (22–24). High expression of HIF1α and its targets CAIX and Glut 1 is also associated with treatment failure in numerous tumor types (25–34). Recently Koukourakis et al showed that high expression of CAIX and HIF2α were associated with radiotherapy failure in head and neck patients (35).

A second relevant variable is the rate of tumor reoxygenation. In the context of radiotherapy, hypoxia will be less of a problem in tumors that are rapidly reoxygenating, and animal studies suggest substantial differences in the rate of reoxygenation (2). Spontaneous reoxygenation, caused by the random opening and closing of tumor arterioles, leads to areas of acute hypoxia, in distinction to chronic hypoxia which occurs in regions where the nearest vessel is further away than the oxygen diffusion distance. Full radioresistance might only be a property of acutely hypoxic cells, as chronically hypoxic cells may down-regulate DNA repair enzymes (36). The predictive value of hypoxia may be increased if reoxygenation and acute hypoxia can be quantified.

Differences between HIF1α and CAIX expression may reflect changes in tumor hypoxia, since CAIX is a protein with a long half-life (37) which remains in cells after the inducing stress has been relieved. HIF1α in contrast is rapidly degraded in the presence of oxygen. In this context, it is interesting that Jankovic et al (38) found a good correlation between pimonidazole (administered 16 hours before biopsy) and CAIX, but poorer correlations between HIF1α and either CAIX or pimonidazole.

In this report, we have investigated the ability of CAIX and HIF1α to detect changes in tumor oxygenation. We compared these endogenous markers to pimonidazole and EF5, administered 24 hours apart, to test the hypothesis that HIF1α would reflect current hypoxia while CAIX would provide a historical record. Considering both spontaneous changes in tumor oxygenation observed in unstressed tumors, and artificially manipulated changes induced by carbogen treatment, we have found that changes in the uptake of EF5 relative to pimonidazole were mimicked by HIF1α and CAIX, albeit imperfectly. There is a practical reason for using HIF1α and CAIX in this way: namely the ability to analyze stored patient samples. Our results suggest that CAIX and HIF1α may be useful in detecting reoxygenation.

Methods and materials

Tumor model

The human colorectal carcinoma cell line HT29 was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained in exponential growth phase in McCoy’s 5A modified medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Xenografts were generated by subcutaneously injecting 5 × 106 tumor cells in 100μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the right hind limb of female immune-compromised NCI nu/nu mice (~20g, Frederick Cancer Research Institute, Frederick, MD). Experiments were performed when tumors reached 10–13 mm in diameter. The mice were maintained and used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Animal manipulation

Hydralazine (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride and injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 10 mg/kg 30 minutes prior to sacrifice. EF5 (provided by Dr CJ Koch), pimonidazole hydrochloride (Hypoxyprobe-1, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) were administered at 30, 120 and 50 mg/kg respectively. These agents were dissolved in PBS and administered via the tail vein. Hoechst was administered one minute before sacrifice by CO2 inhalation. The injection volumes were 0.2 ml (pimonidazole and EF5) and 0.1 ml (Hoechst 33342 and hydralazine).

Pimonidazole and EF5 were injected 24 hours and one hour before sacrifice, respectively, with the following two exceptions: In one experiment they were coinjected one hour prior to sacrifice. For hydralazine treatment, EF5 was injected 15 minutes before hydralazine administration, i.e. 45 minutes before sacrifice. For carbogen treatment, a cage of mice was placed in a sealed Perspex box (38 × 16 × 21 cm) with inlet and outlet vents. Carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2) was administered at a rate of 1 liter/minute. One hour before sacrifice, the mice were removed and injected with EF5. The mice were then returned to the box.

After the mice were sacrificed, the tumors were removed and frozen in OCT mounting medium (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Consecutive 10 μm thick sections were cut on a Microm HM500 cryostat microtome (Microm International GmbH, Walldorf, Germany). Each treatment group contained three to four mice.

Immunohistochemical staining and image acquisition

For EF5 and pimonidazole staining, sections were air-dried for 30 min and fixed in ice-cold methanol for 30 minutes. Hoechst images were acquired and sections were incubated in SuperBlock® (Pierce, Rockford, IL) overnight at 4°C. Cy3 conjugated anti-EF5 (supplied by Dr CJ Koch) was applied at a concentration of 75 μg/ml for six hours at 4°C. Slides were washed three times in PBS, and treated with sheep anti-cyanine (25 μg/ml, US Biologicals, Marblehead, MA) in mouse serum/Superblock (1:1) for one hour at room temperature. Slides were washed again and simultaneously exposed to FITC-conjugated anti-pimonidazole (1:20, Chemicon) and Alexafluor 568 anti-sheep (InVitrogen, Carlsbad CA) at 100 μg/ml in Superblock. Slides were washed three times and imaged on a fluorescent microscope.

For CAIX and HIF1α staining, sections were washed quickly in PBS, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 12 minutes, and quickly washed again. Sections were permeablized in 0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St Louis MO) for five minutes, washed for five minutes in PBS, and incubated for 30 minutes with Image-IT™ FX Signal Enhancher (InVitrogen). Slides were washed three times for five minutes in PBS and blocked with 90% SuperBlock®, 9% BSA, and 1% mouse serum for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were incubated with anti-CAIX, (humanized anti-CAIX monoclonal antibody, cG250, (39) a gift of Dr. Divgi, MSKCC) at 25 μg/ml in blocking buffer, for 1 hour at room temperature, washed three times for five minutes with blocking buffer, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 anti-human (Invitrogen) at 10 μg/ml in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were then washed three times for five minutes in PBS and rinsed in deionized water.

HIF1α staining was performed by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Molecular Cytology Core Facility. Slides were processed using the Discovery XT processor from Ventana Medical Systems (Tucson, AZ) and the tissue sections were blocked for 10 min in 10% normal goat serum, 2% BSA in PBS, followed by 12 minutes avidin/biotin block (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). HIF1α rabbit polyclonal antibody (Chemicon) was applied for three hours at 12 μg/ml, followed by 1 hour incubation with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, (Vector). The detection was performed with streptavidin horseradish peroxidase D (Ventana Medical Systems), followed by incubation with Tyramide-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). Slides were then imaged for HIF1α and CAIX on a fluorescent microscope.

Image acquisition and analysis

Images were acquired at 50x magnification using a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200M; Zeiss, Peabody, MA) equipped with a Coolsnap cooled charge-coupled device digital camera (Photometrics, Tuscon, AZ), a computer-controlled motorized stepping stage and Metamorph 7.0 Imaging software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Composite images of sections were stitched by Metamorph from individual microscopic images. Images were saved in 8 bit format for analysis in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA)

Necrosis could be easily recognized on the fluorescent images and these areas were excluded from analysis. From each image, viable tissue was selected in Photoshop and the histogram of the appropriate channel (red or green) was obtained. Image brightness was then adjusted in Photoshop so that the median brightness of the appropriate channel always corresponded to the arbitrarily chosen value of 60. This manipulation shifts the histogram to the left or right, without distorting its shape. The median value always corresponded to background staining, except in the case of EF5 uptake after hydralazine treatment, where most of the sections stained positive for the marker. In this case, small unstained areas of the sections were identified, and the median brightness of these areas obtained. Brightness of the whole section was then adjusted to bring the brightness of the unstained areas to 60. For binary analysis, all images were thresholded using an arbitrarily chosen value of 80 (1.33 × background) to obtain the area positive for each marker. We extended this analysis to encompass a range of threshold values as follows.

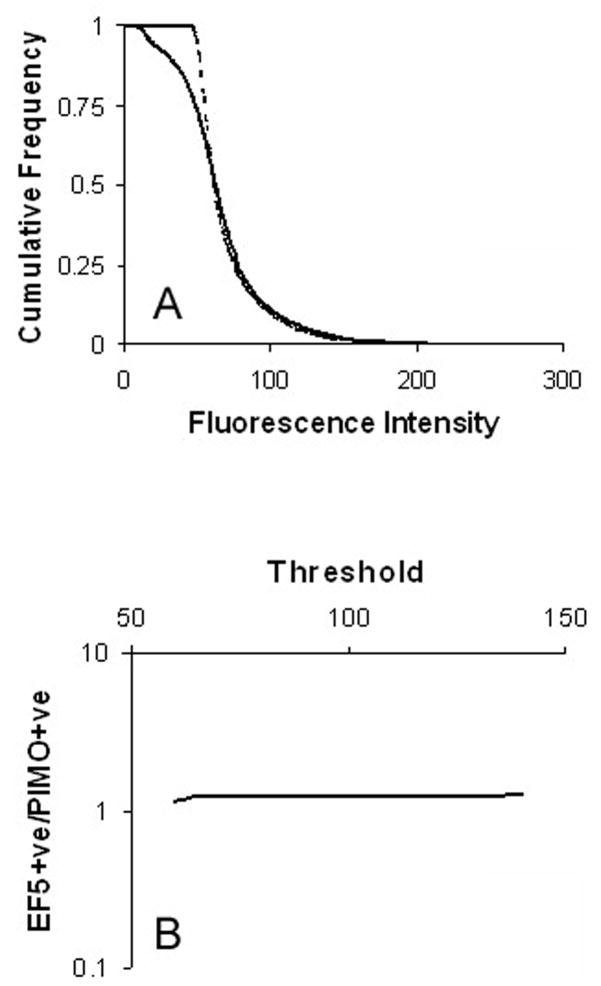

Using the Optipix Wide Histogram plugin (Reindeer Graphics, Ashville NC), the histograms of fluorescent intensity were exported to Excel where they were converted into cumulative form (Fig. 1A). Images of hypoxia markers are frequently analyzed by applying a threshold, and obtaining the positive fraction defined as the fraction of pixels greater than the threshold. Cumulative histograms show how the positive fraction would change as a function of the threshold. Further, it is possible to calculate the ratio of the fraction staining positive for marker 1 compared to marker 2 for each threshold value, as shown in Fig. 1B. This calculation was performed over the threshold range 60–140. We consider values outside of this range irrelevant since i) pixels with a value of 60 or below are always background, and ii) a threshold value of 140 treats pixels that are clearly positive (they have a brightness more than twice that of background) as negative for marker. This process was applied to all tumors in each treatment group, so that for every threshold value we obtained the mean ratio and 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 1.

(A) Cumulative histograms from a control section stained for EF5 (solid line) and pimonidazole (broken line). (B) The ratio of EF5 to pimonidazole can be collected for each fluorescence intensity. Data is shown on a log scale since this is required in subsequent plots to accommodate the range of values associated with carbogen and hydralazine treatments.

We identified regions of untreated tumors where EF5 and pimonidazole were clearly mismatched. These were overlaid in Photoshop with the adjacent images of HIF1α and CAIX. Three independent observers (acknowledged above) reported on whether the EF5/pimonidazole discrepancy was reflected by HIF1α and CAIX. Scoring was based on the majority opinion. The same process was repeated with regions where a mismatch between HIF1α and CAIX was observed.

Statistics

Differences between treatment groups were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test in Excel. A p value equal to or less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Colocalization of markers in unstressed tumors

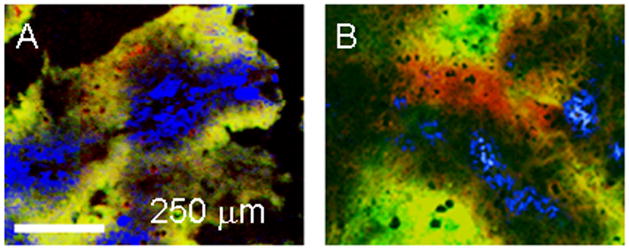

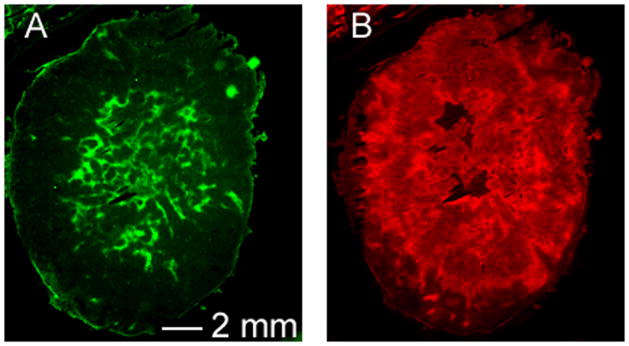

In the following images, EF5 and CAIX are stained red; pimonidazole and HIF1α are green. When EF5 and pimonidazole were co-injected, there was almost complete agreement between the two markers, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. When the markers were separated by 24 hours, with pimonidazole being given first, the agreement was reduced – pimonidazole was further away from the neighboring blood vessels than EF5. The pimonidazole labeled cells were presumably being pushed away from the blood vessels by proliferating cells. Newly hypoxic tissue is visible as red, i.e. positive for EF5 but not pimonidazole. This is shown in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 2.

Tumors from animals given pimonidazole and EF5. (A) Drugs coadministered; (B) pimonidazole followed 24 hours later by EF5. Pimonidazole was stained green, EF5, red. Yellow represents double staining. Perfused vessels are stained blue.

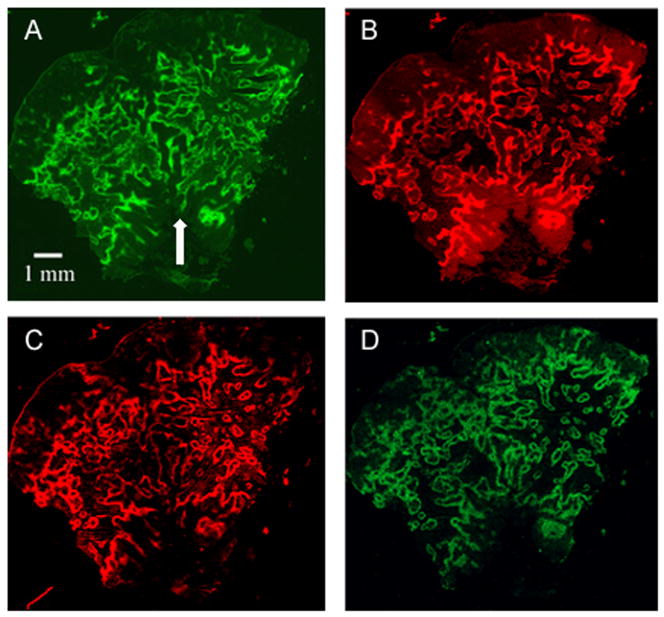

Figure 3 shows images of a control tumor stained for all four markers. Pimonidazole was given 24 hours before EF5. Much of the staining is concentrated round necrotic tissue and regions that are positive for pimonidazole are generally positive for EF5. CAIX and HIF1α were also in good agreement with each other and with pimonidazole and EF5. To further investigate the markers, we artificially manipulated tumor oxygenation through treating the mice with carbogen. We expected that CAIX would track pimonidazole, and HIF1α would follow EF5.

Fig. 3.

Control tumor stained for (A) pimonidazole, (B) EF5, (C) CAIX, and (D) HIF1α. The arrow indicates a feature shown in detail in figure 7A/B.

Effect of carbogen treatment on marker distribution

As shown in Figs. 4A and B, when mice were exposed to carbogen for two hours before sacrifice, it resulted in a dramatic drop of EF5 uptake relative to pimonidazole (EF5 was injected one hour after the start of carbogen exposure). There was also a reduction in HIF1α relative to CAIX. However HIF1α staining was not uniformly removed by carbogen. (Figs. 4C and D). It may be that HIF1α staining is due to intermediate hypoxia, since HIF1α can be detected at oxygen levels of 1.5% (40), considerably greater than is consistent with EF5 binding.

Fig. 4.

Mice were injected with pimonidazole prior to, and with EF5 during a two hour carbogen exposure: (A) pimonidazole, (B) EF5, (C) CAIX, (D) HIF1α.

We also used hydralazine treatment to generate newly hypoxic regions. As expected, increasing hypoxia by hydralazine treatment led to significantly increased EF5 uptake relative to pimonidazole (Figs. 5A and B). The likely mechanism is that the drug is first trapped in the tumor tissue as the tumor’s blood supply fails, and that under the resultant hypoxia it is then bound to macromolecules. We have previously shown in HT29 tumors that 30 minutes after hydralazine exposure tumor perfusion is lost (41). However, 30 minutes is insufficient for HIF1α induction, and we could not reliably maintain tumors in a hypoxic state by repeated use of hydralazine.

Fig. 5.

The effects of hydralazine 30 minutes after treatment. (A) pimonidazole, (B) EF5

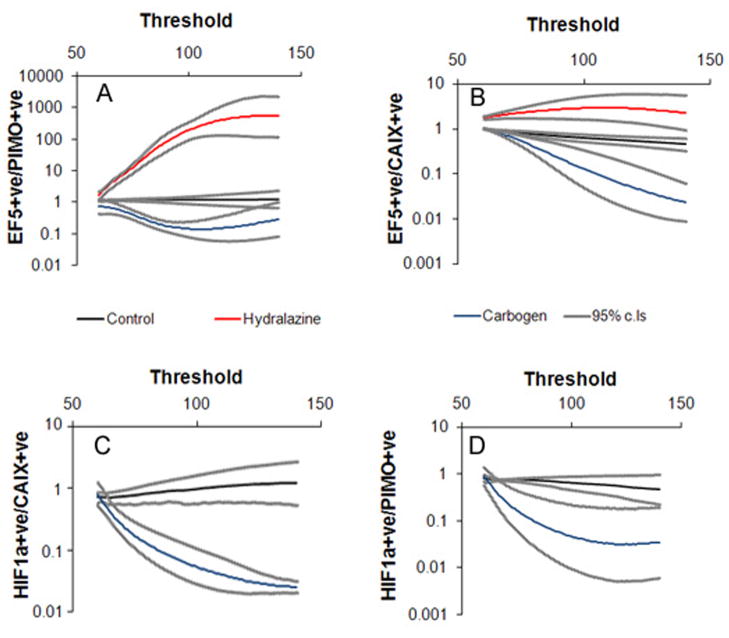

Quantitation of staining intensity

We quantified the changes in marker intensity in two ways. We applied the commonly used thresholding technique (42) to our images, using a threshold value of 80 or 33% above background to all images. Images analyzed with a threshold give a “positive fraction” – the area of the section that stains brighter than the selected threshold value. The results are shown in table 1. For control tumors, EF5 did not differ significantly from pimonidazole, nor did HIF1α differ from CAIX. Both carbogen and hydralazine treatments led to a significant increase in EF5 relative to pimonidazole. There was also a significant decrease in HIF1α relative to CAIX after carbogen treatment. With this method, it is not always clear whether the same results would be obtained if a different threshold were selected. To avoid this problem, rather than choose a single threshold, for each marker we obtained the positive fraction over a wide range of thresholds. We then plotted the ratio of various pairs of markers as a function of the threshold value, over this range. For each image, the median pixel intensity was set to 60 – this represents the background value. Adjusting the brightness settings in this way shifts the histograms to the left or right, but does not distort their shape. With the images having the same background intensity, it is possible to apply the same threshold to matched images (e.g. EF5 and pimonidazole), and derive a ratio of the positive fractions, as well as associated confidence intervals. In this way, the treated sections can be compared to the controls at every relevant threshold setting. Figure 5 shows the results of this analysis. For control sections, the ratio of EF5 to pimonidazole (Fig. 6A) did not differ significantly from one, over the examined threshold range. In other words, no matter what threshold was selected, both pimonidazole and EF5 would give the same positive fraction. After two hours of carbogen treatment, the ratio of EF5 to pimonidazole was significantly less than the controls at almost all threshold values, while hydralazine treatment significantly increased the EF5/pimonidazole ratio relative to the controls. It should be noted that at high threshold values the results are less meaningful because so much of the section is deemed negative for marker. The same pattern is repeated when EF5 is compared to CAIX (Fig. 6B). Figures 6C and D show how HIF1α relates to CAIX and pimonidazole, respectively. Thus the changes reported in table 1 are threshold independent –every significant change reported in table 1 would be significant at any threshold setting.

Table 1.

Binary analysis of the sections.

| Fraction positive for: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pimonidazole (mean ± SD) | EF5 | CAIX | HIF1α | |

| Control | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.04* | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.17 ± 0.02‡ |

| Carbogen | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.06 ± 0.009† | 0.19 ± 0.08 | 0.03 ± 0.02§ |

| Hydralazine | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.18† | 0.28 ± 0.02 | n.a. |

Not significantly different from pimonidazole;

significantly different from pimonidazole;

not significantly different from CAIX;

significantly different from CAIX; HIF1α and CAIX staining not performed on sections from hydralazine treated mice. n.a. not appropriate.

Fig. 6.

Quantifying marker binding. (A) The fraction of the section area staining positive for EF5 is expressed relative to the fraction staining positive for pimonidazole. The plot shows how this value depends on the threshold used to define positive staining. The same procedure was undertaken for EF5/CAIX (B). HIF1α/CAIX is shown in (C) and HIF1α/pimonidazole in (D). Hypoxia could not be artificially maintained for a time long enough to allow detectable HIF1α accumulation, so that changes in HIF1α could only be analyzed after carbogen treatment. Control/hydralazine n=4; carbogen n = 3

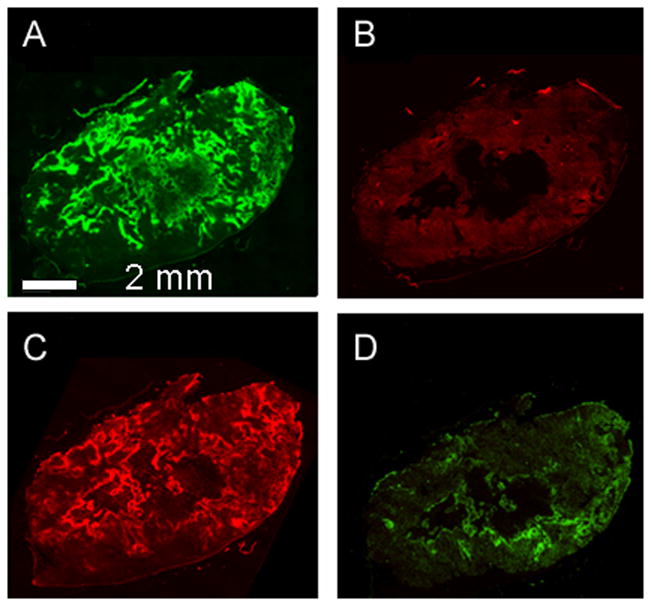

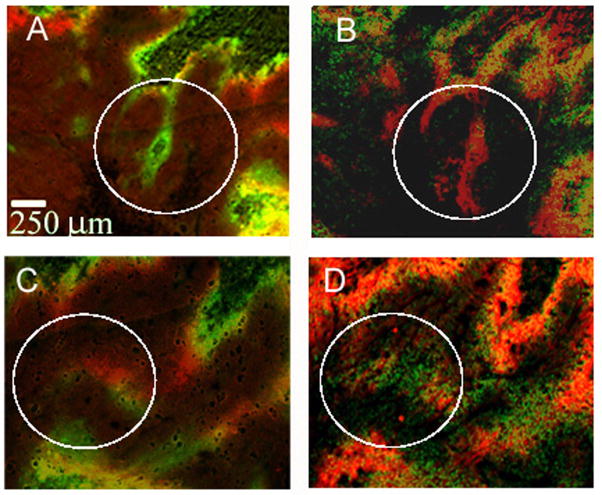

Spontaneous changes in tumor oxygenation

Spontaneous changes in oxygenation in untreated tumors have been reported by Bennewith and Durand (43). We studied a total of 14 untreated tumors, looking for regions where there were mismatches in pimonidazole and EF5 binding. We then examined the corresponding areas in adjacent slides stained for CAIX and HIF1α Figures 7A and C show the overlap of pimonidazole and EF5 in two such regions. In Fig. 7A, there is a small area where hypoxia has been lost, as judged by the presence of pimonidazole alone. In the corresponding CAIX/HIF1α image (Fig. 7B), this object appears stained for CAIX, but not HIF1α. In Fig. 6C, a region of new hypoxia can be detected, where EF5 bound in the absence of pimonidazole, and this is reflected in Fig. 7D, where HIF1α is present without detectable CAIX. Such regions were always small, with the average area estimated as 6 × 104 μm2 or 0.1% of the tumor’s viable area. We also repeated the search in reverse, looking first at CAIX/HIF1α and then at pimonidazole/EF5. In total, we identified 31 areas in these tumors where at least one set of markers suggested a change in tumor oxygenation. The results are summarized in table 2. Twenty five areas showed a difference between EF5 and pimonidazole; in 18 of these regions this change was paralleled by CAIX and HIF1α. There were also six areas where CAIX/HIF1α implied a change that could not be detected by pimonidazole/EF5.

Fig. 7.

Changes in hypoxia reflected by both sets of markers. (A) Pimonidazole overlaid on EF5. The green area represents a loss of hypoxia in the interval between marker administration. (B) The corresponding area of adjacent slides stained for CAIX and HIF1α A) and (B) come from the marked area of figure 3. (C) Pimonidazole overlaid on EF5. The red area represents a gain of hypoxia in the interval between marker administration. (D) The corresponding area of adjacent slides stained for CAIX and HIF1α.

Table 2.

Ability of CAIX and HIF1α to detect spontaneous changes in tumor oxygenation.

| Change in hypoxia | Number of regions where a change could be detected by: | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PIMO/EF5 & CAIX/HIF1α | PIMO/EF5 alone | CAIX/HIF1α alone | |

| Gain | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| Loss | 11 | 5 | 2 |

Discussion

Using the HT29 model, we have found that pimonidazole and EF5 are almost identically distributed when co-administered, and only minimally different when given 24 hours apart. Artificially inducing tumor hypoxia while EF5 was present in the animal led to a visible increase in EF5 relative to pimonidazole, while oxygenating the tumor through carbogen exposure led to greatly reduced EF5 binding relative to pimonidazole. These changes were visible from inspection of the immunofluorescent images. However, we have also quantified these differences between control and treated tumors and shown that they were statistically significant, and that the significance was not dependent on a given threshold value. These results resemble those of Ljungkvist et al, who have previously shown that double labeling with pimonidazole and CCI-103F can be used to detect changes in tumor oxygenation including those produced by carbogen and hydralazine (44–46).

Our object here was to assess whether the CAIX/HIF1α pairing could also yield information on changes in tumor hypoxia. This requires that CAIX and HIF1α should primarily indicate tumor hypoxia, here defined by nitroimidazole binding. Although CAIX was initially hailed as a promising marker for tumor hypoxia based on animal (47, 48) and patient studies (38, 49, 50), its value has recently been called into question. In a xenograft model, Troost et al (51) found it significantly under-represented hypoxia, relative to pimonidazole, and in patients with adenocarcinoma, CAIX and pimonidazole only co-localized in 30% of cases (52). Van Laarhoven et al found no correlation between pimonidazole and CAIX intensity in liver metastases, though importantly they did find co-localization of the two markers (53). They also found areas of mismatch between the markers, which could be due to changing hypoxia. As the literature stands, it seems that CAIX is an unreliable guide to hypoxia. We would note however that some of the discrepancy between CAIX and pimonidazole may be due to changes in tumor oxygenation, and that the value of CAIX would be more accurately assessed if it was compared against two exogenous markers.

There are several reasons why HIF1α and its downstream genes might fail to match the nitroimidazoles. It is induced at relatively high oxygen concentrations (≈ 1.5%, (40) and moreover its expression is influenced by non-hypoxic factors, including low pH and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K/AKT) pathway (54, 55). However, low pH is associated with low pO2 (56), and PI3K activity is unlikely to show any spatial variation.

We found in control HT29 tumors that pimonidazole, EF5, HIF1α and CAIX all yielded similar maps of the spatial distribution of hypoxia. The ability of the endogenous markers to detect reoxygenation comes because HIF1α levels fall rapidly as tissue becomes oxygenated, while CAIX changes very slowly. One would not expect these markers to be as good at detecting new hypoxia, since the time window is much narrower – a discrepancy between HIF1α and CAIX will exist only for as long as is required for transcription and translation of CAIX.

We were able to demonstrate the ability of CAIX/HIF1α to detect reoxygenation after carbogen treatment. However, as can be seen in figure 4, the effect of carbogen on HIF1α levels was less pronounced than on EF5. This may be due to the fact that at moderate hypoxia, HIF1α is strongly induced while EF5 binding is weak (40, 57). Whatever the cause, it seems that HIF1α may well underestimate the extent of reoxygenation, and overestimate the radiobiological hypoxic fraction, since radiobiological hypoxia is most marked over the range of 0 – 0.5% O2 (2).

We also found that CAIX/HIF1α could detect spontaneous changes in tumor hypoxia. Close inspection of control tumors revealed both regions where there was high pimonidazole but only minimal EF5, representing a loss of hypoxia, and conversely areas of new hypoxia, identified by low pimonidazole and high EF5. In 18 out of 25 cases these changes were reflected in the staining pattern of CAIX/HIF1α CAIX/HIF1α seemed as good at detecting new hypoxia as reoxygenation, though as discussed above one would expect them to be less efficient at detecting such events. In these experiments the new hypoxia is never more than 24 hours old. Presumably, most of these events have occurred too recently for CAIX levels to rise significantly. There were also six areas where discrepancies existed between CAIX and HIF1α that had no counterpart in the pimonidazole/EF5 images. Speculatively, this may be due to changes in oxygenation occurring, but at higher oxygen levels than would trigger pimonidazole/EF5 binding; or to a failure of one of the endogenous markers to reach hypoxic tissue, since in these areas there was a total absence of either pimonidazole or EF5.

Considering the results in total, we conclude that in this system HIF1α and CAIX would provide an acceptable guide to changes in tumor hypoxia.

Acknowledgments

Grants: This work was funded by NIH-NCI PO1CA115675-A1. This publication acknowledges Grant Number NCI P30-CA 08748, which provides partial support for the Research Animal Resource Center. KMY was supported by funds from the Korean Cancer Research Institute.

The authors would like to thank Professor CJ Koch, University of Pennsylvania for his thoughtful reading of this manuscript, and Drs P Burgman, XF Li and XR Sun of MSKCC for image assessment.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest notification

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest regarding the contents of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall E, Giacca A. Radiobiology for the Radiologist. 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song X, Liu X, Chi W, et al. Hypoxia-induced resistance to cisplatin and doxorubicin in non-small cell lung cancer is inhibited by silencing of HIF-1alpha gene. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58:776–784. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hockel M, Schlenger K, Aral B, et al. Association between tumor hypoxia and malignant progression in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4509–4515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiraga T, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Hirota K, et al. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 expression enhance osteolytic bone metastases of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4157–4163. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rofstad EK, Danielsen T. Hypoxia-induced metastasis of human melanoma cells: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1697–1707. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaanders JHAM, Bussink J, van der Kogel AJ. ARCON: a novel biology-based approach in radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:728–737. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffar M, Williams KJ, Stratford IJ. Bioreductive and gene therapy approaches to hypoxic diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bettegowda C, Dang LH, Abrams R, et al. Overcoming the hypoxic barrier to radiation therapy with anaerobic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15083–15088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036598100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brizel DM, Sibley GS, Prosnitz LR, et al. Tumor hypoxia adversely affects the prognosis of carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overgaard J. Clinical evaluation of nitroimidazoles as modifiers of hypoxia in solid tumors. Oncol Res. 1994;6:509–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overgaard J, Horsman MR. Modification of Hypoxia-Induced Radioresistance in Tumors by the Use of Oxygen and Sensitizers. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1996;6:10–21. doi: 10.1053/SRAO0060010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman JD, Engelhardt EL, Stobbe CC, et al. Measuring hypoxia and predicting tumor radioresistance with nuclear medicine assays. Radiother Oncol. 1998;46:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Airley RE, Loncaster J, Raleigh JA, et al. GLUT-1 and CAIX as intrinsic markers of hypoxia in carcinoma of the cervix: relationship to pimonidazole binding. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:85–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brizel DM, Dodge RK, Clough RW, et al. Oxygenation of head and neck cancer: changes during radiotherapy and impact on treatment outcome. Radiother Oncol. 1999;53:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordsmark M, Overgaard J. A confirmatory prognostic study on oxygenation status and loco-regional control in advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated by radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2000;57:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordsmark M, Overgaard J. Tumor hypoxia is independent of hemoglobin and prognostic for loco-regional tumor control after primary radiotherapy in advanced head and neck cancer. Acta Oncol. 2004;43:396–403. doi: 10.1080/02841860410026189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fyles A, Milosevic M, Hedley D, et al. Tumor hypoxia has independent predictor impact only in patients with node-negative cervix cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:680–687. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hockel M, Knoop C, Schlenger K, et al. Intratumoral pO2 predicts survival in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Radiother Oncol. 1993;26:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knocke TH, Weitmann HD, Feldmann HJ, et al. Intratumoral pO2-measurements as predictive assay in the treatment of carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Radiother Oncol. 1999;53:99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans SM, Fraker D, Hahn SM, et al. EF5 binding and clinical outcome in human soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:922–927. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans SM, Judy KD, Dunphy I, et al. Hypoxia is important in the biology and aggression of human glial brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8177–8184. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaanders JH, Wijffels KI, Marres HA, et al. Pimonidazole binding and tumor vascularity predict for treatment outcome in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7066–7074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aebersold DM, Burri P, Beer KT, et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha: a novel predictive and prognostic parameter in the radiotherapy of oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2911–2916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chia SK, Wykoff CC, Watson PH, et al. Prognostic significance of a novel hypoxia-regulated marker, carbonic anhydrase IX, in invasive breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3660–3668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths EA, Pritchard SA, Valentine HR, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression in the gastric carcinogenesis sequence and its prognostic role in gastric and gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:95–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawamura T, Kusakabe T, Sugino T, et al. Expression of glucose transporter-1 in human gastric carcinoma: association with tumor aggressiveness, metastasis, and patient survival. Cancer. 2001;92:634–641. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<634::aid-cncr1364>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kon-no H, Ishii G, Nagai K, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX expression is associated with tumor progression and a poor prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunkel M, Reichert TE, Benz P, et al. Overexpression of Glut-1 and increased glucose metabolism in tumors are associated with a poor prognosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1015–1024. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loncaster JA, Harris AL, Davidson SE, et al. Carbonic anhydrase (CA IX) expression, a potential new intrinsic marker of hypoxia: correlations with tumor oxygen measurements and prognosis in locally advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6394–6399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuyama T, Nakanishi K, Hayashi T, et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trastour C, Benizri E, Ettore F, et al. HIF-1alpha and CA IX staining in invasive breast carcinomas: prognosis and treatment outcome. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1451–1458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Younes M, Brown RW, Stephenson M, et al. Overexpression of Glut1 and Glut3 in stage I nonsmall cell lung carcinoma is associated with poor survival. Cancer. 1997;80:1046–1051. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970915)80:6<1046::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koukourakis MI, Bentzen SM, Giatromanolaki A, et al. Endogenous markers of two separate hypoxia response pathways (hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha and carbonic anhydrase 9) are associated with radiotherapy failure in head and neck cancer patients recruited in the CHART randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:727–735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bindra RS, Schaffer PJ, Meng A, et al. Down-regulation of Rad51 and decreased homologous recombination in hypoxic cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8504–8518. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8504-8518.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rafajova M, Zatovicova M, Kettmann R, et al. Induction by hypoxia combined with low glucose or low bicarbonate and high posttranslational stability upon reoxygenation contribute to carbonic anhydrase IX expression in cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:995–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jankovic B, Aquino-Parsons C, Raleigh JA, et al. Comparison between pimonidazole binding, oxygen electrode measurements, and expression of endogenous hypoxia markers in cancer of the uterine cervix. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2006;70:45–55. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steffens MG, Boerman OC, Oosterwijk-Wakka JC, et al. Targeting of renal cell carcinoma with iodine-131-labeled chimeric monoclonal antibody G250. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1529–1537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang BH, Semenza GL, Bauer C, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 levels vary exponentially over a physiologically relevant range of O2 tension. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1172–1180. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin KH, Diaz-Gonzalez JA, Russell J, et al. Detecting Changes in Tumor Hypoxia with Carbonic Anhydrase IX and Pimonidazole. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:70–75. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.1.3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Laarhoven HWM, Bussink J, Lok J, et al. Effects of nicotinamide and carbogen in different murine colon carcinomas: Immunohistochemical analysis of vascular architecture and microenvironmental parameters. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennewith KL, Durand RE. Quantifying transient hypoxia in human tumor xenografts by flow cytometry. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6183–6189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ljungkvist AS, Bussink J, Kaanders JH, et al. Hypoxic cell turnover in different solid tumor lines. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1157–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ljungkvist AS, Bussink J, Kaanders JH, et al. Dynamics of hypoxia, proliferation and apoptosis after irradiation in a murine tumor model. Radiat Res. 2006;165:326–336. doi: 10.1667/rr3515.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ljungkvist AS, Bussink J, Rijken PF, et al. Changes in tumor hypoxia measured with a double hypoxic marker technique. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1529–1538. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sobhanifar S, Aquino-Parsons C, Stanbridge EJ, et al. Reduced expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in perinecrotic regions of solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7259–7266. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubois L, Landuyt W, Haustermans K, et al. Evaluation of hypoxia in an experimental rat tumour model by [(18)F]fluoromisonidazole PET and immunohistochemistry. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1947–1954. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoskin PJ, Sibtain A, Daley FM, et al. GLUT1 and CAIX as intrinsic markers of hypoxia in bladder cancer: relationship with vascularity and proliferation as predictors of outcome of ARCON. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hutchison GJ, Valentine HR, Loncaster JA, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression as an intrinsic marker of hypoxia: correlation with tumor oxygen, pimonidazole measurements, and outcome in locally advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8405–8412. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Troost EG, Bussink J, Kaanders JH, et al. Comparison of different methods of CAIX quantification in relation to hypoxia in three human head and neck tumor lines. Radiother Oncol. 2005;76:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goethals L, Debucquoy A, Perneel C, et al. Hypoxia in human colorectal adenocarcinoma: comparison between extrinsic and potential intrinsic hypoxia markers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Laarhoven HW, Kaanders JH, Lok J, et al. Hypoxia in relation to vasculature and proliferation in liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ihnatko R, Kubes M, Takacova M, et al. Extracellular acidosis elevates carbonic anhydrase IX in human glioblastoma cells via transcriptional modulation that does not depend on hypoxia. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Majumder PK, Febbo PG, Bikoff R, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Helmlinger G, Yuan F, Dellian M, et al. Interstitial pH and pO2 gradients in solid tumors in vivo: high-resolution measurements reveal a lack of correlation. Nat Med. 1997;3:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koch CJ, Evans SM, Lord EM. Oxygen dependence of cellular uptake of EF5 [2-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoropropyl)a cet amide] : analysis of drug adducts by fluorescent antibodies vs bound radioactivity. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:869–874. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]