Abstract

Degranulation of mast cells in response to antigen (Ag) or the calcium mobilizing agent, thapsigargin, is dependent on emptying of intracellular stores of Ca2+ and the ensuing influx of external Ca2+, also referred to as store-operated calcium entry (SOCE). However, it is unlikely that the calcium release-activated calcium current (CRAC) is the sole mechanism for the entry of Ca2+ because Sr2+ and other divalent cations also permeate and support degranulation in stimulated mast cells. Here we show that influx of Ca2+ and Sr2+ as well as degranulation are dependent on the presence of the transient receptor potential channel canonical 5 (TRPC5), in addition to STIM1 and Orai1, as demonstrated by knock down of each of these proteins by inhibitory RNAs in a rat mast cell (RBL-2H3) line. Overexpression of STIM1 and Orai1, which are known to be essential components of CRAC, allows entry of Ca2+ but not Sr2+ whereas overexpression of STIM1 and TRPC5 allows entry of both Ca2+ and Sr2+. These and other observations suggest that Sr2+-permeable TRPC5 associates with STIM1 and Orai1 in a stoichiometric manner to enhance entry of Ca2+ to generate a signal for degranulation.

An increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels in mast cells provides an essential signal for exocytotic release of granules whether cells are stimulated via the IgE receptor (FcεRI) or thapsigargin (1, 2). The increase in cytosolic Ca2+ is associated with release from intracellular stores and influx of external Ca2+ (3, 4) by a mechanism, originally referred to as capacitative calcium entry (CCE) but now often referred to as store-operated calcium entry (SOCE), in which depletion of intracellular stores of Ca2+ leads to entry of Ca2+ (5, 6). Ca2+-entry was initially thought to occur through a calcium-release activated calcium current (ICRAC or CRAC) that was first identified in mast cells by patch-clamp techniques (7, 8). CRAC is a Ca2+-selective current of low conductance that requires external Ca2+ to achieve maximal conductance. Replacement of Ca2+ with Sr2+ or Ba2+ results in a decline in CRAC activity (9, 10). Nevertheless, it appears unlikely that CRAC is the sole mechanism for conductance of Ca2+ as early studies of calcium-dependent exocytosis clearly demonstrated that stimulated mast cells become highly permeable to a variety of divalent cations including Sr2+, Ba2+, and Mn2+ and that such ions can support degranulation in the absence of Ca2+ (11-13).

Members of the subfamily of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, especially the TRP canonical (TRPC) channels, were initially considered as candidates for mediating SOCE (14, 15). The TRPCs are activated as a consequence of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate generated through phospholipase C (PLC). Some TRPCs, such as TRPC1 and TRPC4, are activated by store depletion via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate or thapsigargin as demonstrated in cells deficient in TRPC1 or TRPC4 (16) or by overexpression (14, 15, 17-19) or knock down (18, 20-25) of these proteins. TRPC5 may be regulated by a variety of signals including Ca2+-store depletion (26) although there are contrary reports (27, 28). On the basis of structure and function, TRPC1, 4, and 5 appear to form one category of TRPCs and TRPC3, 6, and 7 another (29). The latter category appears to be activated primarily by diacylglycerides (i.e. receptor-operated) rather than store depletion (30, 31). However, TRPCs can conduct divalent cations such Sr2+ and Ba2+ in addition to Ca2+ and none of the TRPCs appear to have the exact electrophysiological features of CRAC (32).

The molecular identity of CRAC has been clarified recently with the identification of two proteins, STIM1 a Ca2+sensor and Orai1 a channel protein, which are essential for CRAC activity. STIM1 was first identified as a component of CRAC in Drosophila S2 cells and Jurkat T cells by use of inhibitory RNAs (33). Of the two known mammalian homologues (STIM1 and STIM2), STIM1 appears to be the primary sensor of Ca2+ in intracellular stores in mammalian cells (33-37). STIM1 is strategically located in the endoplasmic reticulum and knock down of STIM1, but not of STIM2, by siRNA abolishes SOCE and CRAC following Ca2+-store depletion. The second component of CRAC was identified as a mammalian homologue of Drosophila Orai (38) also referred to as CRACM (39). A key discovery was the presence of an inactivating mutation of Orai1 in a patient with severe immunodeficiency (SCID) that was associated with low CRAC activity in T cells (38, 40). Subsequent studies showed that coexpression of Orai1 and STIM1 dramatically enhanced CRAC and SOCE (41-43). A paradoxical and unexplained finding was that overexpression Orai1 by itself suppresses CRAC and SOCE. In addition, the electrophysiological features of coexpressed Orai1 and STIM1 did not match those originally described for CRAC, which left the possibility that additional molecules might be involved (32). Recent work now indicates that TRPCs may associate with STIM1 and Orai1 and thus alter channel properties as well as enhance Ca2+ entry (44-46).

We investigated the potential role of endogenous TRPCs in supporting entry of Ca2+ and Sr2+ as well as degranulation in a rat mast cell (RBL-2H3) line by overexpression or knock down of TRPCs, Orai1, and STIM1. As reported here, we found that, among the various TRPCs expressed in these cells, TRPC5 permitted influx of Sr2+, optimal influx of Ca2+, and degranulation. However, TRPC5 function was dependent on Orai1 and STIM to suggest that TRPC5 acted in conjunction with these two proteins.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Reagents were purchased from the following sources: media, culture reagents, and Platinum blue PCR SuperMix from Invitrogen/GIBCO (Carlsbad, CA); mouse monoclonal anti-DNP IgE, dinitrophenylated human serum albumin (DNP-HSA), and ρ-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-ß-D-glucosaminide from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); thapsigargin, 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol, U73122, and RHC80267 from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); antibodies against TRPC1, TRPC3, and TRPC5 from Alomone labs (Jerusalem, Israel) and against TRPC2 from Chemicon (Temecula, CA); TRPC7 antibody from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX); antibodies against Orai1 from ProSci Inc (Poway, CA); antibodies against STIM1 from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); Fura-2 AM ester from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Orai1 and STIM1 plasmids as well as HuSH 29mer shRNA constructs against Orai1, STIM1, and various TRPCs were obtained from Origene (Rockville, MD). Although all available shRNA constructs from Origene were tested, representative data are shown with the following constructs #TI548839, #TI100018, #TI502171, #TI304029, and #TI336191 to knock down TRPC1, TRPC5, TRPC7, Orai1, and STIM1, respectively. All other chemicals were molecular biology grade from several sources.

Anti-TRPC3 siRNA

The siRNA targeted against rat TRPC3 was generated with the Silencer™ Express Kit, pSEC™ neo (Ambion, Austin TX) and the following oligonucleotide (the target sequence was 541-561 of rat TRPC3, AB022331); sense oligonucleotide: 5'-GTGCTA CACAAACACACCTACTACGAAGTCTCGGTGTTTCGCCTTTCCACAAG-3' and antisense oligonucleotide: 5'-CGGCGAAGCTTTTTCCAAAAAAGACTTCGTAGTAGGTGTGCTACACAAACACA- 3', according to the manufacturer's instruction. A negative control siRNA was generated by using the oligonucleotides that were provided in the Silencer™ Express Kit.

Detection of mRNA for TRPCs by RT-PCR

RBL-2H3 cells (5 × 106 cells) were used for extraction of RNA as described elsewhere (47). The Advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was used to transcribe 1 μg RNA to cDNA, of which 1 μg was used for the PCR reaction with gene-specific primers for rat TRPC family members (48) (from Lofstrand Labs Limited, Gaithersburg, MD) and β-actin. PCR amplification was performed with Platinum Blue PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen) under the following conditions for 40 cycles: 30 sec at 94 °C (denature), 30 sec at 56 °C (anneal), 1 min at 72 °C (extend), and final extension at 10 min at 72 °C. Rat brain mRNA (Ambion, Austin, TX) was processed with the same protocol and was used as a positive control for TRPC expression.

Transient transfection, stimulation of cells, and immunoblotting

RBL-2H3 and the muscarinic m1 receptor-bearing RBL-2H3(m1) cells (49, 50) were cultured in complete growth medium as described previously (51). Cells were transiently transfected by electroporation (Cell Line Nucleofector Kit L, Amaxa transfection system) with the plasmids or inhibitory RNAs (1 μg/106 cells) along with the expression vector (pd2EYFP-N1, Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) that encodes enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) in the ratio of 5:1. Cells were examined 24 h or 48 h after transfection with the inhibitory RNAs or plasmids, respectively. Transfection efficiency ranged from 50% to 80%. Where necessary, cells were incubated overnight with IgE (50 ng/ml) to achieve 100% occupancy of FcεRI. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml Ag (DNP-HSA) or 1μM thapsigargin to achieve maximal responses. Immunoblotting of whole cell lysates were performed as described elsewhere (51).

Measurement of degranulation

Cells in 24 well plates (2×105 cells/0.4 ml/well) were washed and the medium replaced with a PIPES-buffered medium (25 mM PIPES, pH 7.2, 159 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 5.6 mM glucose, and 0.1% fatty acid-free fraction V from bovine serum) before stimulation. Where indicated, Ca2+ was omitted from the medium or 3 mM Sr2+ was substituted for Ca2+. Degranulation was determined by measurement of the release of the granule marker, ß-hexosaminidase, by use of a colorimetric assay in which release of p-nitrophenol from p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-ß-D-glucosaminide was measured (1). Values were expressed as the percentage of intracellularß-hexosaminidase that was released into the medium.

Imaging of Intracellular Calcium in Single Cells

After transfection, cells were grown on coverslips in complete growth medium for 48 h. Medium was then replaced with PIPES-buffered medium (see previous section) and loaded with Fura-2 AM (2 μM) for 25 min at 25 °C. Cells were washed, and the dye was allowed to de-esterify for a minimum of 15 min at 25 °C. The coverslips were placed in Ca2+-free PIPES-buffered medium and 1 mM CaCl2 or 3 mM SrCl2 was added as shown in the figures. Cytosolic Ca2+ was measured in individual transfected and non-transfected cells in the InCyt dual wavelength fluorescence imaging system (Intracellular Imaging Inc. Cincinnati, OH). EYFP served as the transfection marker in cells and was detected at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm. Non-transfected cells (not expressing EYFP) were identified from the same field and served as control cells. After cell identification, fluorescence emission at 505 nm was monitored with alternating excitation at wavelengths 340 and 380 nm. Relative intracellular content of divalent cation (Ca2+ or Sr2+) is depicted as the average ratio of fluorescence (340/380 nm) in 10-20 single transfected and non-transfected cells as described previously (52). All measurements shown are representative of three or more independent experiments.

Results and Discussion

Sr2+ entry is dependent on store depletion

Previous findings that Sr2+ can substitute for Ca2+ to support degranulation in stimulated RBL-2H3 cells (13) raise the possibility that Ca2+-conducting channels also conduct Sr2+. To examine whether or not entry of Sr2+, like Ca2+, is dependent on depletion of intracellular stores of Ca2+, we compared the effects of thapsigargin to those of Ag and the muscarinic agonist, carbachol, in RBL-2H3(m1) cells, a stably transfected cell line made to express the G protein-coupled muscarinic m1 receptor (49, 50). In contrast to thapsigargin which minimally stimulates PLC in RBL-2H3 cells (53), Ag and carbachol activate PLCγ (54) and PLCß (55), respectively. Both Ag and carbachol induced a transient Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores in the absence of external Ca2+ followed by Sr2+ or Ca2+ entry when either of these ions were added externally (Fig. 1A and B). Depletion of the intracellular Ca2+ stores by thapsigargin, which does so by blocking uptake of cytosolic Ca2+ into these stores (6), also induced Sr2+ and Ca2+ entry (Fig. 1C). These results suggested that entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ was dependent on depletion of Ca2+ stores regardless of the mechanism of depletion.

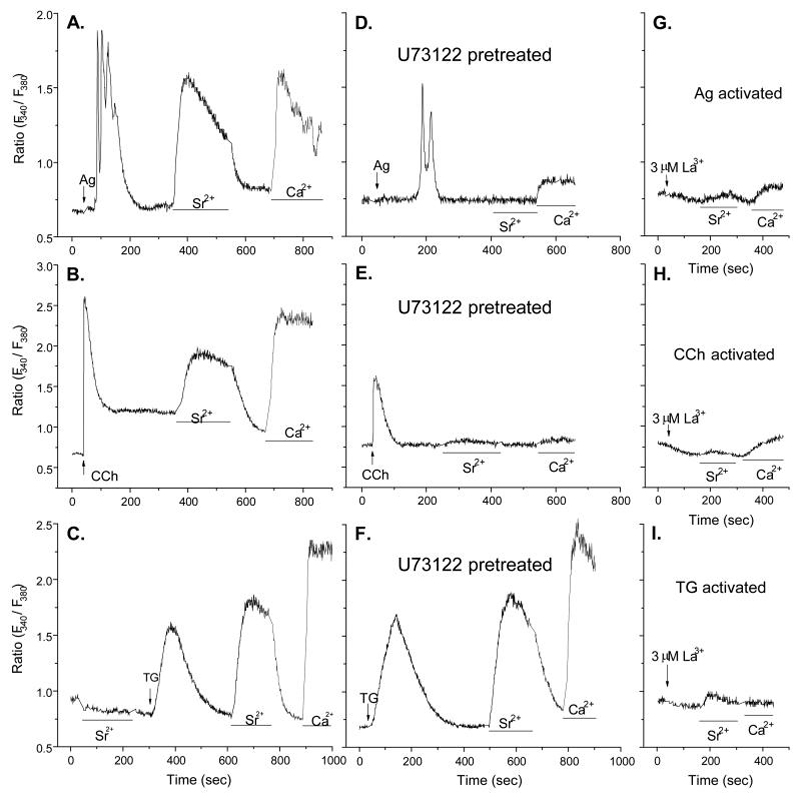

Figure 1.

Entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ is dependent on store depletion and inhibited by La3+. Changes in levels of cytosolic Ca2+ and Sr2+ were determined in Fura2-loaded RBL-2H3(m1) cells as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were first exposed to Ca2+-free medium and stimulated with 100 ng/ml antigen (Ag), 100 μM carbachol (CCh), or 1 μM thapsigargin (Tg). Cells were then exposed to medium containing Sr2+ (3 mM) or Ca2+ (1 mM) where indicated by the bars. In panels D, E, and F cells were exposed to the PLC inhibitor, U73122 (5 μM), 10 mins before addition of stimulants. In panels G to I, La3+ (3 μM) was added as indicated by the arrows. The data show traces for individual cells that are representative of a field of at least 20 cells. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

Another indication that entry of Sr2+, as well as Ca2+, can occur independently of PLC was that the PLC inhibitor, U73122, inhibited release of intracellular Ca2+ and reduced entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ when cells were stimulated by either Ag or carbachol (Fig. 1D and E) but it failed to suppress entry of these ions when Ca2+ stores were depleted with thapsigargin (Fig. 1F). However, the entry of both Sr2+ and Ca2+ in response to all three stimulants was blocked by La3+ (Fig. 1, panels G to I) at a concentration (3 μM) that is known to block CRAC activity in mast cells (7).

Identification of TRPC5 as a channel for store-dependent Sr2+ and Ca2+ entry

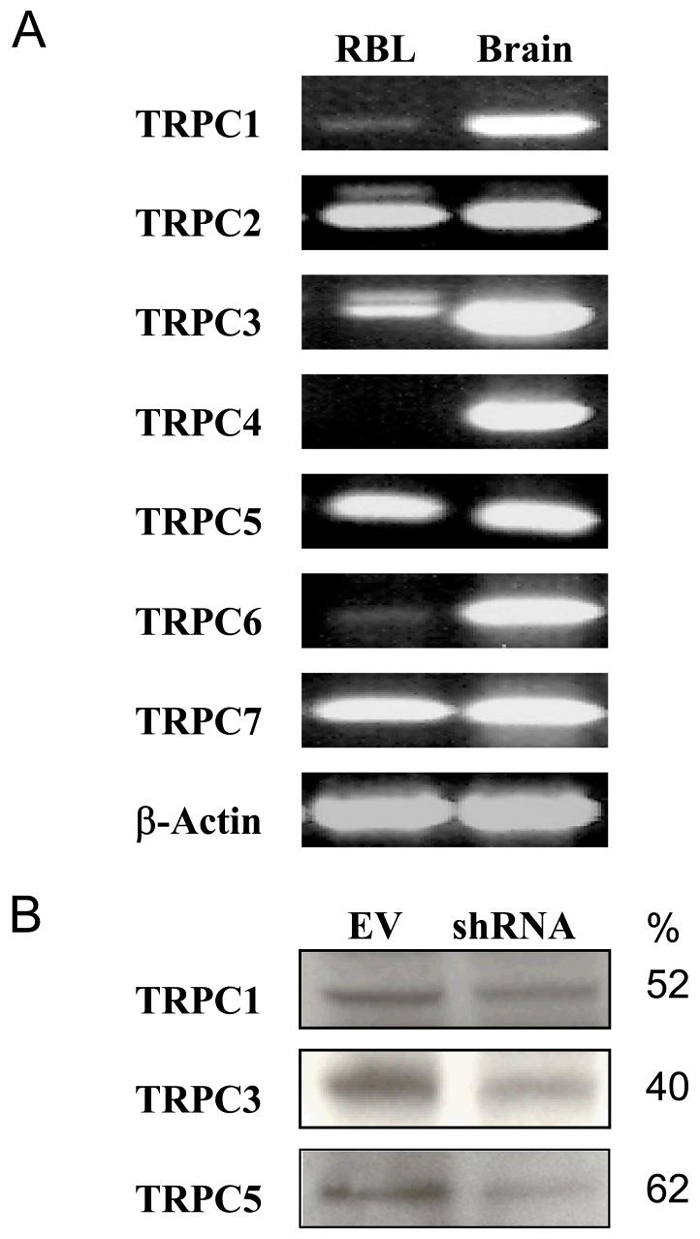

Messenger RNAs for several TRPCs were identified in RBL-2H3 cells by RT-PCR. These included TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC3, TRPC5, and TRPC7 (Fig. 2A). Of these, TRPC1, TRPC3, and TRPC5 could be detected at the protein level (Fig. 2B), whereas TRPC2, a pseudo-gene in some but not all species (56, 57), was not detectable in RBL-2H3 cells. Antibodies against TRPC7 lacked sufficient specificity for this purpose.

Figure 2.

Expression of TRPC family members in RBL-2H3 cells. (A) The expression of mRNA for seven members of the TRPC family and ß-actin in RBL-2H3 cells and whole rat brain was determined by RT-PCR and blotting as described in Materials and Methods. The blots are representative of three separate experiments. (B) TRPC proteins were also identified by immunoblotting in RBL-2H3 cells that had been transfected with empty vector (EV) or shRNA against the indicated TRPC to assess the effect of the shRNAs on TRPC expression. The numeric values indicate percent decrease in expression as determined by densitometry.

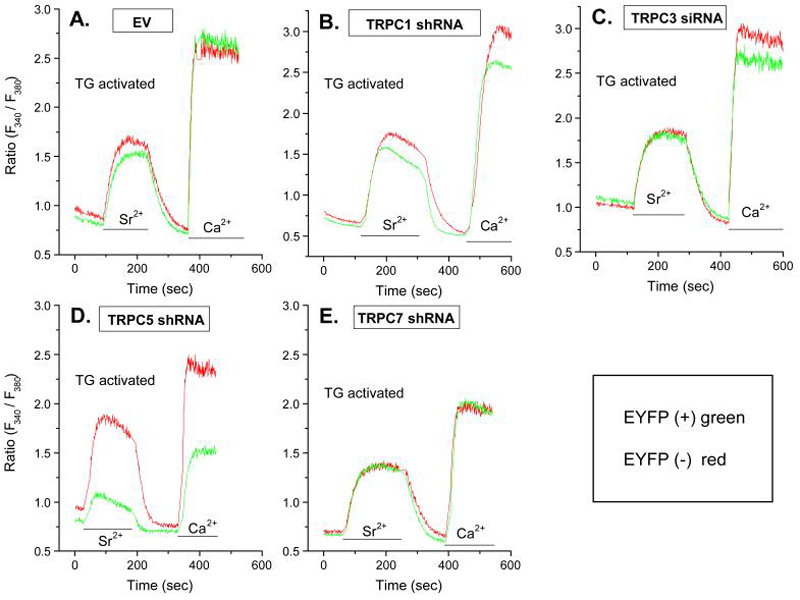

Knockdown of TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC5 (Fig. 2B), and TRPC7 with shRNAs indicated that only knockdown of TRPC5 substantially impaired entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ in thapsigargin-stimulated cells (Fig. 3, panels A to E). Entry of these cations was also unimpaired by prior transfection of cells with empty vector (Fig. 3A) or with shRNA against TRPC2 (data not shown). A small decrease in entry of cations was observed with knockdown of TRPC1 although the expression of this protein was decreased to a similar extent as TRPC5 (Fig. 2B). Other control experiments showed that shRNA against TRPC5 had no effect on expression of TRPC1 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Knock down of TRPCs by shRNAs shows that entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ is dependent on TRPC5. Cells were co-transfected with the indicated inhibitory RNA and YFP 48 h before measurement of Ca2+ and Sr2+ in Fura-2-loaded cells. Measurements were made in EYFP positive cells (green traces) and negative cells (red traces) to compare responses in transfected and non-transfected cells respectively. The traces show changes in ion levels 10 min after stimulation with 1 μM thapsigargin (Tg) in Ca2+-free medium when intracellular stores were depleted of Ca2+. Cells were then exposed to medium containing Sr2+ (3 mM) or Ca2+ (1 mM) where indicated by the bars. The data show traces for individual cells that are representative of a field of at least 10 cells for both YFP-positive and negative cells. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

Although entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ is dependent on store depletion in RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 1) and TRPC5 is reported to be activated by store-depletion (26), overexpressed TRPC5 can be activated in a PLC/diacylglycerol-dependent manner (58). However, we found that the diacylglycerol cell-permeant analog, 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol, or the use of the lipase inhibitor RHC80267 to increase diacylglycerol levels (30), failed to stimulate activate entry of Ca2+ or Sr2+ (data not shown). Together, these results suggested that of the TRPC family members, TRPC5 is a likely component of a SOCE channel in RBL-2H3 cells although a minor role for TRPC1 cannot be excluded.

Endogenous STIM1 and Orai1 also regulate store-operated Sr2+ and Ca2+ entry

STIM1, the sensor of free Ca2+ in calcium stores in the endoplasmic reticulum, was originally believed to regulate SOCE through its interaction with Orai1 to activate CRAC (32). Recent studies now suggest that STIM1 can also interact with TRPCs individually or in combination with Orai1. For example, transfection of cells with exogenously tagged proteins indicated that STIM1 can interact with TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC5 to regulate their activities (46). STIM1 also colocalizes with both TRPC1 and Orai1 and thus regulates SOCE (44). Interestingly, TRPC3 and TRPC6, which normally operate as receptor-activated and store-independent channels, appear to operate in a store-dependent manner when co-expressed with Orai1 (45).

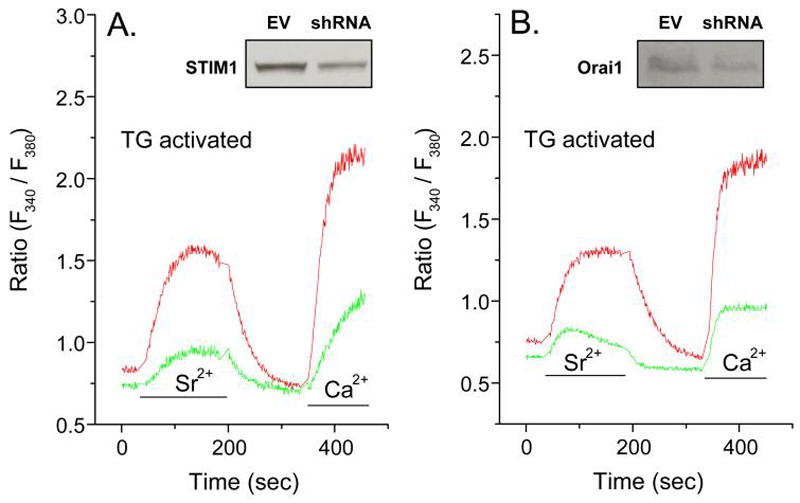

We found that endogenous STIM1 and Orai1 were essential for TRPC5 function because knock down or either STIM1 or Orai1 by use of shRNAs significantly suppressed thapsigargin-induced Sr2+ as well as Ca2+ entry (Fig. 4A and B). Therefore, both TRPC5 and Orai1 are required for Sr2+ and Ca2+ entry. Presumably, STIM1 serves as an essential sensor for the state of depletion of calcium stores.

Figure 4.

Knock down of STIM1 and Orai1 also suppress entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ in thapsigargin-stimulated cells. Cells were co-transfected with the indicated shRNA and EYFP 48 h before measurement of Ca2+ and Sr2+ in Fura2-loaded cells. Measurements were made in EYFP positive cells (green traces) and negative cells (red traces) to compare responses in transfected and non-transfected cells respectively. The traces show changes in ion levels 10 min after stimulation with 1 μM thapsigargin (Tg) in Ca2+-free medium when intracellular stores were depleted of Ca2+. Cells were then exposed to medium containing Sr2+ (3 mM) or Ca2+ (1 mM) where indicated by the bars. The data show traces for individual cells that are representative of a field of at least 10 cells for both EYFP-positive and negative cells. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments. The insets show levels of STIM1 or Orai1, as determined by immunoblotting, in cells transfected with empty vector (EV) or shRNA against STIM1 or Orai1.

Effects of overexpressed Orai1 or TRPC5 with STIM1 on store-operated Sr2+ and Ca2+ entry

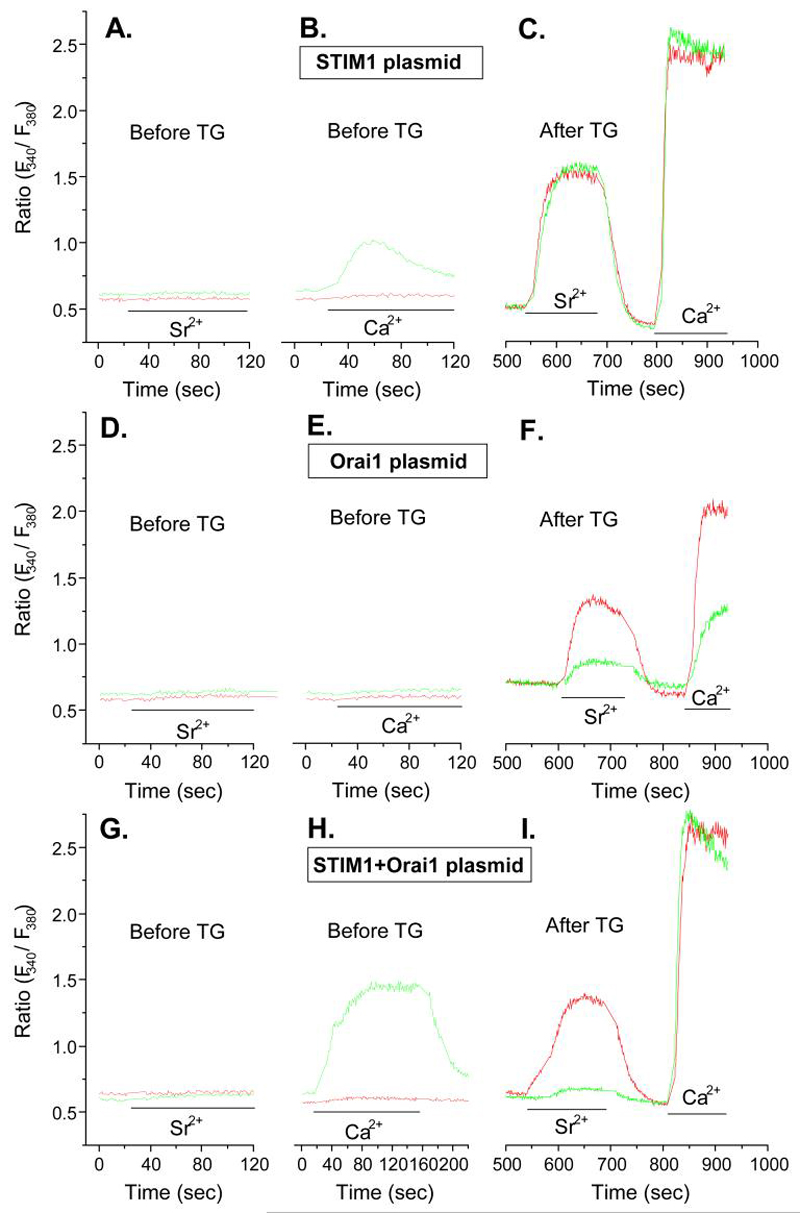

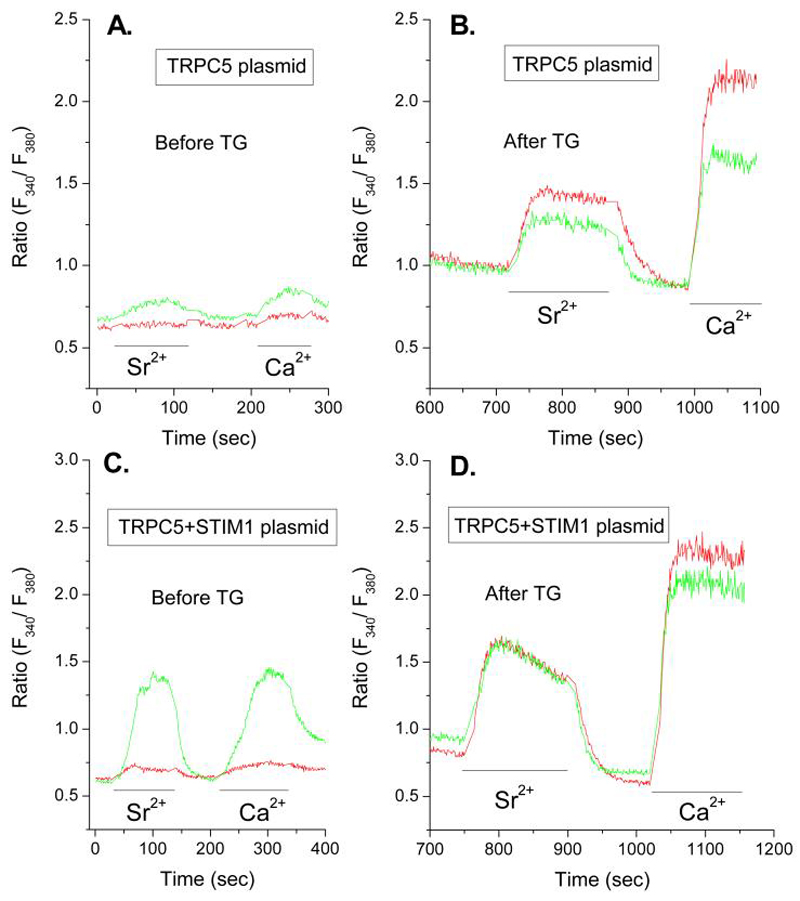

To verify that Orai1, TRPC5, and STIM1 acted in combination to facilitate entry of either Ca2+ or Sr2+, we examined the effects of overexpression of these molecules in RBL-2H3 cells. Of note, overexpression of STIM1 along with Orai1 or TRPC5 permitted constitutive entry of these cations in non-stimulated cells. This is illustrated in Figures 5 and 6 which show typical traces for Fura2-loaded cells before and after depletion of intracellular Ca2+-stores with thapsigargin.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of STIM1 and Orai1 reveal different features for the entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+. Cells were co-transfected with EYFP and STIM1, Orai1, or STIM1 and Orai1 in combination as indicated 48 h before measurement of Ca2+ and Sr2+ in Fura-2-loaded cells. Measurements were made in EYFP-positive cells (green traces) and negative cells (red traces) to compare responses in transfected and non-transfected cells respectively. The traces show changes in intracellular ion levels before and after addition of Sr2+ (3 mM) or Ca2+ (1 mM) as indicated by the bars. Two sets of panels (Panels A, D, and G and Panels B, E, and H) show traces before addition of thapsigargin. Panels C, F, and I show traces 10 min after depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with 1 μM thapsigargin (Tg). The data show traces for individual cells that are representative of a field of at least 10 cells for both EYFP-positive and negative cells. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of STIM1 and TRPC5 reveal that TRPC5 conveys both Sr2+ and Ca2+. Cells were co-transfected with EYFP and TRPC5 alone or combination with STIM1 as indicated 48 h before measurement of Ca2+ and Sr2+ in Fura-2-loaded cells. Measurements were made in EYFP-positive cells (green traces) and negative cells (red traces) to compare responses in transfected and non-transfected cells respectively. The traces show changes in intracellular ion levels in Ca2+ -free medium without stimulation. Cells were exposed to medium containing Sr2+ (3 mM) or Ca2+ (1 mM) as indicated by the bars. Panels A and B show traces before stimulation. Panels C and D show traces 10 min after addition of 1 μM thapsigargin (Tg) when intracellular stores were depleted of Ca2+ in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Cells were then exposed to medium containing Sr2+ (3 mM) or Ca2+ (1 mM) where indicated by the bars. The data show traces for individual cells that are representative of a field of at least 10 cells for both EYFP-positive and negative cells. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

Overexpression of STIM1 by itself resulted in little or no constitutive entry of Sr2+ but it did result in modest influx of Ca2+ in the absence of stimulation (Fig. 5A and B). Otherwise, the overexpression of STIM1 did not affect the stimulated entry of either Sr2+ or Ca2+ after depletion of Ca2+-stores with thapsigargin (Fig. 5C). In contrast to STIM1, overexpression of Orai1 did not permit constitutive entry of Sr2+ or Ca2+ and suppressed entry of these ions in thapsigargin-stimulated cells (Fig. 5, panels D to F). However, co-expression of STIM1 with Orai1 permitted constitutive entry Ca2+, but not Sr2+ (Fig. 5G and H), and fully restored entry of Ca2+ after depletion of Ca2+-stores with thapsigargin while Sr2+ entry remained blocked (Fig. 5I). The suppression of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+-entry following overexpression of Orai1 and restoration of Ca2+-entry on co-expression with STIM1 has been noted by other investigators with different cell lines (41-43). Our results show, in addition, that the co-expression of STIM1 and Orai1 allows substantial constitutive entry of Ca2+ (i.e. Fig. 5H) but excludes entry of Sr2+ under all conditions (i.e., Fig. 5I).

In contrast to Orai1, overexpression of TRPC5 resulted in some constitutive entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ (Fig. 6A) and suppressed entry of both ions in thapsigargin-treated cells but to a lesser extent than Orai1 (Fig. 6B). In combination with STIM1, the constitutive entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ was substantially enhanced (Fig. 6C) and entry of both ions was fully restored in thapsigargin-treated cells (Fig. 6D).

The above data (Figs. 5 and 6) demonstrate that transient coexpression of Orai1 and STIM1 allows influx of only Ca2+ whereas coexpression of TRPC5 and STIM1 allows influx of Sr2+ as well as Ca2+. The studies with shRNAs (Figs. 3 and 4) had indicated that endogenous TRPC5 as well as STIM1 and Orai1 are required for optimal entry Sr2+ and Ca2+ following depletion of Ca2+-stores with thapsigargin to suggest that all three proteins interact with each other. The suppression of Sr2+ or Ca2+ influx by overexpression of Orai1 (Fig. 5D) or TRPC5 (Fig. 6B) could also imply that channel competency requires stoichiometric interaction of Orai1 with STIM1 or TRPC5. One possibility is that overexpressed Orai1 may preferentially oligomerize with itself (59, 60) rather than with TRPC5, and vice versa, with loss of conductance of Sr2+ and Ca2+ through a TRPC5-Orai1 complex. Another caveat is that overexpression may lead to protein interactions that do not normally occur. The constitutive entry of cations noted here with over expressed STIM1 in combination with Orai1 or TRPC5 might indicate such interactions. Nevertheless, the data in total clearly indicate that the interaction of these proteins can result in different channel properties.

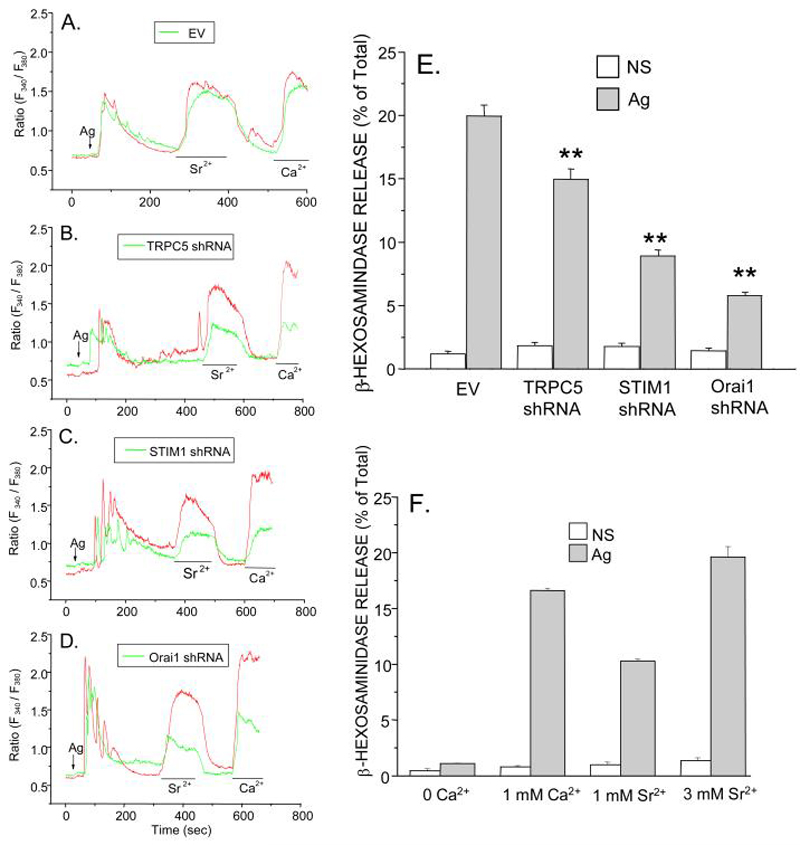

TRPC5, STIM1, and Orai1 are required for cation influx and degranulation in Ag-stimulated cells

As with thapsigargin-stimulated cells, influx of Sr2+ and Ca2+ was significantly suppressed when cells were stimulated with Ag following knock down of TRPC5, STIM1, or Orai1 (Fig. 7, panels B to D) as compared to empty vector transfected cells (Fig. 7A). Ag-stimulated release of intracellular Ca2+ was unaffected. Knock down of each of these proteins also significantly impaired degranulation in Ag-stimulated cells (Fig. 7E). As in previous studies (13), Sr2+ could substitute for Ca2+ in promoting degranulation, partially so at 1 mM and fully so at 3 mM Sr2+ (Fig. 7F). If TRPC5 is the exclusive carrier of Sr2+ as the preceding data suggests, TRPC5 would appear to be essential for degranulation as well as SOCE.

Figure 7.

TRPC5, STIM1, and Orai1 are essential for entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ as well as degranulation in Ag-stimulated cells. A-D As in previous figures, changes in intracellular Ca2+ and Sr2+ were determined in Fura-2-loaded cells (in Ca2+-free medium) following addition of Ag, 1mM Ca2+, or 3 mM Sr2+ where indicated. Cells were previously transfected with empty vector (EV) or shRNAs against TRPC5, STIM1, or Orai1 along with EYFP to allow selection of transfected (green trace) and non-transfected (red trace) cells for imaging. E Degranulation was determined in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+ by measurement of the release of the granule marker, ß-hexosaminidase, into the medium in non-stimulated (NS) and Ag-stimulated cultures 15 min after addition of Ag. Cells had been transfected with empty vector (EV) or the indicated shRNAs. Asterisks indicate significant decrease in degranulation, ** p<0.01. F The extent of degranulation in normal RBL-2H3 cells in the absence or presence of 1 mM Ca2+, 1 mM Sr2+ or 3 mM Sr2+ is also shown. The transfection efficiences were 70-80% for the experiments shown in Panels D and E, Values are the mean ± SEM of three cultures. Similar results were obtained in two additional experiments.

Concluding comments

The original studies of Ca2+-dependent exocytosis (11, 12) and our early studies (2, 13) showed that Sr2+ and other divalent cations are taken-up by stimulated mast cells and can replace Ca2+ in promoting degranulation. These observations preclude CRAC as the sole mechanism for conveyance of Ca2+ into the cell because of the high Ca2+ selectivity of CRAC (61, 62) and the diminution of CRAC activity on replacement of Ca2+ with other divalent cations (9, 10). It has been suggested that the channel properties of Orai1 may be modified by other proteins because the properties of CRAC, especially its low conductivity and specificity for Ca2+, are not entirely recapitulated by overexpressed Orai1 and STIM1 (32). We suggest that TRPC5 may be one such protein that allows entry of Sr2+ and Ca2+ into RBL-2H3 cells. Although influx of these two ions are readily distinguishable (Figs. 5 and 6), entry of both are dependent on TRPC5 (Fig. 3D), STIM1 (Fig. 4A), and Orai1 (Fig. 4B). A plausible scenario is that entry is dependent on formation of a ternary complex of STIM1-Orai1-TRPC5 in which STIM1 acts as a Ca2+ sensor and Sr2+-permeable TRPC5 in conjunction with Orai1 enhances entry of Ca2+. This scenario is analogous to the proposals based on a ternary complex of STIM1-Orai1-TRPC1 (44), the interaction of Orai1 with TRPC3 or TRPC6 (45), and the interaction of STIM1 with various TRPCs (46). These interactions have been demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation of expressed tagged proteins (44-46) or, in one case, endogenous TRPC1 with STIM1 (44). Our attempts to demonstrate similar associations for endogenous proteins in RBL-2H3 cells were unsuccessful because of the limitations of the available antibodies. Although TRPC5 as well as Orai1 and STIM1 are essential for influx of Ca2+ and degranulation in RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 7), we cannot exclude a minor contribution of TRPC1 although this protein is thought not to be an endogenous component of CRAC in RBL-2H3 cells (44). Also, given the phenotypic diversity of mast cells (63, 64) and the possible variations in the combinations of Orai and TRPC family members, it is possible that such combinations may vary among different sub-types of mast cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sachini Bandara (Laboratory of Allergic Diseases, NIAID) for skillful assistance in the performance of RT-PCR.

This work was supported by the Intramural Programs of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Allergic and Inflammatory Diseases.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CRAC

calcium release-activated Ca2+ current

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- PL

phospholipase

- siRNA

small inhibitory RNA

- sh

short hairpin

- SOCE

store-operated Ca2+ entry

- TRPC

transient receptor potential canonical

References

- 1.Ozawa K, Szallasi Z, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Mischak H, Mushinski JF, Beaven MA. Ca2+-Dependent and Ca2+-independent isozymes of protein kinase C mediate exocytosis in antigen-stimulated rat basophilic RBL-2H3 cells: Reconstitution of secretory responses with Ca2+ and purified isozymes in washed permeabilized cells. J.Biol.Chem. 1993;268:1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali H, Maeyama K, Sagi-Eisenberg R, Beaven MA. Antigen and thapsigargin promote influx of Ca2+ in rat basophilic RBL-2H3 cells by ostensibly similar mechanisms that allow filling of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive and mitochondrial Ca2+ stores. Biochem.J. 1994;304:431–440. doi: 10.1042/bj3040431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaven MA, Rogers J, Moore JP, Hesketh TR, Smith GA, Metcalfe JC. The mechanism of the calcium signal and correlation with histamine release in 2H3 cells. J.Biol.Chem. 1984;259:7129–7136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millard PJ, Ryan TA, Webb WW, Fewtrell C. Immunoglobulin E receptor cross-linking induces oscillations in intracellular free ionized calcium in individual tumor mast cells. J.Biol.Chem. 1989;264:19730–19739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berridge MJ. Capacitative calcium entry. Biochem.J. 1995;312:1–11. doi: 10.1042/bj3120001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Putney JW., Jr. Capacitative calcium entry revisited. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:611–624. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90016-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoth M, Penner R. Calcium release-activated calcium current in rat mast cells. J.Physiol. (Lond) 1993;465:359–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parekh AB, Penner R. Regulation of store-operated calcium currents in mast cells. Soc.Gen.Physiol. Ser. 1996;51:231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweifach A, Lewis RS. Calcium-dependent potentiation of store-operated calcium channels in T lymphocytes. J.Gen.Physiol. 1996;107:597–610. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christian EP, Spence KT, Togo JA, Dargis PG, Patel J. Calcium-dependent enhancement of depletion-activated calcium current in Jurkat T lymphocytes. J.Membr.Biol. 1996;150:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s002329900030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foreman JC, Mongar JL. The role of the alkaline earth ions in anaphylactic histamine secretion. J.Physiol. (Lond) 1972;224:753–769. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foreman JC, Hallett MB, Mongar JL. Movement of strontium ions into mast cells and its relationship to the secretory response. J.Physiol. (Lond) 1977;271:233–251. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hide M, Beaven MA. Calcium influx in a rat mast cell (RBL-2H3) line: Use of multivalent metal ions to define its characteristics and role in exocytosis. J.Biol.Chem. 1991;266:15221–15229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philipp S, Cavalie A, Freichel M, Wissenbach U, Zimmer S, Trost C, Marquart A, Murakami M, Flockerzi V. A mammalian capacitative calcium entry channel homologous to Drosophila TRP and TRPL. EMBO J. 1996;15:6166–6171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zitt C, Zobel A, Obukhov AG, Harteneck C, Kalkbrenner F, Luckhoff A, Schultz G. Cloning and functional expression of a human Ca2+-permeable cation channel activated by calcium store depletion. Neuron. 1996;16:1189–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freichel M, Suh SH, Pfeifer A, Schweig U, Trost C, Weissgerber P, Biel M, Philipp S, Freise D, Droogmans G, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Nilius B. Lack of an endothelial store-operated Ca2+ current impairs agonist-dependent vasorelaxation in TRP4-/- mice. Nat.Cell Biol. 2001;3:121–127. doi: 10.1038/35055019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warnat J, Philipp S, Zimmer S, Flockerzi V, Cavalie A. Phenotype of a recombinant store-operated channel: highly selective permeation of Ca2+ J.Physiol. 1999;518(Pt 3):631–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0631p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Wang W, Singh BB, Lockwich T, Jadlowiec J, O'Connell B, Wellner R, Zhu MX, Ambudkar IS. Trp1, a candidate protein for the store-operated Ca2+ influx mechanism in salivary gland cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;275:3403–3411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freichel M, Vennekens R, Olausson J, Stolz S, Philipp SE, Weissgerber P, Flockerzi V. Functional role of TRPC proteins in native systems: implications from knockout and knock-down studies. J.Physiol. 2005;567:59–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomita Y, Kaneko S, Funayama M, Kondo H, Satoh M, Akaike A. Intracellular Ca2+ store-operated influx of Ca2+ through TRP-R, a rat homolog of TRP, expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci.Lett. 1998;248:195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, Babnigg G, Villereal ML. Functional significance of human trp1 and trp3 in store-operated Ca2+ entry in HEK-293 cells. Am.J.Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C526–C536. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brough GH, Wu S, Cioffi D, Moore TM, Li M, Dean N, Stevens T. Contribution of endogenously expressed Trp1 to a Ca2+-selective, store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway. FASEB J. 2001;15:1727–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweeney M, Yu Y, Platoshyn O, Zhang S, McDaniel SS, Yuan JX. Inhibition of endogenous TRP1 decreases capacitative Ca2+ entry and attenuates pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am.J.Physiol. Lung Cell Mol.Physiol. 2002;283:L144–L155. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00412.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H, Mergler S, Sun X, Wang Z, Lu L, Bonanno JA, Pleyer U, Reinach PS. TRPC4 knockdown suppresses epidermal growth factor-induced store-operated channel activation and growth in human corneal epithelial cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2005;280:32230–32237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504553200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brueggemann LI, Markun DR, Henderson KK, Cribbs LL, Byron KL. Pharmacological and electrophysiological characterization of store-operated currents and capacitative Ca2+ entry in vascular smooth muscle cells. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 2006;317:488–499. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng F, Xu SZ, Jackson PK, McHugh D, Kumar B, Fountain SJ, Beech DJ. Human TRPC5 channel activated by a multiplicity of signals in a single cell. J.Physiol. 2004;559:739–750. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plant TD, Schaefer M. TRPC4 and TRPC5: receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channels. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaefer M, Plant TD, Obukhov AG, Hofmann T, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Receptor-mediated regulation of the nonselective cation channels TRPC4 and TRPC5. J.Biol.Chem. 2000;275:17517–17526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.23.17517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birnbaumer L, Yildirim E, Abramowitz J. A comparison of the genes coding for canonical TRP channels and their M, V and P relatives. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:419–432. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature. 1999;397:259–263. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okada T, Inoue R, Yamazaki K, Maeda A, Kurosaki T, Yamakuni T, Tanaka I, Shimizu S, Ikenaka K, Imoto K, Mori Y. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel mouse transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP7. Ca2+-permeable cation channel that is constitutively activated and enhanced by stimulation of G protein-coupled receptor. J.Biol.Chem. 1999;274:27359–27370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Jones BF, Mercer JC, Trebak M, Vazquez G, Putney JW., Jr. Emerging perspectives in store-operated Ca2+ entry: roles of Orai, Stim and TRP. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2006;1763:1147–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J.Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr., Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr.Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spassova MA, Soboloff J, He LP, Xu W, Dziadek MA, Gill DL. STIM1 has a plasma membrane role in the activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2006;103:4040–4045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ames JB, Ikura M. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of STIM1 via the EF-SAM region: An initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J.Biol.Chem. 2006;281:35855–35862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. CRACM1 Is a Plasma Membrane Protein Essential for Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry. Science. 2006;312:1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feske S, Prakriya M, Rao A, Lewis RS. A severe defect in CRAC Ca2+ channel activation and altered K+ channel gating in T cells from immunodeficient patients. J.Exp.Med. 2005;202:651–662. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercer JC, Dehaven WI, Smyth JT, Wedel B, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J.Biol.Chem. 2006;281:24979–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604589200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peinelt C, Vig M, Koomoa DL, Beck A, Nadler MJ, Koblan-Huberson M, Lis A, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1) Nat.Cell Biol. 2006;8:771–773. doi: 10.1038/ncb1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soboloff J, Spassova MA, Tang XD, Hewavitharana T, Xu W, Gill DL. Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store-operated calcium channel function. J.Biol.Chem. 2006;281:20661–20665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ong HL, Cheng KT, Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Paria BC, Soboloff J, Pani B, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Singh BB, Gill D, Ambudkar IS. Dynamic assembly of TRPC1-STIM1-Orai1 ternary complex is involved in store-operated calcium influx. Evidence for similarities in store-operated and calcium release-activated calcium channel components. J.Biol.Chem. 2007;282:9105–9116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608942200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao Y, Erxleben C, Yildirim E, Abramowitz J, Armstrong DL, Birnbaumer L. Orai proteins interact with TRPC channels and confer responsiveness to store depletion. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2007;104:4682–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Huang GN, Worley PF, Muallem S. STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels to determine their function as store-operated channels. Nat.Cell Biol. 2007;9:636–645. doi: 10.1038/ncb1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwaki S, Tkaczyk C, Satterthwaite AB, Halcomb K, Beaven MA, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Btk plays a crucial role in the amplification of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation by Kit. J.Biol.Chem. 2005;280:40261–40270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Babich LG, Ku CY, Young HW, Huang H, Blackburn MR, Sanborn BM. Expression of capacitative calcium TrpC proteins in rat myometrium during pregnancy. Biol.Reprod. 2004;70:919–924. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones S, V, Choi OH, Beaven MA. Carbachol induces secretion in a mast cell line (RBL-2H3) transfected with the m1 muscarinic receptor gene. FEBS Lett. 1991;289:47–50. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80905-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi OH, Lee JH, Kassessinoff T, Cunha-Melo JR, Jones S, V, Beaven MA. Carbachol and antigen mobilize calcium by similar mechanisms in a transfected mast cell line (RBL-2H3 cells) that expresses m1 muscarinic receptors. J.Immunol. 1993;151:5586–5595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andrade MV, Hiragun T, Beaven MA. Dexamethasone suppresses antigen-induced activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and downstream responses in mast cells. J.Immunol. 2004;172:7254–7262. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venkatachalam K, Ma HT, Ford DL, Gill DL. Expression of functional receptor-coupled TRPC3 channels in DT40 triple receptor InsP3 knockout cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:33980–33985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cissel DS, Fraundorfer PF, Beaven MA. Thapsigargin-induced secretion is dependent on activation of a cholera toxin-sensitive and a phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-regulated phospholipase D in a mast cell line. J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 1998;285:110–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park DJ, Min HK, Rhee SG. IgE-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ1 in rat basophilic leukemia cells. J.Biol.Chem. 1991;266:24237–24240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Popova JS, Rasenick MM. Muscarinic receptor activation promotes the membrane association of tubulin for the regulation of Gq-mediated phospholipase C1β1 signaling. J.Neurosci. 2000;20:2774–2782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02774.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zufall F. The TRPC2 ion channel and pheromone sensing in the accessory olfactory system. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch.Pharmacol. 2005;371:245–250. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zufall F, Ukhanov K, Lucas P, Leinders-Zufall T. Neurobiology of TRPC2: from gene to behavior. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:61–71. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Venkatachalam K, Zheng F, Gill DL. Regulation of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channel function by diacylglycerol and protein kinase C. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:29031–29040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeromin AV, Zhang SL, Jiang W, Yu Y, Safrina O, Cahalan MD. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vig M, Beck A, Billingsley JM, Lis A, Parvez S, Peinelt C, Koomoa DL, Soboloff J, Gill DL, Fleig A, Kinet JP, Penner R. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr.Biol. 2006;16:2073–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Premack BA, McDonald TV, Gardner P. Activation of Ca2+ current in Jurkat T cells following the depletion of Ca2+ stores by microsomal Ca2+-ATPase inhibitors. J.Immunol. 1994;152:5226–5240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zweifach A, Lewis RS. Mitogen-regulated Ca2+ current of T lymphocytes is activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1993;90:6295–6299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Forsythe P, Ennis M. Clinical consequences of mast cell heterogeniety. Inflam.Res. 2000;49:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s000110050574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Welle M. Development, significance, and heterogeneity of mast cells with particular regard to the mast cell-specific proteases chymase and tryptase. J.Leukoc.Biol. 1997;61:233–245. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]