Abstract

BACKGROUND

Prior authorization is a popular, but understudied strategy for reducing medication costs. We evaluated the impact of a controversial prior authorization policy in Michigan Medicaid on antidepressant use and health outcomes among dual Medicaid and Medicare enrollees with a Social Security Disability Insurance designation of disability.

METHODS

We linked Medicaid and Medicare (2000–2003) claims for dual enrollees in Michigan and a comparison state, Indiana. Using interrupted time series and longitudinal data analysis, we estimated the impact of the policy on antidepressant medication use, treatment initiation, disruptions in therapy and adverse health events among continuously enrolled (MI=28,798, IN=21,769) and newly treated (MI=3,671, IN=2,400) patients.

RESULTS

In Michigan, the proportion of patients initiating on non-preferred agents declined from 53% pre policy to 20% post policy. The policy was associated with a small sustained decrease in therapy initiation overall (9 per 10,000; p<0.05). We also observed a short-term increase in switching among established users of non-preferred agents overall (RR: 2.88(1.87, 4.42)) and among those with depression (RR: 2.04(1.22, 3.42)). However, we found no evidence of increased disruptions in treatment or adverse events (i.e., hospitalization, emergency room use) among newly treated patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Prior authorization was associated with increased use of preferred agents with no evidence of disruptions in therapy or adverse health events among new users. However, unintended impacts on treatment initiation and switching among patients already established on the therapy were also observed, lending support to the state’s previous decision to discontinue prior approval for antidepressants in 2003.

Psychotropic medication spending among dual enrollees has contributed to the rising popularity of prior authorization (PA) among Medicaid and Medicare Part D plans.(1,2) Under PA, pre-approval is required for reimbursement of prescriptions for particular drugs or drug categories. Despite their widespread use, few studies have examined the impact of PA policies on rates of medication use and health outcomes among vulnerable Medicaid and Medicare enrollees.(3–5) In a recent study of Medicaid enrollees with schizophrenia, we observed increased gaps in treatment associated with prior authorization requirements for atypical antipsychotic medications.(5) Non-elderly disabled dual enrollees may be especially vulnerable to PA-related disruptions in therapy due to a higher reliance on psychotropic medications, high prevalence of complex co-morbidities, and lower socioeconomic status, which may inhibit their ability to navigate changes in coverage.(2,4) The heightened vulnerability of dual enrollees has sparked concerns about their random assignment to Medicare Part D plans, many of which require PA for mental health drugs.(6)

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the impact of the Michigan PA for non-preferred antidepressants among non-elderly disabled dual enrollees. In March 2002, the Michigan Medicaid program began requiring prior approval for new prescriptions of non-preferred antidepressants, including commonly used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [citalopram (Celexa), fluvoxamine (Luvox), brand fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem), and sertraline (Zoloft)] and venlafaxine (serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SNRI). Preferred agents included generic fluoxetine (newly off patent) and paroxetine (Paxil, Paxil CR).(7)

Federal rules required the state to respond to clinician requests for prior authorization within 24 hours and to provide a 72-hour emergency drug supply while the request was being processed. In addition, Michigan Medicaid grandfathered or excluded from the policy patients already established on non-preferred medications. Following policy implementation, patient advocacy groups reported barriers to medication access resulting from the Michigan antidepressant PA.(7) In late June of 2003, after clinical review of the PDL, the Medicaid Director announced the removal of prior approval for antidepressants and other mental health medications, stating that “Making more of these critical drugs available without the need for prior-authorization helps to avoid possible setbacks in care due to changes in drug treatment therapy.”(8) To date, an external evaluation of this policy has not been published.

Based on our previous study,(5) we hypothesized that the policy would reduce the use of non-preferred SSRI/SNRI agents among dual enrollees. However, we also hypothesized that problems in the implementation of the PA policy may have resulted in short-term disruptions in treatment, including unintended switching of antidepressants among established users, and lower rates of initiation of antidepressant treatment.

Among newly treated dual enrollees, the population targeted by the policy, we investigated the impact of the policy on patterns of medication use (i.e., switching/augmentation, discontinuation, persistence) and use of non-drug health services (i.e., hospitalization, emergency room admission). We hypothesized that the policy may result in treatment disruptions that may reflect differences in treatment effectiveness, confusion about the policy and other factors. Finally, we hypothesized that undesired changes in medication use (i.e., early discontinuation) may have resulted in adverse health events (e.g., hospitalization, emergency room use) within this vulnerable subset of Medicaid patients.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Population

We linked Medicaid and Medicare enrollment and claims data from 2000 through 2003 to identify two distinct cohorts in Michigan (MI) and Indiana (IN). First, we identified patients who were continuously enrolled in Michigan or Indiana Medicaid and concurrently enrolled in Medicare for all four years. We included only patients who were between the ages of 18 and 64 and who had a Social Security Disability Insurance designation of permanent disability. We excluded patients with any Medicare or Medicaid managed care enrollment. Within the continuously enrolled cohort, we identified analytic subgroups of potential initiators and established users of antidepressant therapy (see outcome measures below).

We defined a second cohort of non-elderly fee-for-service enrollees between November 2000 and December 2002 who had an outpatient dispensing for an SSRI or SNRI with no evidence of a dispensing of any antidepressant agent during the previous six months.(9) Within this cohort of newly treated patients, we identified two sub-cohorts: (1) the pre-policy cohort, who initiated SSRI/SNRI therapy between November 2000 and August 2001; and (2) the post-policy cohort, who initiated therapy between March 2002 and December 2002. This allowed 10 months for accrual and a minimum of six months of medication follow up with no overlap between the six-month follow up period for the pre-policy cohort with the accrual period for the post-policy cohort. Newly treated patients were required to be continuously dually enrolled in Michigan or Indiana for 10 months before and one year after the initiation of SSRI/SNRI therapy. We further required that newly treated patients have fewer than 45 days in an institution (e.g., hospital) during the 90 days prior to initiation of therapy.

While we did not require a depression diagnosis for inclusion in either the continuously enrolled or newly treated cohorts, we conducted subgroup analyses for patients with evidence of depression, indicated by at least one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses of depression (ICD9: 296.2, 296.3, 298.0, 300.4, 309.1, 311). We also examined high risk subgroups of patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (295) and bipolar disorder (296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.7, 296.89, and 301.11).

Outcome Measures

Rates of Medication Use

To examine overall trends in medication use within the continuously enrolled population, we used an interrupted time series with comparison series design to examine changes in trends in the proportion of patients using all, SSRI/SNRIs (preferred and non-preferred), and other antidepressants. Preferred and non-preferred categories were determined by the state PA rules except for fluoxetine. Because of the introduction of generic fluoxetine to the market prior to policy implementation, we included both generic and brand fluoxetine into the preferred medication category. This allowed us to separate shifts in market share due to generic entry from the effect of the policy. For each generic entity, we then used days supply information from pharmacy claims to create patient-level measures of change in medication utilization among defined sub-populations (i.e., potential initiators, established users, newly treated patients).

Rates of Therapy Initiation

From the continuously enrolled cohort, we identified a rolling sub-cohort of potential antidepressant initiators, defined as having no antidepressant use in the previous six months and fewer than 45 institutional days during the previous three months. This denominator was then used to calculate the proportion of patients in each month who initiated any, SSRI/SNRI or other antidepressant therapy. This proportion was the primary outcome measure in a time series model predicting changes in the level and trend in rates of initiation.

Rates of Switching among Established Users

Similarly, we identified a rolling cohort of established SSRI/SNRI users, defined as having had at least two dispensings of a single SSRI or SNRI therapy during the previous six months. We calculated the monthly proportion of these individuals who received a second antidepressant agent and no subsequent dispensing of the first agent in the following six-month period. This indicator was the primary outcome of interest in a patient-level analysis examining changes in the likelihood of unintended switching among those previously established on antidepressant therapies. Given the rolling cohort design employed for this outcome, we used a different definition of the pre and post policy period to allow for an examination of switching during the period of policy implementation (pre-policy: March 2001–January 2002; policy implementation: February–April 2002; post-policy: May 2002–April 2003)

Patterns of Antidepressant Use among Newly Treated Patients

Among newly treated patients, we also examined three patient-level medication use outcomes: switching/augmentation, discontinuation, and persistence with therapy. We defined switching/augmentation as dispensing of a second antidepressant agent during the six months following therapy initiation. This definition was broader than that used for the cohort of current users as it allowed for augmentation (i.e., addition of a second agent without discontinuation of the first agent). We treat both switching and augmentation as indicators of lack of response to the initial therapeutic regimen. Discontinuation was defined as a gap in available therapy of at least 30 days during the first six months following initiation of treatment. Time until switching/augmentation and discontinuation were the primary outcomes for patient-level survival analysis.

We defined persistence as having medication available for at least four out of six months following initiation of therapy.(10) This measure was included as a dichotomous outcome for patient-level analyses exploring the impact of the policy on continuity of treatment. We censored patients with no evidence of use for 30 days or more.

Hospitalization and Emergency Department Use among Newly Treated Patients

We assessed potential adverse clinical effects of the policy by examining changes in the risk of hospitalization and emergency room utilization, comparing patients who initiated therapy before or after the policy implementation in the study and comparison state. Hospital events were counted if they included at least one overnight stay. Emergency room visit counts excluded those that resulted in a hospital episode. We examined all hospital and emergency room events.

Covariates

From the Medicaid and Medicare enrollment files, we identified patient age (≤34; 35–54; and 55+), race (black, white, other), and gender, which may have influenced both the timing and use of antidepressant therapy.(11,12) We approximated level of comorbidity using a count of the total number of non-antidepressant medications used by each patient at baseline.(13)

Statistical Analysis

We estimated population-level changes in our medication utilization measures in Michigan and Indiana (i.e., level, trend) using interrupted time-series models,(14,15) including the proportion of enrollees using antidepressant medications per month and the proportion of patients initiating treatment in each month. Model fit was assessed using a Durbin Watson statistic and we tested for autocorrelation and nonlinearity of the outcomes of interest. For parsimony, non-significant terms (p>0.05) were excluded from the final time series models.(16)

Patient-level effects of the policy were assessed using generalized estimating equations (GEE)(17) and survival analysis.(18) First, we used a segmented GEE to estimate the likelihood of switching from current SSRI or SNRI monotherapy overall, and by preferred and non-preferred drug status. The model included three time periods: one year pre-policy (March 2001–January 2002), a three-month policy implementation period (February 2002–April 2002); and one year post-policy (May 2002–April 2003). An interaction term between state (Michigan=1) and the post-policy time segments provided an indicator of short- and long-term policy impact.

These models also included age, race, gender, level of comorbidity, and the number of dispensings of antidepressant therapy in the previous six months to control for frequency of use. The robust sandwich estimator was utilized for the modeling of the correlated error structure.(16) We also conducted a subgroup analysis for patients with evidence of depression.

Among the newly treated cohort, we used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the hazard of switching/augmentation and discontinuation for patients who initiated therapy before (November 2000–August 2001) and after (March 2002–December 2002) the policy in each state. The models included age, gender, race and level of comorbidity. We also conducted analyses for patients with depression. We tested the proportional hazards assumption using the supremum test.(17) The models controlled for age, race, gender and comorbidity as described above.

To estimate the impact of the policy on persistence of treatment, we used generalized linear models to assess the impact of the policy on the likelihood of having medication available for use during at least four of the six months following initiation of therapy.(10) An interaction between the policy period and state represented the total policy effect. Other covariates included in the model were age, gender, race, and level of comorbidity. Model fit was assessed using likelihood statistics.(18)

Survival models similar to those described above were used to assess changes in the hazard of hospitalization or emergency room use during the 12 months following initiation of antidepressant therapy among patients initiating in the pre and post policy period in each state. We ran these models for all newly treated patients and for the subset of patients who had a evidence of depression or severe mental illness (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar diagnosis) at baseline. Further, we examined the subset of hospitalizations and emergency room visits with a psychiatric diagnosis (depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) or that occurred in a psychiatric inpatient facility. Model fit was assessed using the supremum test.(18)

We engaged an expert panel of clinical psychiatrists to provide an internal review of our study methods and our interpretation of the key findings. In addition, a draft of this report was provided to the director’s office at the Michigan Department of Community Health Medicaid Program prior to submission for publication. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

Table 1 shows the similarities in baseline demographic and other characteristics of the continuously enrolled cohort of dual enrollees in the study and comparison state. Overall, dual enrollees in the continuously enrolled and newly treated cohorts were similar across states.

Table 1.

Baselinea Characteristics of the Study and Comparison Cohorts

| Continuously Enrolled | New Treatment Episodes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Study Cohort (MI) (N=28,798) | Comparison Cohort (IN) (N=21,769) | Study Cohort (MI) (N=3,671) | Comparison Cohort (IN) (N=2,400) |

| Female (%) | 48.1 | 52.2b | 57.0 | 60.8 |

| Age group (%) | ||||

| ≤ 34 | 12.8 | 13.6 | 17.8 | 17.1 |

| 35–54 | 65.9 | 61.9 | 61.2 | 57.4 |

| 55–64 | 21.3 | 24.5b | 21.0 | 25.5b |

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 78.3 | 85.2 | 74.2 | 86.9 |

| Black | 19.1 | 13.2 | 22.9 | 11.4 |

| Other | 2.4 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 1.5 |

| Unknown | 0.2 | 0.2b | 0.03 | 0.2b |

| Antianxiety Use (%) | 25.4 | 27.5b | 31.0 | 35.0 |

| Antipsychotic Use (%) | ||||

| Typical | 12.3 | 11.2b | 11.8 | 9.4 |

| Atypical | 22.1 | 23.6b | 21.6 | 21.0 |

| Antimanic Use (%) | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.0 |

| Antidepressant Use (%) | 35.7 | 39.7b | ||

| SSRI/SNRI Only | 48.8 | 43.7 | ||

| SSRI/SNRI + TCA/Other | 23.0 | 28.8 | NA | NA |

| Tricyclics Only | 12.2 | 10.4 | ||

| Other Only | 14.1 | 14.8 | ||

| Any Other Combination | 1.9 | 2.3b | ||

| % with hospital admission | 18.7 | 22.6b | 28.5 | 30.3 |

Baseline period is 2001 for continuously enrolled cohort and 10 month before antidepressant initiation for the newly treated cohort.

p<0.001 between two states

Intended Effects

Rates of Antidepressant Use by Preferred Status

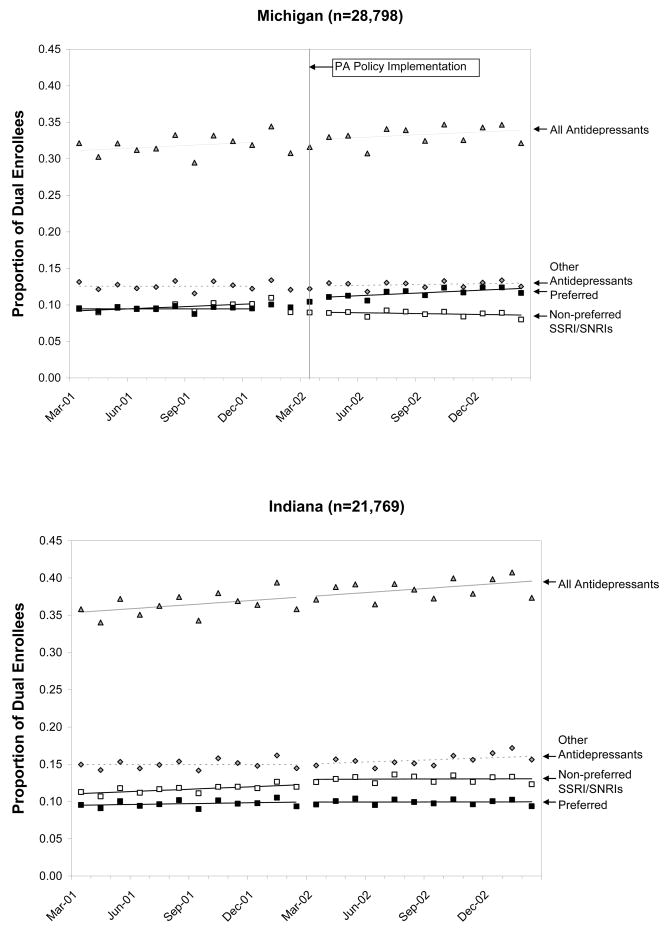

Among continuously enrolled dual enrollees in Michigan, there was a one percentage point absolute decrease in the use of non-preferred SSRI/SNRI agents attributed to the policy (p<0.0001), which was accompanied by a declining trend post policy (b= −0.001; p<0.001). These declines were largely offset by an increase in the use of preferred SSRI agents. In Indiana, there was a 2% (p<0.01) absolute increase in the use of non-preferred agents during the same period, accompanied by a slight decline in trend (b= −0.001; p<0.01). (Fig. 1) Changes in Michigan were driven by a dramatic shift away from non-preferred agents among newly treated patients. While more than 50% of newly treated patients initiated on these agents pre policy, fewer than 20% did so after the policy.[Data not shown]

Fig 1.

Monthly Prevalence of Antidepressant Use by Type of Drug in Each State

Unintended Effects

Rates of Therapy Initiation

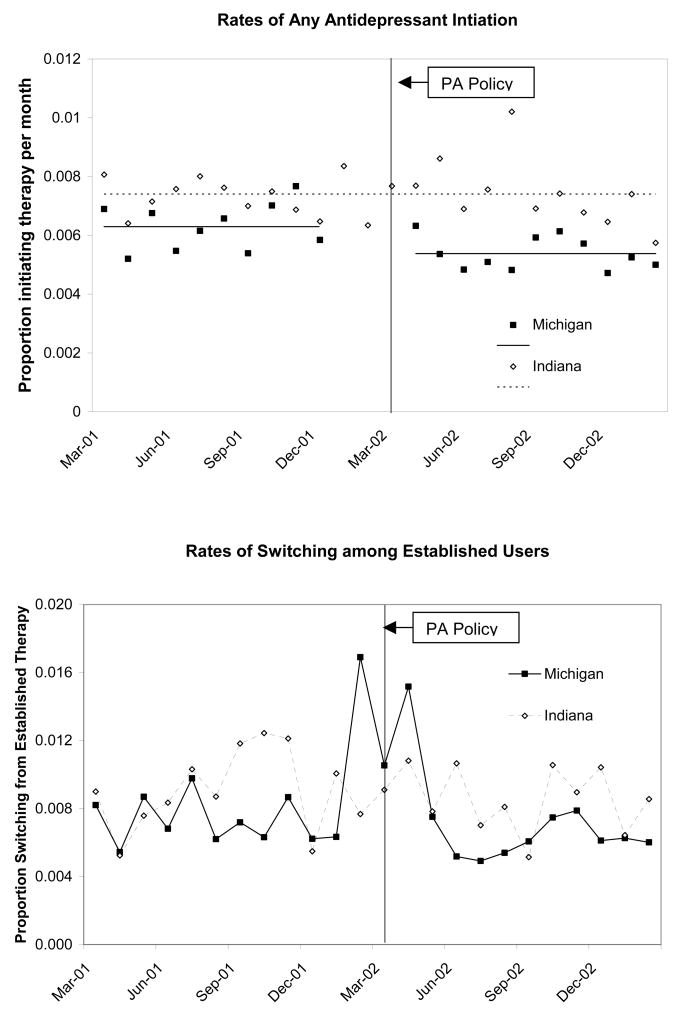

In Michigan, there was a slight decrease in the number of dual enrollees initiating any antidepressant therapy (e.g., SSRI/SNRI, tricyclics, buproprion) (9 per 10,000; p=0.021) immediately following the implementation of the PA policy that was largely driven by declines in SSRI/SNRI initiations. (Fig. 2, top) There was no change in the level or rate of antidepressant therapy initiation among dual enrollees in Indiana during this time. For the subgroup of dual enrollees with depression, we observed a slight declining trend in rates of antidepressant initiation in Michigan following the policy (5 per 10,000; p=0.005). (Data not shown) Trends in initiation of antidepressant therapy for this subgroup in Indiana were stable over time.

Fig 2.

Rates of Antidepressant Therapy Initiation (MI: 28,798, IN: 21,769) and Switching among Established SSRI/SNRI Users (MI: 14,638, IN: 10,398)

Switching from Current Therapy

Among the rolling cohort of established SSRI/SNRI users, (Fig 2, bottom) there was a visible increase in rates of switching therapy during policy implementation (the month before, during and immediately after). We modeled these trends using GEE models and found a two-fold higher risk of switching during the policy among dual enrollees in Michigan relative to Indiana overall [RR: 2.07; 95% CI:1.48, 2.88] and among those with depression [RR: 1.53 (1.01,2.32)]. (Table 2: col. 6) Dual enrollees established on non-preferred agents (approximately 49% of established users) had the highest odds of switching therapy [overall: 2.88 (1.87, 4.42); depression: 2.04 (1.22, 3.42)]. There was no evidence of increased risk during the remainder of the follow up period. (Data not shown)

Table 2.

| Outcome | Adjusted Odds Ratios | Risk Ratios (MI vs. IN) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michigan | Indiana | |||||

| Implementation (n=4,284) vs. Pre-policy (n=5,093)c | Post (n=5,261) vs. Pre-Policy | Implementation (n=2,930) vs. Pre-policy (n=3,633) | Post (n=3,835) vs. Pre-Policy | Implementation vs. Pre-policy | Post vs. Pre-Policy | |

| All Established Users | 2.43(1.99, 2.97)d | 0.97(0.81, 1.16) | 1.18(0.90, 1.54) | 1.00(0.82, 1.22) | 2.07(1.48, 2.88)d | 0.97(0.74, 1.26) |

| Using non-preferred agents prior to switche | 3.52(2.74, 4.51)d | 0.87(0.67, 1.14) | 1.22(0.86, 1.74) | 1.00(0.77, 1.30) | 2.88(1.87, 4.42)d | 0.87(0.60, 1.26) |

| Implementation (n=1,859) vs. Pre-policy (n=2,291) | Post (n=2366) vs. Pre-Policy | Implementation (n=1,461) vs. Pre-policy (n=1,890) | Post (n=1,986) vs. Pre-Policy | Implementation vs. Pre-policy | Post vs. Pre-Policy | |

| Established Users with Depression | 2.05(1.57, 2.67)d | 0.93(0.73, 1.17) | 1.34(0.97, 1.84) | 1.05(0.83, 1.33) | 1.53(1.01, 2.32)d | 0.88(0.63, 1.23) |

| Using non-preferred agents prior to switche | 2.98(2.16, 4.12)d | 0.84(0.60, 1.17) | 1.46(0.98, 2.18) | 1.05(0.77, 1.43) | 2.04(1.22, 3.42)d | 0.80(0.51, 1.27) |

SSRI=Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRI= serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Models control for age, gender, race, comorbidity and frequency of antidepressant use during the past six months

pre-policy: Mar 2002-Jan 2002; implementation period: Feb 2002–April 2002; post policy: May 2002–April 2003

p<0.05

Sample size of all established users using non-preferred agenda prior to switch in MI (pre policy: 2,490; implementation: 2,090; post policy: 2,236) and IN (pre policy: 1,857; implementation: 1,516; post policy 2,038); Established users with depression using non-preferred agents prior to switching medications in MI (pre policy: 1,131; implementation: 912; post policy: 1,038) and IN (pre policy: 993; implementation: 774; post policy: 1,076).

Discontinuities in Therapy among Newly Treated Patients

Comparing rates of switching/augmentation and discontinuation among newly treated dual enrollees in Michigan pre and post policy to those in Indiana, (Table 3A, col. 4) we found no evidence of greater risk of treatment disruptions in the study state overall [Switching/Augmentation: 1.02(0.78, 1.35); Discontinuation: 1.02(0.90, 1.17)] (Table 3A) or among those with a depression diagnosis [Switching/Augmentation: 1.30(0.85, 1.97; Discontinuation: 0.95(0.75, 1.21)].(Data not shown) Persistence with therapy was slightly higher in Michigan post policy, but was not statistically significant [Risk Ratio: 1.37 (0.86, 2.18)]. (Data not shown)

Table 3.

| Therapy Disruption Six Months Following Initiation |

Adjusted Hazard Ratio | Change in Michigan vs. Indiana Risk Ratios | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy vs. Pre-Policy Hazard (95% CI)c | |||

| Michigan (N=3,671) | Indiana (N=2,400) | ||

| All Newly Treated Patients | |||

| Switch/Augment to another SSRI/SNRI | 0.75 (0.57, 0.98)d | 0.77 (0.56, 1.05) | 0.97 (0.64, 1.47) |

|

| |||

| Switch/Augment to any antidepressant | 0.94 (0.78, 1.13) | 0.92 (0.75, 1.12) | 1.02 (0.78, 1.35) |

|

| |||

| Discontinuation of SSRI/SNRI therapy | 1.10 (1.01, 1.19)c | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) | 1.03 (0.91, 1.17) |

|

| |||

| Discontinuation of all antidepressants | 1.10 (1.01, 1.20)c | 1.08 (0.97, 1.19) | 1.02 (0.90, 1.17) |

|

| |||

| Adverse Events 12 Months Following Initiation | Adjusted Hazard Ratio | Change in Michigan vs. Indiana | |

| Policy vs. Pre-Policy Hazard (95% CI) | |||

| Michigan (N=3,671) | Indiana (N=2,400) | ||

|

| |||

| All Events | |||

| Emergency Room | 1.04 (0.95, 1.14) | 1.09 (0.98, 1.21) | 0.95 (0.83, 1.00) |

|

| |||

| Hospitalization | 1.00 (0.88, 1.13) | 0.90 (0.79, 1.04) | 1.11 (0.92, 1.33) |

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors only

Models controlled for age, gender, race, comorbidity

pre-policy: November 2000-August 2001; post-policy: March 2002 and December 2002

p<0.05

Hospitalization and Emergency Visits among Newly Treated Patients

Table 3B shows results from the survival models assessing time until emergency room (ER) visit and hospitalization in the 12 months following initiation of antidepressant therapy in the post versus pre policy period among dual enrollees in each state, and comparing these ratios across states. No statistically significant differences in the risk of an event were identified in the overall cohort [ER RR: 0.95 (0.83, 1.09); Hospitalization RR: 1.11 (0.92, 1.33)]. (Table 3B, col. 4) We found similar results for dual enrollees who had a depression diagnosis [ER RR: 0.94 (0.75, 1.18); Hospitalization RR: 1.09 (0.83, 1.43)] or a diagnosis of severe mental illness [ER RR: 0.96 (0.73, 1.25); Hospitalization RR: 1.08 (0.78, 1.48)] at baseline. Lastly, we observed no statistically significant changes in rates of psychiatric hospitalizations or emergency room visits. (Data not shown)

DISCUSSION

The PA policy for new users of SSRI and SNRI therapy in Michigan Medicaid was associated with a small shift in use toward preferred agents among dual enrollees. We found no evidence of discontinuities in medication use or greater risk of emergency room use or hospitalization among newly treated dual enrollees. However, the policy was associated with a small, but immediate decrease in the number of dual enrollees initiating on any antidepressant therapy and a decreasing trend in new starts among dual enrollees with a diagnosis of depression. Further, despite the intent of the policy to affect only new users, we also observed a short term increase in switching among dual enrollees already established on non-preferred SSRI and SNRI agents.

Our findings of a decrease in initial rates of therapy may indicate that the policy created a barrier to initial treatment. This is consistent with the Kaiser Family Foundation case study of the Michigan policy, which indicated that some Medicaid patients may have been turned away at the pharmacy after being prescribed a non-preferred agent without prior approval.(8) In addition, our results are consistent with those of McCombs and colleagues who found that removal of a prior authorization policy for antidepressants resulted in an increase in new treatment episodes.(19)

Increased rates of switching among established users may be explained by physician avoidance of the prior authorization process. Previous studies have identified administrative hassle associated with PA programs.(20) The short-lived nature of this effect may be indicative of physician learning and/or improved administrative processes within the state Medicaid program.

In contrast with our previous studies of PA policies for atypical antipsychotic and anticonvulsant therapy, we did not observe increased risk of therapy disruptions among newly treated dual enrollees in Michigan.(5) This difference may reflect greater similarities in efficacy and effectiveness among newer antidepressants relative to antipsychotic and anticonvulsant therapies.(21–24)

This study has several limitations that merit discussion. Because of incomplete ascertainment of diagnoses of depression in claims data,(25) we did not require patients in this study to have a depression diagnosis. However, our findings of lower rates of initial treatment and increased rates of short term switching in the overall population were mirrored in the subset of patients with a depression diagnosis, indicating potential impacts on access to quality care.

Our requirement of continuous enrollment may have reduced the generalizability of the study findings. We did not have explicit justification for our definition of new users. However, adjustments to definition (i.e., four months without any use versus six) did not change study results. Also, our measure of discontinuation may have been imprecise. However, sensitivity analyses around our definition of discontinuation of therapy (i.e., 30 vs. 45 vs. 60 days) did not affect study results.

In summary, our findings indicate that prior authorization policies among newly treated dual enrollees receiving SSRI and SNRI therapy may be effective in shifting market share without adverse consequences for treatment continuity. However, challenges in implementation may lead to unintended reductions in rates of initial treatment and short-term disruptions in treatment for established users, even among those with a clinical diagnosis of depression. To the extent that prior authorization policies create a barrier to initial treatment, particularly among dual enrollees with a depression diagnosis, they may reduce access to care as recommended in standard treatment guidelines. These findings indicate a need for frequent and systematic monitoring of prior authorization policies, like that employed in Michigan, to identify and mitigate potential unintended consequences for vulnerable dual enrollees.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute for Mental Health [Grant #: 5R01MH069776-03] and conducted at the Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention at Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care. Dr. Lu was supported by the Fellowship Program in Pharmaceutical Policy Research at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Trinacty’s time was supported by the Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention. NIMH had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Drs. Adams and Soumerai (principal investigator) had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

We gratefully acknowledge Drs. Carl Salzman, Anthony Rothschild, Daryl Tanski, and Alisa Busch for their clinical expertise and guidance, Jen Associates, Inc. for data processing, and Mai Manchanda for assisting with data acquisition and quality assurance.

References

- 1.Koyanagi C, Forquer S, Alfano E. Medicaid policies to contain psychiatric drug costs. Health Affairs. 2005;24(2):536–44. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huskamp HA, Stevenson DG, Donohue JM, Newhouse JP, Keating NL. Coverage and prior authorization of psychotropic drugs under Medicare Part D. Psychiatric Serv. 2007;58(3):308–10. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lexchin J. Effects of restrictive formularies in the ambulatory care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohue JM, Frank RG. Estimating Medicare Part D’s impact on medication access among dual eligible beneficiaries with mental disorders. Psychiatric Serv. 2007;58(10):1285–91. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Use of atypical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia in Maine Medicaid following a policy change. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008 May-Jun;27(3):w185–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.w185. Epub 2008 Apr 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott RA, Majumdar SR, Gillick MR, Soumerai SB. Benefits and consequences of the new Medicare drug benefit for the poor and the disabled. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(26):2739–2741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. [Accessed: October 31, 2003];Case study: Michigan’s Medicaid prescription drug benefit. 2003 January; www.kff.org.

- 8.Michigan Department of Community Health. [Accessed: July 18, 2008];Michigan Department of Community Health Releases update to preferred drug list. 2003 July 27; http://www.michigan.gov/mdch/0,1607,7-132-8347-71027--,00.html.

- 9.Croghan TW, Melfi CA, Crown WE, Chawla A. Cost-effectiveness of antidepressant medications. J Mental Health Policy Econ. 1998;1(3):109–117. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(1998100)1:3<109::aid-mhp15>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croghan TW, Melfi CA, Dobrez DG, Kniesner TJ. Effect of mental health specialty care on antidepressant length of therapy. Med Care. 1999;37(4 Suppl Lilly):AS20–AS23. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1128–1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hylan TR, Crown WH, Meneades L, et al. SSRI antidepressant drug use patterns in the naturalistic setting: a multivariate analysis. Med Care. 1999;37(4):AS36–AS44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Maclure M, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(9):854–864. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.9.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soumerai SB, Avorn J, Ross-Degnan D, Gortmaker S. Payment restrictions for prescription drugs under Medicaid: effects on therapy, cost, and equity. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(9):550–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708273170906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillings D, Makuc D, Siegel E. Analysis of interrupted time series trends: an example to evaluate regionalized perinatal care. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(1):38–46. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner A, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford; Oxford University Press: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using SAS: A Practical Guide. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCombs JS, Stimmel GL, Croghan TW. A retrospective analysis fo the revocation of prior authorization restrictions and the use of antidepressant medications for treating major depressive disorder. Clin Ther. 2002;24(11):1939–59. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilk JE, West JC, Rae DS, Rubio-Stipec M, Chen JJ, Regier DA. Medicare Part D prescription drug benefits and administrative burden in the care of dually eligible psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Serv. 2008;59(1):34–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Cacy TS. Efficacy and safety of second-generatino antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(6):415–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katzman MA, Tucco AC, McIntosh D, et al. Paroxetine versus placebo and other agents for depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(12):1845–59. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manschreck TC, Boshes RA. The CATIE schizophrenia trial: results, impact, controversy. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2007;15(5):245–258. doi: 10.1080/10673220701679838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johannssen Landmark C. Antiepileptic drugs in non-epilepsy disorders: relations between mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(1):27–47. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermann RC. Risk adjustment for mental health care. In: Iezzoni Lisa., editor. Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes. 3. Health Administration Press; Chicago: 2003. pp. 349–362. [Google Scholar]