Abstract

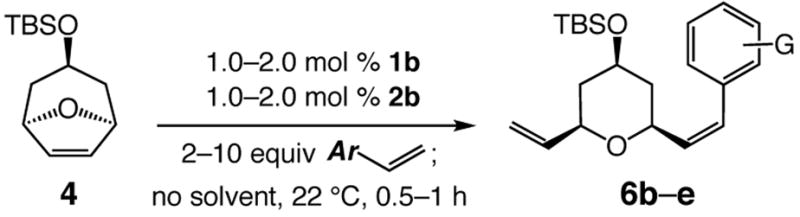

The first highly Z- and enantioselective class of ring-opening/cross-metathesis (ROCM) reactions is presented. Transformations are promoted in the presence of <2 mol % of chiral stereogenic-at-Mo monoaryloxide complexes, which bear an adamantylimido ligand and are prepared and used in situ. Reactions involve meso oxabicyclic substrates and afford the desired pyrans in 50–85% yield and in up to >98:<2 enantiomer ratio (er). Importantly, the desired chiral pyrans are thus obtained bearing a Z olefin either exclusively (>98:<2 Z:E) or predominantly (≥87:13 Z:E).

In spite of impressive advances accomplished during the past two decades, a number of unresolved issues limit the utility of catalytic olefin metathesis reactions.1 A notable shortcoming is the lack of methods that selectively furnish Z alkenes.2 Nearly all ring-opening/cross-metathesis (ROCM) reactions catalyzed by Mo or Ru complexes afford E olefins exclusively or predominantly.3,4 Only when the cross partner bears an sp-hybridized substituent (acrylonitrile or an enyne) are, at times, Z-alkenes favored.5 Effective solutions to the above critical problem require the development of structurally distinct catalysts. Herein, we present an approach to catalytic enantioselective ROCM processes6 that delivers Z-olefins exclusively (>98:<2 Z:E) or with high selectivity (≥87:13 Z:E) in 50–85% yield and up to >98:<2 enantiomer ratio (er). Transformations are promoted by <2 mol % of a chiral stereogenic-at-Mo complex.

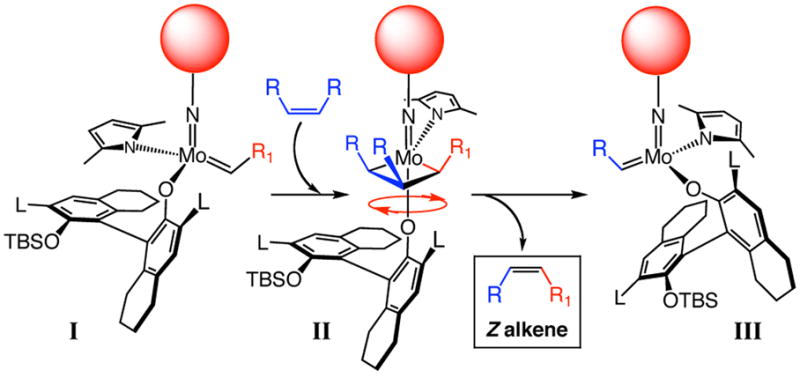

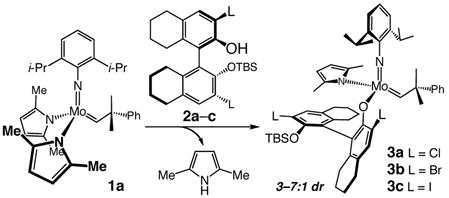

We recently introduced a class of olefin metathesis catalysts, which bear a stereogenic metal center (e.g., 3a–c, eq 1).7 Mo alkylidenes are synthesized by treatment of a bispyrrolide (e.g., 1a)8 with a mono-protected binaphthol (2a–c).7 In developing a Z-selective process, we reasoned that the flexibility of the Mo monoaryloxides should prove pivotal (Scheme 1). A sterically demanding but freely rotating aryloxide (around the Mo–O bond) in combination with a sufficiently smaller imido substituent (vs aryloxide) favors reaction through the syn alkylidene isomer (I, Scheme 1) and an all-cis metallacyclobutane (II, Scheme 1). Such pathways would produce Z-alkene products. In contrast, the hexafluoro-t-butoxides of an achiral Mo complex6 or the rigidly held chiral bidentate ligands of Mo diolates (delivering >98% E-olefins), 4a present a less significant steric barrier; trans-substituted metallacyclobutanes thus become energetically accessible.

Scheme 1.

Size Difference Between (Small) Imido and (Large) Aryloxide Ligands can Lead to High Z-Selectivity

|

(1) |

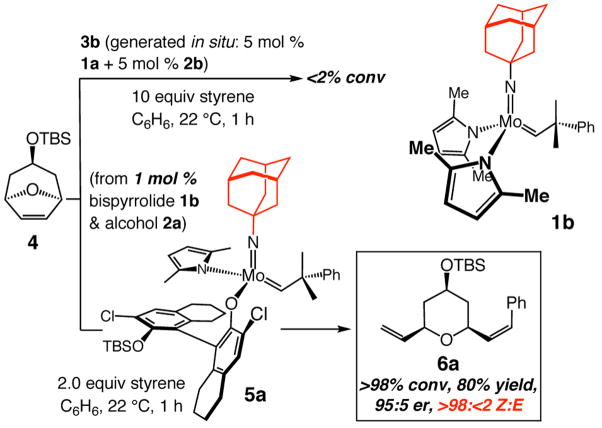

As the first step towards investigating the validity of the above hypotheses, we subjected oxabicycle 4 and styrene to chiral complex 3b, prepared through treatment of 5 mol % 1a with the corresponding aryl alcohol (2b); the chiral catalyst is typically used in situ. As shown in Scheme 2, conversion to the desired ROCM product is not observed (<2% in 1 h; minimal benzylidene formation by 400 MHz 1H NMR analysis). Such a finding led us to consider that the large arylimido unit in 3b, together with the sizeable aryloxide unit, might constitute a Mo complex that is too cumbersome to allow for formation of the requisite syn or anti alkylidene (cf. I) and subsequent cross-metathesis. We thus prepared 5a (Scheme 2; 3.0:1 dr), an alkylidene that bears the smaller adamantylimido unit. Such an alteration, we reasoned, would enhance activity as well as promote Z-selectivity. When oxabicycle 4 is treated with a solution containing styrene, 1 mol % of adamantylimido bispyrrolide (1b) and alcohol 2a, ROCM proceeds to >98% conversion within one hour, affording 6a in 80% yield and 95:5 er. Most importantly, the desired product is obtained exclusively as a Z olefin (>98:<2 Z:E).

Scheme 2.

Influence of Chiral Mo Complex’s Imido Group on Efficiency and E/Z- and Enantioselectivity of ROCM

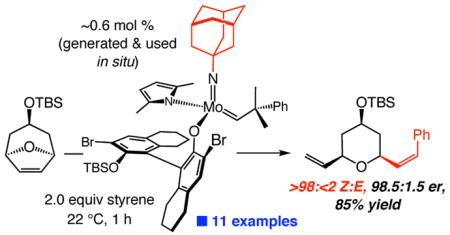

As the data summarized in entry 2 of Table 1 indicate, when Br-substituted chiral aryl alcohol 2b is used to prepare the catalyst (5b), ROCM is catalyzed with an equally exceptional level of Z-selectivity but with improved enantioselectivity (98.5:1.5 er vs 95:5 er with 2a as aryl alcohol in entry 1). Product from reaction with I-substituted 5c is obtained in higher enantiomeric purity (>98:<2 er, entry 3), affording Z-6a predominantly (95:5 Z:E). Reaction efficiency is reduced with 5c-d: ROCM proceeds to ~75% conversion, affording 6a in 60% and 57% yield, respectively. With 5d, catalyst synthesis is accompanied by generation of relatively inactive bisaryloxides (Table 1).9 That is, in all processes described, the amount of catalytically active monoaryloxide is less than that indicated by the mol % bispyrrolide and alcohol used. For example, the effective catalyst loading for the transformation in entry 2 of Table 1 is ~0.6 mol %. The lower Z-selectivity in the reaction with 5d (entry 4, Table 1) is likely due to E-selective ROCM that can be promoted, albeit inefficiently, by the unreacted achiral bispyrrolide (with 5 mol % 1b: 21% conv to 6a in 1 h, 3:1 E:Z). The low enantiomeric purity (≤70:30 er) of the E isomers supports the contention that such products largely arise from reactions promoted by achiral 1b.

Table 1. Z.

- and Enantioselective ROCM of 4 with Styrene (to Afford 6a) Catalyzed by Various Chiral Mo-Based Monoaryloxidesa

| entry | chiral complex; complex drb | mono-:bisaryloxide: bispyrrolide (%) | conv (%);b yield (%)c | erd | Z:Ee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5a(L=CI); 3.0:1 | 56:22:22 | >98; 80 | 95:5 | >98:<2 |

| 2 | 5b(L = Br); 2.2:1 | 62:8:30 | 98; 85 | 98.5:1.5 | >98:<2 |

| 3 | 5c(L=I);1.7:1 | 67:04:29 | 76; 60 | >98:<2 | 95:5 |

| 4 | 5d(L=F);nd | 07:47:46 | 75; 57 | 95:5 | 80:20 |

Performed with 1.0 mol % bispyrrolide and 1.0 mol % enantiomerically pure (>98% ee) aryl alcohol, 2.0 equiv styrene in C6H6 (or toluene), 22 °C, 1.0 h, N2 atm.

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures.

Yield of purified products.

Determined by HPLC analysis (details in the Supporting Information).

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures in comparison with authentic E-olefin isomer. nd = not determined.

Although stereoselectivity of olefin formation can vary as a function of the electronic or steric attributes of the cross partner, Z-alkenes remain strongly preferred (Table 2). Reaction with p-methoxy styrene and 5b as the catalyst affords pyran 6b with 94.5:5.5 Z:E selectivity (entry 1, Table 2). When p-trifluoromethyl styrene is used, 6c is isolated with complete Z-selectivity (>98:<2 Z:E, entry 3). It is plausible that the higher activity of the electron-rich alkene allows partial reaction through the sterically less favored anti alkylidene. It is noteworthy that, in spite of the increase in size of the aryl substituent in the reactions shown in entries 3–4 of Table 2, preference for the Z-alkene is only slightly diminished, presumably due to increased congestion in the derived all-syn metallacyclobutane (cf. II, Scheme 1).

Table 2. Z.

- and Enantioselective ROCM of 4 with Various Aryl Olefinsa

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Ar, Ar-olefin equiv | mol%1b; mol % 2b | time (h) | conv (%);b yield (%)c | erd | Z:Ee |

| 1 | b p-OMeC6H4; 2 | 1.0; 1.0 | 0.5 | 96; 80 | 97:3 | 94.5:5.5 |

| 2 | c p-CF3C6H4; 2 | 1.0; 1.0 | 1.0 | 96; 67 | 98:2 | >98:<2 |

| 3 | d o-BrC6H4; 10 | 2.0; 2.0 | 1.0 | 94; 50 | 99:1 | 89:11 |

| 4 | e o-MeC6H4;10 | 2.0; 2.0 | 1.0 | 97; 54 | 99:1 | 87.5:12.5 |

Performed with 1.0 mol % bispyrrolide and 1.0 mol % enantiomerically pure (>98% ee) aryl alcohol, 2.0 equiv styrene in C6H6 (or toluene), 22 °C, 1.0 h, N2 atm.

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures.

Yield of purified products.

Determined by HPLC analysis (details in the Supporting Information).

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures in comparison with authentic E-olefin isomer.

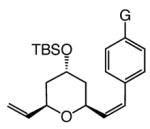

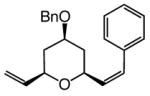

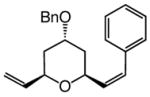

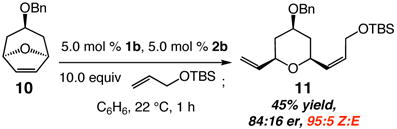

The findings in Table 3 illustrate that Mo-catalyzed ROCM reactions proceed with a range of substrates to afford trisubstituted pyrans efficiently (75–83% yield) and with high enantio- (92:8–98:2 er) and Z-selectivity (89:11–96:4 Z:E).10 The need for larger amounts of aryl olefin (10.0 equiv) and the higher catalyst loadings is likely because of the lower reactivity (reduced strain or intramolecular Mo chelation with OBn group) of bicyclic alkene diastereomers4c 7a–c (vs 4) and that of the corresponding benzyl ethers 8–9.

Table 3. Z.

- and Enantioselective ROCM of Oxabicycles with Aryl Olefinsa

| entry | product | mol%1b & 2b; olefin equiv | temp (°C); time (h) | conv (%);b yield (%)c | erd | Z:Ee | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

7a–c |

a G = H | 2.0; 10.0 | 22; 1.0 | 91; 83 | 97:3 | 96:4 |

| 2 | b G = OMe | 3.0; 10.0 | 22; 0.5 | 90; 80 | 96:4 | 89:11 | |

| 3 | c G = CF3 | 2.0; 10.0 | 22; 1.0 | 97; 81 | 98:2 | 94:6 | |

| 4 |

8 |

5.0; 10.0 | 60; 1.0 | 98; 75 | 92:8 | 95:5 | |

| 5 |

9 |

2.0; 10.0 | 22; 1.0 | 84; 80 | 92:8 | 91:9 |

Performed with 1.0 mol % bispyrrolide and 1.0 mol % enantiomerically pure (>98% ee) aryl alcohol, 2.0 equiv styrene in C6H6 (or toluene), 22 °C, 1.0 h, N2 atm.

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures.

Yield of purified products.

Determined by HPLC analysis (details in the Supporting Information).

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures in comparison with authentic E-olefin isomer.

We demonstrate that modular Mo adamantylimido complexes promote ROCM reactions with Z-selectivity levels that were previously entirely out of reach. Ongoing studies are focused on related transformations with other substrate classes. The initial finding illustrated in eq 2, involving an alkyl-substituted cross partner, bodes well for future investigations.

|

(2) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (Grant GM-59426) for financial support. I. I. is a Swedish Research Council postdoctoral fellow. We thank S. J. Meek and S. J. Malcolmson for helpful discussions and B. Li and K. Mandai for obtaining an X-ray structure. Mass spectrometry facilities at Boston College are supported by the NSF (DBI-0619576).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral, analytical data for all products (PDF). This material is available on the web: http://www.pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Hoveyda AH, Zhugralin AR. Nature. 2007;450:243–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For an early example of Z-selective (up to 3.2:1) ROCM, see: Randall ML, Tallarico JA, Snapper ML. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:9610–9611.

- 3.Schrader TO, Snapper ML. In: Handbook of Metathesis. Grubbs RH, editor. Vol. 2. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim: 2003. pp. 205–245. [Google Scholar]

- 4.La DS, Sattely ES, Ford JG, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7767–7778. doi: 10.1021/ja010684q.Van Veldhuizen JJ, Gillingham DG, Garber SB, Kataoka O, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12502–12508. doi: 10.1021/ja0302228.Gillingham DG, Kataoka O, Garber SB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12288–12290. doi: 10.1021/ja0458672.Funk TW, Berlin JM, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1840–1846. doi: 10.1021/ja055994d.Cortez GA, Baxter CA, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Org Lett. 2007;9:2871–2874. doi: 10.1021/ol071008h.. For application to natural product synthesis, see: Gillingham DG, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:3860–3864. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700501.

- 5.For example, see: Crowe WE, Goldberg DR. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5162–5163.Randl S, Gessler S, Wakamatsu H, Blechert S. Synlett. 2001:430–432.Hansen EC, Lee D. Org Lett. 2004;6:2035–2038. doi: 10.1021/ol049378i. For additional cases, see the Supporting Information.

- 6.Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:4592– 4633. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Malcolmson SJ, Meek SJ, Sattely ES, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2008;456:933–937. doi: 10.1038/nature07594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sattely ES, Meek SJ, Malcolmson SJ, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;131:943–953. doi: 10.1021/ja8084934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hock AS, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16373–16375. doi: 10.1021/ja0665904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Control experiments indicate that bisaryloxides derived from 1b and 3a–d promote <2% conv of 4 and styrene to 6a within 1 h (22 °C, C6H6).

- 10.Reactions proceed with similar efficiency and selectivity in toluene. For example, 6a and 9 are obtained in 84% yield, 98:2 er, 97.5:2.5 Z:E and 80% yield, 92:8 er and 91:9 Z:E, respectively, with toluene as the solvent.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.