Abstract

Lithium (Li)-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) has been attributed to the increased production of renal prostaglandin (PG)E2. Previously we reported that extracellular nucleotides (ATP/UTP), acting through P2y2 receptor in rat medullary collecting duct (mCD), produce and release PGE2. Hence we hypothesized that increased production of PGE2 in Li-induced NDI may be mediated by enhanced purinergic signaling in the mCD. Sprague-Dawley rats were fed either control or Li-added diet for 14 or 21 days. Li feeding resulted in marked polyuria and polydipsia associated with a decrease in aquaporin (AQP)2 protein abundance in inner medulla (∼20% of controls) and a twofold increase in urinary PGE2. When acutely challenged ex vivo with adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (ATPγS), UTP, or ADP, mCD of Li-fed rats showed significantly higher increases (50–130% over control diet-fed rats) in PGE2 production, indicating that more than one subtype of P2y receptor is involved. This was associated with a 3.4-fold increase in P2y4, but not P2y2, receptor mRNA expression in the inner medulla of Li-fed rats compared with control diet-fed rats. Confocal laser immunofluorescence microscopy revealed predominant localization of both P2y2 and P2y4 receptors in the mCD of control or Li diet-fed rats. Together, these data indicate that in Li-induced NDI 1) purinergic signaling in the mCD is sensitized with increased production of PGE2 and 2) P2y2 and/or P2y4 receptors may be involved in the enhanced purinergic signaling. Our study also reveals the potential beneficial effects of P2y receptor antagonists in the treatment and/or prevention of Li-induced NDI.

Keywords: collecting duct, P2 receptors, extracellular nucleotides, prostaglandin E2, cyclooxygenases, bipolar disorder, neurodegeneration, rat

lithium (Li) has been in clinical use for about half a century, mostly for the treatment of bipolar disorder, which affects up to 2% of the US population (33), with double the incidence in veterans. Mental depression and substance abuse, which are often encountered in posttraumatic stress disorder patients, such as war veterans, are known to predispose them to bipolar disorders. Despite the advent of newer drugs for bipolar disorders, Li is still an important medication in the psychiatric treatment regimen by virtue of the significantly lower suicidal risk in Li-treated patients (3). In addition, the advances in the pharmacotherapeutics of bipolar disorder over the past 10–15 yr have been predominantly in terms of tolerability and safety, with no new treatments being demonstrated to be more effective than Li (38). Furthermore, recent studies unraveled the neuroprotective effect of Li, thus making it a potential drug for the treatment of acute brain injury (e.g., stroke or ischemia), as well as chronic neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases (12, 35, 45, 53).

Whether it is for bipolar disorder or chronic neurodegenerative diseases, Li therapy is administered for long durations. However, therapeutic use of Li is often limited because of its adverse side effects on the kidney. In the clinic, patients on Li therapy often present with classical symptoms of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), which include polyuria, polydipsia, and reduced ability to concentrate urine and a lack of response to arginine vasopressin (AVP) administration (18). In animal models, Li-induced polyuria is associated with decreased protein abundance of AVP-regulated collecting duct water channel aquaporin (AQP)2 (31, 36). The AVP resistance in Li-induced NDI has been attributed to increased production of renal prostaglandin (PG)E2 (48). PGE2 is a potent antagonist of AVP action on collecting duct (19, 40, 44, 56). Administration of indomethacin, which inhibits PGE2 biosynthesis, ameliorates the polyuric condition, thus confirming the involvement of PGE2 in the Li-induced polyuria (2).

NDI is a debilitating condition that can result in severe fluid and electrolyte imbalance, especially in elderly patients, who exhibit impaired thirst mechanism (29, 34). Dehydrated NDI patients can develop hypernatremia, alterations in the level of consciousness, and hemodynamic instability from hypovolemia. Currently used therapeutic modalities, such as the combined use of a thiazide with a potassium-sparing diuretic (amiloride) or prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor (indomethacin or other cyclooxygenase inhibitors), are encountered with varying degrees of success as well as side effects, including Li intoxication (39, 41). Replacement of the current side effect-prone therapies with new drugs based on an improved understanding of molecular pathophysiology of Li-induced NDI should result in improved efficacy and fewer side effects.

One potential approach for the development of new therapies could be to decrease the production of renal PGE2, if we can identify the driving force(s) for the increased production of PGE2 by medullary collecting ducts in Li-induced NDI. In this context, we previously identified (54) that extracellular nucleotides (ATP/UTP), presumably acting through purinergic P2y2 receptor in normal rat medullary collecting duct, induce production and release of PGE2. We also reported (49) that this phenomenon is markedly enhanced in sucrose water-induced polyuria and blunted in the dehydrated condition. Hence, we hypothesized that purinergic signaling may play a key role in the pathogenesis of Li-induced NDI by enhancing the production of PGE2 by medullary collecting ducts and thus leading to a vasopressin-resistant state. In this study, using multiple approaches that involve ex vivo nucleotide-stimulated production of PGE2 by medullary collecting ducts, determination of expression of mRNA of P2y receptor subtypes in the inner medulla by quantitative RT-PCR, and confocal laser immunofluorescence localization of P2y2 and P2y4 receptor proteins in the inner medulla, we document that enhanced purinergic signaling in medullary collecting duct of Li-fed rats may potentially contribute to NDI.

METHODS

Experimental animals.

The animal protocols involved in these studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Department of Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Health Care System and the University of Utah. Specific pathogen-free male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA).

Li-induced NDI model.

Groups of rats were fed either a normal rat chow (control diet) or normal rat chow with added Li chloride (40 mmol/kg chow) with free access to drinking water for 14 or 21 days. Both diets were custom prepared by MP Biomedicals (Aurora, OH). Twenty-four-hour urine output and water intake were monitored before the experimental period, periodically during the Li feeding, and before euthanasia. At the end of the experimental period rats were euthanized by pentobarbital sodium overdose. Urine, blood, and kidney tissue samples were collected for analysis. Serum levels of Li were assayed on an automated clinical chemistry analyzer. Urine osmolality was measured by vapor pressure method on an osmometer (Wescor, Logan, UT). About 40 rats (n = 20 each for control and Li-added diet) were used in this study.

Determination of urinary PGE2 excretion.

PGE2 is not stable in the urine. It is rapidly converted to its 13,14-dihydro-15-keto metabolite. Hence, using a Prostaglandin E Metabolite Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), we converted urinary PGE2 to a single stable derivate and quantified it by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) as described previously (49, 50). The PGE2 metabolite content of the urine is expressed as nanograms per day or nanograms per milligram of creatinine (n = 8 urine samples each for control and Li-added diet groups). Creatinine was assayed by using a Creatinine Assay Kit from BioAssay Systems (Hayward, CA).

Measurement of nucleotide-stimulated release of PGE2 by medullary collecting ducts.

Fractions enriched in medullary collecting ducts were prepared and assayed for nucleotide-stimulated PGE2 release by the methods established in our laboratories (49, 50, 54). Briefly, freshly obtained inner medullas from control or Li-added diet-fed rats (n = 5 rats in each group) were digested by collagenase and hyaluronidase, followed by low-speed centrifugation and washings to separate the inner medullary collecting ducts from non-inner medullary collecting duct elements. The inner medullary collecting duct suspensions thus obtained were challenged with nucleotides. PGE2 released into the medium was assayed with an EIA kit (Cayman Chemical) after the medullary collecting ducts were pelleted by centrifugation. The values obtained for PGE2 in the incubations were normalized to the protein contents of the respective pellets. Protein was quantified by using a Coomassie Plus Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR assays on inner medullary samples.

This was performed as described previously with minor modifications (28, 50). Briefly, total RNA from the inner medullas of control or Li-added diet-fed rats (n = 4 rats in each group) was isolated by the TRIzol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to manufacturer's recommendations. Traces of genomic DNA in the extracted RNA samples were digested by DNase treatment (DNase I, amplification grade, Invitrogen), followed by the inactivation of DNase by EDTA. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription with SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen). cDNA was quantified by real-time amplifications on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Foster City, CA) with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and AmpliTaq Gold. Table 1 shows the nucleotide sequences of the primer pairs used in PCR. The DNA was amplified for 40 cycles by setting the annealing temperature to 60°C. Specificity of amplifications was determined by sequencing PCR products. The expression of P2y1, P2y2, P2y4, and P2y6 receptors was computed relative to the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of primer pairs used in PCR

| Gene | Accession No. | Primer Position | Primer Sequence | Amplicon Size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2y1 | NM_012800 | 1235–1254 | ACGTCAGATGAGTACCTGCG | 289 |

| 1504–1523 | CCCTGTCGTTGAAATCACAC | |||

| P2y2 | NM_017255 | 1270–1293 | ACCCGCACCCTCTATTACTCCTTC | 129 |

| 1376–1399 | AGTAGAGCACAGGGTCAAGGCAAC | |||

| P2y4 | NM_031680 | 263–284 | TGTTCCACCTGGCATTGTCAG | 294 |

| 537–556 | AAAGATTGGGCACGAGGCAG | |||

| P2y6 | NM_057124 | 644–665 | TGCTTGGGTGGTATGTGGAGTC | 339 |

| 960–982 | TGGAAAGGCAGGAAGCTGATAAC | |||

| β-Actin | NM_031144.2 | 18–37 | CACCCGCGAGTACAACCTTC | 207 |

| 205–224 | CCCATACCCACCATCACACC |

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of inner medullas.

This was performed per the methods established in our laboratories (11, 21). Briefly, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded kidney sections (20-μm thickness) from control or Li-added diet-fed rats (n = 4 rats in each group) were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and treated with Dako Antigen Retrieval reagent (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA). The sections were then permeabilized by Triton X-100 treatment, followed by incubation with Image-iT FX Signal Enhancer (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to P2y2 or P2y4 were used in conjunction with Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). P2y2 receptor antibody was raised and characterized by us (27, 28). It is directed to a COOH-terminal peptide sequence. P2y4 receptor antibody was purchased from Novus Biological (Littleton, CO). According to the manufacturer, it was raised against the first cytoplasmic domain of human P2y4 receptor, which has 67% rat identity and 80% rat homology. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide. Confocal laser microscopy was performed with a Nikon E800 upright microscope with Pan Fluor oil immersion lenses. A Simple Personal Confocal Image program (PCI, Compix, Cranberry Township, PA) was used to acquire digital images. Cy5 was detected with a red HeNe laser at 633 nm.

Statistical analysis.

Quantitative data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between the means of two groups were analyzed by unpaired t-test. Differences among the means of more than two groups were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the assessment of differences by Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of rat model of Li-induced NDI.

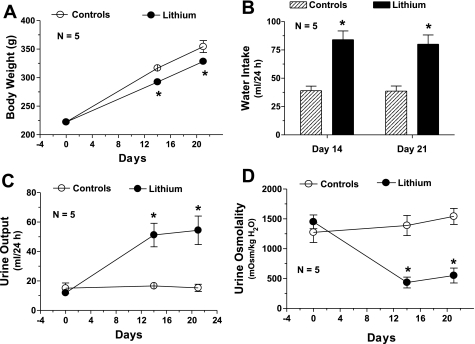

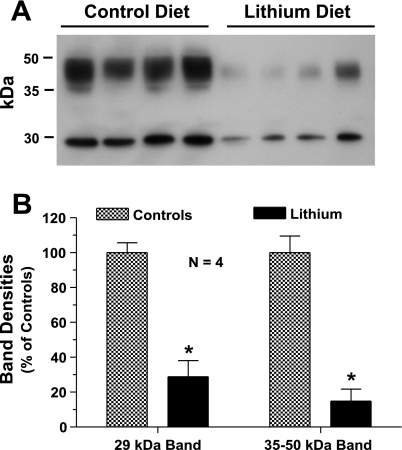

We have chosen a diet containing 40 mmol of Li chloride per kilogram of food because this concentration of Li when fed to rats up to 4 wk was shown to induce NDI in animals, mimicking the clinical condition seen in patients, without causing overt Li toxicity (31). Figure 1 shows the characterization of this Li model with respect to polydipsia and polyuria. Compared with the rats on regular diet, Li-fed rats showed 1) statistically significant smaller increases in body weight (Fig. 1A); 2) approximately twofold increase in water consumption (Fig. 1B); 3) two- to threefold increase in urine output (Fig. 1C); and a comparable threefold decrease in urine osmolality (Fig. 1D) on days 14 and 21. The severe polydipsia and polyuria in Li-fed rats were associated with marked decreases in protein abundance of AVP-regulated water channel AQP2 in inner medulla. The abundance of 29-kDa native AQP2 protein molecule in Li-fed rats decreased to ∼20% of that in the control group, whereas the abundance of glycosylated forms of AQP2 (35–50 kDa) was decreased to ∼15% of the control group on day 21 (Fig. 2). The decease in the observed changes in the parameters studied here are quite comparable to the results published by other investigators using a similar regimen of Li feeding (31, 36). Furthermore, Li levels in the blood of rats fed Li-added diet were 1.11 ± 0.07 (n = 8) and 1.18 ± 0.05 (n = 8) mmol/l after 14 and 21 days, respectively. These values are within the therapeutic range seen in patients on Li therapy (0.5–1.5 mmol/l). Thus our model mimics the clinical condition of Li therapy and does not result in overt Li toxicity. Since the observed changes in water consumption, urine output, urine osmolality, and blood Li levels were not significantly different between day 14 and day 21, the following experiments focused on effects of the Li-added diet for 14 days.

Fig. 1.

Polydipsia and polyuria associated with lithium (Li) feeding. Groups of Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 5/group) were fed control or Li-added diet for 21 days. Water intake and urine output were monitored periodically. Body weight (A), water intake (B), urine output (C), and urine osmolality (D) in the 2 groups on days 0, 14, and 21 are shown. Results are means ± SE (n = 5). *Significantly different from corresponding value in control diet group. Mean values of urine output and urine osmolality in Li-fed rats on day 14 and day 21 are not significantly different from each other.

Fig. 2.

Decreased protein abundance of aquaporin (AQP)2 associated with Li feeding. Groups of Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 4/group) were fed control or Li-added diet for 21 days and then euthanized. Inner medullas were processed for the determination of AQP2 protein abundance by Western blotting. A: AQP2 protein bands as visualized by Western blotting. B: densitometry values of 29-kDa and 35- to 50-kDa protein bands of AQP2 water channel seen in A. The sharp 29-kDa band corresponds to the native AQP2 protein molecule, whereas the smear from 35 kDa to 50 kDa represents the various glycosylated forms of AQP2 molecule. Results are means ± SE (n = 4). *Significantly different from corresponding value in control diet group.

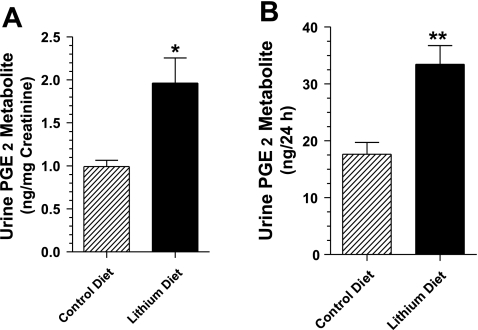

Urinary excretion of PGE2 metabolite.

PGE2 in the urine is not stable. Hence we converted it to a stable metabolite and assayed the metabolite content of the urine samples. Figure 3 shows that the PGE2 metabolite content in Li-fed rats is about twofold higher compared with rats fed the control diet. This is seen for both nanograms per milligram of urinary creatinine and nanograms per 24 h. These data, which support the earlier findings by other investigators (42), indicate that in our model of Li-induced NDI there is also increased production of renal prostaglandins.

Fig. 3.

Urinary excretion of prostaglandin (PG)E2 metabolite in rats fed control or Li-added diet for 14 days. Twenty-four-hour urine samples were collected from rats fed control or Li-added diet (n = 8/group) and processed for the assay of PGE2 metabolite. A: urinary PGE2 metabolite expressed as nanograms per milligram of creatinine. B: urinary excretion of PGE2 metabolite expressed as nanograms per 24 h. Results are means ± SE (n = 8). *P < 0.006, **P < 0.002 compared with corresponding mean values in control diet group.

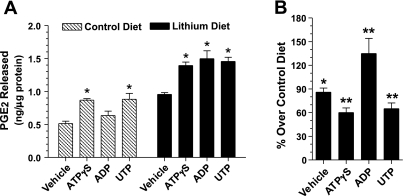

Nucleotide-stimulated release of PGE2 by inner medullary collecting duct.

To validate our hypothesis that purinergic signaling may play a key role in the pathogenesis of Li-induced NDI, we examined whether nucleotide-stimulated PGE2 release by inner medullary collecting ducts is enhanced in Li-induced NDI. In preliminary experiments we examined the adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (ATPγS)-stimulated release of PGE2 by freshly prepared fractions enriched in inner medullary collecting ducts from rats fed control or Li-added diets for 14 or 21 days. We observed that at both time points ATPγS, the universal P2y receptor agonist, caused enhanced PGE2 release by inner medullary collecting ducts of Li-fed rats compared with control diet-fed rats. Furthermore, at both time points, the magnitude of the purinergic-driven enhanced release of PGE2 in Li-fed rats was comparable (data not shown). Hence in the following experiments we studied the effect of feeding the Li-added diet for 14 days only. In addition, we used other P2y receptor agonists, namely UTP and ADP, to understand the nature of the P2y receptor subtype involved. In these experiments, medullary collecting ducts from control diet-fed rats released significantly higher amounts of PGE2 into the incubation medium when stimulated with 50 μM ATPγS or UTP, but not ADP (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, medullary collecting ducts from Li-fed rats released significant amounts of PGE2 into the incubation medium when stimulated by ATPγS, UTP, and ADP (Fig. 4A) compared with the vehicle group. Furthermore, the absolute amounts of PGE2 released by these three nucleotides in Li-fed rats were comparable (Fig. 4A) and were not significantly different from one another. In addition, the amounts of PGE2 released by the medullary collecting ducts of Li-fed rats, both under basal conditions (vehicle) and in response to the three nucleotides, were significantly higher compared with the corresponding releases in the control rats (Fig. 4B). Thus these findings suggest that enhanced purinergic-driven PGE2 release by inner medullary collecting ducts may be an early phenomenon in Li-induced NDI, which runs in parallel to the development of polydipsia, polyuria, and rise in blood Li levels. In addition, since ADP also elicited enhanced PGE2 release by inner medullary collecting ducts of Li-fed rats, it is possible that P2y receptor subtype(s) other than P2y2 may also be a key player in Li-induced NDI.

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide-stimulated PGE2 release by inner medullary collecting duct preparations from rats fed control or Li-added diet for 14 days. Fractions enriched in medullary collecting duct were freshly prepared by pooling inner medullas (n = 5 rats/group). Aliquots of fractions were warmed up to 37°C before challenging with each nucleotide at 50 μM for 20 min. Reactions were stopped by adding chilled buffer. PGE2 released into the medium was assayed and normalized to the protein contents of the respective incubations. Results are means ± SE of triplicate incubations for each condition. A: absolute amounts of PGE2 released as nanograms per milligram of protein under each condition. B: PGE2 released by the medullary collecting ducts of Li-fed rats as % over corresponding PGE2 release by control diet-fed rats. Statistical analysis by ANOVA: A, control diet group: *mean values in adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (ATPγS) and UTP incubations significantly different from mean value in corresponding vehicle incubations (P < 0.01). A, Li diet group: *mean values in ATPγS, ADP, and UTP incubations significantly different from mean values in corresponding vehicle incubations (P < 0.01). B: *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001.

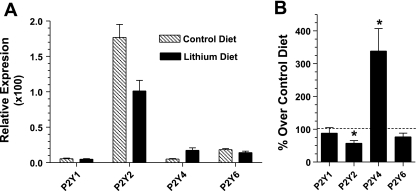

Expression of P2y receptor subtypes in the inner medulla.

The qualitative and quantitative differences observed between the inner medullary collecting ducts from control and Li diet-fed rats after nucleotide-induced PGE2 release suggested the involvement of more than one subtype of P2y receptor in Li-fed rats (Table 2). Hence we examined the potential changes in receptor expression by real-time RT-PCR with RNA extracted from the inner medullas. We choose to determine the relative expression of P2y1, P2y2, P2y4, and P2y6 receptors, because these four receptors are coupled to the phosphoinositide signaling pathway and thus are relevant for this study on NDI (Table 2). The results show that in rats fed control diet P2y2 is the predominant P2y receptor subtype expressed in the inner medulla, followed by P2y6 (Fig. 5A). However, after Li diet for 14 days, P2y2 receptor expression was decreased to ∼57%, associated with a 3.4-fold (340%) increase in the expression of P2y4 receptor relative to the rats on control diet (Fig. 5B). However, in terms of absolute quantity, the P2y2 receptor remained the predominant P2y receptor subtype even in Li-fed rats. The relative expression of P2y1 and P2y6 receptors did not change after Li feeding. Sequencing of PCR products established the specificity of amplifications for P2y receptors by providing a 98–99% match to the target sequence. Thus these data suggest that both P2y2 and P2y4 receptors may be involved in the enhanced production of PGE2 by inner medullary collecting ducts in Li-induced NDI.

Table 2.

Agonist potency and signal transduction mechanisms of P2y1, P2y2, P2y4, and P2y6 receptors

| Subtype | Amino Acids | Agonist Potency | Signal Transduction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2y1 | 362 | 2-MeS-ATP≥ATP >> ADP | Gq/G11;PLC-β↑ |

| P2y2 | 373 | UTP≥ATP > ATPγS >> 2-MeS-ATP | Gq/G11;(Gi/G0?);PLC-β↑ |

| P2y4 | 352 | UDP = UTP > ATP = ADP | Gq/G11(Gi?);PLC-β↑ |

| P2y6 | 379 | UDP > UTP > ADP >2-MeS-ATP >>> ATP | Gq/G11andGs;PLC-β↑ |

Fig. 5.

Relative expression of P2y receptor subtypes in the inner medullas of rats fed control or Li-added diets for 14 days. Inner medullas were collected from rats fed control or Li-added diet (n = 4 rats/group). RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and the cDNA obtained was amplified with specific primer pairs for P2y1, P2y2, P2y4, P2y6, or β-actin and a real-time PCR approach. Expression levels of P2y receptor subtypes were normalized to that of β-actin. A: relative expression of P2y receptor subtypes in rats fed control or Li-added diets. B: mean values of relative expression of P2y receptor subtypes in Li-fed rats as % of corresponding mean values in control diet-fed rats. Results are mean ± SE (n = 4). B: *significance level of P < 0.02.

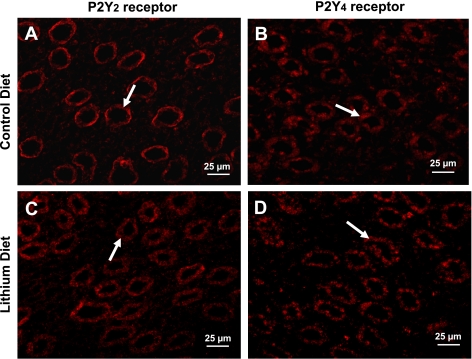

Immunofluorescence localization of P2y2 and P2y4 receptors in inner medulla.

Since RT-PCR experiments showed a large increase in the relative expression of P2y4 receptor in the inner medullas of Li-fed rats, we performed confocal laser immunofluorescence microscopy to examine the cellular localization of this receptor protein in the inner medulla. Comparisons between P2y2 and P2y4 were also made. As shown in Fig. 6, the distribution of P2y4 receptor protein is similar to that of P2y2 receptor, i.e., predominantly in collecting ducts, in rats fed control or Li-added diets. In addition, differences in the subcellular distribution of both P2y2 and P2y4 receptors in control and Li-fed rats were observed. However, these aspects are not probed further in this communication. Thus the findings from the confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, when taken in conjunction with data from the nucleotide-stimulated PGE2 release by inner medullary collecting ducts and the quantitative RT-PCR experiments on inner medulla, suggest the potential involvement of both P2y2 and P2y4 receptors in the enhanced purinergic signaling in Li-induced NDI.

Fig. 6.

Confocal immunofluorescence localization of P2y2 and P2y4 receptor proteins in the inner medullas of rats fed control or Li-added diets for 14 days. Kidney sections were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy with specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies to P2y2 or P2y4 receptors in conjunction with Cy5-conjugated donkey rabbit IgG. Cy5 was detected with a red HeNe laser at 633 nm. A and C: representative profiles for P2y2 receptor in control and Li diet-fed rats, respectively. B and D: representative profiles for P2y4 receptor in control and Li diet-fed rats, respectively. Sections used for generating A and B were obtained from the same block of paraffin-embedded kidney from a rat fed control diet. Similarly, sections used for generating C and D were obtained from the same block of paraffin-embedded kidney from a rat fed Li-added diet. Arrows indicate red fluorescence of Cy5 in medullary collecting duct. Images only depict localization of P2y2 and P2y4 receptor proteins in the inner medullary structures, and the intensity of the fluorescence does not correspond to the levels of their protein abundance.

DISCUSSION

Although increased production of renal PGE2 has been implicated in the polyuria of Li-induced NDI, the driving force for this is not known. Using a classical model of Li-induced NDI, we documented 1) markedly enhanced nucleotide-driven PGE2 release by the medullary collecting duct; 2) potential involvement of P2y2 and/or P2y4 receptors in the enhanced PGE2 release by medullary collecting duct; 3) marked increase in the expression of P2y4 receptor mRNA in the inner medulla; and 4) predominant localization of P2y2 and P2y4 receptor proteins in the medullary collecting duct. Together, these data suggest that purinergic signaling may play a previously unidentified potential role in the genesis of polyuria of Li-induced NDI by driving the increased production of PGE2 by medullary collecting ducts.

Efficient transport of water, sodium, and urea by the nephron, which is controlled by AVP, is crucial for the urinary concentration mechanism (15). The role of purinergic signaling in opposing the action of AVP on the renal transport of water and solutes is increasingly being recognized (8, 32, 46, 47, 52, 55). In a series of studies in rat models we established the potential role of P2y2 receptor in antagonizing the action of AVP on medullary collecting duct (26–28, 49, 50, 54). Recently, using P2y2 receptor gene knockout mice, we documented (57) that purinergic signaling may play a potential overarching role in balancing the effect of AVP on the urinary concentration mechanism.

Previously we demonstrated (54) that inner medullary collecting ducts of normal rats, when stimulated by ATPγS or UTP, produce and release PGE2, which is consistent with the presence of P2y2 receptor. Interestingly, however, in the present study when rats were fed Li-added diet for 14 days, the nucleotide-stimulated PGE2 release revealed both qualitative and quantitative differences compared with the PGE2 release by medullary collecting duct of control diet-fed rats. Qualitatively, the medullary collecting duct from Li-fed rats responded to ADP, in addition to ATPγS and UTP (Fig. 4B), suggesting the potential involvement of P2y6 and/or P2y1 receptor subtypes as well, in addition to P2y2 receptor (Table 2). Quantitatively, the amounts of PGE2 released by the medullary collecting duct of Li-fed rats in response to the three nucleotides tested were significantly higher than the corresponding amounts in control diet-fed rats (Fig. 4B). Together these two findings indicate that Li feeding sensitizes the purinergic signaling in the medullary collecting ducts to extracellular nucleotides. In light of these ex vivo data generated by the use of freshly prepared fractions enriched in inner medullary collecting ducts, it is reasonable to deduce that the twofold increase in urinary PGE2 metabolite seen in Li-induced NDI may be due to increased production of PGE2 by medullary collecting ducts in vivo.

The observed qualitative shift in the purinergic signaling in medullary collecting duct following Li feeding is associated with a marked 3.4-fold increase in the mRNA expression of P2y4 receptor, suggesting the potential involvement of this receptor in Li-induced NDI (Fig. 5B). However, the mRNA expression of P2y6 receptor, the other potential candidate based on nucleotide-stimulated release of PGE2, was not changed by Li feeding. Despite the observed significant decrease in expression, P2y2 receptor still remained the predominant P2y receptor (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, preliminary data we obtained showed that genetic deletion of P2y2 receptor in mice results in marked resistance (∼50%) to Li-induced polyuria, indicating the potential involvement of P2y2 receptor in the genesis of NDI. In addition, it is well known that the activity of G protein-coupled receptors, such as the P2y receptors, is regulated by a variety of receptor-associated factors independent of receptor expression itself (10, 13, 20). Hence at this stage we cannot rule out the lack of involvement of P2y2 receptor in Li-induced NDI based on its mRNA expression alone.

After documenting the potential involvement of P2y4 receptor by functional analysis and mRNA expression, we then turned to examine the expression and localization of P2y4 receptor protein in the inner medulla by confocal laser immunofluorescence microscopy and compared them with the expression and localization of P2y2 receptor. We observed that, similar to P2y2 receptor, P2y4 receptor protein is expressed in the medullary collecting duct. However, the subcellular distribution of these two proteins apparently differed in control versus Li-fed rats. Pending more detailed studies, in the present work we did not pursue these aspects further.

Less is known about the role of P2y4 receptor in the collecting duct biology compared with advances in P2y2 receptor biology. Recently Wildman and associates (55), using an approach of whole cell patch clamp of principal cells of split-open collecting ducts from sodium-restricted rats, found that activation of P2y2 and/or P2y4 receptors inhibited the activity of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). In parallel, they found that P2y4 mRNA levels were insignificant in the microdissected sodium-repleted rats, whereas there was a marked abundance of P2y4 receptor mRNA in sodium-restricted rats (55). Hence it is possible that, at least under pathophysiological conditions, the P2y2 and P2y4 receptors may function synergistically.

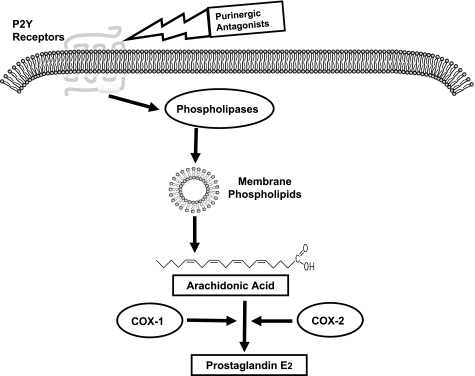

Increased expression of cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2) in Li-induced NDI has been implicated in the increased production of PGE2 (30, 42). However, the availability of free arachidonic acid, the substrate, itself is considered by many investigators as the initial and often the rate-limiting step in the production of PGE2 (4, 22, 37). In this context, our study demonstrates that enhanced purinergic signaling in the medullary collecting duct following Li feeding may hold the key for the increased production of free arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids via phospholipases as depicted in Fig. 7. The increased expression of COX enzymes in Li-induced NDI may only partially facilitate the rapid formation of PGE2 from the increased availability of free arachidonic acid due to enhanced purinergic signaling.

Fig. 7.

The cascade of events in the biosynthesis of PGE2 and the potential utility of purinergic antagonists to block the increased production of PGE2 in Li-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. The availability of free arachidonic acid is often the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of PGE2 by cyclooxygenases (COX-1 or COX-2). The release of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids is critically dependent on the activity of phospholipases. The activation of phospholipases is in turn dependent on signal transduction through G protein-coupled receptors that act through phosphoinositide signaling pathway, such as the P2y purinergic receptors. Hence, blocking the activity of P2y receptors by the use of specific receptor antagonists should effectively decrease the release of free arachidonic acid for the synthesis of PGE2 by COX-1 or COX-2, and thus ameliorate Li-induced polyuria.

Finally, the long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as indomethacin, and COX-2-specific inhibitors (celecoxib or rofecoxib), which suppress PGE2 production by directly inhibiting cyclooxygenases, is known to cause permanent renal toxicity and damage and/or elevated serum Li to toxic levels (6, 16, 39, 41). Hence replacement of the current side effect-prone drugs with new drugs based on improved understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of Li-induced NDI should result in improved efficacy and fewer side effects in the clinic. This work represents the first step in that direction. The potential role of purinergic signaling in the enhanced production and release of PGE2 by the medullary collecting duct in Li-induced NDI uncovered by us opens the possibility of targeting purinergic signaling by specific receptor antagonists to decrease the PGE2 production in Li-induced NDI as depicted in Fig. 7.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Project (to B. K. Kishore), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-61183 (to B. K. Kishore), the National Kidney Foundation of Utah and Idaho (to B. K. Kishore), and the resources and facilities at the Department of Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Health Care System.

DISCLOSURE

The proprietary information presented here is protected by an international patent under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT/US2005/038231) and was published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WO/2006/066679).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kenneth E. Hill for his help in confocal microscopy and Rujia Sun and Andrew Hemmert for technical assistance in the initial stages.

Parts of this work were presented at Experimental Biology 2005 (April 2005, San Diego, CA) (51), the Purines 2008 Meeting (June-July 2008, Copenhagen, Denmark) (25), and the 41st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Nephrology (November 2008, Philadelphia, PA) (24) and appeared as printed abstracts in the proceedings of those meetings.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jackobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology. LVIII. Update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev 58: 281–341, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen HM, Jackson RL, Winchester MD, Deck LV, Allon M. Indomethacin in the treatment of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Arch Intern Med 149: 1123–1126, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldessarini RJ, Pompili M, Tondo L. Suicide in bipolar disorder. Risks and management. CNS Spectr 11: 465–471, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bomalaski JS, Clark MA. Phospholipase A2 and arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 36: 190–198, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonvalet JP, Pradelles P, Farman N. Segmental synthesis and actions of prostaglandins along the nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F377–F387, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravo R, Egger SS, Crespo S, Probst WL, Krahenbuhl S. Lithium intoxication as a result of interaction with rofecoxib. Ann Pharmacother 38: 1189–1193, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breyer MB, Breyer RM. Prostaglandin E receptors and the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F12–F23, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucheimer RE, Linden J. Purinergic regulation of epithelial transport. J Physiol 555: 311–321, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnstock G Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev 87: 659–797, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabrera-Vera TM, Vanhauwe J, Thomas TO, Medkova M, Preininger AP, Masón MR, Hamm HE. Insights into G protein structure, function, and regulation. Endocr Rev 24: 765–781, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson NG, Hill KE, Tsunoda I, Fujinami RS, Rose JW. The pathologic role for COX-2 in apoptotic oligodendrocytes in virus induced demyelinating disease: implications for multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 174: 21–31, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuang DM Neuroprotective and neurotropic actions of the mood stabilizer lithium: can it be used to treat neurodegenerative diseases? Crit Rev Neurobiol 16: 83–90, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vries L, Zheng B, Fisher T, Elenko E, Farquar MG. The regulator of G protein signaling family. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 40: 235–271, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecelbarger CA, Maeda Y, Gibson CC, Knepper MA. Extracellular ATP increases intracellular calcium in rat terminal collecting duct via a nucleotide receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F998–F1006, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenton RA, Knepper MA. Mouse model and the urinary concentrating mechanism in the new millennium. Physiol Rev 87: 1083–1112, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frölich JC, Leftwich R, Ragheb M, Oates JA, Reimann I, Buchanan D. Indomethacin increases plasma lithium. Br Med J 1: 1115–1116, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimura A, Ohashi K, Ebihara A. Influence of repeated administration of lithium on urinary excretion of prostaglandins in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol 57: 565–569, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gitlin M Lithium and the kidney: an update review. Drug Saf 20: 231–243, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han JS, Maeda Y, Ecelbarger C, Knepper MA. Vasopressin-independent regulation of collecting duct water permeability. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 266: F139–F146, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermans E Biochemical and pharmacological control of the multiplicity of coupling at G protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther 99: 25–44, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill KE, Zollinger LV, Watt HE, Carlson NG, Rose JW. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in chronic active multiple sclerosis plaques: distribution, cellular expression and association with myelin damage. J Neuroimmunol 151: 171–179, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirabayashi T, Shimizu T. Localization and regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta 1488: 124–138, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judge JP, Kohan DE, Carlson NG, Nelson RD, Kishore BK. Mice with genetic deletion of P2Y2 receptor are markedly resistant to lithium-induced polyuria (Abstract). J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 31A, 2006.16338965 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishore BK, Carlson NG, Kamareth CD, Zhang Y. Potential involvement of P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors in lithium-induced polyuria (Abstract). J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 582A, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishore BK, Carlson NG, Raoul RD, Kohan DE. Renal purinergic system—a potential drug target for the treatment of lithium-induced diabetes insipidus (Abstract). Purinergic Signal 4: S100, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kishore BK, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Extracellular nucleotide receptor inhibits AVP-stimulated water permeability in inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 269: F863–F869, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishore BK, Ginns SM, Krane CM, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Cellular localization of P2Y2 purinoceptor in rat inner medulla and lung. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F43–F51, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kishore BK, Krane CM, Miller RL, Shi H, Zhang P, Hemmert A, Sun R, Nelson RD. P2Y2 receptor mRNA and protein expression is altered in inner medullas of hydrated and dehydrated rat: relevance to AVP-independent regulation of IMCD function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F1164–F1172, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishore BK, Krane CM, Reif M, Menon AG. Molecular physiology of urinary concentration defect in elderly population. Int Urol Nephrol 33: 235–248, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotnik P Altered expression of COX-1, COX-2, and mPEGS in rats with nephrogenic and central diabetes insipidus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F1053–F1068, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon TW, Laursen UH, Marples D, Maunsbach AB, Knepper MA, Frøkiær J, Nielsen S. Altered expression of renal AQPs and Na+ transporters in rats with lithium-induced NDI. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F552–F564, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leipziger J Control of epithelial transport via luminal P2 receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F419–F432, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenox RH, McNamara RK, Papke RL, Manji HK. Neurobiology of lithium. J Clin Psychiatry 58: 37–47, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luckey AE, Parsa CJ. Fluid and electrolytes in the aged. Arch Surg 138:1055–1060, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manji HK, Moore GJ, Chen G. Lithium at 50: have the neuroprotective effects of this unique cation been overlooked? Biol Psychiatry 46: 929–940, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marples D, Christensen S, Christensen EI, Ottosen PD, Nielsen S. Lithium-induced downregulation of aquaporin-2 water channel expression in rat kidney medulla. J Clin Invest 95: 1935–1845, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer MC, Rastogi P, Beckett CS, McHowat J. Phospholipase A2 inhibitors as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Curr Pharm Des 11: 1301–1312, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell PB, Malhi GS. Emerging drugs for bipolar disorders. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 11: 621–634, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray MD, Brater DC. Renal toxicity of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 32: 435–465, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadler SP, Zimplemann JA, Hebert RL. PGE2 inhibits water permeability at a post-cAMP site in rat terminal inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 262: F229–F235, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phelan KM, Mosholder AD, Lu S. Lithium interaction with the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors rofecoxib and celecoxib and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 1328–1334, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao R, Zhang MZ, Zhao M, Cai H, Harris RC, Breyer MD, Hao CM. Lithium treatment inhibits renal GSK-3 activity and promotes cyclooxygenase 2-dependent polyuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F642–F649, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roman RJ, Lechene C. Prostaglandin E2 and F2α reduced urea absorption from the rat collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 241: F53–F60, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rouch AJ, Kudo LH. Role of PGE2 in α2-induced inhibition of AVP- and cAMP-stimulated H2O, Na+, and urea transport in rat inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F294–F301, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowe MK, Chuang DM. Lithium neuroprotection: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Expert Rev Mol Med 18: 1–18, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwiebert EM ATP release mechanisms, ATP receptors and purinergic signaling along the nephron. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 28: 340–350, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwiebert EM, Kishore BK. Extracellular nucleotide signaling along the renal epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F945–F963, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sugawara M, Hashimot K, Ota Z. Involvement of prostaglandin E2, cAMP, and vasopressin in lithium-induced polyuria. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 254: R863–R869, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun R, Carlson NG, Hemmert AC, Kishore BK. P2Y2 receptor-mediated release of prostaglandin E2 by medullary collecting duct is altered in hydrated and dehydrated rats: relevance to AVP-independent regulation of IMCD function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F585–F592, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun R, Miller RL, Hemmert AC, Zhang P, Shi H, Nelson RD, Kishore BK. Chronic dDAVP infusion in rats decreases the expression of P2Y2 receptor in inner medulla and P2Y2 receptor-mediated PGE2 by IMCD. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F769–F776, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun R, Nelson RD, Carlson NG, Miller RL, Shi H, Zhang P, Hemmert AC, Kohan DE, Kishore BK. Enhanced purinergic-mediated PGE2 release from the medullary collecting duct of rats with acquired nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Pathophysiological and therapeutic implications (Abstract). FASEB J 19: A58, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallon V P2 receptors in the regulation of renal transport mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F10–F27, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wada A, Yokoo H, Yanagita T, Kobayashi H. Lithium: potential therapeutics against acute brain injuries and chronic neurodegenerative diseases. J Pharmacol Sci 99: 307–321, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welch BD, Carlson NG, Shi H, Myatt L, Kishore BK. P2Y2 receptor-stimulated release of prostaglandin E2 by rat inner medullary collecting duct preparations. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F711–F721, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wildman SSP, Marks J, Turner CM, Yew-Booth L, Peppiate-Wildman CM, King BF, Shirley DG, Wang W, Unwin RJ. Sodium-dependent regulation of amiloride sensitive currents by apical P2 receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 731–742, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zelenina M, Christensen BM, Palmer J, Narin AC, Nielsen S, Aperia A. Prostaglandin E2 interaction with AVP: effect of AQP2 phosphorylation and distribution. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F338–F394, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Sands JM, Kohan DE, Nelson RD, Martin CF, Carlson NG, Kamerath CD, Ge Y, Klein JD, Kishore BK. Potential role of purinergic signaling in urinary concentration in inner medulla: insights from P2Y2 receptor gene knockout mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1715–F1724, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]