Abstract

Rat cardiac fibroblasts (CF) express multiple adenosine (ADO) receptors. Pharmacological evidence suggests that activation of A2 receptors may inhibit collagen synthesis via adenylyl cyclase-induced elevation of cellular cAMP. We have characterized the signaling pathways involved in ADO-mediated inhibition of collagen synthesis in primary cultures of adult rat CF. ANG II stimulates collagen production in these cells. Coincubation with agents that elevate cellular cAMP [the ADO agonist, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadensoine (NECA), and forskolin] inhibited the stimulatory effects of ANG II. However, direct stimulators and inhibitors of protein kinase A (PKA) did not alter ANG II-induced collagen synthesis, indicating that PKA does not mediate the inhibitory effects of NECA. Inhibitors of AMP-kinase (AMPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) do not alter NECA-inhibited collagen synthesis. However, activation of exchange factor directly activated by cAMP (Epac) mimicked the effects of NECA on ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis. Inhibition of phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) reduced the inhibitory effects of NECA on ANG II-induced collagen synthesis, suggesting that NECA acts via PI3K. Furthermore, inhibition of PI3K also relieved the inhibitory effect of Epac activation on ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis. Thus it appears that ADO activates the A2R-Gs-adenylyl cyclase pathway and that the resultant cAMP reduces collagen synthesis via a PKA-independent, Epac-dependent pathway that feeds through PI3K.

Keywords: A2 receptors, Epac, phosphoinositol-3 kinase, cardiac collagen deposition

cardiac fibroblasts (CF) synthesize and secrete components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), a complex network of connective tissue proteins that surrounds and interconnects cardiac cells (25, 27). Main components of the cardiac ECM are fibrillar collagens type I and III (27). Under normal physiological conditions, the ECM preserves cardiac structure and function by maintaining the shapes of cells, transmitting mechanical/contractile forces from individual myocytes for coordinated contractions, and regulating elastic recoil during cavity filling (diastole) and contraction (systole) (11, 22). In pathological conditions such as those seen with hypertension and heart failure, excessive deposition of collagen occurs throughout the myocardium (i.e., interstitial fibrosis). Excess fibrosis can lead to interruption of cell-cell connections and prevent coordinated contractions of the whole heart. The excess fibrosis also enhances tissue stiffness, which leads to impaired diastolic and systolic functions (5, 14, 15, 27). Several growth factors have been identified as promoters of the excess deposition of cardiac collagens (3). Experimental and clinical studies support a prominent role for ANG II in promoting the excess deposition of cardiac ECM proteins with disease (2, 25, 30). Current therapies aim to block the action of ANG II as a means to reduce cardiac fibrosis. However, the identification of agents that may have direct anti-fibrotic actions is of great interest.

Adenosine (ADO) reportedly inhibits multiple CF functions including cell proliferation, protein, and collagen synthesis (6, 8–10). Pharmacological data, including our own (see Ref. 10a), indicate that the effects are likely mediated by receptors of the A2 subclass. Stimulation of A2 receptors on adult rat CF leads to the elevation of cAMP and to antiproliferative and antifibrotic effects. In vivo studies using a rat model of myocardial infarction indicate that agents that increase endogenous ADO levels can, indeed, reduce scar tissue deposition (24). Presumably, the inhibitory actions of ADO on fibroblast collagen production occur via elevation of cAMP, a supposition supported by the ability of forskolin (FSK) to inhibit serum-stimulated collagen synthesis (10a). Canonical pathways associated with downstream actions of ADO-induced increases in intracellular cAMP levels include the activation of protein kinase A (PKA), activation of cAMP response element, and activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) (23).

The objectives of this study were to identify mechanisms by which activation of A2 receptors results in inhibition of collagen synthesis in cultured rat CF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ANG II was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 8-Bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphothioate (Rp isomer) (Rp-8-Br-cAMPS), Sp-8-Br-cAMPS (Sp isomer), and 8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (CPT) were obtained from Alexis Biochemicals. Compound C was purchased from EMD-Biosciences Calbiochem. l-[2,3,4,5-3H]proline was purchased from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences. All other reagents used for the stated experiments were obtained as described in the related manuscript.

CF isolation and culture.

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UCSD, which is accredited by AAALAC. Primary adult rat CF cultures were generated from ventricular tissues of 6- to 8-wk-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–275 g) as previously described (see Ref. 10a).

Measurement of [3H]proline incorporation into collagen protein.

To measure collagen synthesis, CF were incubated with 1 μCi/ml [3H]proline, and at the desired times extracellular proline was removed by aspiration of media, plates were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 1 ml of 5% cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to solubilize intracellular free [3H]proline and precipitate [3H]proline incorporated into collagen. After 10 min, TCA was aspirated, and 0.4 N NaOH was added to solubilize the precipitated proteins. A portion was reserved for determination of total protein concentration by the method of Bradford; the remainder was added to scintillation vials to determine [3H]proline incorporated into protein (largely collagen). Nonspecific incorporation of [3H]proline was defined as that adhering to cells in the presence of an excess of unlabeled proline (10 mM); this value was used as a background and subtracted from experimental values obtained from the TCA supernatants.

CF treatment and characterization of optimal assay conditions.

CF were grown to the desired confluency (∼70%) in six-well plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and rendered quiescent by serum starvation (2 h). Prior studies have used incubation times ranging from 48 to 72 h in assessing effects of growth factors on [3H]proline incorporation into precipitable protein (collagen). However, long incubation times in the presence of serum can complicate the interpretation of results since significant cell growth takes place, dedifferentiaon may become evident, and cell death may occur. Studies were conducted to determine whether a shorter incubation protocol without serum could preserve cell viability (assessed by trypan blue exclusion and maintenance of cell morphology and cell number) and provide measurable hormonal effects on incorporation of [3H]proline into precipitable protein. Results indicate that 2 h of serum starvation and 14 h in the presence of [3H]proline ± pharmacological agents provide a treatment paradigm that meets these criteria; this protocol was used in the experiments reported below, unless otherwise noted. Antagonists were added 20 min before the addition of agonists in pharmacological experiments. Cell proliferation (total cell number) was not altered by ANG II or NECA (data not shown). Treatment (14 h) with ANG II increased total protein levels by only ∼12%, ANG II + NECA by 11%.

ERK 1/2 and Akt activation.

After agonist stimulation, experiments were stopped by aspiration of media, a single rinse with PBS, and the addition of cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethlysulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 mM NaF, 30 mM β-glycerolphosphate, pH 7.0). Equal amounts of total protein were processed by SDS-PAGE. Phospho-ERK1/2, total ERK1/2, phospho-Akt, or total Akt were detected on Western blots by immunochemiluminescence (NEB Cell Signaling Technology and Amersham Life Sciences).

Analysis of data.

All data were graphed and analyzed using Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All data are reported as means ± SE. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Student's paired t-test, Student's unpaired t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison posttest, or two-way ANOVA. Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

ADO effects on ANG II-induced collagen synthesis.

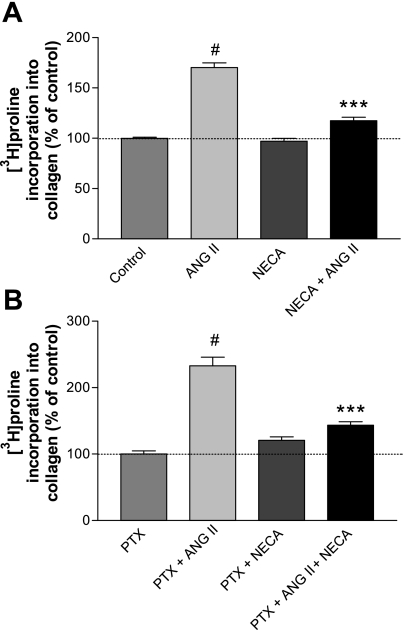

Stimulation of CF with 100 nM ANG II significantly increased incorporation by [3H]proline into protein by ∼70% (Fig. 1A). Cotreatment with 10 μM NECA inhibited the stimulatory effect of ANG II. To determine whether increases in proline incorporation were dependent on protein synthesis, cells were treated for 20 min with cycloheximide (20 μM, added 20 min before addition of [3H]proline and ANG II). Pretreatment with cycloheximide inhibited all responses [proline incorporation as function of control (5,400 ± 190 cpm = 1.0): ANG II (100 nM), 1.6; NECA (10 μM), 0.9; ANG II ± NECA, 1.1; in presence of cycloheximide, 0.1 for all conditions; mean ± SE = 0.2, n = 8]. Thus incorporation of [3H]proline into TCA-precipitable counts is dependent on protein synthesis. Stimulation of collagen synthesis by ANG II and inhibition of the ANG II effect by NECA were verified by the use of a immunoassay that detects rat procollagen type I fragments (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

A: 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadensoine (NECA) significantly inhibits the ANG II-mediated increase in [3H]proline incorporation. Cardiac fibroblast(s) (CF) were labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 10 μM NECA, or both for 14 h (n ≥ 40; #P < 0.001 vs. control; ***P < 0.001 vs. ANG II). B: NECA effects are insensitive to pertussis toxin (PTX) pretreatment. CF were pretreated with PTX (0.1 μg/ml) for 16 h and then labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 10 μM NECA, or both for 14 h. Pretreatment with PTX did not relieve the inhibition by NECA (n = 6; #P < 0.001 vs. PTX; ***P < 0.001 vs. PTX + ANG II).

Gi/o-coupled signaling and ADO-mediated regulation of collagen synthesis.

In the related paper (10a), we identified the presence of a functional adenosine receptors (AR) in CF that signals via Gi/o. The influence of Gi/o on cellular cAMP content is minor, but ADO agonists do modulate the cAMP pathway via Gi/o. Thus it seemed possible that an effect of ADO on collagen synthesis may be partly mediated via Gi/o. To examine this possibility, CF were treated with pertussis toxin (PTX) for 16 h and then treated for 14 h with 100 nM ANG II ± 10 μM NECA. Treatment with PTX did not alter the inhibitory effect of NECA on ANG II-mediated collagen synthesis (Fig. 1B), even though it abolished the capacity of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) to stimulate ERK1/2 phosphorylation (ERK1/2 phosphorylation as function of control = 1: PTX, 0.2; LPA [10 μM for 5 min], 8.5; PTX ± LPA, 1.0). Thus a role for the A1R or A3R and Gi/o-coupled signaling in the ADO-mediated regulation of collagen synthesis appears unlikely.

cAMP, PKA, and ADO-mediated regulation of collagen synthesis.

FSK, a direct activator of adenylyl cyclase (AC), mimicked ADO-mediated inhibition of ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis (Fig. 2A). To determine the role of PKA activation in ADO-inhibited collagen synthesis, we employed the specific PKA activator Sp-8-Br-cAMPS. Treatment of CF with 30 μM Sp-8-Br-cAMPS did not inhibit ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis (Fig. 2B). The same concentration of Sp-8-Br-cAMP did, however, cause phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3-β (GSK-3β) at Ser9, a known substrate of PKA (16), indicating that Sp-8-Br-cAMP does activate PKA in CF (increase in phosphorylation over control, 25 ± 6%, n = 14, P < 0.05, after 30 min treatment with Sp-8-Br-cAMP at 30 mM). The inability of Sp-8-Br-cAMPS to mimic ADO suggested that activation of PKA by cAMP is not involved in the mechanism by which ADO inhibits ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis.

Fig. 2.

A: forskolin (FSK) inhibits ANG II-mediated increases in [3H]proline incorporation. CF were labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 10 μM FSK, or both for 14 h (n ≥ 6; #P < 0.001 vs. control; ***P < 0.001 vs. ANG II). B: 8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphothioate, Sp-isomer (Sp-8-Br-cAMPS) had no effect on the ANG II-mediated increase in [3H]proline incorporation. CF were labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 30 μM Sp-8-Br-cAMPS, or both for 14 h (n = 6; #P < 0.001 vs. control). C and D: protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitors do not relieve NECA-stimulated inhibition of the ANG II-mediated increase in [3H]proline incorporation. CF were pretreated with 10 μM H89 (C) or 100 μM Rp-8-Br-cAMPS (RP) (D) for 20 min and then concurrently labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 10 μM NECA, or both for 14 h (n = 6; #P < 0.001 vs. Rp-8Br-cAMPS. $P < 0.05 vs. H89; ***P < 0.001 vs. RP + ANG II; *P < 0.05 vs. H89 + ANG II).

To confirm the lack of involvement of PKA, we performed experiments employing the PKA inhibitors N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinoline sulfonamide (H89) and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS. Neither H89 nor Rp-8-Br-cAMPS reversed the effect of NECA to inhibit ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis (Fig. 2, C and D). Control experiments demonstrated that these concentrations of H89 and Rp-8-Br-cAMPS significantly inhibit the phosphorylation of GSK-3β that occurs in response to the elevation of cAMP that accompanies exposure to FSK (10 μM for 15 min). Thus we concluded that the effect of ADO agonists to inhibit collagen synthesis involves cAMP but is PKA independent.

ADO, AMPK, cAMP-Epac-PI3K, and collagen synthesis.

We investigated the possible involvement of two pathways downstream from AR-induced cAMP synthesis, adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK) and exchange factor directly activated by cAMP (Epac). Cellular phosphodiesterase(s) (PDEs) are known to convert cAMP to AMP, which in turn can activate AMPK (4). In CF, AMP production from this pathway can be significant (12). cAMP can also directly activate Epac, a guanine exchange factor for the small GTPases repressor activator proteins-1 (Rap1) and -2 (Rap2) (7). Common downstream mediators of Epac and Rap include phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) and ERK1/2; ERK1/2 is activated by ADO likely downstream of cAMP (see Ref. 10a).

To assess the involvement of AMPK, CF were pretreated with 5 μM compound C, an AMPK inhibitor, for 20 min, followed by treatment with 100 nM ANG II ± 100 μM NECA for 14 h to assess [3H]proline incorporation. Pretreatment with compound C did not relieve the inhibition by NECA of ANG II-induced proline incorporation into protein (data not shown), suggesting that AMPK is not involved in mediating the effects of NECA. The involvement of Epac was evaluated by using the specific activator CPT. CPT significantly inhibited proline incorporation induced by 100 nM ANG II (Fig. 3A). GSK-3β phosphorylation, used as a surrogate for PKA activation, was not increased by CPT treatment; in fact, CPT reduced basal levels of GSK-3β phosphorylation (to 80 ± 3% of control, n = 14, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

A: Epac activator 8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (CPT) inhibits the ANG II-mediated increase in [3H]proline incorporation in CF. CF were labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 100 μM CPT, or both for 14 h (n ≥ 6; #P < 0.001 vs. control; ***P < 0.01 vs. ANG II). B: CPT increases CF extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner. CF were treated with 100 μM CPT for the times indicated (mean ± range; n = 2; *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.01 vs. control; ***P < 0.001 vs. control).

As a further test of the specificity of CPT, we assessed its effect on ERK1/2, which is activated by ADO agonists. CPT promoted phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). A concentration of H89 that inhibited GSK3-β phosphorylation by PKA did not block the ability of CPT to activate ERK1/2 (data not shown). These data suggest that ERK1/2 activation by ADO agonists reflects a cAMP-dependent, PKA-independent event that occurs through Epac and that the effect of ADO agonists to inhibit ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis occurs via a cAMP-Epac pathway.

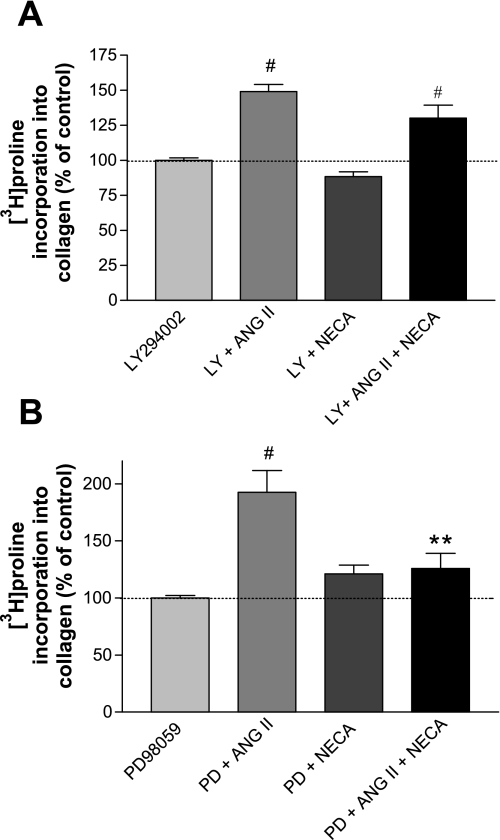

Two pharmacological agents were used to determine whether the effects of ADO on ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis involve ERK1/2 or PI3K: LY-294002 (LY), an inhibitor of PI3K, and PD-98059 (PD), an inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK), the protein kinase that phosphorylates ERK1/2. Treatment with LY relieved the inhibitory effect of NECA on ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis (Fig. 4A); treatment with PD did not alter the effects of NECA (Fig. 4B). To verify that PD actually inhibited ERK1/2 activation under these conditions, we assessed the capacity of PD to inhibit LPA-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. LPA significantly increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation (see above) and pretreatment with PD reduced this increase to control levels. Thus the activation of PI3K, but not of MEK or ERK1/2, appears involved in NECA-mediated inhibition of ANG II-stimulated collagen synthesis.

Fig. 4.

A: inhibition of phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) relieves the NECA-stimulated inhibition of the ANG II-mediated increase in [3H]proline incorporation. CF were pretreated with 10 μM LY-294002 (LY) for 20 min and then concurrently labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 10 μM NECA, or both for 14 h. In the presence of LY, ANG II increased [3H]proline incorporation in the presence or absence of NECA; i.e., LY relieved the inhibitory effect of NECA (n = 6; #P < 0.001 vs. corresponding control). B: inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) (ERK1/2) does not relieve NECA-stimulated inhibition of the ANG II-mediated increase in [3H]proline incorporation. CF were pretreated with 10 μM PD-98059 (PD) for 20 min and then labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 10 μM NECA, or both for 14 h (n = 6; #P < 0.001 vs. PD-98059, **P < 0.01 vs. PD + ANG II).

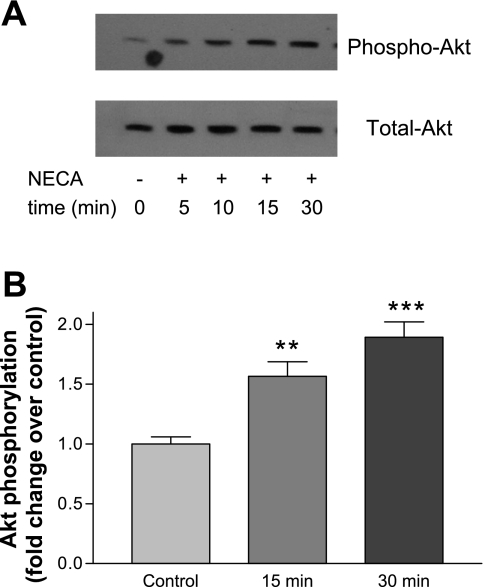

These data suggest that PI3K may be activated as a consequence of Epac activation and that inhibition of collagen synthesis occurs downstream of Epac via PI3K. Other data support this possibility: blockade of PI3K activity with LY relieved the inhibitory effect of Epac activation (in response to CPT treatment) on ANG II-stimulated proline incorporation into protein (Fig. 5). Treatment of cells with NECA also caused the time-dependent phosphorylation of protein kinase B (PKB) (AKT) (Fig. 6), an effect that LY, the PI3K inhibitor, significantly inhibited (AKT phosphorylation as fold over control = 1: NECA, 1.7 ± 0.2; NECA + LY, 1.0 ± 0.2, P < 0.01 for effects of NECA and LY). This suggests that NECA activates PKB via PI3K activation, and that ADO agonists can act via PKB to downregulate ANG II-induced collagen synthesis.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of PI3K relieves the CPT-stimulated inhibition of the ANG II-mediated increase in [3H]proline incorporation. CF were pretreated with 10 μM LY for 20 min and then labeled with [3H]proline and treated with 100 nM ANG II, 100 μM CPT, or both for 14 h (n = 6; #P < 0.001 for effects of ANG II vs. corresponding control).

Fig. 6.

NECA increases AKT (protein kinase B, PKB) phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner. CF were treated with 10 μM NECA for the times indicated. A: representative phospho- and total-Akt immunoblots. B: quantitation of AKT phosphorylation at 15- and 30-min time points (n ≥ 10; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

We have developed an experimental paradigm that avoids some of the problems generally encountered in studies of collagen synthesis by cultured fibroblasts. Most in vitro models of cardiac fibrosis assess changes in collagen synthesis via [3H]proline incorporation, and the majority of these studies use fetal bovine serum as the stimulus to increase collagen synthesis (8). Although serum is an excellent stimulus for cell growth and collagen synthesis, it is inherently complex and contains many growth factors, including LPA, angiotensin, and catecholamines. We have developed a serum-free protocol in which these confounding factors are removed. Second, we have employed ANG II as the “profibrotic” stimulus. The role that ANG II plays in modulating pathological cardiac remodeling and fibrosis is supported by extensive studies performed in vitro, in vivo, and by clinical trials (2, 25, 30). In this study, we utilized ANG II treatment of isolated CF as the means to stimulate incorporation of proline into collagen to examine the signaling mechanisms by which ADO may counteract its effects. The protocol that we have developed provides useful data within 14 h, thereby avoiding issues of long-term cell growth encountered in traditional protocols (48–72 h).

In cultured rat CF, ADO inhibits functions known to be associated with fibrosis. Both exogenous and endogenous ADO decrease serum-induced proliferation measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation, protein synthesis measured by l-[3H]leucine incorporation, and collagen synthesis measured by l-[3H]proline incorporation (8, 9, 24). Available evidence suggests that inhibition of most, if not all, of these functions by ADO occurs via A2Rs (6, 8, 9). Indeed, the data in our accompanying paper (10a) firmly support this conjecture. Although most workers agree that the effects of ADO likely occur via cAMP, the direct pathway by which ADO-stimulated cAMP acts is not known. Activation of PKA is the best-known pathway by which cAMP mediates effects; however, cAMP can interact with other downstream effectors: cyclic nucleotide- gated ion channels (CNGs), Epac, and PDEs. CNGs, while found in nonneuronal cell types, are predominantly located in photoreceptor cells and olfactory sensory neurons (1, 17). Whereas it is not likely that CNGs are functioning in CF, Epac is present. Epac, functions as a guanine exchange factor for the small GTPases Rap1 and Rap2 (7). Activation of Rap by Epac can lead to further signaling and activation of pathways involving ERK1/2 or PI3K (26,28). Indeed, overexpression of Epac in the heart inhibits collagen synthesis stimulated by transforming growth factor-β (29). Additionally, an elevation in cAMP by ADO could conceivably lead to downstream activation of AMPK, since degradation of cAMP by PDEs in CF is robust and could produce sufficient 5′-AMP when the Gs-AC pathway is modestly stimulated (12). AMPK functions to decrease anabolic pathways such as protein synthesis (13, 18). Thus the examination of mechanisms of ADO-mediated decreases in collagen synthesis with ADO also required assessing the involvement of downstream effects of Epac and AMPK. There is precedent for these possibilities. In lung fibroblasts the stimulation of the cells with agents that elevate cAMP led to the inhibition of collagen synthesis (19) and proliferation (21), and the anti-proliferative effects were mediated by Epac rather than the classical PKA pathway. Interestingly, inhibitory effects of cAMP on collagen I gene expression appeared not mediated by Epac but by alternate pathways.

We found that stimulation of AMPK with CPT increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CFs in accord with previous data that cAMP elevating agents (e.g., CADO, NECA, FSK, and 8-Br-cAMP) all increase ERK1/2 phosphorylation in these cells. Taken together, this indicates that A2R, via elevation of cAMP, can activate Epac, leading to ERK1/2 activation in CFs. Although NECA and CPT both activated ERK1/2, inhibition of MEK1/2 (the upstream kinase that phosphorylates ERK1/2) with PD-98059 had no effect on relieving the NECA-mediated inhibition of ANG II-induced [3H]proline incorporation. Although ERK1/2 is activated by this ADO-cAMP-Epac signaling pathway, this pathway appears to play no role in the ADO-mediated inhibition of collagen production. However, ERK1/2 activation by cAMP/Epac and by a multiplicity of signals acting through PKC and Ca2+ appears to mediate some of the proliferative responses to ANG II in CF (20).

Our experiments verify the involvement of cAMP in mediating the inhibition of CF collagen synthesis by ADO: FSK mimics the effect of NECA on [3H]proline incorporation. However, the inability of PKA activation (by Sp-8-Br-CAMPS) to inhibit ANG II-induced [3H]proline incorporation and the lack of effect of PKA inhibitors (H89 or Rp-8-Br-cAMPS) on the actions of NECA indicate that the inhibitory effects of NECA do not occur via activation of PKA. Likewise, the lack of effect of inhibitors of AMPK and ERK1/2 on NECA-inhibited [3H]proline incorporation indicates that NECA is not working to inhibit collagen levels via either of these enzymes. Since activation of Epac (by 8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) mimics the effects of NECA on ANG II-stimulated [3H]proline incorporation, we predict that one major inhibitory mechanism by which NECA regulates collagen synthesis is due to Epac activation. However, further verification of the role of Epac by other means (such as gene silencing techniques to reduce cellular Epac1 and/or Epac2) is warranted, so as to verify independently whether the effects of adenosine agonists on collagen synthesis are dependent on Epac activity as the pharmacological data suggest. The ability of PI3K inhibition to relieve the inhibition of NECA on ANG II-induced [3H]proline incorporation also indicates that NECA exerts its inhibitory effects on collagen levels through a pathway that involves PI3K activation. This is supported by the finding that PI3K inhibition also relieves the inhibition of CPT on ANG II-mediated increases in [3H]proline incorporation. Pharmacological data suggest the involvement of PKB downstream from PI3K. Thus a new hypothesis for the mechanism of ADO-mediated inhibition of collagen production is emerging (see Fig. 7) : ADO activates A2Rs leading to an accumulation of intracellular cAMP that activates Epac and PI3K, and possibly PKB, which in turn leads to a decrease in total collagen protein levels; growth control may occur via ERK1/2 (20).

Fig. 7.

Proposed signaling pathway for adenosine-mediated inhibition of collagen production. See text for more information.

The definition of this pathway provides the framework for new points at which to pharmacologically regulate collagen synthesis. In particular, in the setting of postinfarction cardiac remodeling, knowledge of this pathway may permit manipulation of collagen synthesis so that wound healing (scarring) occurs but collagen deposition does not progress to excessive levels.

GRANTS

We acknowledge the support of the following National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants: HL-43617 and HL-67922 to F. Villarreal; NIH-07444 to S. Epperson and GM-68524 to L. Brunton.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradley J, Reisert J, Frings S. Regulation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 343–349, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brilla CG, Rupp H, Funck R, Maisch B. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and myocardial collagen matrix remodelling in congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J 16, Suppl O: 107–109, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. The cardiac fibroblast: therapeutic target in myocardial remodeling and failure. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 45: 657–687, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carling D, Clarke PR, Zammit VA, Hardie DG. Purification and characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase. Copurification of acetyl-CoA carboxylase kinase and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase kinase activities. Eur J Biochem 186: 129–136, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll EP, Janicki JS, Pick R, Weber KT. Myocardial stiffness and reparative fibrosis following coronary embolisation in the rat. Cardiovasc Res 23: 655–661, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Epperson S, Makhsudova L, Ito B, Suarez J, Dillmann W, Villarreal F. Functional effects of enhancing or silencing adenosine A2b receptors in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2478–H2486, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 396: 474–477, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Jackson EK. Adenosine inhibits collagen and protein synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts: role of A2B receptors. Hypertension 31: 943–948, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Mi Z, Jackson EK. Exogenous and endogenous adenosine inhibits fetal calf serum-induced growth of rat cardiac fibroblasts: role of A2B receptors. Circulation 96: 2656–2666, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Zacharia LC, Mi Z, Jackson EK. A(2b) receptors mediate the antimitogenic effects of adenosine in cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 37: 716–721, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Epperson SA, Brunton LL, Ramirez-Sanchez I, Villarreal F. Adenosine receptors and second messanger signaling pathways in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol (February 25, 2009). doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00290.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Factor SM, Robinson TF. Comparative connective tissue structure-function relationships in biologic pumps. Lab Invest 58: 150–156, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustafsson AB, Brunton LL. Attenuation of cAMP accumulation in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts by IL-1beta and NO: role of cGMP-stimulated PDE2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C463–C471, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardie DG, Scott JW, Pan DA, Hudson ER. Management of cellular energy by the AMP-activated protein kinase system. FEBS Lett 546: 113–120, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalil JE, Doering CW, Janicki JS, Pick R, Clark WA, Abrahams C, Weber Structural vs KT. Contractile protein remodeling and myocardial stiffness in hypertrophied rat left ventricle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 20: 1179–1187, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jalil JE, Doering CW, Janicki JS, Pick R, Shroff SG, Weber KT. Fibrillar collagen and myocardial stiffness in the intact hypertrophied rat left ventricle. Circ Res 64: 1041–1050, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen J, Brennesvik EO, Lai YC, Shepherd PR. GSK-3beta regulation in skeletal muscles by adrenaline and insulin: evidence that PKA and PKB regulate different pools of GSK-3. Cell Signal 19: 204–210, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev 82: 769–824, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kemp BE, Stapleton D, Campbell DJ, Chen ZP, Murthy S, Walter M, Gupta A, Adams JJ, Katsis F, van Denderen B, Jennings IG, Iseli T, Michell BJ, Witters LA. AMP-activated protein kinase, super metabolic regulator. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 162–168, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Ostrom RS, Insel PA. cAMP-elevating agents and adenylyl cyclase overexpression promote an antifibrotic phenotype in pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C1089–C1099, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson ER, Shamhart PE, Naugle JE, Meszaros JG. Angiotensin II-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation is mediated by protein kinase C delta and intracellular calcium in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 51: 704–711, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Racke K, Haag S, Bahulayan A, Warnken M. Pulmonary fibroblasts, an emerging target for anti-obstructive drugs. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 378: 193–201, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson TF, Cohen-Gould L, Factor SM, Eghbali M, Blumenfeld OO. Structure and function of connective tissue in cardiac muscle: collagen types I and III in endomysial struts and pericellular fibers. Scanning Microsc 2: 1005–1015, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulte G, Fredholm BB. The G(s)-coupled adenosine A(2B) receptor recruits divergent pathways to regulate ERK1/2 and p38. Exp Cell Res 290: 168–176, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villarreal F, Zimmermann S, Makhsudova L, Montag AC, Erion MD, Bullough DA, Ito BR. Modulation of cardiac remodeling by adenosine: in vitro and in vivo effects. Mol Cell Biochem 251: 17–26, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villarreal FJ, Kim NN, Ungab GD, Printz MP, Dillmann WH. Identification of functional angiotensin II receptors on rat cardiac fibroblasts. Circulation 88: 2849–2861, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Liu F, Adamo ML. Cyclic AMP inhibits extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways by inhibiting Rap1. J Biol Chem 276: 37242–37249, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber KT Extracellular matrix remodeling in heart failure: a role for de novo angiotensin II generation. Circulation 96: 4065–4082, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin F, Wang YY, Du JH, Li C, Lu ZZ, Han C, Zhang YY. Noncanonical cAMP pathway and p38 MAPK mediate beta 2-adrenergic receptor-induced IL-6 production in neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40: 384–393, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokoyama U, Patel HH, Lai NC, Aroonsakool N, Roth DM, Insel PA. The cyclic AMP effector Epac integrates pro- and anti-fibrotic signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 6386–6391, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou G, Kandala JC, Tyagi SC, Katwa LC, Weber KT. Effects of angiotensin II and aldosterone on collagen gene expression and protein turnover in cardiac fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem 154: 171–178, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.