Abstract

The plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) plays a major role in restoring Ca2+ to basal levels following transient elevation by neuronal activity. Here we examined the effects of various stimuli that increase [Ca2+]i on PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance from hippocampal neurons. We used indo-1-based microfluorimetry in the presence of cyclopiazonic acid to study the rate of PMCA-mediated recovery of Ca2+ elevated by a brief train of action potentials. [Ca2+]i recovery was described by an exponential decay and the time constant provided an index of PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance. PMCA function was assessed before and for ≥60 min following a 10-min priming stimulus of either 100 μM N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), 0.1 mM Mg2+ (reduced extracellular Mg2+ induces intense excitatory synaptic activity), 30 mM K+, or control buffer. Recovery kinetics slowed progressively following priming with NMDA or 0.1 mM Mg2+; in contrast, Ca2+ clearance initially accelerated and then slowly returned to initial rates following priming with 30 mM K+-induced depolarization. Treatment with 10 μM calpeptin, an inhibitor of the Ca2+ activated protease calpain, prevented the slowing of kinetics observed following treatment with NMDA but had no affect on the recovery kinetics of control cells. Calpeptin also blocked the rapid acceleration of Ca2+ clearance following depolarization. In calpeptin-treated cells, 0.1 mM Mg2+ induced a graded acceleration of Ca2+ clearance. Thus in spite of producing comparable increases in [Ca2+]i, activation of NMDA receptors, depolarization-induced activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and excitatory synaptic activity each uniquely affected Ca2+ clearance kinetics mediated by the PMCA.

INTRODUCTION

The plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) is an integral part of the Ca2+ regulatory system in neurons (Thayer et al. 2002) and plays a prominent role in returning [Ca2+]i to basal levels following moderate stimuli (Benham et al. 1992; Werth et al. 1996). These Ca2+ pumps hydrolyze ATP to enable the translocation of Ca2+ up the steep gradient across the plasma membrane (Carafoli and Brini 2000). PMCA diversity results from the alternative splicing of four primary transcripts (Strehler and Zacharias 2001) to produce various pump isoforms differing in their distribution within the brain (Stauffer et al. 1995), subcellular localization (DeMarco and Strehler 2001), activity (Enyedi et al. 1994), and modulation (Enyedi et al. 1996; Usachev et al. 2002). Plasma membrane Ca2+ pumps regulate a variety of Ca2+ signaling processes including neurotransmitter release (Empson et al. 2007; Zenisek and Matthews 2000) and excitability (Usachev et al. 2002). Changes in PMCA function accompany aging (Murchison and Griffith 1998), free radical damage (Zaidi et al. 2003), and excitotoxicity (Pottorf et al. 2006).

Ca2+ is not only transported by the PMCA but also regulates its activity. The carboxyl terminal of most PMCA isoforms contains an autoinhibitory domain that, in the absence of Ca2+-calmodulin, inhibits Ca2+ pump activity by intramolecular binding to a site near the ATP catalytic site (Enyedi et al. 1991). Calmodulin in the presence of Ca2+ binds to the autoinhibitory domain removing inhibition and thus stimulates Ca2+ pump activity (Carafoli 1994). The PMCA is also modulated by the Ca2+ activated protease calpain. Calpain-mediated cleavage of the carboxyl terminus autoinhibitory domain results in PMCA activation (James et al. 1989). Alternatively, glutamate-induced calpain activation results in loss of PMCA activity possibly due to internalization of the proteolyzed PMCA (Pottorf et al. 2006).

In this report, we describe the effects of various stimuli that elevate [Ca2+]i on PMCA function. We found that PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance was affected in a Ca2+ source specific manner and that calpain activation was a major contributor to PMCA modulation.

METHODS

Cell culture

Rat hippocampal neurons were grown in primary culture as described previously (Wang et al. 1994) with minor modifications. Fetuses were removed on embryonic day 17 from maternal rats, anesthetized with CO2, and killed by decapitation under a protocol approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Hippocampi were dissected and placed in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free HEPES-buffered Hanks’ salt solution (HHSS), pH 7.45. HHSS was composed of the following (in mM): 20.0 HEPES, 137.0 NaCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.4 MgSO4, 0.5 MgCl2, 5.0 KCl, 0.4 KH2PO4, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 3.0 NaHCO3, and 5.6 glucose. Cells were dissociated by trituration through a 5 ml pipette and a series of flame-narrowed Pasteur pipettes. Cells were pelleted and re-suspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) without glutamine, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively). Dissociated cells then were plated at a density of 10,000–15,000 cells/well onto 25-mm-round cover glasses that had been coated with poly-d-lysine (0.1 mg/ml) and washed with H2O. Neurons were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 10% CO2-90% air (pH 7.4) at 37°C, and fed at days 1 and 6 by exchange of 75% of the media with DMEM supplemented with 10% horse serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells used in these experiments were cultured without mitotic inhibitors for a minimum of 10 days and a maximum of 15 days.

Microfluorometric recording of [Ca2+]i

[Ca2+]i was recorded from cultured rat hippocampal neurons using indo-1-based microfluorometry (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985). Cells were loaded with 2 μM indo-1 acetoxymethyl ester (AM) in HHSS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin at 37°C for 30 min. Cells were rinsed in HHSS and the indicator allowed to de-esterify for 10 min prior to starting the experiment. Coverslips with loaded, washed cells were mounted in a flow-through chamber (10-s solution exchange) equipped with platinum electrodes (Thayer et al. 1988). The chamber was mounted on an inverted epi-fluorescence microscope, and cells localized by phase-contrast illumination with a ×70 objective (NA 1.15). Action potentials were evoked by electric field stimulation as described previously (Piser et al. 1994). For high extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o)-induced depolarization, K+ was substituted for Na+ reciprocally. Experiments were performed at room temperature (22°C). The dye was excited at 350 nm (10 nm band-pass), and emission was detected at 405 (20) and 490 (20) nm. Fluorescence was monitored by a pair of photomultiplier tubes (Thorn, EMI, Fairfield, NJ) operating in photon-counting mode. The output signals were then passed through a frequency to voltage converter and digitized using a Digidata 1322a A/D Converter (MDS Analytical Technologies, Toronto, CA). Data were stored and analyzed on a personal computer.

Fluorescence changes were converted to [Ca2+]i by using the formula [Ca2+]i = Kd β (R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R), where R is 405/490 nm fluorescence ratio (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985). The dissociation constant (Kd) for indo-1 was 250 nM and β was the ratio of fluorescence emitted at 490 nm and measured in the absence and presence of Ca2+. Rmin, Rmax, and β were determined by bathing intact cells in 2 μM ionomycin in Ca2+-free buffer (1 mM EGTA) and saturating Ca2+ (5 mM Ca2+). Values for Rmin, Rmax, and β were 0.25, 2.3, and 3.5, respectively. After completion of each experiment, cells were wiped from the microscope field using a cotton-tipped applicator. Background light levels were determined at each wavelength (∼5% of cell counts) and subtracted prior to calculating ratios.

Statistical analysis

The recovery of intracellular calcium to resting levels was quantified by fitting a monoexponential decay function using a nonlinear, least-squares curve fitting algorithm (Origin 6.1 software) (Usachev et al. 2006). Statistical significance was determined by univariate ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test or by Student's t-test as indicated, an acceptable level of significance was α = 0.05 (SPSS 14.0 software).

Reagents

Indo-1, DMEM, fetal bovine serum, and horse serum were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Calpeptin was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), and all other reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

Method to study PMCA recovery kinetics in hippocampal neurons

The clearance of small (<400 nM) increases in [Ca2+]i from the neuronal cytoplasm is primarily accomplished by ATPases that pump Ca2+ across the plasmalemma and into the endoplasmic reticulum (Usachev et al. 2006). We evoked brief trains of action potentials in indo-1AM-loaded hippocampal neurons by electrical field stimulation (40–90 V; 4–8 Hz, 4 s) to elicit a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1). The [Ca2+]i returned to basal levels by a process well fit by a monoexponential equation with a mean time constant (τ) of 2.2 ± 0.6s (n = 27; Fig. 1B). Application of cyclopiazonic acid (5 μM, CPA) to block the sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), produced a transient rise in basal [Ca2+]i and a slowing of the [Ca2+]i recovery kinetics (τ = 4.5 ± 1.8 s, n = 80). We have shown previously that in the presence of CPA, recovery from action potential-induced [Ca2+]i increases of <400 nM is not significantly influenced by mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake or Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Under these conditions, recovery is predominantly mediated by the PMCA (Pottorf et al. 2006).

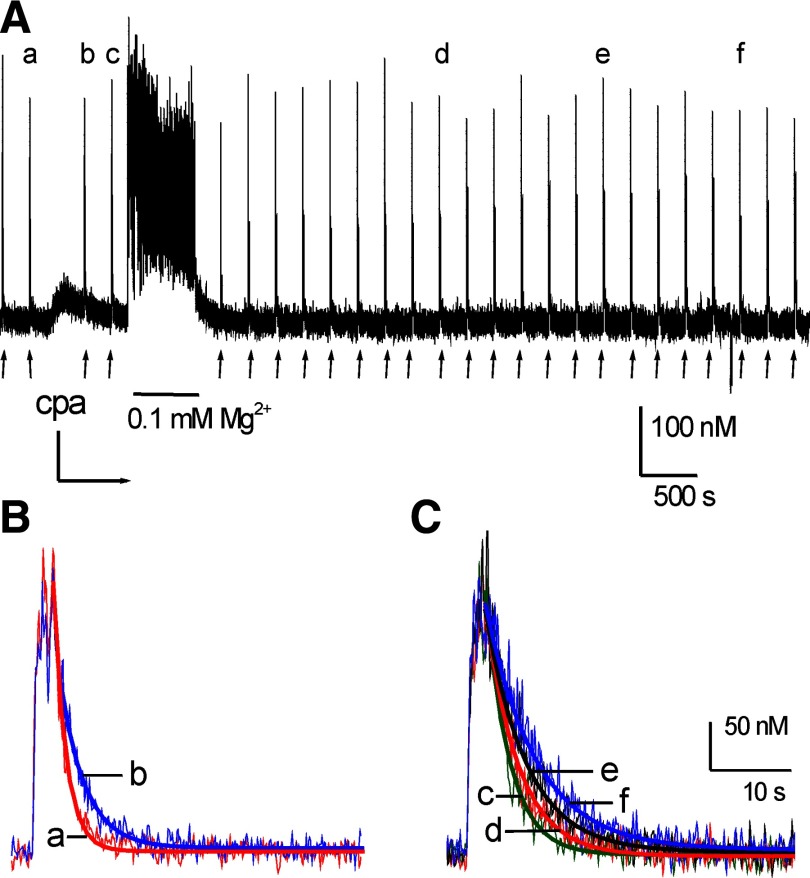

FIG. 1.

Experimental protocol for studying stimulus-induced changes in plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) function in hippocampal neurons. A: representative recording from a hippocampal neuron displays the full protocol used in these experiments. Small, brief increases in [Ca2+]i (test responses) were produced by trains of action potentials elicited by electric field stimulation (↑). Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; 5 μM) was applied at the time indicated and maintained throughout the experiment to block sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA)-type Ca2+ pumps. Recovery of [Ca2+]i from test responses were fit with a monoexponential function and the time constant (τ) calculated. The initial time constant (τ0) was the average of 2 test responses immediately following treatment with CPA (b and c, t = 0 at c). The cell was then treated with a 10-min priming stimulus (starting at t = 2 min), which in this example was a change in [Mg2+]o in the superfusate from 0.9 to 0.1 mM. A test stimulus to assess PMCA function was delivered at 4-min intervals subsequent to return to pretreatment resting levels of [Ca2+]i. B: test responses just before (red; a in A; τ = 1.5 s) and immediately after application of CPA (blue; b in A; τ = 3.0 s) are superimposed on an expanded time scale. Heavy lines are exponential fits to the [Ca2+]i recovery traces. Time 0 is taken as the time of the second test response after CPA treatment (c in A). C: test responses recorded at times 0 (green; c in A; τ = 2.9 s), 48 (red; d in A; τ = 4.0 s), 76 (black; e in A; τ = 5.0 s), and 92 (blue; f A; τ = 6.1 s) min are superimposed on an expanded time scale. Heavy lines are exponential fits to the [Ca2+]i recovery traces.

We used recovery from these small action-potential-induced [Ca2+]i increases as tests of PMCA function in hippocampal neurons and measured τ for at least an hour following challenges with various stimuli. Figure 1 shows an example of this type of experiment. Every 4 min the cell received electrical field stimulation to evoke a brief train of action potentials to elicit a reproducible increase in [Ca2+]i. Initial recovery kinetics (τ0) were defined as the mean of the two τ values calculated for [Ca2+]i transients recorded after the addition of CPA to the superfusate (Fig. 1A, b and c). Two minutes after the second control response (t = 2 min), [Ca2+]i was elevated by applying a test stimulus. For the experiment shown in Fig. 1, the cell was bathed in HHSS in which the extracellular Mg2+ concentration ([Mg2+]o) was reduced from 0.9 to 0.1 mM. Reduced [Mg2+]o induces an epileptic pattern of activity in the synaptic network that forms in hippocampal cultures and is manifest as a series of [Ca2+]i spikes (McLeod et al. 1998). Following a 10-min exposure to 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o, PMCA-mediated recovery kinetics were monitored for over 1 h. The reduced [Mg2+]o initiated a graded slowing of PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i clearance (Fig. 1C).

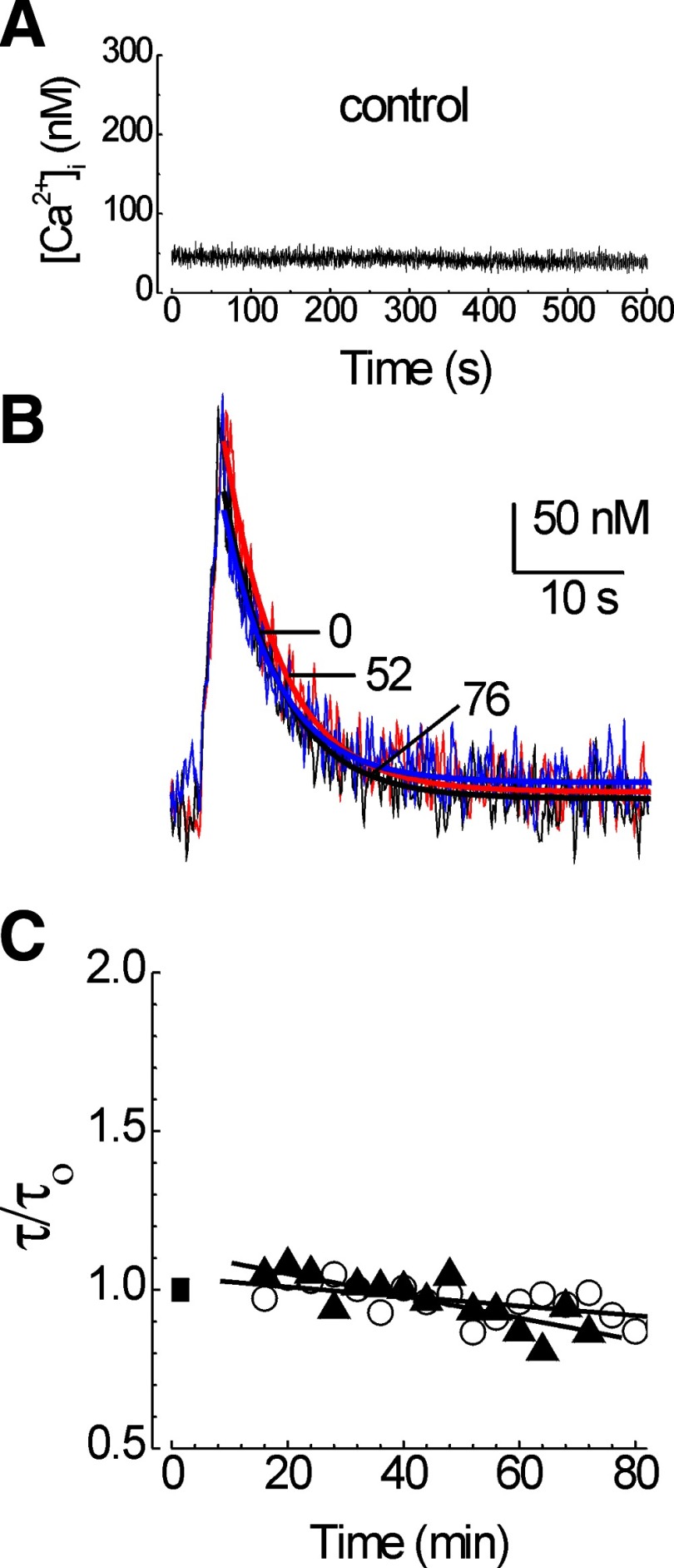

In control recordings, no stimulus was applied during the priming period (Fig. 2A) and thus [Ca2+]i remained at basal levels. PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i recovery kinetics were stable over the time course of these experiments (Fig. 2B). The slight acceleration suggested by the negative slope of a plot of τ/τ0 versus time was not statistically significant (Fig. 2C; n = 5). The Ca2+-activated protease calpain can accelerate or impair PMCA activity depending on conditions (James et al. 1989; Pottorf et al. 2006). However, under control conditions, the calpain inhibitor calpeptin (10 μM) did not affect PMCA function (Fig. 2C; n = 6). Thus in the absence of a priming stimulus, calpain was not activated, and PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i recovery kinetics were stable for the duration of the experiment.

FIG. 2.

PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i recovery kinetics are stable in untreated hippocampal neurons. PMCA function was measured using the protocol presented in Fig. 1. A: in the absence of a priming stimulus, the [Ca2+]i remained at basal levels. B: test responses recorded at times 0 (blue; τ = 5.0 s), 52 (red; τ = 5.1 s), and 76 (black; τ = 5.0 s) min are superimposed on an expanded time scale. C: the time constant for [Ca2+]i recovery (τ) was normalized to the initial time constant (τ/τo) prior to application of the priming stimulus (▪) and plotted vs. time. Plots are from representative cells recorded in the absence (○) and presence (▴) of 10 μM calpeptin.

Stimulus-induced changes in PMCA recovery kinetics

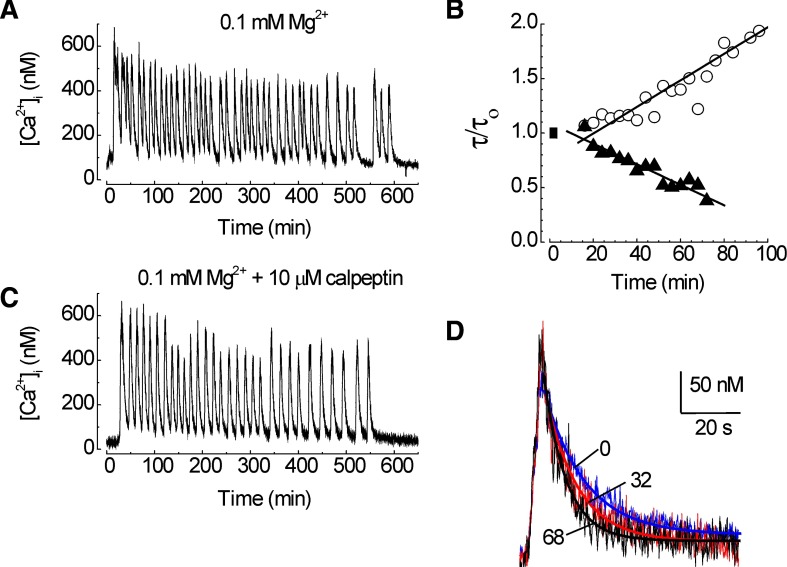

Treating hippocampal neurons with 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o as described in Fig. 1 induced an intense pattern of excitatory synaptic activity that results in a series of [Ca2+]i spikes (Fig. 3A). Reducing [Mg2+]o induces paroxysmal excitatory bursts analogous to epileptic activity (Rose et al. 1990). Following 10-min exposure to 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o, PMCA-mediated recovery kinetics displayed a graded slowing (Figs. 1C and 3B). τ increased at a rate of 0.006 min-1 and was significantly greater than control cells (P < 0.05). In cells treated with calpeptin for ≥20 min prior to the stimulus and throughout the recording, the 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o priming stimulus initiated a graded acceleration of PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i clearance (Fig. 3B). Thus in calpeptin-treated cells, 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o induced an increase in Ca2+ clearance rate of 0.0015 min-1 which was significantly faster than control cells (P < 0.01). Calpeptin did not affect 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o-induced [Ca2+]i spiking activity (Fig. 3C). The number of [Ca2+]i spikes during the 10-min treatment was 45 ± 17 in untreated cells and 36 ± 10 in the presence of calpeptin, and the difference between them was not significant (t7 = −1.36). The mean spike amplitude in untreated and treated cells was 469 ± 216 and 495 ± 218 nM, respectively, and the difference between them was not significant (t325 = 1.1). Thus in the presence of calpeptin, the same [Ca2+]i increase that caused a calpain-mediated slowing of Ca2+ clearance, now produced an acceleration of PMCA activity (Fig. 3, B and D; P < 0.01). The source of Ca2+ during 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o-induced [Ca2+]i spiking is from both voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (McLeod et al. 1998). We next examined the effects of stimulating these channels individually on Ca2+ clearance rate.

FIG. 3.

0.1 mM [Mg2+]o-induced [Ca2+]i spiking evoked calpain-mediated loss of PMCA activity. PMCA function was measured using the protocol presented in Fig. 1. A: a priming stimulus in which the [Mg2+]o in the superfusate was changed from 0.9 to 0.1 mM evoked repetitive [Ca2+]i spikes. Trace is from time 2–12 min from the recording shown in Fig. 1A. B: the time constant for [Ca2+]i recovery (τ) was normalized to the initial time constant (τ/τo) prior to application of the 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o priming stimulus (▪) and plotted vs. time. Plots are from representative cells recorded in the absence (○) and presence (▴) of 10 μM calpeptin. C: calpeptin did not affect 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o-induced [Ca2+]i spiking. D: test responses recorded at times 0 (blue; τ = 11.7 s), 32 (red; τ = 9.2 s), and 68 (black; τ = 5.9 s) min from a cell treated with calpeptin and primed with 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o are superimposed on an expanded time scale. Heavy lines are exponential fits to the data.

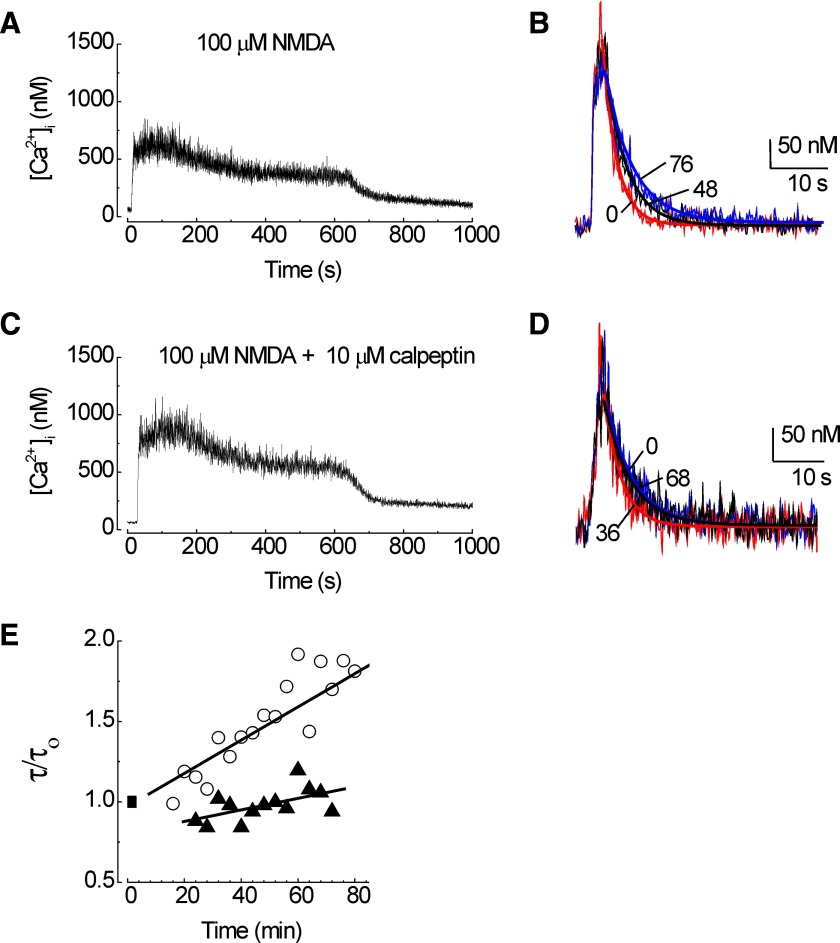

NMDA (100 μM) induced a large [Ca2+]i increase that peaked at 777 ± 208 nM and declined to 337 ± 113 nM by the end of the 10-min priming stimulus (Fig. 4A). This stimulus produced a graded slowing in PMCA-mediated recovery kinetics (Fig. 4, B and E). τ increased at a rate of 0.007 min-1 and was significantly greater than control cells (P < 0.01). In contrast, NMDA did not significantly affect PMCA function in the presence of calpeptin (Fig. 4, D and E). Calpeptin did not affect the NMDA-induced [Ca2+]i increase (Fig. 4C). The [Ca2+]i peaked at 934 ± 160 nM and declined to 466 ± 183 nM by 10 min, similar to responses recorded from untreated cells (t8 = 1.3, 1.4, respectively). Thus 10-min treatment with NMDA induced a calpain-mediated slowing of PMCA activity.

FIG. 4.

N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-evoked calpain-mediated loss of PMCA activity. PMCA function was measured using the protocol presented in Fig. 1. A: an NMDA (100 μM) priming stimulus evoked a large increase in [Ca2+]i. B: test responses recorded at times 0 (red; τ = 2.8), 48 (black; τ = 4.2), and 76 (blue; τ = 5.5) min following priming with 100 μM NMDA are superimposed on an expanded time scale. Heavy lines are exponential fits to the data. C: calpeptin did not affect the NMDA-induced [Ca2+]i increase. D: test responses recorded at times 0 (black; τ = 5.3 s), 36 (red; τ = 3.3 s), and 68 (blue; τ = 5.2 s) minutes from a cell treated with calpeptin and primed with 100 μM NMDA are superimposed on an expanded time scale. E: the time constant for [Ca2+]i recovery (τ) was normalized to the initial time constant (τ/τo) prior to application of the NMDA priming stimulus (▪) and plotted vs. time. Plots are from representative cells recorded in the absence (○) and presence (▴) of 10 μM calpeptin.

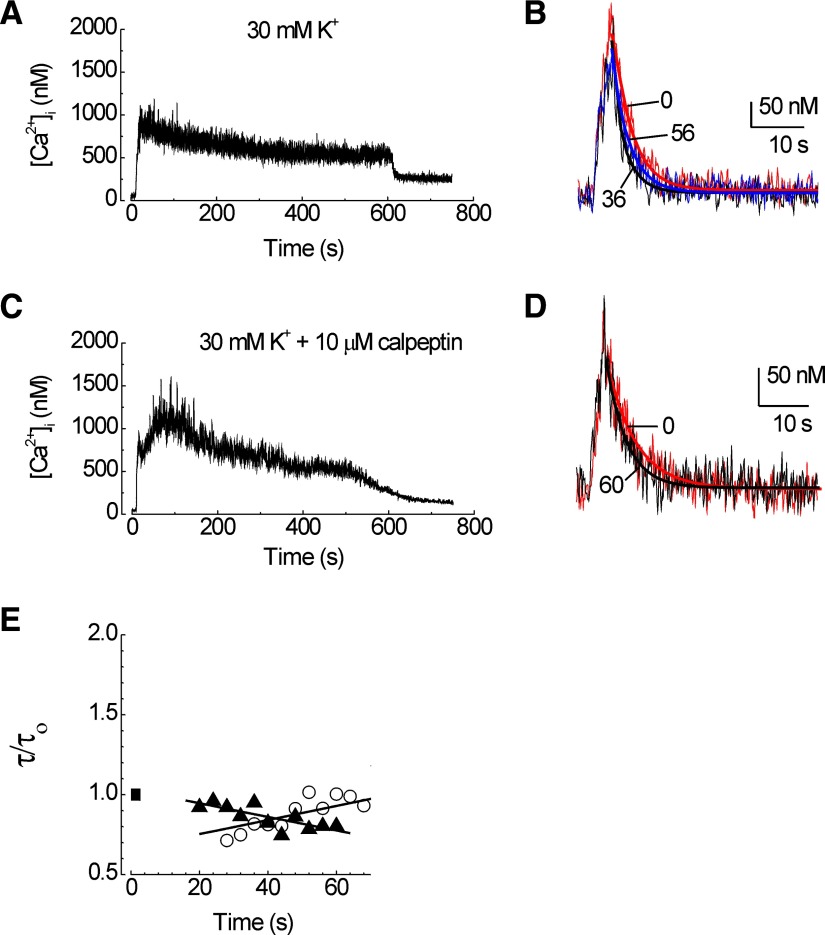

Activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) by elevating the extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o) to 30 mM produced a sustained elevation in [Ca2+]i that peaked at 1463 ± 532 nM (Fig. 5A). In contrast to the other stimuli examined here, activation of VGCCs produced a rapid acceleration of Ca2+ clearance that gradually returned to the original rate (Fig. 5, B and E). The y intercept extrapolated from the data in Fig. 5E was 0.5, and the recovery time constant (τ/τo) increased at a rate of 0.005 min-1. In the presence of calpeptin (10 μM), the 30 mM [K+]o stimulus did not significantly affect recovery kinetics, although an accelerating trend in PMCA activity was apparent (Fig. 5E). Calpeptin did not significantly affect the depolarization-induced [Ca2+]i increase (peak [Ca2+]i = 1658 ± 427 nM; t9 = 0.66; Fig. 5C). Thus depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx produced an initial calpain-dependent acceleration of Ca2+ clearance that gradually returned to the initial rate.

FIG. 5.

Depolarization-induced calpain-mediated modulation of PMCA activity. PMCA function was measured using the protocol presented in Fig. 1. A: a depolarizing priming stimulus of 30 mM [K+]o evoked a large increase in [Ca2+]i. B: test responses recorded at times 0 (red; τ = 3.4 s), 36 (black; τ = 2.7 s), and 56 (blue; τ = 3.0 s) minutes following priming with 30 mM [K+]o are superimposed on an expanded time scale. Heavy lines are exponential fits to the data. C: calpeptin did not affect the 30 mM [K+]o-induced [Ca2+]i increase. D: test responses recorded at times 0 (red; τ = 5.6 s) and 60 (black; τ = 3.9 s) from a cell treated with calpeptin and primed with 30 mM [K+]o are superimposed on an expanded time scale. Heavy lines are exponential fits to the data. E: the time constant for [Ca2+]i recovery (τ) was normalized to the initial time constant (τ/τo) prior to the depolarizing priming stimulus (▪) and plotted vs. time. Plots are from representative cells (shown in A and B and C and D) recorded in the absence (○) and presence (▴) of 10 μM calpeptin.

Because the [Ca2+]i increases induced by the NMDA and 30 mM K+ priming stimuli were comparable, but subsequent changes in PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance were different, we examined the effects of priming with different concentrations of NMDA. The [Ca2+]i increases evoked by 10, 30, and 100 μM NMDA were graded with peak values ranging from 436 to 1,896 nM. There was no correlation between the amplitude of the Ca2+ increase and subsequent changes in PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i recovery kinetics (r2<0.01; n = 19). Thus global changes in [Ca2+]i did not predict changes in PMCA function. Perhaps depolarization and NMDA create stimulus-dependent Ca2+ microdomains that are not resolved by the whole cell measurements used here.

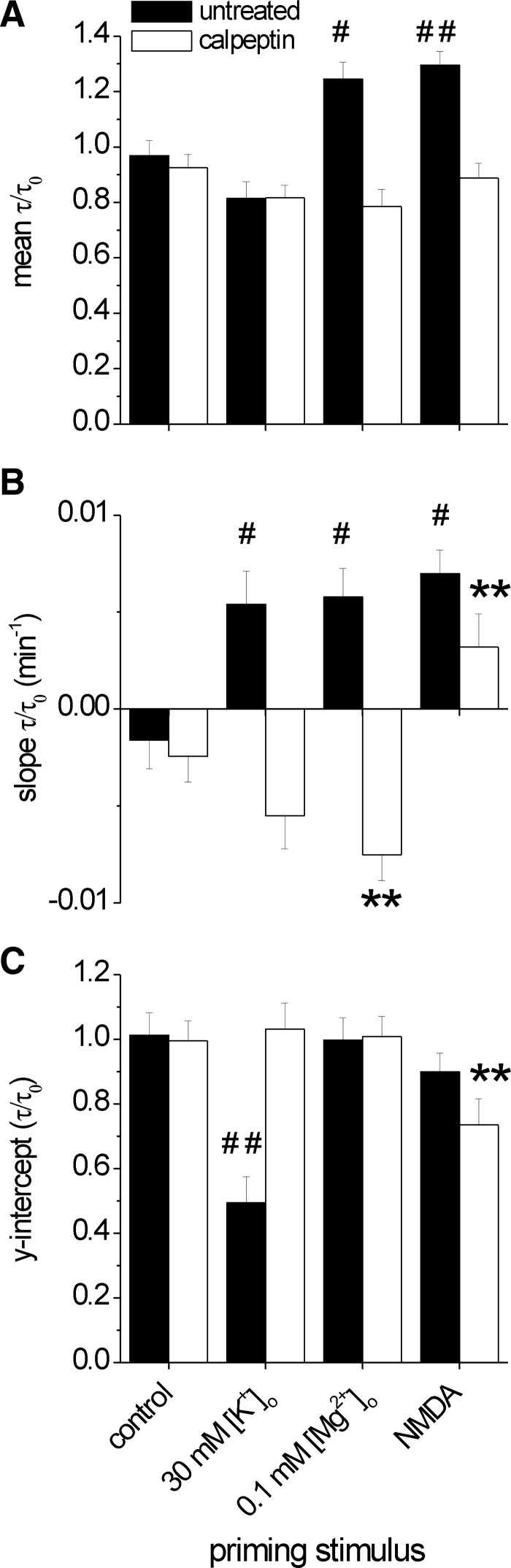

Stimulus-induced time-dependent changes in PMCA function are dependent on the Ca2+ source

To compare the changes in PMCA function resulting from each of the stimuli, we analyzed our entire data set. First we compared the effects of each stimulus on the change in τ for both untreated (▪) and calpeptin (□) conditions (Fig. 6A). τ did not significantly change under control conditions or following depolarization (30 mM K+). However, activation of NMDA receptors either directly or via synaptic activity (0.1 mM [Mg2+]o) produced a long-term slowing of PMCA function (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). Calpain mediated this slowing as indicated by significantly reduced mean τ values for cells treated with NMDA (P < 0.001) and 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o (P < 0.01) in the presence of calpeptin. We have previously described a glutamate-induced, calpain-mediated slowing of PMCA function that correlated with internalization of the PMCA (Pottorf et al. 2006). However, we did not observe a detectable internalization of PMCA over the much shorter time course (1 vs. 4 h) studied here (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Ca2+ source specific modulation of PMCA function. A–C: bar graphs summarize pooled data from time-dependent changes in τ/τ0 evoked by the following priming stimuli: none (control), depolarization (30 mM [K+]o), excitatory synaptic activity (0.1 mM [Mg2+]o) and 100 μM NMDA. # and *, significant comparison (univariate ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test) to the matching control condition. #, untreated condition; *, 10 μM calpeptin condition (* or # P < 0.05; ** or ## P < 0.01). All significant comparisons noted below. A: mean τ/τ0. Only in the untreated condition did priming stimuli differ from each other, # [F(3,15) = 11.22, P < 0.001]. The means of the control and 30 mM [K+]o are both smaller than 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o (P < 0.05, P < 0.01) and NMDA (P < 0.01, P < 0.001). The difference between untreated and calpeptin means (t-test with equal variance not assumed) was significant for 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o (t5.6 = 4.07; P < 0.01) and NMDA (t8.7 = 4.44, P < 0.001) primes. B: the slope of the linear regression. Slopes of the time-dependent changes in τ/τ0 following priming stimuli differed in the untreated condition [F(3,13) = 5.35, P < 0.05] with the control slope smaller than the other 3 conditions (P < 0.05); and in the calpeptin condition [F(3,12) = 15.03, P < 0.001], the NMDA slope is different from the other 3 (P < 0.01), and the 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o slope was different from control (P < 0.01). Comparison of untreated and calpeptin shows significant differences between slopes of 30 mM [K+]o (t4 = 4.91, P < 0.01), 0.1 mM [Mg2+]o (t3.7 = 5.62, P < 0.01) and NMDA (t5.5 = 2.4, P < 0.05). C: y intercept of the linear regression. Y intercept of the regression fit to time-dependent changes in τ/τ0 following priming stimuli differed in the untreated condition [F(3,13) = 6.7, P < 0.01], the line fit to kinetics data following 30 mM [K+]o had a smaller intercept relative to the other conditions (P < 0.01); and in the calpeptin condition [F(3,12) = 6.16, P < 0.01)], the NMDA intercept was smaller than the other 3 (P < 0.01). Error bars indicate ±SE.

The mean data show differences between test conditions but do not represent change over time. To assess this dynamic, a linear regression was performed on each series of time points recorded after the priming period and the slope and y intercept of the experiments that significantly matched a linear fit (33 of total of 41 experiments) are presented in Fig. 6, B and C, respectively. Figures 2C, 3B, 4E, and 5E show examples of the recovery data for each priming condition and the fitted regression lines. The slope of the line reveals the rate of change of the PMCA-mediated recovery kinetics over the course of the experiment (Fig. 6B) and the projected initial rate of PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i clearance is provided by the y intercept (Fig. 6C).

All three stimuli produced a graded slowing in PMCA function (Fig. 6B) and differed significantly from control (P < 0.05). However, note that the y intercept derived from the plot of τ/τo versus time was significantly lower than control in 30 mM [K+]o-treated cells (Fig. 6C; P < 0.01). The change in the regression y-intercept (τ/τo) suggests that activation of VGCCs induced rapid changes in PMCA activity that occurred during the stimulus. The rapid depolarization-induced acceleration (Fig. 6C) as well as the gradual slowing that developed following all three stimuli were blocked by calpeptin (Fig. 6B). Thus depolarization appears to activate calpain to produce a rapid stimulation of the PMCA followed by a more slowly developing inactivation. Only the slowly developing inactivation was observed following NMDA. Depolarization or intense synaptic activity (0.1 mM [Mg2+]o) induced a graded acceleration of PMCA-mediated [Ca2+]i clearance in the presence of calpeptin (P < 0.01 relative to control).

DISCUSSION

Following increases in [Ca2+]i, PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance underwent time- and stimulus-dependent changes in kinetics. Activation of NMDA receptors either directly or through excitatory synaptic activity induced a graded slowing of PMCA function that was mediated by calpain. In contrast, depolarization-induced activation of VGCCs induced an initial acceleration of PMCA activity followed by a graded slowing that was also mediated by calpain. With calpain blocked, synaptically induced increases in [Ca2+]i induced a graded acceleration in PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance. Thus we resolved three Ca2+-induced changes in PMCA function, a graded slowing, a rapid acceleration and a graded acceleration; the predominant effect was determined by the specific source of Ca2+ and the presence of functional calpain.

The slowly developing loss of PMCA activity followed all three stimuli. Because the [Ca2+]i was at basal levels during the progressive loss of PMCA function, the process was triggered by the stimulus-induced [Ca2+]i increase but once started continued in the absence of elevated [Ca2+]i. The block of this process by calpeptin suggests that the most parsimonious explanation for this sustained Ca2+-independent change in pump function is the autocatalytic activation of calpain. In the presence of a large, sustained increase in [Ca2+]i, calpain undergoes autoproteolysis that reduces the [Ca2+]i required for activation (Goll et al. 2003). Large increases in [Ca2+]i may also alter other aspects of calpain regulation such as inhibition by calpastatin. There are sites for calpain cleavage that are known to inactivate certain PMCA isoforms (Brown and Dean 2007). However, we do not know whether calpain acts directly on the PMCA or acts on one of its many other substrates to indirectly inhibit pump function (Goll et al. 2003; Wu and Lynch 2006). We have previously shown that the PMCA internalizes 4 h after starting a 30-min treatment with glutamate (Pottorf et al. 2006). The internalization required calpain activation and was accompanied by a loss of function. We were not able to detect PMCA internalization using the 10-min stimulus protocol employed in this study; whether this was due to insufficient resolution to detect small changes in PMCA distribution or whether pump inactivation precedes internalization is not clear. Both NMDA and low [Mg2+]o stimuli are potentially toxic, so the loss of PMCA activity following these treatments may contribute to the [Ca2+]i dysregulation that is a hallmark of excitotoxicity (Randall and Thayer 1992). The depolarization-induced slowing of PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance follows more rapid acceleration and thus may be a homeostatic process.

The biphasic changes in PMCA function induced by 30 mM [K+]o suggest a two-step process. The initial acceleration appears similar to the depolarization-induced stimulation of PMCA function described for sensory neurons (Pottorf and Thayer 2002) and fits well with a model of rapid Ca2+-induced stimulation of PMCA activity that slowly inactivates due to the slow dissociation of calmodulin from certain PMCA isoforms (Caride et al. 2001). However, because calpeptin prevented the stimulation, our data are more consistent with the proteolytic activation of the PMCA by calpain-mediated cleavage of the inhibitory domain on the carboxyl terminus (James et al. 1989). The return to basal activity may be via the same mechanism as the loss of function following NMDA. In this scenario, calpain first activates the pump by cleavage of the carboxyl terminus followed by a secondary inactivation mediated either by direct proteolysis of an inactivating site on the PMCA (Brown and Dean 2007) or via indirect mechanisms (Goll et al. 2003; Wu and Lynch 2006).

This conclusion raises the question as to why we do not see the initial activation of PMCA function in NMDA-treated cells; after all, NMDA activated calpain too. Because the rate of PMCA inactivation following all three stimuli was similar (no statistical difference between the slopes in Fig. 6B), it seems implausible that the inactivation mechanism is more rapid following NMDA receptor activation. Perhaps the C-terminal calpain cleavage site is less accessible to calpain activated by NMDA receptor-mediated relative to VGCC-mediated Ca2+ influx. The susceptibility of certain calpain substrates to cleavage is regulated by phosphorylation. For example, phosphorylation of the NR2b subunit by the kinase fyn increases the susceptibility of the NMDA receptor to calpain-mediated cleavage (Wu et al. 2007). Calmodulin binding to the PMCA protects a C-terminal cleavage site by shielding it from calpain (Padanyi et al. 2003), establishing a precedent for modulation of PMCA susceptibility as a substrate. We speculate that the various stimuli differentially activate rapid, Ca2+-dependent processes that modulate PMCA susceptibility to C-terminus cleavage by calpain. The differential localization of Ca2+-sensitive signaling cascades at NMDA receptor versus VGCC by attachment to scaffolding proteins is well documented (Sattler et al. 1999; Weick et al. 2003).

The selective activation of a Ca2+ sensitive signaling cascade may also explain the slowly developing acceleration that follows exposure to low [Mg2+]o in the presence of calpeptin. The slowly developing nature of the increase in PMCA activity would seem to rule out direct activation by Ca2+-calmodulin. Kinase activation would be a suitable mechanism in that PMCAs can be stimulated by phosphorylation (Penniston and Enyedi 1998; Usachev et al. 2002) and Ca2+-induced auto-phosphorylation is known to produce sustained kinase activity in neurons (Lisman et al. 2002). Whatever the mechanism, it appears that Ca2+ influx via VGCCs is able to stimulate PMCA activity but not Ca2+ influx via NMDA receptors. Because the slowly developing acceleration is only apparent in the presence of calpeptin, its relevance to cell signaling is unclear. It appears to be dominated by the calpain-mediated slowing of pump function consistent with the idea that calpain inactivates the pump irreversibly. Perhaps under other conditions or following different stimuli an acceleration of PMCA activity is more pronounced. Identifying these conditions and the mechanism are interesting future directions.

The large increase in [Ca2+]i induced by the priming stimuli studied here would be expected to increase mitochondrial Ca2+ levels. A prolonged elevation in [Ca2+]i due to mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering could not account for changes in PMCA function described here because the [Ca2+]i was allowed to recover to basal levels before test stimuli were applied to determine PMCA kinetics. Ca2+-induced, mitochondrial-mediated changes in cytoplasmic pH or ATP levels (Wang et al. 1994) could influence the ATP-dependent Ca2+-H+ exchange mediated by the PMCA (Thomas 2008). However, Ca2+ taken up into the mitochondria following stimuli that evoke large Ca2+ loads is eventually removed from the mitochondrial matrix (Wang and Thayer 1996; Werth and Thayer 1994), which would seem at odds with the idea that matrix Ca2+ levels produced the graded slowing in PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance.

Changes in the rate of Ca2+ clearance modulate both physiological and pathological function. For example, Ca2+ clearance from dendritic spines is slowed following stimuli that induce long-term potentiation of synaptic transmission (Scheuss et al. 2006) and neurotoxic stimuli induce Ca2+ dysregulation that contributes to cell death (Mattson et al. 1992; Randall and Thayer 1992). Activation of protein kinase C in sensory neurons stimulated PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance resulting in an increase in excitability due to reduced activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Usachev et al. 2002). Thus it is important to understand how specific stimuli influence PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance. Clearly stimuli that induced excitotoxicity such as NMDA and 0.1 mM Mg2+-induced synaptic activity slowed Ca2+ clearance, whereas depolarization, a stimulus that triggers Ca2+ influx via VGCC and does not reduce survival, did not produce a net change in Ca2+ clearance rate. Transient decreases in Ca2+ clearance might modify Ca2+ signaling by lowering the stimulus threshold for initiating Ca2+ triggered events and by prolonging the duration of Ca2+ signals. Mutations in PMCA genes that reduce function are genetic modifiers that in the case of PMCA2 increase the risk for noise-induced, Ca2+-dependent damage to the auditory system (Kozel et al. 2002).

Depolarization-induced increases in [Ca2+]i were larger than those induced by 100 μM NMDA but did not produce a net change in Ca2+ clearance rate. We interpret this result to indicate that the source of Ca2+ determined the subsequent response. There is precedent for different Ca2+ sources activating distinct signaling cascades. For example, NMDA-evoked Ca2+ entry activates nitric oxide synthase (NOS), whereas a comparable depolarization-induced increase in cellular [Ca2+]i did not. This selectivity resulted from the localization of NOS close to the mouth of the NMDA-gated ion channel such that it experienced a [Ca2+]i increase much higher than the global increase that spread throughout the cytoplasm (Sattler et al. 1999; Weick et al. 2003). The arrangement of Ca2+ sensitive signaling molecules on scaffoldings close to the mouth of Ca2+ permeable ion channels accounts for the selective activation of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) by Ca2+ entry via L-type Ca2+ channels (Sattler et al. 1999; Weick et al. 2003). We speculate that localization of PMCAs to specific Ca2+ microdomains enables selective modulation of Ca2+ pumps to serve local needs.

Conclusion

The principal finding from this study is that the mechanism of Ca2+-dependent modulation of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump in hippocampal neurons depends on the source of Ca2+. Calpain is clearly an important regulator of PMCA function following large [Ca2+]i increases. The differing effects of depolarization- versus NMDA-induced [Ca2+]i increases on PMCA function suggest that Ca2+ clearance may be selectively modulated within Ca2+ channel microdomains in neurons.

GRANTS

National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant DA-07304 and National Science Foundation Grant IOS0814549 supported this work.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Cushman for PMCA imaging data.

REFERENCES

- Benham et al. 1992.Benham CD, Evans ML, McBain CJ. Ca2+ efflux mechanisms following depolarization evoked calcium transients in cultured rat sensory neurons. J Physiol 455: 567–583, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown and Dean 2007.Brown CS, Dean WL. Regulation of plasma membrane Ca(2+)-ATPase in human platelets by calpain. Platelets 18: 207–211, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli 1994.Carafoli E Biogenesis: Plasma membrane calcium ATPase: 15 years of work on the purified enzyme. FASEB J 8: 993–1002, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli and Brini 2000.Carafoli E, Brini M. Calcium pumps: structural basis for and mechanism of calcium transmembrane transport. Curr Opinion Chem Biol 4: 152–161, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caride et al. 2001.Caride AJ, Penheiter AR, Filoteo AG, Bajzer Z, Enyedi A, Penniston JT. The plasma membrane calcium pump displays memory of past calcium spikes. Differences between isoforms 2b and 4b. J Biol Chem 276: 39797–39804, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco and Strehler 2001.DeMarco SJ, Strehler EE. Plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase isoforms 2b and 4b interact promiscuously and selectively with members of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase family of PDZ (PSD95/DLG/ZO-1) domain-containing proteins. J Biol Chem 276: 21594–21600, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Empson et al. 2007.Empson RM, Garside ML, Knopfel T. Plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase 2 contributes to short-term synapse plasticity at the parallel fiber to Purkinje neuron synapse. J Neurosci 27: 3753–3758, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi et al. 1991.Enyedi A, Filoteo AG, Gardos G, Penniston JT. Calmodulin-binding domains from isozymes of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump have different regulatory properties. J Biol Chem 266: 8952–8956, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi et al. 1996.Enyedi A, Verma AK, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT. Protein kinase C activates the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump isoform 4b by phosphorylation of an inhibitory region downstream of the calmodulin-binding domain. J Biol Chem 271: 32461–32467, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi et al. 1994.Enyedi A, Verma AK, Heim R, Adamo HP, Filoteo AG, Strehler EE, Penniston JT. The Ca2+ affinity of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump is controlled by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem 269: 41–43, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll et al. 2003.Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei WEI, Cong J. The Calpain System. Physiol Rev 83: 731–801, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz et al. 1985.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James et al. 1989.James P, Vorherr T, Krebs J, Morelli A, Castello G, McCormick DJ, Penniston JT, De Flora A, Carafoli E. Modulation of erythrocyte Ca2+-ATPase by selective calpain cleavage of the calmodulin-binding domain. J Biol Chem 264: 8289–8296, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozel et al. 2002.Kozel PJ, Davis RR, Krieg EF, Shull GE, Erway LC. Deficiency in plasma membrane calcium ATPase isoform 2 increases susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss in mice. Hear Res 164: 231–239, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman et al. 2002.Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioral memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 3: 175–190, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson et al. 1992.Mattson MP, Cheng B, Davis D, Bryant K, Lieberburg I, Rydel RE. β-Amyloid peptides destabilize calcium homeostasis and render human cortical neurons vulnerable to excitoxicity. J Neurosci 12: 376–389, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod et al. 1998.McLeod JR, Shen M, Kim DJ, Thayer SA. Neurotoxicity mediated by aberrant patterns of synaptic activity between rat hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurophysiol 80: 2688–2698, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison and Griffith 1998.Murchison D, Griffith WH. Increased calcium buffering in basal forebrain neurons during aging. J Neurophysiol 80: 350–364, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padanyi et al. 2003.Padanyi R, Paszty K, Penheiter AR, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT, Enyedi A. Intramolecular interactions of the regulatory region with the catalytic core in the plasma membrane calcium pump. J Biol Chem 278: 35798–35804, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penniston and Enyedi 1998.Penniston JT, Enyedi A. Modulation of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. J Membr Biol 165: 101–109, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piser et al. 1994.Piser TM, Lampe RA, Keith RA, Thayer SA. ω-Grammotoxin blocks action-potential-induced Ca2+ influx and whole-cell Ca2+ current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Pfluger's Arch Eur J Physiol 426: 214–220, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottorf et al. 2006.Pottorf WJ, Johanns TM, Derrington SM, Strehler EE, Enyedi A, Thayer SA. Glutamate-induced protease-mediated loss of plasma membrane Ca pump activity in rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem 98: 1646–1656, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottorf and Thayer 2002.Pottorf WJ, Thayer SA. Transient rise in intracellular calcium produces a long-lasting increase in plasma membrane calcium pump activity in rat sensory neurons. J Neurochem 83: 1002–1008, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall and Thayer 1992.Randall RD, Thayer SA. Glutamate-induced calcium transient triggers delayed calcium overload and neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 12: 1882–1895, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose et al. 1990.Rose K, Christine C, Choi D. Magnesium removal induces paroxysmal neuronal firing and NMDA receptor-mediated neuronal degeneration in cortical cultures. Neurosci Lett 115: 313–317, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler et al. 1999.Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, Hafner M, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M. Specific coupling of NMDA receptor activation to nitric oxide neurotoxicity by PSD-95 protein. Science 284: 1845–1848, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuss et al. 2006.Scheuss V, Yasuda R, Sobczyk A, Svoboda K. Nonlinear [Ca2+] signaling in dendrites and spines caused by activity-dependent depression of Ca2+ extrusion. J Neurosci 26: 8183–8194, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer et al. 1995.Stauffer TP, Guerini D, Carafoli E. Tissue distribution of the four gene products of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. A study using specific antibodies. J Biol Chem 270: 12184–12190, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler and Zacharias 2001.Strehler EE, Zacharias DA. Role of alternative splicing in generating isoform diversity among plasma membrane calcium pumps. Physiol Rev 81: 21–50, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer et al. 1988.Thayer SA, Sturek M, Miller RJ. Measurement of neuronal Ca2+ transients using simultaneous microfluorimetry and electrophysiology. Pfluger's Arch Eur J Pharmacol 412: 216–223, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer et al. 2002.Thayer SA, Usachev YM, Pottorf WJ. Modulating Ca2+ clearance from neurons. Front Biosci 7: D1255–1279, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas 2008.Thomas RC The plasma membrane calcium ATPase (PMCA) of neurones is electroneutral and exchanges 2 H+ for each Ca2+ or Ba2+ ion extruded. J Physiol 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Usachev et al. 2002.Usachev YM, DeMarco SJ, Campbell C, Strehler EE, Thayer SA. Bradykinin and ATP accelerate Ca2+ efflux from rat sensory neurons via protein kinase C and the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump isoform 4. Neuron 33: 113–122, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev et al. 2006.Usachev YM, Marsh AJ, Johanns TM, Lemke MM, Thayer SA. Activation of protein kinase C in sensory neurons accelerates Ca2+ uptake into the endoplasmic reticulum. J Neurosci 26: 311–318, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. 1994.Wang GJ, Randall RD, Thayer SA. Glutamate-induced intracellular acidification of cultured hippocampal neurons demonstrates altered energy metabolism resulting from Ca2+ loads. J Neurophysiol 72: 2563–2569, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang and Thayer 1996.Wang GJ, Thayer SA. Sequestration of glutamate-induced Ca2+ loads by mitochondria in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol 76: 1611–1621, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick et al. 2003.Weick JP, Groth RD, Isaksen AL, Mermelstein PG. Interactions with PDZ proteins are required for L-Type calcium channels to activate cAMP response element-binding protein-dependent gene expression. J Neurosci 23: 3446–3456, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth and Thayer 1994.Werth JL, Thayer SA. Mitochondria buffer physiological calcium loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci 14: 348–356, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth et al. 1996.Werth JL, Usachev YM, Thayer SA. Modulation of calcium efflux from cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci 16: 1008–1015, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al. 2007.Wu H-Y, Hsu F-C, Gleichman AJ, Baconguis I, Coulter DA, Lynch DR. Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of NR2B Tyr-1336 controls calpain-mediated NR2B cleavage in neurons and heterologous systems. J Biol Chem 282: 20075–20087, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu and Lynch 2006.Wu HY, Lynch DR. Calpain and synaptic function. Mol Neurobiol 33: 215–236, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi et al. 2003.Zaidi A, Barron L, Sharov VS, Schoneich C, Michaelis EK, Michaelis ML. Oxidative inactivation of purified plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase by hydrogen peroxide and protection by calmodulin. Biochem 42: 12001–12010, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenisek and Matthews 2000.Zenisek D, Matthews G. The role of mitochondria in presynaptic calcium handling at a ribbon synapse. Neuron 25: 229–237, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]