Abstract

BACKGROUND

Laparoscopic colectomy has become the standard of care for elective resections; however, there are few data regarding laparoscopy in the emergency setting.

METHODS

Using a prospectively collected database, we identified 94 patients who underwent an emergency colectomy between August 2005 and July 2008. Laparoscopic operations were performed in 42 patients and were compared to 25 who were suitable for laparoscopy but received open colectomy.

RESULTS

The groups had similar demographics with no difference in age, gender or surgical indications. Blood loss was lower (118ml vs. 205ml, p <0.01) and postoperative stay shorter (8 vs. 11 days, p = 0.02) in the laparoscopic patients, and perioperative mortality rates were similar between the two groups (1 vs. 3, p = 0.29).

CONCLUSIONS

With increasing experience, laparoscopic colectomy is a feasible option in certain emergency situations and is associated with shorter hospital stay, less morbidity, and similar mortality to that of open operation.

SUMMARY

Laparoscopic colectomy has become the standard of care for elective resections; however, there are few data regarding laparoscopy in the emergency setting. We demonstrate that increasing experience, laparoscopic colectomy is a feasible option in certain emergency situations and is associated with shorter hospital stay, less morbidity, and similar mortality to that of open operation.

Keywords: laparoscopic emergency colectomy, emergent colectomy, urgent colectomy laparoscopy, colectomy

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic colectomy has become the standard of care for elective management of benign and malignant colonic disease. Prospective randomized studies and systematic reviews have demonstrated the advantages of laparoscopic over open colectomy for elective surgery [1–5]. Despite these advantages, there are few data evaluating laparoscopy for emergency colorectal procedures and there is skepticism regarding potential benefits [6].

Studies examining laparoscopy in the non-elective setting have evaluated acute colitis, obstructing colon cancer and total colectomy; however, numbers have been small and generally report unmatched case series or single pathologies [7–9]. In order to further our understanding of the feasibility of using laparoscopy in the emergency setting, this study compares clinical outcomes between laparoscopic and open surgery for left, right and total colectomy for a variety of different pathologies in the emergent and urgent settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Using an institutional review board approved, prospectively collected patient database, we identified 94 patients who underwent emergency colectomy between August 2005 and July 2008. Additional patient demographics, indications for surgery, operative details, and postoperative complications were collected retrospectively via chart review following approval by the University Hospitals of Cleveland’s Institutional Review Board. Laparoscopic emergency colectomies were performed in 42 consecutive patients who were compared to 25 open emergency colectomy patients. Patients were carefully selected based on prior surgery, physical condition of patient, obesity, pathology, procedure, operative note review, and a discussion about case suitability for laparoscopy with the attending surgeon. Emergency colectomy included both emergent and urgent colectomy, and was considered emergent if the procedure was booked as an emergency mandating the operating room staff has a team available as soon as possible. A procedure was considered urgent, if the patient was unable to be discharged because of their deteriorating condition and then underwent surgery while in the hospital.

Diagnoses included bowel obstruction, perforated viscus, fulminant colitis, ischemia or uncontrollable gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Patients requiring with severe hemodynamic lability on inotropes, toxic megacolon, peritonitis in the setting of morbid obesity, prior colectomy or a body mass index > 55 were excluded from the open colectomy group as they would not have been suitable for laparoscopic colectomy. No patient received a preoperative bowel preparation. Conversion was defined as an incision over eight centimeters or operating through the extraction incision. All conversions were included in the laparoscopic group for analysis based on an intention to treat model.

Age, gender, body mass index, admission date, admission status, operative date, operation, time to flatus, time to first bowel movement, intra-operative complications, postoperative complications, discharge date, and discharge status were collected prospectively. Previous abdominal operations, comorbidities, indication for surgery, operative time, estimated blood loss, time to resuming diet, time to full ambulation, post-operative diagnosis, and 30 day re-admission rate were collected retrospectively.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA™ 9.1 (©StatCorp; College Station, Texas, USA). A two-sided unpaired Student’s T-test was used for normally-distributed continuous variables, and two-sided Wilcoxon Rank-sum (Mann-Whitney U) tests were for non-parametric data. Chi-squared tests and Fisher’s Exact Test were used to compare proportions.

RESULTS

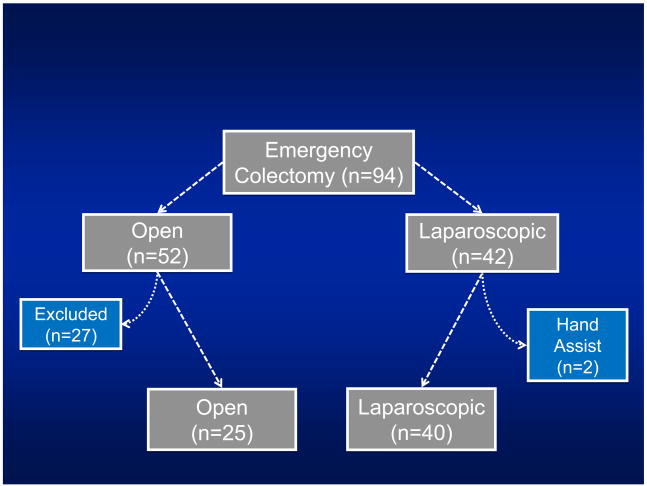

Ninety-four emergency colectomy cases were identified. Fifty-two patients underwent open emergency colectomies and 42 patients received laparoscopic emergency colectomies. Twenty-seven patients were excluded from the open group (Figure I) because of the above-mentioned criteria. Two patients were excluded from the laparoscopic group because of a primary hand assisted approach. Twenty (80%) of the open cases and 32 (80%) of the laparoscopic cases were emergent. There were four conversions in the laparoscopic group all of which were emergent.

Figure 1.

There was no difference between groups (Table I) in age (60.1 vs. 61.5, p=0.789), Body Mass Index (26.0 vs. 27.5, p=0.873), ASA grade (2.88 vs. 2.85, p=0.78), number of co-morbidities (1.9 vs. 1.9, 0.987), or number with prior abdominal surgery (60% vs. 53%, 0.55). Of the 20 laparoscopic patients with prior surgery, only one required conversion to open for adhesions. Types of co-morbidities and surgical risk factors were compared between groups with no significant differences except for smoking and drinking status, which were higher in the open group (p=0.02).

Table I.

Patient Characteristics at Presentation

| Open | Laparoscopic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Median) |

[Range] | Mean (Median) |

[Range] | P-value | |

| No. of Subjects | 25 | 40 | |||

| Age (years) | 60.1 (65) | [19–84] | 61.5 (63) | [18–93] | 0.789 |

| Female | 14 (56%) | 23 (58%) | 0.905 | ||

| Race (White) | 17 (68%) | 33 (83%) | 0.177 | ||

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.0 (24.9) | [19–36] | 27.5 (25.7) | [16–58] | 0.873 |

| Past Surgical History | 15 (60%) | 21 (52.5%) | 0.554 | ||

| ASA Grade | 0.777 | ||||

| 2 | 7 (28%) | 12 (30%) | |||

| 3 | 14 (56%) | 23 (58%) | |||

| 4 | 4 (16%) | 4 (10%) | |||

| 5 | 0 | 1 (3%) | |||

| Emergency Status (Emergent) | 20 (80%) | 32 (80%) | 1.000 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| DM | 6 (24%) | 6 (18%) | 0.549 | ||

| HTN | 10 (40%) | 17 (43%) | 0.842 | ||

| CAD | 4 (16%) | 11 (28%) | 0.371 | ||

| COPD | 2 (8%) | 4 (10%) | 1.000 | ||

| CRI | 3 (12%) | 6 (15%) | 1.000 | ||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 5 (20%) | 11 (28%) | 0.495 | ||

| CHF | 2 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 0.635 | ||

| Afib | 4 (16%) | 3 (8%) | 0.415 | ||

| Other Risk Factors | |||||

| Hx Ca | 1 (4%) | 3 (8%) | 0.568 | ||

| Dx Ca | 3 (12%) | 7 (18%) | 0.729 | ||

| Hx MI | 1 (4%) | 5 (13%) | 0.393 | ||

| Hx Stroke | 3 (12%) | 0 | 0.053 | ||

| Hx Crohns | 3 (12%) | 4 (10%) | 1.000 | ||

| Hx UC | 2 (8%) | 6 (15%) | 0.471 | ||

| Current Steroid Use | 5 (20%) | 10 (25%) | 0.642 | ||

| Recent Chemotherapy | 1 (4%) | 4 (10%) | 0.377 | ||

| Current Smoker | 11 (44%) | 7 (18%) | 0.020 | ||

| Current Heavy Drinker | 9 (36%) | 5 (13%) | 0.020 | ||

| Preoperative Diagnosis | 0.493 | ||||

| Acute Colitis | 8 (32%) | 11 (28%) | |||

| Perforated Viscus - DR | 9 (26%) | 12 (30%) | |||

| Perforated Viscus - Ia | 1 (4%) | 2 (5%) | |||

| Obstruction | 4 (16%) | 8 (20%) | |||

| Ischemia | 3 (12%) | 2 (5%) | |||

| GI Bleed | 0 | 5 (13%) | |||

Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding

Abbreviations in table: DM=Diabetes Mellitus, HTN=Hypertension, CAD=Coronary Artery Disease, COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, CRI=Chronic Renal Insufficiency, CHF=Congestive Heart Failure, Afib=Atrial Fibrillation, Hx Ca=History of Cancer, Dx Ca=Diagnosis of Cancer on Admission, Hx MI=History of Myocardial Infarction, Hx=History, UC=Ulcerative Colitis, DR=Disease Related, Ia=Iatrogenic.

Mean operative time was 180 minutes (median=165) for the open group and 159 minutes (median = 160) for the laparoscopic group (p=0.105) (Table II). Blood loss was significantly greater in open cases. Primary anastomosis was performed in 16% of open patients and 37% of laparoscopic patients; however, the difference was not statistically significant (0.093).

Table II.

Intra-operative Statistics

| Open | Laparoscopic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Median) |

[Range] | Mean (Median) |

[Range] | P-value | |

| No. of Subjects | 25 | 40 | |||

| Laparoscopically Completed | -- | 36 (90%) | |||

| Type of Operation | |||||

| Right (LRH) | 7 (28%) | 11 (28%) | 0.574 | ||

| Left or Sigmoid (LLH) | 9 (36%) | 19 (48%) | |||

| Total (LTC) | 9 (36%) | 10 (25%) | |||

| Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | 205 (175) | 118 (100) | 0.006 | ||

| Urine Output (mL) | 198 (175) | 203 (175) | 0.541 | ||

| Operative Time (minutes) | 180 (165) | [120–300] | 159 (160) | [80–300] | 0.106 |

| Length of Incision (cm) | 19 (20) | [15–20] | 6 (5) | [3–20] | <0.01 |

| Intraoperative Blood Transfusion | 6 (24%) | 3 (8%) | 0.076 | ||

| Intraoperative Stoma | 21 (84%) | 25 (63%) | 0.093 | ||

| Intraoperative Complication | 0 | 3 (8%) | 0.279 | ||

Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding

Laparoscopic patients had less post-operative ileus with fewer days to flatus (7.2 vs. 5.2, p=0.04) and days to diet (8.7 vs. 6.2, p=0.02). A shorter postoperative stay (11.3 days vs. 7.9 days, p=0.025) was also noted. Average time in the ICU was also reduced (Table 3). To adjust for baseline differences in smoking status, drinking status, and source of admission, these variables were used as covariates in a risk-adjusted analysis of postoperative length of stay. None of the added covariates were statistically significant predictors of increased length of stay, and operative approach remained a strong although non-statistically significant predictor (p=0.07). The loss of statistical significance is most-likely due to small sample sizes and subsequent loss of power.

CONCLUSIONS

Few studies address the feasibility of laparoscopic colectomy in the emergency setting. In a case-control study comparing laparoscopic total colectomy for acute colitis with a matched open colectomy group, Marcello and colleagues found that laparoscopic total colectomy was feasible and led to a faster recovery [10]. Ng and colleagues used seven consecutive patients to study the role of emergency laparoscopically assisted right hemicolectomy for obstructing right-sided colon carcinoma, and found this approach demonstrated favorable short-term clinical outcomes and an acceptable number of lymph nodes removed [9]. Bleier and colleagues evaluated 11 laparoscopic patients and 7 open controls that had iatrogenic perforation after colonoscopy with all injuries being repaired without resection [12]. They found laparoscopy resulted in decreased morbidity, decreased length of stay, and gave a shorter incision than open controls. More recently, Fowkes et al. evaluated the role of laparoscopic subtotal emergency colectomy in medically resistant patients with ulcerative colitis and found that the approach was safe and reduced length of stay [11].

In the current study, we included patients that underwent laparoscopic colectomy in both the urgent and the emergent setting. Although two coauthors (CD and BC) have performed more than 500 laparoscopic colorectal procedures between 2005 and 2008, emergency laparoscopic colectomy is still being used sparingly in our practice. The present study revealed that laparoscopy can be used safely and effectively in the emergent setting for a variety of presentations, and that the outcomes achieved with this approach approximate those of a standard open approach. The lower number of complications, decreased average ICU stay and statistically significantly lower postoperative length of stay suggest that emergent laparoscopic colectomy is feasible.

This study builds on previous studies by adding an appropriate comparison group and by increasing the sample size used to evaluate the laparoscopic approach. As our understanding of the risks and benefits of laparoscopic equipment grows, further studies are needed to prospectively evaluate the role of laparoscopy in select emergency situations. It should also be stressed that the steep learning curve for elective laparoscopic colectomy must be overcome before these procedures are attempted in the urgent or emergent setting.

Table III.

Postoperative Outcomes

| Open | Laparoscopic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Median) |

[Range] | Mean (Median) |

[Range] | P-value | |

| No. of Subjects | 25 | 40 | |||

| Postoperative Course | |||||

| Time to Flatus (days) | 7.2 (5) | [2–20] | 5.2 (4) | [0–23] | 0.043 |

| Time to Bowel Movement (days) | 8.6 (7) | [2–30] | 5.9 (5) | [1–23] | 0.083 |

| Time to Regular Diet (days) | 8.7 (8) | [3–30] | 6.2 (5) | [1–23] | 0.016 |

| Time to Discharge (days)** | 11.3 (9) | [4–36] | 7.9 (7) | [2–25] | 0.025 |

| Early Postoperative Complications§ | 15 (63%) | 18 (46%) | 0.207 | ||

| Postoperative Early Complications*** | |||||

| ICU Stay Required | 12 (48%) | 13 (33%) | 0.211 | ||

| ICU Length of Stay | 7.6 (0) | [0–60] | 0.7 (0) | [0–5] | 0.052 |

| Total Parenteral Nutrition | 8 (35%) | 13 (33%) | 0.853 | ||

| Postoperative Intubation | 6 (25%) | 3 (8%) | 0.069 | ||

| Surgical Site Infection | 4 (17%) | 8 (21%) | 1.000 | ||

| Abscess | 2 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 1.000 | ||

| Deep Vein Thrombosis | 3 (13%) | 1 (3%) | 0.150 | ||

| Urinary Track Infection | 2 (8%) | 4 (10%) | 1.000 | ||

| Pneumonia | 2 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0.552 | ||

| Pulmonary Embolism | 1 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 1.000 | ||

| Myocardial Infarction | 2 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0.552 | ||

| Blood Transfusion Required | 5 (21%) | 3 (8%) | 0.241 | ||

| Dehiscence | 1 (4%) | 0 | 0.381 | ||

| Any Other | 4 (17%) | 3 (8%) | 0.412 | ||

| Discharge Status | |||||

| Home | 18 (72%) | 26 (65%) | 0.127 | ||

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 4 (16%) | 13 (33%) | |||

| 30 Day Complications | |||||

| Readmission within 30 days | 2 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 1.000 | ||

| Reoperation within 30 days | 1 (4%) | 2 (5%) | 1.000 | ||

| Mortality within 30 days | 2 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0.544 | ||

Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding

Time from Colectomy to Discharge (a.k.a. Post-operative Length of Stay)

There were none of the following: Anastomotic Leak, Fistula.

All Early Complications except ICU Stay and TPN

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported, in part, by grant T32 HS00059 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. In addition, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. provided unrestricted research funds that went towards salary support for JS.

Footnotes

DR. PHILIP D. KONDYLIS (Erie, Pennsylvania): Emergency laparoscopic surgery is a topic that would have evoked a visceral response even just ten years ago. Your series is a welcome addition to a somewhat sparse in the literature on urgent and emergent colorectal laparoscopic surgery. I have two question topics for you. Your classification of cases as urgent or emergency seems quite straight forward. Based on the surgical indications, however, some of these patients were more likely admitted prior to surgical consultation. How many of these patients went to the OR on their very first hospital day? What was the typical length of preoperative stay for patients not operated on the day of admission?

Second, two surgeons performing 500 laparoscopic colon cases over three years represents a very experienced team. Would you comment on the degree of increased difficulty with these urgent and emergent cases? Are these cases so inherently different as to incur a learning curve of their own?

And, finally, in your opinion, how many elective cases should one undertake before considering this type of surgery?

MR. STULBERG: Approximately 75 to 80 percent of our cases in both groups were considered emergent, requiring that they go to the operating room on the first day that they were seen by the surgical service. Unfortunately, we don’t have the number to give you on how many patients were sitting on medical services before their consultation to the surgical service, but we will certainly include that in a subanalysis.

Second, it has been communicated to me that the level of difficulty performing these cases in the emergency setting is certainly increased, but I think that I would have to defer to Dr. Champagne to answer your question about the learning curve.

DR. BRADLEY J. CHAMPAGNE (Cleveland, Ohio): Thanks, Phil. Regarding the appropriateness of introducing laparoscopic colectomy in the emergent setting into your practice and the learning curve, I think the best decision tree is the following: when you first evaluate the patient, ask yourself whether you would approach that patient electively with a laparoscopic colectomy based on their comorbidities and previous surgery. If the answer is “yes,” then you can entertain the question. More important than a number, one should consider the disease process itselfand what the procedure will entail in the patient. For instance, there is a huge spectrum of patients. Somebody with a perforated right colon after a colonoscopy, otherwise healthy, is completely different than an elderly patient with multiple comorbidities and C-difficile colitis. So when you’re comfortable doing elective laparoscopic colectomy, I would advise starting at the early end of the spectrum doing a total colectomy for a GI bleed where anatomical planes are not disturbed or a perforated colonoscopy, likewise, and also considering the patient comorbidities. Rather than a specific number, it is really disease based the surgery that’s required and the patient. I think once you’re comfortable doing laparoscopic elective colectomy, you can start entertaining these cases in the early end of the curve.

DR. AHMED A. MEGUID (St. Clair Shores, Michigan): I was wondering if you could comment on your leak rate. I notice the number of stomas you created on an urgent basis was actually I consider fairly low, so I was wondering if you had any data on that? If there is any difference between open versus laparoscopic.

MR. STULGER: Yes, we collect data on leak rates. There was no difference between the laparoscopic and open group. There were actually two leaks, both occurred in the open group.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lacy AM, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9325):2224–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2050–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1718–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrett KA, Champagne BJ, Valerian BT, Peterson D, Lee EC. A single training center’s experience with 200 consecutive cases of diverticulitis: Can all patients be approached laparoscopically? Surg Endosc. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9818-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SW, Yoo J, Dujovny N, Sonoda T, Milsom JW. Laparoscopic vs. hand-assisted laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(4):464–9. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0500-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Systematic review on the short-term outcome of laparoscopic resection for colon and rectosigmoid cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(5):375–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunker MS, Bemelman WA, Slors JF, van Hogezand RA, Ringers J, Gouma DJ. Laparoscopic-assisted vs open colectomy for severe acute colitis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a retrospective study in 42 patients. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(10):911–4. doi: 10.1007/s004640000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marohn MR, Hanly EJ, McKenna KJ, Varin CR. Laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy in the acute setting. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9(7):881–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.04.017. discussion 887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng SS, Yiu RY, Li JC, Lee JF, Leung KL. Emergency laparoscopically assisted right hemicolectomy for obstructing right-sided colon carcinoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16(4):350–4. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcello PW, Milsom JW, Wong SK, Brady K, Goormastic M, Fazio VW. Laparoscopic total colectomy for acute colitis: a case-control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(10):1441–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02234595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowkes L, Krishna K, Menon A, Greenslade GL, Dixon AR. Laparoscopic emergency and elective surgery for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10(4):373–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]