Abstract

Searches in an EST database from maize revealed the expression of a protein related to the Galanthus nivalis (GNA) agglutinin, referred to as GNAmaize. Heterologous expression of GNAmaize in Pichia pastoris allowed characterisation of the first nucleocytoplasmic GNA homolog from plants. GNAmaize is a tetrameric protein which shares 64% sequence similarity with GNA. Glycan microarray analyses revealed important differences in the specificity. Unlike GNA, which binds strongly to high-mannose N-glycans, the lectin from maize reacts almost exclusively with more complex glycans. Interestingly, GNAmaize prefers complex glycans containing β1-2 GlcNAc residues. The obvious difference in carbohydrate-binding properties is accompanied by a 100-fold reduced anti-HIV activity. Although the sequences of GNA and GNAmaize are clearly related they show only 28% sequence identity. Our results indicate that gene divergence within the family of GNA-related lectins leads to changes in carbohydrate binding specificity, as shown on N-glycan arrays.

Keywords: Galanthus nivalis agglutinin, glycan array, cytoplasmic homolog, human immunodeficiency virus, agglutination, lectin

Introduction

Lectins or agglutinins are a heterogeneous group of carbohydrate-binding proteins classified together on the basis of their ability to bind in a reversible way to well-defined simple sugars and/or complex carbohydrates. The wide distribution of lectins in different plant tissues suggests important physiological roles for these proteins [1]. Until a few years ago, most plant lectin research was focused on the classical vacuolar plant lectins that occur in reasonable to high concentrations in seeds or some specialized vegetative tissues. In recent years, evidence accumulated for the occurrence of nucleocytoplasmic plant lectins. Many of these cytoplasmic/nuclear plant lectins are expressed upon application of well-defined stress conditions, such as salt stress, drought or plant hormone treatment [1]. These new lectins are present in plant tissues in small quantities which makes it difficult to purify and characterize them.

One group of nucleocytoplasmic plant lectins are the homologs of the vacuolar mannose-binding Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) [1-2]. In the present work, a cytoplasmic GNA-like lectin expressed in Zea mays (referred to as GNAmaize) was cloned and successfully expressed in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. The coding sequence of the GNA homolog from maize differs from the G. nivalis agglutinin in that it lacks a signal peptide and C-terminal propeptide. It was shown previously that this change in targeting peptides results in a different subcellular localization of the protein. In contrast to GNA that is located in the vacuole, GNA homologs from rice and maize, that lack a signal peptide and C-terminal propeptide, are found in the nucleus and the cytoplasm [2-3]. Analysis of the recombinant protein using glycan microarrays demonstrated that recombinant GNAmaize has specificity towards complex N-glycans, in contrast to the vacuolar GNA from snowdrop which interacts particularly with high-mannose N-glycans. This change in carbohydrate-binding properties of the lectin also clearly affected its biological activity. The agglutination activity of GNAmaize is approximately 8-fold increased compared to that of GNA. In contrast to GNA which was shown to be a lectin with potent anti-HIV activity, GNAmaize revealed a strongly reduced antiviral effect.

Materials and methods

Expression of a cytoplasmic GNA-like lectin in Pichia pastoris

Cloning and expression of recombinant GNA-like lectin from Zea mays was performed using the EasySelect Pichia Expression Kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA USA). To achieve intracellular expression, the E. coli/P. pastoris shuttle vector pPICZB (Invitrogen) was selected carrying a polyhistidine tag located downstream from the multiple cloning site. The coding sequence for the GNA-like lectin from Z. mays was amplified by PCR from a pT7T3PAC vector containing the cDNA coding for this lectin (Genbank accession number BM351398) using primers ZmPi-f (5’ GGCGGAGAATTCACCATGGGT TACGGCACTCTCGACAACGG 3’) and ZmPi-r (5’ CCCGCTTTC TAGAATTTTGTTGCTCTTGGAAGACCAGAT 3’), and cloned as an EcoRI/XbaI fragment in the pPICZB vector. The P. pastoris wild-type strain X33 (Invitrogen) was transformed with pPICZ-GNAmaize using electroporation. For expression analysis a single recombinant P. pastoris X33 colony was inoculated into BMGY medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 1.34% yeast nitrogen base with ammonium sulfate and without amino acids, 4 × 10-5% biotin, 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0) and 1% glycerol). Expression was induced by transferring the cells to BMMY medium (BMGY medium supplemented with 1% of methanol instead of 1% of glycerol).

Purification of the lectin was achieved in three chromatographic steps. Cell pellets were extracted in 20 mM 1,3 diaminopropane. After centrifugation the supernatant was loaded on a Q Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with 20 mM 1,3 diaminopropane. Bound proteins were eluted using 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9) containing 0.5 M NaCl. Subsequently, the eluted fractions were pooled and applied on a Ni-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) to purify the His-tagged proteins. Finally fractions eluted from Ni-Sepharose were chromatographed into a Sephacryl S-100 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with 20 mM 1,3 diaminopropane at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. After each purification step, protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE.

Agglutination assay

The presence of lectin activity was checked by simple agglutination assays using trypsin-treated rabbit erythrocytes. Samples that yielded no visible agglutination activity after incubation for 1 h were regarded as lectin negative.

The lowest lectin concentration that showed activity was estimated by a semi-quantitative agglutination assay. Therefore, aliquots of serially 2-fold diluted purified protein were mixed with trypsin-treated rabbit erythrocytes in the wells of polystyrene 96U-welled microtiter plates. Agglutination was assessed visually after incubation for 1 h at room temperature.

Amino terminal sequence analysis and mass spectrometry

N-terminal sequencing was carried out on affinity purified protein fractions which were separated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted on a ProBlot™ polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA, USA). The membrane was stained with Coomassie briliant blue, and the proteins of interest were excised from the blot. The N-terminal sequence was determined by Edman degradation performed on a model Procise 491cLC protein sequencer without alkylation of cysteines (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA, USA).

Proteins purified by gel filtration were loaded on a Brownlee C8 Aquapore RP-300 column (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT, U.S.A.) in 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and eluted in an acetonitrile gradient in 0.1 % TFA. Proteins eluting from the column were detected by their U.V. adsorption at 214 nm and 2 % of the column effluent was split online to an electrospray ion trap mass spectrometer (Esquire-LC, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Profile MS spectra were averaged over the U.V. adsorption peaks and raw spectra were deconvoluted using Bruker deconvolution software to obtain the average Mr of proteins.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measurements were carried out using a Zetasizer Nano S (Malvern Instruments, UK) equipped with a 633nm He-Ne laser and a temperature-controlled measuring chamber. Purified GNAmaize at 0.37 mg/ml in 20 mM 1,3 diaminopropane was clarified by centrifugation for two hours at 16000 xg and the supernatant was then subjected to dynamic light scattering measurements at 20 °C.

Glycan array screening

The microarrays are printed as described before [4] and version 3.1 was used for the analyses reported here (https://www.functionalglycomics.org/static/consortium/resources/resourcecoreh8.shtml). The printed glycan array contains a library of natural and synthetic glycan sequences representing major glycan structures of glycoproteins and glycolipids. On the current array 377 glycan targets are included.

Recombinant GNAmaize, purified from Pichia pastoris and GNA, purified from snowdrop bulbs (1 mg/ml) were labeled using the Alexa Fluor® 488 Protein Labeling Kit from Invitrogen following the manufacturer’s instructions. The labeled lectins were diluted to 0.1 mg/ml for GNAmaize and 0.005 mg/ml for GNA and 70 μl of the labeled lectins was applied to separate microarray slides and incubated under a cover slip for 60 min in a dark, humidified chamber at room temperature. After the incubation, the cover slips are gently removed in a solution of Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 and washed by gently dipping the slides 4 times in successive washes of Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, Tris-buffered saline, and deionized water. After the last wash the slides are spun in a slide centrifuge for approximately 15 sec to dry and immediately scanned in a PerkinElmer ProScanArray MicroArray Scanner using an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and ImaGene softweare (BioDiscovery, Inc., El Segundo, CA) to quantify fluorescence. The data are reported as average Relative Fluorescence Units (RFU) of six replicates for each glycan presented on the array.

HIV assays

Human lymphocyte CEM cells (5 × 105 cells per ml) were suspended in fresh culture medium and infected with HIV-1(IIIB) or HIV-2(ROD) at 100 × the CCID50 per ml of cell suspension. Then, 100 μl of the infected cell suspension was transferred to 200 μl-microplate wells, mixed with 100 μl of the appropriate dilutions of the test compounds, and further incubated at 37°C. After 4 days, giant (syncytium) cell formation was recorded microscopically in the CEM cell cultures, and the number of giant cells was estimated as the percentage of the number of giant cells present in the non-treated virus-infected cell cultures (~ 50 to 100 giant cells in one microscopic field when examined at a microscopic magnitude of 100 ×). The 50% effective concentration (EC50) corresponds to the compound concentrations required to prevent syncytium formation by 50%. The 50% cytostatic concentration (CC50) corresponds to the compound concentrations required to inhibit CEM cell proliferation by 50%. In the co-cultivation assays, 5 × 104 persistently HIV-1 infected HUT-78 cells (designated HUT-78/HIV-1) were mixed with 5 × 104 SupT1 cells, along with appropriate concentrations of the test compounds. After 24 h, marked syncytium formation was noted in the control cell cultures, and the number of syncytia was determined under the microscope. The EC50 was defined as the compound concentration required to prevent syncytium formation by 50%.

Analytical methods

The protein content of the samples was estimated using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay, based on the Bradford [5] dye-binding procedure. SDS-PAGE was done using 15% polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions as described by Laemmli [6]. Proteins were visualised by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. For Western blot analysis, samples separated by SDS-PAGE were electrotransferred to 0.45 μm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Biotrace™ PVDF, PALL, Gelman Laboratory, Ann Arbor, MI USA). After blocking the membranes in Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS: 10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, pH 7.6) containing 5% (w/v) BSA, blots were incubated for 1 h with a mouse monoclonal anti-His (C-terminal) antibody (Invitrogen), diluted 1/5000 in TBS. The secondary antibody was a 1/1000 diluted rabbit anti-mouse IgG labelled with horse radish peroxidase (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Immunodetection was achieved by a colorimetric assay using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis Missouri, USA) as a substrate.

Results

Characterisation of recombinant GNA homolog from maize expressed in Pichia pastoris

Purification of the recombinant His-tag labelled protein was achieved using ion exchange chromatography, combined with immobilized metal affinity chromatography on a Ni-Sepharose column and gel filtration. Analysis of the recombinant protein by SDS-PAGE revealed two polypeptides of approximately 16 and 13.5 kDa. N-terminal protein sequence analysis by Edman degradation revealed identical sequences for both polypeptides. The N-terminal 20 amino acid sequence corresponded to GYGTLDNGDWLMVGMSIFSK, and is identical to the sequence deduced from the cDNA sequence with cleavage of the N-terminal methionine. Mass spectrometry yielded two major peaks of 15,639.2 Da and 13,274.9 Da. The mass of 15639.2 is in perfect agreement with the calculated size for the fusion protein consisting of the GNAmaize polypeptide fused to the c-myc epitope and the tag consisting of six histidine residues, taken also into consideration the cleavage of the N-terminal methionine residue (as shown by Edman degradation) and assuming the formation of one disulfide bond between the two cysteine residues (theoretical average Mr 15639.4). The size of the second peak corresponds to the same fusion polypeptide (without N-terminal Met) in which only the 3 first amino acids of the tag (Ile-Leu-Glu) are present (Mr 13,273.9).

The molecular mass of native recombinant GNAmaize was also estimated by dynamic light scattering. Initial dynamic light scattering measurements on purified GNAmaize revealed a rather polydisperse sample which could be clarified by extensive centrifugation. The main scattering peak corresponded to particles having an average hydrodynamic diameter of 6.8 nm consistent with globular protein assemblies of 60 kDa. Given a molecular weight of 15.7 kDa for the monomer, the dynamic light scattering data indicate that recombinant GNAmaize occurs as a tetramer.

Agglutination activity of recombinant GNA homolog from maize

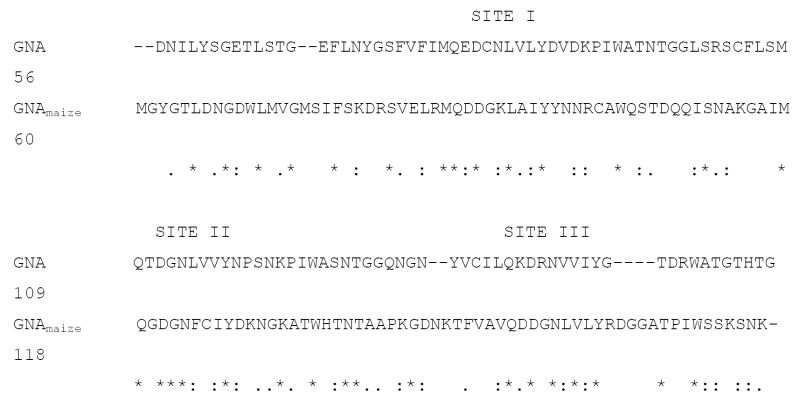

To study the biological activity of the recombinant lectin expressed in Pichia, the recombinant lectin was tested for its agglutination activity toward rabbit erythrocytes. Agglutination assays with the cell extracts as well as the purified GNAmaize revealed strong agglutination activity. These results are in agreement with the observation that one of the three carbohydrate binding motifs of GNA is completely conserved in the GNAmaize sequence. In the two other carbohydrate binding sites one (VΔC) or two amino acids (VΔA; NΔK) have been substituted (Fig. 1). Sequence comparison for the polypeptides encoding GNA and GNAmaize revealed 28% and 64% sequence identity and similarity, respectively.

Figure 1.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the GNA-like lectin from Zea mays (GNAmaize) and the mature GNA polypeptide. Conserved residues in the carbohydrate binding sites are boxed grey.

Determination of the lowest concentration that still gave lectin activity revealed that the cytoplasmic GNA homolog is –in terms of agglutination activity- considerably more active than the vacuolar GNA. The lowest lectin concentration that yielded agglutination activity was 1.7 μg/ml and 12.5 μg/ml for GNAmaize and GNA, respectively.

Carbohydrate-binding specificity of GNA and a cytoplasmic GNA homolog from maize

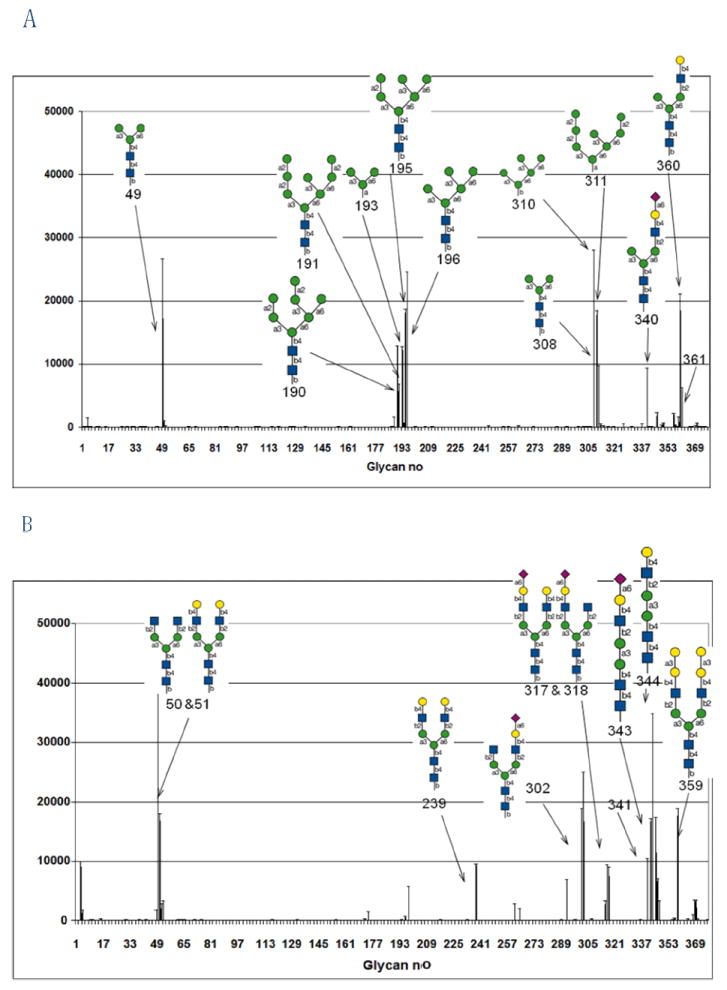

The carbohydrate-binding properties of the recombinant cytoplasmic GNA-like lectin from maize were investigated by screening the labeled protein on a glycan array, and compared to the sugar-binding specificity of that of GNA. The glycan array screening confirmed the strong interaction of GNA with high-mannose N-glycans and preferentially recognition of terminal mannose residues (Fig. 2, Table 1) [7-8]. In contrast, analysis of recombinant GNAmaize on the glycan array revealed that this GNA homolog has no affinity at all for high-mannose glycans (glycans #190-191-193-195-196) but instead exhibits a strong affinity for some complex N-glycans. Interestingly, GNAmaize appears to prefer some complex glycans containing β1-2 GlcNAc residues. These GlcNAc residues can be either in a terminal (glycan #50) or nonterminal (glycan #344) position. A comparison between glycans #49 (no terminal GlcNAc, high-mannose type) and #50 (terminal GlcNAc added to glycan #49) clearly shows that the complex type glycan #50 is favored by the cytoplasmic GNA homolog from maize whereas the high-mannose type glycan #49 is strongly recognized by the vacuolar GNA, but shows very low interaction with GNAmaize. Similarly, identical glycans #303 (terminal GlcNAc) and #308 (no terminal GlcNAc, high-mannose type) are preferentially recognized by GNAmaize and GNA, respectively. In addition, GNAmaize also shows good interaction with asialo glycans with some tolerance for the sialic acid in the 2-6 linkage (Fig. 2, Table 1). There is weak binding to glycan#53, which is the disialyl (2-6) biantennary glycan, but no binding to glycan#141, a disialyl (2-3) biantennary glycan. GNAmaize binds more strongly to monosialyl 2-6 glycans (#s 302, 317, 318, and 343). GNA also interacts with some complex N-glycans (glycans 340, 360, 361).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the glycan array results for GNA, purified from snowdrop bulbs and recombinant GNAmaize, purified from Pichia pastoris cells. Both analyses were done on the printed array v3.1 of the Consortium for Functional Glycomics. Error bars represent mean ± standard deviation. RFU = Relative Fluorescence Units. A) Glycan array analysis of GNA at a concentration of 5 μg/ml; B) Glycan array analysis of GNAmaize at concentration of 100 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Carbohydrate-binding specificity of GNA and recombinant GNAmaize as determined by the glycan array analysis using the Consortium for Functional Glycomics printed array v3.1. RFU = relative fluorescence units, % CV = Coefficient of variation expressed as %.

| Glycan No. | Structure | GNA, 5 μg/ml | GNAmaize, 100 μg/ml | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFU | % CV | RFU | % CV | ||

| N-linked, high-mannose type structures | |||||

| 196 | Manα1-6(Manα1-3)Manα1-6(Manα1-3)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4 GlcNAcb-Sp12 | 24080 | 4 | 16 | 128 |

| 308 | Manα1-3(Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 21490 | 61 | 226 | 74 |

| 195 | Manα1-6(Manα1-3)Manα1-6(Manα2Manα1-3)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 18132 | 6 | 116 | 48 |

| 310 | Manα1-6(Manα1-3)Manα1-6(Manα1-3)Manβ-Sp10 | 17721 | 8 | 9 | 480 |

| 49 | Manα1-3(Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 17195 | 110 | 871 | 203 |

| 190 | Manα1-6(Manα1-2Manα1-3)Manα1-6(Manα2Manα1-3)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 12725 | 3 | -2 | -606 |

| 193 | Manα1-3(Manα1-6)Manα-Sp9 | 12208 | 8 | 19 | 212 |

| 311 | Manα1-2Manα1-2Manα1-3(Manα1-2Manα1-6(Manα1-3)Manα1-6)Manα-Sp9 | 9207 | 12 | 20 | 153 |

| 191 | Manα1-2Manα1-6(Manα1-3)Manα1-6(Manα2Manα2Manα1-3)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 5733 | 41 | 43 | 45 |

| 360 | Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 18459 | 29 | 14 | 155 |

| 340 | Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp12 | 8605 | 19 | -5 | -423 |

| Complex N-glycan structures | |||||

| 50 | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 871 | 28 | 36093 | 21 |

| 344 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp12 | 55 | 44 | 34581 | 2 |

| 302 | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 60 | 53 | 17912 | 10 |

| 359 | Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp20 | 867 | 165 | 17580 | 14 |

| 51 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp13 | 229 | 17 | 16809 | 15 |

| 343 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp12 | 82 | 86 | 16727 | 5 |

| 303 | GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 31 | 24 | 16652 | 100 |

| 346 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp12 | 1749 | 66 | 11413 | 104 |

| 341 | Neu5Acα2-6Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc-Sp12 | 75 | 45 | 9954 | 11 |

| 239 | Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Fucα1-3(Galβ1-4)GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp20 | 41 | 35 | 9243 | 6 |

| 4 | Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3(Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6)Manβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAcβ-Sp19 | 1495 | 8 | 9091 | 19 |

| 361 | Galb1-3(Fuca1-4)GlcNAcb1-2Mana1-3[Galb1-3(Fuca1-4)GlcNAcb1-2Man a1-6]Manb1-4GlcNAcb1-4(Fuca1-6)GlcNAcb-Sp22 | 5658 | 23 | 22 | 200 |

Antiviral activity

GNA and GNAmaize were evaluated for their inhibitory activity against HIV-induced cytopathicity in human lymphocyte (CEM) cell cultures. GNA efficiently inhibited giant cell formation in the HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected cell cultures at a 50% effective concentration (EC50) of 0.34 ± 0.04 μg/ml (0.007 μM) and 0.41 ± 0.06 μg/ml (0.008 μM), respectively (Table 2). In contrast, GNAmaize was at least 50- to 100-fold less inhibitory [EC50: 28 ± 7.8 μg/ml (0.47 μM) and ≥ 50 μg/ml (≥ 0.83 μM), respectively]. The compounds were also investigated for their potential to prevent syncytium formation in co-cultures of persistently HIV-1-infected HUT-78 cells and uninfected lymphocyte SupT1 cells. GNA prevented syncytium formation in the co-cultures at an EC50 of 3.1 μg/ml (0.06 μM). GNAmaize was not inhibitory at 100 μg/ml (1.8 μM).

Table 2.

Anti-HIV-1 and -HIV-2 activity and cytostatic properties of GNA and GNAmaize in human T-lymphocyte (CEM) cells.

| EC50a (μg/ml) | IC50b (μg/ml) | CC50c (μg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | HIV-1 | HIV-2 | HUT-78/HIV-1 + Sup T.1 | |

| GNAmaize | 28 ± 7.8 | ≥50 | > 100 | > 50 |

| GNA | 0.34 ± 0.035 | 0.41 ± 0.064 | 3.1 ± 3.2 | > 50 |

EC50 = effective concentration or compound concentration required to protect CEM cells against the cytopathicity of HIV by 50%.

CC50 = cytotoxic concentration or compound concentration required to reduce CEM cell viability by 50 %

IC50 = inhibitory concentration or compound concentration required to prevent syncytium formation between persistently HIV-1-infected HUT-78/HIV-1 cells and uninfected lymphocyte Sup T.1 cells

Discussion

The G. nivalis agglutinin was first purified in 1987 from snowdrop bulbs [9]. Since then, homologous genes and proteins have been reported in a variety of plants [1, 8]. Many of these plants express the vacuolar form of GNA. However, in recent years there have been reports of sequences with similarity to GNA that locate to the nucleocytoplasmic compartment [2]. In addition, it was shown that the (nucleo)cytoplasmic and vacuolar lectins are evolutionary related [10].

At present little if no information is available for these nucleocytoplasmic GNA homologs at the protein level. Since these lectins are expressed at very low levels, it is rather difficult to purify the lectin from the plant tissues in which they occur. To overcome this problem an expression system, based on P. pastoris was used to express GNAmaize. Our results show that recombinant GNAmaize is a functional protein. Comparison of the agglutination activity of GNA and GNAmaize towards rabbit erythrocytes revealed that GNAmaize is about 8-fold more potent than GNA. Glycan array experiments revealed that the cytoplasmic GNAmaize interacts with complex N-glycans, in contrast to the vacuolar snowdrop lectin GNA which reacts almost exclusively with high-mannose N-glycans. Insertions in the amino acid sequence before and after putative carbohydrate binding site III at the C-terminus of GNAmaize combined with more subtle structure-sequence differences within all three putative carbohydrate-binding sites may account for such functional differences (Figure 1).

Sequence comparison of GNA and GNAmaize polypeptides revealed 64% sequence similarity. Although both sequences only show 28% sequence identity, the conserved amino acids involve those residues important for three-dimensional conformation of the protein and the formation of the carbohydrate-binding sites. It is interesting to note that GNA-related lectins have also been reported in some fish. A mannose-binding lectin in the skin mucus and intestine of pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes) revealed 29% sequence identity to GNA [11]. Similar to GNAmaize the fish lectin is also synthesized without signal peptide and C-terminal peptide. Studies of the three-dimensional structure of GNA in complex with monosaccharides and/or complex glycans revealed that the GNA monomer possesses 3 carbohydrate binding sites that each can interact with carbohydrates, implying a total of 12 carbohydrate-binding sites for the tetrameric protein [12]. Sequence alignment revealed that the amino acids involved in the recognition of mannose by the three carbohydrate-binding sites of GNA are conserved only in the C-terminal site-III of GNAmaize, whereas carbohydrate-binding sites I and II exhibit significant variation. Notably, site I deviates most significantly from the consensus fingerprint sequence QxDxNxVxYx by carrying a lysine instead of an asparagine at position 34 and an alanine at position 36 instead of a valine, while site II exhibits a cysteine at position 67 instead of a valine (Figure 1).

At present it is not clear whether all mannose-binding sites in GNA share the same specificity. Indeed, one may expect that subtle to significant differences in carbohydrate-specificity and affinity may exist between the three putative carbohydrate-binding sites, given that each is embedded in a unique molecular environment on the GNA scaffold [12]. Our results from the glycan arrays indicate that GNAmaize carries no carbohydrate-binding site with high affinity for high-mannose glycans. This finding is in good agreement with the strongly reduced anti-HIV activity of GNAmaize. The HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein comprises predominantly high-mannose type N-glycans. Agents that interact with such glycans have shown to markedly inhibit HIV entry into its target cells [13-14]. The observation that GNA (preferentially targeting high-mannose type glycans) is substantially more inhibiting to HIV than GNAmaize (preferentially targeting complex-type glycans) confirms the importance of a preferential interaction of the lectins with high-mannose type glycans on HIV gp120 to display pronounced anti-HIV activity.

It should be noted that it has been reported before that gene divergence within certain plant lectin families has resulted in deviations of carbohydrate-binding specificity. Despite the strong similarity at the level of their amino acid sequences and tertiary structures, there is a huge variation between different legume lectins for what concerns their carbohydrate-binding specificities [1, 15-16]. It was shown that a variable loop determines the exact shape of the monosaccharide binding site of legume lectins [16]. Similarly evidence has shown that mannose-binding and galactose-binding jacalin-related lectins are clearly evolutionary related [1, 8, 10].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Consortium for Functional Glycomics funded by the NIGMS GM62116 for the glycan array analysis. We are grateful to Mrs. Romina Termote-Verhalle for excellent technical assistance and to Prof. P.S. Schnable (Iowa State University, USA) for providing the EST clone encoding a GNA homolog from maize (Genbank Accession No. BM351398). The financial support of Ghent University (GOA 01G00805 and GOA 01G001707) and the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO grants G.0201.04 and G.0022.08) to EJMVD is gratefully acknowledged. The research of JB and PP was supported by the Centers of Excellence of the K.U.Leuven (Project no. EF-05/15), the Flemish Concerted Action (GOA) (Project no. 05/19) and the FWO (Project no. G-485-08).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Van Damme EJM, Lannoo N, Peumans WJ. Plant lectins. Adv Botanical Res. 2008;48:107–209. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fouquaert E, Hanton SL, Brandizzi F, Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJM. Localization and topogenesis studies of cytoplasmic and vacuolar homologs of the Galanthus nivalis agglutinin: linking molecular to functional evolution of a mannose-binding domain. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1010–1021. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouquaert E, Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJM. Comm Appl Biol Sci. Vol. 71. Ghent University; 2006. Confocal microscopy confirms the presumed cytoplasmic/nuclear location of plant, fish and fungal orthologs of the Galanthus nivalis agglutinin; pp. 141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blixt O, Head S, Mondala T, Scanlan C, Huflejt ME, Alvarez R, Bryan MC, Fazio F, Calarese D, Stevens J, Razi N, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, van Die I, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Cummings R, Bovin N, Wong CH, Paulson JC. Printed covalent glycan array for ligand profiling of diverse glycan binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17033–17038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibuya N, Goldstein IJ, Van Damme EJM, Peumans WJ. Binding properties of a mannose-specific lectin from the snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) bulb. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Damme EJM, Peumans WJ, Barre A, Rougé P. Plant lectins: a composite of several distinct families of structurally and evolutionary related proteins with diverse biological roles. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1998;17:575–692. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Damme EJM, Allen AK, Peumans WJ. Isolation and characterization of a lectin with exclusive specificity towards mannose from snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) bulbs. FEBS Lett. 1987;215:140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Damme EJM, Barre A, Rougé P, Peumans WJ. Cytoplasmic/nuclear plant lectins: a new story. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsutsui S, Tasaumi S, Suetake H, Suzuki Y. Lectins homologous to those of monocotyledonous plants in the skin mucus and intestine of pufferfish, Fugu rubripes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20882–20889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hester G, Kaku H, Goldstein IJ, Wright CS. Structure of mannose-specific snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) lectin is representative of a new plant lectin family. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:472–479. doi: 10.1038/nsb0695-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balzarini J. Targeting the glycans of glycoproteins: a novel paradigm for antiviral therapy. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:583–597. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bewley CA, Kiyonaka S, Hamachi I. Site-specific discrimination by cyanovirin-N for α-linked trisaccharides comprising the three arms of Man(8) and Man9) J Mol Biol. 2002;322:881–889. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00842-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharon N, Lis H. How proteins bind carbohydrates: lessons from legume lectins. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:6586–6591. doi: 10.1021/jf020190s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loris R, Hamelryck T, Bouckaert J, Wyns L. Legume lectin structure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1383:9–36. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]