Abstract

Strategies for promoting high-efficiency homologous gene replacement have been developed and adopted for many filamentous fungal species. The next generation of analysis requires the ability to manipulate gene expression and to tag genes expressed from their endogenous loci. Here we present a suite of molecular tools that provide versatile solutions for fungal high-throughput functional genomics studies based on locus-specific modification of any target gene. Additionally, case studies illustrate caveats to presumed overexpression constructs. A tunable expression system and different tagging strategies can provide valuable phenotypic information for uncharacterized genes and facilitate the analysis of essential loci, an emerging problem in systematic deletion studies of haploid organisms.

With the proliferation of whole fungal genome sequences, the use of multiple approaches for studying the functions of unknown genes has become imperative (16, 23, 36). Consequently, a major effort was initiated seven years ago to systematically delete each of the ∼10,000 Neurospora crassa genes (11, 12, 15). While this project has progressed efficiently, an anticipated difficulty has been the problem of obtaining useful phenotypic information from strains bearing deletions of essential genes. Furthermore, even for nonessential loci, the phenotype displayed by a knockout is not always fully informative with regard to the function of the gene product. In both cases, with essential genes and novel genes of unknown function, a rich source of additional phenotypic data can be realized from the pseudo-allelic series achieved by regulated expression of the gene products, potentially covering the range from significant under- to overexpression. Thus, regulatable expression of essential genes allows functional analyses and can yield unique biological insights since, for example, overexpression can mimic a gain-of-function allele. In addition, biologically relevant information for otherwise poorly characterized gene products can be systematically accessed by adding fluorescent or immunodetectable tags, in order to perform localization, purification, or interaction studies. Similar strategies, successfully implemented in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, have allowed great advances, setting a new pace for molecular cell biology and functional genomics research (see, e.g., references 3, 25, 28, and 33). Toward these ends, we have developed a versatile tunable expression and tagging strategy in N. crassa, by combining available techniques and proven high-throughput approaches. These include the use of yeast recombinational cloning (YRC) (32), a pipetting robot, recipient strains with high homologous recombination frequency (31), and the library of DNA flanks generated as part of the Neurospora knockout project (11, 13).

One of the main advantages of modifying genes at their endogenous loci is bypassing the problems associated with RIP (repeat induced point mutation) in Neurospora and other fungi (17). During a sexual cross, when two or more copies of a gene are present, the RIP machinery will mutate all copies as part of its whole genome surveillance role (35). This makes the crossing of strains containing ectopically targeted duplicated transgenes undesirable. Hence, introducing a modified copy of a gene at its endogenous locus avoids, in particular, the mutagenic effect of RIP and, in general, facilitates the generation of strains with multiple recombinant loci. Likewise, strains bearing recombinant genes obtained through this method can be easily crossed with other strains, such as a knockout collection, facilitating high-throughput screenings (11).

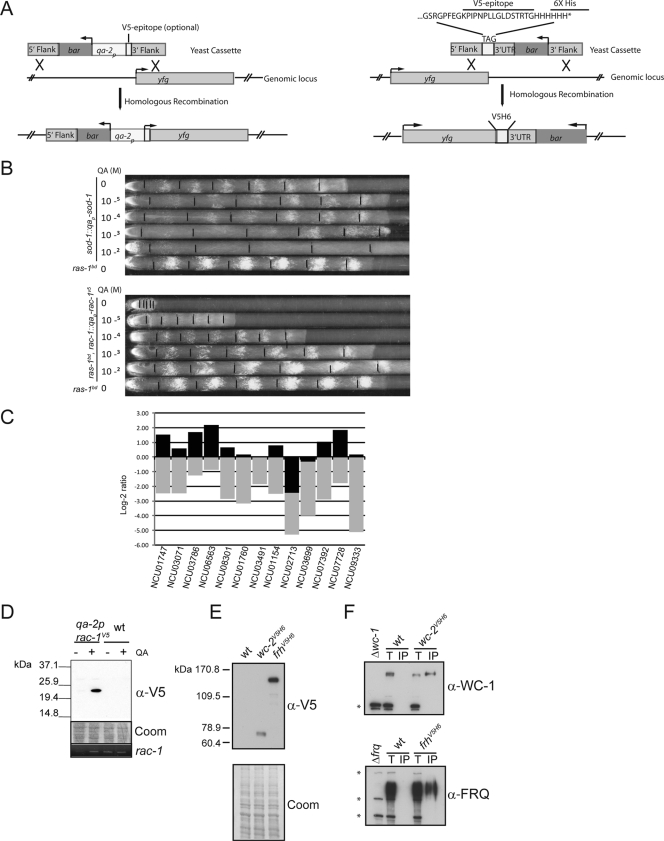

Figure 1A summarizes the overall strategies used for N- or C-terminal modification of different genes of interest. To enable discrete tunable expression, we have developed a strategy to replace the promoter of any gene of interest with a high expression (e.g., tubulin or ccg-1), light (e.g., frq or vvd), or chemical-regulatable (qa-2) promoter (5), by the use of high-throughput gene replacement strains and techniques (11). As a proof of principle, we present here a series of strains created using the well-known qa-2 promoter (2, 18). The oligonucleotides used to generate the “promoter-replacement cassettes” are indicated in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Briefly, either a 1.1-kb or 0.6-kb fragment of the qa-2 promoter was fused to the phosphinothricin resistance gene bar by YRC as previously described (11). The basic bar-qa-2p promoter cassette was targeted to a given locus by the addition of a 5′, ca. 1-kb flank obtained from the Neurospora crassa knockout consortium and a 3′, ca. 1-kb flank, designed so that the open reading frame (ORF) of the gene of interest would be under the control of the inducible promoter (the 3′ end of the 5′ flank is located 0 to 500 bp upstream of the predicted start codon, depending on the gene). Alternatively, the basic cassette can be modified to contain the V5 epitope sequence. In this case, the ORF was fused to the basic cassette starting at position +4, according to the predicted cDNA sequences (Fig. 1A, left panel). The final N- and C-terminal cassettes were assembled by YRC and amplified with high-fidelity, high-yield Taq polymerases as previously described (11), followed by electroporation into Δmus-52::hph strains (31). Strains were homokaryonized by a sexual cross or isolation of microconidia (29). Culture conditions and protein extractions were as previously described (4).

FIG. 1.

Locus-specific tunable expression and N- and C-terminal tagging strategies. (A) General strategy for N- and C-terminal modification of fungal genes using cassettes generated by YRC and PCR. The left panel shows the replacement of an endogenous promoter by the inducible qa-2 promoter, with the option of adding a V5 (or other) epitope to the gene product of interest. The right panel depicts the addition of a tag (V5 epitope six-His) at the C terminal by the same homologous recombination-based strategy. (B) The QA-regulated phenotype of recombinant strains bearing modified sod-1 (upper panel) or rac-1 (lower panel) loci is shown on race tubes containing variable amounts of the inducer QA. (C) RT-PCR analysis of the QA-regulated expression of different loci (NCU numbers are indicated) modified by the addition of the qa-2 promoter in place of the endogenous promoter. Expression values were normalized to actin and are represented as the log2 ratio of noninduced/WT (gray bars) and induced/WT (black bars) expression levels. QA was used at 10−2 M. (D) Immunodetection of epitope-tagged RAC-1. Proteins were extracted from a strain containing a qa-2p-V5-modified rac-1 locus in the absence or presence of QA (for 8 h) and from a ras-1bd strain (indicated as WT) and blotted with anti-V5 (1:1,000). The middle panel shows the Coomassie-stained membrane (loading control), while the lower panel shows an RT-PCR for rac-1 expression, conducted for 25 cycles and with standard conditions. (E) Western blot of ras-1bd (WT) or tagged versions of wc-2V5H6 and frhV5H6 decorated with the anti-V5 antibody. A Coomassie-stained blot is displayed as a loading control. (F) The V5 tag can serve as a common target for coimmunoprecipitation assays. WC-1 interacts with WC-2V5H6 (upper panel) and FRQ interacts with FRHV5H6 (lower panel) when the respective strains are immunoprecipitated with the anti-V5 antibody and Western blots are decorated with either polyclonal anti-WC-1 or anti-FRQ antibodies. However, no protein is detected in WT strains treated similarly. Knockout strains were included as controls for antibody specificity. The asterisks indicate nonspecific bands, while lanes labeled as T and IP correspond to totals and immunoprecipitated (IP) samples, respectively.

Under various concentrations of inducer, both low and high expression-associated phenotypes of a given gene can then be readily analyzed in this system (Fig. 1B and C). For instance, as previously reported, the Neurospora circadian conidiation banding phenotype on race tubes is easily observed in a ras-1bd genetic background or in the presence of high levels of reactive oxygen species (4). The latter can be achieved by the addition of oxidants to the medium or by the deletion of the superoxide dismutase gene (sod-1) (6). To better understand the molecular events regulating conidiation output, a strain was developed where sod-1 expression can be tuned, thus controlling the banding phenotype. In the absence of the inducer quinic acid (QA), the phenotype of qa-2p-sod-1 is similar to that of a Δsod-1 strain (4) and conversely, upon the addition of the inducer, banding is progressively lost in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B, upper panel).

Another example of the utility of this system can be seen using the small GTPase RAC-1, the product of an essential gene for which ascospores bearing gene replacements fail to germinate. In general, small GTPases have been shown to play pivotal roles in controlling growth and development in fungi. RAC-1 has been associated with hyphal morphogenesis (38) and growth (7, 30). As can be seen in the lower panel of Fig. 1B, when a qa-2p-rac-1 strain is examined in the absence of the inducer, growth and morphology are severely affected, a phenotype that is progressively reversed as increasing amounts of inducer are added. More generally, the leakiness of the qa-2 promoter in the absence of QA, here reflected in the weak growth at 0 QA, allows analysis of essential genes at near-knockout levels, achieving dramatic underexpression in some cases (e.g., as in Fig. 1C). Moreover, the addition of an N-terminal tag allows easy detection of the induced protein (Fig. 1D) as well as validation of the regulation by the inducer.

The creation of artificial transgenes, such as those described above, in which expression of a gene is driven by a regulatable promoter is a well-known strategy in fungal research (1, 2). Because such promoters can often be induced several-hundred-fold under appropriate conditions, a common assumption has been that under fully induced conditions, the transgene will mimic an overexpressing strain. However, we have found that this is not always the case and that instead, the dynamic range of inducible expression seems gene specific (Fig. 1C). Various ORFs were placed under the control of the qa-2 promoter, and their overall expression was assayed after growth on cellophane overlying solid race tube medium in the absence or presence of QA (at 0.01 M). Conidia were inoculated at one edge of a square plate in constant light, the plate was transferred to constant darkness after ∼24 h, and tissue corresponding to either 0 to 12 h or 0 to 24 h of growth behind the growth front was collected after 1 to 2 days. RNA was prepared as previously described (10) and assayed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) in an ABI 7500 system. The levels of expression were normalized to actin (which we have found to change minimally) and then compared to the endogenous expression level for each gene in a wild-type (WT) strain grown under the same conditions (Fig. 1C). The results clearly indicate that although there was in all cases induction of gene expression in the presence of QA but not in its absence (5- to 35-fold after normalizing to actin), the overexpression compared to that of the WT ranged from 0- to 5-fold on a gene-specific basis. Whether the different dynamic ranges of expression are due to positional effects, message stability, or some other variable remains to be determined. Additionally, we have observed that QA induction on solid conditions differs from that in liquid media; it tends to be higher in the latter (data not shown). However, an important conclusion is that a significant degree of overexpression compared to WT levels cannot simply be assumed when using a regulatable promoter.

Protein epitope-tagging and reporter fusions are also common tools for biochemistry and cell biology, and similar gene manipulation techniques can be used to facilitate such protein tagging. As opposed to N-terminal tagging, which can result in modification of the endogenous promoter, C-terminal tagging of proteins at their endogenous loci allows gene transcriptional regulation to remain unchanged (Fig. 1A, right panel). As a proof of principle for C-terminal tagging, the V5 epitope six-His tandem tag was fused to 350 bp of the Neurospora actin 3′ untranslated region and the bar gene by YRC. The cassette was targeted to genes of interest by flanking it with a 5′, ca. 1-kb fragment, designed to put the tag in frame with the second to last codon, and a 3′ fragment (usually obtained from the knockout consortium collection) that starts 0 to 500 bp downstream from the stop codon (Fig. 1A, right panel). Cloning and strain generation methodologies were as described above for the N-terminal gene modification strategy. Such epitope tagging allows simplified detection, localization, or purification of any gene product without the time (and budget)-consuming efforts of antibody production. As an example, tagging of Neurospora clock components such as WC-2 (27) and FRH (8) yields functional proteins that can be detected by Western blotting using the same antibody (Fig. 1F). Moreover, the use of a defined epitope allows the comparison of relative levels of different proteins of interest, an estimation that is hard to achieve by immunoblotting using protein-specific antibodies. Proof that these tagged proteins retain function and can still interact with their well-described binding partners, as detected by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 1E), is readily achievable. Moreover, the presence of tandem epitope tags allows efficient protein purification, which can be followed by mass spectrometry to reveal unknown protein-protein interactions. Based on the same methodology presented in Fig. 1A, different regulatable promoters, or diverse tags or reporters, such as hemagglutinin, Myc, yellow fluorescent protein, green fluorescent protein, or luciferase, can be easily added to proteins of interest (data not shown), expanding the horizons of the molecular analysis that can be performed. Moreover, marker-free ku70/80-deficient strains (22) and markers different from bar can be chosen (such as hph or nat), allowing the easy generation of strains with multiple modified loci. Since its first use in N. crassa (31), the implementation of ku70/80 (mus-51/52)-deficient/high homologous recombination frequency strains has quickly spread to different fungal species (9, 14, 19-21, 24, 26, 31, 34, 37). Therefore, we foresee that methods such as the ones summarized herein can be routinely adopted within the fungal community, widening the range for functional genomics studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

L.F.L. was supported by a Pew Latin American Fellowship, and the research was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 grants GM083336 to J.J.L. and J.C.D. and GM34985 and PO1 GM068087 to J.C.D.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 March 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, T. H., and W. E. Timberlake. 1990. Developmental repression of growth and gene expression in Aspergillus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 875405-5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson, B. D., K. A. Johnson, J. J. Loros, and J. Dunlap. 1994. Negative feedback defining a circadian clock: autoregulation of the clock gene frequency. Science 2631578-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahler, J., J. Q. Wu, M. S. Longtine, N. G. Shah, A. McKenzie III, A. B. Steever, A. Wach, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belden, W. J., L. F. Larrondo, A. C. Froehlich, M. Shi, C. H. Chen, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2007. The band mutation in Neurospora crassa is a dominant allele of ras-1 implicating RAS signaling in circadian output. Genes Dev. 211494-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borkovich, K. A., L. A. Alex, O. Yarden, M. Freitag, G. E. Turner, N. D. Read, S. Seiler, D. Bell-Pedersen, J. Paietta, N. Plesofsky, M. Plamann, M. Goodrich-Tanrikulu, U. Schulte, G. Mannhaupt, F. E. Nargang, A. Radford, C. Selitrennikoff, J. E. Galagan, J. C. Dunlap, J. J. Loros, D. Catcheside, H. Inoue, R. Aramayo, M. Polymenis, E. U. Selker, M. S. Sachs, G. A. Marzluf, I. Paulsen, R. Davis, D. J. Ebbole, A. Zelter, E. R. Kalkman, R. O'Rourke, F. Bowring, J. Yeadon, C. Ishii, K. Suzuki, W. Sakai, and R. Pratt. 2004. Lessons from the genome sequence of Neurospora crassa: tracing the path from genomic blueprint to multicellular organism. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 681-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chary, P., D. Dillon, A. L. Schroeder, and D. O. Natvig. 1994. Superoxide dismutase (sod-1) null mutants of Neurospora crassa: oxidative stress sensitivity, spontaneous mutation rate and response to mutagens. Genetics 137723-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, C., and M. B. Dickman. 2004. Dominant active Rac and dominant negative Rac revert the dominant active Ras phenotype in Colletotrichum trifolii by distinct signalling pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 511493-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, P., Q. He, L. Wang, and Y. Liu. 2005. Regulation of the Neurospora circadian clock by an RNA helicase. Genes Dev. 19234-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choquer, M., G. Robin, P. Le Pecheur, C. Giraud, C. Levis, and M. Viaud. 2008. Ku70 or Ku80 deficiencies in the fungus Botrytis cinerea facilitate targeting of genes that are hard to knock out in a wild-type context. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colot, H. V., J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2005. Temperature-modulated alternative splicing and promoter use in the circadian clock gene frequency. Mol. Biol. Cell 165563-5571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colot, H. V., G. Park, G. E. Turner, C. Ringelberg, C. M. Crew, L. Litvinkova, R. L. Weiss, K. A. Borkovich, and J. C. Dunlap. 2006. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10310352-10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunlap, J. C., K. A. Borkovich, M. R. Henn, G. E. Turner, M. S. Sachs, N. L. Glass, K. McCluskey, M. Plamann, J. E. Galagan, B. W. Birren, R. L. Weiss, J. P. Townsend, J. J. Loros, M. A. Nelson, R. Lambreghts, H. V. Colot, G. Park, P. Collopy, C. Ringelberg, C. Crew, L. Litvinkova, D. DeCaprio, H. M. Hood, S. Curilla, M. Shi, M. Crawford, M. Koerhsen, P. Montgomery, L. Larson, M. Pearson, T. Kasuga, C. Tian, M. Basturkmen, L. Altamirano, and J. Xu. 2007. Enabling a community to dissect an organism: overview of the Neurospora functional genomics project. Adv. Genet. 5749-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunlap, J. C., J. J. Loros, H. V. Colot, A. Mehra, W. J. Belden, M. Shi, C. I. Hong, L. F. Larrondo, C. L. Baker, C. H. Chen, C. Schwerdtfeger, P. D. Collopy, J. J. Gamsby, and R. Lambreghts. 2007. A circadian clock in Neurospora: how genes and proteins cooperate to produce a sustained, entrainable, and compensated biological oscillator with a period of about a day. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 7257-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Khoury, R., C. H. Sellem, E. Coppin, A. Boivin, M. F. Maas, R. Debuchy, and A. Sainsard-Chanet. 2008. Gene deletion and allelic replacement in the filamentous fungus Podospora anserina. Curr. Genet. 53249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galagan, J. E., S. E. Calvo, K. A. Borkovich, E. U. Selker, N. D. Read, D. Jaffe, W. FitzHugh, L. J. Ma, S. Smirnov, S. Purcell, B. Rehman, T. Elkins, R. Engels, S. Wang, C. B. Nielsen, J. Butler, M. Endrizzi, D. Qui, P. Ianakiev, D. Bell-Pedersen, M. A. Nelson, M. Werner-Washburne, C. P. Selitrennikoff, J. A. Kinsey, E. L. Braun, A. Zelter, U. Schulte, G. O. Kothe, G. Jedd, W. Mewes, C. Staben, E. Marcotte, D. Greenberg, A. Roy, K. Foley, J. Naylor, N. Stange-Thomann, R. Barrett, S. Gnerre, M. Kamal, M. Kamvysselis, E. Mauceli, C. Bielke, S. Rudd, D. Frishman, S. Krystofova, C. Rasmussen, R. L. Metzenberg, D. D. Perkins, S. Kroken, C. Cogoni, G. Macino, D. Catcheside, W. Li, R. J. Pratt, S. A. Osmani, C. P. DeSouza, L. Glass, M. J. Orbach, J. A. Berglund, R. Voelker, O. Yarden, M. Plamann, S. Seiler, J. Dunlap, A. Radford, R. Aramayo, D. O. Natvig, L. A. Alex, G. Mannhaupt, D. J. Ebbole, M. Freitag, I. Paulsen, M. S. Sachs, E. S. Lander, C. Nusbaum, and B. Birren. 2003. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 422859-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galagan, J. E., M. R. Henn, L. J. Ma, C. A. Cuomo, and B. Birren. 2005. Genomics of the fungal kingdom: insights into eukaryotic biology. Genome Res. 151620-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galagan, J. E., and E. U. Selker. 2004. RIP: the evolutionary cost of genome defense. Trends Genet. 20417-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giles, N. H., M. E. Case, J. Baum, R. Geever, L. Huiet, V. Patel, and B. Tyler. 1985. Gene organization and regulation in the qa (quinic acid) gene cluster of Neurospora crassa. Microbiol. Rev. 49338-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goins, C. L., K. J. Gerik, and J. K. Lodge. 2006. Improvements to gene deletion in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans: absence of Ku proteins increases homologous recombination, and co-transformation of independent DNA molecules allows rapid complementation of deletion phenotypes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43531-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guangtao, Z., L. Hartl, A. Schuster, S. Polak, M. Schmoll, T. Wang, V. Seidl, and B. Seiboth. 2009. Gene targeting in a nonhomologous end joining deficient Hypocrea jecorina. J. Biotechnol. 139146-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haarmann, T., N. Lorenz, and P. Tudzynski. 2008. Use of a nonhomologous end joining deficient strain (Deltaku70) of the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea for identification of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene involved in ergotamine biosynthesis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 4535-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He, Q., J. Cha, H. C. Lee, Y. Yang, and Y. Liu. 2006. CKI and CKII mediate the FREQUENCY-dependent phosphorylation of the WHITE COLLAR complex to close the Neurospora circadian negative feedback loop. Genes Dev. 202552-2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedeler, C., H. M. Wong, M. J. Cornell, I. Alam, D. M. Soanes, M. Rattray, S. J. Hubbard, N. J. Talbot, S. G. Oliver, and N. W. Paton. 2007. e-Fungi: a data resource for comparative analysis of fungal genomes. BMC Genomics 8426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krappmann, S., C. Sasse, and G. H. Braus. 2006. Gene targeting in Aspergillus fumigatus by homologous recombination is facilitated in a nonhomologous end-joining-deficient genetic background. Eukaryot. Cell 5212-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar, A., S. Agarwal, J. A. Heyman, S. Matson, M. Heidtman, S. Piccirillo, L. Umansky, A. Drawid, R. Jansen, Y. Liu, K. H. Cheung, P. Miller, M. Gerstein, G. S. Roeder, and M. Snyder. 2002. Subcellular localization of the yeast proteome. Genes Dev. 16707-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan, X., Z. Yao, Y. Zhou, J. Shang, H. Lin, D. L. Nuss, and B. Chen. 2008. Deletion of the cpku80 gene in the chestnut blight fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica, enhances gene disruption efficiency. Curr. Genet. 5359-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linden, H., and G. Macino. 1997. White collar 2, a partner in blue-light signal transduction, controlling expression of light-regulated genes in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J. 1698-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maheshwari, R. 1991. Microcycle conidiation and its genetic basis in Neurospora crassa. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1372103-2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahlert, M., L. Leveleki, A. Hlubek, B. Sandrock, and M. Bolker. 2006. Rac1 and Cdc42 regulate hyphal growth and cytokinesis in the dimorphic fungus Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 59567-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ninomiya, Y., K. Suzuki, C. Ishii, and H. Inoue. 2004. Highly efficient gene replacements in Neurospora strains deficient for nonhomologous end-joining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10112248-12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oldenburg, K. R., K. T. Vo, S. Michaelis, and C. Paddon. 1997. Recombination-mediated PCR-directed plasmid construction in vivo in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 25451-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petracek, M. E., and M. S. Longtine. 2002. PCR-based engineering of yeast genome. Methods Enzymol. 350445-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poggeler, S., and U. Kuck. 2006. Highly efficient generation of signal transduction knockout mutants using a fungal strain deficient in the mammalian ku70 ortholog. Gene 3781-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer, M. J., and E. U. Selker. 1995. Genetic and epigenetic inactivation of repetitive sequences in Neurospora crassa: RIP, DNA methylation, and quelling. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 197165-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soanes, D. M., T. A. Richards, and N. J. Talbot. 2007. Insights from sequencing fungal and oomycete genomes: what can we learn about plant disease and the evolution of pathogenicity? Plant Cell 193318-3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi, T., T. Masuda, and Y. Koyama. 2006. Enhanced gene targeting frequency in ku70 and ku80 disruption mutants of Aspergillus sojae and Aspergillus oryzae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 275460-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Virag, A., M. P. Lee, H. Si, and S. D. Harris. 2007. Regulation of hyphal morphogenesis by cdc42 and rac1 homologues in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 661579-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.