Abstract

The main objective of this study was to determine how the size, structure, and activity of the nitrate reducer community were affected by adoption of a conservative tillage system as an alternative to conventional tillage. The experimental field, established in Madagascar in 1991, consists of plots subjected to conventional tillage or direct-seeding mulch-based cropping systems (DM), both amended with three different fertilization regimes. Comparisons of size, structure, and activity of the nitrate reducer community in samples collected from the top layer in 2005 and 2006 revealed that all characteristics of this functional community were affected by the tillage system, with increased nitrate reduction activity and numbers of nitrate reducers under DM. Nitrate reduction activity was also stimulated by combined organic and mineral fertilization but not by organic fertilization alone. In contrast, both negative and positive effects of combined organic and mineral fertilization on the size of the nitrate reducer community were observed. The size of the nitrate reducer community was a significant predictor of the nitrate reduction rates except in one treatment, which highlighted the inherent complexities in understanding the relationships the between size, diversity, and structure of functional microbial communities along environmental gradients.

The transition from intensive tillage to various forms of conservation tillage began more than 50 years ago with the development of herbicides which have replaced mechanical cultivation. Since then, the principles of no-till cropping have been extensively adopted by farmers worldwide. This cropping system, also known as direct seeding, mimics natural systems by leaving the soil mostly undisturbed and permanently covered with crop residues or living plants. The benefits of reducing tillage in sustainable agriculture are now well recognized for various environmental and economic reasons (14). Leaving all residues of the previous crop on the soil surface protects against evaporative water loss, wind erosion, and surface water runoff. Concomitant with reduced erosion, no-till cropping can also result in enhanced soil carbon storage in the topsoil layer, with estimated carbon sequestration rates of 30 to 60 g C m2 year−1 (27, 50). In turn, these changes in soil organic matter and soil structure under a no-till cropping system can affect microbial communities (20). Thus, the microbial biomass is most often higher in no-till systems than in conventional tillage systems (11, 26). Analysis of the structure or activity of soil microbial communities has also revealed significant differences between conventional tillage and minimal tillage or no-tillage systems (25, 29). However, although the effect of tillage practices on the total soil microbial community in relation to soil organic matter management has frequently been investigated, knowledge of the changes in N-cycling microbial communities induced by no-till management is limited and is mainly focused on N process rates (3, 11, 32).

The aim of this work was to determine how conversion from conventional tillage to no-till affects microorganisms involved in the N cycle. For this purpose, we used the nitrate reducing community as a model functional guild (40). Prokaryote nitrate reducers constitute a wide taxonomic group with a shared ability to produce energy from the dissimilatory reduction of nitrate to nitrite, the first step of denitrification and of the dissimilatory processes of reduction of nitrate to ammonium (39). Nitrate reduction by denitrification is of great importance, since the resulting nitrite is then reduced to N2O or N2 gases, which can lead to considerable nitrogen losses in agriculture and emissions of the N2O greenhouse gas (4, 13). We hypothesized that higher C and N contents in the no-till system will result in increased nitrate reduction rates and nitrate reducer abundance combined with shifts in the community composition. Relationships between the size, activity, and structure of the nitrate reducer community in the studied cropping systems were also investigated. The structure and size of the nitrate reducer community were assessed by fingerprinting and real-time PCR using the narG and napA genes, encoding the membrane-bound and periplasmic nitrate reductases, respectively, as molecular markers (40, 41). The potential activity of the nitrate reducing community was determined by colorimetric measurement of the nitrite produced during nitrate reduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental field and sampling.

This study was conducted in the experimental station of Tany sy Fampandrosoan, district of Bemasoandro (19°46′45" south, 47°06′25" east), Antsirabe region, in the highlands of Madagascar. This area has a cold tropical high-altitude climate with 10 to 20 days of frost annually and a mean temperature of 16.9°C. The site is at an altitude of 1,600 m above sea level with an annual average rainfall of 1,450 mm. The soil is described as an andic dystrustept, and the physical properties were as follows: clay, 61.90%; bulk density, 0.76 g cm−3; pH (H2O), 5.72; CEC, 17.32 cmol kg−1 soil). The experiment was set up in 1991, with annual soybean (Glycine max L.)-rice (Oriza sativa) rotations and conventional tillage or direct-seeding mulch-based cropping (DM) systems. DM is based on the absence of soil tillage, maintenance of a mulch of crop residues at all times, direct seeding into crop residues, and use of suitable crop successions. Both DM and conventional tillage systems were either not fertilized (F0), fertilized with farmyard manure at 5 tons ha−1 year−1 (F1), or fertilized with farmyard manure at 5 tons ha−1 year−1 combined with mineral fertilizer (F2), which resulted in six management regimes. Mineral fertilizers were used at the recommended rates of 30 N, 30 P, and 40 K kg ha−1 year−1 for soybeans and 70 N, 30 P, and 40 K kg ha−1 year−1 for rice. The direct-seeding mulch-based cropping system consisted of sowing in a mulch of crop residue with no tillage. The experimental site consists of three randomized blocks, each block containing six plots (3 by 5 m), corresponding to the six management regimes. Soil was collected from the 0- to 5-cm horizon on 28 January 2005 and on 12 February 2006, air-dried, and sieved to <2 mm. In each of the 18 plots, we collected five soil cores at three different locations, which were pooled to obtain three composite bulk soil samples per plot and nine samples per treatment. In total, we therefore collected 270 soil cores in the experimental field on each sampling date, and 54 composite soil samples were used for the subsequent analysis.

Soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, nitrate, and ammonium.

Total organic carbon (C) and total nitrogen (N) were determined by dry combustion in a CHN autoanalyzer (EA1112 Thermofinnigan Series) using dried (105°C, 48 h) and ground soil samples (<200 μm). Results were expressed in mg C g−1 soil. Nitrate and ammonium concentrations were determined by colorimetry using a Technicon autoanalyzer (Technicon II; Bran-Luebbe, Plaisir, France) after extraction from 10 g of soil with 100 ml of 1 M KCl according to the method of Bremner (5).

Measurement of potential nitrate reductase activity.

Potential nitrate reductase activity was determined by soil anaerobic incubation, following the slightly modified protocol of Kandeler (31). The method involved determination of the NO2−-N production after addition of nitrate as a substrate and 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) as an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation that interfered with electron transfer but allowed nitrate reduction to continue. Substrate as well as DNP inhibitor concentrations were optimized in preexperiments. In detail, for each of the three replicates from each plot, soil (0.2 g) was weighed and divided into four replicates and then was incubated in a total volume of 1 ml containing 1 mM potassium nitrate. The optimum inhibitory concentration of DNP (0.9 mM) was then added to inhibit nitrite reduction. After 24 h of incubation at 28°C, the soil mixture was extracted with 4 M KCl and centrifuged for 1 min at 13,000 × g. The accumulated nitrite in the supernatant was determined by colorimetric reaction at 520 nm using a reagent composed of phosphoric acid (1% [vol/vol]), N1-naphthyl ethylenediamine dichloride (2 g liter−1), and sulfanilamide (40 g liter−1).

Soil DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from the three composite soil samples from each plot according to the Ultra Clean Soil DNA kit protocol (reference 12800-100; Ozyme, Mo Bio, France). The 54 DNA extracts for each sampling date were then quantified by spectrophotometry at 260 nm using a biophotometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Genetic structure analysis of the nitrate reducer community.

The structure of the nitrate reducer community was assessed using the narG and napA genes, encoding the membrane-bound and periplasmic nitrate reductase, respectively, as molecular markers. The three DNA extracts from triplicate plots were pooled, resulting for each sampling date in a total of 18 DNA samples, which were used as a PCR template. The narG and napA genes were amplified using the narG1960F (5′-TAYGTSGGSCARGARAA-3′) and narG2650R (5′-TTYTCRTACCABGTBGC-3′) primers (45) and the napV67m (5′-AAYATGGCVGARATGCACCC-3′) and napV17m (5′-GRTTRAARCCCATSGTCCA-3′) (28) primers using previously described PCR conditions (28, 45). PCRs were carried out in a 50-μl mixture containing 1.5 mM MgCl2 buffer, 200 mM of each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 5 mM of each primer, and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Qbiogene, France). At least three independent PCRs were performed, and the PCR products were then pooled for each replicate to minimize the effect of PCR bias. PCR products were purified using the MiniElute gel extraction kit (Qiagen, France). Purified narG and napA PCR products were digested with the AluI restriction enzyme at 37°C for 4 h as described previously (28, 45). The narG and napA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) fingerprints were obtained after separation by electrophoresis on a native 6% acrylamide-bisacrylamide (29:1) gel for 11 h at 5 mA. DNA staining was done using SYBR green, and the resulting fluorescence was scanned with a PhosphorImager (Storm 860; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Quantitative PCR assays for narG and napA gene copy enumeration.

The real-time PCR assay was carried out in a 20 μl reaction volume containing SYBR green PCR master mix (Absolute QPCR SYBR green ROX; ABgene, France), 1 μM of each primer, 100 ng of T4 gene 32 (QBiogene, France), and 12.5 ng of DNA. Fragments of the narG and napA genes were amplified using the previously described primers and thermal cycling conditions (8). Thermal cycling, fluorescent data collection, and data analysis were carried out with the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two independent quantitative PCR assays were performed for each gene and for the three DNA extracts from each plot. Two to three no-template controls were run for each quantitative PCR assay. Serial dilution of linearized plasmids containing the narG and napA genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 were used to generate standard curves (8). The copy number of standard DNA genes was calculated using the following formula: X g/μl DNA/[plasmid length (bp) × 660] × 6.022 × 1023 = Y molecules/μl, where X is the concentration of linearized plasmid.

All narG and napA assays were run with DNA from P. aeruginosa PAO1 containing one copy of each of these two genes as an external standard. The specificity of the assay was verified by melting-curve analysis and gel electrophoresis. Tests for the potential presence of PCR inhibitors in DNA extracted from soil were performed by diluting soil DNA extracts and spiking soil DNA extracts with a known amount of standard DNA prior to quantitative PCR. In all cases, no inhibition was detected.

Statistical analysis.

When required, data were normalized by log or Box-Cox transformation. A Student t test was used to analyze the effects of the tillage system and fertilization regime on the size and activity of the nitrate reducer community. The narG and napA fingerprint gels were analyzed using the TotalLab TL120 software (Nonlinear Dynamics Ltd.). This software converted the fluorescence of DNA fragments of different sizes into electropherograms. Data obtained from the software were converted into a table summarizing the band presence and intensity. Hierarchical cluster analysis was based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices of the fingerprint data using the XLSTAT software program (Addinsoft SARL, France). Pearson correlation analyses were performed to test the relationships between gene copy numbers and nitrate reduction rates. Correlations with the nitrate reducer community structure were analyzed by transforming the values of the nitrate reduction rates and narG and napA gene densities to dissimilarity matrices using Euclidean distance measures and comparing them to narG and napA community structure dissimilarity matrices obtained by Bray-Curtis distance measure using Mantel's test, which is a statistical test of correlation between two matrices (35). The tests were performed using Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient and 1,000 permutations for each test.

RESULTS

Effect of tillage system and fertilization regime on soil carbon and nitrogen contents.

The tillage system significantly influenced soil C and N, since contents were higher under DM than under conventional tillage regardless of the fertilization regime or sampling year (Table 1). Similarly, higher nitrate and ammonium concentrations were observed for DM than for conventional tillage in the F0 and F1 plots (Table 1). The fertilization regime also had a significant impact on soil C and N contents, which were modulated by both the sampling year and the tillage system (P < 0.03). In general, the C and N contents followed the gradient of fertilization, with higher contents in plots amended with farmyard manure combined with mineral fertilizers (F2) than in plots amended with farmyard manure alone (F1) or without fertilizers (F0). However, in 2005, the N content was not affected by the fertilization regime in the DM system.

TABLE 1.

Carbon and nitrogen contents in conventional-tillage and DM systems subjected to three different fertilization regimesa

| Tillage system | Fertilization regime | Carbon or nitrogen content in indicated yr

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon (%)

|

Nitrogen (%)

|

Nitrate (mg N g−1 soil)

|

Ammonium (mg N g−1 soil)

|

||||||

| 2005 | 2006 | 2005 | 2006 | 2005 | 2006 | 2005 | 2006 | ||

| Conventional | F0 | 2.3 (0.3) a | 2.5 (0.3) a | 0.16 (0.02) a | 0.18 (0.03) a | 6.8 (1.0) a | ND | 6.2 (2.0) a | ND |

| F1 | 2.4 (0.2) ab | 2.7 (0.2) a | 0.17 (0.02) ab | 0.20 (0.02) a | 4.2 (1.0) b | ND | 8.5 (2.4) a | ND | |

| F2 | 2.6 (0.3) b | 2.9 (0.2) b | 0.19 (0.03) b | 0.23 (0.02) b | 4.0 (1.0) b | ND | 15.2 (2.7) b | ND | |

| Direct-seeding mulch based | F0 | 3.5 (0.3) c | 3.5 (0.3) c | 0.25 (0.03) c | 0.28 (0.03) c | 9.9 (1.9) c | ND | 14.2 (2.5) b | ND |

| F1 | 3.7 (0.4) cd | 3.9 (0.3) d | 0.25 (0.03) c | 0.31 (0.03) c | 6.3 (2.5) a | ND | 13.1 (2.6) b | ND | |

| F2 | 3.9 (0.5) d | 4.5 (0.5) e | 0.25 (0.05) c | 0.37 (0.05) d | 5.2 (3.0) ab | ND | 15.3 (3.4) b | ND | |

Within each year, means followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P values of <0.05. ND, not determined.

Effect of tillage system and fertilization regime on nitrate reduction activity.

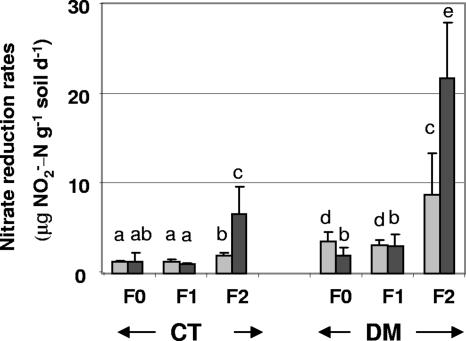

The potential nitrate reduction activity, based on nitrite accumulation, ranged from 0.99 to 21 μg N-NO2− g−1 dry soil day−1 and therefore exhibited high variation depending on the sampling year and tillage and fertilization regimes (Fig. 1). The potential nitrate reduction activity was between 2.5 and 4.4 times higher in DM than in the conventional tillage system for both years and for all fertilization regimes, except the no-fertilization treatment in 2006 (Fig. 1). A significant effect of the fertilization regime on potential nitrate reduction activity was also observed, with higher rates in the farmyard manure combined with mineral fertilizer treatment (F2) than with the other fertilization regimes (Fig. 1). This stimulating effect of combined organic and mineral fertilization was stronger in 2006 than in 2005, the rates being 2.5 times and 3.4 times higher in 2006 under the DM and conventional tillage systems, respectively (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Potential nitrate reduction rates in direct mulch seeding (DM) and conventional tillage (CT) systems with F0, F1, or F2 in 2005 (light gray bars) or 2006 (dark gray bars). The same letters above the bars (mean ± standard deviation; n = 9) indicate that treatments are not significantly different according to the t test (P < 0.05) d−1, per day.

Structure of nitrate reducer community in relation to the agricultural management regime.

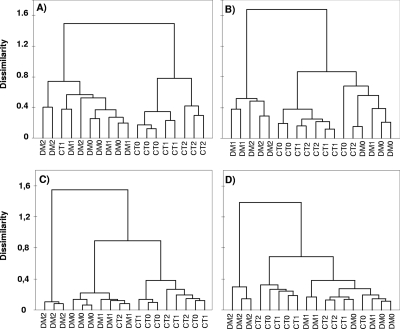

In order to reduce the impact of gel-to-gel variations on gel analysis, all samples from the same sampling date were run on the same gel. Twelve to 27 bands were used for analysis of the narG or napA RFLP gels (data not shown). Hierarchical cluster analysis of both narG and napA RFLP fingerprints showed that most samples from DM separated from those from the conventional tillage system (Fig. 2) but with weak differences between the two types of agricultural practices (with total variance explained by principal component analysis ranging from 20.5 to 47.6%; data not shown). The fertilization regime had the strongest effect on the napA community structure, as shown by the branching of the F2 samples from DM (Fig. 2C and D). However, in all the other cases, the effect of the fertilization was very weak or not significant.

FIG. 2.

Structure of the nitrate reducer community under the DM (open circles) or conventional tillage system (CT) (closed circles) with no fertilization (0), fertilization with farmyard manure (1), or fertilization with farmyard manure combined with mineral fertilizer (2). Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis of the narG PCR-RFLP fingerprints in 2005 (A) or in 2006 (B) or of the napA PCR-RFLP fingerprints in 2005 (C) or in 2006 (D) is shown.

Size of nitrate reducer community in relation to the agricultural management regime.

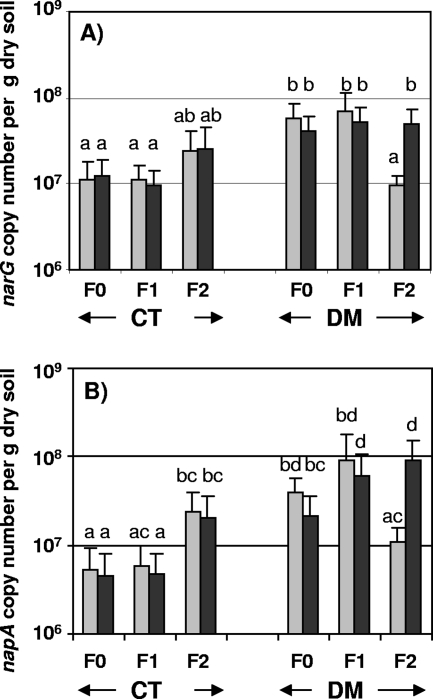

The size of the nitrate reducer community, estimated by real-time PCR quantification of the narG and napA gene copies, is presented in Fig. 3. The average gene copy number for narG was slightly higher than that for napA, with densities between 0.76 × 103 and 11.7 × 103 copies per ng of extracted DNA, which corresponds to 0.7 × 108 and 9.0 × 108 copies per gram of dry soil. The copy numbers of narG and napA per gram of soil were significantly higher in DM than in the conventional tillage system for all fertilization regimes and both years except for F2 in 2005, where no significant differences were observed. The impact of the fertilization regime on gene copy number was dependent on the tillage system and sampling year and also on the gene targeted (Fig. 3). Thus, the fertilization regime had no effect on narG density except in 2005 under DM, when the narG gene copy numbers per gram of soil were significantly lower with F2 than with F0 or F1. The same decrease of napA density was observed with F2 under DM in 2005. On the contrary, a significant stimulatory effect of the F2 fertilization regime on napA density was observed for both years in the conventional tillage system and in the DM in 2006 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Size of the nitrate reducer community under the direct mulch seeding (DM) or conventional tillage system (CT) with F0, F1, or F2 in 2005 (light gray bars) or 2006 (dark gray bars), estimated by quantitative PCR of the narG (A) or napA (B) gene. Bars indicate gene copy numbers expressed per gram of dry soil. The same letters above the bars (mean ± standard deviation; n = 9) indicate that treatments are not significantly different according to the t test (P < 0.05).

Relationships between activity, size, and composition of nitrate reducer community in different cropping systems.

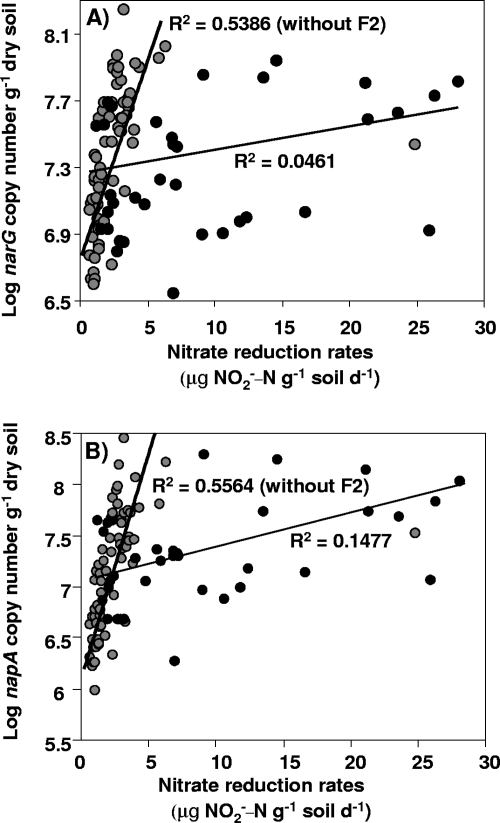

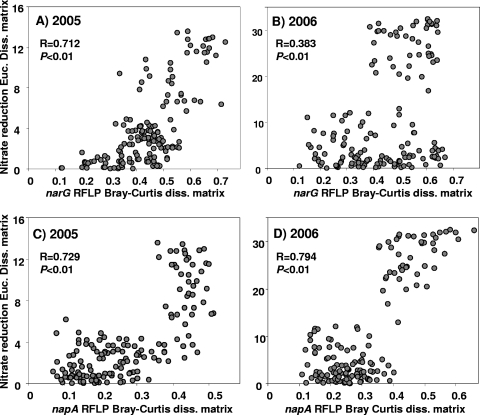

Weak or no correlation was were observed between narG (r2 = 0.046), napA (r2 = 0.148; P < 0.01), or narG plus napA (r2 = 0.097; P < 0.05) gene copy numbers and potential nitrate reduction activity (Fig. 4). However, when the data were analyzed without the F2 plots, significant stronger correlations between activity and the size of the nitrate reducer community were found for narG (r2 = 0.539; P < 0.001), napA (r2 = 0.556; P < 0.001), and narG plus napA (r2 = 0.555; P < 0.001) gene copy numbers (Fig. 4). Mantel tests revealed that activity of the nitrate reducer community was also significantly related to the structure of this community, which was due mainly to the larger differences observed in the F2 treatment (Fig. 5). Thus, differences between the napA and narG community composition were correlated with differences in potential nitrate reduction activity, with the highest correlations of R values of 0.729 and 0.794 between napA community composition and potential nitrate reduction activity being observed in 2005 and 2006, respectively (Fig. 5). Differences in nitrate reducer community composition were also related to differences in nitrate reducer community size (P < 0.05), except for narG in 2005 (R = 0.063). Thus, correlations of R values of 0.212 and 0.34 were observed for differences between napA community composition and napA gene copy numbers in 2005 and 2006, respectively, and an R value of 0.412 for differences between narG community composition and narG gene copy numbers in 2006 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Relationships between size and activity of the nitrate reducer community. Pearson's correlation between the narG gene copy number per gram of dry soil (A) or the napA gene copy number per gram of dry soil (B) and potential nitrate reduction rates with or without data from the F2 fertilization regime is shown (black circles represent data from F2). d−1, per day.

FIG. 5.

Correlation between nitrate reducer community structure and activity dissimilarity matrices. narG RFLP fingerprints and potential nitrate reduction rates in 2005 (A), narG RFLP fingerprints and potential nitrate reduction rates in 2006 (B), napA RFLP fingerprints and potential nitrate reduction rates in 2005 (C), and napA RFLP fingerprints and potential nitrate reduction rates in 2006 (D) are analyzed. Euc. Diss., Euclidean distance.

DISCUSSION

Leaving soils mostly undisturbed and covered with crop residues is known to improve the soil nutrient status in the top layer (14). Accordingly, a significant increase in C and N contents was observed under DM compared to results with the conventional cropping system in this study (Table 1). This increase of C and N under DM was concomitant with a significant stimulation (P < 0.001) of the potential nitrate reduction activity in DM both in 2005 and 2006, with rates in the same range as those previously reported for a grassland soil (18). A higher potential denitrification activity under DM than under the conventional cropping system had also been observed in the same experimental field (E. Baudoin, L. Philippot, D. Chèneby, L. Chapuis-Lardy, N. Fromin, D. Bru, B. Rabary, and A. Brauman, submitted for publication). That nitrate reduction and denitrification are correlated with C content in soil is well known and has been demonstrated in several studies (6). However, no correlation was observed between nitrate concentrations and potential nitrate reduction rates. In our field experiment, it cannot be excluded that factors other than the higher C and N contents also contributed to the promotion of nitrate reduction activity in DM compared to results in the conventional tillage system. Indeed, a previous study reported a higher soil water content in the DM than in the conventional tillage system at the same experimental site (45a). Investigations of the effect of tillage on N-cycle microbial processes have mainly focused on denitrification or nitrification. Although it was shown that a tillage event could temporally increase denitrification rates for a few days (10, 30), it is apparent from most values cited in the literature that no-till soils, as compared to conventionally tilled soils, stimulate denitrification rates in the long term (1, 24, 37, 49), which is in agreement with our results. We found that the fertilization regime also had an effect on potential nitrate reduction, with the rates being significantly increased in plots fertilized with farmyard manure combined with mineral fertilizer. This increase was stronger in DM than in the conventional tillage system (Fig. 1), which suggests that nitrate reduction was more stimulated by the addition of combined fertilizer when soil aggregation and the nitrate reducer community were not affected by tillage. In contrast, addition of farmyard manure alone had no effect on potential nitrate reduction activity, whereas manure has been shown to promote denitrification activity (17, 23, 36, 38). Altogether, our results on nitrate reduction activity are in agreement with reports of previous studies with increases of denitrification activity in reduced tillage systems or in response to higher fertilization levels (reviewed in reference 44).

Analysis of the nitrate reducer community structure using the narG and napA genes encoding the catalytic subunits of the two types of respiratory nitrate reductases as molecular markers revealed small differences between the DM and conventional cropping systems (Fig. 3). Agricultural practices, such as tillage or fertilization, have already been reported to be important factors driving the structure of soil microbial communities (10, 15, 20, 21). Salles et al. (48) even found that fertilization and tillage were more effective than the agricultural management regime in changing the Burkholderia community structure. Studies of the effect of tillage practices on the structure of microbial communities involved in N cycling are rare (9). However, more information is available about how the structure of these communities can be affect by the fertilization regime. Thus, slight to important modifications in the structure of the denitrifier community in response to fertilizer addition have been reported, depending on the type of fertilizer and also on the time scale of the field experiment (2, 17, 23, 51; reviewed in reference 44). We found that fertilization with farmyard manure combined with mineral fertilizer had the strongest effect on the napA community structure (Fig. 2C and D), while tillage practice was the primary driver of the narG community structure (Fig. 2A and B). This suggests that different microbial populations are carrying the narG and napA genes and that these populations are differentially affected by the studied agricultural practices. However, the differences observed in this study were minor, and after 15 years, neither tillage practices nor fertilization regimes caused important shifts in the composition of the nitrate reducer community.

The size of the nitrate reducer community in the different cropping systems was estimated by quantifying the narG and napA genes by real-time PCR. Because it is likely that all DNA was not successfully extracted from the soil samples, the gene copy numbers were calculated both as nanograms of extracted DNA (see Fig S1 in the supplemental material) and per gram of soil (Fig. 3). However, since potential nitrate reductase activities are expressed per gram of soil, only the gene copy numbers per gram of soil were used for further analyses of the relationships between the size, structure, and activity of the nitrate reducer community. Besides, while most nitrate reducing bacteria possess either narG or napA, a significant proportion of nitrate reducing bacteria also possess both narG and napA (39, 47), which makes it difficult to convert the narG and napA gene copy numbers into nitrate reducer cell numbers. Therefore, we used the narG and napA real-time PCR data separately but also the sum of the narG and napA gene copy numbers to investigate relationships between the size, structure, and activity of the nitrate reducer community. The narG and napA gene copy numbers in the upland soil of Madagascar were similar to densities previously found in agricultural soils (8, 42). Studies investigating the effect of tillage on the sizes of microbial communities were based mostly on microbial biomass measurements and reported increases in microbial biomass after the change from conventional to reduced or minimum tillage (12, 16, 19, 20). However, later studies demonstrated that this stimulating effect of reduced tillage was limited to the topsoil, with no consistent effect in the 2.5- to 20-cm (52) or 20- to 30-cm layer (33). Reduced tillage on its own was not responsible for enhanced microbial biomass, but rather the combination of reduced tillage and residue amendment was responsible. Stimulatory effects were attributed mainly to increased soil moisture and aeration, cooler temperature, and a higher carbon content in surface soil (20). A few studies also reported that cultivable soil denitrifier populations tended to increase with less tillage (7, 22). Our study showing significantly higher narG and napA gene copy numbers in the 0- to 5-cm layer under DM than under conventional tillage (P < 0.001) confirmed these findings. Addition of farmyard manure alone (F1) had no impact on either the narG or napA gene copy numbers, whatever the sampling year, whereas a combined farmyard manure and mineral fertilizer amendment (F2) significantly affected the gene copy numbers either positively or negatively (Fig. 4). Further investigations are required to understand how combined organic and mineral fertilization can sometimes decrease the numbers of nitrate reducers.

Functional communities involved in N cycling provide good models in microbial ecology for studying the role of the size and structure of microbial communities in corresponding process rates and ecosystem functioning (34, 43). To analyze the relationships between the size and structure of the nitrate reducer community and nitrate reduction activity, we performed Mantel tests of correlation between dissimilarity matrices and calculated Pearson correlations. Since nitrate reduction is a facultative respiratory process, the presence of nitrate and carbon and the absence of oxygen are the factors primarily regulating the nitrate reduction activity. Nevertheless, when conditions are favorable to nitrate reduction, we can hypothesize that the nitrate reduction activity is related to the size of the nitrate reducer community. In this study, a significant correlation was observed between the size and the activity of the nitrate reducer community but only when values from the F2 treatment were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 4). The slope of the regression lines indicates that a 10-fold increase in the number of nitrate reduction genes corresponded to a threefold increase in nitrate reduction rates. This suggests that only a fraction of the nitrate reducers were present in niches where nitrate reduction could occur and/or that several copies of the targeted genes were present in a single cell. Indeed, up to three copies of the narG gene can be present in the same bacterium (39). The loss of correlation between size and activity of the nitrate reducer community in plots amended with farmyard manure combined with mineral fertilizers (F2) could be attributed to the higher substrate concentration leading to changes in cellular regulation, as suggested by Röling (46). Other explanations might be that nitrate reducer populations, which are not targeted with our primers or with different specific activities, are selected in the F2 plots. This last hypothesis is supported by analysis of nitrate reducer community structure, which shows the separate clustering of samples from DM fertilized with F2. Thus, the significant correlations observed between differences in structure and activity of the nitrate reducer community were mainly due to the fact that samples from the F2-amended DM system differed the most in both cases (Fig. 5). This was also true for the correlations between differences in the structure and size of the nitrate reducer community (data not shown), which prevents us from drawing robust conclusions about the putative relationships between structure and activity or size of the nitrate reducer community. These results illustrate the importance of using a large gradient of environmental conditions to analyze the relationships between the size, structure, and activity of functional microbial communities.

In conclusion, we found that all of the characteristics of the nitrate reducer community (size, structure, and activity) were affected by the tillage system. While the use of direct seeding is more sustainable because it improves the soil nutrient status and allows farmers to cut costs and save time and fuel, we showed, along with previous studies, that it also can favor N losses. In the highlands of Madagascar, nitrate reduction activity was stimulated by combined organic and mineral fertilization but not by organic fertilization alone. However, both negative and positive effects of combined organic and mineral fertilization were observed on the size of the nitrate reducer community. The size of the nitrate reducer community was a significant predictor of the nitrate reduction rates but not in all treatments, which highlights the inherent complexities in understanding the relationships between the size, diversity, and activity of functional microbial communities along environmental gradients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Bru and the Sequencing and Genotyping Service (SSG) as well as Patricia Moulin for soil analysis. We also thank S. Nazaret for kindly providing the DNA from P. aeruginosa PAO1. We greatly appreciate comments from the anonymous reviewers.

This work was supported by the ACI-FNS ECCO program MUTEN no. 04CV086 from the French Ministry of Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 March 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aulakh, M., D. Rennie, and E. A. Paul. 1984. Gaseous nitrogen losses from soils under zero-till as compared with conventional-till management systems. J. Environ. Qual. 13:130-136. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avrahami, S., R. Conrad, and G. Braker. 2002. Effect of soil ammonium concentration on N2O release and on the community structure of ammonia oxidizers and denitrifiers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5685-5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggs, E. M., M. Stevenson, M. Pihlatie, A. Regar, H. Cook, and G. Cadish. 2003. Nitrous oxide emissions following application of residues and fertiliser under zero and conventional tillage. Plant Soil 254:361-370. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouwman, A. F. 1996. Direct emission of nitrous oxide from agricultural soils. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 46:53-70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bremer, J. 1965. Inorganic forms of nitrogen. In C. Black, D. Evans, J. White, L. Endminger, and F. Clarks (ed.), Methods in soil analysis. Part 2. American Society of Agronomy, Inc., and Soil Science Society of America, Madison, WI.

- 6.Brettar, I., J. Sanchez-Perez, and M. Tréolières. 2002. Nitrate elimination by denitrification in hardwood forest soils of the Upper Rhine floodplain—correlation with redox potential and organic matter. Hydrobiologia 469:11-21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broder, M. W., J. W. Doran, G. A. Petersen, and C. R. Fenster. 1984. Fallow tillage influence on spring populations of soil nitrifiers, denitrifiers, and available nitrogen. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 48:1060-1067. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bru, D., A. Sarr, and L. Philippot. 2007. Relative abundances of proteobacterial membrane-bound and periplasmic nitrate reductases in selected environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5971-5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruns, M. A., J. R. Stephen, G. Kowalchuk, J. I. Prosser, and E. A. Paul. 1999. Comparative diversity of ammonia oxidizer 16S rRNA gene sequences in native, tilled, and successional soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2994-3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calderon, F. J., L. E. Jackson, K. M. Scow, and D. E. Rolston. 2001. Short-term dynamics of nitrogen, microbial activity, and phospholipid fatty acids after tillage. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 65:118-126. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter-Boggs, L., P. D. Stahl, M. J. Lindstrom, and T. E. Schumacher. 2003. Soil microbial properties under permanent grass, conventional tillage, and no-till management in South Dakota. Soil Till. Res. 71:15-23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter, M. R. 1986. Microbial biomass as an index for tillage-induced changes in soil biological properties. Soil Till. Res. 7:29-40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conrad, R. 1996. Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O and NO). Microbiol. Rev. 60:609-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook, R. J. 2006. Towards cropping systems that enhance productivity and sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:18389-18394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cookson, R., D. V. Murphy, and M. M. Roper. 2008. Characterizing the relationships between soil organic matter components and microbial function and composition along a tillage disturbance gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40:763-777. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalal, R. C., P. A. Henderson, and J. M. Glasby. 1991. Organic-matter and microbial biomass in a vertisol after 20-year of zero-tillage. Soil Biol. Biochem. 23:435-441. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dambreville, C., S. Hallet, C. Nguyen, T. Morvan, J. C. Germon, and L. Philippot. 2006. Structure and activity of the denitrifying community in a maize-cropped field fertilized with composted pig manure or ammonium nitrate. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 56:119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deiglmayr, K., L. Philippot, U. A. Hartwig, and E. Kandeler. 2004. Structure and activity of the nitrate-reducing community in the rhizosphere of Lolium perenne and Trifolium repens under long-term elevated atmospheric pCO2. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49:445-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doran, J. W. 1987. Microbial biomass and mineralizable nitrogen distributions in no-tillage and plowed soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 5:68-75. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doran, J. W. 1980. Microbial changes associated with residue management with reduced tillage. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 44:518-524. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doran, J. W. 1980. Soil microbial and biochemical changes associated with reduced tillage. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 44:765-771. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doran, J. W., E. T. Elliott, and K. Paustian. 1998. Soil microbial activity, nitrogen cycling, and long-term changes in organic carbon pools as related to fallow tillage management. Soil Till. Res. 49:3-18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enwall, K., L. Philippot, and S. Hallin. 2005. Activity and composition of the denitrifying bacterial community respond differently to long-term fertilization. Appl. Environ. Microb. 71:8335-8343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan, M. X., A. F. MacKenzie, M. Abbott, and F. Cadrin. 1997. Denitrification estimates in monoculture and rotation corn as influenced by tillage and nitrogen fertilizer. Can. J. Soil Sci. 77:389-396. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng, Y., A. C. Motta, D. W. Reeves, C. H. Burmester, E. v. Santen, and J. A. Osborne. 2003. Soil microbial communities under conventional-till and no-till continuous cotton systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35:1693-1703. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Granastein, D. M., D. F. Bezdicek, V. L. Cochran, L. F. Elliott, and J. Hammel. 1987. Long-term tillage and rotation effects on soil microbial biomass, carbon and nitrogen. Biol. Fertil. Soils 5:265-270. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grandy, A. S., and G. P. Robertson. 2007. Land-use intensity effects on soil organic carbon accumulation rates and mechanisms. Ecosystems 10:58-73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henry, S., S. Texier, S. Hallet, D. Bru, C. Dambreville, D. Chèneby, F. Bizouard, J. C. Germon, and L. Philippot. 2008. Disentangling the rhizosphere effect on nitrate reducers and denitrifiers: insight into the role of root exudates. Environ. Microbiol. 10:3082-3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ibekwe, A. M., A. C. Kennedy, P. S. Frohne, S. K. Papiernik, C.-H. Yang, and D. E. Crowley. 2002. Microbial diversity along a transcet of agronomic zones. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 39:183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson, L. E., F. J. Calderon, K. L. Steenwerth, K. M. Scow, and D. E. Rolston. 2003. Responses of soil microbial processes and community structure to tillage events and implications for soil quality. Geoderma 114:305-317. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kandeler, E. 1996. Nitrate reductase activity, p. 176-179. In F. Schinner, R. Öhlinger, E. Kandeler, and R. Margesin (ed.), Methods in soil biology. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 32.Kandeler, E., and K. E. Böhm. 1996. Temporal dynamics of microbial biomass, xylanase activity, N-mineralisation and potential nitrification in different tillage systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 4:181-191. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandeler, E., D. Tscherko, and H. Spiegel. 1999. Long-term monitoring of a microbial biomass, N mineralisation and enzyme activities of a Chernozem under different tillage management. Biol. Fertil. Soils 28:345-351. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kowalchuk, G. A., and J. R. Stephen. 2001. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: a model for molecular microbial ecology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:485-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mantel, N. 1967. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 27:209-220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mogge, B., E.-A. Kaiser, and J.-C. Munch. 1999. Nitrous oxide emissions and denitrification N-losses from agricultural soils in the Bornhöved Lake region: influence of organic fertilizers and land-use. Soil Biol. Biochem. 31:1245-1255. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palma, R. M., M. Rimolo, M. Saubidet, and M. Conti. 1997. Influence of tillage system on denitrification in maize-cropped soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 25:142-146. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul, J. W., E. G. Beauchamp, and X. Zhang. 1993. Nitrous and nitric-oxide emissions during nitrification and denitrification from manure-amended soil in the laboratory. Can. J. Soil Sci. 73:539-553. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philippot, L. 1999. Dissimilatory nitrate reductases in bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1446:1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Philippot, L. 2005. Tracking nitrate reducers and denitrifiers in the environment. Biochim. Soc. Trans. 33:204-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philippot, L. 2006. Use of functional genes to quantify denitrifiers in the environment. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philippot, L., J. Čuhel, N. P. A. Saby, D. Chèneby, A. Chroňáková, D. Bru, D. Arrouays, F. Martin-Laurent, and M. Šimek. 2 March 2009. Mapping field-scale spatial patterns of size and activity of the denitrifier community. Environ. Microbiol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Philippot, L., and S. Hallin. 2005. Finding the missing link between diversity and activity using denitrifying bacteria as a model functional community. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:234-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Philippot, L., S. Hallin, and M. Schloter. 2007. Ecology of denitrifying prokaryotes in agricultural soil. Adv. Agron. 96:135-190. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Philippot, L., S. Piutti, F. Martin-Laurent, S. Hallet, and J. C. Germon. 2002. Molecular analysis of the nitrate-reducing community from unplanted and maize-planted soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6121-6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Rabenarivo, M., J. Andriamiaramiantraferana, R. Michellon, N. Moussa, A. Brauman, J. Louri-Toucet, and L. Chapuis-Lardy. Emissions in-situ de N2O d'un ferralsol argileux Malgache cultivé en système sous semis direct ou labour traditionnel. Etude Gestion Sols, in press.

- 46.Röling, W. F. M. 2007. Do microbial numbers count? Quantifying the regulation of biogeochemical fluxes by population size and cellular activity. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62:202-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roussel-Delif, L., S. Tarnawski, J. Hamelin, L. Philippot, M. Aragno, and N. Fromin. 2005. Frequency and diversity of nitrate reductase genes among nitrate-dissimilating Pseudomonas in the rhizosphere of perennial grasses grown in field conditions. Microb. Ecol. 49:63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salles, J. F., J. D. van Elsas, and J. A. van Veen. 2006. Effect of agricultural management regime on Burkholderia community structure in soil. Microb. Ecol. 52:267-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staley, T., W. W. Caskey, and D. G. Boyer. 1990. Soil denitrification and nitrification potentials during the growing season relative to tillage. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 54:1602-1608. [Google Scholar]

- 50.West, T. O., and W. M. Post. 2002. Soil organic carbon sequestration rates by tillage and crop rotation: a global data analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 66:1930-1946. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolsing, M., and A. Prieme. 2004. Observation of high seasonal variation in community structure of denitrifying bacteria in arable soil receiving artificial fertilizer and cattle manure by determining T-RFLP of nir gene fragments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 48:261-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright, A. L., F. M. Hons, and J. E. Matocha. 2005. Tillage impacts on microbial biomass and soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics of corn and cotton rotations. Appl. Soil Ecol. 29:85-92. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.