Abstract

We describe a previously healthy patient with chronic otitis media complicated with cerebellar abscess caused by Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens. The organism was identified based on conventional biochemical identification methods, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the hsp65 gene, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The patient was treated successfully with debridements and prolonged antibiotic therapy.

CASE REPORT

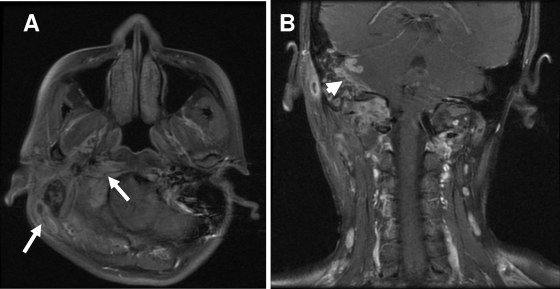

A 36-year-old female farmer who denied any history of systemic medical illness had persistent purulent discharge from the right auditory channel for more than 2 months. Chronic otitis media was diagnosed, and the patient initially received tympanoplasty and oral amoxicillin. However, poor wound healing and fever developed later, accompanied by right facial pain, dizziness, and limited range of motion on the right side of the neck for 4 weeks. The patient then visited a local hospital and received intravenous flomoxef (an oxacephalosporin) and reconstructive surgery of the auditory meatus (meatoplasty) with drainage of pus. Gram stain of material from the abscess showed no organisms, but pus culture later yielded a putative rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterium. However, the patient's symptoms persisted, and the patient was referred to National Taiwan University Hospital. On admission, blood pressure was 102/58 mm Hg, heart rate was 88 beats per minute and regular, respiratory rate was 22 breaths per minute, and temperature was 38°C. Right-side neck swelling and tenderness were noted. Neurological examination disclosed mild cerebellar ataxia. Leukocyte count was 8.96 × 103/μl with 82.4% neutrophils. Hemoglobin was 11.0 g/dl. Antinuclear antibody; complements (C3 and C4); blood lymphocytes of CD4 and CD8 surface markers; and serum immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgG, and IgM were all within normal limits. Blood anti-human immunodeficiency virus test was negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck revealed complicated right otitis media, otitis interna, and mastoiditis with osteomyelitis of the skull base and first cervical spine with intracranial spread of leptomeningeal thickening at the right posterior fossa (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

MRIs of the head and neck show multiple abscess formation involving the perivertebral space of the right upper neck and right skull base (mastoid bone, right occipital condyle, and C1 lateral mass) (arrows) (A) and an intracranial abscess of the right cerebellum (arrowhead) (B) caused by Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens.

Vigorous surgical debridements with mastoidectomy and drainage of pus were performed three times after admission. The patient received 6 weeks of intravenous imipenem (500 mg every 6 h) and amikacin (750 mg daily), followed by oral ciprofloxacin (500 mg every 12 h), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg every 12 h), and clarithromycin (500 mg every 12 h). A follow-up brain MRI 2 months after the initiation of therapy revealed substantial improvement of lesions. During follow-up at the outpatient clinic, the patient's condition was improved and the patient remained healthy and afebrile with a normal white blood cell count.

Microbiology.

The isolate was a gram-positive and partially acid-fast bacillus. The isolate grew well at 37°C but not at 42°C on a blood agar plate. The biochemical profile of the isolate produced by an API Coryne identification system (Biomérieux, Las Halles, France) disclosed Rhodococcus species. The isolate could hydrolyze tyrosine but could not hydrolyze xanthine in a nocardia ID quad agar plate (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD).

A previously described PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism identification scheme that used an amplified 440-bp segment of the 65-kDa heat shock protein gene (hsp65) was performed by using the two primers TB11 (5′-ACCAACGATGGTGTGTCCAT-3′) and TB12 (5′-CTTGTCGAACCGCATACCCT-3′) (9). The unique fragments of our isolate digested by HinfI (440 bp) and MspI (313/135 bp) were compatible with the identification of Tsukamurella species.

Further identification of the isolate was performed by 16S rRNA gene (1,490 bp) sequencing using a pair of universal primers, 8FLP (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492RPL (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (10). The sequences obtained (1,080 bp) were compared with published sequences in the GenBank database by using the BLASTN algorithm (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast). The closest match observed was obtained with Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens strain M12400 (GenBank accession no. AY254699.1) (maximal score, 1,818; E value, 0.0; and maximal identity, 99% [1,078/1,080]). The following nine strains also had an E value of 0.0 and maximal identity of 99%: Tsukamurella inchonensis strain ATCC70082 (GenBank accession no. AF283281.1; maximal score, 1,818), T. inchonensis strain ATCC25938 (GenBank accession no. AF283282.1; maximal score, 1,818), T. inchonensis strain IMMIB D-771T (GenBank accession no. X85955.1; maximal score, 1,818), Tsukamurella spumae strain N1173 (GenBank accession no. AF238512.1; maximal score, 1,807), Tsukamurella paurometabola (GenBank accession no. AF283280.1; maximal score, 1,796), Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens strain DSM44234 (GenBank accession no. AF238514.1; maximal score, 1,784), T. tyrosinosolvens strain M95570 (GenBank accession no. AF263916.1; maximal score, 1,784), T. tyrosinosolvens isolate D-1397 (GenBank accession no. Y12246.1; maximal score, 1,784), and T. tyrosinosolvens isolate D-1498 (GenBank accession no. Y12245.1; maximal score, 1,784). The identification of the isolate was in accordance with T. tyrosinosolvens and not other Tsukamurella species due to the ability to decompose tyrosine and no growth at 42°C (1, 11). The second set of primers, PSL2 (forward; 5′-AGGATTAGATACCCTGGTAGTCCA-3′) and P13P3 (reverse; 5′-AGGCCCGGGAACGTATTCAC-3′), were also used as described previously (8). The resulting sequence (559 bp) gave a 100% identification for Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens (GenBank accession no. AY254699.1).

Discussion.

Tsukamurella species are obligate aerobic, gram-positive, partially acid-fast, nonmotile bacilli that belong to the order Actinomycetales (6). Tsukamurella bacteria share many features with other Actinomycetales, such as Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Gordonia, and rapidly growing Mycobacterium bacteria, and might be misidentified as belonging to one of these genera when standard biochemical tests are used (1). Infections caused by Tsukamurella species are rare (1, 2, 4-8, 11). Most reported cases of Tsukamurella infection were related to intravascular catheters or prosthetic devices and associated with an immunocompromised condition (malignancy, postchemotherapy, chronic renal failure, and AIDS) (1, 2, 4-8, 11). Brain abscess caused by Tsukamurella has not been reported. We report for the first time a previously healthy patient who had chronic otitis media complicated with cerebellar abscess caused by T. tyrosinosolvens.

The clinical syndromes in reported cases of Tsukamurella infection include bacteremia (1), lung infection (2), conjunctivitis (3), infection of a knee prosthesis and a defibrillator (4, 5), cutaneous infection (6), and peritonitis (7). Most of the Tsukamurella infections reported were related to intravascular catheterizations, implantation of prosthetic devices, or immunocompromised conditions (such as malignancy, postchemotherapy, chronic renal failure and AIDS) (1, 2, 4-8, 11). Our patient might have acquired this pathogen which colonized in the ear from soil during work in the field, with otitis media developing subsequent to ear injury.

Accurate identification of Tsukamurella by phenotypic methods is difficult. The microbiological characteristics of Tsukamurella, including morphology on culture medium, slow growth, and weak acid-alcohol-fastness, may lead to the diagnosis of Corynebacterium, Rhodococcus, Nocardia, Gordonia, or Mycobacterium species. A PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of hsp65 has been reported to be useful for the identification of all clinically significant species and taxa of aerobic actinomycetes (9). For identifying unusual pathogens, 16S rRNA sequencing is a relatively rapid and reliable new molecular technique (8). However, 16S rRNA gene sequences have been found to be not discriminative enough for the identification of certain species, including Tsukamurella species, because of small differences in the 16S rRNA gene sequence in various Tsukamurella species. The groEL gene has been reported to be useful for speciation of a variety of bacteria (11). However, in the GenBank database, groEL gene sequences were available for only two Tsukamurella species: T. tyrosinosolvens (GenBank accession no. U90204) and T. paurometabola (GenBank accession no. AF352578). Further studies of groEL gene sequencing of multiple strains of each species of Tsukamurella should be performed to verify its suitability for Tsukamurella speciation. The ability to decompose tyrosine and negative growth at 42°C of our isolate suggested that the isolate was not T. paurometabola or T. inchonensis (1, 11).

The optimal management of infections caused by Tsukamurella bacteria remains to be determined. Although there is no recommended standard susceptibility method for Tsukamurella species, most case reports showed that Tsukamurella isolates were susceptible to amikacin, clarithromycin, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole but resistant to penicillin, cefoxitin, and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (1, 6, 11). Based on the treatment principles for nocardiosis and atypical mycobacterial infections, combinations of several antimicrobial agents have been proposed for the treatment of Tsukamurella infections. The combination of a beta-lactam (including carbapenem) and an aminoglycoside or rifamycins, along with removal of medical devices, appears to be the treatment of choice (6). In our patient with intracranial invasion of the cerebellum, we selected an initial combination of intravenous imipenem and amikacin, followed by oral clarithromycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.

The length of treatment for infections caused by Tsukamurella bacteria has not been determined and should be individualized according to clinical response. As in Rhodococcus or Nocardia infections, especially in immunocompromised hosts, frequent relapses can be expected and prolonged oral suppressive treatment is recommended. Since our patient had no evidence of immunosuppression, it seemed appropriate to maintain the treatment until symptom relief and improvement in the image studies were documented.

In conclusion, we report for the first time a patient who had chronic otitis media complicated with cerebellar abscess caused by T. tyrosinosolvens. Newer molecular biological techniques can provide accurate identification of Tsukamurella bacteria and contribute to the appropriate selection of definitive therapy for infection due to this organism.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 March 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcaide, M. L., L. Espinoza, and L. Abbo. 2004. Cavitary pneumonia secondary to Tsukamurella in an AIDS patient. First case and a review of the literature. J. Infect. 4917-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almehmi, A., A. K. Pfister, R. McCowan, and S. Matulis. 2004. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection caused by Tsukamurella. W. V. Med. J. 100185-186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elshibly, S., J. Doherty, J. Xu, R. B. McClurg, P. J. Rooney, B. C. Millar, H. Shah, T. C. Morris, H. D. Alexander, and J. E. Moore. 2005. Central line-related bacteraemia due to Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens in a haematology patient. Ulster Med. J. 7443-46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granel, F., A. Lozniewski, A. Barbaud, C. Lion, M. Dailloux, M. Weber, and J. L. Schmutz. 1996. Cutaneous infection caused by Tsukamurella paurometabolum. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23839-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larkin, J. A., L. Lit, J. Sinnott, T. Wills, and A. Szentivanyi. 1999. Infection of a knee prosthesis with Tsukamurella species. South. Med. J. 92831-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz, M. A., S. R. Tabet, A. C. Collier, C. K. Wallis, L. C. Carlson, T. T. Nguyen, M. M. Kattar, and M. B. Coyle. 2002. Central venous catheter-related bacteremia due to Tsukamurella species in the immunocompromised host: a case series and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35e72-e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaer, A. J., and C. A. Gadegbeku. 2001. Tsukamurella peritonitis associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Clin. Nephrol. 56241-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheridan, E. A., S. Warwick, A. Chan, M. Dall'Antonia, M. Koliou, and A. Sefton. 2003. Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens intravascular catheter infection identified using 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36e69-e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steingrube, V. A., R. W. Wilson, B. A. Brown, K. C. Jost, Jr., Z. Blacklock, J. L. Gibson, and R. J. Wallace, Jr. 1997. Rapid identification of clinically significant species and taxa of aerobic actinomycetes, including Actinomadura, Gordona, Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces, and Tsukamurella isolates, by DNA amplification and restriction endonuclease analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35817-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turenne, C. Y., L. Tschetter, J. Wolfe, and A. Kabani. 2001. Necessity of quality-controlled 16S rRNA gene sequence databases: identifying nontuberculous Mycobacterium species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 393637-3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woo, P. C., A. H. Ngan, S. K. Lau, and K. Y. Yuen. 2003. Tsukamurella conjunctivitis: a novel clinical syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413368-3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]