Abstract

Pyochelin (Pch) is one of the two major siderophores produced and secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 to assimilate iron. It chelates iron in the extracellular medium and transports it into the cell via a specific outer membrane transporter, FptA. We used the fluorescent properties of Pch to show that this siderophore chelates, in addition to Fe3+ albeit with substantially lower affinities, Ag+, Al3+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cr2+, Cu2+, Eu3+, Ga3+, Hg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Sn2+, Tb3+, Tl+, and Zn2+. Surprisingly, the Pch complexes with all these metals bound to FptA with affinities in the range of 10 nM to 4.8 μM (the affinity of Pch-Fe is 10 nM) and were able to inhibit, with various efficiencies, Pch-55Fe uptake in vivo. We used inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry to follow metal uptake by P. aeruginosa. Energy-dependent metal uptake, in the presence of Pch, was efficient only for Fe3+. Co2+, Ga3+, and Ni2+ were also transported, but the uptake rates were 23- to 35-fold lower than that for Fe3+. No uptake was seen for all the other metals. Thus, cell surface FptA has broad metal specificity at the binding stage but is much more selective for the metal uptake process. This uptake pathway does not appear to efficiently assimilate any metal other than Fe3+.

Iron is essential for the growth and development of living systems; it functions as a catalyst in some of the most fundamental enzymatic processes, including oxygen metabolism, electron transfer, and DNA and RNA synthesis. However, in aerobic environments, iron is found as highly insoluble ferric hydroxide complexes, and these forms severely limit the bioavailability of iron. The maximum concentration of free Fe3+ in solution at a pH close to 7 has been estimated to be about 10−18 M (40). To acquire iron, most microorganisms produce efficient, low-molecular-weight chelating agents, called siderophores, that can deliver iron into cells via active transport systems (5, 44). Siderophores have an extremely high affinity for ferric iron (Ka = 1043 and 1032 M−1 for enterobactin and pyoverdine [Pvd], respectively [2, 32]), but they also form complexes with metals other than Fe3+, although with a lower affinity. For example, the formation constants for the complexes of the hydroxamate siderophore desferrioxamine B with Ga3+, Al3+, and In3+ are between 1020 and 1028 M−1, and that with Fe3+ is 1030 M−1 (19); the constants for Pvd with Zn2+, Cu2+, and Mn2+ are between 1017 and 1022 M−1, and that with Fe3+ is 1032 M−1 (8). Siderophores also bind strongly to actinides, including thorium, uranium, neptunium, and plutonium (18, 28, 33, 34, 39).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative bacterium commonly found in soil and water; it is also an opportunistic pathogen frequently encountered in hospitals, causing morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised and cystic fibrosis patients. The strain P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692 (PAO1) synthesizes two major siderophores, Pvd and pyochelin (Pch) (20). Pch, the focus of this paper, is a poorly water-soluble, low-molecular-weight thiazoline derivative [2(2-o-hydroxy-phenyl-2-thiazolin-4-yl)-3-methylthiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid] (14), which binds Fe3+ with a stoichiometry of 2:1 (Pch to Fe3+) (42) and a stability constant of 2 × 105 M−1 (determined in ethanol) (13). This stability constant is low for a siderophore and may be higher in aqueous media. Pch biosynthesis is modulated by both the amount of iron present in the environment and the amount of iron already acquired by the bacteria. In the presence of iron, the repression occurs via the cytoplasmic Fur protein, which binds to the promoters of pchR (23, 29), an AraC-like regulatory protein (25). In the absence of iron, the PchR proteins positively regulate the biosynthesis of Pch (25). The structure of the Pch outer membrane receptor from P. aeruginosa PAO1, FptA, loaded with Pch-Fe, has been determined (11). The structure of FptA is typical of this class of transporter (http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/Membrane_Proteins_xtal.html): a transmembrane 22-β-stranded barrel occluded by an N-terminal domain containing a mixed four-stranded β-sheet. The Pch binding pocket is composed principally of hydrophobic and aromatic residues (Phe114, Leu116, Leu117, Met271, Tyr334, Gln395, and Trp702), consistent with the siderophore's hydrophobicity. One Pch molecule complexed with iron was found in the binding site, thus providing the first three-dimensional structure of this siderophore. In this structure, Pch provides a tetradentate coordination of iron, and ethylene glycol, which is not specifically recognized by the protein, provides a bidentate coordination (11). Another 1:1:1 complex between Pch (tetradentate), cepabactin (Cep) (a bidentate siderophore), and iron(III) has been isolated from Burkholderia cepacia culture media and characterized (22); it binds FptA via the Pch molecule, with an affinity intermediate between those for Pch2-Fe and Cep3-Fe (siderophore-to-Fe3+ stoichiometries of 2:1 and 3:1, respectively). Pch has three chiral centers at positions C4′, C2″, and C4″. Removal of the C4′ chiral center did not affect the binding properties or the iron uptake ability. However, after removal of both the C4′ and C2″ chiral centers, the molecule still bound to FptA but was unable to transport iron (26).

The relatively low affinity of Pch for Fe3+ and the possible availability of ligation sites other than oxygen (i.e., sulfur and nitrogen) have led to the notion that the Pch/FptA system may be able to transport metals other than iron into the bacteria. Indeed, Pch chelates vanadium, and the complex formed becomes toxic for P. aeruginosa (4). It also chelates Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Mo6+, and Ni2+ ions (27, 43), but no data are available about whether these Pch-metal complexes are recognized and transported by FptA. We therefore investigated the behavior of the Pch/FptA uptake pathway of P. aeruginosa PAO1 in the presence of 16 different metals. We found that Pch is able to chelate all the metals tested (Ag+, Al3+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cr2+, Cu2+, Eu3+, Fe3+, Ga3+, Hg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Sn2+, Tb3+, Tl+, and Zn2+). All of these Pch-metal complexes except Pch-Hg were able to bind to FptA with affinities in the range of 10 nM to 4.8 μM (the affinity of Pch-Fe is 10 nM) and were able to inhibit, with various efficiencies, Pch-55Fe uptake in vivo. In the presence of Pch, substantial proton motive-dependent uptake was observed only for Fe3+, although Ga3+, Co2+, and Ni2+ were also taken up at clearly lower rates. Our findings suggest that the FptA binding site may interact with Pch in complex with diverse metals, but the high specificity of the uptake mechanism in P. aeruginosa allows efficient accumulation only of Fe3+.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Pch was prepared as described previously (45). Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) was purchased from Sigma. The metals studied were in the following forms: AgNO3 (Sigma), AlCl3 (Sigma), CdCl2 · 2.5H2O (Probalo), CoCl2 · 6H2O (Strem), CrCl2 (Strem), CuCl2 · 2H2O (Strem), EuCl3 (Aldrich), FeCl3 (Prolabo), Ga(NO3)2 · 24H2O (Strem), HgCl2 (Sigma), MnSO4 (Prolabo), NiCl2 · 4H2O (Strem), Pb(NO3)2 (Aldrich), SnCl2 (Prolabo), TbCl3,6H2O (Strem), Tl2SO4 (Fluka), and ZnCl2 (Alfa Aesar). All the metal salts were prepared at a concentration of 50 mM in 0.5 N HCl or 0.5 N HNO3 to ensure solubilization.

Bacterial strains and growth media.

Wild-type P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (35) and the following four mutants were used (Table 1): PAD07, a strain deficient in Pch and Pvd synthesis (41); PAO6297, a strain deficient only in Pch synthesis (38); PAO6428, an FptA-deficient mutant (24); and CDC5(pPVR2), a strain overproducing FpvA and deficient in Pvd synthesis (3, 37). All the strains were grown overnight in a succinate medium (16) in the presence of 50 μg/ml tetracycline and 100 μg/ml streptomycin for strain PAD07 and 150 μg/ml carbenicillin for strain CDC5(pPVR2).

TABLE 1.

P. aeruginosa strains used in this study

Fluorescence analyses of Pch-metal complexes.

Fluorescence experiments were performed with a PTI (Photon Technology International TimeMaster, Bioritech) spectrofluorometer. For all experiments, the samples were excited at 347 nm. To follow metal complexation by Pch, 25 μM Pch was incubated overnight at room temperature in the presence of 12.5 μM of metal in 1 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) buffer.

55Fe uptake by P. aeruginosa.

55Fe uptake assays in the presence of Pch and various metals were carried out as reported for the FptA/Pch system (26). The solutions of metal ions (1 μM and 10 μM) were first preincubated at 5 mM in the presence of 20 equivalents of Pch in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) to allow Pch-metal complexes to form. PAD07 cells were prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1 and incubated at 37°C in the presence or absence of the various preincubated Pch-metal complexes. The transport assays were then started by adding 100 nM Pch-55Fe to the cells. Pch-55Fe was prepared as described previously with a 10-fold isotopic dilution of iron and a 20-fold excess of Pch relative to 55Fe (26). Transport assay mixtures were incubated for 45 min and then filtered, and the retained radioactivity was counted. For controls, the experiment was repeated by leaving out successively the metals; the metals and Pch (used to define 100% of 55Fe transport [see Fig. 3]); and the metals, Pch, and cells.

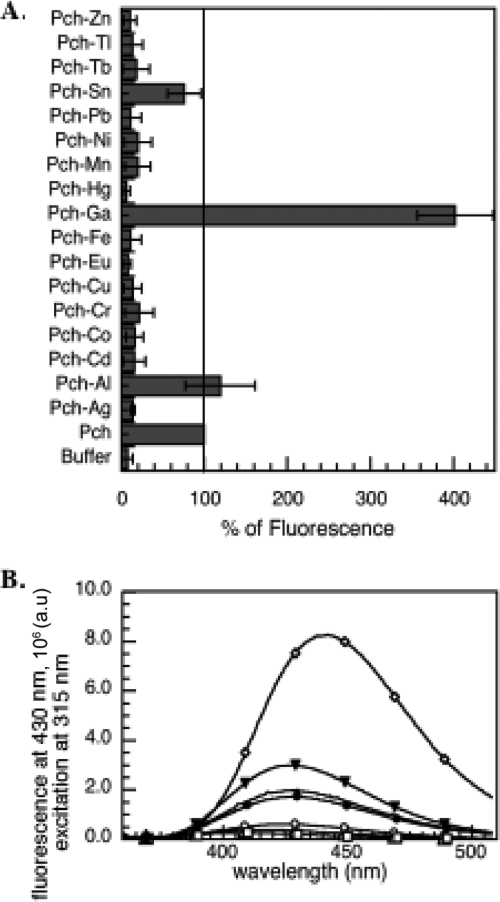

FIG. 3.

Competition by unlabeled Pch-metal for the binding of Pch-55Fe to FptA in vivo. Experiments were carried out as described in Materials and Methods with 1 nM Pch-55Fe, Pch- and Pvd-deficient PAD07 cells at an OD600 of 0.6, incubation at 0°C, and various concentrations of metal-free Pch or of Pch-metal at Pch/metal ratios of 1:2, 2:1, and 1:10. The values reported are representative of two experiments, which gave similar results. These data were used to calculate the Ki values presented in Table 2.

Incorporation of metals.

An overnight culture of CDC5(pPVR2), in iron-limited medium, was centrifuged. The supernatant containing Pch produced by CDC5(pPVR2) was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membrane and the final Pch concentration determined by OD310 (ɛ = 4,200 M−1 liter−1 cm−1). The Pch concentration was adjusted to 250 μM, and this Pch solution was incubated overnight in the presence of 12.5 μM of each metal in a final volume of 8 ml of succinate medium (solutions A).

An overnight culture of PAD07 or K2388, growth in iron-limited medium, was prepared at an OD600 of 1 in succinate medium. Half of the bacterial suspension was incubated for 15 min at 4°C in the presence of 200 μM CCCP (20 mM in ethanol). Pch-metal complexes (solutions A) were added to the bacterial cells to give a final concentration of metal of 5 μM, with or without CCCP, in a final volume of 10 ml. The tubes were then incubated for 45 min at 37°C and 200 rpm and centrifuged. The supernatants were collected, filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane, and acidified to pH 1.0 with 20% HNO3. Bacterial pellets were washed once with ultrapure water and dried at 50°C for 48 h in glass tubes (prewashed with 20% HNO3). Cells were mineralized by treatment with 68% (vol/vol) HNO3 for 24 h at room temperature. The volume was brought to 10 ml with ultrapure water, and samples were filtered on a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane if necessary and analyzed with an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) apparatus (Jobin-Yvon, Ultima) at the following wavelengths (in nm): 328.068 for Ag+, 396.152 for Al3+, 214.438 for Cd2+, 238.892 for Co2+, 206.149 for Cr2+, 324.754 for Cu2+, 259.94 for Fe3+, 294.364 for Ga3+, 194.163 for Hg2+, 257.61 for Mn2+, 231.604 for Ni2+, 220.353 for Pb2+, 189,989 for Sn2+, and 213.856 for Zn2+. The concentrations of the metals were determined in succinate medium: 0.00 μM for Ag+, 1.957 μM for Al3+, 0.006 μM for Cd2+, 0.008 μM for Co2+, 0.049 μM for Cr2+, 0.258 μM Cu2+, 0.292 μM for Fe3+, 0.022 μM for Ga3+, 0.056 μM for Mn2+, 0.002 μM for Ni2+, 0.023 μM for Pb2+, 0.076 μM for Sn2+, and 0.084 μM for Zn2+.

Ligand binding assays using 55Fe.

For ligand binding assays using 55Fe, Pch-metal complexes were prepared by incubating 10 mM Pch overnight in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) in the presence of metals at 1 mM, 5 mM, or 50 mM. The volumes were then adjusted with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0. The in vivo binding affinity constants (Ki) of Pch-metal complexes to FptA were determining as follows. PAD07 cells were washed twice with an equal volume of fresh medium and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer at an OD600 of 0.6. The cells were then incubated for 1 h at 0°C to avoid iron uptake (10) in a final volume of 500 μl with 1 nM of Pch-55Fe (prepared as described above) and various concentrations of unlabeled metal-loaded Pch (0 to 100 μM). The mixtures were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 3 min, and the supernatants containing the unbound siderophore (labeled or not labeled) were removed. The radioactivity in the tubes containing the cell pellet was counted in scintillation cocktail. The Ki of the siderophores were calculated from the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s), which were determined in competition experiments according to the equation of Cheng and Prusoff (9): Ki = IC50/(1 + L/Kd), where L is the concentration of radiolabeled ligand and Kd is its equilibrium dissociation constant determined experimentally. The Kd of Pch-Fe for FptA is 0.54 ± 0.19 nM, as determined previously (21).

As a control, the amount of trace metal was determined by ICP-AES in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and the results were as follows: 0.017 μM for Ag+, 0.182 μM for Al3+, 0.000 μM for Cd2+, 0.024 μM for Co2+, 0.028 μM for Cr2+, 0.126 μM for Cu2+, 0.104 μM for Fe3+, 0.068 μM for Ga3+, 0.012 μM for Mn2+, 0.116 μM for Ni2+, 0.018 μM for Pb2+ and 0.038 μM for Zn2+; and for the stock solution of metal-free Pch at 100 μM: 0.007 μM for Ag+, 1.526 μM for Al3+, 0.045 μM for Cd2+, 0.106 μM for Co2+, 0.136 μM for Cr2+, 0.155 μM for Cu2+, 0.140 μM for Fe3+, 0.370 μM for Ga3+, 0.114 μM for Mn2+, 0.003 μM for Ni2+, 0.074 μM for Pb2+, and 0.407 μM for Zn2+.

RESULTS

Ability of Pch to interact with metals other than Fe3+.

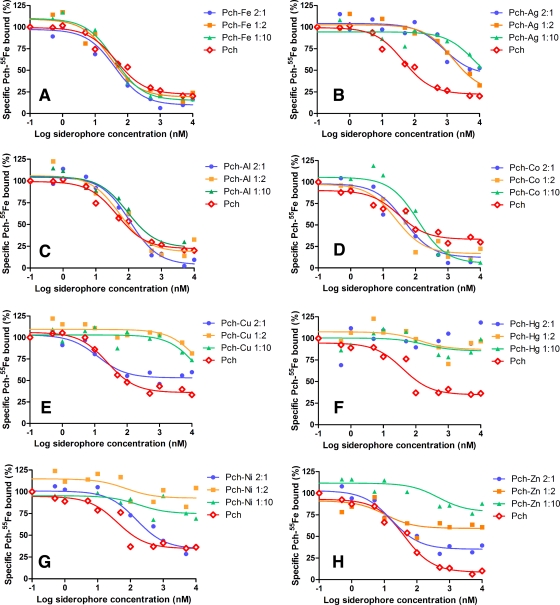

Pch is a fluorescent siderophore with a maximum fluorescence emission at 430 nm in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) buffer (excitation at 347 nm). When loaded with Fe3+, this fluorescence is completely quenched (21). The presence of metals causes spectral variations of siderophores or synthetic chelators, and these variations are used to determine the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of ligand-metal interactions (7, 17, 30, 31). We used these properties to investigate whether Pch is able to chelate other metals more or less efficiently than it does Fe3+. Pch at neutral pH chelates Fe3+ with a 2:1 stoichiometry (Pch to Fe) (12, 42), so a twofold excess of Pch relative to the metal was used. Some metals interact with siderophores with slow kinetics; therefore, Pch was incubated overnight in the presence of each metal. None of the fluorescent spectral changes observed (Fig. 1A and B) were detected in control experiments in which each metal was incubated in the buffer in the absence of siderophore. The fluorescent spectral changes were seen only in the presence of both metal ion and siderophore, indicating that they were due to the formation of a complex between Pch and the metal tested. There was a 1.2-fold increase of fluorescence in the presence of Al3+ and a 4.0-fold increase in the presence of Ga3+ (Fig. 1B), with a shift in the maximum emission of fluorescence for Pch-Ga (maximum at 442 nm). In the presence of Sn2+, Pch fluorescence was quenched by 20%. For all the other metals (Ag+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cr2+, Cu2+, Eu3+, Hg2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Tb3+, Tl+, and Zn2+), between 75 and 95% of the fluorescence was quenched (Fig. 1A). The residual fluorescence probably corresponds to residual free Pch. In conclusion, Pch was apparently able to chelate all the metal ions tested.

FIG. 1.

(A) Variation of Pch fluorescence in the presence of various metal ions. The fluorescence at 430 nm (excitation wavelength, 347 nm) of metal-free Pch was taken as the reference (100%). Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Fluorescence spectra of Pch incubated in the presence of Ag+ (▵), Al3+ (▾) Ga3+ (⋄), Fe3+ (○), Hg3+ (▪), and Sn2+ (•). The fluorescence spectrum of metal-free Pch is shown as a black line. For both panels, 25 μM Pch was incubated overnight with 12.5 μM metals in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and the fluorescence was then monitored (excitation wavelength, 347 nm). a.u., arbitrary units.

Ability of the Pch-metal complexes to inhibit Pch-55Fe uptake.

Pch-Fe is transported across the P. aeruginosa outer membrane by the transporter FptA. This is the only route by which this ferric-siderophore complex can enter these bacteria (FptA mutants are unable to transport Pch-Fe [26]). To determine if FptA at the cell surface can bind Pch in complex with metals other than Fe3+, we tested the ability of Pch-metal complexes to inhibit Pch-55Fe uptake. This indicates whether the binding site of FptA binds the Pch-metal but does not reveal whether there is Pch-metal uptake by the transporter. As a reference, Pvd- and Pch-deficient cells (PAD07) were incubated in the presence of 100 nM Pch-55Fe for 45 min to evaluate the amount of 55Fe transported in the absence of any competition (Fig. 2). During this period, the cell concentration was stable; no growth of P. aeruginosa occurred when 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer was used. The experiment was repeated using 200- and a 2,000-fold excesses of metal-free Pch relative to Pch-55Fe, and no 55Fe uptake inhibition was observed. Finally, the experiment was repeated in the presence of each Pch-metal complex in 10- and 100-fold excesses relative to the concentration of Pch-55Fe. For each metal, the complex was prepared by incubating the metal overnight in the presence of a 20-fold excess of Pch.

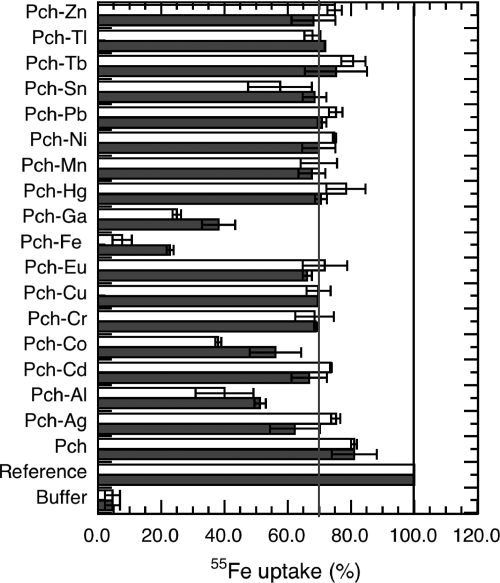

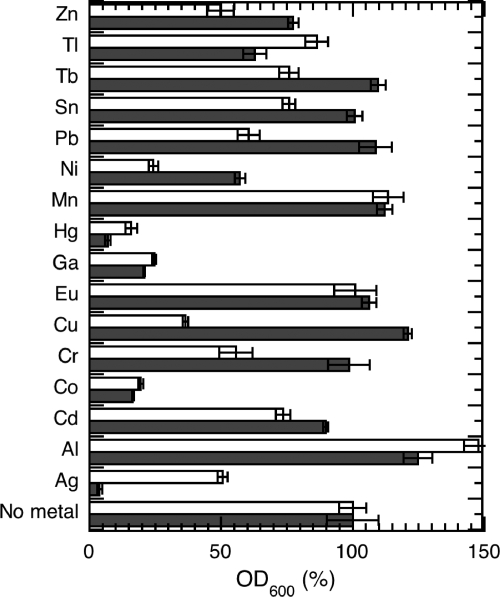

FIG. 2.

Ability of Pch-metal complexes to inhibit Pch-55Fe uptake. Pvd- and Pch-deficient PAD07 cells at an OD600 of 1 were incubated for 45 min in the presence of 100 nM Pch-55Fe at 37°C. The mixtures were then filtered and radioactivity counted. The amount of 55Fe transported in this experiment was used as a reference (defined as 100% uptake). This experiment was repeated in the absence of cells (bars labeled “Buffer”). The experiment was also repeated in the presence of cells and an excess of metal-free Pch and in the presence of cells and of each Pch-metal complex (black and white bars correspond to 1 and 10 μM metal, respectively). Pch-metal complexes were prepared by preincubating each metal in the presence of a 20-fold excess of Pch overnight. As a control, for each metal tested, the experiment was repeated in the absence of cells (data not shown). All the data are means and standard deviations from three independent experiments. The black line indicates the 100% of Pch-55Fe uptake, and the gray line shows that most of the Pch-metal complexes inhibited 28% of the Pch-55Fe uptake.

All metals in complex with Pch inhibited Pch-55Fe uptake (Fig. 2). The inhibition rates for Pch-Ga (62% and 75% for, respectively, 10 and 100 equivalents of Pch-Ga) were the closest to those observed for nonradioactive Pch-Fe (78% and 94% for 10 and 100 equivalents of Pch-Fe, respectively). Pch-Al and Pch-Co had inhibition rates of between 44% and 62%. For all the other metals tested, the inhibition rate was around 30%. We checked that these observed Pch-55Fe uptake inhibitions were not due to cell death resulting from metal toxicity; the viable cell counts were evaluated by plating on agar after incubation (45 min) in the presence of Pch-Fe and Pch-metal complexes. None of the 16 metals tested was toxic under the experimental conditions used here (data not shown); the uptake inhibition values observed (Fig. 2) were clearly not due to cell death. In conclusion, Pch-55Fe uptake was strongly inhibited by Pch-Al, Pch-Co, and Pch-Ga and was inhibited, albeit less strongly, by Pch in complex with all the other metals. Pch-Al, Pch-Co, and Pch-Ga must have affinities for FptA in the same range as that of Pch-Fe, and all the other Pch-metal complexes must have significantly lower affinities.

Affinities of Pch-metal complexes for FptA.

FptA seems to be able to bind Pch-Al, Pch-Co, and Pch-Ga and probably also Pch in complex with all the other ion metals tested (Fig. 2). We used competition experiments to evaluate the affinities of the Pch-metal complexes for FptA (Fig. 3, Table 2). As described previously, when Pvd- and Pch-deficient PAD07 cells were incubated in the presence of Pch-55Fe, a radioactive signal corresponding to the specific binding of Pch-55Fe to FptA was observed (21, 26). This signal was absent in a strain lacking FptA, such as PAO6428 (Table 1). In the present work, Pvd- and Pch-deficient cells (PAD07) were incubated at 0°C, to avoid uptake, in the presence of 1 nM Pch-55Fe and a series of concentrations of metal-free Pch or Pch-metal prepared at ratios (Pch to metal) of 2:1, 1:2, and 1:10. After incubation, the cells were pelleted and the radioactivity counted. We are aware that this experiment has limitations since it involves four equilibriums: (i) formation of Pch-55Fe, (ii) formation of the Pch-metal complexes, and (iii and iv) formation of either FptA-Pch-55Fe or FptA-Pch-metal complexes at the cell surface. Therefore, the goal here was not to determine accurate affinity constants of the Pch-metal complexes for FptA but to compare the stabilities of the different FptA-Pch-metal complexes with the stability of FptA-Pch-Fe. Both Pch-55Fe and the Pch-metal complexes were prepared by preincubating the siderophore with the metals before addition to the bacteria. To check if the Pch-55Fe concentration stayed constant even in the presence of high ion metal concentrations, the competition experiment was carried out first in the presence of PAD07 cells, 1 nM Pch-55Fe, and increasing concentrations of siderophore-free ion metals. Cell-bound radioactivity did not decrease with concentration of siderophore-free ion metals lower than 10 μM (data not shown), indicating that all the metals at the concentrations used in the experiment described in Fig. 3 and Table 2 did not compete so as to dissociate Pch-55Fe. The Pch-55Fe concentration stayed stable under our experimental conditions. The formation of Pch-metal complexes was followed using the fluorescent properties of Pch. As shown in Fig. 1A, when a Pch/metal ratio of 2:1 was used, most but not all of the Pch was in complex with an ion metal. When the 1:2 and 1:10 ratios were used, all Pch was saturated with metals (data not shown). By working with an increasing concentration of metals in relation to siderophore, we assist the formation of Pch-metal, and we should have with the ratio of 2:1 a mixture of Pch and Pch-metal and with the ratio of 1:10 mostly Pch-metal and no more metal-free Pch. However, we know nothing about the stoichiometry of the Pch-metal complexes formed; when the concentration of siderophore was higher in relation to metals, the ion metals were probably chelated by more than one Pch, and when the metal/siderophore ratio was reversed, ion metals were probably chelated with just one siderophore as described previously for Fe3+ (42).

TABLE 2.

Inhibition constantsa

| Metal |

Ki (nM)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-free Pch

|

Pch-metal complex with a Pch/metal ratio of:

|

|||||||

| 2:1

|

1:2

|

1:10

|

||||||

| Mean | 95% Confidence interval | Mean | 95% Confidence interval | Mean | 95% Confidence interval | Mean | 95% Confidence interval | |

| Ag+ | 15.0 | 8.6-26.1 | 266.1 | 64.5-1,097.0 | 495.0 | 186.3-1,315.0 | 2,198.3 | 48.6-9.9 × 104 |

| Al3+ | 15.0 | 8.6-26.1 | 36.1 | 20.8-62.7 | 17.7 | 6.4-48.7 | 30.9 | 12.6-76.2 |

| Cd2+ | 10.2 | 3.3-3.17 | 6.9 | 1.8-26.2 | 27.3 | 5.4-137.5 | 26.3 | 7.7-89.4 |

| Co2+ | 10.2 | 3.3-3.17 | 14.6 | 4.7-45.6 | 8.2 | 3.0-22.0 | 39.3 | 16.0-96.7 |

| Cr2+ | 8.2 | 4.8-14.0 | 8.0 | 1.1-59.3 | 31.0 | 13.6-70.7 | 117.3 | 21.4-641.7 |

| Cu2+ | 8.2 | 4.8-14.0 | 4.1 | 1.3-13.1 | 4,568.7 | 5.2-4.0 × 106 | 4,834.3 | 7.2-3.3 × 106 |

| Eu3+ | 13.4 | 4.3-41.5 | 16.3 | 6.2-43.0 | 35.1 | 6.5-190.6 | 42.6 | 6.3-286.6 |

| Fe3+ | 15.0 | 8.6-26.1 | 13.6 | 6.9-26.9 | 10.0 | 4.5-22.5 | 13.0 | 7.6-22.4 |

| Ga3+ | 13.4 | 4.3-41.5 | 32.4 | 16.4-63.9 | 33.2 | 11.9-92.3 | 11.6 | 2.9-47.3 |

| Hg2+ | 13.4 | 4.3-41.5 | NBb | NB | NB | |||

| Mn2+ | 13.4 | 4.3-41.5 | 51.1 | 9.9-264.3 | 12.9 | 6.8-24.7 | 42.2 | 14.5-123.0 |

| Ni2+ | 13.4 | 4.3-41.5 | 51.4 | 19.3-136.5 | NB | NB | ||

| Pb2+ | 13.6 | 7.9-23.3 | 5.4 | 2.1-13.9 | 12.4 | 1.6-94.6 | 11.6 | 4.1-15.8 |

| Sn2+ | 13.6 | 7.9-23.3 | 8.5 | 4.6-15.8 | 35.7 | 7.6-167.3 | 29.6 | 8.1-108.1 |

| Tb3+ | 13.6 | 7.9-23.3 | 16.0 | 4.9-52.9 | 27.4 | 12.2-61.5 | 73.5 | 11.6-464.7 |

| Tl+ | 13.6 | 7.9-23.3 | 8.8 | 5.1-15.0 | 28.5 | 8.4-97.4 | 31.9 | 13.4-76.0 |

| Zn2+ | 13.6 | 7.9-23.3 | 5.6 | 2.7-11.6 | NB | NB | ||

Ki values were determined from competition experiments against Pch-55Fe. PAD07 cells at an OD600 of 0.6 were incubated with 1 nM Pch-55Fe and various concentrations of metal-free Pch, of siderophore-free metal ions, or of Pch-metal complexes at Pch/metal ratios: 1:2, 2:1, and 1:10. The experiments were carried out at 0°C to avoid iron uptake. The values are representative of two experiments, which gave similar results.

NB, no binding.

When Pvd- and Pch-deficient PAD07 cells were incubated in the presence of Pch-55Fe and increasing concentrations of metal-free Pch, cell-bound radioactivity decreased, indicating competition between Pch and Pch-55Fe for binding to FptA at the cell surface (Fig. 3). The Ki of metal-free Pch was 12.8 ± 2 nM. ICP-AES measurements indicated that the Pch was metal free (see Materials and Methods). ICP-AES is a suitable spectrometric technique to determine trace amounts of elements. It is based on measurement of light emission from excited atoms and ions, in argon plasma, and each element has a specific emission wavelength that can be used to determine its concentration. Concerning the metal loading status of Pch, we cannot exclude the possibility that this Pch preparation may have been contaminated by trace elements from the buffer or the cell suspension, and were this case, the Pch would not be 100% metal free. However, the same buffer and cells were used for all the metals tested, so the concentration of any such trace elements would be the same for all the Ki values determined in Table 2. This displacement of Pch-55Fe by metal-free Pch on FptA was used as a reference for all the Pch-metal complexes tested in this experiment.

Cell-bound radioactivity also decreased with increasing concentrations of Pch-metal (Fig. 3), except for Hg2+ (Pch/metal ratios of 2:1, 1:2, and 1:10) (Fig. 3F and Table 2), Ni2+ (1:2 and 1:10) (Fig. 3G and Table 2), and Zn2+ (1:2 and 1:10) (Fig. 3H and Table 2). FptA is not able to bind Pch-Hg and has difficulty binding to Pch-Ni and Pch-Zn. The Ki of Pch preincubated with Fe3+ was, as for metal-free Pch, in the range of 10 to 13.6 nM depending on the Pch/metal ratio tested (Fig. 3A and Table 2). Surprisingly, Pch-Pb had a Ki for FptA that was similar to that of Pch-Fe. Pch in complex with Al3+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cr2+, Eu3+, Ga3+, Mn2+, Sn2+, Tb3+, and Tl+ had Ki in the range of 6.9 nM (Pch/metal ratio of 2:1) to 117.3 nM (Pch/metal ratio of 1:10). According to Fig. 1A, under our experimental conditions, there was formation of Pch-metal complexes with all these metals. Therefore, the displacements observed were not due to the presence of metal-free Pch competing with Pch-55Fe for FptA but were due to a competition between Pch-metal complexes and Pch-55Fe for the transporter. We may conclude that Pch-Al, Pch-Cd, Pch-Co, Pch-Cr, Pch-Eu, Pch-Ga, Pch-Mn, Pch-Pb, Pch-Sn, Pch-Tb, and Pch-Tl complexes are apparently able to bind to FptA with affinities close to that of metal-free Pch and Pch-Fe. For Pch-Ag and Pch-Cu, the displacement curves were shifted to higher concentrations of Pch-metal (Fig. 3B and E; Table 2), and this was so for all three Pch/metal ratios used. Ki in the ranges of 266.1 to 2,198.3 nM and 4.1 to 4,834.3 nM were determined for Pch-Ag and Pch-Cu, respectively. These decreases of the affinities when the concentrations of ion metals increase in relation to siderophore may reflect a difference in the affinities of FptA for Pch-metal in different stoichiometric forms. As mentioned above, when the concentration of siderophore was higher in relation to metals, the ion metals were probably chelated by more than one Pch, and when the metal/siderophore ratio was reversed, ion metals perhaps were chelated with just one siderophore as described previously for Fe3+ (42). In the cases of Ag+ and Cu2+, but also in the cases of Ni2+ and Zn2+, we may have a good recognition of the metal when chelated by two Pchs, a bad recognition for Ag+ and Cu2+, and no recognition for Ni2+ and Zn2+, when the metal was chelated by just one siderophore. Indeed, 2:1 and 1:1 Pch-metal complexes will be different in size and in the conformation of the siderophore, and therefore recognition by the FptA transporter must be affected. The data presented here do not allow us to answer this question. Further studies of the Pch chelation properties will be necessary.

In conclusion, the displacement experiments summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 3 showed that FptA is able to bind Pch in complex with all the metals tested except Hg2+ and perhaps Ni2+ and Zn2+. The Ki determined were very close to the one found for Pch-Fe, except for Ag+ and Cu2+, where an important decrease was observed.

Metal transported into P. aeruginosa cells in the presence of Pch.

Thus, Pch can chelate metals other than Fe3+, and these siderophore-metal complexes can bind to FptA at the cell surface. It has been suggested that Pch may transport metals other than Fe3+ into P. aeruginosa cells (15, 43). We therefore investigated which of the ion metals that Pch can chelate are transported by the Pch/FptA uptake pathway. To avoid confusion due to metal uptake by the Pvd pathway, the Pch- and Pvd-deficient strain PAD07 was used for this experiment. This experiment required large amounts of Pch, so not all the metals were tested. Bacteria were incubated in the presence of each Pch-metal complex tested. After incubation, the cells were harvested and the amount of metal inside the bacteria and/or bound at the cell surface was determined by ICP-AES. To discriminate between metal transported in a energy-dependent manner and metal diffusing through porins, the experiment was repeated in the presence of the protonophore CCCP. CCCP inhibits the proton motive force of the inner membrane and therefore abolishes energy-dependent uptake by bacteria (1, 10, 36). In the presence of CCCP, FptA is still able to bind Pch-Fe but is unable to transport it into the periplasm of P. aeruginosa (10, 36).

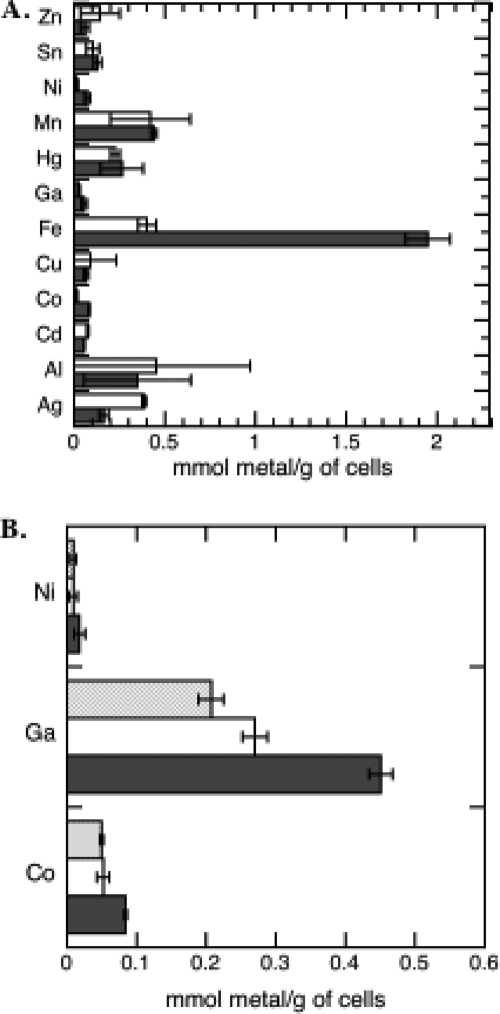

The uptake observed in the presence of CCCP (Fig. 4A) corresponds to diffusion of the siderophore-free metals across the outer membrane via porins or bound at the cell surfaces. The uptake observed in the absence of CCCP corresponds to the sum of diffusion of free metals through porins, metal bound at the cell surfaces, and energy-dependent uptake of siderophore-metal complexes. A difference between values in the presence and absence of CCCP was observed only for Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Ga3+. Therefore, only these metals, when chelated by Pch, could be transported by a proton motive force-dependent process. However, the uptakes of Co2+, Ni2+, and Ga3+ were very much lower than that of Fe3+: 23-fold lower for Ni2+, 26-fold lower for Co2+, and 35-fold lower for Ga3+. The 0.43 μmol of Fe3+/g of cells found in the presence of CCCP probably corresponds to iron already present inside the cells before the beginning of the experiment (imported during the previous growth of the cells). To investigate the involvement of FptA in this energy-dependent uptake of Ni2+, Co2+, and Ga3+, the experiment was repeated in parallel with PAD07 and an FptA mutant, K2388 (Fig. 4B). The same differences between the values in the presence and absence of CCCP for PAD07 and between those for K2388 and PAD07 in the absence of CCCP were observed, confirming that these three metals were transported by the Pch/FptA pathway.

FIG. 4.

Proton motive force-dependent metal incorporated into P. aeruginosa cells by the Pch uptake pathway. (A) Pvd- and Pch-deficient PAD07 cells at an OD600 of 1 were incubated at 37°C with 5 μM of each Pch-metal complex in the presence (white bars) or absence (black bars) of 200 μM CCCP. After 45 min of incubation, the cells were harvested and washed and the metal content determined by ICP-AES. Pch-metal complexes were prepared by incubating each metal in the presence of a 20-fold excess of Pch overnight. The data are means and standard deviations from three independent experiments. (B) The experiment was repeated in parallel with PAD07 cells in the presence (white bars) or absence (black bars) of CCCP and with K2388 cells (ΔfptA and Pvd−) (grey bars) for Co2+, Ga3+, and Ni2+.

Concerning Pch-Ni, the competition experiments (Fig. 3G) showed a Ki of 51 nM when the complex was prepared, like in the uptake assay (Fig. 4), by mixing 2 equivalents of Pch with 1 equivalent of Ni2+ and no binding when 2 or 10 equivalents of Ni2+ were incubated with 1 of Pch. These data may appear to be in contradiction with the observed energy-dependent uptake of Ni2+. The only explanation is that when two Pchs chelate Ni2+, the complex is able to bind to FptA and to be transported. However, Ni2+ in complex only with one Pch is unable to be recognized by FptA.

Toxicity of the metals for P. aeruginosa and role of the Pch pathway in the toxicity.

We tested for any correlation between the toxicity of a metal and its apparent ability to be transported into P. aeruginosa by the Pch pathway. CDC5(pPVR2) (a strain unable to produce Pvd) and PAD07 (a strain unable to produce both Pvd and Pch) were grown in the presence of 100 μM of each metal (Fig. 5) in an iron-free medium. Since the formation of the Pch-metal complexes is an important step in the process of uptake of a metal by the Pch pathway, we incubated the cells just in the presence of the metals and not in the presence of the preformed Pch-metal complexes. Hg2+, Ag+, Co2+, Cr2+, and Ga3+ were the most toxic for CDC5(pPVR2), and Ni2+ and Cr2+ inhibited growth but to a lesser extent. For the metals that can be transported by the Pch uptake pathway (Ni2+, Ga3+, and Co2+ in Fig. 4), the observed toxicity was not modulated by the presence or the absence of Pch. The toxicity of these metals must be due to diffusion of siderophore-free metals through porins. Surprisingly, CDC5(pPVR2), the strain able to produce Pch, was more sensitive to Ag+, Al3+, Tl+, and Hg2+ than PAD07. This indicates that these four metals may be toxic because of an incorporation into the bacteria by the Pch pathway. Since no uptake of these metals was detected by ICP-AES (Fig. 4), the uptake rates must be low and could not be measured by our approach. Clearly further investigation is necessary to confirm this hypothesis. Finally, strain PAD07 was apparently more sensitive than CDC5(pPVR2) to Cd2+, Cr2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Sn2+, and Tb3+. The absence of Pch in the extracellular medium thus appeared to increase the sensitivity to these metal ions. This may be an indirect consequence; Pch chelating the metal in the extracellular medium may decrease its diffusion through the porins.

FIG. 5.

Role of the Pch pathway in P. aeruginosa metal toxicity. P. aeruginosa CDC5(pPVR2) (a strain unable to produce Pvd) (black bars) and PAD07 (a strain unable to produce both Pvd and Pch) (white bars) were grown overnight in the presence or absence of each metal ion (100 μM). After 20 h of culture, the OD600 was determined. The culture in the absence of metal was used as the reference (100%). The data are means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Pch has an affinity for Fe3+ of 2 × 105 M−1 (determined in ethanol) (14) and ligation sites other than oxygen, and these features led to suggestions that it may be able to transport ions of metals other than iron into P. aeruginosa. The ability of Pch to chelate Cu2+, Co2+, Mo6+, and Ni2+ in addition to Fe3+ was also shown previously (43) and strengthened this idea. We confirmed that Pch can chelate these four metals, and in addition, we show that it also chelates Ag+, Al3+, Cd2+, Cr2+, Eu3+, Ga3+, Hg2+, Mn2+, Pb2+, Sn2+, Tb3+, Tl+, and Zn2+ (Fig. 1). However, the conformations, sizes, and stabilities of the resulting Pch-metal complexes must be diverse and depend on the atomic weight and the coordination of the 16 metals tested. Similar work with Pvd has shown that this chromopeptide siderophore is also able to chelate all the metals tested (6).

FptA at the cell surface binds Pch in a complex with any of the ion metals we tested except Hg2+. Most of the metals (Al3+, Cd2+, Co2+, Cr2+, Eu3+, Ga3+, Mn2+, Pb+, Sn2+, Tb3+, and Tl+) have an affinity very close to the one determined for Pch-Fe and metal-free Pch (Table 2). Only Ag+ and Cu2+ had lower affinities. In the cases of Ni2+ and Zn2+, a binding with a Ki equivalent to that of Pch-Fe was observed only when the complexes were prepared by mixing two equivalents of Pch with one of metal. No correlation was observed between all the Ki determined (Table 2) and the abilities of the different Pch-metal complexes to inhibit the Pch-55Fe uptake (Fig. 2). Pch-Ga, Pch-Al, Pch-Co, and Pch-Cr were the most efficient in inhibiting Pch-55Fe uptake. All the others had uptake inhibition values of around 25 or 30%. This lack of metal specificity of the FptA binding site was surprising because outer membrane siderophore transporters are characterized by very high siderophore selectivity. Concerning the siderophore selectivity of FptA, we have shown previously that Pch chelates Fe3+ with a stoichiometry of 2:1 (Pch to Fe3+) and that it also complexes with iron in conjunction with another bidentate ligand such as cepabactin or ethylene glycol (26, 42). Determination of the structure of FptA loaded with Pch-Fe and docking experiments showed that it is only the Pch molecule part of these complexes that binds to the transporter (11, 26). The second dentate can be a molecule completely different from Pch and not have a large effect on the interaction with FptA. Moreover, in vivo binding assays and docking experiments using the X-ray structure of FptA showed that the binding properties and the iron uptake abilities were affected by removal of the C4″ and C2″ chiral centers of Pch; the molecule still bound to FptA but was unable to transport iron (26). The overall binding mode of this iron-complexed analogue was inverted, demonstrating how siderophore selective FptA is. The high siderophore specificity of FptA does not appear to be consistent with the low metal specificity. The explanation perhaps is in the structure of FptA-Pch-Fe (12). Indeed, none of the residues of the siderophore binding sites interact with the metal. The transporter interacts only with the Pch, which forms a sort of shell around the metal. Apparently only the exterior of this shell, and not the metal sheltered within, is important for binding with the outer membrane transporter.

ICP-AES experiments (Fig. 4) showed that only Fe3+ is transported efficiently by the Pch/FptA system; Co2+, Ga3+, and Ni2+ were also transported, but with much lower efficiencies (26-fold, 35-fold, and 23-fold lower, respectively). Two of the ion metals transported by this pathway are those which, in complex with Pch, were able to efficiently inhibit Pch-55Fe uptake. However, the sensitivity of ICP-AES is limited, and we cannot exclude the possibility that other ion metals able to bind to FptA at the cell surface when chelated by the siderophore were also imported by an energy-dependent process but with uptake rates too low to be detected. Previously, Visca et al. have shown that Co2+ at 10 μM, like Fe3+ and Mo(VI), Ni2+, and Cu2+ at 100 μM, repressed Pch synthesis and reduced expression of FptA (43). These observations are consistent with the uptake of Pch-Ni and Pch-Co that we observed (Fig. 4) and suggest that Mo(VI) and Cu2+ are transported as well into the bacteria by the Pch pathway. A regulation of the biosynthesis of Pch and expression of FptA by the metals involves the fact that they are able to enter the cytoplasm and interact with PchR.

These various findings show that the metal specificity of the binding step at the level of FptA is broader than the metal specificity of the uptake process for the Pch/FptA pathway. Similar data were obtained with the Pvd uptake pathway in P. aeruginosa: there was a large metal specificity for the binding stage for FpvA, but only Cu2+, Ga3+, Mn2+, and Ni2+ were transported and with uptake rates between 7- and 42-fold lower than that of Fe3+ (6). This may be a common property of all siderophore outer membrane transporters. They can be “polluted” at the cell surface by binding of their siderophore in complex with metals other than Fe3+ because the recognition involves the siderophore itself and not the chelated metal. Nevertheless, an unknown mechanism allows the transporter to import only siderophore loaded with Fe3+ into the periplasm. The other siderophore-metal complexes are translocated through the channel formed in the protein during the uptake process with a substantially lower efficiency or not at all. The reasons for this rigorous metal selectivity will probably remain unclear until we know the mechanisms both of channel formation in outer membrane siderophore transporters and of translocation of ferric-siderophore across these channels. During this uptake process, the nature of the metal chelated by the siderophore is clearly important; it is unknown whether this is due to its size, its coordination, or its interaction with the transporter during the translocation process.

In conclusion, our findings reported here clearly show that the FptA/Pch system is not involved in the uptake of large amounts of metals other than Fe3+. The system is highly specific for iron but is also able to transport Ga3+, a metal very similar in size and coordination to Fe3+, and three other biologically relevant metals that can be used as cofactors by enzymes of the bacteria [Co2+ and Ni2+ (43; this study) and Mo(VI) (43)]. Further investigation will be necessary to find out the fate of these Pch-metal complexes transported into the bacteria; the biologically relevant metals may be released from the siderophore and used as cofactors by enzymes, or the undesirable siderophore-metal complexes may be excreted again in the extracellular medium by efflux pumps.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly funded by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and by a grant from the ANR (Agence Nationale de Recherche, ANR-05-JCJC-0181-01).

We thank Cornelia Reimmann for strains PAO6297 and PAO6428.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 March 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, H., G. Zeder-Lutz, J. Greenwald, I. J. Schalk, H. Célia, and F. Pattus. 2006. Interaction of TonB with outer membrane receptor FpvA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1885752-5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht-Gary, A. M., S. Blanc, N. Rochel, A. Z. Ocacktan, and M. A. Abdallah. 1994. Bacterial iron transport: coordination properties of pyoverdin PaA, a peptidic siderophore of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Inorg. Chem. 336391-6402. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ankenbauer, R., L. F. Hanne, and C. D. Cox. 1986. Mapping of mutations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa defective in pyoverdin production. J. Bacteriol. 1677-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baysse, C., D. De Vos, Y. Naudet, A. Vandermonde, U. Ochsner, J. M. Meyer, H. Budzikiewicz, M. Schafer, R. Fuchs, and P. Cornelis. 2000. Vanadium interferes with siderophore-mediated iron uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 1462425-2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boukhalfa, H., and A. L. Crumbliss. 2002. Chemical aspects of siderophore mediated iron transport. Biometals 15325-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braud, A., F. Hoegy, K. Jezequel, T. Lebeau, and I. J. Schalk. New insights into the metal specificity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdine-iron uptake pathway. Environ. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Carrano, C. J., H. Drechsel, D. Kaiser, G. Jung, B. Matzanke, G. Winkelmann, N. Rochel, and A. M. Albrecht-Gary. 1996. Coordination chemistry of the carboxylate type siderophore rhizoferrin: the iron(III) complex and its metal analogs. Inorg. Chem. 356429-6436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, Y., E. Jurkewitch, E. Bar-Ness, and Y. Hadar. 1994. Stability constants of pseudobactin complexes with transition metals. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 58390-396. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng, Y. C., and W. H. Prusoff. 1973. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 223099-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clément, E., P. J. Mesini, F. Pattus, M. A. Abdallah, and I. J. Schalk. 2004. The binding mechanism of pyoverdin with the outer membrane receptor FpvA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on its iron-loaded status. Biochemistry 437954-7965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobessi, D., H. Celia, and F. Pattus. 2005. Crystal structure at high resolution of ferric-pyochelin and its membrane receptor FptA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Mol. Biol. 352893-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobessi, D., H. Celia, and F. Pattus. 2004. Crystallization and X-ray diffraction analyses of the outer membrane pyochelin receptor FptA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Acta Crystallogr. D 601919-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox, C. D., and R. Graham. 1979. Isolation of an iron-binding compound from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 137357-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox, C. D., K. L. Rinehart, Jr., M. L. Moore, and J. C. Cook, Jr. 1981. Pyochelin: novel structure of an iron-chelating growth promoter for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:4256-4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuppels, D. A., A. Stipanovic, A. Stoessi, and J. B. Sothers. 1987. The constitution and properties of a pyochelin-zinc complex. Can. J. Microbiol. 652126-2130. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demange, P., S. Wendenbaum, C. Linget, C. Mertz, M. T. Cung, A. Dell, and M. A. Abdallah. 1990. Bacterial siderophores: structure and NMR assigment of pyoverdins PaA, siderophores of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15692. Biol. Metals 3:155-170. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhungana, S., C. Ratledge, and A. L. Crumbliss. 2004. Iron chelation properties of an extracellular siderophore exochelin MS. Inorg. Chem. 436274-6283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durbin, P. W., N. Jeung, S. J. Rodgers, P. N. Turowski, F. L. Weitl, D. L. White, and K. N. Raymond. 1989. Removal of 238Pu(IV) from mice by poly-cathecholate, -hydroxamate or -hydroxypyridonate ligands. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 26351-358. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evers, A., R. Hancock, A. Martell, and R. Motekaitis. 1989. Metal ion recognition in ligands with negatively charged oxygen donor groups. Complexation of Fe(III), Ga(III), In(III), Al(III) and other highly charged metal ions. Inorg. Chem. 282189-2195. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwald, J., F. Hoegy, M. Nader, L. Journet, G. L. A. Mislin, P. L. Graumann, and I. J. Schalk. 2007. Real-time FRET visualization of ferric-pyoverdine uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a role for ferrous iron. J. Biol. Chem. 2822987-2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoegy, F., H. Celia, G. L. Mislin, M. Vincent, J. Gallay, and I. J. Schalk. 2005. Binding of iron-free siderophore, a common feature of siderophore outer membrane transporters of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 28020222-20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klumpp, C., A. Burger, G. L. Mislin, and M. A. Abdallah. 2005. From a total synthesis of cepabactin and its 3:1 ferric complex to the isolation of a 1:1:1 mixed complex between iron (III), cepabactin and pyochelin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 151721-1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leoni, L., A. Ciervo, N. Orsi, and P. Visca. 1996. Iron-regulated transcription of the pvdA gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effect of Fur and PvdS on promoter activity. J. Bacteriol. 1782299-2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michel, L., A. Bachelard, and C. Reimmann. 2007. Ferripyochelin uptake genes are involved in pyochelin-mediated signalling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 1531508-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michel, L., N. Gonzalez, S. Jagdeep, T. Nguyen-Ngoc, and C. Reimmann. 2005. PchR-box recognition by the AraC-type regulator PchR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires the siderophore pyochelin as an effector. Mol. Microbiol. 58495-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mislin, G. L. A., F. Hoegy, D. Cobessi, K. Poole, D. Rognan, and I. J. Schalk. 2006. Binding properties of pyochelin and structurally related molecules to FptA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Mol. Biol. 3571437-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namiranian, S., D. J. Richardson, D. A. Russell, and J. R. Sodeau. 1997. Excited state properties of the siderophore pyochelin and its complex with zinc ions. Photochem. Photobiol. 65777-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neu, M. P., J. H. Matonic, C. E. Ruggiero, and B. L. Scott. 2000. Structural characterization of a plutonium(IV) siderophore complex: single-crystal structure of Pu-desferrioxamine E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 39:1442-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochsner, U. A., and M. L. Vasil. 1996. Gene repression by the ferric uptake regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: cycle selection of iron-regulated genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 934409-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palanche, T., S. Blanc, C. Hennard, M. A. Abdallah, and A. M. Albrecht-Gary. 2004. Bacterial iron transport: coordination properties of azotobactin, the highly fluorescent siderophore of Azotobacter vinelandii. Inorg. Chem. 431137-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palanche, T., F. Marmolle, M. A. Abdallah, A. Shanzer, and A. M. Albrecht-Gary. 1999. Fluorescent siderophore-based chemosensors: iron(III) quantitative determinations. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 4188-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raymond, K. N., E. A. Dertz, and S. S. Kim. 2003. Enterobactin: an archetype for microbial iron transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1003584-3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raymond, K. N., G. E. Freeman, and M. J. Kappel. 1984. Actinide-specific complexing agents: their structural and solution chemistry. Inorg. Chim. Acta 94193-204. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renshaw, J. C., V. Halliday, G. D. Robson, A. P. Trinci, M. G. Wiebe, F. R. Livens, D. Collison, and R. J. Taylor. 2003. Development and application of an assay for uranyl complexation by fungal metabolites, including siderophores. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 693600-3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Royle, P. L., H. Matsumoto, and B. W. Holloway. 1981. Genetic circularity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 145145-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schalk, I. J., C. Hennard, C. Dugave, K. Poole, M. A. Abdallah, and F. Pattus. 2001. Iron-free pyoverdin binds to its outer membrane receptor FpvA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a new mechanism for membrane iron transport. Mol. Microbiol. 39351-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schalk, I. J., P. Kyslik, D. Prome, A. van Dorsselaer, K. Poole, M. A. Abdallah, and F. Pattus. 1999. Copurification of the FpvA ferric pyoverdin receptor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with its iron-free ligand: implications for siderophore-mediated iron transport. Biochemistry 389357-9365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serino, L., C. Reimmann, H. Baur, M. Beyeler, P. Visca, and D. Haas. 1995. Structural genes for salicylate biosynthesis from chorismate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Gen. Genet. 249217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, W. L., and K. N. Raymond. 1981. Specific sequestering agents for the actinides. 6. Synthetic and structural chemistry of tetrakis(N-alkylalkanehydroxamato)thorium(IV) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1033341-3349. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiro, T. G. 1977. Chemistry and biochemistry of iron. Grune and Stratton, New York, NY.

- 41.Takase, H., H. Nitanai, K. Hoshino, and T. Otani. 2000. Impact of siderophore production on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in immunosuppressed mice. Infect. Immun. 681834-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tseng, C. F., A. Burger, G. L. A. Mislin, I. J. Schalk, S. S.-F. Yu, S. I. Chan, and M. A. Abdallah. 2006. Bacterial siderophores: the solution stoichiometry and coordination of the Fe(III) complexes of pyochelin and related compounds. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 11419-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visca, P., G. Colotti, L. Serino, D. Verzili, N. Orsi, and E. Chiancone. 1992. Metal regulation of siderophore synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and functional effects of siderophore-metal complexes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 582886-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winkelmann, G. 2002. Microbial siderophore-mediated transport. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30691-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zamri, A., and M. A. Abdallah. 2000. An improved stereocontrolled synthesis of pyochelin, a siderophore of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Tetrahedron 56249-256. [Google Scholar]