Abstract

Objective

We aimed to analyze clinical and radiological outcomes retrospectively in patients with basilar apex aneurysms treated by coiling or clipping.

Methods

Outcomes of basilar bifurcation aneurysms were assessed retrospectively in 77 consecutive patients (61 women, 16 men), ranging in age from 25 to 79 years (mean, 53.7 years) from 1999 to 2007.

Results

Forty-nine patients out of 77 patients (63.6%) presented with subarachnoid hemorrhages of the 49 patients treated with coiling, 27 (55.1%) showed complete occlusion of the aneurysm sac. Of these, 13 patients (26.5%) developed coil compaction on angiographic or MRI follow-up, with recoiling required in 9 patients (18.4%). Procedural complications of coiling were acute infarction in nine patients and the bleeding of the aneurysms in six patients. The remaining 28 patients underwent microsurgery: twenty-six of these (92.9%) with microsurgery followed up with conventional angiography. Complete occlusion of the aneurysm sac was achieved in 19 patients (73.1%). Operation-related complications of microsurgery were thalamoperforating artery injuries in three patients, retraction venous injury in two, postoperative epidural hemorrhage (EDH) in one, and transient partial or complete occulomotor palsy in 14 patients. Glasgow Outcome Scores (GOS) were 4 or 5 in 21 of 28 (75%) patients treated with microsurgery at discharge, and at 6 month follow-up, 20 of 28 (70.9%) maintained the same GOS. In comparison, GOS of four or 5 was observed in 36 of 49 (73.5%) patients treated with coiling at discharge and at 6 month follow-up, 33 of 49 patients (67.3%) maintained the GOS from discharge.

Conclusion

Basilar top aneurysms were still challenging lesions based on our series. Endovascular or microsurgery endowed with its inborn risks and procedural complications for the treatment of basilar apex aneurysms individually. Microsurgery provided better outcome in some specific basilar apex aneurysms. For reaching the most favorable outcome, endovascular modality as well as microsurgery was inevitably considered for each specific basilar apex aneurysm.

Keywords: Aneurysm, Basilar artery, Endovascular, Microsurgery

INTRODUCTION

Microsurgical treatment of basilar apex aneurysms is considered to be difficult and challenging due to their deep location and intimate relationship with cardinal perforating arteries7,32). Despite advances in microsurgical techniques, neuroanesthesia, and neuroradiology, the microsurgical treatment of basilar apex aneurysms has a higher morbidity rate than that of microsurgical treatment of anterior circulation aneurysms9). The inability to perform microsurgical clipping of basilar apex aneurysms has led to the development of other treatment modalities such as endovascular therapy4,9-12,18,24,27-29,33,35). Due to its increased safety, endovascular coil occlusion has become the treatment of choice for basilar apex aneurysms4,9,11,18,24,25,27-29,33,35). However, endovascular coil occlusion is less durable than microsurgery, as shown by its higher rates of aneurysm recanalization and regrowth13).

The efficacy of treatment modality is based on both its safety and durability. Microsurgical clipping and endovascular coil occlusion, the two treatment modalities for basilar apex aneurysms, each has its own advantages and disadvantages when compared with each other. A choice should be made based on the conditions of a patient. We therefore retrospectively evaluated the radiological and clinical outcomes of clipping and coiling performed in a single institution in patients with basilar apex aneurysms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between February 1999 and August 2007, 77 consecutive patients with basilar apex aneurysms underwent microsurgery or endovascular procedure in our institute. Patients with aneurysms exclusive to the P1 segment or those arising from the basilar artery at the superior cerebellar artery (SCA) were excluded, as were patients with unruptured basilar top aneurysms concomitant with ruptured aneurysms originating from sites other than the basilar bifurcation.

Of these 77 patients, 49 (63.6%) presented with subarachnoid hemorrhages (SAH) and 28 (36.4%) with unruptured aneurysms. Of the 49 patients with SAH, 27 (55.2%) presented with Hunt and Hess Grade I or II, and 22 (44.8%) with Grade III to V. Out of these SAH patients, 26 patients (53.1%) were treated within 3 days of the ictus, 12 patients (24.5%) between days 3 and 14, and 11 patients (22.4%) were treated after 14 days. Early surgery is general rule in our institution for patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms. However, thirty-eight patients (78%) were referred from other institutions and this limited early surgery.

Preoperative maximum fundus diameters were categorized arbitrarily as small (<10 mm), large (10 to 20 mm) or giant (>20 mm). Thus, fifty-three patients (68.8%) had small aneurysms while there were 20 patients (26%) with large aneurysms and 4 patients (5.2%) with giant aneurysms. Aneurysm neck size was scored as narrow (<4 mm) or wide (≥4 mm), as determined on the angiographic projection that best displayed the neck region in relation to the parent arteries. Thirty-two patients (41.6%) had narrow neck and 45 (58.4%) had wide neck lesions. Projection orientation of the aneurysms and bifurcation height of the basilar artery were determined from lateral angiograms. Lesions were described as projecting anteriorly, neutrally, or posteriorly, relative to a line drawn from the vertebrobasilar junction to the basilar apex. Fifteen lesions (19.5%) were anterior, 55 lesions (71.4%) were neutral, and 7 lesions (9.1%) were posterior. Bifurcations were defined as high (>10 mm superior to the mid-sellar depth), low (<5 mm inferior to the posterior clinoid processor) or neutral (those in between). Based on this categorization, 47 (61%) were high, 26 (33.8%) were neutral, and 4 (5.2%) were low.

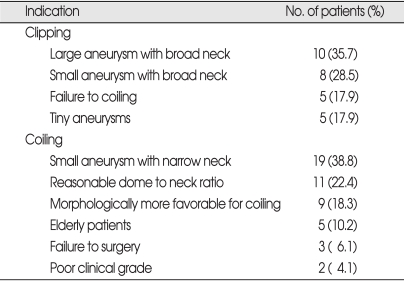

Neurosurgeons (B.D., J.A.) and neurointerventionists (D.K., C.C.) discussed about the treatment modality for each patient with basilar apex aneurysms (Table 1). Indications for clipping included the followings : 1) large aneurysms with wide necks; 2) failure of coiling; 3) small aneurysms with wide necks; and 4) tiny (<3 mm) aneurysms defined as too small for coiling. Indications for coiling included : 1) small aneurysms with narrow necks (dome to neck ratio ≥2); 2) reasonable dome to neck ratios (1< dome to neck ratio <2); 3) morphologic features more favorable for coiling; 4) elderly patient (≥65 years old); 5) failure of surgery; and 6) poor clinical grade (Hunt & Hess grade ≥4).

Table 1.

Indications of clipping or coiling for basilar apex aneurysm in our trials

Clinical outcomes were classified according to the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS). Patients who returned to work with no neurological deficits (GOS 4 or 5) were determined to have had good outcomes. Patients with any neurological deficit who were unable to work or required some level of assistance in their daily living (GOS 2 or 3) were determined to have had poor outcomes. Long-term follow-up examination consisted of outpatient chart review with the patient, caregiver, or the nearest living relative.

Postoperative angiographic results were classified as 1) complete obliteration; 2) residual neck; or 3) residual sac, according to the degree of contrast filling of the aneurysm dome. Patients with incomplete obliteration of the aneurysm underwent CT or MR head angiography to evaluate evidence of regret. Conventional angiography was performed for confirmation of recurrence or coil compaction. Postembolization angiographic results were classified as complete occlusion (class 1), residual neck (class 2), or residual aneurysm (class 3) 30, 31).

RESULTS

Clinical outcomes

Seventeen of 28 patients treated with microsurgery presented with SAH; Hunt and Hess Grade was I or II in 11 (64.8%), III in 3 (17.6%) and IV in 3 (17.6%). Six patients (35.3%) underwent surgery within 72 hours of aneurysm rupture, 4 patients (23.5%) on days 4 to 14 after ictus, and 7 patients (41.2%) after day 14. One patient became severely disabled and resulted in death after clipping due to multi-organ failure. At discharge, 13 out of 16 patients had good outcomes and three had poor outcomes. Mean follow-up time was 28.6 months. At 6 months follow-up, 12 patients among them had good and four patients had poor outcomes.

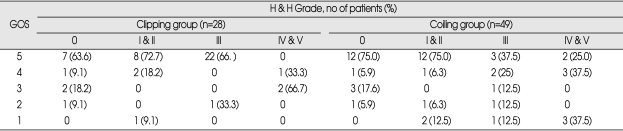

Of the 11 patients who presented with unruptured aneurysms and were treated with microsurgical clipping, 8 patients had good outcomes and 3 patients had poor outcomes, both at discharge and at 6 months follow-up (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical outcome of patients with basilar apex aneurysms treated by clipping or coiling at discharge

GOS : Glasgow outcome scale, H & H : Hunt and Hess

Of 49 patients who were treated with endovascular coiling 32 presented with SAH. Hunt and Hess Grade was I or II in 16 (50%), III in 8 (25%) and IV or V in 8 (25%). Twenty patients (62.5%) underwent endovascular coiling within 72 hours of aneurysm rupture, 8 patients (25%) on days 4 to 14 after ictus, and 4 patients (12.5%) after day 14. Six patients of this endovascular treatment group became severely disabled and resulted in death after coiling treatment. The causes of death were parent artery occlusion (n=1), bleeding of the aneurysms (n=2), multi-organ failure (n=1), acute cerebral infarction not related to the procedure (n=1), or hypovolemic shock from massive ulcer bleeding (n=1). Of the remaining 26 patients, 23 patients had a good outcome and 3 patients had a poor outcome at discharge. At 6 months follow-up, 20 patients had a good outcome, 3 patients had a poor outcome, and 3 patients were lost for follow-up evaluation.

Seventeen patients presented with unruptured aneurysms and were treated with endovascular coiling. Thirteen of 17 patients had a good outcome (Table 2). At 6 months follow-up, 14 out of 17 patients had a good outcome.

Angiographic outcomes

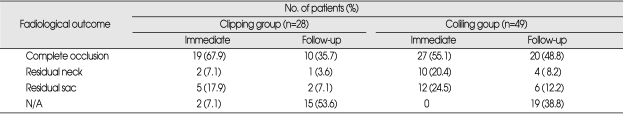

Postoperative angiography was performed in 26 (92.9%) of the 28 patients with clipped aneurysms. Two patients with no postoperative evaluation were due to poor postoperative clinical status. Postoperative angiography showed that 19 aneurysms (73.1%) had been completely obliterated. Residual neck was observed in two patients (7.7%) and residual fundus in five patients (19.2%). Four of these seven patients with residual sac or neck had follow-up CT head angiography to evaluate the residual status of aneurysms. Follow-up radiological features of residual portion in these patients were equivalent to those of immediate postoperative images (Table 3). Reasons that three patients with residual neck or sac who did not undergo follow-up evaluation were due to poor clinical outcomes (n=2) and follow-up loss (n=1).

Table 3.

Radiological outcome of patients with basilar apex aneurysms treated by clipping or coiling

N/A : not available

Complete occlusion was observed in 27 patients (55.1%), residual neck in 10 (20.4%), and residual sac in 12 (24.5%) treated with embolization. Follow-up evaluation was performed in 30 patients; with nine patients (18.3%), treated endovascularly during a second therapeutic session after significant residual or recurrent aneurysm confirmed by angiography. One patient required two additional interventions and one required three additional endovascular interventions. Of these 30 patients, 20 (66.7%) showed complete occlusion, four resulted in residual neck (13.3%), and six resulted in residual sac (20.0%) (Table 3).

Complications

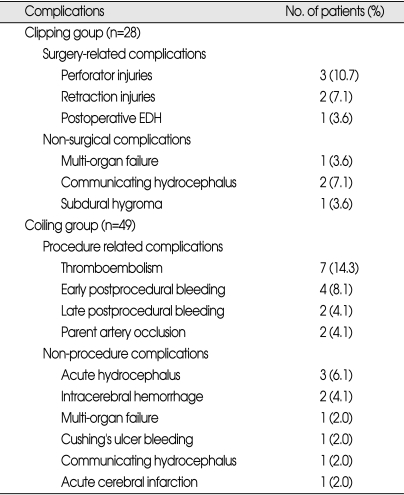

There was no surgery-related mortality in the patients with microsurgery. Six patients (21.4%) developed surgeryrelated complications without third nerve palsy : perforater injury in three patients, retraction venous injury in two patients, and postoperative epidural hemorrhage in one patient. Non-surgical complications were observed in four patients (14.3%) : communicating hydrocephalus requiring ventriculoperitoneal shunt in two patients, multi-organ failure in one patient, and subdural hygroma requiring burrhole drainage in one patient (Table 4).

Table 4.

Complications of basilar apex aneurysms treated by clipping or coiling

Procedural related complications were observed in 15 (30.6%) patients with endovascular detachable coiling : thromboembolic complications in seven patients, post procedural bleeding in six patients, and parent artery occlusion in two patients. Among the six patients with post procedural bleeding, four patients showed early post procedural bleeding within 7 days after the procedure whereas the other two patients developed late post procedural bleeding more than 5 months after embolization. Non-procedural complications were developed in nine patients; acute hydrocephalus requiring emergency external ventricular drainage in three patients, intracerebral hemorrhage related to anti-coagulation in two patients, multi-organ failure in one patient, Cushing's ulcer bleeding in one patient, communicating hydrocephalus requiring ventriculoperitoneal shunt in one patient, and acute cerebral infarction not related to embolization was in one patient (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Features of endovascular coiling

Basilar bifurcation aneurysms account for 5% to 8% of all intracranial aneurysms26). From an endovascular viewpoint, the height or direction of the tip of the basilar artery does not affect the endovascular procedure itself. In addition, the endovascular procedure does not require brain or cranial nerve retraction. Another advantage of using embolization to treat aneurysms in the basilar bifurcation artery is the relatively lower risk of compromising perforators, because these vessels usually arise from the aneurysm neck and almost never from the sac8). This anatomical characteristic enable compact coil packing of most basilar apex aneurysms. In contrast, basilar apex aneurysms sometimes incorporate into the ostia of the posterior cerebral or superior cerebellar artery, preventing complete obliteration of these aneurysms5,33). The width of the aneurysm neck and the overall size of the fundus are important features for enhancing radiological outcomes of embolization treated intracranial aneurysms. In our study, aneurysm diameter and the width of the aneurysm neck were significantly associated with radiological outcomes of basilar apex aneurysms treated by endovascular coiling.

Endovascular materials and techniques including 3D coils6), balloon remodeling techniques, double catheter techniques, and self-expandable stents1,2,16,17,19,22,23,34), can be helpful in treating wide-necked basilar apex aneurysms. These technical improvements do not increase the stability of aneurysm occlusions. However, embolizations have a critical limitation, in that endovascular access to a basilar apex aneurysm may be impossible due to significant tortousity or stenosis of the vertebral artery or basilar artery. The most significant limitations of the endovascular procedure include its lack of long-term durability, the high rate of coil compaction and the need for repeated embolizations3,10). In our series, the rates of coil compaction and repeated embolization were 24.5% and 18.3%, respectively. Rupture of previously treated aneurysms is another important guideline for assessing the durability of each treatment modality. The rate of bleeding from embolization treated aneurysms was 12.2%, with 4 patients developing aneurysm ruptures within 7 days after embolization and 2 patients showing ruptures more than 5 months after treatment. Early post procedural bleeding may be due to technical inexperience of the neurosurgeon, whereas late procedural bleeding may reflect the durability of the embolization itself. Thus, we estimate that the rate of bleeding risk arising from embolization itself was 4.1%. Long-term follow-up evaluation is required, even in patients with complete occlusion of the aneurysmal sac in basilar apex aneurysms. This relative poor outcome of basilar top aneurysms with endovascular treatment in our series might probably be due to the aneurysm morphology itself challenge to treat any modalities, the inclusion of the patients underwent with endovascular treatment during initial inexperience period, and clinically grave and elderly patients unavoidable for endovascular treatment.

Features of microsurgical clipping

Basilar apex aneurysms are among the most challenging vascular lesions, even for very experienced neurosurgeons, with endovascular techniques being the initial treatment in many centers4,9-12,18,24,27-29,33,35). A multi-center prospective trial showed that embolization was effective for treating ruptured intracranial aneurysms20,21). However, indications for surgical treatment differed somewhat from those for embolization. For example, clipping was preferred over coiling for patients with very tiny ruptured basilar apex aneurysms, those with aborted embolizations, and those with small aneurysms having broad necks. Due to differences in patient populations, even those with basilar apex aneurysms, the results of embolization cannot be directly compared with those of clipping.

We found, however, that the rates of rebleeding and repeated treatment were much lower in patients treated by clipping than in those treated with endovascular surgery. This may be due to the greater durability of microsurgery compared with embolization. A previous study reported that clipping was successful in 95% of patients with complex basilar top aneurysms, with no evidence of residual aneurysms on follow-up angiography provided14,15). Radiological complete occlusion of basilar apex aneurysms in our series was relatively worse than previous report. The main reason might be small number of patients with direct surgery and radiological result of each case might affect overall radiological outcome significantly. Although microsurgery is not always superior to embolization for basilar apex aneurysms, microsurgery may be more appropriate than endovascular treatment for some patients with ruptured tiny aneurysms or small aneurysms with broad neck.

Comparison between clipping and coiling

Indications for endovascular treatment of aneurysm have gradually extended, from an unavoidable treatment modality for patients with aneurysms contraindicated for surgery to today's primary treatment modality. Prospective multicenter trials showed that detachable coil embolization was superior to microsurgical clipping for ruptured intracranial aneurysms21,22). Since surgical treatment of basilar apex aneurysms is challenging even for highly skilled neurosurgeons, these aneurysms are usually first treated by endovascular embolization.

Detachable coil embolization, however, has limitations, including high rates of coil compaction and the need for repeated embolization3,10). The risk of bleeding after detachable coil embolization ranges from zero to 5%, which indicates its relative safe outcome. In contrast, the durability of embolization has not yet been established.

Despite the development of direct surgical methods for basilar apex aneurysms, the rate of surgical morbidity and mortality remains high. This is partly attributed to the properties of these aneurysms and anatomic factors surrounding these aneurysms. These include a narrow surgical field leading to difficult maneuverability around the aneurysm, limited tolerance of the brainstem and thalamus to proximal control, limited knowledge of the collateral blood flow system, and limited ability to dissect the perforators from the wall of the aneurysm. The chief advantage of direct surgical clipping is its durability. In our study, no patient experienced bleeding from basilar apex aneurysms after being treated with surgical clipping. Moreover, follow-up imaging of four patients with incomplete postoperative occlusion showed no recurrence of these treated aneurysms.

Due to differences in patient factors, direct surgical clipping cannot be compared with endovascular coiling for basilar apex aneurysms. Yet, each of these methods has its own advantages and limitations different from one another. Thus, the endovascular and direct surgical approaches should be regarded as equal to each other, with the most appropriate method used for each patient with a basilar apex aneurysm.

Limitations of our study

Limitations of our study were retrospective design, non-randomization of patients, and relative large number of patients with follow-up loss. Although direct comparison of the two methods was not possible, the radiological and clinical outcomes of the two methods suggested that patients who underwent microsurgical treatment were appropriately selected and produced acceptable results, whereas the durability of endovascular treatment was somewhat insufficient. In addition, we could not assess the durability of microsurgical treatment because of the considerable loss for radiological follow-up in this group. However, we did not observe any bleeding during the follow-up for aneurysms treated with clipping, and the radiological follow-up results for patients incompletely treated with clipping were not inferior to those of the previous radiological images. These results suggest that microsurgery is a durable treatment modality for basilar apex aneurysms. Reasons why relative large number of patients lost to follow-up were that radiological follow-up in patients with surgical or endovascular treatment had been not performed routinely during early period of our study and that many of patients were transferred from other remote institutes.

CONCLUSION

In spite of marked development of endovascular and microsurgical treatment basilar apex aneurysms are still considered as formidable and challenging lesions in our study. Microsurgery and endovascular treatment has its own pitfalls and benefits in the treatment of basilar apex aneurysms. Some specific basilar apex aneurysms were more appropriate for microsurgery resulting in favorable clinical and radiological outcomes. Therefore, direct microsurgery as well as endovascular treatment should be equally considered in decision making for the treatment of basilar apex aneurysm the treatment of basilar apex aneurysm. Careful decision for choosing between endovascular treatment and microsurgical clipping may improve overall outcomes in each patient with basilar apex aneurysm.

References

- 1.Akiba Y, Murayama Y, Vinuela F, Lefkowitz MA, Duckwiler GR, Gobin YP. Balloon-assisted Guglielmi detachable coiling of wide-necked aneurysms: Part I--experimental evaluation. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:519–527. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199909000-00022. discussion 527-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aletich VA, Debrun GM, Misra M, Charbel F, Ausman JI. The remodeling technique of balloon-assisted Guglielmi detachable coil placement in wide-necked aneurysms : experience at the University of Illinois at Chicago. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:388–396. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.3.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batjer HH, Samson DS. Causes of morbidity and mortality from surgery of aneurysms of the distal basilar artery. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:904–916. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bavinzski G, Killer M, Gruber A, Reinprecht A, Gross CE, Richling B. Treatment of basilar artery bifurcation aneurysms by using Guglielmi detachable coils : a 6-year experience. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:843–852. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.5.0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne JV, Guglielmi G. Endovacular Treatment of Intracranial Aneurysms. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cloft HJ, Joseph GJ, Tong FC, Goldstein JH, Dion JE. Use of three-dimensional Guglielmi detachable coils in the treatment of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1312–1314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drake CG. Bleeding aneurysms of the basilar artery. Direct surgical management in four cases. J Neurosurg. 1961;18:230–238. doi: 10.3171/jns.1961.18.2.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drake CG, Peerless SJ, Hernesniemi JA. Surgery of Vertebrobasilar Aneurysms : London, Ontario Experience on 1767 Patients. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eskridge JM, Song JK. Endovascular embolization of 150 basilar tip aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils : results of the Food and Drug Administration multicenter clinical trial. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:81–86. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.1.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman JA, Nichols DA, Meyer FB, Pichelmann MA, McIver JI, Toussaint LG, 3rd, et al. Guglielmi detachable coil treatment of ruptured saccular cerebral aneurysms: retrospective review of a 10-year single-center experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:526–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guglielmi G, Vinuela F, Duckwiler G, Dion J, Lylyk P, Berenstein A, et al. Endovascular treatment of posterior circulation aneurysms by electrothrombosis using electrically detachable coils. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:515–524. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.77.4.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Dowd CF, Barnwell SL, Fraser KW, Smith TP, et al. The efficacy of endosaccular aneurysm occlusion in alleviating neurological deficits produced by mass effect. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:659–666. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.4.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henkes H, Fischer S, Mariushi W, Weber W, Liebig T, Miloslavski E, et al. Angiographic and clinical results in 316 coil-treated basilar artery bifurcation aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:990–999. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krisht AF, Kadri PA. Surgical clipping of complex basilar apex aneurysms : a strategy for successful outcome using the pretemporal transzygomatic transcavernous approach. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:261–273. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156785.63530.4e. discussion 261-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krisht AF, Krayenbuhl N, Sercl D, Bikmaz K, Kadri PA. Results of microsurgical clipping of 50 high complexity basilar apex aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:242–250. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249265.88203.DF. discussion 250-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy DI, Ku A. Balloon-assisted coil placement in wide-necked aneurysms. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:724–727. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.4.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malek AM, Halbach VV, Phatouros CC, Lempert TE, Meyers PM, Dowd CF, et al. Balloon-assist technique for endovascular coil embolization of geometrically difficult intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:1397–1406. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200006000-00022. discussion 1406-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDougall CG, Halbach VV, Dowd CF, Higashida RT, Larsen DW, Hieshima GB. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms using electrolytically detachable coils. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:393–399. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.3.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mericle RA, Wakhloo AK, Rodriguez R, Guterman LR, Hopkins LN. Temporary balloon protection as an adjunct to endosaccular coiling of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:975–978. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199710000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, Sandercock P, Clarke M, Shrimpton J, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms : a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1267–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, Clarke M, Sneade M, Yarnold JA, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms : a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809–817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moret J, Ross IB, Weill A, Piotin M. The retrograde approach : a consideration for the endovascular treatment of aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:262–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakahara T, Kutsuna M, Yamanaka M, Sakoda K. Coil embolization of a large, wide-necked aneurysm using a double coil-delivered microcatheter technique in combination with a balloon-assisted technique. Neurol Res. 1999;21:324–326. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1999.11740939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols DA, Brown RD, Jr, Thielen KR, Meyer FB, Atkinson JL, Piepgras DG. Endovascular treatment of ruptured posterior circulation aneurysms using electrolytically detachable coils. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:374–380. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.3.0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogilvy CS, Hoh BL, Singer RJ, Putman CM. Clinical and radiographic outcome in the management of posterior circulation aneurysms by use of direct surgical or endovascular techniques. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:14–21. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200207000-00003. discussion 21-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pia HW. Classification of vertebro-basilar aneurysms. Acta Neurochir(Wien) 1979;47:3–30. doi: 10.1007/BF01404659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierot L, Boulin A, Castaings L, Rey A, Moret J. Selective occlusion of basilar artery aneurysms using controlled detachable coils : report of 35 cases. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:948–953. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199605000-00019. discussion 953-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raymond J, Roy D. Safety and efficacy of endovascular treatment of acutely ruptured aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1235–1245. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199712000-00002. discussion 1245-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raymond J, Roy D, Bojanowski M, Moumdjian R, L'Esperance G. Endovascular treatment of acutely ruptured and unruptured aneurysms of the basilar bifurcation. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:211–219. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.2.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy D, Milot G, Raymond J. Endovascular treatment of unruptured aneurysms. Stroke. 2001;32:1998–2004. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy D, Raymond J, Bouthillier A, Bojanowski MW, Moumdjian R, L'Esperance G. Endovascular treatment of ophthalmic segment aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1207–1215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schievink WI, Wijdicks EF, Piepgras DG, Chu CP, O'Fallon WM, Whisnant JP. The poor prognosis of ruptured intracranial aneurysms of the posterior circulation. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:791–795. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.5.0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tateshima S, Murayama Y, Gobin YP, Duckwiler GR, Guglielmi G, Vinuela F. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms using Guglielmi detachable coils : anatomic and clinical outcomes in 73 patients from a single institution. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1332–1339. discussion 1339-1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turk AS, Rappe AH, Villar F, Virmani R, Strother CM. Evaluation of the TriSpan neck bridge device for the treatment of wide-necked aneurysms: an experimental study in canines. Stroke. 2001;32:492–497. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallee JN, Aymard A, Vicaut E, Reis M, Merland JJ. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils : predictors of immediate and long-term results with multivariate analysis 6-year experience. Radiology. 2003;226:867–879. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2263011957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]