Abstract

Aims

To assess the impact of left ventricular (LV) volume/mass ratio on diastolic function parameters in subjects with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and healthy controls.

Methods and results

We performed echocardiography in 44 healthy controls, 35 HCM subjects, 29 DCM subjects with narrow QRS complex (DCM-n), and 27 DCM subjects with wide QRS complex (DCM-w). Mitral annulus velocity (Ea) and transmitral E-wave velocity were used to estimate time constant of isovolumic pressure decay (τ). LV flow propagation velocity (Vp) and early intraventricular pressure gradient (IVPG) were derived from colour M-mode of LV inflow. We calculated LV twist and peak untwisting rate (UntwR) by speckle tracking. Mean LV volume/mass ratio was 0.34 ± 0.09 mL/g in healthy controls, 0.15 ± 0.06 mL/g in HCM, 0.6 ± 0.2 mL/g in DCM-n, and 0.8 ± 0.3 mL/g in DCM-w patients (P < 0.001 for all groups). Resting LV ejection fractions were 63 ± 7, 64 ± 8, 31 ± 8, and 26 ± 8%, respectively (P < 0.01 vs. controls for DCM groups). In a multivariate analysis, LV volume/mass ratio remained a strong independent predictor of Vp (P < 0.001), IVPG (P = 0.009), and UntwR (P < 0.001) but not for Ea (P = 0.25).

Conclusion

LV volume/mass ratio had influences on diastolic function parameters independent of intrinsic diastolic function and filling pressures. It should be considered when assessing patients suspected of LV diastolic dysfunction.

Keywords: Left ventricular volume/mass ratio, Diastolic function, Dilated cardiomyopathy, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Ventricular torsion (twist), Echocardiography

Introduction

A wealth of data supports patient classification into specific diastolic dysfunction groups based on various parameters of left ventricular (LV) filling.1–5 This classification correlates with objective measures of cardiovascular performance such as pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) or the time constant of isovolumic pressure decay6–10 and is also a predictor of patient's symptoms and survival. The classification bases on the transmitral and pulmonary vein flow profiles and on isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT). However, the past decade introduced new markers of diastolic function that are based either on intraventricular flow or LV wall motion.11 The need for these newer parameters was driven by the U-shaped relationship between the ratio of early-to-late transmitral flow velocity (E/A) with filling pressure and facilitated by technical developments in echocardiography.

Engineering insight, as well as a modelling study,12 suggests that some new markers of diastolic function, such as colour M-mode flow propagation velocity (Vp), are affected by LV dilation or presence of concentric hypertrophy. This implies that values of Vp considered normal in the setting of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) may be abnormal in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). For these reasons, we conducted a study to assess the way diastolic function parameters behave in the presence of altered LV volume and mass (both represented by LV volume/mass ratio) as seen in DCM or HCM. A primary aim of this study was to determine whether LV volume/mass ratio affects parameters of diastolic function.

Methods

Study population

Patients

To identify patients, we first cross-referenced a list of patients for which the echocardiography report stated the presence of hypertrophic (n = 810) or non-ischaemic DCM (n = 940) with a database of 12 768 Cleveland Clinic patients in whom echocardiography was performed on a Vivid 7 ultrasound machine (GE Medical, Milwaukee, WI, USA) in a period of January 2004–December 2007. The medical records were then checked to ascertain that inclusion criteria were satisfied as follows. HCM was diagnosed by the echocardiographic demonstration of a hypertrophied, non-dilated LV in the absence of other acquired or congenital heart disease. Non-ischaemic DCM was diagnosed in a presence of dilated left ventricle with ejection fraction <40%, no prior history of myocardial infarction, and no significant coronary artery stenosis on coronary angiography. DCM subjects were subcategorized according to QRS width into DCM with narrow QRS (<130 ms, DCM-n) or DCM with wide QRS (≥130 ms, DCM-w). Finally, patients were selected if acquired echocardiography study was of a satisfactory quality (35 from 55 HCM subjects, 29 from 40 DCM-n subjects, and 27 from 46 DCM-w subjects) as indicated in Data acquisition section.

All patients were clinically stable and in normal sinus rhythm. Patients were excluded for significant valvular heart disease (mitral regurgitation was allowed if it was less than moderate degree), pacemaker implantation, prior cardiac surgery, or percutaneous LV septal reduction procedure. According to aforementioned criterions, all patients were identified (n = 94, age 53 ± 14 years, range 22–79 years).

Control subjects

Our healthy controls were selected from our database of 102 normal subjects. These subjects volunteered for an echocardiography study after being informed through information panels located throughout Cleveland Clinic main campus. Subjects were declared healthy after normal electrocardiogram and thorough medical history and physical examination (including testing of fasting blood glucose and cholesterol fraction levels) revealed no cardiovascular disease. None of them reported taking cardiac medications (except aspirin). To assess the impact of aging on diastolic function, we first randomly sampled healthy controls out of this population (n = 74, average age 41 ± 15 years, range 18–76 years). This sample size yields a two-sided power (beta) of 80% to detect a correlation of 0.325 or greater at the alpha level of <0.05. To assess the differences in diastolic function between healthy controls and patients with cardiomyopathy, we age-matched these two groups. For this purpose, we sub-sampled our 74 healthy controls by, first, limiting the selection by having the age range identical to the age range of patient sample, and then drawing all possible samples with the size of n > 40 subjects. The selected sample had a closest mean and SD to the patients' sample (n = 44, age 50 ± 13 years, range 22–76 years, P=n.s. for the comparison between patients and controls).

Institutional Review Board of Cleveland approved for the database search. All subjects gave written informed consent for the participation in respective prospective studies.

Data acquisition

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography was performed with a Vivid 7 ultrasound machine (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and M3S/M4S probe. Standard views, including apical four-chamber, apical two-chamber, apical long-axis, and parasternal long- and short-axis views, were obtained. Short-axis views were acquired at the mitral valve and apical LV levels (absence of right ventricle and papillary muscle for apical short-axis). Second-harmonic images were acquired with high frame rate B-mode scans (40–90 frames/s) for speckle tracking imaging. Pulsed-wave Doppler interrogation of the transmitral flow and LV outflow tract (LVOT), and colour M-mode of intraventricular filling were acquired from apical four-chamber view. Two-dimensional tissue Doppler image followed by pulsed-wave assessment of the septal and lateral mitral annulus (Ea) were also obtained in the apical four-chamber view. All images were stored in a digital cine-loop format for off-line analysis.

Data analysis

LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, ejection fraction, and left atrial end-systolic volume were calculated by a modified Simpson's biplane method from apical imaging planes. LV mass was calculated by the area–length formula recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography.13 LV transverse diameter in end-systole was calculated from the LV short-axis area at papillary muscle level using equation LV diameter=2×2×(LV area/3.14)0.5. All cardiac chamber volumes and mass measures were indexed to body surface area. We assumed that LV volume at the beginning of filling (i.e. at the end of isovolumic relaxation) could be represented by end-systolic volume. Thus end-systolic volume/mass ratio was taken to represent a feature of LV geometry at the beginning of LV filling.14

Peak velocity of early (E) and late (A) wave of transmitral flow and E-wave deceleration time (DT) were measured from the pulsed-wave Doppler obtained at the tip of mitral leaflets. Aortic valve closure and mitral valve opening times were obtained from pulsed-wave Doppler signal properly positioned at LVOT to calculate LV IVRT. We derived two parameters of intraventricular filling, flow propagation velocity (Vp), and the peak early diastolic intraventricular pressure gradient (IVPG), from colour M-mode at LV inflow.15 Ea was the average of septal and lateral annulus velocities. All values were averaged from three cardiac cycles.

Rotational rates of the LV base and apex were measured from short-axis echocardiographic images by speckle tracking (EchoPac PC software, GE Medical) as described previously.16 In brief, the instantaneous difference of basal and apical rotational rates was calculated, yielding the twisting rate (TwR) curve. Peak TwR and untwisting rate (UntwR) were then defined by peak positive and negative values, respectively. Twist was the peak value obtained by temporal integration of TwR curve. Two cardiac cycles of both basal and apical data were analysed and the data were averaged.

The time constant of isovolumic pressure decay with a zero asymptote assumption (τ0) was estimated using the following equation:17

where P is systolic blood pressure and PCWP is mean PCWP.9,18 In HCM subjects with LVOT obstruction, peak LV systolic pressure was estimated by adding the peak LVOT gradient to sphygmomanometric systolic blood pressure. Mean PCWP was estimated by averaging PCWP obtained by two previously described estimation methods (i.e. E/Vp and E/Ea)7,8,19 to increase the accuracy of the estimation.

To assess the accuracy of τ0 estimation, we additionally analysed the data from a prospective study of echocardiography during acutely decompensated systolic heart failure, in which filling pressures were routinely monitored by a pulmonary artery catheter. From this study, we randomly selected 34 subjects (16 of whom with DCM) with 56 echocardiography studies performed within 30 min of PCWP measurement. We used these data to compare τ0 calculated using measured PCWP vs. τ0 estimated from echocardiography only data. We also identified nine of our patients with HCM had filling pressures measured invasively within 48 h of echocardiography, without any change of cardioactive medications in the meantime. The correlation of τ0 estimated by echocardiography with τ0 calculated from invasively recorded filling pressures had an of r = 0.70, P < 0.0001 (r = 0.71 for systolic heart failure subjects and r = 0.84 for HCM patients), while the average difference between two methods was 0.24 ms [95% confidence interval (CI) −2.76 to 3.24] with 95% limits of agreement (LOA) −23.56 ms (95% CI −18.7 to −28.46) to 24.04 ms (95% CI 18.9–29.1). Taken together, these data imply that our τ0 estimate is physiologically relevant even with PCWP estimation error.

Validation of LV mass estimation by echocardiography

We already validated estimation of LV mass by echocardiography using magnetic resonance imaging as a ‘gold standard’ in 16 healthy controls.20 We further assessed 10 HCM patients (eight with asymmetric septal hypertrophy, one with concentric HCM, and one with proximal septal bulge, mean age 30 ± 9 years) and seven patients with DCM (all with EF < 40%, mean age 57 ± 20 years), all of whom had a magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography studies performed within 7 days. In a total group of 33 patients, a bias between two methods was 9.7% (95% CI −1 to 21%), with 95% LOA of −22% (95% CI −41 to −3%), and 42% (95% CI 23–61%). Specifically, it was 6.5% (95% LOA of −26 to 39%) in HCM subjects and 20% (95% LOA of −17 to 57%) in DCM subjects (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1).

Reproducibility

To assess intra- and inter-observer variability of LV volumes and mass, nine randomly chosen data sets (corresponding to ∼5% of our study population) were measured twice, after a time interval of >1 month, by the same observer and, at that time, also by a second observer blinded to the measurements of the first observer. Inter- and intra-observer variabilities were quantified as the difference and percent difference (with a denominator a mean of the two measurements) between the two measurements along with their 95% LOA.21 Intra-observer variability for LV end-diastolic volume, end-systolic volume, and mass was 0.9 mL (95% CI −9 to 7 mL) [95% LOA −19 mL (95% CI −35 to −5 mL) to 17 mL (95% CI 3–31 mL)], 0.5 mL (95% CI −3 to 4 mL) [ 95% LOA −21 (95% CI −45 to 3 mL) to 22 mL (95% CI −2 to 46 mL)], and 2.5 g (95% CI −19 to 24 g) [95% LOA −30 (95% CI −68 to 8 g) to 35 (95% CI −3 to 73 g)]. For the same three parameters, percent intra-observer variability was 0.2% (95% CI −2.7 to 2.3%) [LOA −4 (95% CI −8 to 0%) to 3% (95% CI 0–8%)], 0.5% (95% CI −3.2 to 4.2%) [95%LOA −5 (95% CI −11 to 1%) to 6% (95% CI 0–12%)], and −0.1% (95% CI −2.7 to 2.5%) [95% LOA −4 (95% CI −9 to 1%) to 4% (95% CI −1 to 8%)]. Inter-observer variability for LV end-diastolic volume, end-systolic volume, and mass was 7.8 mL (95% CI −19 to 35 mL) [95% LOA −33 (95% CI −80 to 14 mL) to 49 mL (95% CI 2 to 96 mL)], −2.3 mL (95% CI −9 to 5 mL) [95% LOA −13 (95% CI −25 to −1 mL) to 8 mL (95% CI −4 to 20 mL)], and −5 g (95% CI −22 to 12 g) [95% LOA −31 g (95% CI −61 to −1 g) to 21 g (95% CI −9 to 51 g)]. For the same three parameters, percent inter-observer variability was 1.3% (95% CI −1.9 to 4.5%) [LOA −4 (95% CI −9 to 2%) to 6% (95% CI 0–12%)], −0.7% (95% CI −3.0 to 1.6%) [95%LOA −4 (95% CI −8 to 0%) to 3% (95% CI −1 to 7%)], and −0.5% (95% CI −2.6 to 1.6%) [95% LOA −4 (95% CI −7 to 0%) to 3% (95% CI −1 to 6%)] (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2).

Statistical analysis

Values are shown as mean ± SD or percentage when appropriate. Between–group comparisons for individual parameters were done by analysis of variance followed by post hoc Tukey Honest Significant Difference test to correct for multiple comparisons. Correlation between diastolic parameters (Vp, IVPG, Ea, UntwR, and DT) and LV volume/mass ratio was performed by simple linear regression. We also assessed within–group correlations between diastolic parameters and LV geometry by analysis of covariance, with patient groups as an independent predictor and LV volume/mass ratio as a covariate.

Echocardiographic parameters of early diastolic function are affected by preload and relaxation. Since transmitral E-wave velocity is fully determined by preload and relaxation and τ0 is a direct measure of relaxation, we postulated that by correcting for transmitral E-wave velocity and τ0 we would eliminate effects of preload and relaxation on echocardiographic diastolic function parameters.22,23 Therefore, to further study the interaction between preload, relaxation, and LV volume/mass ratio on diastolic function we performed a multiple regression using transmitral E-wave velocity, τ0, and LV volume/mass ratio (with variance stabilized by taking a cubed root) as predictors. As dependent variables, we tested following five diastolic parameters of interest: Vp, IVPG, Ea, UntwR, and DT. Then, using regression analysis results, we corrected each diastolic parameter of interest for the values of transmitral E-wave velocity and τ0 by equation:

Here, E is E-wave velocity, τ is τ0, and βE and βτ are corresponding regression coefficients, while subscript i denotes values of individual patient. Linear regression of these corrected diastolic parameters with LV volume/mass ratio is identical to partial correlation data obtained from multiple linear regressions. A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests, except for the results of linear regression analyses where P < 0.01 was considered significant to correct for multiple comparisons (n = 5) between LV volume/mass ratio and diastolic parameters.

Results

Subjects' clinical characteristics and basic echocardiographic findings were presented in Table 1. In HCM patients, the hypertrophy type was concentric in 15, asymmetric septal in 14, and septal bulge in six patients (four of which had also distal septal and/or posterior wall hypertrophy). Eleven HCM patients had resting LVOT gradient ≥30 mmHg (range 33–115), with its magnitude correlating with LV mass (r = 0.54, P = 0.0008). Of note, LV volume mass ratio correlated strongly with LV end-systolic transverse diameter (r = 0.85, P < 0.0001), a more traditional parameter of LV size.

Table 1.

Clinical and echocardiographic findings of all subjects

| Control (n = 44) | HCM (n = 35) | DCM-n (n = 29) | DCM-w (n = 27) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 50 ± 13 | 47 ± 14 | 54 ± 12 | 59 ± 12§* | 0.001 |

| Male (n) | 16 | 24 | 19 | 18 | 0.01 |

| HR (b.p.m.) | 68 ± 11 | 58 ± 11 | 75 ± 16§‡ | 72 ± 13§‡ | 0.002 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 120 ± 14 | 124 ± 18 | 115 ± 21 | 114 ± 18 | 0.07 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 69 ± 9 | 73 ± 12 | 68 ± 14 | 70 ± 13 | 0.3 |

| NYHA class | 1 | 2 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.001 |

| LVESV (mL) | 32 ± 11 | 38 ± 17 | 127 ± 61*† | 178 ± 98*†¶ | <0.001 |

| LVEDV (mL) | 86 ± 24 | 103 ± 37 | 179 ± 73*† | 235 ± 119*†¶ | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 63 ± 7 | 64 ± 7 | 31 ± 8*† | 26 ± 8*† | <0.001 |

| LVMI (gm/m2) | 60 ± 32 | 119 ± 39 | 112 ± 22 | 110 ± 28 | <0.001 |

| LV volume/mass ratio (mL/gm) | 0.32 ± 0.09* | 0.16 ± 0.06* | 0.60 ± 0.20* | 0.80 ± 0.30* | <0.001 |

| QRS width (ms) | 90 ± 18 | 108 ± 22 | 106 ± 12 | 156 ± 18*†¶ | <0.001 |

DCM-n(-w), dilated cardiomyopathy with narrow(wide) QRS complex width; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional classification; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Last column represents overall significance level by the analysis of variance. Post hoc multiple group comparisons are shown as: *P<0.001 vs. control; §P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.001 vs. HCM; ‡P < 0.05 vs. HCM; ¶P < 0.05 vs. DCM-n.

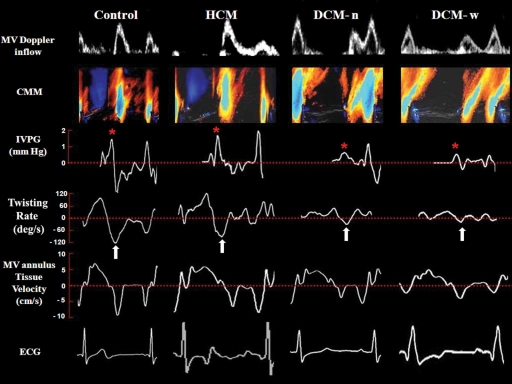

Diastolic echocardiographic parameters in each group of subjects are shown in Table 2. Although transmitral E-wave velocity and E/A ratio were similar across the groups, all other diastolic parameters showed significant between–group differences. Examples of some important parameters from a representative case in each group of subjects were depicted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Important diastolic parameters in each group of subjects

| Control (n = 44) | HCM (n = 35) | DCM-n (n = 29) | DCM-w (n = 27) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-wave velocity (cm/s) | 71 ± 17 | 80 ± 21 | 76 ± 26 | 82 ± 32 | 0.8 |

| E/A ratio | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 0.6 |

| DT (ms) | 204 ± 42 | 231 ± 70 | 173 ± 61† | 167 ± 68† | <0.001 |

| Vp (cm/s) | 62 ± 13 | 60 ± 16 | 37 ± 9*† | 35 ± 12*† | <0.001 |

| IVPG (mmHg) | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.4*† | 1 ± 0.4*† | <0.001 |

| Ea (cm/s) | 11.0 ± 2.4 | 7.1 ± 2.7*† | 5.5 ± 1.9*† | 5.3 ± 1.4*† | <0.001 |

| Untwisting rate (°/s) | 113 ± 48 | 93 ± 55 | 48 ± 30*† | 21 ± 15*† | <0.001 |

| τ0 (ms) | 35.6 ± 9.2 | 42.9 ± 12.0*† | 56.3 ± 18.0*† | 65.5 ± 19.1*† | <0.001 |

| LAVI (mL/m2) | 19.0 ± 6.8 | 29.8 ± 9.4* | 37.4 ± 17.7* | 37.5 ± 15.6* | <0.001 |

E, early transmitral inflow velocity; E/A ratio, ratio of early-to-late transmitral flow velocity; DT, deceleration time; Vp, mitral flow propagation velocity; IVPG, early diastolic intraventricular pressure gradient; Ea, averaged mitral annulus velocity; τ0, time constant of isovolumic pressure decay with a zero asymptote assumption; LAVI, left atrial volume index.

Other abbreviations and significance as in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of LV diastolic function from each group of subjects. While pulse-wave Doppler (PW) of the LV inflow in all three patient groups shows a pattern of delayed relaxation (first row), flow propagation by CMM of the LV inflow (second row), corresponding IVPG (third row,*), and UntwR (fourth row, arrow) were close to normal in HCM subject, but depressed in DCM subjects. In contrast, Ea was depressed in all diseased subjects. Tracings are timed to the electrocardiogram (ECG) that appears in a lowest panel.

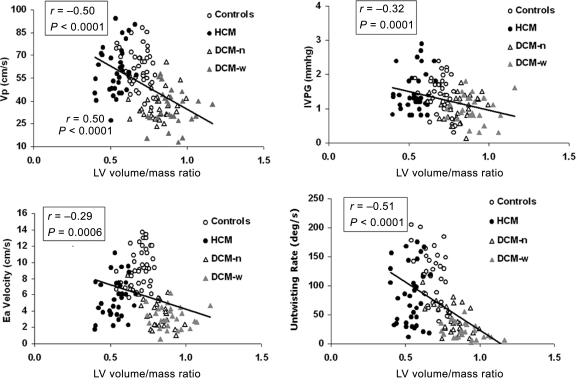

Effect of left ventricular volume/mass ratio on diastolic function

LV volume/mass ratio showed significant inverse relationship with unadjusted Vp, IVPG, Ea, and UntwR (Figure 2). As LV volume/mass ratio showed small variance within each patient group (Table 1), only UntwR showed significant within–group correlation with LV volume/mass ratio (r = −0.28, P = 0.002).

Figure 2.

Correlation between LV volume/mass ratio and diastolic parameters derived from LV wall motion and intraventricular flow. Correlation between LV end-systolic volume/mass ratio (LV volume/mass ratio) and flow propagation velocity (Vp; panel A), early diastolic intraventricular pressure gradient (IVPG; panel B), averaged early diastolic mitral annulus velocity (Ea; panel C), and peak untwisting rate (UntwR; panel D), are shown.

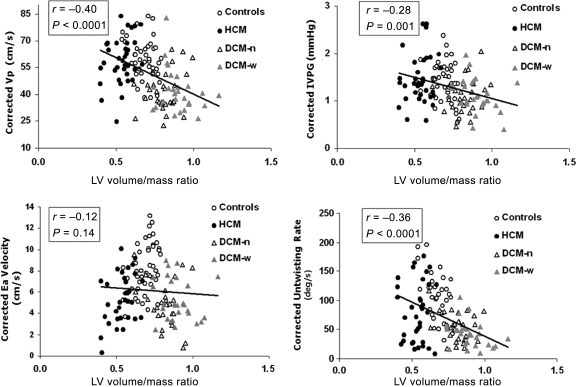

After adjusting for the impact of E and τ0 by multiple regressions, LV volume/mass ratio remained a strong independent predictor of Vp, IVPG, UntwR, and DT (P ≤ 0.001 for all) (Table 3 and Figure 3). In contrast, LV volume/mass ratio did not influence Ea.

Table 3.

Linear regression models for predicting diastolic parameters of interest

| Diastolic parameters | Predictors | Multiple R | β-Standardized coefficients (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vp | 0.71 | |||

| E | 0.29 (0.16 to 0.42) | <0.001 | ||

| τ0 | −0.40 (−0.55 to −026) | <0.001 | ||

| LV volume/mass ratio | −0.36 (−0.50 to −0.21) | <0.001 | ||

| IVPG | 0.61 | |||

| E | 0.46 (0.31–0.60) | <0.001 | ||

| τ0 | −0.26 (−0.42 to −0.11) | 0.005 | ||

| LV volume/mass ratio | −0.26 (−0.42 to −0.10) | 0.009 | ||

| UntwR | 0.67 | |||

| E | −0.02 (−0.17 to 0.13) | 0.81 | ||

| τ0 | −0.34 (−0.51 to −0.18) | <0.001 | ||

| LV volume/mass ratio | −0.35 (−0.52 to 0.18) | 0.001 | ||

| DT | 0.54 | |||

| E | −0.27 (−0.42 to −0.12) | 0.001 | ||

| τ0 | −0.21 (−0.38 to −0.04) | 0.009 | ||

| LV volume/mass ratio | −0.33 (−0.50 to −0.16) | <0.001 | ||

| Ea | 0.66 | |||

| E | 0.17 (0.03–0.32) | 0.02 | ||

| τ0 | −0.59 (−0.74 to −0.42) | <0.001 | ||

| LV volume/mass ratio | 0.01 (−0.15 to 0.17) | 0.93 |

CI, confidence interval; DT, early diastolic deceleration time of left ventricular inflow; E, early transmitral inflow velocity; Ea, averaged early diastolic mitral annulus velocity; IVPG, early diastolic intraventricular pressure gradient; τ0, time constant of isovolumic pressure decay with a zero asymptote assumption; UntwR, peak untwisting rate, and Vp, transmitral flow propagation velocity.

Figure 3.

Correlation between LV volume/mass ratio and corrected diastolic parameters derived from LV wall motion and intraventricular flow. Abbreviations and layout as in Figure 2. Each of the four presented diastolic parameters was corrected for the values of transmitral E-wave velocity and tau0 (τ0) using multiple regression equation data as marked by asterisk (*). R- and P-values represent the values of partial correlation from multiple regressions.

As a resting LVOT gradient in HCM may indicate a presence of asymmetric hypertrophy, we repeated analysis after excluding 11 subjects with resting LVOT gradient of >30 mmHg. In this setting, LV volume/mass ratio was again a strong independent predictor of Vp (partial r = −0.47, P < 0.0001), IVPG (partial r = −0.34, P = 0.0001), UntwR (partial r = −0.44, P < 0.0001), and DT (partial r = −0.36, P = 0.0001). It also had a weak impact on Ea (partial r = −0.19, P = 0.03), probably reflecting a decreased sample size in the lower portion of distribution of LV volume/mass ratio values.

Effects of ageing

In a group of 74 healthy controls, age was inversely correlated with LV volume/mass ratio (r = −0.33, P = 0.004), indicating expected association of aging and concentric remodelling. To assess if senescence affects diastolic parameters independently of the changes in load and relaxation that may occur concomitantly with increasing age, we performed a multiple regression analysis of the impact of age, E, τ, and LV volume/mass ratio on diastolic parameters. After controlling for other independent predictors, age did not independently affect Vp, IVPG, DT, and UntwR (P = n.s. for all four), whereas it correlated inversely with Ea (partial r = −0.53, P < 0.0001). Furthermore, in the same analysis, volume/mass ratio showed a weak correlation with corrected Ea (partial r = 0.27, P = 0.02), but showed inverse correlation with corrected UntwR (partial r = −0.45, P<0.0001), with a trend towards inverse correlation with corrected Vp and IVPG (partial r = −0.22 P = 0.07 and partial r = −0.17, P = 0.15, respectively).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that Vp, IVPG, Ea, and UntwR are strongly influenced by relaxation rate10,18,24 and displayed weak to moderate preload sensitivity.18,25–29 Here, we show that Vp, IVPG, UntwR, and DT were independently influenced by LV volume/mass ratio. In contrast, Ea was influenced by relaxation and preload only. In practical terms, these data indicate that depressed values of Vp, IVPG, and UntwR when observed in HCM reflect deeper abnormalities in relaxation than in DCM.

Computer modelling has shown that, in a normal ventricle, a doughnut-shaped vortex forms around the column of mitral inflow and then travels downward towards the apex.30 Increased LV size in DCM should increase vortex size because of a larger distance between blood column and LV walls. Large vortices dissipate energy that results in a loss of velocity of flow column. Baccani et al.12 used fluid dynamics model of DCM to prove that LV dilation indeed decreases Vp. Furthermore, they have shown that this is associated with the initial vortex staying attached to the mitral valve. Although they have not assessed IVPG, it can be surmised that it also decreases. By analogy, effects of LV volume/mass ratio in HCM should be opposite, because boundary effects of LV do not allow energy dissipation. Here, we corroborate that parameters of intraventricular filling, Vp, and IVPG, are indeed decreased in DCM but frequently preserved in HCM (Table 2).

LV volume/mass ratio had influence on UntwR but not Ea, although they both represent early diastolic wall motion (Figure 3). The impact of LV volume/mass ratio on UntwR can be explained through its link with LV twist. LV twist is generated because subepicardial myocytes, oriented in a left-handed helix, have a lever advantage over subendocardial myocytes that run in a right-handed helix.31 As ventricles with HCM have a larger distance between endo- and epicardial layers, the subepicardial helix becomes even more dominant,31 twisting more forcefully the apex in the counterclockwise and the base in the clockwise direction.32 This increased twist allows for higher peak UntwRs. Thus, despite the fact that HCM is characterized by prolonged time to peak UntwR and worsened relaxation33 which both decrease UntwR, this is offset by larger LV thickness, leading to higher UntwR than in DCM assuming similar level of relaxation impairment. In contrast, it is puzzling that LV volume/mass ratio does not influence Ea velocity. The presence of LV hypertrophy, independent of whether it is concentric (as in HCM) or eccentric (as in DCM), is sufficient to decrease Ea.

Another factor that can influence diastole is intraventricular conduction delay (IVCD) as represented by QRS width. IVCD may lead to dyssynchronous relaxation of LV regions by increasing dispersion of repolarization. However, in DCM, IVCD is predictive of disease severity,34,35 and thus it is difficult to dissociate effects of IVCD from that of severe DCM. Our study indicated that, while diastolic function parameters worsen with a degree of IVCD in a univariate analysis, after adjustment for LV volume/mass ratio, a loss of diastolic suction and ventricular recoil in DCM was independent of the presence of IVCD.

Clinical implications and future directions

Although new diastolic function parameters are being proposed continuously, only Ea and Vp have been tested for their prognostic value. Some studies showed that Ea has incremental predictive power over and above clinical and standard echocardiography data,36,37 our group, albeit in a smaller study, failed to confirm the predictive value of either Ea or Vp.38 On the other hand, prognostic value of Ea and Vp improves once they corrected for E-wave velocity.38,39 Our data imply that Vp, as well as IVPG, UntwR, and DT, have to be additionally corrected for underlying LV geometry. These findings are especially relevant, if clinical trials are planned to test these diastolic parameters.

An obstacle for a wider use of diastolic parameters, we assessed here is that they can be generated only by complex and time-consuming post-processing. Currently, only Ea can be readily derived from most ultrasound machines. However, this obstacle could be easily overcome, if the manufacturers of echo devices incorporate post-processing algorithms into standard ultrasound machines. Given a current level of development, this should be a simple engineering feat.

Limitations

We have not assessed LV volumes and mass using three-dimensional methods such as magnetic resonance or three-dimensional echocardiography, which may have introduced errors in the estimation of LV volume/mass ratio, especially in HCM patients. PCWP and τ0 were estimated by non-invasive means, which increased uncertainty in the estimation of the magnitude of the effect of relaxation on diastolic parameters. To overcome this, we studied a large patient population. The assessment of τ0 by our method has been tested in a variety of patient populations, but not specifically in HCM. However, basic mathematical principles should be universal to all patients. Ample evidences corroborate preload sensitivity of E-wave, especially when controlled for relaxation.6,10 As our regression model always included relaxation, we believe that E-wave velocity well reflected the impact of preload. The most sensitive part of our τ0 estimation is the calculation of PCWP estimate. Although several studies indicated that E ‘corrected’ by Ea or Vp is robust enough to detect changes in PCWP at a group level, this relationship seems poorer in the setting of LV hypertrophy.40 However, our clinical data show the precision is satisfactory for making accurate τ0 estimation. It is uncertain whether our findings can be generalized to other patient populations, such as restrictive cardiomyopathy. Infiltrative processes that occur in amyloidosis or Fabry's disease affect both wall thickness and structure, thus dramatically changing passive biomechanical characteristics of muscle tissue. Our aim was to assess whether a change of relative thickness of LV wall with preserved myocardial tissue characteristics affects diastolic function parameters. Additionally, HCM patients with LV outflow obstruction frequently display septal bulge or sigmoid shape of the septum that may have more impact on LV inflow than predicted from measuring of LV volume/mass ratio. In our series of HCM patients, exclusion of patients with significant LVOT gradient did not dramatically change the results.

Conclusions

LV volume/mass ratio correlated with flow propagation velocity, early diastolic IVPGs, and UntwR even after adjusting for preload and relaxation. This indicates that these diastolic function parameters have a previously unrecognized source of variability that is independent of both intrinsic diastolic function (characterized by τ) and filling pressures. Because it is easy to calculate and clinically meaningful, LV volume/mass ratio should be considered when assessing patients suspected of LV diastolic dysfunction regardless of LV systolic function.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal Online.

Funding

Dr A.B. was funded by Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand. This manuscript was supported through grants by National Institutes of Health grant AG17479-02, National Space Biomedical Research Institute through NASA NCC 9-58 (Houston, TX), Department of Defense (Ft. Dietrick, Md, USAMRMC grant no. 02360007), National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, General Clinical Research Center (grant MO1 RR-018390), and National American Heart Association grant 0235172N.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Xie GY, Berk MR, Smith MD, Gurley JC, DeMaria AN. Prognostic value of Doppler transmitral flow patterns in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:132–139. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richartz BM, Werner GS, Ferrari M, Figulla HR. Comparison of left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and mild heart failure vs. those with severe heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:390–394. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02495-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillis GS, Moller JE, Pellikka PA, Gersh BJ, Wright RS, Ommen SR, Reeder GS, Oh JK. Noninvasive estimation of left ventricular filling pressure by E/e' is a powerful predictor of survival after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rihal CS, Nishimura RA, Hatle LK, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. Systolic and diastolic dysfunction in patients with clinical diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy: relation to symptoms and prognosis. Circulation. 1994;90:2772–2779. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.6.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson H, Lonn E, Edner M, Baruch L, Lang CC, Morton JJ, Ostergren J, McKelvie RS. Diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved systolic function: need for objective evidence: results from the CHARM Echocardiographic Substudy-CHARMES. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagueh SF, Lakkis NM, Middleton KJ, Spencer WH, III, Zoghbi WA, Quinones MA. Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressures in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1999;99:254–261. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia MJ, Ares MA, Asher C, Rodriguez L, Vandervoort P, Thomas JD. An index of early left ventricular filling that combined with pulsed Doppler peak E velocity may estimate capillary wedge pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:448–454. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, Miller FA, Oh JK, Redfield MM, Tajik AJ. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparative simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study. Circulation. 2000;102:1788–1794. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scalia GM, Greenberg NL, McCarthy PM, Thomas JD, Vandervoort PM. Noninvasive assessment of the ventricular relaxation time constant (τ) in humans by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1997;95:151–155. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia MJ, Smedira NG, Greenberg NL, Main M, Firstenberg MS, Odabashian J, Thomas JD. Color M-mode Doppler flow propagation velocity is a preload insensitive index of left ventricular relaxation: animal and human validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas JD, Popovic ZB. Assessment of left ventricular function by cardiac ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2012–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baccani B, Domenichini F, Pedrizzetti G, Tonti G. Fluid dynamics of the left ventricular filling in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Biomech. 2002;35:665–671. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria AN, Devereaux R, Feigenbaum H, Gutgesell H, Reichek N, Sahn D, Schnittger I, Silverman NH, Tajik J. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2:358–367. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corin WJ, Sutsch G, Murakami T, Krogmann ON, Turina M, Hess OM. Left ventricular function in chronic mitral regurgitation: preoperative and postoperative comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:113–121. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00354-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg NL, Vandervoort PM, Firstenberg MS, Garcia MJ, Thomas JD. Estimation of diastolic intraventricular pressure gradients by Doppler M-mode echocardiography. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2507–H2515. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Notomi Y, Lysyansky P, Setser RM, Shiota T, Popovic ZB, Martin-Miklovic MG, Weaver JA, Oryszak SJ, Greenberg NL, White RD, Thomas JD. Measurement of ventricular torsion by two-dimensional ultrasound speckle tracking imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:2034–2041. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas JD, Flachskampf FA, Chen C, Guererro JL, Picard MH, Levine RA, Weyman AE. Isovolumic relaxation time varies predictably with its time constant and aortic and left atrial pressures: implications for the noninvasive evaluation of ventricular relaxation. Am Heart J. 1992;124:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90416-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popovic ZB, Prasad A, Garcia MJ, Arbab-Zadeh A, Borowski A, Dijk E, Greenberg NL, Levine BD, Thomas JD. Relationship among diastolic intraventricular pressure gradients, relaxation, and preload: impact of age and fitness. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1454–H1459. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00902.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Firstenberg MS, Levine BD, Garcia MJ, Greenberg NL, Cardon L, Morehead AJ, Zuckerman J, Thomas JD. Relationship of echocardiographic indices to pulmonary capillary wedge pressures in healthy volunteers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1664–1669. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popovic ZB, Sun JP, Yamada H, Drinko J, Mauer K, Greenberg NL, Cheng Y, Moravec CS, Penn MS, Mazgalev TN, Thomas JD. Differences in left ventricular long-axis function from mice to humans follow allometric scaling to ventricular size. J Physiol. 2005;568:255–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas JD, Zhou J, Greenberg N, Bibawy G, McCarthy PM, Vandervoort PM. Physical and physiological determinants of pulmonary venous flow: numerical analysis. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2453–H2465. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas JD, Newell JB, Choong CY, Weyman AE. Physical and physiological determinants of transmitral velocity: numerical analysis. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H1718–H1731. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.5.H1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choong CY, Abascal VM, Thomas JD, Guerrero JL, McGlew S, Weyman AE. Combined influence of ventricular loading and relaxation on the transmitral flow velocity profile in dogs measured by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1988;78:672–683. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagueh SF, Sun H, Kopelen HA, Middleton KJ, Khoury DS. Hemodynamic determinants of the mitral annulus diastolic velocities by tissue Doppler. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:278–285. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad A, Popovic ZB, Arbab-Zadeh A, Fu Q, Palmer D, Dijk E, Greenberg NL, Garcia MJ, Thomas JD, Levine BD. The effects of aging and physical activity on Doppler measures of diastolic function. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1629–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacques DC, Pinsky MR, Severyn D, Gorcsan J., III Influence of alterations in loading on mitral annular velocity by tissue Doppler echocardiography and its associated ability to predict filling pressures. Chest. 2004;126:1910–1918. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Firstenberg MS, Greenberg NL, Main ML, Drinko JK, Odabashian JA, Thomas JD, Garcia MJ. Determinants of diastolic myocardial tissue Doppler velocities: influences of relaxation and preload. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:299–307. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong SJ, Hees PS, Huang WM, Buffer SA, Jr, Weiss JL, Shapiro EP. Independent effects of preload, afterload, and contractility on left ventricular torsion. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H1053–H1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y, Oertel H, Schenkel T. Fluid-structure coupled CFD simulation of the left ventricular flow during filling phase. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:567–576. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-4388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingels NB, Jr, Hansen DE, Daughters GT, II, Stinson EB, Alderman EL, Miller DC. Relation between longitudinal, circumferential, and oblique shortening and torsional deformation in the left ventricle of the transplanted human heart. Circ Res. 1989;64:915–927. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagel E, Stuber M, Burkhard B, Fischer SE, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P, Hess OM. Cardiac rotation and relaxation in patients with aortic valve stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:582–589. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Notomi Y, Martin-Miklovic MG, Oryszak SJ, Shiota T, Deserranno D, Popovic ZB, Garcia MJ, Greenberg NL, Thomas JD. Enhanced ventricular untwisting during exercise: a mechanistic manifestation of elastic recoil described by Doppler tissue imaging. Circulation. 2006;113:2524–2533. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.596502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unverferth DV, Magorien RD, Moeschberger ML, Baker PB, Fetters JK, Leier CV. Factors influencing the one-year mortality of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu CM, Zhang Q, Yip GW, Lee PW, Kum LC, Lam YY, Fung JW. Diastolic and systolic asynchrony in patients with diastolic heart failure: a common but ignored condition. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang M, Yip GW, Wang AY, Zhang Y, Ho PY, Tse MK, Lam PK, Sanderson JE. Peak early diastolic mitral annulus velocity by tissue Doppler imaging adds independent and incremental prognostic value. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:820–826. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02921-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikitin NP, Loh PH, Silva R, Ghosh J, Khaleva OY, Goode K, Rigby AS, Alamgir F, Clark AL, Cleland JG. Prognostic value of systolic mitral annular velocity measured with Doppler tissue imaging in patients with chronic heart failure caused by left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Heart. 2006;92:775–779. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.067140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Troughton RW, Prior DL, Frampton CM, Nash PJ, Pereira JJ, Martin M, Fogarty A, Morehead AJ, Starling RC, Young JB, Thomas JD, Lauer MS, Klein AL. Usefulness of tissue doppler and color M-mode indexes of left ventricular diastolic function in predicting outcomes in systolic left ventricular heart failure (from the ADEPT study) Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang HY, Cauduro SA, Pellikka PA, Bailey KR, Grossardt BR, Yang EH, Rihal C, Seward JB, Miller FA, Abraham TP. Comparison of usefulness of echocardiographic Doppler variables to left ventricular end-diastolic pressure in predicting future heart failure events. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:866–871. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geske JB, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR. Evaluation of left ventricular filling pressures by Doppler echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: correlation with direct left atrial pressure measurement at cardiac catheterization. Circulation. 2007;116:2702–2708. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.