During the past 16 months, horses have been immunized in our laboratories against the lymphoid tissue of both dogs and man. From the beginning, it was evident that the resultant equine antibodies had substantial lymphopenic and immunosuppressive qualities, as proved after administration of the horse serum or plasma to both dogs which had and those which had not received transplants. However, excessive toxicity precluded the use of such biologic materials in human immunosuppressive regimens. Furthermore, the antibody titers in the early preparations were so low that large volumes were necessary for an effect, making administration impractical.

Ultimately, means were found to raise very high titers of antibody against either human or dog lymphoid tissue. The active principle was found to be in the gamma G globulin and in other immunoglobulin fractions. A protein derivative which included these components was separated which was of such potency that it caused lymphopenia in both dogs and man when given subcutaneously or intramuscularly in small volumes. This product has been used by us for immunosuppression of a number of patients after renal homotransplantation (26). However, the present report is not concerned with the protection afforded by these products to homografts but rather with observations relevant to horse immunization, methods of purification of globulin from horse serum, and the physiologic and immunologic responses of both dogs and man after injection with these materials.

Methods

Immunization

Ten horses which weighed 400 to 500 kilograms were inoculated subcutaneously with canine lymphoid tissue. Spleen was the only source of antigen in 4 animals, and the other 6 were injected with both lymph nodes and spleen. The number of sacrificed canine donors for the individual horses ranged from 10 to 30.

Two other horses weighing 425 and 610 kilograms were inoculated with human lymphoid tissue from 6 and 21 cadaveric donors respectively after a maximum postmortem delay of 150 minutes. One of the 2 animals received lymph nodes, thymus, and spleen, and the other received only spleen.

Both the human and canine tissues were prepared in the same way. The lymph nodes and thymuses were washed in chilled normal saline immediately after extirpation. The spleens were perfused through the splenic artery with 2 to 6 liters of chilled lactated Ringer's solution. The lymphoid tissue was then ground up and passed through progressively finer mesh stainless steel filters, the last denier being 40. The cells in the final suspension were counted, the type of cells was determined with differential counts after Wright staining, and the incidence of cell viability estimated after staining with trypan blue. The cell population of the final saline suspension consisted of 85 to 99 per cent lymphocytes, 1 to 15 per cent granulocytes, and a few red cells. Almost 100 per cent of the nucleated cells were viable.

The immunization schedule was irregular. In general, however, the first 4 to 6 inoculations were at weekly intervals, with subsequent booster doses as indicated on the basis of the horse leukoagglutinin titers. The cell doses ranged from 0.2 to 194 billion. The dose-response relationship is discussed later. When the horses were bled, 5 to 10 liters were removed.

Equine immunologic response

Serial leukoagglutinin titers against the white cells of dog or human buffy coat were measured in the immunized horse serum by a modification of the methods of Payne and Dausset. Serial twofold dilutions of test serum were made in buffered saline. The titer was expressed as the reciprocal of this dilution. To each dilution, an equal volume, 0.1 milliliter of leukocyte suspension was added and incubated at 37 degrees C. for 1 hour. Spot checks of lymphocytoagglutinins in the same serums were made using dog and human thoracic duct lymphocytes for test cells. Hemagglutinins against dog and human red cells were also determined using a 1.5 per cent red cell suspension in saline added to an equal volume of serum. Readings were taken after incubation for 30 minutes at 37 degrees C.

Antilymphoid substances studied

Antidog-lymphoid plasma with titers of 1:16 to 1:256 was first used. The horses were bled into heparinized bottles. The plasma was separated by centrifugation, heated at 56 degrees C. for 30 minutes, passed through Seitz filters, pooled with the plasma of several other horses, and given to dogs by intraperitoneal injection.

Next, pooled antidog-lymphoid serum was prepared from the coagulated blood of 4 of these same horses. This serum was heated as described and absorbed for 15 minutes at 37 degrees C. against 10 per cent pooled dog red cell pack. It was then used for intraperitoneal injections. The titer was 1:32 to 1:128.

When high titer antidog-lymphoid serum was eventually obtained, more extensive absorption procedures were tried, first by mixing 1 volume of pooled normal dog serum, which had been heated at 56 degrees C. for 30 minutes, to 10 parts of immune horse serum. The mixture was incubated for 12 hours at 4 degrees C., centrifuged at 6,000 revolutions per minute for 30 minutes and the sediment discarded. The residual serum was then absorbed 4 times with 30, 30, 20, and 10 per cent washed dog red cell pack for 1 to 2 hours at 4 degrees C. In addition, some serums were absorbed against 10 to 25 per cent dog kidney cell pack, and against 20 to 30 per cent liver cell pack. Details of preparation of cell pack from the solid organs is described elsewhere (11). The volume of supernatant after each absorption was approximately the same as the original serum volume.

The antihuman-lymphoid serum was treated in the same way. Blood from 10 to 20 human donors of all blood types was separated into red cells and serum. The serum was pooled as were the red cells after washing 3 times with saline. Details of absorption were as described in the foregoing. When kidney and liver tissues were used for absorption, these were obtained from fresh cadavers and perfused free of blood with chilled lactated Ringer's solution before preparation of the parenchymal cell pack. For reasons discussed subsequently, most of the antihuman serum was absorbed only with red cells and serum.

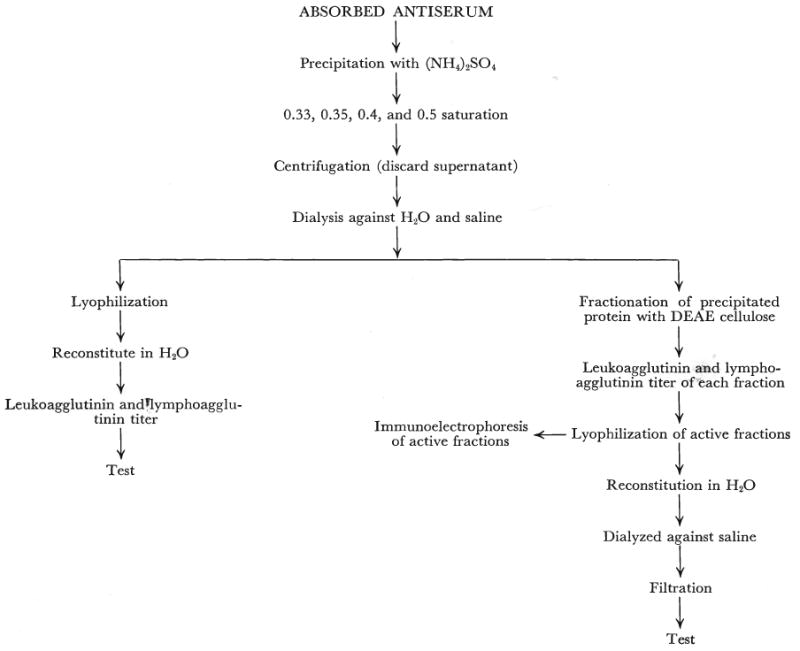

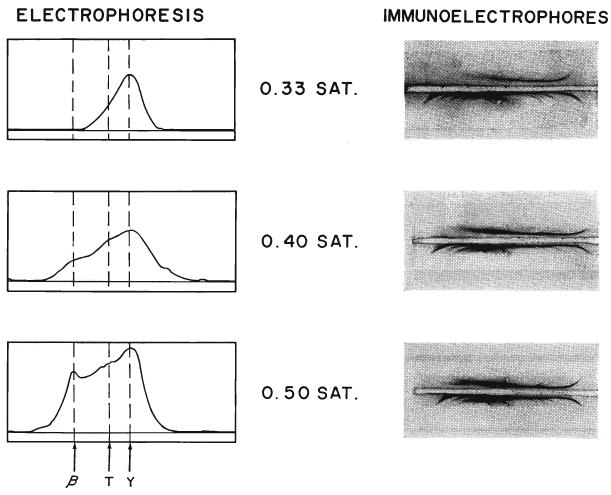

Several fractions were prepared from the absorbed antihuman and antidog-lymphoid serum (Fig. 1), using standard biochemical methods. For each, the starting point was precipitation with ammonium sulfate at 0.33, 0.35, 0.4, or 0.5 saturation. In a few instances precipitation was performed at 0.35 saturation and a reharvest of the supernatant at 0.5 saturation was later obtained, but in most only a single precipitation was employed.

Fig. 1.

The methods used for preparation of crude horse globulin from absorbed serum and for determination of the antibody-containing portions of the globulin.

Many of the protein precipitates obtained with ammonium sulfate were concentrated by lyophilization and stored. The precipitate was dialyzed at room temperature against tap water for 24 hours and then at 4 degrees C. for 12 hours against saline. The crude globulin was then lyophilized, stored in vacuum bottles, and placed in a desiccator. For use, the powder was reconstituted with 1 volume of distilled water for every 4 volumes of the original horse serum. The sodium chloride content of the powder plus the distilled water made up a final solution of approximately physiologic saline. It was sterilized by passage through a Seitz filter and stored at −20 degrees C. The titer of the antidog globulin was 1:512 to 1:1024. The antihuman material had a titer of 1:4096 to 1:16,384.

Fractionation of both the raw serum and the ammonium sulfate precipitate was performed with diethylaminoethanol cellulose anion exchangers by the method of Sober and Peterson. Eluates from the diethylaminoethanol cellulose columns were subjected to electrophoresis by the Beckman microzone electrophoresis system using phosphate buffer of ph 8.0, 0.075 M. Immunoelectrophoresis was by the method of Scheidegger. For the latter examinations a barbiturate buffer of 0.1 M and ph 8.6 was used. The current was 100 volts, 5 milliamperes, applied for 60 minutes.

Studies after administration

Mortality and the incidence of toxic reactions were determined for each antilymphoid substance. The effects upon renal and hepatic function and upon formed blood elements were monitored in both the dogs and patients.

Precipitin titers against normal horse serum were determined as a measure of the canine or human response to the immune horse globulin, employing a twofold dilution test which was read with the naked eye. Dog or human serum was added to an equal volume of normal horse serum, incubated for 30 minutes at 37 degrees C. and 30 minutes at room temperature. In addition, intradermal skin test reactions to 0.1 milliliter of the protein product used clinically were measured before and at intervals after the institution of therapy. Readings were taken after 30 minutes and 24 hours. Finally, the patient serums were assayed for hemagglutinin titers against sheep red blood cells to determine if Forssman-like antibodies developed, using the double dilution method described earlier to study horse hemagglutinins.

Pathologic studies

The dogs which had received antilymphoid products were autopsied and all the tissues studied by light microscopy. A number of animals had biopsies which permitted electronmicroscopic analysis of the kidneys, lymph nodes, spleen, or liver, as well as examination of frozen tissues.

The tissues were classified according to the type and route of therapy used:

Six dogs without transplants which received 1 to 4 milliliters per kilogram per day unabsorbed immune plasma intraperitoneally until their death after 8 to 13 days.

Ten dogs without transplants which received 2 to 6 milliliters per kilogram per day partially absorbed immune serum intravenously for 6 to 70 days. The 2 animals treated for 70 days had biopsies, followed by cessation of therapy for 15 days at which time they were rebiopsied and sacrificed.

Two dogs without transplants which received 1 to 4 milliliters per kilogram per day of the same serum described in group 2 but by the intraperitoneal route. One was treated for 33 days and died. The other had 45 days of injections. Therapy was then stopped for 28 days after which time biopsies were obtained.

Two dogs whose kidneys, spleen, and lymph nodes were studied 74 and 76 days after orthotopic liver transplantation. These animals had received 51 and 30 days of intraperitoneal treatment respectively with the same serum described in group 2. Therapy had been stopped for 51 and 75 days before the biopsies. No other immunosuppressive therapy was given.

Two dogs without transplants which received 17 days of subcutaneous therapy with immune serum which had been absorbed completely with red cells as well as with kidney and liver. They died of subcutaneous sepsis.

Six dogs which received 0.3 to 0.4 milliliter per kilogram per day immune globulin subcutaneously for 31 to 56 days. The injectate had a protein content of 8 grams per cent.

Three dogs whose kidneys, spleen, and lymph nodes were studied after 60 days of therapy with 0.2 milliliter per kilogram per day of immune globulin which had been started on the day of orthotopic liver transplantation. The injectate had a protein content of 4.6 grams per cent. No other immunosuppression was used.

Four control dogs given subcutaneous injections for 30 days with lyophilized globulin prepared from normal nonimmunized horses. They received 0.63 milliliter per kilogram per day of an injectate containing 4.5 grams per cent protein.

In addition, the spleens were examined from 7 uremic patients who had received antihuman-lymphoid globulin for 5 to 35 days. The specimens were removed at the time of renal homotransplantation. Lymph nodes were available from 3 of these patients. The reconstituted globulin which had a leukoagglutination titer of 1:8192 to 1:16,384 was given intramuscularly in a dose of 4 milliliters per kilogram per day. Protein content was 8.7 grams per cent.

Results

Influence of immunization variables

Early in the study when lymph nodes were used as the antigen source, the total weekly cell dose from dog donors ranged from 0.5 to 19 billion. The horse immunized with human lymph node or thymus cells had irregularly spaced individual doses of 0.18 to 1.4 billion. Within a few weeks, the antidog and antihuman leukoagglutinin titers increased from control values of 0 to 1:4 to as high as 1:256 and 1:32 respectively. These titers did not rise further despite similar repeated booster doses over periods of as long as 6 months.

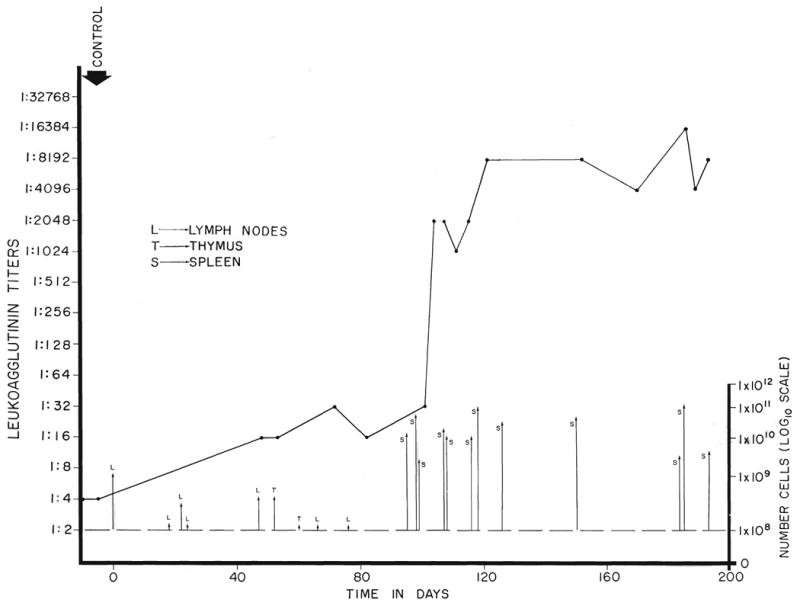

Later, the antigen dose was radically increased by employing 4.1 to 194 billion spleen cells. The titers responded within a few days or weeks to levels of as high as 1:16,384. An example in a horse immunized against human cells is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Effect of immunizing dose upon the leukoagglutinin titer of a horse inoculated with cadaveric human lymphoid tissue. Note that the rise in titer was very modest during the first 3 months, during which time small doses of cells were used. When the quantity of antigen was increased by the use of spleen cells, abrupt increases in titer were observed within a few days.

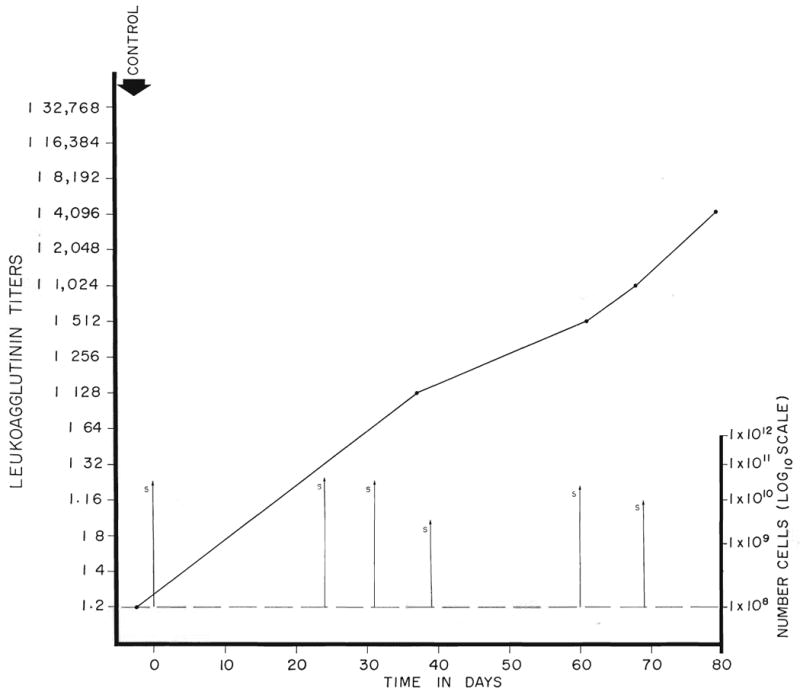

Subsequently, 4 additional horses were immunized with only canine spleen in weekly doses of 52 to 214 billion cells from the start, and a fifth animal was prepared with doses of 5.1 to 32 billion human spleen cells (Fig. 3). All 5 horses responded with leukoagglutinin titers of 1:2048 to 1:16,384 within 20 to 75 days. With sufficiently large numbers of cells, a horse can thus be effectively immunized relatively quickly.

Fig. 3.

The leukoagglutinin response in a horse immunized solely with human spleen cells. The individual cell doses were 5 to 30 billion. Note the progressive increase in titer to 1:4,096 after 80 days.

Features of the equine immunologic response

The leukoagglutinin titers of both the antidog and the antihuman-lymphoid serums were approximately the same as the lympho-agglutinin titers determined by testing against thoracic duct lymphocytes of the respective species.

Some variability of the effect of the crude globulin was evident inasmuch as the white cells from different donors were not all agglutinated to the same dilution. Thus 1 batch, which agglutinated at 1:4096 for 6 of a panel of 10 donor white cells, had a titer of 1:2048 to 1:16,384 for the others. Furthermore, interspecies reactions were also noted. Antidog-lymphoid globulin of high titer also weakly agglutinated human white cells. A similar interspecies reaction was found with antihuman-lymphoid globulin. These interesting observations have been reported in detail by Putnam and his associates.

The most easily studied undesirable antibodies were the hemagglutinins. The natural heterohemagglutinin titer against either dog or human red cells was 1:2 to 1:8. After immunization, the hemagglutinin titer rose to as high as 1:100,000. The hemagglutinin titer usually exceeded that of the leukoagglutinins.

Effect of absorption on antibody titers

Absorption with red cell pack removed essentially all hemagglutinins without affecting the leukoagglutinin titers. Absorption with pooled dog or human serum to remove antibodies against serum protein also did not reduce the leukoagglutinin titers. However, a single exposure to kidney and liver cells caused the loss of 75 per cent or more of the antiwhite cell titer in both the antidog and the antihuman horse serum (Table I). With longer absorption periods or greater concentrations of liver and kidney cell pack, the loss of leukoagglutinin titer was even greater. When absorption with 50 per cent volume of either kidney or liver was carried out 4 times, the titer loss was approximately 90 per cent.

TABLE I. Effect of Absorption Procedures Upon Antibody Titers in the Serum From a Horse Immunized Against Human Lymph Node, Thymus, and Spleen Cells.

| Volume, ml. | Leukoagglutinin | Hemagglutinin | Antihuman protein precipitins | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original antilymphoid serum | 2250 | 1:4096 | 1:16,384 | 1:64 |

| After serum absorption (1 X) | 2370 | 1:4096 | 1:16,384 | 0 |

| After red cell absorption (4 X) | 2300 | 1:4096 | 1:2 | 0 |

| After kidney (1 X) and liver (1 X) absorption | 2400 | 1:1024 | 1:2 | 0 |

Effect of ammonium sulfate precipitation and lyophilization upon leukoagglutinin titers

A pooled collection of antidog horse serum was divided into 3 aliquots of 60 milliliters and each precipitated 4 times at either 0.33, 0.4, or 0.5 saturation ammonium sulfate. The precipitate was dialyzed, reconstituted with water to the original serum volume, and again tested. The original titer of the serum was 1:2048 and contained total protein of 7.8 grams per cent. With precipitation at 0.33 saturation only 0.6 gram per cent protein was recovered, and the reconstituted product had a titer of 1:64; the titer loss was therefore 94 per cent. In contrast, 2.9 and 3.5 grams per cent of protein were retrieved at 0.4 and 0.5 saturation respectively. In both, the titer of the reconstituted material was 1:1024.

A similar harmful effect of precipitation at too low a concentration of ammonium sulfate was demonstrable when this process was carried out only once rather than 4 times. Under these circumstances the agglutinin loss was usually negligible with precipitation at either 0.4 or 0.5 saturation, but with 0.35 saturated solution 50 per cent or more of the antibody was lost. The effect of lyophilization on the leukoagglutinin titers was variable, but in some instances was significant. The various protein precipitates were further characterized as described subsequently.

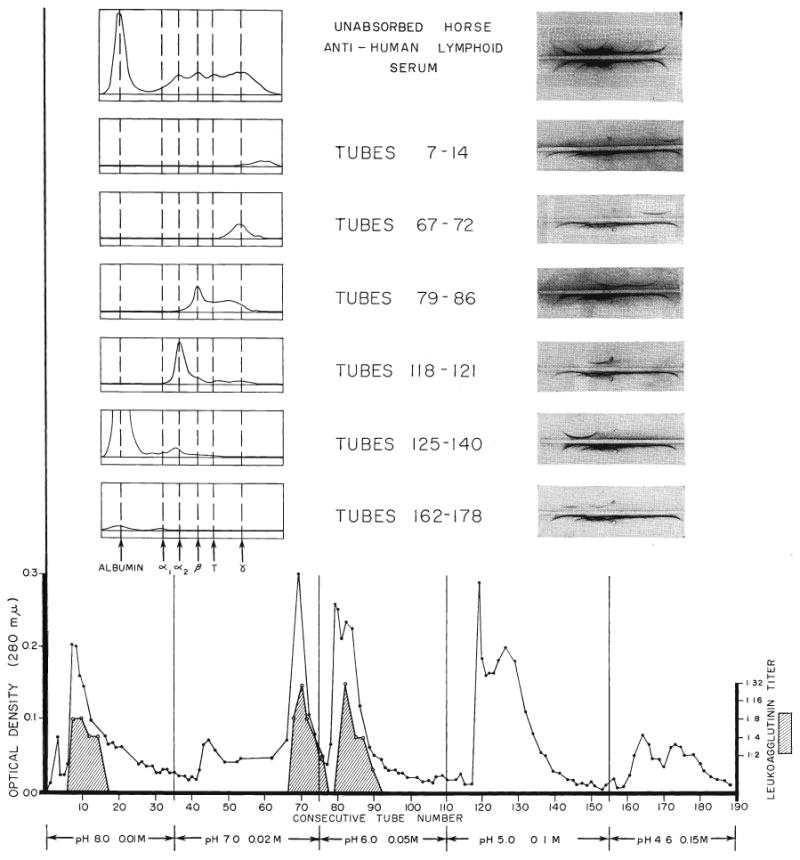

The nature of the antilymphoid antibody

Two milliliters of antihuman-lymphoid serum were applied to a 10 gram diethylaminoethanol cellulose column and fractionated into 190 tubes, each containing 10 milliliters. Elution was with phosphate buffers of ph 8 and 0.01 M, ph 7 and 0.02 M, ph 6 and 0.05 M, ph 5 and 0.1 M, and ph 4.6 and 0.15 M. The material in each collecting tube was tested for its ability to agglutinate white cell pack or pure thoracic duct lymphocytes. The results are shown in Figure 4. The leukoagglutinins were positive in the fractions eluted with ph 8. They were present in even higher titer in the elutions at ph 7 and ph 6. By calculation of the curve areas, the eluates at ph 8, 7, and 6 contained approximately 30, 35, and 35 per cent of the antibody respectively.

Fig. 4.

Studies of the leukoagglutinin-containing fractions in antihuman-lymphoid serum with the use of column chromatography, electrophoresis, and immunoelectrophoresis. The various eluates from the diethylaminoethanol cellulose column were analyzed spectrophotometrically for protein content, expressed as optical density, and the presence or absence of leukoagglutinins determined for each collection tube. The electrophoresis and Immunoelectrophoresis permitted relatively complete classification of the active immunoglobulins.

The proteins in the individual tubes were concentrated to one-tenth the collected volume by dialysis against carbowax and then analyzed electrophoretically and immunoelectrophoretically to characterize the active protein. These studies (Fig. 4) showed that the leukoagglutinating elutions from ph 8 and ph 7 were gamma globulin. Those tubes with agglutinating antibodies from the ph 6 eluate had an electrophoretic mobility characteristic of a mixture of beta globulins, T equine fraction, and gamma globulins, a conclusion supported by the results of immunoelectrophoresis. The inactive tubes in the ph 5 and ph 4.6 elutions contained alpha globulins and albumin.

Exactly the same procedures were carried out on antidog serum which had been absorbed with dog red cells, serum, kidney, and liver. The residual leukoagglutinating antibody appeared in the same 3 eluates.

Finally, the same analysis was applied to precipitates obtained from unabsorbed antidog serum with 0.33, 0.4, and 0.5 saturation ammonium sulfate. After precipitation 4 times with 0.33 saturation, and diethylaminoethanol cellulose chromatographic separation, the eluate at ph 8 had a moderately reduced quantity of protein which was shown to be pure gamma G globulin by electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis. The other eluates including those antibody fractions at ph 7 and ph 6 contained only a trace of protein.

In contrast, the precipitates obtained with 0.4 and 0.5 saturation ammonium sulfate had eluates at ph 8, 7, and 6 which resembled those of raw serum and which also had electrophoretic and immunoelectrophoretic properties of gamma and beta globulins and the equine T fraction. Only traces of additional protein were found in the other eluates from the material precipitated at 0.4 saturation. At 0.5 saturation, however, significant quantities of alpha2 macroglobulins and traces of albumin were contaminants.

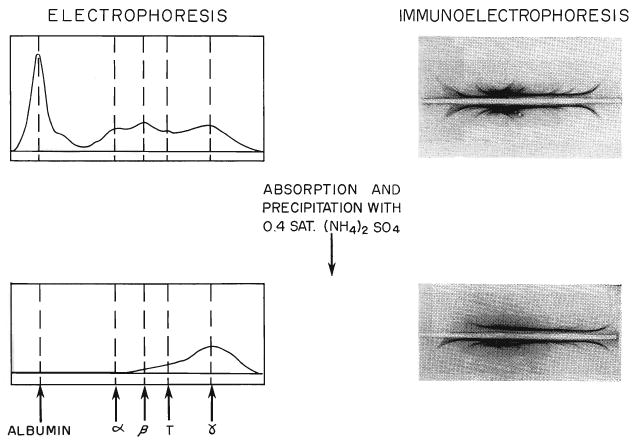

Selection of an antilymphoid product for clinical use

These results explain the critical effect of ammonium sulfate concentration upon the potency of the final product as described earlier. With too low a saturation, pure gamma G globulin (Fig. 5, top) is obtained but with a reduced quantity of the desired antibody. With too high a saturation, the penalty for retention of the antibody is the necessity to accept contamination with extraneous horse protein (Fig. 5, bottom). Therefore, the technique finally adopted for clinical use was double precipitation with 0.4 saturation, a method which usually permits retention of approximately 50 per cent of the leukoagglutinating antibodies with a minimum of unwanted components.

Fig. 5.

Electrophoresis and Immunoelectrophoresis of the horse protein obtained by precipitating 4 times at different saturations of ammonium sulfate. Note the progressively heterogeneous nature of the precipitate with higher ammonium sulfate concentrations. The globulin obtained with 0.4 saturation was used clinically.

The features of a batch of antihuman-lymphoid globulin prepared by this method are illustrated in Figure 6. The volume of serum processed was 2,400 milliliters. After absorption with red cell pack and serum, it had a titer of 1:8,192. Following 2 precipitations with 0.4 saturation ammonium sulfate, 2 washings, and lyophilization, the final product, which was reconstituted to 810 milliliters, had a titer of 1:8,192. Although the antibody loss during preparation was thus approximately 67 per cent, the final product was still sufficiently potent for use in small volumes. Of the 205 grams protein in the raw serum, 56.7 grams or 22 per cent had been retained. The refined material consisted almost entirely of gamma globulin with a trace of beta globulin.

Fig. 6.

Electrophoresis and Immunoelectrophoresis of absorbed antihuman-lymphoid serum and the protein obtained from it by 2 precipitations with 0.4 saturated ammonium sulfate, 2 dialyses, and lyophilization. The final product, which was used clinically, consists almost entirely of gamma G globulin.

In our hands, the most practical means to date for globulin preparation has been with the ammonium sulfate method. However, the results with column chromatography prompted efforts to separate therapeutic quantities of the leukoagglutinating antibody with diethylaminoethanol cellulose columns. Raw serum or crude globulin obtained from a single precipitation with 0.4 saturation ammonium sulfate was used for substrate. In all our early efforts using various ph and phosphate buffer strengths, the loss of leukoagglutinin titer in the resultant purified protein was 90 per cent or more. More recently, using a single column separation at ph 6 and a phosphate buffer of 0.05 M, 60 per cent of the antibody was retained. The facility with which this method can be applied commercially may make it the preferred technique for production in the future.

Mortality from serum

Thirty-six dogs without transplants were given 1 to 4 milliliters per kilogram per day unabsorbed antilymphoid plasma which had a leukoagglutinin titer of 1:16 to 1:256. Eleven of the animals died within 15 days. The greatest risk was with the first few injections. Often, generalized convulsions developed. In others, acute anemia contributed to the morbidity.

The antilymphoid serum which had been partially absorbed with dog red cells was also given intraperitoneally in the same dose to 19 dogs for 16 to 22 days. There were no deaths during this period. This serum given intravenously in doses of 2 to 6 milliliters per kilogram per day to 10 other dogs caused the death of 4 animals. Four others received renal or hepatic homotransplantation after 10, 11, 21, and 23 days; these animals, which were ill, all died promptly. The other 2 dogs continued to receive serum intravenously for 70 days.

Crude globulin prepared from the serum of immunized horses was given subcutaneously to 29 dogs without transplants for 8 to 60 days in doses of 0.2 to 0.5 milliliter per kilogram per day. Leukoagglutinin titers were 1:512 to 1:1,024. Two animals died of subcutaneous coliform infection. There was no other mortality. Although the crude globulin used was variable, having been precipitated with 0.35, 0.4, or 0.5 saturation ammonium sulfate, no difference in toxicity of the different products was evident. Furthermore, there was no apparent difference in safety if absorption of the original serum had been accomplished with canine red cells, serum, kidney, and liver as compared to that if absorption had been only with red cells and serum.

There was no mortality from globulin used clinically on patients.

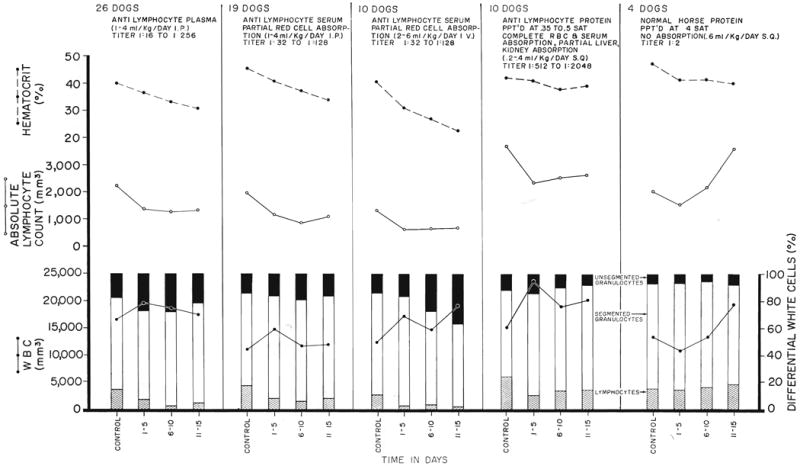

The influence of antilymphoid products upon the peripheral blood

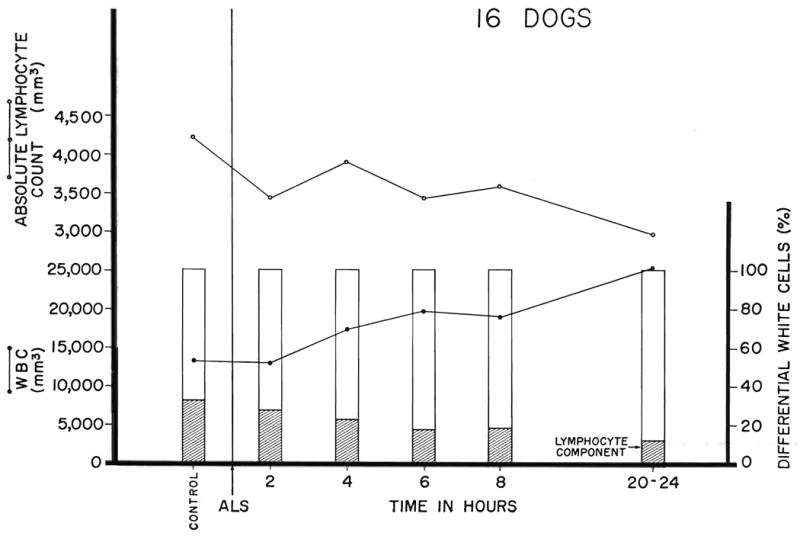

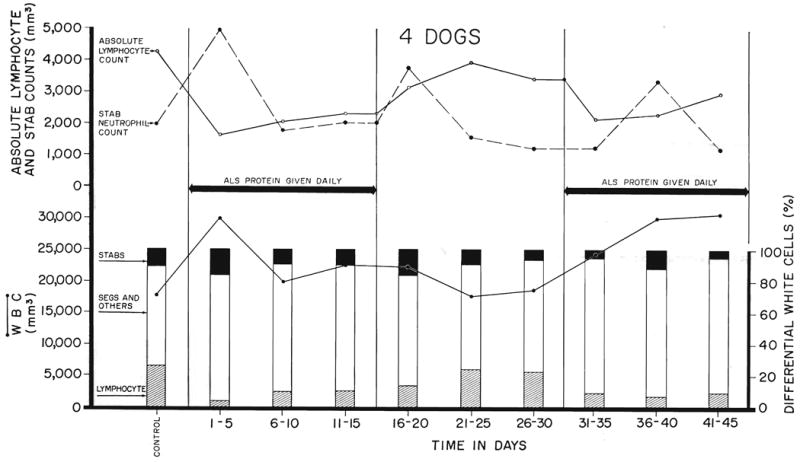

The canine response to antilymphoid plasma or serum and various globulin derivatives is summarized in Figure 7, along with results obtained from 4 control animals which received globulin prepared from the serum of a nonimmunized horse. Lymphopenia was produced with each of the antilymphoid preparations but not with the nonspecific horse serum. The most easily demonstrable effect was upon the lymphocyte differential count. The diminution in the absolute lymphocyte counts was less striking because of the increase in the total white cell count which almost invariably occurred. There was very often an increase in immature granulocyte forms. All of these changes tended to occur quickly. After an injection, the reduction in lymphocytes was first detectable within 2 to 6 hours (Fig. 8), with a maximum effect in 8 to 24 hours. With the discontinuance of therapy (Fig. 9), the return of peripheral lymphocytes was usually complete within 5 to 10 days.

Fig. 7.

The effect of horse plasma or serum and crude horse globulin upon the hematocrit, lymphocyte count, total white count, and white count differential during 15 days of daily administration. In all but the control experiments on the right, the agents were prepared from horses immunized against dog lymphoid tissue. Note that acute anemia was largely prevented only when complete absorption had been carried out with canine red cell pack.

Fig. 8.

The acute response in dogs of the lymphocyte differential, absolute lymphocyte count, and total white count to subcutaneous crude horse globulin prepared from the serum of immunized horses. The dose of globulin was 0.2 to 0.4 milliliter per kilogram per day with a leukoagglutinin titer of 1:512 to 1:1, 024. Note that the lymphopenic effect is clearly demon strable in 4 to 6 hours and that it lasts for at least 1 day.

Fig. 9.

The effect in dogs of 2 separate courses of globulin prepared from the serum of immunized horses. Note the rapid recovery from the lymphopenia when the drug was discontinued after 15 days of therapy, and the recurrent lymphopenic response to a second course of injections started 16 days later. “Stabs” refer to nonsegmented neutrophiles.

Although the lymphopenic effect was thus comparable with both the unpurified and purified antilymphoid substances, there was an important difference in the effect upon the hematocrit. In the animals which received intraperitoneal injections of either unabsorbed antilymphoid plasma or antilymphoid serum which had been subjected to partial red cell absorption, acute anemia developed. This undesirable effect was even more pronounced when antilymphoid serum was given intravenously (Fig. 7). This complication was not present in most of the globulin products derived from horse serum which had been completely absorbed with dog red cells. However, isolated batches of the latter material also caused anemia despite the proved absence of hemagglutinins.

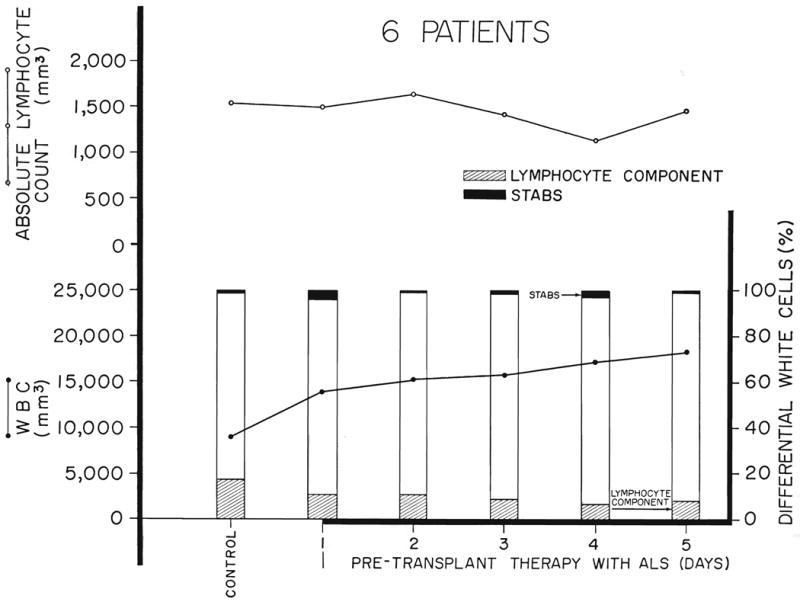

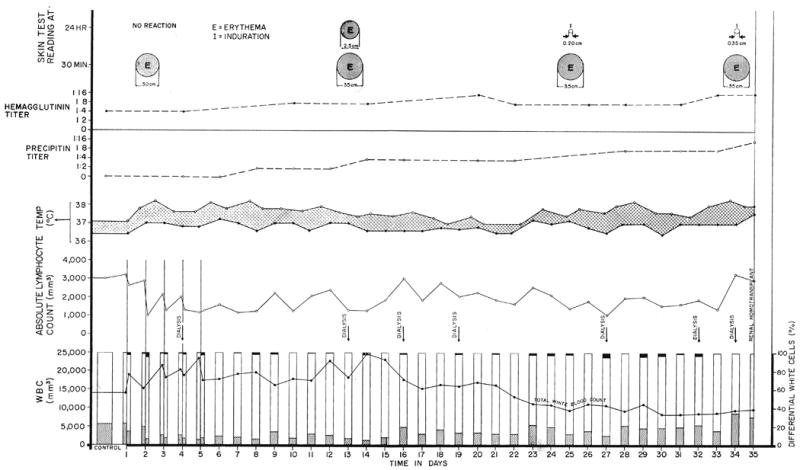

Six patients had similar studies during the daily intramuscular administration of immune horse globulin for 5 days prior to renal homotransplantation. The material which had a leukoagglutinin titer of 1:8,192 to 1:16,384 was given in 4 milliliter doses. The results were similar to those in dogs in that the lymphocyte differential count was immediately decreased in all (Fig. 10). However, total increases in white count also invariably occurred with the result that the absolute fall in lymphocyte count was not statistically significant. The course of a seventh patient who was awaiting a cadaveric kidney is shown during a 35 day period (Fig. 11). In the last patient, the initial reduction in the lymphocyte differential was not well sustained after 2 weeks. The anemia which was present in these uremic patients prior to therapy did not seem to be made worse.

Fig. 10.

The effect of antihuman-lymphoid globulin in 6 patients treated daily for 5 days before renal homotransplantation. “Stabs” refer to nonsegmented neutrophiles.

Fig. 11.

The course of a patient who received 4 milliliters daily of antihuman-lymphoid globulin for 35 days while awaiting a cadaveric transplant. Note the early sharp drop in the lymphocyte differential. However, because of an increase in total white count, the number of circulating lymphocytes was altered only slightly. The low grade fever recorded was apparently due to the horse protein. However, the serially performed intradermal skin tests did not change markedly, and only minor increases occurred in precipitin and hemagglutinin titers. The temperature curve depicts the highest and lowest recording for each day.

Evidence of toxicity in patients

An annoying side effect of the antilymphoid globulin in the patients was intense pain at the site of the intramuscular injection, particularly for the first few days. The patients usually did not complain at the time of injection but from 2 to 4 hours later a sensation of a muscle cramp was described. Several found that the symptoms could be alleviated by exercise, and in all the pain diminished with subsequent injections. In 1 patient narcotics were initially necessary. By the following morning the patients were usually symptom-free. These cyclic events were accompanied by variable degrees of swelling and edema around the injection sites. In all of the patients fever developed, as shown in one patient in Figure 11.

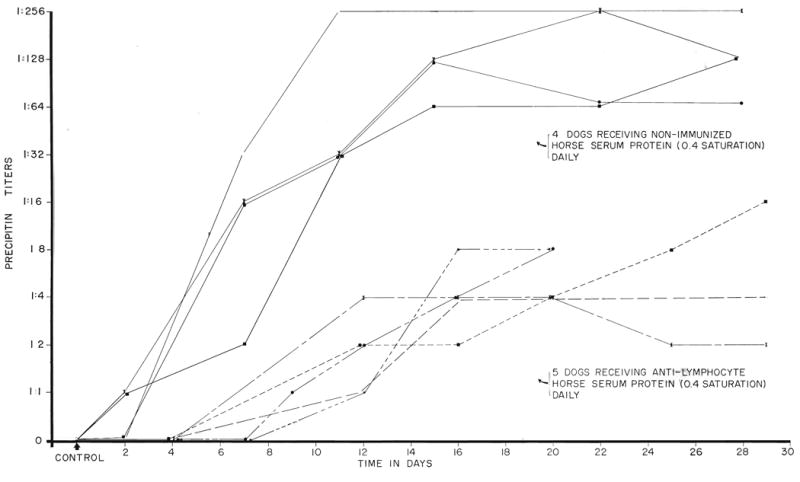

Immunologic measurements in the host

In 4 dogs which were given crude globulin obtained from the serum of normal horses high precipitin titers developed against normal horse serum within 11 days (Fig. 12). In contrast, dogs receiving globulin derived from the serum of horses immunized with dog lymphoid tissue had precipitin titer rises no greater than 1:16 during the first 30 days (Fig. 12). Four other dogs had similar treatment with immune globulin for 15 to 17 days. With discontinuance of injections for 17 days, the precipitin titers, which had increased to a maximum of 1:8, returned to 0 or 1:2. After resumption of therapy, the precipitin titers rose again but did not exceed 1:8 during the next 25 days of continuous injections. Spot checks in 4 other dogs which had received immune horse globulin therapy from 20 to 100 days previously all had antihorse-protein precipitin titers of less than 1:4. These data suggest that the risk of delayed serum sickness after cessation of therapy is not excessive, and that a prior course does not necessarily preclude later repeat treatment.

Fig. 12.

The response of canine precipitin titers to horse protein during daily injection of globulin prepared from the serum of nonimmunized and immunized horses. Note the striking difference in the 2 groups of dogs.

Antihorse precipitin titers were also determined during 2 to 3 months of serum therapy for 7 patients who had received transplants. Before operation these patients received only antilymphoid globulin, but afterward they also were treated with azathioprine, and in some instances prednisone. The precipitin titers increased from control values in 6 instances to 1:4 or 1:8 and in the other to 1:32 (Fig. 11).

The hemagglutinin titers against sheep red cells were studied in the 7 patients during the same intervals. In 2 patients these rose from 1:2 to 1:256 or 1:512. In 2 others, the titer rose to 1:32, and in the other 3 there was no increase. The patients were also studied with serial skin tests (Fig. 11). The skin reaction after 2 to 3 months showed no change in 1, a slight increase in 4, a moderate increase in 1, and a decrease in the other.

Effect on renal and hepatic function

Biochemical evidence of injury to either the kidney or liver was detectable only when the partly absorbed antilymphoid serum was given intravenously in doses of 4 to 6 milliliters per kilogram per day. Two of these dogs became uremic. Four of the animals had rises in serum glutamic oxalacetic transaminase or serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase, and 2 of the 4 became clinically jaundiced. There was no evidence of renal or hepatic injury with the same doses of this material given intraperitoneally for at least 15 days.

The same studies were also determined in 29 dogs which were subcutaneously administered the globulin derivatives prepared from immune horse serum. Abnormalities did not develop in a single one of these dogs during the period of study.

The 7 patients who received immune horse globulin had end-stage renal disease. A complete battery of liver chemistry tests repeated serially after the beginning of treatment was unchanged in each instance.

Canine pathologic studies

Lymphoid hyperplasia was present in many of the dogs treated with immune plasma, serum, or globulin, particularly in animals treated for 2 months or longer. In the spleens, the follicles were bigger and more numerous than in untreated dogs (Fig. 13). The follicular centers were crowded with large and medium-sized cells with lightly pyroninophilic cytoplasm and large, pale nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Many of these cells were in mitosis (Fig. 14). Ultrastructurally these pyroninophilic blast cells were characterized by the very numerous free ribosomes that filled their cytoplasm. The cells had only a very few flattened cisternal profiles of rough endoplasmic reticulum and moderate numbers of mitochondria. The Golgi apparatus was usually well developed (Fig. 15). Reticular cells and macrophages were present and some contained ingested nuclear debris. The mantle and marginal layers of the follicles were greatly reduced in thickness and contained very few small lymphocytes. In the periarteriolar sheaths of the red pulp there were many aggregates of lymphoid cells which were smaller and possessed more deeply pyroninophilic cytoplasm than the cells in the follicles; there were also some plasma cells.

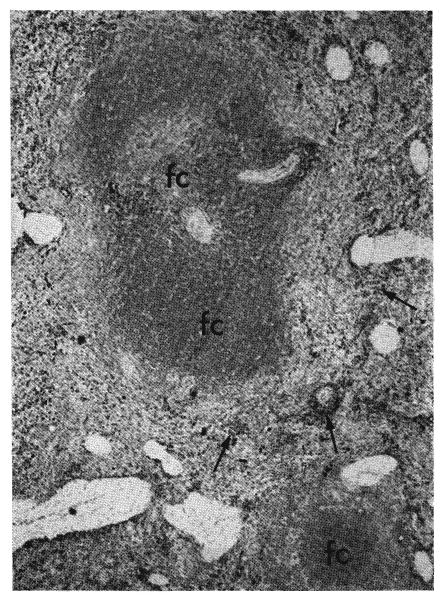

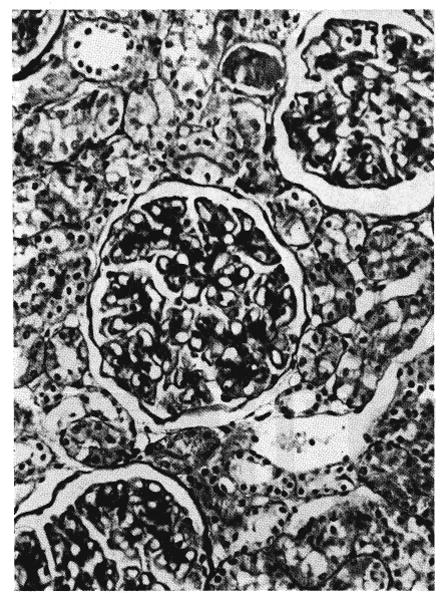

Fig. 13.

Two large follicles in the spleen of a dog which had been treated for 56 days with absorbed immune globulin given subcutaneously. The follicular centers (fc) appear dark gray because they are occupied by cells which have only a little pyronin-positive cytoplasm. In the red pulp groups of cells, which appear black because they have a greater amount of deep red cytoplasm, are clustered along the arterioles and small arteries (arrows). Methyl green pyronin, ×20.

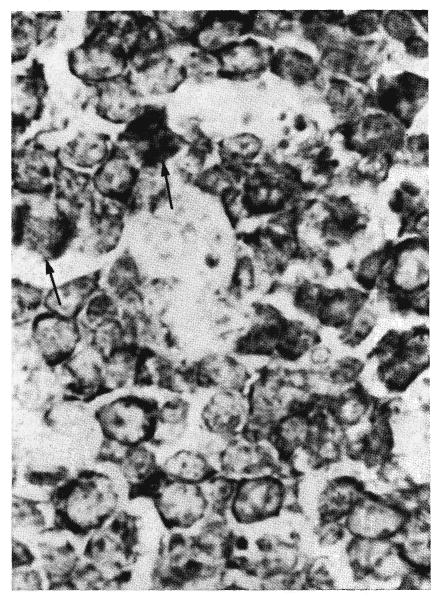

Fig. 14.

Higher magnification of one of the follicular centers shown in Figure 13. It is composed of large and medium-sized cells each with a thin rim of red cytoplasm which appears black in this photograph. The nuclei are large. The unstained areas are the cytoplasm of macrophages. Two cells are in mitosis (arrows). Methyl green pyronin, ×250.

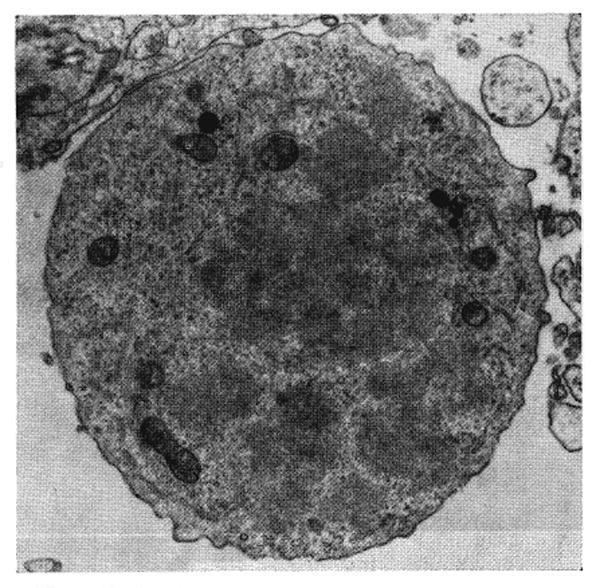

Fig. 15.

Dividing large blast cell from splenic white pulp shown in Figures 13 and 14. The cytoplasm is filled with ribosomes grouped in clusters. There are a few solitary profiles of endoplasmic reticulum. Lead hydroxide, × 5,064.

In the majority of these treated animals the lymph nodes throughout the body were either normal in size or enlarged. The cortex contained numerous germinal centers composed of proliferating, large pyroninophilic cells similar in gross and fine structure to those encountered in the splenic follicles (Fig. 16). The number of small lymphocytes surrounding these centers was greatly reduced. The medulla contained varying numbers of smaller, deeply pyroninophilic cells and some plasma cells.

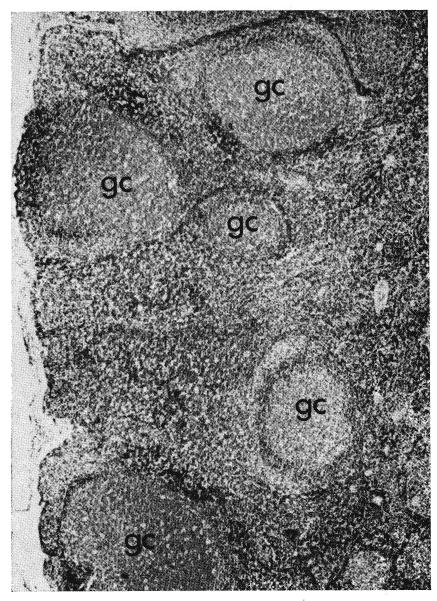

Fig. 16.

Many large germinal renters (gc) in a lymph node from a dog which had been treated intravenously with antilymphoid serum for 70 days. Hematoxylin and eosin, ×20.

The thymuses were normal for the age of the animals. There were no germinal centers.

The kidneys were examined from 21 dogs treated with immune plasma, serum, or globulin and compared with the kidneys from 4 control dogs similarly treated with subcutaneously injected globulin obtained from nonimmunized horses. Two of the 4 control animals had many dense deposits on the epithelial side of the glomerular capillary basement membranes. In some glomeruli there were also deposits in the lamina densa, on the subendothelial aspect of the capillary basement membrane and in the mesangial matrix. These changes were associated with focal fusion of the epithelial foot processes and a variable amount of endothelial cell hyperplasia. The fluorescent antibody technique revealed horse gamma globulin, dog immunoglobulin G, and beta1C complement as small beads in the glomerular capillary loops of the 2 dogs with ultrastructural deposits. By ordinary light microscopy, however, periodic acid-Schiff positive thickening of the glomerular capillary basement membranes could only be detected in 1 of the dogs.

Ten of the 31 dogs treated with antilymphoid agents had periodic acid-Schiff positive thickening of the glomerular capillary basement membrane, evident with light microscopy (Fig. 17). Another 3 showed glomerular deposits only with the electron microscope. In the animals treated for the longest periods, these changes were occasionally accompanied by hypercellularity of the tufts and adhesions between tufts and capsules. Ultrastructurally, the same dense deposits were present on the subepithelial aspects of the glomerular capillary basement membranes and in the mesangium of these animals as were seen in the control group treated by normal horse globulin (Figs. 18 and 19). The altered basement membranes stained positively for horse gamma globulin, dog immunoglobulin G, and beta1C complement when treated with the appropriate immunohistochemical reagents. Length of treatment was the important factor determining whether renal lesions were present or not: the 13 dogs affected were all among the 21 animals who were treated for 17 days or longer. The route of administration was also important. The highest incidence of lesions was in the group given immune serum intravenously in which in all 6 of the animals treated for more than 17 days glomerular deposits developed. But even in the 11 animals treated subcutaneously for a comparable period, 6 showed glomerular deposits.

Fig. 17.

Microscopic section from the kidney of a dog which had been treated intravenously with partially absorbed antilymphoid serum for 70 days. The glomerular capillary basement membranes and the mesangium are thickened. Periodic acid-Schiff, ×250.

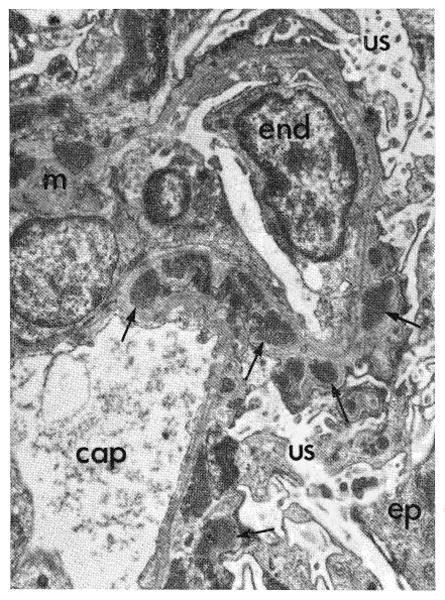

Fig. 18.

Fine structure of glomerulus from kidney shown in Figure 17. Sharply outlined dense deposits (arrows) protrude from the capillary basement membranes toward the urinary space (us). Similar deposits are present in the mesangium (m). Over the deposits some of the epithelial foot processes are fused. An endothelial cell (end) is enlarged. cap, Capillary lumen; ep, epithelial cell. Phosphotungstic acid, × 4,000.

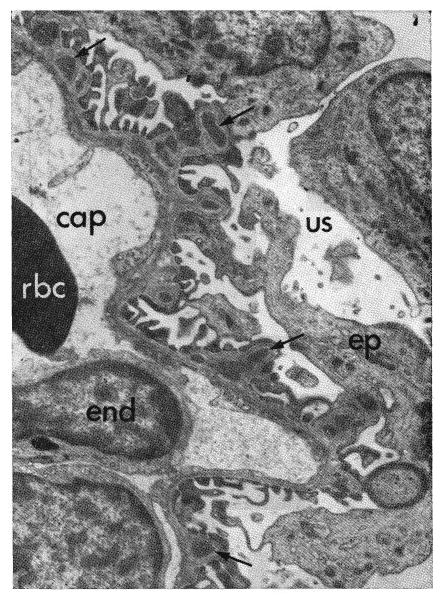

Fig. 19.

Fine structure of glomerulus from dog treated with immune globulin subcutaneously 57 days. The original antiserum had been absorbed against dog kidney, liver, and red cells. Subepithelial dense deposits (arrows), less severe than those in Figure 18, are on the capillary basement membranes. cap, Capillary lumen; end, endothelial cell; rbc, red cell; ep, epithelial cell; us, urinary space. Phosphotungstic acid, ×4,000.

The effectiveness of absorbing immune serum against kidney and liver tissue in reducing the frequency of renal lesions cannot be assessed from these experiments because the route of administration was not constant. Lesion developed in 8 of the 12 animals treated with antilymphoid products absorbed only against red cells as compared with 4 of the 9 animals given completely absorbed materials.

Two of the dogs in which large glomerular deposits developed following 70 days of intravenous antilymphoid serum therapy were re-biopsied after treatment had been discontinued for 15 days. There was no evidence of reversal of the glomerular damage. A third animal which had not been biopsied previously showed small deposits 28 days after cessation of a 45 day course of intraperitoneal antilymphoid serum.

Consistent injury to other organs was not present. A few treated animals had focal myocardial and hepatic necroses, but these were related to terminal infection, not to a direct toxic effect of antilymphoid agents.

Pathologic studies in humans

The amount of lymphoid tissue appeared to be within the range of normal in the 7 spleens arid 3 lymph nodes examined. Germinal centers composed of large, pale pyroninophilic cells were present in 6 of the 7 spleens and in all of the lymph nodes. The number of small lymphocytes surrounding these centers did not seem to be reduced.

Discussion

Interest in the use of antilymphoid serum for the mitigation of homograft rejection dates from the relatively recent reports of Woodruff (28-30), Waksman, Jeejeebhoy, Gray (7) and Monaco (17) and their associates. However, the first experiments with this type of agent were performed by Metchnikoff, who clearly appreciated the potential therapeutic value of such serum products. In 1899, he wrote somewhat philosophically of the struggle between the various cells of an organism and added, “The time is not remote when medical art will actively intervene to maintain the integrity of the whole organism, the harmony of which is broken by the preponderance of certain cells, mononuclear cells in the atrophies, several other elements in the malignant diseases. Therefore I undertook the study of the effect produced by the resorption of macrophages. To attain this end I initially injected guinea pigs subcutaneously with an emulsion of rat spleen or lymph nodes ground up in saline solution. Forty-seven days after this injection, guinea pig serum agglutinated and dissolved rat leukocytes. Mononuclear cells were the most sensitive and were converted into transparent vesicles. Later the granulocytes underwent the same changes and finally the mast cells.” Metchnikoff pointed out that nonimmunized serum did not have these properties. In addition, he observed that guinea pig serum immunized against rats did not agglutinate lymphocytes from other species.

The material used by Metchnikoff was unaltered guinea pig antiserum. Subsequently, Pappenheimer showed that absorption by red cells of the lymphoid donor species did not reduce the antileukocyte activity, a finding confirmed by Cruickshank, Sacks, Levey (14) and Gray (8) and their associates. Pappenheimer's studies indicated as well that inactivation of complement by heating at 56 degrees C. for 30 minutes diminished the cytotoxic but not the leukoagglutinating activity. The latter observation was extended by Gray, Monaco, Wood and Russell, who were able to restore full cytotoxicity by the addition of complement. The latter investigators also showed that absorption of the antiserum by serum of the lymphoid donor species did not affect the leukoagglutinin titer. These important details, originally described in various rodent species, appear from the results in the present study to apply largely to horse serum immunized against dog and human lymphoid tissue. In our preparations, the absorption with red cells seemed to be of the utmost importance, since the high titers of hemagglutinins probably contributed to the anemia otherwise invariably seen in the recipients of the immune serum. In antiserums such as some of those described by Monaco, Wood, Gray and Russell (16) and Levey and Medawar (13) in which hemagglutinin titer rises in the serum donor were not excessive, this step was apparently unnecessary.

In contrast, agreement concerning the effect of absorption of the antiserum by nucleated cells of the donor species is less complete. All workers from Pappenheimer to the present time who have performed the necessary experiments agree that the antiserum is largely inactivated if it is exposed to lymphoid tissue of the original donor species, a finding confirmed in the present study. However, experiments involving absorption with tissues such as kidney, liver, lung, and skeletal muscle have yielded divergent results. Sacks, Fillipone, and Hume demonstrated antibody fixation of their serums to liver, kidney, and muscle, but the consequent effect upon antiserum titer was not specified. Levey and Medawar (13) initially noted little loss of potency when antiguinea pig lymphocyte serum was exposed to guinea pig liver, kidney, and lung, but in subsequent studies the same investigators noted a very definite reduction in potency after exposure to scrupulously washed kidney and lung brei. Such information was specifically sought by Gray, Monaco, Wood, and Russell, who, despite the demonstration of antibody binding to liver, kidney, and skeletal muscle by gel diffusion studies, could not document a consequent fall in either leukoagglutinating or cytotoxic antibody titers. The latter studies supported the hope that a highly specific antilymphoid preparation was easily attainable, which would have an action directed solely against lymphocytes.

The findings in the present study are at variance with those of Gray, Monaco, Wood and Russell. Instead, they support the conclusions of Sacks, Fillipone and Hume, and Levey and Medawar (14) that there is considerable cross reactivity between all cells of the species being treated and that if antigens are uniquely represented in the lymphocytes, they are relatively few in number. Levey and Medawar (14) have strengthened this conclusion in a crucial experiment in which serums were raised in rabbits by immunization with mouse epidermal cells or L-cells from tissue culture. Mice treated with the resulting antiserums had definite prolongation of skin homograft survival.

In the present study, the ease with which cross reactivity could be demonstrated between various nucleated cells of the same species may have been at least partially due to the very high leukoagglutinating titers of the materials being studied. These ranged from 1:1,024 to 1:16,384, whereas the titers when stated in earlier investigations never exceeded 1:64. The same difference in experimental design may explain the lack of complete species specificity documented for the first time in the present report. The latter finding suggests the presence of at least a few cross reacting antigens in the dog and human white cells.

The lack of strict immunologic specificity of the antiserums is not necessarily a fatal flaw. Our data suggest that a small residual fraction of antileukocyte activity is retained after repeated absorption by kidney and liver cells, so that, if necessary, attempts could be made toward purification of this antibody. Alternatively, there is reason to believe that the lymphoid system is a highly vulnerable target, against which antibody action will be more effective than against liver, kidney, and other organs despite the fact that the nonlymphoid tissues possess potential binding sites. Using unabsorbed serums, Levey and Medawar (13) were able to show that florescein-tagged antibody was heavily concentrated in the lymphoid elements.

Although the proper choice of absorption techniques is an important first step, the necessity of obtaining purified products from the resulting antiserums is evident. The first steps in this direction were taken by Waksman and his associates, who reported that crude globulin obtained by ammonium sulfate precipitation was nearly as potent as the original antiserum. These findings have been confirmed by Gray, Monaco, Wood, and Russell and Monaco, Wood, Gray and Russell and in the present report. The development of more effective techniques to obtain high titer raw serum has made it possible further to refine the globulin fraction into a clinically usable form. The exact technique by which this is done is of the utmost importance in our experience, inasmuch as it appears likely that the desired antibody is located not only in the gamma G globulin but also in the beta globulin fraction. With improper selection of ammonium sulfate concentration, much or even most of the antibody is not recovered in the precipitate. Separation of globulin by column chromatography is an even more critical procedure. Nevertheless, the studies herein reported suggest that with properly controlled variables, column separation may ultimately prove to be the best method for bulk production.

The response of dogs and man to antilymphoid serum or its derivatives is not dissimilar to that reported in rodents by Chew and Lawrence and many subsequent investigators, except that the resulting lymphopenia is not so profound. The fact that ammonium sulfate-precipitated globulin can be administered with little grossly observable acute toxicity has raised the important possibility of adding this agent to human immunosuppressive regimens. Nevertheless, there are several important questions of long term morbidity which can be fully answered only by further experience. Many of the earlier workers alluded to the fact that their antiserum was well tolerated, but the periods of administration were limited to a few days or weeks. More recently, Monaco, Wood, Gray, and Russell have described a wasting disease in mice heavily treated with rabbit antiserum which killed all their animals within 42 to 56 days. At autopsy there was virtually complete lymphoid depletion, a finding contrary to the histologic observations of lymphoid hyperplasia made by Chew and Lawrence, Cruickshank, and Levey and Medawar (14) but in accord with those of Waksman. In our animals the striking feature was not atrophy but loss of small lymphocytes and their replacement by large numbers of actively dividing large and medium-sized pyroninophilic blast cells similar to those described by Movat and Harris and their associates during antibody formation, by Gowans and McGregor during graft-versus-host reactions, and by Inman and Cooper after stimulation by phytohemagglutinin. These findings are compatible with Levey and Medawar's hypothesis (14) that the immunosuppressive effect of antilymphoid substances is not dependent upon a lymphocidal action but may be by stimulating transformation of lymphocytes in a manner akin to that of phytohemagglutinin.

The variant results cited may be due to differences in the vigor of therapy in the different experiments. The question of proper dose control is important in another context. One of the potential limiting factors in the use of heterologous antiserum has been the fear that the foreign protein would cause serum sickness. Gray, Monaco, Wood, and Russell and Levey and Medawar (13) carried out elegant studies to determine if mice were capable of developing antibodies against the rabbit protein of their antilymphoid serums. Both groups found that immunosuppression was complete enough so that the appearance of antirabbit-protein antibodies was prevented or greatly reduced. These studies validated a hypothesis first suggested by Sacks, Fillipone, and Hume that the heterologous antiserum would exert a self-antidotal role in preventing serum sickness.

This concept is further strengthened by the data in the present study. The development in dogs of precipitin antibodies against normal horse serum was very rapid when nonimmune serum was employed. In contrast, the response was both delayed and attenuated with the use of globulin products prepared from immunized horses, and similar observations were made in the patients. However, these studies and those of the previous workers were for relatively short periods and do not preclude this complication with chronic therapy. The possible clinical dilemma in terms of long term prolongation of organ homografts is evident. To avoid the threat of serum sickness, very complete immunosuppression is required. If such total or near total immunosuppression is achieved, it may be that morbidity similar to that in Monaco's mice will be encountered in man.

In addition, the question of renal injury by chronic injection of foreign protein appears to be equally important. Although previous studies with administration of antilymphoid serum have not documented this complication, it is well known that similar experimental techniques may produce glomerular injury. Dixon, Feldman and Vazquez showed that the critical factor for production of lesions was that the animal should produce barely sufficient antibody to neutralize the injected antigen. The minor rises in antibody titer observed after administration of antilymphoid agents to our dogs were clearly sufficient in many instances to produce renal damage following the formation of circulating antigen-antibody complexes. The kidney is merely a receptacle for these complexes and is not a specific immunologic target. Conceivably, the most useful role of the antilymphoid substances in clinical immunosuppressive regimens will only be for a short term course of therapy during the first critical weeks or months after operation. This is a particularly important possibility since Feldman has shown in the rabbit that the glomerular damage, once established, persists for more than a year after termination of antigen administration.

Finally, additional information is badly needed concerning the most effective methods of raising antiserum. In our experiments, heavy reliance was placed upon the spleen as an antigen source for reasons of convenience. However, Nagaya and Sieker have claimed that rabbit antiserums were twice as effective in preventing skin homograft rejection in mice when immunization was with mouse thymocytes as opposed to lymph node lymphocytes. The question they have raised of the superiority of different lymphoid tissues as antigen will require careful study, as will the possibility that safer and more potent serums can be raised in animals other than the horse.

Summary

Horses were immunized against dog or human lymphoid tissue with multiple subcutaneous injections of fresh lymph nodes, thymus, and spleen. The equine antibody response, as gauged by the titer of leukoagglutinating antibodies, was small when the immunizing dose of donor cells ranged from 0.5 to 19 billion. When this dose was increased to as much as 200 billion spleen cells, the titers rose rapidly to as high as 1:16,384. With in vitro testing, the antibody tended to agglutinate equally the white cells present in white cell pack and pure lymphocyte suspensions obtained from the thoracic duct. A weak cross species agglutination was observed, indicating a lack of absolute species specificity. Furthermore, the ability to agglutinate white cells of different members of the lymphoid donor species was variable, suggesting a degree of individual specificity. An undesired collateral response was a rise in the horse hemagglutinin titer.

Absorption of the immune horse serum with the red cells or serum from the species that had donated the lymphoid tissue for immunization did not alter the antiwhite cell titer. In contrast, repeated absorption with either kidney or liver resulted in a titer loss of approximately 90 per cent. This finding indicates that most of the antigens in the lymphocyte are represented in other tissues, and that the antiserums are capable of reacting with other than lymphoid tissues.

Fractionation of the antilymphoid antibody was carried out with ammonium sulfate precipitation. The most effective concentration was at 0.4 saturation, which when done twice allowed recovery of approximately half of the antibody with a minimum of contamination with extraneous horse protein. Further studies with column chromatography, electrophoresis, and immunoelectrophoresis demonstrated the presence of agglutinating antibodies in the gamma G, T equine, and beta globulin fractions.

Various antilymphoid products were tested in vivo. In dogs, unabsorbed antilymphoid plasma, antilymphoid serum which was partially absorbed with red cells, antilymphoid serum which was completely absorbed with red cells, serum, liver, or kidney, and the raw globulin precipitated from absorbed antiserum all had a lymphopenic effect. With the progressive stages of refinement, the morbidity from therapy was reduced. Inasmuch as immune horse globulin was well tolerated in dogs, a comparable product was developed and used for 7 patients who were prospective recipients of renal homografts. In both dogs and man, a low titer response of precipitin antibodies to normal horse serum was documented.

In the lymphoid tissues of the treated animals small lymphocytes were replaced by large and medium-sized proliferating cells with pyroninophilic cytoplasm, and germinal center formation was common. These findings are compatible with Levey and Medawar's hypothesis that at least one action of antilymphoid agents is to stimulate transformation of lymphocytes and that its immunosuppressive effect is not dependent upon lymphocyte killing.

Although changes in blood urea nitrogen could be produced only by giving antilymphoid serum intravenously, there was a high incidence of histologic renal damage with various antilymphoid agents after all routes of administration. The renal injury consisted of dense accumulations of horse and dog gamma globulin, together with complement, along the subepithelial aspects of the renal glomerular capillary basement membranes. Once developed, these deposits persisted for at least 28 days after injections were stopped. The incidence of these lesions was highest when the antilymphoid serum was given intravenously. Prior absorption of the serum with dog kidney and liver did not prevent the renal deposits from occurring.

Acknowledgments

Aided by U. S. Public Health Service grants AM 06283, AM 06344, HE 07735, AM 07772, AI 04152, FR 00051 and FR 00069 and by a grant from the Medical Research Council of Great Britain.

Contributor Information

Yoji Iwasaki, Chiba, Japan

K. A. Porter, Department of Pathology, St. Mary's Hospital and Medical School, London, England

James R. Amend, Department of Surgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine and the Denver Veterans Administration Hospital, Denver, Colorado

Thomas L. Marchioro, Department of Surgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine and the Denver Veterans Administration Hospital, Denver, Colorado

Volker Zühlke, Cologne, Germany

Thomas E. Starzl, Department of Surgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine and the Denver Veterans Administration Hospital, Denver, Colorado

References

- 1.Chew WB, Lawrence JS. Antilymphocytic serum. J Immun, Balt. 1937;33:271. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruickshank AH. Anti-lymphocytic serum. Brit J Exp Path. 1941;22:126. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dausset J. Histocompatibility Testing. Washington, D. C.: National Academy of Sciences; 1965. Technique for demonstrating leukocyte agglutination; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon FJ, Feldman JD, Vazquez JJ. Experimental glomerulonephritis; the pathogenesis of a laboratory model resembling the spectrum of human glomerulonephritis. J Exp M. 1961;113:899. doi: 10.1084/jem.113.5.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman JD. Pathogenesis of ultrastructural glomerular changes induced by immunologic means. In: Grabar P, Miescher PA, editors. Immunopathology; Third International Symposium; Basle: Schwabe and Co.; 1963. p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gowans JL, McGregor DD. The immunological activities of lymphocytes. Progr Allergy. 1965;9:1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray JG, Monaco AP, Russell PS. Heterologous mouse anti-lymphocyte serum to prolong skin homografts. Surgical Forum; Clinical Congress 1964; Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 1964. p. 142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray JG, Monaco AP, Wood ML, Russell RS. Studies on heterologous anti-lymphocyte serum in mice—I, In vitro and in vivo properties. J Immun, Bait. 1966;96:217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris TN, Hummeler K, Harris S. Electron microscopic observations on antibody-producing lymph node cells. J Exp M. 1966;123:161. doi: 10.1084/jem.123.1.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inman DR, Cooper EH. The relation of ultrastructure to DNA synthesis in human leukocytes—I, atypical lymphocytes in phytohaemagglutinin cultures and infectious mononucleosis. Acta haemat. 1965;33:257. doi: 10.1159/000209536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki Y, Talmage D, Starzl TE. Humoral antibodies in patients after renal homo-transplantation. Transplantation. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196703000-00008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeejeebhoy HF. Immunological studies on the rat thymectomized in adult life. Immunology. 1965;9:417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey RH, Medawar PB. Some experiments on the action of anti-lymphoid antisera. Ann N York Acad Sc. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Idem. Nature and mode of action of antilymphocyte antiserum. Proc Nat Acad Sc, U S. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metchnikoff E. Etudes sur la resorption des cellules. Ann Inst Pasteur, Par. 1899;13:737. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monaco AP, Wood ML, Gray JG, Russell PS. Studies on heterologous antilymphocyte serum in mice—II, effect on the immune response. J Immun, Balt. 1966;96:229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monaco AP, Wood ML, Russell PS. Effect of adult thymectomy on the recovery from immunological depression induced by anti-lymphocyte serum. Surgical Forum; Clinical Congress 1965; Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 1965. p. 209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Movat HZ, Fernando NVP. The fine structure of the lymphoid tissue during antibody formation. Exp Molec Path. 1965;4:155. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(65)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagaya H, Sieker HO. Allograft survival; effect of antiserums to thymus glands and lymphocytes. Science. 1965;150:1181. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3700.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pappenheimer AM. Experimental studies upon lymphocytes—II, the action of immune sera upon lymphocytes and small thymus cells. J Exp M. 1917;26:163. doi: 10.1084/jem.26.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payne R. Histocompatibility Testing. Washington, D. C.: National Academy of Sciences; 1965. An agglutination technique for the demonstration of leukocyte isoantigens in man; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Putnam CW, Terasaki PI, Kashiwagi N, Iwasaki Y, Marchioro TL, Starzl TE. The demonstration of interspecies reactivity and intraspecies specificity of antilymphoid globulin. Transplantation. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacks JH, Fillipone DR, Hume DM. Studies of immune destruction of lymphoid tissue—I, lymphocytotoxic effect of rabbit-anti-rat-lymphocyte anti-serum. Transplantation. 1964;2:60. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheidegger JJ. Une micro-méthode de l'immunoélectrophorèse. Internat Arch Allergy. 1955;7:103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sober HA, Peterson EA. Protein chromatography on ion exchanger cellulose. Fed Proc, Balt. 1958;17:1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Porter KA, Iwasaki Y, Cerilli JC. The use of heterologous antilymphoid agents in canine renal and liver homotransplantation, and in human renal homotransplantation. Surg Gyn Obst. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waksman BH, Arbouys S, Arnason BG. The use of specific “lymphocyte antisera” to inhibit hypersensitive reactions of the delayed type. J Exp M. 1961;114:997. doi: 10.1084/jem.114.6.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodruff MFA. The Transplantation of Tissues and Organs. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodruff MFA, Anderson NF. Effect of lymphocyte depletion by thoracic duct fistula and administration of anti-lymphocytic serum on the survival of skin homografts in rats. Nature, Lond. 1963;200:702. doi: 10.1038/200702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Idem. The effect of lymphocyte depletion by thoracic duct fistula and administration of anti-lymphocytic serum on the survival of skin homografts in rats. Ann N York Acad Sc. 1964;120:119. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb34710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]