Abstract

Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH) is a variant of viral hepatitis reported in hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infected liver, renal or bone transplantation recipients and in leukemia and lymphoma patients after conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy. FCH constitutes a well-described form of fulminant hepatitis having extensive fibrosis and severe cholestasis as its most characteristic pathological findings. Here, we report a case of a 49-year-old patient diagnosed with small-cell lung cancer who developed this condition following conventional chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression. This is the first reported case in the literature of FCH after conventional chemotherapy for a solid tumor. In addition to a detailed report of the case, a physiopathological examination of this potentially life-threatening condition and its treatment options are discussed.

Keywords: Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis, Immuno-suppression, Chemotherapy, Lung cancer, Hepatitis B virus, Lamivudine

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a well-known pathogen which can cause fulminant hepatitis in some patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Patients who have completely recovered from acute hepatitis can harbor a latent HBV infection for decades[1].

Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH) is a recognized unique variant of viral hepatitis which was originally reported in 1991 by Davies et al[2] in HBV-infected recipients of liver allografts. Other authors have also reported FCH cases in HCV-infected recipients after liver transplantation[3] and in renal[4], cardiac[5] or bone marrow transplanted patients[6] as well as in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[7]. FCH has additionally been reported secondary to hepatitis C allograft reinfection[8].

However, to our knowledge only 3 cases of FCH have been reported after conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy. Nonetheless, all of them were diagnosed with non-solid tumors (acute myelogenous leukemia[9], acute lymphoblastic leukemia[10] and low grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[11]). FCH is associated with extremely high mortality[12].

We report a case of a patient diagnosed with small-cell lung cancer who developed FCH under chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression.

CASE REPORT

This is a case of a 49-year-old male with a 38 pack-year smoking history and a past medical history of hepatitis B. He had not received previous blood transfusions. At the time of admission, the patient presented with pain in the right hemithorax. Initial investigations included thoracic X-ray, thoracic computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging demonstrating right pleural effusion, right upper lobe atelectasia, mediastinal adenopathies and liver and bone metastases. After a bronchoscopy-guided biopsy, he was diagnosed with extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer. The patient accepted chemotherapy and a combination regimen of cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m2 (days 1-3), adriamycin 40 mg/m2 (day 1), cisplatin 100 mg/m2 (day 2), vincristine 2 mg (day 3) and etoposide 100 mg/m2 (days 1-3) was administered. After the first cycle, the patient presented with grade IV febrile neutropenia in spite of pegfilgrastim prophylaxis. For this reason, a 20% dose reduction was applied on the second cycle. Doses were escalated to the original levels in the third cycle, during which the patient presented with elevation of glutamic oxalacetic transaminase (GOT) (232 UI/mL) and glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) (639 UI/mL).

Following the third cycle, a PET-CT scan showed a radiological complete response. In contrast, the patient showed persistent elevation of transaminases (GOT: 198 UI/mL; GPT: 400 UI/mL).

After administration of the fourth cycle, he developed grade 4 thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. A complete serological study was performed demonstrating hepatitis B reactivation (HBsAg, HBeAb and HBcAb IgG positive). Despite treatment with the nucleoside analogue entecavir and methylprednisolone, the hepatitis progressed towards acute hepatic failure (GOT: 1879 UI/mL; GPT: 2663 UI/mL; total bilirubin: 42 mg/dL; direct bilirubin: 37 mg/dL; indirect bilirubin: 5 mg/dL; prothrombin time: 10%). A liver biopsy was not performed, due to thrombocytopenia and clotting time elevation.

The patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit and received plasma exchange, vasoactive drugs and wide spectrum antibiotics (piperacillin-tazobactam). In spite of these therapies, he died a month after the last chemotherapy cycle from acute liver failure.

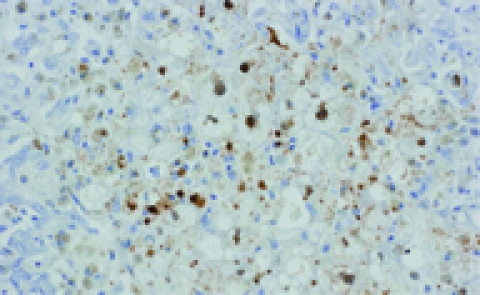

The autopsy showed residual tumor in the mediastinum and peribronchial nodes, a hepatic reaction and fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis. The microscopic study revealed marked hepatocyte degeneration, whereas the immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated hepatocytes diffusely stained for HBsAg following both intracytoplasmic and cytoplasmic membranous patterns and nuclear and intracytoplasmic HBcAg staining patterns (Figure 1). Serum levels of HBV DNA polymerase were 17 857 100 UI/mL.

Figure 1.

Liver necropsy stained with antibody against hepatitis B core antigen. FCH is also characterized by massive expression of hepatitis B core antigen (nuclear and cytoplasmic).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of FCH after conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy treatment in a patient diagnosed with a solid tumor. There have only been 3 case reports published of FCH patients who had received conventional chemotherapy for hematological malignancies. FCH is a subtype of viral hepatitis in HVB-infected patients which is associated with extremely high mortality.

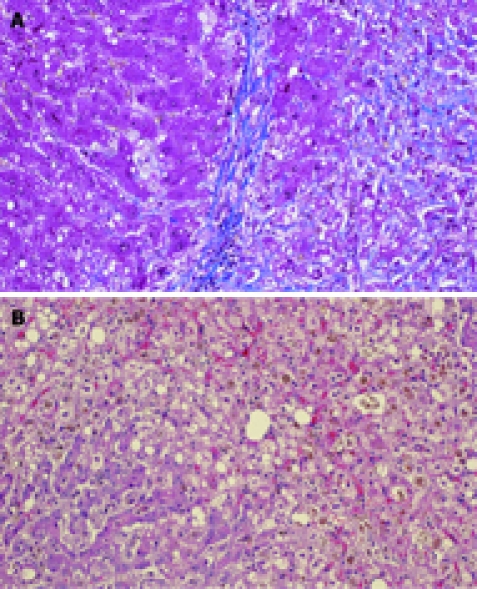

Degeneration of hepatocytes with minimal infiltration of inflammatory cells (which is clearly distinguishable from other fulminant hepatitis), extensive fibrosis and severe cholestasis are the most characteristic pathological findings. Liver parenchymatous changes include hepatocyte swelling and cholestasis with marked ductular reaction[13] (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Liver necropsy. A: Stained with Mason trichromic; B: Stained with eosin-hematoxylin. FCH is characterized by marked hepatocellular swelling, lobular disarray and cholestasis, with only mild or no portal or lobular inflammation, combined with acute cholangiolitis and fibrosis surrounding the cholangioles.

Although the ultimate physiopathological mechanism in this condition remains elusive[14], the extremely high levels of viral replication, the massive HBcAg and HBsAg expression in the liver and the non-significant inflammatory component suggest a direct HBV cytopathologic effect. The accumulation of viral antigens in the endoplasmic reticulum damages vital cell functions leading to cell death[13]. Although specific treatment protocols are lacking, a few case reports have described a clinical benefit after administration of ganciclovir/foscarnet antiviral therapy[15] in these patients. Additionally, other reports describe the efficacy of lamivudine, a nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor, in the treatment of chronic hepatitis[12] and in prophylaxis of chronic hepatitis and FCH[16]. Moreover, lamivudine has been recommended by some authors for the prophylaxis of HBV hepatitis in carrier subjects undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy for lymphoid malignancies[17], although no data from clinical trials are available.

This case report suggests that viral analysis might be indicated in patients presenting with solid tumors before initiating intensive chemotherapy regimens. In addition, prophylactic lamivudine should be considered in HVB chronic infection carrier patients (HBsAg positive and/or HBcAb IgG positive) in this setting.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Chris JJ Mulder, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, VU University Medical Center, PO Box 7057, 1007 MB Amsterdam, The Netherlands

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Yin DH

References

- 1.Muñoz Bartolo G. [Hepatitis B. Chronic hepatitis. Outcome and treatment] An Pediatr (Barc) 2003;58:482–485. doi: 10.1016/s1695-4033(03)78097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies SE, Portmann BC, O'Grady JG, Aldis PM, Chaggar K, Alexander GJ, Williams R. Hepatic histological findings after transplantation for chronic hepatitis B virus infection, including a unique pattern of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1991;13:150–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furuta K, Takahashi T, Aso K, Hoshino H, Sato K, Kakita A. Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis in a liver transplant recipient with hepatitis C virus infection: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:389–391. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03976-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth JC, Goldin RD, Brown JL, Karayiannis P, Thomas HC. Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis in a renal transplant recipient associated with the hepatitis B virus precore mutant. J Hepatol. 1995;22:500–503. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Izquierdo MT, Almenar L, Zorio E, Martínez-Dolz L. [Viral hepatitis C-related fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis after cardiac transplantation] Med Clin (Barc) 2007;129:117–118. doi: 10.1157/13107371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooksley WG, McIvor CA. Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis and HBV after bone marrow transplantation. Biomed Pharmacother. 1995;49:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(96)82604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang JW, Wright TL, Lau JY. Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis in patient with HIV and hepatitis B. Lancet. 1993;342:1175. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92160-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saleh F, Ko HH, Davis JE, Apiratpracha W, Powell JJ, Erb SR, Yoshida EM. Fatal hepatitis C associated fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis as a complication of cyclophosphamide and corticosteroid treatment of active glomerulonephritis. Ann Hepatol. 2007;6:186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima H, Abei M, Takei N, Mukai Y, Hasegawa Y, Iijima T, Nagasawa T. Fatal reactivation of hepatitis B virus following cytotoxic chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia: fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69:101–104. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HK, Yoon GS, Min KS, Jung YW, Lee YS, Suh DJ, Yu E. Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis: a report of three cases. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:111–114. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasmuth JC, Fischer HP, Sauerbruch T, Dumoulin FL. Fatal acute liver failure due to reactivation of hepatitis B following treatment with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab for low grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Eur J Med Res. 2008;13:483–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan TM, Wu PC, Li FK, Lai CL, Cheng IK, Lai KN. Treatment of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis with lamivudine. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Y, Luo K, Yu L. [Clinical and histological features of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2002;10:434–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon LR, Crawford JM. Early histologic changes in fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:219–226. doi: 10.1002/lt.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angus P, Richards M, Bowden S, Ireton J, Sinclair R, Jones R, Locarnini S. Combination antiviral therapy controls severe post-liver transplant recurrence of hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1993;8:353–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1993.tb01527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu SC, Yan LN, Li B, Wen TF, Zhao JC, Cheng NS, Liu C, Liu J, Wang XB, Li XD, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis of liver allograft HBV reinfection in HBV related cirrhotic patients after liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi G, Pelizzari A, Motta M, Puoti M. Primary prophylaxis with lamivudine of hepatitis B virus reactivation in chronic HbsAg carriers with lymphoid malignancies treated with chemotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:58–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]