Abstract

Objectives

To compare Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS) levels in serum obtained during the early follicular phase to those obtained randomly during the menstrual cycle. To determine if HIV infection influences early follicular MIS levels, an early marker of ovarian aging.

Design

A cross-sectional study

Setting

Women’s Interagency HIV Study, a multicenter prospective study

Patients

Serum samples obtained from 263 (187 HIV infected and 76 uninfected) participants of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study who reported menstrual bleeding during the preceding 6 months and who were not taking exogenous hormones.

Interventions

Early follicular (cycle day 2–5) MIS samples were compared with serum samples that had been obtained without regard to menstrual cycle phase. Comparison samples were obtained within 6 weeks prior to and/or within 3 to 6 months after the early follicular samples. Early follicular FSH, estradiol, inhibin B and MIS levels were also compared between the HIV infected and uninfected women.

Main Outcomes

Correlation between early follicular MIS and prior and subsequent samples. Comparison of serum markers of ovarian reserve between HIV positive and negative women.

Results

MIS values from early follicular and other random cycle phases were highly correlated with each other (r>0.93, p<0.0001). In multivariate analysis, increased age and FSH level and lower inhibin B levels were associated with lower MIS level; MIS values did not vary by HIV serostatus.

Conclusions

MIS without regard to cycle phase was similar during early follicular phase and highly correlated with early follicular FSH and inhibin B in women with and without HIV. Measurement of serum MIS offers a simplified method of determining ovarian reserve using specimens obtained without menstrual phase timing. Furthermore, using biologic measures of reproductive aging, we found no evidence that HIV infection influences ovarian aging.

Background

Depletion of ovarian follicles defines the process of women’s reproductive aging and is responsible for aging-associated decreases in fertility and gonadal steroids. Recent studies indicate that Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS) (also known as Anti-Müllerian hormone-AMH), may offer the most accurate, simple and noninvasive method for determining ovarian follicle reserve and reproductive aging (1–11). At present a variety of methods are used to assess ovarian reserve depending largely on the clinical or research setting. Vaginal ultrasound with antral follicle counts is accurate, but expensive and cumbersome. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is correlated with age-related declining fertility. It is a commonly used measure of ovarian aging, but is subject to variance with cycle phase, exogenous hormone use, drinking alcohol and tobacco smoking (12–14). Early follicular serum inhibin B, has been demonstrated to be a more sensitive indicator of ovarian aging (15–17), but is also influenced by cycle phase, as well as body mass and perhaps race (18).

Both FSH and inhibin B reflect activity of gonadotropin-dependent dominant follicles and are insensitive to the remaining pool of gonadotropin-independent quiescent follicles. However, it is the size and function of this remaining pool that are the direct determinants of future ovarian function. MIS is produced by the gonadotropin-independent pool of preantral and small antral follicles and is thus not dependent on cyclic development of individual follicles. Furthermore, MIS is not altered when follicular development is suppressed by exogenous sex steroids. Despite the potential improved utility of MIS as a marker of ovarian reserve over FSH and inhibin B, its behavior in the context of HIV infection is unclear.

HIV infection, which is associated with neurologic, immunologic, inflammatory and metabolic perturbations, could influence menstrual pattern and ovarian reserve. Several research groups have reported the occurrence of, or the lack of, altered patterns of reproductive aging in HIV infected women (19–25). These studies have utilized self reported menopause and menopausal symptoms, menstrual calendars, and/or randomly-timed FSH levels as measures of reproductive aging, which are recognized to be subject to bias and imprecision. We utilized the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) cohort as a platform to test the hypothesis of whether MIS measured in variable phase specimens correlates with early follicular MIS levels. In addition, the WIHS cohort allowed us to investigate whether any correlation between untimed and early follicular MIS levels remains in the context of HIV infection.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This study was nested in the WIHS, the largest ongoing multicenter prospective cohort study of HIV infection and related health conditions among HIV seropositive women and at-risk seronegative comparison women in the United States. The protocols, procedures, and baseline results of the WIHS have been previously described (26). The WIHS enrolled HIV participants between October, 1994 and November, 1995, and between October 2001 and September 2002, at six study sites (Bronx, NY; Brooklyn, NY; Chicago, IL; Los Angeles, CA; the San Francisco Bay Area and the Washington, D.C. area). The HIV-infected group was similar in terms of race/ethnicity, HIV exposure factors and age to AIDS cases among US women reported in 1995 and the seronegative group was comparable to the seropositive group in terms of age, race/ethnicity, and a number of sociodemographic characteristics (26,27). Semiannual WIHS study visits include extensive interview, clinical exam, and collection of biological specimens at any time during the menstrual cycle when bleeding is not present. In addition, during 2003–2005 women who reported having experienced menstrual bleeding during the preceding 6 months and who were not taking exogenous hormones, were asked to notify study staff the day their next cycle began, and then return for study phlebotomy on day 2–5 of that cycle; and hence all laboratory values obtained on this day 2–5 visit are referred to as early follicular visits. Early follicular (cycle day 2–5) samples were compared with serum samples that had been obtained without regard to menstrual cycle phase. Comparison samples were obtained within 6 weeks prior to and within 3 to 6 months after the early follicular samples. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after approval by the human subjects protection committees at participating institutions. Included in this study are all women for whom specimens were available from both an early follicular visit and a core WIHS visit.

Assay Methods

HIV infection was detected by EIA with Western blot confirmation (26). Estradiol levels were measured on serum samples by the Coat-A-Count solid phase radioimmunoassay (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) with 6-dilution calibration standards and a zero control. FSH levels were measured on serum samples by the ADVIA Centaur FSH two-site immunoassay (Bayer Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY) with two-point calibration. Both assays were performed by QUEST Diagnostics Laboratories.

MIS and inhibin B levels were measured at Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island. Serum samples were assayed in duplicate by ELISA for MIS/AMH (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc. Webster, TX). Briefly, samples were incubated in microtiter wells with anti-MIS/AMH antibody. After incubation and washing, the wells were treated with a biotin-labeled antibody followed by streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was used as substrate and a dual wavelength absorbance was measured at 450 and 620nm. Samples from each patient were run on the same assay. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were <15% and the limit of detection was 0.10 ng/mL.

For inhibin-B measurement, a subset of serum samples (day 2–5 only) were also assayed in duplicate using an ELISA method (Oxford Bio-Innovations-DSL, UK). Briefly, samples were pretreated with SDS, boiled for 3 minutes and incubated with hydrogen peroxide before addition to microtiter wells. After overnight incubation with anti-inhibin BB antibody, the wells were washed and incubated with an alkaline phosphatase-labeled, inhibin alpha subunit antibody. Substrate was added and absorbance was measured at 405 and 620nm. The assay is highly specific for dimeric inhibin B, with negligible cross-reactivity reported for pro-alpha C subunit or activins, and approximately 1% cross-reactivity with inhibin A. The intra- and inter-assay CVs were <15% and the limit of detection was 16 pg/mL. The HIV status of the patients was unknown to the technician performing the assays.

Statistical Analysis

Early follicular phase characteristics were compared between women with MIS values above and below the median, as well as between those with and without HIV infection, via chi-square analysis for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. All characteristics were measured at the early follicular phase study visit. Menopausal stage was defined via an algorithm combining self-reported menstrual history and pregnancy. Early transition signaled decreased cycle predictability, and was defined as women who either: (a) reported at two consecutive visits that they had skipped a period in the past six months, (b) reported at two consecutive visits that they had periods at least 3 days early or 3 days late in the past six months, or (c) reported at one visit both having skipped a period and having had an early or late period in the past six months. Late transition signaled 6–11 months of amenorrhea and was defined as women who reported no period in the past six months and were not currently pregnant and had no pregnancies since their last visit (since participants were allowed one skipped semiannual visit, we could assess amenorrhea over the past 11 months). Menopause was defined as ≥ 12 months of amenorrhea and was defined as two consecutive visits at which a woman reported no period in the past six months, and no pregnancies.

Mean MIS values across visits and between HIV strata were also compared via t-tests. Mean early follicular phase FSH, estradiol and inhibin B values were compared between HIV-infected and HIV-negative women using t-tests. Pearson’s correlation coefficients, along with their corresponding p-values, were obtained in examining correlations of log-transformed MIS values between visits. Finally, univariate and multivariate linear regression models were constructed to investigate independent predictors of MIS, adjusting for potential confounders. We examined potential interactions between current smoking and HIV infection, and also between smoking and age, in the multivariate models. In addition, separate subgroup analyses were conducted, restricting the sample to HIV-infected women only, in order to assess any associations between CD4+ lymphocyte count, HIV viral load, a prior clinical AIDS diagnosis (CDC criteria excluding CD4 cell count), and use of antiretroviral therapies reported by the participant at the core WIHS visit with MIS values. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Complete early follicular visit data were available at the time of analysis for 263 women, 187 (71.1%) of whom were HIV-infected. Characteristics of those women from the time of the day 2–5 sample draw can be seen in Tables 1a (stratified by MIS above/below the median value) and 1b (stratified by HIV status). Participants ranged in age from 20 to 54 years (mean = 37.1), were 68.4% Black and 23.6% Latina. Current cigarette smoking was reported by 55.5% of participants, and cohort participants tended to be over ideal weight, with the mean BMI (29.1) being just under the lower limit for obesity. Less than ten percent (8.8%) had never been pregnant, and almost 40% had at least three children. Very few participants (6.8%) reported having had ovarian surgery. The majority of participants (92.8%) were either premenopausal or were in early transition. Compared to women with MIS values greater than or equal to the median (1.03 ng/ml), women with values below the median were significantly (p<0.05) older (mean age 41.7 versus 32.6 years), more likely to smoke, had higher FSH and lower Inhibin B, and reported higher gravidity and parity. HIV-infected participants differed from the seronegatives only in that they had a significantly higher frequency of reported night sweats. While mean values of inhibin B, FSH and estradiol were lower among HIV-infected women, none of these differences was statistically significant.

Table 1.

| Table 1a. Early Follicular Phase Characteristics of 263 Participants in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, April 2003 – February 2005 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (N = 263) | MIS <1.03 ng/ml† (n = 131) | MIS ≥ 1.03 ng/ml (n = 132) | p-value* |

| HIV Serostatus§ | ||||

| Seronegative | 76 (28.9) | 36 (27.5) | 40 (30.3) | 0.614 |

| Seropositive | 187 (71.1) | 95 (72.5) | 92 (69.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Age‡ | 37.1 ± 0.43 | 41.7 ± 0.44 | 32.6 ± 0.50 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Race§ | ||||

| White | 13 (4.9) | 5 (3.8) | 8 (6.1) | 0.756 |

| Black | 180 (68.4) | 90 (68.7) | 90 (68.2) | |

| Latina | 62 (23.6) | 31 (23.7) | 31 (23.5) | |

| Other | 8 (3.0) | 5 (3.8) | 3 (2.3) | |

|

| ||||

| BMI‡ | 29.1 ± 0.49 | 29.2 ± 0.72 | 29.1 ± 0.67 | 0.886 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking§ | ||||

| Current | 146 (55.5) | 77 (58.8) | 69 (52.3) | 0.035 |

| Former | 35 (13.3) | 22 (16.8) | 13 (9.9) | |

| Never | 82 (31.2) | 32 (24.4) | 50 (37.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Gravidity (# pregnancies) § | ||||

| None | 23 (8.8) | 9 (6.9) | 14 (10.6) | 0.013 |

| 1–2 | 55 (20.9) | 19 (14.5) | 36 (27.3) | |

| ≥3 | 185 (70.3) | 103 (78.6) | 82 (62.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Parity (# children) § | ||||

| None | 49 (18.6) | 16 (12.2) | 33 (25.0) | 0.009 |

| 1–2 | 109 (41.4) | 53 (40.5) | 56 (42.4) | |

| ≥3 | 105 (39.9) | 62 (47.3) | 43 (32.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Ovarian surgery§ | 18 (6.8) | 12 (9.2) | 6 (4.6) | 0.138 |

|

| ||||

| Night sweats§ | 31 (11.8) | 19 (14.5) | 12 (9.1) | 0.174 |

|

| ||||

| Stage of Menopause§ | ||||

| Premenopause/early transition | 244 (92.8) | 119 (90.8) | 125 (94.7) | 0.227 |

| Late transition/menopausal | 19 (7.2) | 12 (9.2) | 7 (5.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Inhibin B‡ | 74.6 ± 4.74 | 63.4 ± 8.29 | 85.7 ± 4.51 | 0.018 |

|

| ||||

| FSH‡ | 8.0 ± 0.58 | 10.9 ± 1.10 | 5.2 ± 0.14 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Estradiol‡ | 44.6 ± 1.63 | 47.0 ± 2.87 | 42.1 ± 1.55 | 0.134 |

| Table 1b. Characteristics by HIV Serostatus of 263 Participants in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, April 2003 – February 2005 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (N = 263) | HIV Seronegative (n = 76) | HIV Seropositive (n = 187) | p-value* |

| Age‡ | 37.1 ± 0.43 | 36.1 ± 0.96 | 37.5 ± 0.47 | 0.142 |

|

| ||||

| Race§ | ||||

| White | 13 (4.9) | 3 (4.0) | 10 (5.4) | 0.371 |

| Black | 180 (68.4) | 58 (76.3) | 122 (65.2) | |

| Latina | 62 (23.6) | 13 (17.1) | 49 (26.2) | |

| Other | 8 (3.0) | 2 (2.6) | 6 (3.2) | |

|

| ||||

| BMI‡ | 29.1 ± 0.49 | 29.4 ± 0.85 | 29.0 ± 0.60 | 0.705 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking§ | ||||

| Current | 146 (55.5) | 50 (65.8) | 96 (51.3) | 0.101 |

| Former | 35 (13.3) | 8 (10.5) | 27 (14.4) | |

| Never | 82 (31.2) | 18 (23.7) | 64 (34.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Gravidity (# pregnancies) § | ||||

| None | 23 (8.8) | 9 (11.8) | 14 (7.5) | 0.245 |

| 1–2 | 55 (20.9) | 19 (25.0) | 36 (19.2) | |

| ≥3 | 185 (70.3) | 48 (63.2) | 137 (73.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Parity (# children) § | ||||

| None | 49 (18.6) | 18 (23.7) | 31 (16.6) | 0.365 |

| 1–2 | 109 (41.4) | 28 (36.8) | 81 (43.3) | |

| ≥3 | 105 (39.9) | 30 (39.5) | 75 (40.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Ovarian surgery§ | 18 (6.8) | 3 (4.0) | 15 (8.0) | 0.236 |

|

| ||||

| Night sweats§ | 31 (11.8) | 4 (5.3) | 27 (14.4) | 0.037 |

|

| ||||

| Stage of Menopause§ | ||||

| Premenopause/early transition | 244 (92.8) | 72 (94.7) | 172 (92.0) | 0.434 |

| Late transition/menopausal | 19 (7.2) | 4 (5.3) | 15 (8.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Inhibin B‡ | 74.6 ± 4.74 | 75.7 ± 5.82 | 74.2 ± 6.25 | 0.881 |

|

| ||||

| FSH‡ | 8.0 ± 0.58 | 8.5 ± 1.50 | 7.9 ± 0.54 | 0.610 |

|

| ||||

| Estradiol‡ | 44.6 ± 1.63 | 48.2 ± 3.00 | 43.1 ± 1.94 | 0.157 |

Mean ± standard error of the mean

N (%)

obtained via t-test or chi-square analysis

median split

Mean ± standard error of the mean

N (%)

obtained via t-test or chi-square analysis

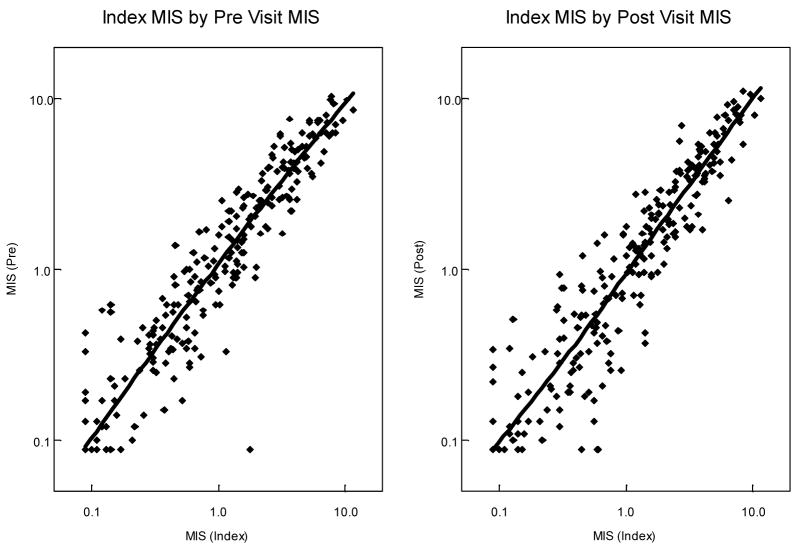

The MIS values from randomly drawn samples (the pre and post visits reach within 6 months of the index visit) were highly correlated with those from the early follicular phase samples (index visit), as seen in Figure 1. Comparing the pre visit samples with the index visit samples, MIS values were very highly correlated (r = 0.948, p<0.0001). Early follicular MIS values were also highly correlated with values from randomly drawn samples taken 3–6 months later (r = 0.944, p<0.0001). Stratified by HIV status, both pairwise visit comparisons were still significantly highly correlated (r>0.93, p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Correlation of MIS values at different times in the menstrual cycle among WIHS participants

Table 2 shows the mean (± standard error of the mean) MIS values by HIV status, at each of the three study visits (pre, index and post). HIV-infected women had significantly lower (p<0.05) MIS values than uninfected women at both the pre and index visits, and marginally lower (0.05<p<0.10) values at the post visit. In addition, while obesity was common in both cohort groups, BMI was significantly lower among the HIV-infected women (29 vs 31, p=0.027; data not shown).

Table 2.

Mean (±standard error of the mean, SEM) MIS values by HIV status at three time points

| Visit | Total | HIV+ | HIV− | p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (random) | 2.00 ± 0.14 | 1.82 ± 0.15 | 2.45 ± 0.31 | 0.043 |

| Index (day 2–5) | 1.89 ± 0.13 | 1.69 ± 0.14 | 2.36 ± 0.30 | 0.024 |

| Post (random) | 1.92 ± 0.14 | 1.77 ± 0.16 | 2.31 ± 0.31 | 0.086 |

| p-value (pre vs index) | 0.021 | 0.030 | 0.374 | |

| p-value (index vs post) | 0.465 | 0.185 | 0.655 |

comparing HIV+ and HIV− values; p-values obtained via t-tests

Next we investigated factors that were independently associated with MIS levels among our participants. Table 3 shows the results of univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses, with log-transformed MIS value as the outcome. In univariate analysis, the following factors were significantly associated with lower MIS values: older age, greater number of pregnancies/children, ovarian surgery, being in late transition or menopausal, smoking, and higher FSH levels. In addition, higher inhibin B was associated with higher MIS. In multivariate analysis, older age and higher FSH remained associated with lower MIS values, while higher inhibin B remained associated with higher MIS. Adjusting for age, FSH and inhibin B, HIV infection was not associated with MIS. All potential interactions that we examined were found not to be statistically significant (data not shown). Finally, subgroup analyses were conducted among HIV-infected women only, to investigate potential associations of virologic and immunologic factors with MIS levels. We examined CD4+ lymphocyte count, plasma HIV RNA quantity, the occurrence of an AIDS-defining condition, and receipt of antiretroviral therapy; none was found to be significantly associated with MIS (data not shown).

Table 3.

Independent correlates of early follicular phase (log) MIS values among WIHS participants

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Unadjusted Parameter Estimate (β) | p-value | Adjusted Parameter Estimate (β) | p-value |

| Age (1-yr increments) | −0.063 | <0.0001 | −0.058 | <0.0001 |

| # pregnancies | −0.074 | <0.0001 | ||

| # children | −0.155 | <0.0001 | ||

| Night sweats | −0.207 | 0.076 | ||

| Ovarian Surgery | −0.484 | 0.001 | ||

| BMI | −0.001 | 0.817 | ||

| Stage of Menopause† | ||||

| Early transition | −0.148 | 0.092 | ||

| Late transition/menopausal | −0.382 | 0.016 | ||

| Race‡ | ||||

| Black | −0.305 | 0.082 | ||

| Latina | −0.318 | 0.088 | ||

| Other | −0.083 | 0.761 | ||

| Smoking§ | ||||

| Current | −0.270 | 0.001 | ||

| Former | −0.395 | 0.001 | ||

| Inhibin B | 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| FSH | −0.024 | <0.0001 | −0.008 | 0.004 |

| Estradiol | −0.001 | 0.411 | ||

| HIV+ | −0.096 | 0.251 | ||

reference category = Premenopause

reference category = White

reference category = Never smokers

Discussion

It has been previously shown that MIS measured in the follicular phase may be an earlier and more sensitive serum marker of changes in ovarian reserve than conventional early follicular phase markers (FSH, estradiol and/or inhibin B) (4–11). Recently a prospective study of 81 Dutch volunteers who were followed for 4 years (mean age 39.6 and 43.6 at the beginning and at the end of the study, respectively) found that MIS levels were more accurate indicators of reproductive capability, determined by ultrasound measurement of antral follicle counts, than were FSH, estradiol and inhibin B (4). MIS values have been shown to have negligible variation through the menstrual cycle (intra-cycle) (28,29), between menstrual cycles (inter-cycle) (30), in response to pituitary desensitization by exogenous GnRH agonist (3,31) or during pregnancy (32). These findings are consistent with the concept that MIS serum concentrations are independent of gonadotropin secretion.

The collection of serum samples at precise times in the early follicular phase is not always feasible, both in a research and in a clinical setting. Additional visits for phlebotomy may be required and the timed specimen cannot be obtained unless menstrual bleeding occurs and is identified accurately. A serum measure of ovarian reserve that is independent of cycle phase, such as MIS, would be a great advantage in the investigation of reproductive aging in cohort studies and in clinical care, but most clinical studies to date examining MIS have focused on women with infertility. With increasing interest in the inclusion of women in clinical research and a growing women’s health research agenda, MIS measurements could be a highly useful tool for assessing reproductive age and menopausal status.

This large cohort study of women who were not pre-selected for infertility demonstrates that serum MIS sampled at varying cycle times during a prior or subsequent cycle is highly correlated with early follicular serum MIS and does not vary by HIV status. This has a potentially significant impact upon the practice of physicians who evaluate women’s ovarian reserve. The current standard for such an evaluation is limited to ultrasound antral follicle counts or early follicular serum samples (i.e., day 2–5 of the menstrual cycle) for various ovarian biomarkers such as FSH, inhibin B, estradiol and/or MIS. Since a single serum sample for MIS taken randomly during the menstrual cycle or within up to 6 months of that cycle has a high correlation with a timed sample in the early follicular phase, it may no longer be necessary to restrict serum collection to a narrow window of time to assess ovarian reserve. Most recently La Marca et al (33) demonstrated that a serum MIS on any day of the menstrual cycle is associated with ovarian response in ART. Our study suggests that an untimed serum MIS within as well as between cycles may be useful in a clinical setting of women without a history of infertility. These findings have broad clinical utility in the treatment of couples with infertility as well as in the design of clinical studies examining changes in organ system physiology secondary to ovarian aging.

Further, the data from this study suggest that HIV infected women have neither earlier nor delayed ovarian aging compared to HIV uninfected women. Although mean values for early follicular phase serum MIS concentrations were not similar between HIV-infected and HIV-negative women, multivariate analysis, which accounts for potential confounders, demonstrated that HIV status was not an independent predictor of serum MIS concentration. This is consistent with another analysis undertaken among a larger WIHS sample, which showed no difference in ovarian failure (defined as serum FSH >25 mIU/ml and amenorrhea for at least one year) by HIV status, adjusting for age, BMI, albumin and parity (27). Increasing age, early follicular serum inhibin B and FSH concentrations were independently associated with MIS level in our study, demonstrating that MIS covaries with ovarian aging and biologic measures of ovarian reserve. Thus, it appears that neither HIV infection nor antiretroviral therapies accelerates ovarian aging with its concomitant morbidities of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease and urogenital atrophy.

Measurement of serum MIS offers a simplified method of determining ovarian reserve using specimens obtained without menstrual phase timing. The fact that serum MIS is independent of gonadotropin secretion highlights its clinical relevance and potential benefits of being randomly sampled during the menstrual cycle in contrast to traditional gonadotropin dependent markers (i.e., FSH, estradiol, and inhibin B), which require early follicular phase sampling to determine ovarian reserve. These findings should be of substantial interest to those practitioners and investigators who believe ovarian reserve to be relevant to the care of their patients and/or the outcomes of their clinical research studies.

Acknowledgments

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases with supplemental funding from the National Cancer Institute, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590). Funding was also provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant UO1-HD-23632) and the National Center for Research Resources (grants MO1-RR-00071, MO1-RR-00079, MO1-RR-00083).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Seifer DB, MacLaughlin DT, Christian BP, Feng B, Shelden RM. Early follicular serum mullerian-inhibiting substance levels are associated with ovarian response during assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:468–71. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Vet A, Laven JSE, de Jong FH, Themmen APN, Fauser BCJM. Anti-Mullerian hormone serum levels: a putative marker for ovarian aging. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:357–62. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, te Velde ER, Fauser BC, Bancsi LF, Jong FH, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels: a novel measure of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3065–71. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.12.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Rooij IAJ, Broekmans FJM, Scheffer GJ, Looman CWN, Habbema JDF, de Jong FH, et al. Serum antimullerian hormone levels best reflect the reproductive decline with age in normal women with proven fertility: a longitudinal study. Fertil Sertil. 2005;83:979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanchin R, Schonauer LM, Righini C, Guibourdenche J, Frydman R, Taieb J. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone is more strongly related to ovarian follicular status than serum inhibin B, estradiol, FSH and LH on day 3. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:323–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hazout A, Bouchard P, Seifer DB, Aussage P, Junca AM, Cohen-Bacrie P. Serum anti-mullerian hormone/mullerian inhibiting substance appears to be a more discriminatory marker of ART outcome than follicular stimulating hormone, inhibin B or estradiol. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1323–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Rooij IAJ, Tonkelaar I, Broekmans FJ, Looman CWN, Scheffer GJ, de Jon FH, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone is a promising predictor for the occurrence of the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2004;11(6 Pt 1):601–606. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000123642.76105.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tremellen KP, Kolo M, Gilmore A, Lekamge DN. Anti-mullerian hormone as a marker of ovarian reserve. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45:20–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ficicioglu C, Kutlu T, Baglam E, Bakacak Z. Early follicular antimullerian hormone as an indicator of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:592–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visser JA, de Jong FH, Laven JS, Themmen AP. Anti-mullerian hormone: a new marker for ovarian function. Reproduction. 2006;131:1–9. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebner T, Sommergruber M, Moser M, Shebl O, Schreier-Lechner E, Tews G. Basal level anti-mullerian hormone is associated with oocyte quality in stimulated cycles. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2022–2026. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creinin MD. Laboratory criteria for menopause in women using oral contraceptives. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:101–4. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henrich JB, Hughes JP, Kaufman SC, Brody DJ, Curtin LR. Limitations of follicle- stimulating hormone in assessing menopause status: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999–2000) Menopause. 2006;13:171–7. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000198489.49618.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backer LC, Rubin CS, Marcus M, Kieszak SM, Schober SE. Serum follicle- stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone levels in women aged 35–60 in the U.S. population: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–1994) Menopause. 1999;6:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danforth DR, Arbogast LK, Mroueh J, Kim MH, Kennard EA, Seifer DB, et al. Dimeric Inhibin: a direct marker of ovarian aging. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:119– 23. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welt CK, McNicholl DJ, Taylor AE, Hall JE. Female reproductive aging is marked by decreased secretion of dimeric inhibin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:105– 11. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seifer DB, Scott RT, Jr, Bergh PA, Abrogast LK, Friedman CI, Mack CK, et al. Women with declining ovarian reserve may demonstrate a decrease in day 3 serum inhibin B before a rise in day 3 follicle-stimulating hormone. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:63–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Gracia CR, Kapoor S, Lin H, Liu L, et al. Follicular phase hormone levels and menstrual bleeding status in the approach to menopause. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:383–92. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller SA, Santoro N, Lo Y, Howard AA, Arnsten JH, Floris-Moore M, et al. Menopause symptoms in HIV-infected and drug-using women. Menopause. 2005;12:348–56. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000141981.88782.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fantry LE, Zhan M, Taylor GH, Sill AM, Flaws JA. Age of menopause and menopausal symptoms in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:703–11. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoenbaum EE, Hartel D, Lo Y, Howard AA, Floris-Moore M, Arnsten JH, et al. HIV infection, drug use, and onset of natural menopause. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1517–24. doi: 10.1086/497270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santoro N, Arnsten JH, Buono D, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE. Impact of street drug use, HIV infection, and highly active antiretroviral therapy on reproductive hormones in middle-aged women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:898–905. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harlow SD, Cohen M, Ohmit SE, Schuman P, Cu-Uvin S, Lin X, et al. Substance use and psychotherapeutic medications: a likely contributor to menstrual disorders in women who are seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:881–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harlow SD, Schuman P, Cohen M, Ohmit SE, Cu-Uvin S, Lin X, et al. Effect of HIV infection on menstrual cycle length. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:68–75. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200005010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cejtin HE, Kalinowski A, Bacchetti P, Taylor RN, Watts DH, Kim S, et al. Effects of Human Immunodeficiency Virus on protracted amenorrhea and ovarian dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245442.29969.5c. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Martin-Preston S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiology. 1998;9:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013–9. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook CL, Siow Y, Taylor S, Fallat ME. Serum mullerian inhibiting substance levels during normal menstrual cycles. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:859–61. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.La Marca A, Malmusi S, Giulini S, Tamaro LF, Orvieto R, Levaratti P, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone plasma levels in spontaneous menstrual cycle and during treatment with FSH to induce ovulation. Human Reproduction. 2004;19:2738–2741. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fanchin R, Taieb J, Mendez Lozano DH, Ducot B. High Reproducibility of serum anti-Mullerian hormone measurements suggests a multi-staged follicular secretion and strengthens its role in the assessment of ovarian follicular status. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:923–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fanchin R, Schonauer LM, Righini C, Frydman N, Frydman R, Taieb J. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone dynamics during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:328–332. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.La Marca A, Giulini, Orvieto R, De Leo V, Volpe A. Anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations in maternal serum during pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1569–20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.La Marca A, Giulini S, Tirelli A, Bertucci E, Marsella T, Xella S, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone measurement on any day of the menstrual cycle strongly predicts ovarian response in assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod. 2006 doi: 10.1093/humrep/del421. e publication, October 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]