Abstract

Manualized reminiscence and life review therapies are supported as an evidence-based, effective treatment for depression among older adults, but this therapeutic approach is usually individually administered and has rarely been applied in palliative care settings. We combined mutual reminiscence and life review with engagement in meaningful activity and examined the efficacy of this family-based dyadic intervention to decrease caregiving stress and increase family communication. Seventeen individuals living with chronic, life-limiting illnesses in the community and their family caregivers received three home visits with a master’s-level interventionist. During these sessions and through structured homework activities, the interventionist actively worked with the family to construct a personal Legacy Project, usually a scrapbook with photos, a cookbook, or audiotaped stories that celebrated the life of the ill individual. All participants in the intervention group initiated a Legacy Project and reported that Legacy activities improved family communication. Participation in Legacy creation also resulted in increased positive emotional experiences in patient and caregiver groups. These results are illustrated through careful examination of three case studies.

“It was the first time I allowed myself to go back and process…this gave me a chance to filter through it. I went back to look at the raw places…Ultimately, we are tied to those people.”

“I know one thing for certain. We will die one day. We cried in coming to this world. We’re gonna die. And I have come to the conclusion about that.”

These quotes from women who faced chronic, life-limiting illness and possible death illustrate the importance of time and meaningful emotional connections as individuals approach the end of life. According to Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST; Carstensen, 1998), motivational shifts caused by an increasingly limited perspective of time left to live enhance the importance and depth of emotional connections. Carstensen, Mikels, and Mather (2006) posit that empirical evidence suggests memory and attention operate, in part, in the service of emotion regulation. In late life, positive information and positive memories increase in salience (Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003; Mather & Knight, 2005). Notably, older age coincides with higher positive emotion during mutual reminiscing situations (Pasupathi & Carstensen, 2003), and increased recall of positive information is associated with better cognitive and emotional outcomes (Affleck & Tennen, 1996; Hilgeman, Allen, DeCoster, & Burgio, 2007; Tennen & Affleck, 1996). It would follow, then, that patients approaching the end of life and their family caregivers might respond more fully to interventions that harness the power of mutual reminiscing and the fulfillment of emotion-focused goals and increased positive emotions in combination with more traditional treatment components.

Although family units are the typical focus of care in palliative care settings (Allen & Shuster, 2002), few family-based intervention models exist targeting late life (Coon, Gallagher-Thompson, & Thompson, 2003; Qualls, in press). One new treatment and training model has been proposed by Qualls (in press) and is called Caregiver Family Therapy. Caregiver Family Therapy attempts to empower families to make decisions that: (1) manage safety risks and support patient autonomy; (2) assist caregivers in relating with other family members; (3) balance needs and growth of all family members according to family values; and (4) facilitate restructuring of family members’ roles and processes for providing care in ways that maximize quality of life for the patient, the caregiver, and other family members. Similarly, the Legacy Project (Allen, Hilgeman, Ege, Shuster, & Burgio, in press) examined a treatment model with the goal of promoting the needs and growth of all family members in accordance with family values (see Qualls’ point number three).

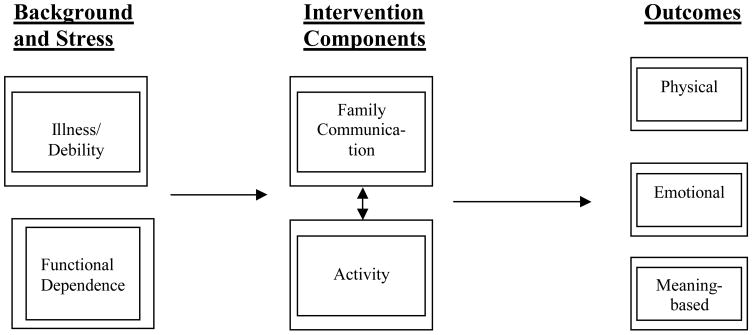

The purpose of the Legacy Project was to assess the feasibility and efficacy of a family-based intervention targeting meaning-based coping (Folkman, 1997) to decrease palliative caregiving stress and increase perceptions of meaning by palliative patients. Our theoretical model (Figure 1) is a simplification of Folkman’s (1997) stress process model. Legacy directly involves both the patient and the family in meaning-based coping through the construction of a lasting memento. Legacy incorporates evidence-based treatment components from life review and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) shown effective in reducing symptoms of depression among older adults (Scogin, Welsh, Hanson, Stump, & Coates, 2005). Specifically, memories of the patient and family caregiver are elicited via semi-structured life-review interviews (see Table 1), and these shared memories are given form through components of CBT known as behavioral activation and homework (see Table 2). Activities celebrating one’s life can maintain one’s: (1) sense of essence (continuity of self) (Cohen-Mansfield, Parpura-Gill, & Golander, 2006), (2) self-regard or pride, and (3) belief that prior roles are worthy of investment in the face of deteriorating health (Chochinov et al., 2004; Chochinov et al., 2005; Glass, DeLeon, Bassuk, & Berkman, 2006). Such activities may also increase pro-social, positive, meaningful family interaction.

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical model modified from the Revised Stress and Coping Model (Folkman, 1997).

TABLE 1.

Items used in Session 1 of the Legacy Participant Notebook.

|

Patient Questions – 4 items |

| “The things I care about and value most in my life are..” |

| “The most important people in my life have been…” |

| “I would like people to remember these things about me…” |

| “The ideas, books, music, and poems that have most influenced my life are… |

|

Caregiver Questions – 3 items |

| “My favorite memories of times with my loved one are…” |

| “The things I most want to remember about my loved one are…” |

| “The lessons/values I have learned or most associate with my loved one are…” |

| Tips for Legacy Activities |

| 1. Writing or Recording Stories on Paper |

| 2. Recording on an Audio Cassette Tape Player |

| 3. Scrapbook or Photo Album |

| 4. Video Tape Recording |

| 5. Family Cookbook |

| 6. Other Ideas |

TABLE 2.

Outline of intervention sessions (Allen & Hilgeman, 2003).

| Session 1: Deciding on a Personal Legacy |

| Goals for this Session |

| Problem Solving Step 1. |

| Reflection Questions |

| Note to the Family Member/Caregiver |

| Problem Solving Step 2. |

| Brainstorming Activity |

| Tips for Legacy Activities |

| Writing or Recording Stories on Paper |

| Recording on an Audio Cassette Tape Player |

| Scrapbook or Photo Album |

| Video Tape Recording |

| Family Cookbook |

| Other Ideas |

| Problem Solving Step 3. |

| Pro’s and Con’s of 3 Ideas |

| Problem Solving Step 4a |

| Choosing a Personal Legacy |

| Session 2: Constructing Your Personal Legacy |

| Problem Solving Step 4b. |

| Finding a different Legacy Option |

| Step 1. |

| Step 2. |

| Step 3. |

| Step 4a. |

| Session 3: Evaluation of Legacy Activity |

| Goals for this Session |

| Problem Solving Step 5. |

| Questions to Consider |

| Problem Solving Step 6. |

As shown in Table 2, during three in-home sessions Legacy interventionists led patient-family caregiver dyads through the steps of brainstorming potential projects, evaluating the positive and negative aspects of each potential Legacy, and problem-solving to limit the choices to one activity that was considered “doable” and mutually acceptable to both members of the dyad as representing the patient’s life. The Legacy interventionist’s job was to facilitate the dyad’s mutual understanding of each other’s needs (e.g., Qualls, in press) in their joint commitment to complete one tangible Legacy. During the third Legacy intervention session, the majority of time involved reviewing progress on the Legacy and evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention from the perspective of each participating family member.

Most Legacy projects enacted by our seventeen families in our pilot study (Allen et al., in press) took the form of scrapbooks, photo albums, or cookbooks. Three out of 17 families (18%) reported active participation of at least one family member in addition to the patient and family caregiver. All participants in the intervention group initiated a Legacy activity and reported that Legacy improved family communication. Across participants, the intervention reduced caregiving stress and improved patients’ symptom burden and sense of meaning. Length of treatment from baseline to post-intervention assessment was typically nine to ten weeks.

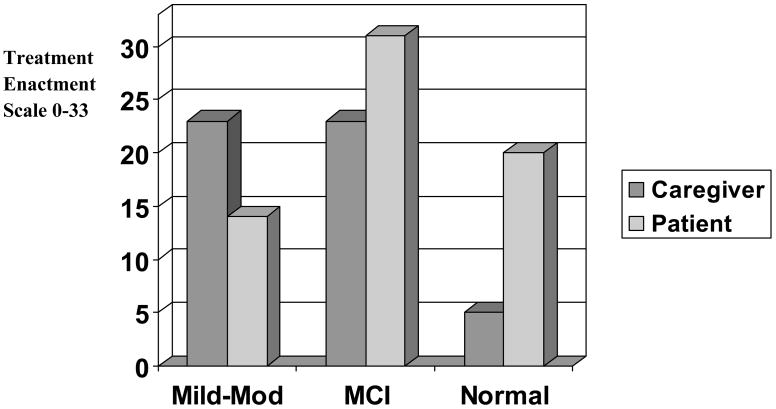

As shown in Figure 2, active participation by patients and family caregivers in constructing the Legacy varied based on the cognitive functioning of the patient, as measured by the Mini Mental State Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). Individuals with chronic, life-limiting illnesses and receiving palliative care in the community may experience cognitive decline and other health-related deficits that necessitate the involvement of family caregivers in interventions designed to maximize patient well-being. The following three case examples from the Legacy Project illustrate variability in the cognitive functioning of the patient, even within a given case across time. Two out of three of these patients died after initiating the Legacy intervention, prior to post-intervention assessment.

FIGURE 2.

Treatment enactment by patients and caregivers as a function of patient score on the Mini-Mental State Exam (Folstein et al., 1975).

CASE 1

Mr. Patient, age 67, had 16 years of education and reported his health as poor after multiple strokes that greatly limited his mobility and resulted in disinhibition within his family interactions. Mrs. Patient, age 65, had 12 years of education and reported her health as good. Mr. and Mrs. Patient were Caucasian. Although Mrs. Patient reported affiliation with a local Baptist church, Mr. Patient reported that he was spiritual but not religious.

During the baseline assessment and interview, it was clear that Mr. Patient was eager to get started on his Legacy, but he also was loquacious and circumstantial in his verbal interactions. Confined to bed, it was clear that Mr. Patient would need significant assistance from his wife in completing the Legacy. In contrast, Mrs. Patient was somewhat reticent in her interactions with project staff. She expressed concern to the interventionist that her role on the project may be “overwhelming.” As the intervention sessions began, it became clear that Mrs. Patient’s reticence stemmed from Mr. Patient’s desire to have her type out his life story (on an actual typewriter) as he dictated it to her.

The interventionist worked with this husband-wife dyad to decide on a Legacy project that would meet Mr. Patient’s need to tell his “entire life story” and yet not overwhelm Mrs. Patient. This required a careful balance in allowing Mr. Patient’s self-expression while simultaneously encouraging Mrs. Patient to express her views. With the help of the Legacy interventionist, Mr. and Mrs. Patient decided that audiotaped life stories would provide Mr. Patient the opportunity to tell his story in his own words without overwhelming Mrs. Patient. Additionally, the digital audiotapes would have the added benefit of preserving Mr. Patient’s voice for his wife and family members indefinitely. Themes generated in Mr. and Mrs. Patient’s life review session included the importance of family, generativity, and mentors. Mr. Patient stated that he attributed a lot of his success in life to his first baseball coach, who “made me who I am.” Mr. Patient also remarked that it was important to him for others to remember that he “came from nothing.”

During the third Legacy intervention session, Mr. and Mrs. Patient expressed surprise at their enthusiasm for the project:

Mrs. Patient: “…it is something we can do together that takes away the stress of the day. It’s been motivating. You can relax and have fun while you’re doing it…it’s a togetherness type of thing.”

Mr. Patient: “I enjoy the devil out of that…I enjoy that more than anything. I didn’t think I’d enjoy that, but I do.”

Mrs. Patient: “At first you’re skeptical about really how beneficial it can be. But it’s been really, kind of like starting a new phase of life. It just opens something up that we ourselves haven’t been motivated to do. Y’all are kind of like a catalyst.”

Additionally, during the final session Mr. and Mrs. Patient noted the potential importance of the Legacy to future generations, particularly their children:

Mrs. Patient: “It is the fact that he’s gotten started doing it…the tapes can be saved and we’ve thought of that before because of the kids…The older they get the more nostalgic they get, and things like this will be priceless to them later on down the line.”

Mr. Patient died before the post-intervention assessment. During this assessment Mrs. Patient and her daughter related how important the Legacy tapes had become to the family and what role the taping had played in Mr. Patient’s final days. Mrs. Patient reported that, while in the hospital, Mr. Patient complained of having nothing to do, being bored in the hospital room, and wanting to do something more meaningful than watch television. He asked that Mrs. Patient bring in his digital tape recorder so that he could record more life stories. Mrs. Patient did so, and reported that although Mr. Patient’s health continued to decline, his mood improved while he was able to engage in the meaningful activity of tape recording his life story for his family. Mrs. Patient stated that, although she was upset about some of the events that happened while Mr. Patient was in the hospital and how communication with medical staff was handled, she believed the Legacy tapes had been “a blessing” to her husband and to the family at large.

As illustrated in this case example, our Legacy intervention (see Figure 1) directly targets Folkman’s (1997) concept of meaning-based coping and engages patients approaching the end of life and their family caregivers in positive reminiscing. Moreover, creating a Legacy Project actively engages the patient and caregiver in a pleasant process of generativity. Prior research has indicated that older adults treated with four weeks of reminiscence structured to target specific personal memories showed fewer depressive symptoms, less hopelessness, improved life satisfaction, and retrieval of more specific events (Serrano, Latorre, Gatz, & Montanes, 2004). Depression is linked to overall activity level and to levels of positive affect (i.e., interest, pleasure, contentment, happiness) (Lawton, 1997) which may be increased by participation in pleasant activities (Glass et al., 2006; Hopko, Armento, Chambers, Cantu, & Lejuez, 2003). Our initial data show that engagement in pleasant and meaningful activities such as the creation of Legacy Projects can improve the quality of life of individuals approaching the end of life and their families.

CASE 2

Mother and Daughter were an African American dyad with high levels of education. Mother, age 68, had 18 years of education and was pursuing a master’s degree at the beginning of the study. Daughter, age 33, had 22 years of education and reported her health as good. Although Mother reported her health as excellent, she was diagnosed with a rapidly progressing cancer during the course of participation in the Legacy Project. Of note, Mother’s cognitive status and ability to participate in the construction of the Legacy changed dramatically throughout the course of the final days of her life.

During life review, the Caucasian interventionist working with this dyad noted the emergence and importance of racial/ethnic themes including celebration of Kwanzaa and overcoming hardship and adversity. Other themes included family, the centrality of food during holiday celebrations, Mother’s individuality and style, and art. The kitchen and cooking were often mentioned as the center of family engagement and activity. With this dyad, the two completed intervention sessions had a nostalgic flavor with strong focus on both individuality and intergenerational generativity. Mother and Daughter decided to complete a combination family cookbook/scrapbook interspersed with family photos and stories.

During the first intervention session, Brother called, was placed on speaker phone and expressed his enthusiasm for the combination cookbook/family scrapbook idea. Mother stated that she wanted others to remember her “independence, generosity, and wisdom.” Daughter agreed that Mother’s sense of style and sensitivity to the meaningfulness of art was a part of what truly made Mother unique:

Daughter: “There’s nothing in here without thought. Every single one of those books on that shelf is on there for a reason. Every single piece of art has been chosen to adorn our home.”

Daughter mentioned Mother’s independence as a lesson or value that she most associated with Mother:

Daughter: “She taught me how to take care of myself. Men are nice sorts of comfort but, um, they’re not a necessity.”

Mother elaborated on her views about heterosexual relationships:

Mother: “Marriage is a business. A lot of people don’t get that…so many business matters to handle…you know, in order to operate a household or family.”

Mother and Daughter did not complete the third session of the Legacy Project. Although they began work on their family cookbook/scrapbook and maintained momentum, Mother’s illness progressed rapidly. After approximately six weeks actively combating the malignancy, Mother was admitted into hospice care. She died with family and friends around her.

In the Legacy Project from which these cases were selected (Allen et al., in press), our patient-caregiver sample was primarily Black/African American, suggesting that interventions such as Legacy might be particularly appealing within that, and perhaps other, underserved group. Roff and colleagues (Roff et al., 2004) explored racial differences in positive aspects of caregiving (PAC) as reported by dementia caregivers. They observed higher levels of PAC in Black/African American caregivers than Whites/Caucasians. Moreover, religiosity mediated the relationship between PAC and race. Gaines (1988) suggests that goals related to emotional gratification may be most salient to Black/African American caregivers. Black/African American caregivers seek to reinforce positive qualities of relationships to enhance the basic family infrastructure. Thus, Black/African American caregivers may experience particular benefit from interventions such as the Legacy Project that focus on reinforcing positive reappraisal, affective connections, and role performance when dealing with caregiving difficulties (Knight & McCallum, 1998). In fact, the similarity between the Legacy intervention and the culture of transmitting knowledge through oral history within African American families may make recruitment of non-African American families into Legacy interventions somewhat challenging.

Not all families consist of individuals related by blood or marriage. The third case example from the Legacy Project illustrates the importance of friendship.

CASE 3

Ms. A and Ms. B were rural-dwelling African American life-long friends. Ms. A was the 70-year-old patient with 14 years of education. She was a widow and had never had children. Ms. B was 68-years-of-age and had 12 years of education. Both women reported their health as “fair” for their age.

The Caucasian interventionist working with this dyad attempted unsuccessfully to engage them in brainstorming multiple potential Legacy Projects. However, Ms. A had decided during her recruitment into the project that her Legacy would be a “Down Home Cookbook.” Themes identified during this session included individuality, spirituality and the importance of religion, overcoming adversity, generativity, and the centrality of friendship. During Session One Ms. A stated:

Ms. A: “This Legacy has been passed down through the years among our ancestors.”

Regarding what she would like others to remember about her (see Table 1) she stated:

Ms. A: “Me being myself. I am not a put on person…Trust in God should head the list.”

In response, Ms. B stated that she cherished “our friendship because [Ms. A] never changes. She’s the same every time you see her.” Ms. B also reiterated the centrality of faith in Ms. A’s life:

Ms. B: “I want to remember her spirituality, because she has always believed and trusted in God…and she just always been there for me. Been a friend to me. And we might not see each other every day or every week but we always knew that we could call each other and we would be there for each other. She has been a strength to me.”

During the course of the first intervention session, Ms. A talked about her concern that she had become a burden to Ms. B. In response, Ms. B reminded Ms. A of a time of crisis in her own past and what Ms. A had told her then. Next, Ms. B uttered perhaps the most notable quote of the Legacy Project:

Ms. B: “You told me, you said, ‘if you can’t go forward, don’t go backward. Stand still.’ And that meant a whole lot to me.”

In the third Legacy intervention session, Ms. A and Ms. B gave a copy of the Down Home Cookbook to their Legacy interventionist. Both were positive about their experiences in the Legacy Project.

Ms. A: “I’m very satisfied with it. It felt good to me because some of those things I haven’t really cooked in a long time and I have always loved to cook…it gives you something to do. It just brings back good memories...I think everybody should do it.”

Ms. B: “I liked it.”

The third case study from the Legacy Project illustrates how ill persons often worry that their illness is interfering with other responsibilities of their caregivers. Approximately 39% of patients with advanced cancer report mild concern from self-perceived burden to others while an additional 38% report moderate to extreme concern (McPherson, Wilson, & Murray, 2007; Wilson, Curran, & McPherson, 2005). Moreover, family caregivers of individuals approaching the end of life are at risk of stress, depression, and health problems (McMillan, 2005; McMillan et al., 2006). Thus, interventions targeting family relationships that balance the needs of all family members and facilitate growth in accordance with family values (Qualls, in press) have the potential to improve well-being and reduce feelings of being a burden and feelings of depression among patients while reducing the stress of family caregivers.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

As stated in our primary outcome paper (Allen et al., in press), initial data suggest that the three-session Legacy intervention holds promise as a treatment for individuals with chronic, life-limiting illnesses and their palliative family caregivers. These three case examples from the Legacy Project illustrate the diversity of dyads that may find the combination of mutual reminiscence and engagement in meaningful activity via Legacy creation beneficial. Patients near the end of life give great emphasis to family communication over and above symptom control (Perkins, Barclay, & Booth, 2007). In our initial project, Caucasians and African Americans, individuals living in urban and rural settings, and those with high and average levels of education responded positively to the intervention. For African Americans, interventions that specifically target positive family interactions may prove to be most beneficial (Gaines, 1988). Programs such as the Legacy Project that focus on improving communication skills among family members might be further developed for this group, with greater emphasis given to within-group variations in culture (Dilworth-Anderson, Goodwin, & Williams, 2004).

Results regarding the efficacy and acceptability of the Legacy intervention suggest that the combined treatment components of mutual reminiscence and engagement in pleasant events, targeting meaning-based coping (Folkman, 1997), may improve patients’ and caregivers’ communication and emotional aspects of quality of life. Enhancing family communication may facilitate patients’ generativity, the desire to give of oneself to future generations. Future research should investigate the potential of implementing the Legacy intervention through community volunteers to increase the likelihood of real-world translation, widespread implementation, and enhanced cost effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by funding from the National Institute on Aging (K01AG00943) to R. S. Allen and the Center for Mental Health and Aging, University of Alabama, via the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (1H79SM54569) to R. S Allen. Special thanks are extended to Michelle M. Hilgeman and Margaret A. Ege for excellent project management, to Louise Lewis and Kay Bostic for assistance in recruitment, to Andrew Helveston for transcribing audiotapes, to Forrest Scogin for reviewing audiotapes and coding treatment delivery, and to all of the patients and caregivers who gave generously of their time and energy to this project.

References

- Affleck G, Tennen H. Construing benefits from adversity: Adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:899–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Hilgeman MM. The Legacy Participant Notebook. 2003. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Hilgeman MM, Ege MA, Shuster JL, Jr, Burgio LD. Legacy activities as interventions approaching the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0294. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Shuster JL. The role of proxies in treatment decisions: Evaluating functional capacity to consent to end-of-life treatments within a family context. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2002;20:235–252. doi: 10.1002/bs1.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. A life-span approach to social motivation. In: Heckhausen J, Dweck C, editors. Motivation and self-regulation across the life span. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 341–364. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA, Mather M. Aging and the intersection of cognition, motivation, and emotion. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. 6. New York: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:310–324. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity Therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:5520–5525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity and psychotherapeutic considerations in end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Care. 2004;20(3):134–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Parpura-Gill A, Golander H. Utilization of self-identity roles for designing interventions for persons with dementia. Journal of Gerontology B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(B):202–212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW, Gallagher-Thompson D, Thompson L. interventions to reduce dementia caregiver distress: a clinical guide. New York: Springer; 2003. Innovative. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Goodwin P, Williams SW. Can culture help explain the physical health effects of caregiving over time among African American caregivers? Journal of Gerontology: Social Science. 2004;59:S138–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh RR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines AD. Alzheimer’s disease in the context of black (Southern) culture. Health Matrix. 1988;6(4):33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, de Leon CF, Bassuk SS, Berkman LF. Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: Longitudinal findings. Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:604–628. doi: 10.1177/0898264306291017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgeman MM, Allen RS, DeCoster J, Burgio LD. Positive aspects of caregiving as a moderator of treatment outcome over 12 months. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:361–371. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopko DR, Armento M, Chambers L, Cantu M, Lejuez CW. The use of daily diaries to assess the relations among mood state, overt behavior, and reward value of activities. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:1137–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(03)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, McCallum TJ. Heart rate reactivity and depression in African-American and white dementia caregivers: Reporting bias or positive coping? Aging & Mental Health. 1998;2(3):212–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. Positive and negative affective states among older people in long-term care. In: Rubinstein RL, Lawton MP, editors. Depression in Long Term and Residential Care: Advances in Research and Treatment. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Knight M. Goal-directed memory: The role of cognitive control in older adults’ emotional memory. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:554–570. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC. Interventions to facilitate family caregiving at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S132–S139. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Schonwetter R, et al. Impact of a coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2006;106:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson CJ, Wilson KG, Murray MA. Feeling like a burden to others: A systematic review focusing on the end of life. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21:115–128. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M, Carstensen LL. Age and emotional experience during mutual reminiscing. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:430–442. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins P, Barclay S, Booth S. What are patients’ priorities for palliative care research? Focus group study. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21:219–225. doi: 10.1177/0269216307077353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualls SH. Caregiver family therapy. In: Knight B, Laidlaw K, editors. Handbook of emotional disorders in older adults. Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- Roff LL, Burgio LD, Gitlin L, Nichols L, Chaplin W, Hardin JM. Positive aspects of Alzheimer’s caregiving: The role of race. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59:P185–P190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scogin F, Welsh D, Hanson A, Stump J, Coates A. Evidence-based psychotherapies for depression in older adults. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12(3):222–237. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano JP, Latorre JM, Gatz M, Montanes J. Life review therapy using autobiographical retrieval practice for older adults with depressive symptomatology. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:272–277. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G. Daily processes in coping with chronic pain: Methods and analytic strategies. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of coping. New York: John Wiley; 1996. pp. 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KG, Curran D, McPherson CJ. Burden to others: A common source ofdistress for the terminally ill. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;34:115–123. doi: 10.1080/16506070510008461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]