Abstract

Purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) is a rare occurrence, in which the patient has a purple-colored urine bag following urinary catheterization for hours to days. Most of authors believe it is a mixture of indigo (blue) and indirubin (red) that becomes purple. Previous study showed that PUBS occurred predominantly in chronically catheterized, constipated women. We collected 10 elderly patients with PUBS in two nursing homes. The first two cases were identified by chart review in 1987 and 2003, and then later eight cases (42.1%) were collected among 19 urinary catheterized elderly in the period between January 2007 and June 2007. In the present report, PUBS probably can occur in any patients with the right elements, namely urinary tract infection (UTI) with bacteria possessing these enzymes, diet with enough tryptophan, and being catheterized. Associations with bed-bound state, Alzheimer’s, or dementia from other causes are reflections of the state of such patients who are at higher risk for UTI, and hence PUBS occurred. Although we presented PUBS as a harmless problem, prevention and control of the nosocomial catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs) has become very important in the new patient-centered medical era. Thus, we should decrease the duration of catheterization, improve catheter care, and deploy technological advances designed for prevention, especially in the elderly cared for in nursing homes.

Keywords: purple urine bag syndrome, indigo, indirubin, nursing home, bacteriuria, indoxyl sulphatase/phosphatase, nosocomial catheter-associated UTIs

Introduction

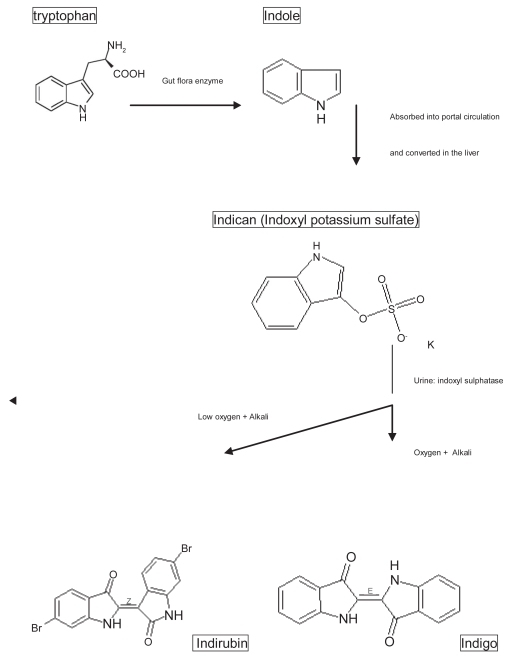

Purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) was first reported in 1978 (Barlow and Dickson 1978). The patient had a purple-colored urine bag following urinary catheterization for hours to days (Stott et al 1978; Dealler et al 1988; Al-Jubouri and Vardhan 2001; Lin et al 2002). Although the definite chemical substrate of PUBS is unknown, most authors believe it is a mixture of indigo (blue) and indirubin (red) that becomes purple (Dealler et al 1988; Matsuo et al 1993; Umeki 1993; Nakayama and Kanmatsuse 1997; Ishiha et al 1999; Al-Jubouri and Vardhan 2001; Ribeiro et al 2004). The chain reaction responsible for PUBS began with tryptophan from the food chain being metabolized by gut bacteria. This metabolic process produces indole, which is absorbed into portal circulation and converted to indoxyl sulphate in the liver, after a series of detoxification transformations (Figure 1) (Chiou et al 2005).

Figure 1.

The formation of indigo and indirubin from tryptophan in the gastrointestinal tracts.

Case report

In this study, we collected 10 elderly patients with PUBS cared for by the senior registered nurses at two nursing homes in southern Taiwan community hospitals (Table 1). Case 1 and case 2 who were identified by chart review in 1987 and 2003, respectively, and the latter 8 cases (3 males, 5 females) were collected between January 2007 and June 2007. The two nursing home had 74 residents (52 males, 22 females), of which 19 (8 males, 11 females) had undergone Foley catheterization. The incidence of PUBS was 42.1% among the 19 urinary catheterized nursing home residents in the follow-up half-year period.

Table 1.

Demographic data, diagnoses, medications, laboratory finding, duration of bedridden, and Foley catheterization in the ten cases

| Diagnosis | Age/sex | Medications | Urine PH | Urine culture | Constipation | B/R | Laboratory examination | Bedridden | Foley | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | DM# | 72/M | None | Nil* | Nil | (−) | Nil | Nil | 3 yrs | 36 m |

| DN with ESRD* | ||||||||||

| AD§ | ||||||||||

| Case 2 | DM | 72/M | None | Nil | Nil | (−) | Nil | Nil | 2 yrs | 24 m |

| DN with ESRD | ||||||||||

| AD | ||||||||||

| Case 3 | DM | 83/M | Norvasc | 8.0 | E.Coli | (−) | WBC 6600/Hb 9.3 | WNL◎ | 3 yrs | 26 m |

| AD | Proteus mirabilis | |||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| Case 4 | DM | 89/M | Lasix | 8.5 | E.Coli | (−) | WBC 6800/Hb 10.7 | BUN 30 | 5 yrs | 33 m |

| DN with ESRD BPH | Proteus mirabilis | Cr 2.5, Others WNL | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| Case 5 | VaD✯ | 80/M | Dexaben | 9.0 | Providencia rettgeri | (+) | WBC 6400/Hb 10.5 | WNL | 1.5 yrs | 12 m |

| Hypertension | Seroquel | |||||||||

| BPH▴ | Stilnox | |||||||||

| Case 6 | AD | 80/F | None | 9.0 | E.Coli | (−) | WBC 7200/Hb 11.4 | GOT 40 | 5 yrs | 24 m |

| Anemia | Chol 201 | |||||||||

| Pulmonary fibrosis | Glu 52 | |||||||||

| Hepatitis | ||||||||||

| Hypercholestrolemia | ||||||||||

| Case 7 | VaD | 76/F | None | 8.0 | Klebsiella Pneumoniae | (+) | WBC 6300/Hb 8.6 | WNL | 10 yrs | 72 m |

| Anemia | ||||||||||

| Case 8 | VaD | 66/F | Norvasc | 8.0 | Klebsiella Pneumoniae | (−) | WBC 3800/Hb 11.7 | GOT 94 | 4 yrs | 48 m |

| Hypertension | Deanxit | GPT 112 | ||||||||

| Hepatitis | Chol 222 | |||||||||

| Hypercholestrolemia | Others WNL | |||||||||

| Csae 9 | Schizophrenia | 60/F | Deanxit | 9.0 | Providencia | (−) | WBC 6900/Hb 11.7 | WNL | 5 yrs | 60 m |

| AD | Ativan | rettgeri | ||||||||

| Poliomyelitis | ||||||||||

| Case 10 | DM | 75/F | Minidiab | 8.0 | Klebsiella Pneumoniae | (+) | WBC 8300/Hb 14.1 | Glu 157 | 6 yrs | 24 m |

| VaD | Adalat | TG 463 | ||||||||

| Hypertension | Chol 221 | |||||||||

| Hypercholestrolemia |

Abbreviations: Nil, no data available;

WNL, within normal limit;

DM, diabetes mellitus; DN with ESRD, Diabetic nephropathy with end-stage renal disease;

AD, Alzheimer’s dementia;

VD, vascular dementia;

BPH, benign prostate hypertrophy.

Case 1, a 72-year-old male with PUBS, was found in 1987. He was a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), diabetic nephropathy (DN), and end-stage renal disease (ESRD), treated with hemodialysis for 3 years. He was lost to follow-up after being transferred to a medical hospital due to a medical illness in 1990. PUBS had been observed off and on for 3 years.

Case 2, a 72-year-old male, was a patient with type 2 DM, diabetic nephropathy, and ESRD, treated with hemodialysis. PUBS had persisted off and on for 3 years, beginning in November 2000. He expired because he refused hemodialysis in 2003. PUBS had been noted off and on for one year.

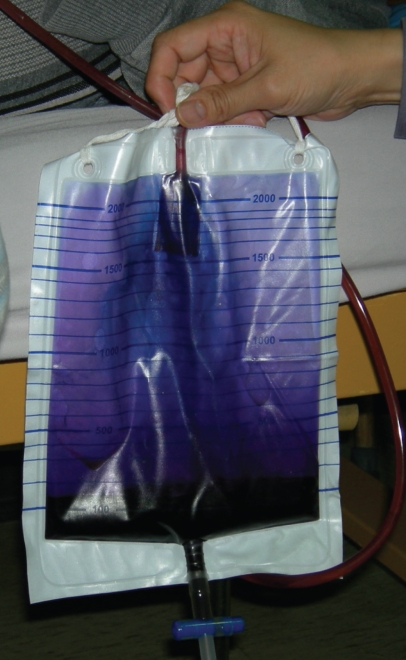

Case 3, an 83-year-old male, had had DM for about 15 years, Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) for 2 years, and hypertension treated with amlodipine besylate (Norvasc®) 5 mg per day for about 10 years. He had received Foley catheterization due to neurological bladder for more than 26 months. The patient had a purple-colored urine bag 2–3 days following urinary catheterization or changing of the Foley off and on for more than 24 months (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The urinary catheter drainage system with changing color from red to purple and sometimes with differently colored tube and bag in case 3 with purple urine bag syndrome.

Case 4, an 89-year-old male, had been a patient with DM and diabetic nephropathy for 40 years, ESRD treated with hemodialysis for 20 years, Alzheimer’s dementia for about 5 years, and hypertension treated with furosemide (Lasix®) 40 mg per day for 20 years. He underwent Foley catheterization due to benign prostate hypertrophy (BPH) and had suffered from PUBS off and on for more than 33 months, before being transferred to this nursing home (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The longer the PVC bag stayed in use for a patient, the deeper the color purple the bag became, despite changing sterile PVC urine bags from 2 different companies.

Case 5, an 80-year-old male, had been a patient with vascular dementia (VaD) with delirium since 2 years ago. He had also suffered from hypertension and BPH for 20 years. He became long-term bedridden because of fracture of the left femoral neck about 3 years ago. He suffered from PUBS off and on for 10 months. He regularly took doxazosin mesylate (Doxaben®) 1 mg per day for hypertension and BPH, and quetiapine fumarate (Seroquel®) 100 mg per day for vascular dementia with delirium.

Case 6, an 80-year-old female, was a patient with Alzheimer’s dementia, anemia, hepatitis, hypercholestrolemia and pulmonary fibrosis. She became long-term bedridden since 5 years ago. She suffered from PUBS off and on for 2 years. She did not take any drugs regularly.

Case 7, a 76-year-old female, had been a patient with VaD and anemia since 10 years ago. She had received Foley catheterization for 6 years. PUBS had been noted off and on for 2 years. She did not take any drugs.

Case 8, a 66-year-old female, was a patient with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and VaD with delirium. She took amlodipine besylate (Norvasc®) 10 mg per day for hypertension, and Melitracen 10 mg/Flupentixol 0.5 mg (Deanxit®) 1 tab per night for VaD with delirium. She became long-term bedridden and received Foley catheterization for 4 years after a stroke. PUBS had been noted off and on for 16 months.

Case 9, a 60-year-old female, was a patient with schizophrenia and poliomyelitis. She became long-term bedridden and received Foley catheterization for 5 years. PUBS had been noted off and on for 4 years. She regularly took Melitracen 10 mg/Flupentixol 0.5 mg (Deanxit®) 2 tab per night and lorazepam (Ativan®) 0.5 mg per night.

Case 10, a 75-year-old female, had been a patient with DM, hypertension, VaD, and hypercholestrolemia for 6 years. She had taken glipizide (Minidiab®) 5 mg per day for DM, and nifedipine (Adalat OROS®) 30 mg per day for hypertension. She had been long-term bedridden for 6 years after a stroke, and had received Foley catheterization for 1 year. PUBS had been noted for 3 months.

The mean age of the 10 elderly patients (5 males, 5 females) was 75.30 years (SD 8.39, range 60–89). They were long-term bedridden for an average of 4.45 years (SD 2.43, range 1.5–10), and received urinary catheterization for an average of 35.9 months (SD 18.66, range 12–72). Only about 30.0% of the patients had had long-term constipation. Their vital signs were all stable even though their urine routine showed urinary tract infection (UTI). Among the ten cases, 9 (90.0%) had dementia; 80% of the male cases also had diagnoses of DM, diabetic nephropathy, and ESRD with hemodialysis. Therefore PUBS had a higher incidence in patients with chronic disease such as dementia, diabetic nephropathy, a long-term bedridden state, and long-term Foley catheterization.

The later 8 cases received further laboratory examinations. They had purple, crystalline, and alkaline urine (PH 8.0~9.0). Escherichia coli, Klebsiella Pneumoniae, Providencia rettegeri, and Proteus mirabilis were revealed in their urine culture. Their blood routine showed white blood cells, 3800~8300/μL, and Hb, 8.6~14.1 g/dL. Seven cases (87.5%) had mild anemia. In the biochemistry examinations, seven cases (87.5%) revealed normal renal functioning, except case 4 with diabetic nephropathy with ESRD. Three cases (37.5%) had hypercholestrolemia. Two cases (25%) had hepatitis. All patients had stable vital signs, and had no infection sign such as leukocytosis, fever, or chill was found, even though PUBS and bacteriuria persisted. All patients did not receive any antibiotics treatment. We decreased their duration of catheterization, replaced their Foley and urine bag regularly, and improved their quality of catheter care. Then PUBS did not occur again.

Discussion

PUBS is rarely reported: only one larger survey study among the 23 papers regarding PUBS published since 1987 was found in a PubMed search. Although the exact prevalence of PUBS is unknown, but it may not be rare because the prevalence of PUBS was found to be 9.8% (seven of 71) in the study of Dealler and colleagues (1988) and 8.3% (13 of 157) at a long-term care service center in a Taiwan community hospital (Su et al 2005). In this report, the prevalence of PUBS was as high as 42.1% (eight of 19) in urinary catheterized nursing home residents. Why the prevalence of PUBS was so high in this report? We need a larger study for further evaluation of PUBS in Taiwan nursing home in the future.

A previous study showed that PUBS occurred predominantly in chronically catheterized, constipated women (Su et al 2005). No previous positive association study between PUBS and medications, such as Norvasc®, Lasix®, Doxaben®, Adalat OROS®, Minidiab®, Seroquel®, Deanxit®, or Stilnox® has been reported before. PUBS was found to be associated with alkaline urine as well as UTI induced by some species of bacteria with indoxyl sulphatase/phosphatase (Ribeiro et al 2004). But in this report, the four cases at the first nursing home were all male and were nursing home residents since 1987. They also did not have long-term constipation or diarrhea. Female gender or constipation was possibly not the absolute criteria of PUBS. This is similar to the viewpoint of Lin and colleagues (2002).

In urine culture, several bacterial species have been reported in association with PUBS including Providencia stuartii, P. rettgeri, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, E. coli, Morganella morganii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Dealler et al 1988; Matsuo et al 1993; Umeki 1993; Nobukuni et al 1995; Ishiha et al 1999; Al-Jubouri et al 2001; Lin et al 2002; Zotti et al 2004). Our urine culture results were similar to those of previous reports, and revealing E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. rettegeri, and P. mirabilis.

P. mirabilis compromises the care of many patients undergoing long-term indwelling bladder catheterization. In a prevalence study of hospital-acquired infections (HAI), a significant correlation was found with major risk factors related to medical procedures, such as urinary catheterization (Zotti et al 2004). A failure to decrease the unnecessary bladder catheter use and the duration of catheterization would result in poor quality of care (Landi et al 2004), a greater mean length of stay in hospital, and a higher risk of nosocomial UTI (Zotti et al 2004).

It was apparent that PUBS affected not only the urine bags but also indwelling catheters. The urinary catheter drainage system changed color from red to purple and sometimes showed differently colored tubes and bags, as in case 3 with PUBS (Figure 2). We found that the longer the PVC bag stayed in use for a patient, the deeper the color purple the bag became, despite changing sterile PVC urine bags from 2 different companies, which was compatible with the findings of Dealler and colleagues (1988) and Su and colleagues (2005).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the pigments associated with PUBS have been well shown to be due to indirubin and indigo. The pathogenesis of PUBS is due to the metabolism of tryptophan by bacteria to indole and later converted to indicant in the liver (Dealler et al 1988). This is excreted and in the urine broken down by bacteria possessing one or both enzymes, sulphatase and phosphatase that metabolize this pigment to indirubin and indigo in an alkaline environment (urine). The indigo can also be precipitate in the catheter itself giving a blue discoloration (Harun et al 2007). In this paper, we found that PUBS seemed to have a higher incidence in patients with a bedridden status, alkaline urine, and species of bacteria with indoxyl sulphatase/phosphatase, but possibly not associated with gender, constipation, or type of PVC urine bag used. We also presented that PUBS was a harmless, but alarming problem (Robinson 2003). It is unnecessary to aggressively treat patients with PUBS, but the control of urological sanitation is fundamental to treatment.

In Taiwan, geriatric medicine, nursing home care, and HAI control have become very important because nosocomial catheter-associated UTIs comprise a huge silent reservoir of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and yeasts (Tambyah and Maki 2000; Robinson 2003; Hampton 2004). Thus, we should decrease the duration of catheterization, improve catheter care, and deploy technological advances designed for prevention.

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful for the psychiatric network support of Tsuey-Jen Fun of the subsidiary nursing home of Lin-Hie General Hospital, and Yuan-Huei Chou of the private Fu-Hua Rest Home. We also deeply appreciate the help of Shu-Li Huang and Shion-Ling Shyu of the psychiatric home visit team in Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Al-Jubouri MA, Vardhan MS. A case of purple urine bag syndrome associated with Providencia rettgeri. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:412. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.5.412-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow GB, Dickson JAS. Purple urine bags. Lancet. 1978;28:220–1. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou YK, Yiang GT, Wang CH, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome – a case report. Tzu Chi Med J. 2005;17:279–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dealler SF, Hawkey PM, Millar MR. Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia stuartii and Klebsiella pneumoniae causes the purple urine bag syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2152–6. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2152-2156.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton S. Nursing management of urinary tract infections for catheterized patients. Br J Nurs. 2004;13:1180–4. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2004.13.20.17007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harun NS, Nainar SK, Chong VH. Purple urine bag syndrome: a rare and interesting phenomenon. South Med J. 2007;100:1048–50. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318151fba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiha T, Ogura S, Kawakami Y. Five cases of purple urine bag syndrome in a geriatric ward. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 1999;36:826–9. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.36.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi F, Cesari M, Onder G, et al. Indwelling urethral catheter and mortality in frail elderly women living in community. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:697–701. doi: 10.1002/nau.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HH, Li SJ, Su KB, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Intern Med Taiwan. 2002;13:209–12. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo H, Ishibashi T, Araki C, et al. Report of three cases of purple urine bag syndrome which occurred with a combination of both E. coli and M. morgnii. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1993;67:487–90. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.67.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T, Kanmatsuse K. Serum levels of amino acid in patients with purple urine bag syndrome. Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1997;39:470–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobukuni K, Kawahara S, Nagare H, et al. Study on purple pigmentation in five cases with purple urine bag syndrome. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1995;69:1269–71. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.69.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JP, Marcelino P, Marum S, et al. Case report: Purple urine bag syndrome. Crit Care. 2004;8:R137. doi: 10.1186/cc2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. Purple urinary bag syndrome: a harmless but alarming problem. Br J Community Nurs. 2003;8:263–6. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2003.8.6.11547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott A, Khan M, Roberts C, et al. Purple urine bag syndrome. Ann Clin Biochem. 1978;24:185–8. doi: 10.1177/000456328702400212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su FH, Chung SY, Chen MH, et al. Case analysis of purple urine-bag syndrome at a long-term care service in a community hospital. Chang Gung Med J. 2005;28:636–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambyah PA, Maki DG. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection is rarely symptomatic: a prospective study of 1497 catheterized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:678–82. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeki S. Purple urine bag syndrome associated with strong alkaline urine. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1993;67:1172–7. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.67.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotti CM, Messori Ioli G, Charrier L, et al. Hospital-acquired infections in Italy: a region wide prevalence study. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56:142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]