Abstract

Context: Leptin deficiency is associated with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance in animals and humans with lipoatrophy; leptin replacement ameliorates these abnormalities.

Objective: The objective of the study was to evaluate the effects of leptin therapy in lipoatrophic HIV-infected patients with dyslipidemia and hypoleptinemia.

Design: This was a 6-month, open-label, proof-of-principle pilot study.

Setting: Metabolic ward studies were performed before and 3 and 6 months after leptin treatment.

Participants: Participants included eight HIV-infected men with lipoatrophy, fasting triglycerides greater than 300 mg/dl, and serum leptin less than 3 ng/ml.

Intervention: Recombinant human leptin was given by sc injection (0.01 mg/kg and 0.03 mg/kg twice daily for successive 3 month periods).

Outcome Measures: Measures included fat distribution by magnetic resonance imaging and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; fasting lipids; insulin sensitivity by euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp; endogenous glucose production, gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and whole-body lipolysis by stable isotope tracer studies; oral glucose tolerance testing; liver fat by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy; and safety.

Results: Visceral fat decreased by 32% (P = 0.001) with no changes in peripheral fat. There were significant decreases in fasting total (15%, P = 0.012), direct low-density lipoprotein (20%, P = 0.002), and non-high-density lipoprotein (19%, P = 0.005) cholesterol. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol increased. Triglycerides, whole-body lipolysis, and free fatty acids decreased during fasting and hyperinsulinemia. Fasting insulin decreased. Endogenous glucose production decreased during fasting and hyperinsulinemia, providing evidence of improved hepatic insulin sensitivity. Leptin was well tolerated but decreased lean mass.

Conclusions: Leptin treatment was associated with marked improvement in dyslipidemia. Hepatic insulin sensitivity improved and lipolysis decreased. Visceral fat decreased with no exacerbation of peripheral lipoatrophy. Results from this pilot study suggest that leptin warrants further study in patients with HIV-associated lipoatrophy.

Leptin treatment improves lipids and hepatic insulin sensitivity and decreases visceral fat and thus may have therapeutic potential in patients with HIV-associated lipoatrophy and hypoleptinemia.

HIV-associated metabolic and morphologic alterations, including dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, lipoatrophy, and central fat accumulation, are recognized increasingly as a major complication of otherwise effective highly active antiretroviral therapy. Because this cluster of metabolic abnormalities, commonly referred to as HIV lipodystrophy, is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease in non HIV-infected populations, it is now feared that lipodystrophy may impact the long-term prognosis in HIV-infected patients whose life expectancies have been significantly extended due to effective viral suppression by highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Whereas the association of dyslipidemia and insulin resistance with obesity is well recognized, more recent studies have demonstrated that fat loss (lipoatrophy) can result in similar metabolic abnormalities. In transgenic mice engineered to have virtually no white fat, a severe metabolic syndrome develops, characterized by insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridemia, hepatic steatosis, and decreased levels of adipocyte-derived hormones such as leptin and adiponectin (1,2). Evidence that the lack of fat is responsible for the phenotype is provided by experiments in which transplantation of fat from wild-type mice ameliorated these metabolic abnormalities (3). Both HIV-infected (4,5) and uninfected (6,7) humans with lipoatrophy manifest a similar metabolic profile, including hypoleptinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hyperinsulinemia.

Treatment with recombinant methionyl human leptin ameliorated these metabolic abnormalities in both fatless mice (8,9) and humans with lipoatrophy (10,11,12). Prompted by these findings, we undertook an open-label, proof-of-principle, dose-ranging study to comprehensively assess the metabolic and morphologic effects of recombinant human leptin treatment of HIV-infected subjects with lipoatrophy and hypoleptinemia.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects and study protocol

Medically stable HIV-infected men with clinical evidence of lipoatrophy, hypoleptinemia (serum leptin <3.0 ng/ml), and hypertriglyceridemia (fasting triglyceride levels ≥300 but <1000 mg/dl; or, if on hypolipidemic therapy, documentation of prior triglyceride ≥300 mg/dl) were recruited for study. These eligibility criteria were based on those used in a trial of leptin therapy in non HIV-infected patients with congenital or acquired lipodystrophy (10). Subjects who were on hypolipidemic therapy at baseline were required to have been on stable treatment for at least 3 months. Other eligibility criteria included demonstration of normal adrenal and thyroid function by measurement of fasting serum cortisol and TSH levels and dexamethasone suppression testing. Of 70 individuals with lipoatrophy who underwent screening, 13 met all of these eligibility criteria and eight enrolled. The primary reasons for screen failures were leptin greater than 3 ng/ml (71%) and triglycerides less than 300 mg/dl (52%). The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Before treatment, subjects were hospitalized in the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at San Francisco General Hospital Medical Center for 5 d to undergo comprehensive studies of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Body fat content and distribution were also assessed. After this initial evaluation, treatment with recombinant methionyl human leptin (Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA) was begun. For the initial 3 months, leptin was administered at a dose of 0.01 mg/kg twice daily, a dose that was expected to increase plasma leptin levels to the low-normal range.

After 3 months, the subjects were readmitted to the GCRC for a repeat 5-d metabolic evaluation, and the dose was then increased to 0.03 mg/kg twice daily. This latter dose was expected to achieve plasma leptin levels in the high-normal range. After 6 months of treatment, subjects were readmitted to the GCRC for a repeat of all of the studies that were performed at baseline and 3 months. Subjects also reported to the GCRC at months 1, 2, 4, and 5 for outpatient assessments that included collection of fasting blood samples, measurement of weight, an updated medical history, and safety assessment.

Inpatient studies

During each admission, subjects were fed a fixed diet. Energy intake was set at a level to maintain weight; the diets provided a protein intake of 1.5 g/kg · d or greater and carbohydrate intake of 40–50% of total energy content. Subjects were asked to prepare written food intake diaries for 3–7 d before each inpatient admission, and energy and macronutrient intake was analyzed using Food Processor software (version 7.0, ESHA Research, Salem, OR).

Body composition

Height was measured using a stadiometer. Subjects were weighed under fasting conditions on a calibrated scale. Visceral (VAT) and sc (SAT) abdominal adipose tissue areas at L4-L5 and midthigh cross-sectional muscle and sc fat area were measured by wide-slice magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; Magnetom 1.5T clinical MRI system; Siemens, Malvern, PA) and analyzed using a customized software program written in the interactive data language platform (IDL Research Systems, Inc., Boulder, CO). Fat and lean body mass (LBM) were measured by whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA; Lunar model DPX, Madison, WI) with regional analysis as described previously (13).

Intrahepatic lipid content was measured in the right lobe of the liver by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the aforementioned 1.5T magnet with a loop surface coil and using an image-guided localized proton spectra with a voxel size of approximately 30 cm3. Volume-selective shimming was performed and spectra were recorded by a STEAM technique (repetition time = 3000 msec, echo time = 15 msec, acquisitions 256, averages 1) with and without frequency-selective water suppression. The recorded signals were analyzed using J-MRUI fitting software (14). Chemical shifts were measured relative to water signal intensity at 4.8 ppm. Methylene signal intensity, which represents intracellular triglycerides in the liver (15), was assigned at 1.3–1.5 ppm.

Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity

On d 3 of the inpatient study, an oral glucose tolerance test was performed after an overnight fast and consumption of a minimum of 100 g carbohydrate per day during the previous 3 d. After collection of fasting blood samples, subjects drank a solution containing 75 g glucose in 300 ml. Blood samples were collected at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min after ingestion of the glucose solution for determination of plasma glucose and serum insulin levels. Integrated areas under the curve (AUCs) for glucose and insulin were calculated by the trapezoidal method.

Whole-body insulin sensitivity was measured on d 5 by the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp technique (16). After the baseline measurements were completed, insulin (Humulin; Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN), bound to human albumin, was infused at a rate of 40 mU/m2 · min for 180 min. Blood samples were collected at 5-min intervals from a retrograde iv line placed in a hand that was warmed in a heated box at 50–55 C. Whole-blood glucose concentrations were determined by the glucose oxidase method (Stat glucose analyzer; Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). A variable infusion of 20% dextrose (labeled with [U-13C] glucose) was adjusted to maintain plasma glucose concentrations at the baseline level. Blood samples were collected at 30-min intervals and the serum was frozen and batched for measurement of insulin. Insulin sensitivity was calculated as a measure of whole-body glucose uptake during the final hour of the clamp and adjusted for endogenous glucose production, steady-state serum insulin levels, and LBM (17).

Stable isotope tracer studies

Endogenous glucose production, gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and whole-body lipolysis were measured under conditions of fasting and hyperinsulinemia (during the clamp) by stable isotope infusion. On the evening of d 4, catheters were placed in the antecubital or forearm veins of each arm for infusion of the isotope solutions and periodic blood sampling. At 0430 h the following day, primed, continuous infusions of [U-13C] glucose (1.2 mg/kg · h), and [2-13C] glycerol (15 mg/kg LBM per hour) were begun. Steady-state blood sampling was performed between 0800 and 0830 h (fasting measurements) and during the final 30 min of the clamp (hyperinsulinemia). Endogenous glucose production (Ra glucose) and lipolysis (Ra glycerol) were calculated using standard dilution techniques (18). Gluconeogenesis was calculated using mass isotopomer distribution analysis (19,20). Glycogenolysis was calculated by subtracting the rate of gluconeogenesis from that of glucose production.

Indirect calorimetry

Oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were measured under fasting conditions and during the clamp by indirect calorimetry (DeltaTrac metabolic cart; SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA). Resting energy expenditure and substrate oxidation rates were calculated using stoichiometrically derived equations (21).

Laboratory assessments

Fasting blood samples were collected at 0800 h on d 4 for measurement of total, direct low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations, serum leptin levels, CD4 lymphocyte counts, and HIV RNA levels. Triglyceride and free fatty acid (FFA) concentrations were measured on d 5 under fasting and hyperinsulinemic (clamp) conditions. Postprandial triglyceride levels were also measured at 1900 h on d 5, after subjects had consumed a standardized lunch at 1200 h (upon conclusion of the clamp) and snack at 1500 h.

Laboratory assays

Triglycerides and total cholesterol were measured using Thermo Infinity reagents and HDL-C using the Thermo Trace/DMA HDL Precipitating kit (Thermo Electron, Melbourne, Australia). Direct LDL-C was measured using the Wako L-Type LDL-C reagents and FFA using the Wako NEFA kit (Wako Chemical USA, Richmond, VA). Serum insulin and leptin levels were measured by RIA (Linco Research Inc., St. Charles, MO) in the Core Hormone Laboratory of the GCRC at San Francisco General Hospital. CD-4 T cell counts were measured by flow cytometry, in the clinical laboratory at San Francisco General Hospital. HIV-1 RNA levels were quantified using the Amplicor HIV-1 monitor test (detection limit <75 copies/ml; Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ).

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means ± sem unless otherwise noted. For normally distributed data, results from pretreatment, month 3, and month 6 assessments were analyzed by one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Holm-Sidak pairwise multiple comparisons for significance of differences between time points. Nonnormally distributed data were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks with multiple comparisons by Tukey test. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat version 3.5 (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA). A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics and clinical course

Total body fat was less than 20% in six subjects and less than 10% in two (Table 1). Values for leg fat in all eight subjects were below the threshold for the lowest decile for seronegative controls in a large survey (22), providing objective evidence of peripheral lipoatrophy. By design, all subjects had fasting serum leptin levels less than 3 ng/ml, and the majority were less than 2. All subjects had stable CD4 cell counts at baseline. Seven subjects were on thymidine analog nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (stavudine or zidovudine). Seven subjects were also on lipid-lowering agents, and five were on testosterone replacement. Subject 8 had developed type 2 diabetes while on antiretroviral therapy before enrollment and was on rosiglitazone (8 mg daily). The respective doses and regimens of antiretroviral therapy, lipid-lowering agents, testosterone, and rosiglitazone remained unchanged throughout the study. All subjects tolerated the study procedures, were fully adherent to twice-daily injections, and completed the 6-month trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects

| Subject | Age (yr) | BMI (kg/m2) | Total fata (%) | Leg fata (kg) | Leptin (ng/ml) | CD4 (cells/μl) | ART regimen | Hypolipidemic Rx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42 | 24.1 | 12.4 | 1.24 | 1.2 | 438 | d4T, ABC, NVP, NFV | None |

| 2 | 51 | 21.4 | 6.9 | 0.77 | 1.6 | 758 | d4T, ddI, ABC, NVP | Atorvastatin 20 qd, Fenofibrate 160 qd |

| 3 | 47 | 23.4 | 20.4 | 2.73 | 2.1 | 230 | d4T, TDF, EFV, LPV/r | Atorvastatin 20 qd, Gemfibrozil 600 qd |

| 4 | 59 | 26.1 | 21.6 | 3.03 | 2.2 | 401 | AZT, 3TC, NVP | Gemfibrozil 600 bid |

| 5 | 48 | 22.0 | 12.2 | 1.73 | 1.6 | 372 | ABC, EFV, APV, T20 | Fenofibrate 160 qd |

| 6 | 62 | 24.0 | 7.5 | 1.48 | 1.1 | 1025 | d4T, 3TC, ABC, TDF, EFV | Ezetimibe 10 mg qd |

| 7 | 47 | 28.5 | 17.1 | 1.93 | 1.2 | 555 | d4T, ddI, EFV | Atorvastatin 10 qd |

| 8b | 59 | 24.3 | 14.5 | 1.50 | 1.6 | 478 | AZT, 3TC, ABC, NVP | Atorvastatin 40 qd |

ART, Antiretroviral therapy; 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; APV, amprenavir; AZT, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; ddI, didanosine; EFV, efavirenz; LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir; NFV, nelfinavir; NVP, nevirapine; TDF, tenofovir; T20, enfuvirtide; BMI, body mass index; bid, twice a day; qd, every day; Rx, treatment.

Total and leg fat measured by DEXA.

Subject 8 had type 2 diabetes and was on rosiglitazone at baseline and throughout the study.

Serum leptin levels

Serum leptin levels, measured 8–10 h after the preceding dose of leptin, increased in a dose-dependent manner, with mean values of 2.7 ± 0.6, 7.7 ± 1.9, and 21.3 ± 5.3 ng/ml at baseline and months 3 and 6, respectively (P = 0.002).

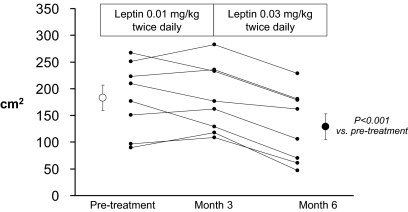

Effects of leptin on body composition

VAT decreased in all subjects (Fig. 1). The average decrease in VAT at month 6 was 32% (P = 0.001). A more variable effect on abdominal SAT was noted, with an overall change that was not significant (Table 2). An average weight loss of nearly 2 kg was largely attributable to decreases in LBM and trunk fat as measured by DEXA (Table 2). Thigh muscle cross-sectional area tended to decrease, consistent with the decreases in LBM by DEXA. Notably, neither limb (arm + leg) fat measured by DEXA nor thigh SAT measured by MRI decreased during treatment with leptin. Liver fat tended to decrease, but the change was not statistically significant. Two subjects had very low levels of liver fat at baseline (<2%), which left little margin for further reductions.

Figure 1.

VAT measured by MRI at L4–L5 before and after 3 and 6 months of leptin administration. Individual results and group mean ± sem are shown. Overall, VAT decreased by an average of 32% (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Effects of leptin on body composition

| Pretreatment | Month 3 | Month 6 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 74.6 ± 1.9 | 75.0 ± 2.3 | 72.7 ± 2.5a | 0.026 |

| MRI | ||||

| VAT (cm2) | 183 ± 24 | 181 ± 23 | 129 ± 24a,b | <0.001 |

| Abdominal SAT (cm2) | 102 ± 29 | 96 ± 24 | 88 ± 19 | 0.645 |

| Thigh muscle CSA (cm2)c | 78.1 ± 3.0 | 77.5 ± 3.1 | 75.5 ± 2.8 | 0.357 |

| Thigh SAT (cm2)c | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 0.418 |

| DEXA | ||||

| Lean body mass (kg) | 61.0 ± 1.8 | 61.1 ± 1.8 | 59.5 ± 1.9 | 0.065 |

| Total fat (kg) | 10.5 ± 1.5 | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 10.4 ± 1.4 | 0.663 |

| Trunk fat (kg) | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | 6.6 ± 1.0 | 0.226 |

| Limb fat (kg) | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 0.108 |

| Trunk to limb fat ratiod | 2.62 (2.03, 3.62) | 2.30 (1.98, 3.10) | 2.05b (1.83, 2.89) | 0.002 |

| MRS | ||||

| Intrahepatic triglyceride (%)c | 8.7 ± 2.6 | 9.6 ± 2.9 | 5.8 ± 2.0 | 0.256 |

Values in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.005). Data are mean ± sem and P values by repeated-measures ANOVA unless otherwise noted. VAT and SAT at L4-L5 and thigh SAT and muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) are by MRI. Total and regional fat and lean body mass were measured by DEXA. Limb fat is the sum of arm and leg fat. Intrahepatic triglycerides were measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

P < 0.05 vs. month 3 value.

P < 0.05 vs. pretreatment value.

n = 7 at each time point.

Median (Q1, Q3); analysis by repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks.

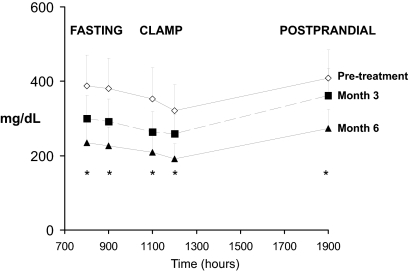

Effects of leptin on lipid metabolism

Total cholesterol, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C levels decreased significantly, with mean decreases of 15, 20, and 19% respectively, by month 6 (Table 3). HDL-C increased in six of eight subjects, with an average increase of 23%. Triglyceride levels decreased significantly under fasting, hyperinsulinemic (clamp), and postprandial conditions (Fig. 2). Whole-body lipolysis decreased under both fasting and hyperinsulinemic conditions, and the ability of insulin to suppress lipolysis increased with leptin (Table 3). Similarly, fasting FFA levels tended to decrease with leptin, and the ability of insulin to suppress FFA increased significantly.

Table 3.

Effects of leptin on lipid and glucose metabolism

| Pretreatment | Month 3 | Month 6 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting cholesterol | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 227 ± 19 | 200 ± 13a | 190 ± 12a | 0.012 |

| LDL-C (direct; mg/dl) | 142 ± 10 | 132 ± 7 | 113 ± 6a,b | 0.002 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dl) | 203 ± 18 | 173 ± 13 | 162 ± 11a,b | 0.005 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 24 ± 3 | 26 ± 2 | 28 ± 3a | 0.048 |

| Total to HDL cholesterol ratio | 10.8 ± 1.9 | 8.2 ± 1.1a | 7.7 ± 1.4a | 0.001 |

| Fasting triglycerides (mg/dl) | 387 ± 83 | 300 ± 62 | 235 ± 54a | 0.017 |

| Lipolysis (Ra glycerol; mg/kg · min) | ||||

| Fasting | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02a | 0.033 |

| Hyperinsulinemia (clamp) | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.02a | 0.10 ± 0.03a | <0.001 |

| Suppression by insulin | 16% | 39% | 35% | |

| Free fatty acid concentrations (mEq/liter ×1000) | ||||

| Fasting | 328 ± 59 | 308 ± 63 | 211 ± 48 | 0.133 |

| Hyperinsulinemia (clamp) | 125 ± 38 | 84 ± 21 | 60 ± 21a | 0.032 |

| Suppression by insulin | 65% | 70% | 76% | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 106 ± 6 | 107 ± 7 | 104 ± 5 | 0.546 |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/ml) | 21 ± 3 | 16 ± 1a | 16 ± 2a | 0.023 |

| 120-min glucose (mg/dl) | 137 ± 25 | 145 ± 24 | 145 ± 25 | 0.744 |

| 120-min insulin (μIU/ml) | 127 ± 42 | 87 ± 30 | 73 ± 19 | 0.161 |

| Glucose 3-h AUC | 383 ± 29 | 399 ± 30 | 379 ± 24 | 0.393 |

| Insulin 3-h AUC | 325 ± 73 | 262 ± 41 | 206 ± 32a | 0.046 |

| Insulin sensitivityc (mg/kg LBM per min/μIU · ml) | 5.64 (3.06, 8.65) | 4.95 (3.65, 7.49) | 7.82 (4.85, 10.05) | 0.285 |

| Endogenous glucose production (Ra glucose; mg/kg · min) | ||||

| Fasting | 2.78 ± 0.17 | 2.59 ± 0.33 | 2.47 ± 0.18a | 0.020 |

| Hyperinsulinemia (clamp) | 1.42 ± 0.20 | 0.76 ± 0.14a | 0.76 ± 0.14a | 0.003 |

| Suppression by insulin | 49% | 70% | 69% | |

| Gluconeogenesis (mg/kg · min) | ||||

| Fasting | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.269 |

| Hyperinsulinemia (clamp) | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02a | 0.025 |

| Suppression by insulin | 72% | 85% | 87% | |

| Glycogenolysis (mg/kg · min) | ||||

| Fasting | 2.15 ± 0.07 | 1.96 ± 0.12 | 1.89 ± 0.06 | 0.073 |

| Hyperinsulinemia (clamp) | 1.23 ± 0.19 | 0.67 ± 0.13 | 0.68 ± 0.07 | 0.005 |

| Suppression by insulin | 43% | 65% | 64% |

Values in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.05). Data are mean ± sem for normally distributed data; P values are by repeated-measures ANOVA unless otherwise noted.

P < 0.05 vs. pretreatment.

P < 0.05 vs. month 3.

Median (Q1, Q3); P value by repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks.

Figure 2.

Triglyceride levels measured under fasting conditions (800 and 900 h), during a euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp (1100 and 1200 h), and after feeding (1900 h) on d 5 of the inpatient studies. Data are mean ± sem. Pretreatment data are shown by open diamonds, month 3 data by filled squares, and month 6 data by filled triangles. *, Changes at each time point were statistically significant (P < 0.05; repeated measures ANOVA).

Effects of leptin on glucose metabolism

Although fasting glucose levels did not change during leptin treatment, fasting insulin concentrations decreased significantly (Table 3). Glucose levels measured 2 h after an oral glucose load did not change significantly with leptin, and 2-h insulin levels tended to decrease. Using the current classification system (23), two of the seven nondiabetic subjects had impaired fasting glucose both before and after 6 months of leptin treatment. Three of the seven nondiabetic subjects had impaired glucose tolerance during the pretreatment oral glucose tolerance test, which normalized after 6 months of leptin. Fasting and 2-h glucose levels in the subject with diabetes who was on stable rosiglitazone treatment met the criteria for diabetes both before and after leptin treatment. Although there was no significant change in glucose AUC in response to leptin treatment, insulin AUC decreased by approximately 30% (P = 0.046). Insulin-mediated glucose uptake tended to increase, but results were not consistent among subjects and failed to achieve statistical significance.

When measured under fasting conditions, endogenous glucose production decreased significantly during leptin treatment, an effect that can be attributed primarily to a reduction in glycogenolysis (Table 3). During the clamp, leptin treatment improved the ability of insulin to suppress endogenous glucose production, with significant decreases in both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.

Energy expenditure and intake

There were no significant changes in resting energy expenditure, adjusted for LBM, or lipid or carbohydrate oxidation rates under fasting and hyperinsulinemic conditions during the study (data not shown). Likewise, self-reported energy intake did not change significantly.

Safety and tolerability

Leptin treatment was well tolerated by all subjects. No clinical or laboratory adverse events were reported, including no changes in serum liver enzymes or hematology (Table 4). There were no injection site reactions or discomfort, or reports of headache or other somatic complaints that had been reported in other studies of leptin (10,24). CD4 T cell counts and viral loads remained stable in all subjects. HIV RNA levels were undetectable in six of the eight subjects at both baseline and month 6. Two subjects had detectable viremia at both baseline and month 6; of these, one experienced a 0.3 log increase and the other a 0.05 log decrease during treatment.

Table 4.

Safety measures

| Pretreatment | Month 3 | Month 6 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV RNA less than 75 copies/ml (n) | 6/8 | N/A | 6/8 | |

| CD4 count (cells/μl) | 458 (417, 617) | 442 (410, 580) | 460 (355, 510) | 0.999 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 14.2 (13.3, 14.7) | 14.2 (13.7, 15.0) | 14.0 (13.1, 16.1) | 0.531 |

| ALT (U/liter) | 36 (26, 53) | 31 (24, 44) | 27 (22, 43) | 0.236 |

| AST (U/liter) | 27 (22, 46) | 26 (24, 36) | 25 (22, 33) | 0.531 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 18 (15, 21) | 17 (13, 18) | 17 (14, 21) | 0.794 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 0.794 |

Data are median (Q1, Q3); P values by repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks. ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; N/A, not assessed.

Discussion

In this open-label pilot study in HIV-infected men with lipoatrophy and hypoleptinemia, administration of recombinant human leptin for 6 months was associated with a robust decrease in visceral fat, an increase in hepatic insulin sensitivity, and marked improvement of dyslipidemia. The decrease in VAT with leptin treatment was accompanied by a nonsignificant (14%; P = 0.645) decrease in abdominal SAT area, but neither peripheral (arm + leg) fat measured by DEXA or thigh SAT measured by MRI decreased. Although evidence of central fat accumulation was not an eligibility criterion in the current study, average values for VAT at baseline were comparable with those seen in studies of experimental treatments in HIV-infected patients selected for the presence of excess central fat. The mean decrease of 32% in VAT induced by leptin administration in this study exceeds decreases reported with other therapies. For example, administration of pharmacologic doses of GH decreased VAT by 21–24% in two randomized trials in subjects with abdominal obesity (25,26). However, pharmacological GH treatment is associated with impairment of glucose metabolism and exacerbation of insulin resistance (25,26,27,28) and loss of sc fat (25,26) and thus is not an optimal therapy in a population already predisposed to insulin resistance and lipoatrophy. A recent randomized trial of a synthetic GHRH, TH9507, reported a more modest reduction in VAT (15% in subjects who received active therapy) with no significant effect on glucose metabolism (29). In contrast, leptin improved glucose metabolism. Randomized trials of rosiglitazone in patients with HIV infection improved insulin sensitivity but consistently failed to reduce VAT (30,31,32), whereas those of metformin have shown modest, if any, reductions in VAT (31,32,33,34). Results of the current study will need to be confirmed in larger, placebo-controlled studies to determine whether leptin offers advantages over other potential treatments for HIV-associated abdominal fat accumulation.

The proportional loss of VAT relative to loss of fat or body weight in the current study is greater than has been observed in studies of individuals losing weight by simple caloric restriction, pharmacological weight loss therapy, or exercise (35). However, our subjects entered the study with relatively depleted stores of SAT, so we cannot determine whether their loss of VAT was selective or reflected its relative excess compared with SAT at baseline. Barzilai et al. (36) found a preferential loss of fat in intraabdominal depots in healthy rats that lost weight during leptin treatment when compared with pair-fed controls with the same rate of weight loss, and they speculated that the selective effect of leptin on VAT may be mediated through β-adrenergic stimulation. However, because loss of VAT in both the current study and that of Barzilai et al. occurred in the presence of weight loss, a role for leptin-associated reduced energy intake as a cofactor must also be considered. In addition to these central effects, leptin has also been shown to act peripherally, e.g. by activation of AMP kinase (37), up-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (38), and other effects that may contribute to enhanced lipid disposal. Our findings in humans therefore emphasize that further studies are required to determine the exact neuroendocrine and other mechanism(s) by which leptin reduces VAT.

Leptin administration was associated with marked improvements in dyslipidemia in a group of patients who, for the most part, were already treated with lipid-lowering agents. Total, LDL, and non-HDL cholesterol decreased by 15–20%, whereas HDL-C increased by a similar amount. In addition, triglyceride levels, measured under fasting, hyperinsulinemic, and postprandial conditions, decreased by about 30%. Because subjects who were on lipid-lowering therapies were required to have been on stable treatment for at least 3 months before enrolling, it is unlikely that the observed improvements were a result of the hypolipidemic agents, whose effects are generally seen within the first 4 wk of treatment. To our knowledge, no one has shown that weight loss per se can produce reductions in LDL-C of this magnitude. Our results are consistent with the results of studies in patients with non-HIV lipodystrophy, in which striking reductions in triglyceride levels were achieved during leptin treatment (10,12). The magnitude of the changes in lipids observed in the present study is comparable with or greater than that seen in studies of other lipid-lowering agents in HIV-infected populations (39,40,41,42,43) and exceeds that achieved by experimental therapy with GH (25,26,28) or a synthetic GHRH (29). Given the difficulty in treating dyslipidemia in HIV-infected subjects, as manifest by the abnormal values in this cohort of subjects, nearly all of whom were on hypolipidemic therapy, the improvement in lipids profile raises the possibility that leptin therapy could potentially reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Leptin administration was also associated with decreases in fasting insulin levels, as has been observed in other studies (10,11,12). There has been less consistency in results of studies that used dynamic measures of peripheral insulin sensitivity: Petersen et al. (44), using a euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp, reported a marked improvement in whole-body glucose uptake in three subjects with non-HIV lipodystrophy. Using an insulin suppression test, Oral et al. (10) also found a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity in patients with non-HIV lipodystrophy. In contrast Lee et al. (11) reported only a trend to improvement in patients with HIV lipodystrophy. Conceivably, the failure to see a significant increase in whole-body glucose uptake in our study, in contrast to those reported in non-HIV lipodystrophy (10,44), may have reflected the relatively mild degree of peripheral insulin resistance at baseline in some of our subjects. However, whereas we did not observe a consistent increase in peripheral insulin sensitivity, we did demonstrate reductions in fasting insulin and glucose levels and suppression of hepatic glucose production, glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis both during fasting and in response to hyperinsulinemia during the clamp, suggesting that leptin treatment improved hepatic insulin sensitivity. Therefore, our results emphasize the importance of considering site-specific effects in metabolic studies of leptin.

Leptin administration also led to a decrease in the rate of lipolysis and FFA levels during both fasting and hyperinsulinemia, suggesting an improvement in insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue. Overexpression of leptin in a transgenic, lipoatrophic mouse model has been shown to decrease lipolysis (45), and a trend to a decrease in lipolysis was observed in three patients with non-HIV lipodystrophy who were treated with leptin (44). It has been suggested that excess lipolysis is an important metabolic feature of HIV lipodystrophy (46).

The design of the current study does not allow us to determine whether the improvements noted after 6 months of leptin treatment are dose or time dependent. In general, the metabolic results after 3 months of treatment fell between those measured at baseline and 6 months. In contrast, the major reduction in VAT appeared to occur between 3 and 6 months, suggesting that a higher dose may be required to achieve a reduction in VAT. These results also raise the possibility that the metabolic effects of leptin are at least in part directly induced by leptin and not a secondary result of the decrease in VAT. However, we did not measure adiponectin, an adipocytokine that is inversely associated with VAT and positively with insulin sensitivity (47). Adiponectin increased during treatment with rosiglitazone (32) or TH9507 (29) in patients with HIV-associated fat accumulation but did not change during leptin treatment in the study of Lee et al. (11). Although subjects were hypoleptinemic at baseline, the dose of leptin used during months 3–6 produced serum leptin levels that were above the upper limit of the normal range for lean adult men (∼14 ng/ml) and thus might be considered supraphysiological. Although leptin was well tolerated, even at the higher dose, the loss of weight and lean tissue seen during treatment cannot be considered to be positive effects.

Two small studies of the metabolic effects of leptin in HIV-infected patients with lipoatrophy and hypoleptinemia have now been completed, with some similarities and differences. Lee et al. (11) used a dose of 0.02 mg/kg twice daily in a placebo-controlled crossover design. The dose of leptin used in the study of Lee et al. was in between the two doses used in our open-label study, and the treatment duration was shorter (2 months in the study of Lee et al. vs. 6 months in our study). Seven subjects were treated, and five subjects completed both phases of the Lee study, whereas all eight subjects who entered our study completed 6 months of treatment. Based on the use of surrogate measures of insulin sensitivity (fasting insulin, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, insulin suppression test), Lee et al. concluded that leptin improved insulin sensitivity. Although we, too, observed decreases in fasting insulin, our study used the criterion method for measuring whole-body glucose uptake, the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp, along with stable isotope tracer technology, and found that although leptin improved hepatic insulin sensitivity, it had no effect on peripheral insulin sensitivity. Thus, our results provide novel information on the specific sites of leptin’s effects on insulin sensitivity. Subjects in both studies had decreases in weight and trunk fat, increases in HDL-C, and trends to decreases in LBM. However, in contrast to reductions in triglyceride levels and LDL-C in our study, no such changes were seen in the study of Lee et al. (11). The design of the study by Lee et al. required subjects to have triglyceride levels between 300 and 1000 mg/dl in the absence of lipid lowering therapy at baseline, and two subjects were withdrawn during the study when triglycerides exceeded 1000 mg/dl. We cannot speculate on whether the absence of decreases in triglycerides and LDL-C in their study was a result of this or other differences in study design such as the use of a lower dose of leptin or a shorter duration of treatment. Overall, we conclude that the optimal therapeutic dose of leptin and effective treatment period are not yet known.

In conclusion, results from this open-label pilot study demonstrate that treatment with leptin was well tolerated and led to significant improvements in dyslipidemia, lipolysis, and hepatic insulin sensitivity that were accompanied by a marked decrease in VAT. These improvements occurred without any apparent exacerbation of peripheral lipoatrophy. These findings suggest that leptin may have therapeutic potential in HIV-infected patients with metabolic and morphologic alterations in association with lipoatrophy and warrant a larger, placebo-controlled trial in this population.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance of the San Francisco General Hospital-General Clinical Research Center nursing, dietary, and laboratory staff; and Raj Periasamy, Dr. Seungki Kim, Dr. Seongsoo Park, Daniel McCoy, Sara Davis-Eisenman, and Art Moser. Leptin was generously provided by Amgen, Inc. Leptin is now produced by Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK63640, DK54615, DK66999, and RR-00083; University of California Universitywide AIDS Research Program Grant CF02-SF-302; Amgen, Inc.; and Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Disclosure Summary: H.K., J.-M.S., G.K.S., V.W.T., M.J.W., G.A.L., and C.G. have nothing to declare. K.M. and M.S. received consulting fees from Amgen Inc. and Amylin, Inc. M.S. received the drug used in this National Institutes of Health-funded study and a small research grant from Amgen; the latter was transferred to Amylin. A.M.D. was employed at Amgen Inc. at the time of this research.

First Published Online January 27, 2009

For editorial see page 1089

Abbreviations: AUC, Area under the curve; FFA, free fatty acid; GCRC, General Clinical Research Center; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LBM, lean body mass; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; Ra, rate of appearance; SAT, sc abdominal adipose tissue; VAT, visceral abdominal adipose tissue.

References

- Reitman ML, Gavrilova O 2000 A-ZIP/F-1 mice lacking white fat: a model for understanding lipoatrophic diabetes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24(Suppl 4): S11–S14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Ikemoto S, Bashmakov Y, Goldstein JL, Brown MS 1998 Insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in transgenic mice expressing nuclear SREBP-1c in adipose tissue: model for congenital generalized lipodystrophy. Genes Dev 12:3182–3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova O, Marcus-Samuels B, Graham D, Kim JK, Shulman GI, Castle AL, Vinson C, Eckhaus M, Reitman ML 2000 Surgical implantation of adipose tissue reverses diabetes in lipoatrophic mice. J Clin Invest 105:271–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy GS, Tsiodras S, Martin LD, Avihingsanon A, Gavrila A, Hsu WC, Karchmer AW, Mantzoros CS 2003 Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy are associated with serum concentrations of leptin. Clin Infect Dis 36:795–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl D, Scherzer R, Heymsfield S, Simberkoff M, Sidney S, Bacchetti P, Grunfeld C 2008 The associations of regional adipose tissue with lipid and lipoprotein levels in HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 48:44–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitman ML, Arioglu E, Gavrilova O, Taylor SI 2000 Lipoatrophy revisited. Trends Endocrinol Metab 11:410–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque WA, Shimomura I, Matsuzawa Y, Garg 2002 A Serum adiponectin and leptin levels in patients with lipodystrophies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2395–2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Ikemoto S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL 1999 Leptin reverses insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in mice with congenital lipodystrophy. Nature 401:73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asilmaz E, Cohen P, Miyazaki M, Dobrzyn P, Ueki K, Fayzikhodjaeva G, Soukas AA, Kahn CR, Ntambi JM, Socci ND, Friedman JM 2004 Site and mechanism of leptin action in a rodent form of congenital lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest 113:414–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral EA, Simha V, Ruiz E, Andewelt A, Premkumar A, Snell P, Wagner AJ, DePaoli AM, Reitman ML, Taylor SI, Gorden P, Garg A 2002 Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N Engl J Med 346:570–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Chan JL, Sourlas E, Raptopoulos V, Mantzoros CS 2006 Recombinant methionyl human leptin therapy in replacement doses improves insulin resistance and metabolic profile in patients with lipoatrophy and metabolic syndrome induced by the highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:2605–2611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara K, Kusakabe T, Hirata M, Masuzaki H, Miyanaga F, Kobayashi N, Tanaka T, Chusho H, Miyazawa T, Hayashi T, Hosoda K, Ogawa Y, DePaoli AM, Fukushima M, Nakao K 2007 Efficacy and safety of leptin-replacement therapy and possible mechanisms of leptin actions in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:532–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo JC, Mulligan K, Tai VW, Algren H, Schambelan M 1998 “Buffalo hump” in men with HIV-1 infection. Lancet 351:867–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naressi A, Couturier C, Castang I, de Beer R, Graveron-Demilly D 2001 Java-based graphical user interface for MRUI, a software package for quantitation of in vivo/medical magnetic resonance spectroscopy signals. Comput Biol Med 31:269–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniak LS, Babcock EE, Schick F, Dobbins RL, Garg A, Burns DK, McGarry JD, Stein DT 1999 Measurement of intracellular triglyceride stores by H spectroscopy: validation in vivo. Am J Physiol 276:E977–E989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R 1979 Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol 237:E214–E223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA 1997 In vivo measurement of insulin sensitivity in humans. In: Drasnin B, Rizza R, eds. Clinical research in diabetes and obesity. Vol 1. Methods, assessment, and metabolic regulation. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc.; 23–65 [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe RR 1992 Radioactive and stable isotope tracers in biomedicine: principles and practice of kinetic analysis. New York: Wiley-Liss [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstein MK, Neese RA 1992 Mass isotopomer distribution analysis: a technique for measuring biosynthesis and turnover of polymers. Am J Physiol 263:E988–E1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese RA, Schwarz JM, Faix D, Turner S, Letscher A, Vu D, Hellerstein MK 1995 Gluconeogenesis and intrahepatic triose phosphate flux in response to fasting or substrate loads. J Biol Chem 270:14452–14463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrannini E 1988 The theoretical bases of indirect calorimetry: a review. Metabolism 3:287–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzer R, Shen W, Bacchetti P, Kotler D, Lewis CE, Shlipak MG, Punyanitya M, Heymsfield SB, Grunfeld C 2008 Comparison of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and magnetic resonance imaging-measured adipose tissue depots in HIV-infected and control subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 88:1088–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, Buse J, DeFronzo R, Kahn R, Kitzmiller J, Knowler WC, Lebovitz H, Lernmark A, Nathan D, Palmer J, Rizza R, Saudek C, Shaw J, Steffes M, Stern M, Tuomilehto J, Zimmet P 2003 Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 26:3160–3167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymsfield SB, Greenberg AS, Fujioka K, Dixon RM, Kushner R, Hunt T, Lubina JA, Patane J, Self B, Hunt P, McCamish M 1999 Recombinant leptin for weight loss in obese and lean adults: a randomized, controlled, dose-escalation trial. JAMA 282:1568–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler DP, Muurahainen N, Grunfeld C, Wanke C, Thompson M, Saag M, Bock D, Simons G, Gertner JM 2004 Effects of growth hormone on abnormal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and dyslipidemia in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 35:239–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld C, Thompson M, Brown SJ, Richmond G, Lee D, Muurahainen N, Kotler DP 2007 Recombinant human growth hormone to treat HIV-associated adipose redistribution syndrome: 12 week induction and 24-week maintenance therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 45:286–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo JC, Mulligan K, Noor M, Schwarz J-M, Halvorsen RA, Grunfeld C, Schambelan M 2001 The effects of recombinant human growth hormone on body composition and glucose metabolism in HIV-infected patients with fat accumulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3480–3487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Mulligan K, Lee J, Lo JC, Wen M, Noor MA, Grunfeld C, Schambelan M 2002 Effects of recombinant human growth hormone on hepatic lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in HIV-infected patients with fat accumulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:942–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falutz J, Allas S, Blot K, Potvin D, Kotler D, Somero M, Berger D, Brown S, Richmond G, Fessel J, Turner R, Grinspoon S 2007 Metabolic effects of a growth hormone-releasing factor in patients with HIV. N Engl J Med 357:2359–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadigan C, Yawetz S, Thomas A, Havers F, Sax PE, Grinspoon S 2004 Metabolic effects of rosiglitazone in HIV lipodystrophy: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 140:786–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk JP, de Koning EJ, Cabezas MC, op’t Roodt J, Joven J, Rabelink TJ, Hoepelman AI 2005 Comparison of rosiglitazone and metformin for treating HIV lipodystrophy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 143:337–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan K, Yang Y, Wininger DA, Koletar SL, Parker RA, Alston-Smith BL, Schouten JT, Fielding RA, Basar MT, Grinspoon S 2007 Effects of metformin and rosiglitazone in HIV-infected patients with hyperinsulinemia and elevated waist/hip ratio. AIDS 21:47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadigan C, Corcoran C, Basgoz N, Davis B, Sax P, Grinspoon S 2000 Metformin in the treatment of HIV lipodystrophy syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 284:472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli R, Shevitz A, Gorbach S, Wanke C 2007 A randomized placebo-controlled trial of metformin for the treatment of HIV lipodystrophy. HIV Med 8:420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Zachwieja JJ 1999 Visceral adipose tissue: a critical review of intervention strategies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 23:329–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N, Wang J, Massilon D, Vuguin P, Hawkins M, Rossetti L 1997 Leptin selectively decreases visceral adiposity and enhances insulin action. J Clin Invest 100:3105–3110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Peroni OD, Fryer LG, Muller C, Carling D, Kahn BB 2002 Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature 415:339–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Yu X, Gonzales F, Mangelsdorf DJ, Wang MY, Richardson C, Witters LA, Unger RH 2002 PPARα is necessary for the lipopenic action of hyperleptinemia on white adipose and liver tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:11848–11853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberg JA, Zackin RA, Brobst SW, Evans SR, Alston BL, Henry WK, Glesby MJ, Torriani FJ, Yang Y, Owens SI, Fichtenbaum CJ 2005 A randomized trial of the efficacy and safety of fenofibrate versus pravastatin in HIV-infected subjects with lipid abnormalities: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 5087. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 21:757–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallon PW, Miller J, Kovacic JC, Kent-Hughes J, Norris R, Samaras K, Feneley MP, Cooper DA, Carr A 2006 Effect of pravastatin on body composition and markers of cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected men-a randomized, placebo-controlled study. AIDS 20:1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calza L, Colangeli V, Manfredi R, Legnani G, Tampellini L, Pocaterra D, Chiodo F 2005 Rosuvastatin for the treatment of hyperlipidaemia in HIV-infected patients receiving protease inhibitors: a pilot study. AIDS 19:1103–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube MP, Wu JW, Aberg JA, Deeg MA, Alston-Smith BL, McGovern ME, Lee D, Shriver SL, Martinez AI, Greenwald M, Stein JH 2006 Safety and efficacy of extended-release niacin for the treatment of dyslipidaemia in patients with HIV infection: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5148. Antivir Ther 11:1081–1089 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber JG, Kitch DW, Fichtenbaum CJ, Zackin RA, Charles S, Hogg E, Acosta EP, Connick E, Wohl D, Kojic EM, Benson CA, Aberg JA 2008 Fish oil and fenofibrate for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia in HIV-infected subjects on antiretroviral therapy: results of ACTG A5186. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 47:459–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KF, Oral EA, Dufour S, Befroy D, Ariyan C, Yu C, Cline GW, DePaoli AM, Taylor SI, Gorden P, Shulman GI 2002 Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest 109:1345–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Y, Qiu J, Ogus S, Shen WJ, Kraemer FB, Chehab FF 2003 Overexpression of leptin in transgenic mice leads to decreased basal lipolysis, PKA activity, and perilipin levels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 312:1165–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar RV, Jahoor F, White AC, Pownall HJ, Visnegarwala F, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Sharma M, Reeds PJ, Balasubramanyam A 2002 Metabolic basis of HIV-lipodystrophy syndrome. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283:E332–E337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnop M, Havel PJ, Utzschneider KM, Carr DB, Sinha MK, Boyko EJ, Retzlaff BM, Knopp RH, Brunzell JD, Kahn SE 2003 Relationship of adiponectin to body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity and plasma lipoproteins: evidence for independent roles of age and sex. Diabetologia 46:459–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]