Abstract

Motivation: Modern anatomical and developmental studies often require high-resolution imaging of large specimens in three dimensions (3D). Confocal microscopy produces high-resolution 3D images, but is limited by a relatively small field of view compared with the size of large biological specimens. Therefore, motorized stages that move the sample are used to create a tiled scan of the whole specimen. The physical coordinates provided by the microscope stage are not precise enough to allow direct reconstruction (Stitching) of the whole image from individual image stacks.

Results: To optimally stitch a large collection of 3D confocal images, we developed a method that, based on the Fourier Shift Theorem, computes all possible translations between pairs of 3D images, yielding the best overlap in terms of the cross-correlation measure and subsequently finds the globally optimal configuration of the whole group of 3D images. This method avoids the propagation of errors by consecutive registration steps. Additionally, to compensate the brightness differences between tiles, we apply a smooth, non-linear intensity transition between the overlapping images. Our stitching approach is fast, works on 2D and 3D images, and for small image sets does not require prior knowledge about the tile configuration.

Availability: The implementation of this method is available as an ImageJ plugin distributed as a part of the Fiji project (Fiji is just ImageJ: http://pacific.mpi-cbg.de/).

Contact: tomancak@mpi-cbg.de

1 INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing demand to image complete biological specimens with high resolution in two and three dimensions. Biologists use Confocal, Bright field or Electron microscopes equipped with motorized stages to stepwise image large areas using high magnifications. The acquired image tiles have to be combined into one final output image by a process usually referred to as Stitching. Motorized stages used for such acquisitions operate with high precision, however, in most cases the physical coordinates from the stage are not precise enough to provide a proper reconstruction of the whole acquisition on the pixel level. Moreover, in some cases the approximate configuration of the tiles may be unknown.

To overcome these problems, we present a method capable of stitching sets of 2D and 3D images. The method uses phase correlation (Kuglin and Hines, 1975) to find the translation between all image pairs and registers multi-tile acquisitions globally minimizing all pairwise registration errors. The global approach allows stitching even without prior knowledge of tile configuration. Additionally, we implemented non-linear blending to compensate brightness differences between the image tiles to create artifact-free, stitched output images.

2 METHODS

The acquisition results in a set of n image tiles where a subset overlaps such that all images form a connected graph. The method has to determine the correct overlap for all tiles and create a properly registered output image containing all image tiles that are connected to the graph.

We assume all transformations between overlapping tiles to be translation only which is reasonable for most commonly used microscopy techniques where the static, fixed sample rests on a level microscope slide moved by a motorized stage.

2.1 Phase correlation and fast Fourier transform

We use the Fourier transform (ℱ)-based phase correlation method (PCM) (Kuglin and Hines, 1975) to compute translational offsets between images. If two images A and B are related by translation, the shift (x, y, z)⊤ can be computed from inverse Fourier transform (ℱ−1) of the phase correlation matrix 𝒬 (ℱ(A), ℱ(B)). It is theoretically represented by a single peak (δ-function) whose location defines the correct translation vector between the images.

In real images, however, ℱ−1(𝒬) contains several peaks marking different translations with high correlation. Moreover, each peak describes eight different possible translations (in 3D) due to the periodicity of the Fourier space. To determine the correct shift, we select the n highest local maxima (3 × 3 × 3 neighborhood) from ℱ−1(𝒬) and evaluate their eight possible translations by means of cross-correlation on the overlapping area of the images A, B. The peak with the highest correlation is selected as translation between the two images. If none of the peaks is above a certain limit the tiles are assumed to be non-overlapping.

The Fourier transform ℱ is computed using the multi-threaded Prime Factor Fast Fourier Transform (PFFFT) (Good, 1958). Prior to performing the PFFFT the input images have to be extended to a size supported by that algorithm. To overcome sharp edges resulting from zero padding, we extend the images by the mirrored image content faded from its real intensity to black using an exponential windowing function. In this way, the periodicity is not broken and real image information is preserved as only the mirrored parts are faded out. The resulting images are zero-padded to dimensions supported by the PFFFT algorithm.

2.2 Globally optimized registration

The PCM results in a set of translations  with V being the set of all tiles, and each

with V being the set of all tiles, and each  mapping tile A to an overlapping tile B maximizing the pairwise alignment quality. Consecutive placement of tiles into the output image would lead to the propagation of alignment errors as the independent pairwise transforms may conflict when the position of a tile is defined by more than one neighbor. We avoid error propagation by minimizing the sum of all pairwise transfer errors by means of least squares. Given that F ∈ V is a fixed tile that defines the common reference frame, the optimal configuration

mapping tile A to an overlapping tile B maximizing the pairwise alignment quality. Consecutive placement of tiles into the output image would lead to the propagation of alignment errors as the independent pairwise transforms may conflict when the position of a tile is defined by more than one neighbor. We avoid error propagation by minimizing the sum of all pairwise transfer errors by means of least squares. Given that F ∈ V is a fixed tile that defines the common reference frame, the optimal configuration  is defined as

is defined as

The solution of this term gives the set of all translational parameters and the displacement relative to the initially estimated pairwise translation (Table 1). Overlapping tiles for which no initial translation was found may still be connected through other images. Additionally, by checking the ratio between maximal and average displacement, we are able to detect misaligned tiles, where pairwise PCM failed to identify correct translation. If the maximal displacement is significantly larger than the average displacement then the alignment of the image pair with the highest displacement is removed and TVF is recalculated. If tiles become disconnected from all their neighbors they will not contribute to the output image. These are usually tiles without content.

Table 1.

Examples of stitching performance on tiled microscopy data computed on an Intel® Quad-Core CPU machine with 2.67 GHz and 24 GB of RAM

| Tiles | Single-tile | Output image | Comp. time | Min/avg/max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dimension | size | (min:sec) | displacement (pixel) | |

| 3 | 10242 × 42 | 108 MB | 0:42 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 |

| 6 | 5122 × 86 | 350 MB | 1:20 | 0.60/0.77/1.05 |

| 24 | 10242 × 68 | 1.2 GB | 22:43 | 0.49/0.76/0.99 |

| 72 | 5122 × 122 | 1.9 GB | 43:10 | 0.00/0.39/0.64 |

| 63 | 10242 × 92 | 5.4 GB | 178:57 | 0.00/0.66/1.18 |

The global alignment adjusts the position of individual tiles up to about 1 pixel.The six tile dataset in row 2 is RGB all other are gray-scale.

2.3 Non-linear blending

Microscopic acquisitions suffer from shading, a position-dependent additive term to the pixel intensity resulting in clearly visible brightness differences in the overlapping areas of adjacent tiles. Background subtraction prior to stitching is problematic for confocal microscopy images that lack background intensities in the absence of a specimen.

To compensate for shading differences between tiles, we apply a weighting factor to each pixel in each contributing tile. The applied factor is based on the exponentially weighted distance of the current pixel coordinate from its own tile boundary. Thus, the non-linear blending creates a weighting map for each tile that has high influence on the central pixels and zero influence on pixels at the edge of the image. The non-linearity of the 3D weight function is determined by the tunable parameter α [α=0 blending by averaging, α=1 linear blending (Brown and Lowe, 2007), α > 1 non-linear blending).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We used the presented method to reconstruct several types of tiled microscopy acquisitions (Table 1, Fig. 1) ranging from mosaics of histological 2D images to sets of gray-scale and RGB 3D confocal stacks. The reconstructed images show no stitching artifacts, either from misalignments or from intensity leaps in the overlapping areas (http://fly.mpi-cbg.de/preibisch/stitching.html).

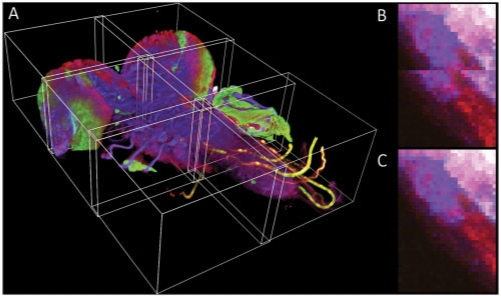

Fig. 1.

Stitching results. (A) The 3D visualization of stitched 2 × 3 mosaic of the central nervous system of a Drosophila larva (Table 1, row 2). The displacements of individual 3D stacks are artificially exaggerated. (B,C) A close up of the border between adjacent tiles as recorded by the microscope stage (B) and after the application of the stitching method (C).

The globally optimized registration finishes with low average and maximal displacement and does not discard any non-uniform image tiles (Table 1). Moreover, the method is capable of reconstructing even mosaics with an unknown configuration of the tiles. In this case, the PCM is computed for all tile pairs (i.e. all tiles are assumed to overlap), connections that result in inconsistent or low-quality alignments are sequentially dropped from the connection graph until only the truly overlapping tiles remain in the graph.

The program is fully multi-threaded taking advantage of multi-core CPUs. Typically, registration consumes significantly less time than image acquisition. The method is applicable to virtually any type of microscopy image data as it uses LOCI bioformat standard for import. The method is implemented as a plugin for the fully open source ImageJ ((Rasband, 2008)) distribution called Fiji that is actively maintained and expanded by an international community of developers ensuring long-term availability and future improvements of the stitching method. All operations of the plugin and the required parameters are extensively documented (http://fly.mpi-cbg.de/preibisch/manual).

The described stitching algorithm represents an open source solution for efficient reconstruction of large 2D and 3D image mosaics, which will become increasingly important for analysis of large biological specimens with the high resolution offered by modern microscopy techniques.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank James W. Truman, Nicolas Gompel and Simone Fietz for providing unpublished images. We also thank Benjamin Schmidt and the Fiji team for providing programming libraries.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Brown M, Lowe DG. Automatic panoramic image stitching using invariant features. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2007;74:59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Good IJ. The interaction algorithm and practical Fourier analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1958;20:361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Kuglin CD, Hines DC. The phase correlation image alignment method. Proceedings of the IEEE, International Conference on Cybernetics and Society. 1975:163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rasband W. ImageJ: image processing and analysis in Java [version 1.40g] [Google Scholar]