Abstract

Precise arrangement of nanoscale elements within larger systems, is essential to controlling higher order functionality and tailoring nanophase material properties. Here, we present findings on growth conditions for vertically aligned carbon nanofibers that enable synthesis of high density arrays and individual rows of nanofibers, which could be used to form barriers for restricting molecular transport, that have regular spacings and few defects. Growth through plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition was initiated from precisely formed nickel catalyst dots of varying diameter and spacing that were patterned through electron beam lithography. Nanofiber growth conditions, including power, precursor gas ratio, growth temperature and pressure were varied to optimize fiber uniformity and minimize defects that result from formation and migration of catalyst particles prior to growth. It was determined that both catalyst dot diameter and initial plasma power have a considerable influence on the number and severity of defects, while growth temperature, gas ratio (C2H2:NH3) and pressure can be varied within a considerable range to fine-tune nanofiber morphology.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of nanostructure synthesis techniques has changed the way that researchers approach materials science and the construction of micro-scale systems. The ability to probe and manipulate materials at the nanoscale has made it possible to explore the influence of nanoscale organization and individual nanoscale element properties on bulk material performance [1–6]. Top-down microfabrication techniques, aimed at patterning progressively smaller features, and bottom-up techniques, aimed at the assembly of molecular elements into nanostructures, are converging. Still, a significant challenge exists in integrating conventional microfabricated devices and nanoscale elements into systems that are functional across all of the relevant length scales.

A significant body of work exists that describes the synthesis and material properties of vertically aligned carbon nanofibers (VACNFs). The impact of pressure, temperature, gas ratio, choice of catalyst material, and even catalyst geometry on fiber morphology and growth rate have been explored [7–16]. Furthermore, the integration of ensembles of individual fibers and stochastic nanofiber forests into functional devices for electrochemical and biochemical sensing [17–26], gated-cathode field emitters [27–29], barriers to material transport [30–32] and templates for the synthesis of nanofluidic nozzles, or nanopipes [33,34], has also been described. These ensembles have benefited from fiber redundancy and as such are not impacted significantly by isolated defects in the form of missing or migrated fibers. Here, we focused on the patterning and synthesis of VACNFs for the creation of narrow nanofiber barriers of defined structure from high density ordered arrays and single rows of nanofibers. Particular emphasis was placed on elucidating the factors that contribute most significantly to the presence of defects that impact device yield. Such defects are largely attributable to fiber migration from the intended location.

The yield of micro-scale devices whose function is dependent upon the coordinated function of large numbers of individual nanoscale elements is severely impacted by losses of individual nanoscale elements. For example, with an element yield of 99.5%, a device requiring the coordinated function of one hundred fibers each, would, on average, be produced successfully in only 60% of attempts, based on the percent probability (P) of 100 events that occur 99.5% of the time occurring simultaneously (P = 100 * 0.995100). In cases such as this where a single defect is fatal, even small increases in element yield produce large increases in device yield. In the example described, an increase of 0.1% in element yield (to 99.6%) would lead to a 10% increase in device yield (to 67%).

The synthesis of the arrays of VACNFs consists of several stages, each of which is potentially a point of control and a source of defects. The first stage is preparation of thin film islands of catalyst material by means of physical vapor deposition through lithographically patterned resist masks. The second stage is pretreatment of the catalyst films that leads to their conversion to catalyst nanoparticles. This process is initiated by dewetting of the film by raising the temperature of the film via conduction through the substrate, laser irradiation, or ion irradiation. It is believed that dewetting is facilitated by exposure to a reducing atmosphere of hydrogen (gas or plasma), which presumably removes the thin oxide film from the catalyst metal. When the film is dewetted, metal droplets are mobile and can migrate from the intended position. The last stage of the process is nanofiber growth, initiated by of the introduction of a carbonaceous gas. As soon as the first carbon layers are formed under the particle, its location, and the location fiber which forms underneath, become fixed. At this stage the catalyst nanoparticle is located at the tip of the growing nanofiber, and processes at its surface determine the direction of nanofiber growth. In this work, aspects of all three stages that are necessary to make a high density regular array of carbon nanofibers were investigated.

2. Experimental

2.1. Catalyst definition

Nickel catalyst patterns were defined using electron beam lithography and conventional metal lift-off techniques. Silicon <100> wafers were spin coated with 495 PMMA A4 resist (Microchem Corp., Newton, MA) having a nominal thickness of 200 nm (spun at 2500 RPM for 1 min). Samples were then soft-baked at 170 °C for 10 min. Resist was exposed using a Jeol-6300FS/E electron beam lithography system operating at a current of 1 nA and an accelerating potential of 50 kV at doses ranging from 380 mC/cm2 to 440 mC/cm2. Patterns were developed in 1:3 MIBK:IPA NANO™PMMA and Copolymer Developer (Microchem Corp., Newton, MA) for 1 min. A descum was performed by reactive ion etching samples in an oxygen plasma for 10 s. Deposition of 10 nm of titanium and 30 nm of nickel was performed via electron beam evaporation at 2 × 10−6 torr. Lift-off was performed overnight in Microposit® Remover 1165. Ultrasonification in the remover for 30 s was used to assist lift-off. Samples were sequentially rinsed with IPA and water, then blown dry with nitrogen.

2.2. Carbon nanofiber growth

Nanofiber growth was performed in a glow-discharge DC plasma consisting of an acetylene: ammonia gas mixture at 500 °C or 550 °C. Plasma pressure was 10 or 6 torr, and the gas ratio of C2H2:NH3 were varied between 0.40 and 0.75. Plasma power was adjusted by controlling current from 1 to 2.5 A during growth. The actual temperature of the substrate with plasma on was higher than the temperature of the substrate heater. The difference was estimated with infrared pirometer to be as high as 100 °C at 2 A. Growth parameters were adjusted to produce well-aligned, high-aspect ratio fibers with a height of 10 μm.

3. Results and discussion

Patterns consisted of 10-, 25- and 100 μm square cells bounded by single or staggered rows of catalyst dots with diameters of 250 or 350 nm at pitches of 0.8, 1, 1.2 and 1.4 μm. High density ordered arrays of 250 nm dots at a radial pitch of 0.7 and 1 μm were also created. Preliminary experiments using patterned dots ranging in diameter from 100 to 400 nm indicated that smaller dots (50–100 nm in diameter) did not provide sufficient catalyst to grow fibers of the desired height (5–10 μm), while dots with diameters larger than 350 nm were susceptible to break-up and formation of fibers with multiple tips.

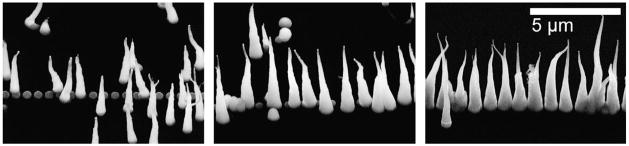

Fiber morphology and growth rate are known to vary as a function of gas ratio [9]. Here, we examined the influence of plasma power on fiber placement and growth. Initial experiments (Fig. 1) revealed a dramatic increase in the fidelity of fiber placement as the plasma current was increased from 1 to 2 A (Fig. 1). Based on the observation of the patterned titanium adhesion layer where catalyst had been deposited but fibers were absent, and the relative lack of partially grown fibers, it was hypothesized that placement inaccuracy was the result of nickel particle migration prior to the initiation of nanofiber growth. We reasoned that more accurate placement could therefore be achieved by increasing current, and hence deposition rate, during the first few minutes of fiber growth in order to shorten the time between particle dewetting and initiation of fiber growth.

Fig. 1.

Effect of plasma current on nanofiber migration during growth. SEM images of fibers grown with plasma currents of 1.0 A (left), 1.5 A (center) and 2.0 A (right) are shown (tilt = 30°.). Other growth parameters were held constant (C2H2:NH3 = 0.75, 500 °C, 10 torr). Portions of the titanium adhesion layer, exposed upon catalyst migration, are visible in the left and center as light, round spots. Accurate placement of CNFs is dependent upon the current used to control plasma power during growth.

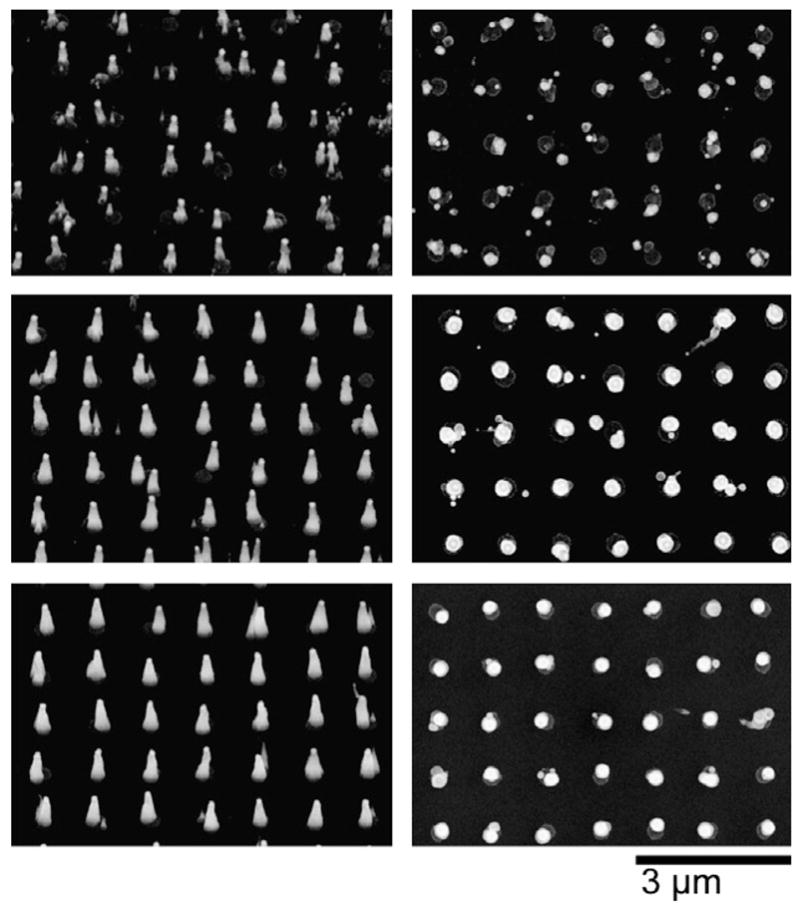

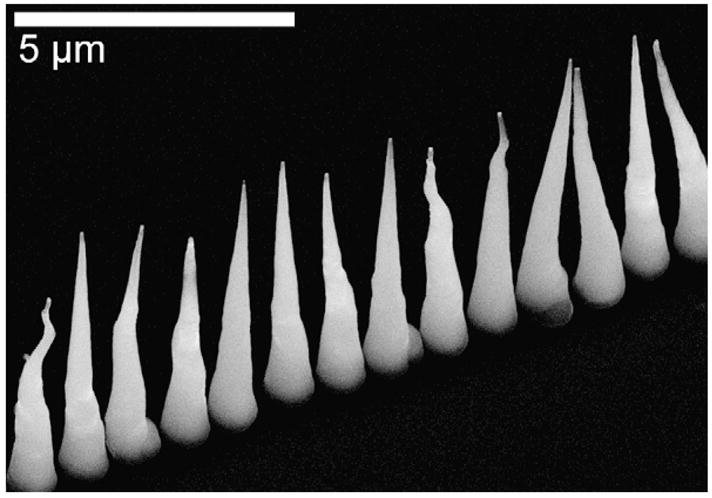

To verify our assumption that migration occurs during the early stages of fiber growth, short duration growths of nanofiber arrays were conducted. We had observed that growths at 6 torr and 550 °C led to better vertical alignment than more rapid growths conducted at 10 torr and 500 °C; as such the short duration growths and the remainder of experiments described were conducted at 6 torr and 550 °C. SEM analysis was conducted on high density arrays grown at plasma currents of 1.5 A for 2 min, 2 A for 2 min, and 2.5 A for 1 min followed by 2.25 A for 1 min (Fig. 2). These experiments confirmed the dependence of fiber placement on plasma power and indicated that fiber migration occurs early in the growth process. The rapid-start approach, in which current was decreased progressively from an initial high of 2.5 A, provided the best result. By using both the rapid-start process to lock down the fibers and the improved pressure/temperature combination, we were able to realize great improvement in fiber-positioning fidelity and more consistent morphology. Fig. 3 shows a single row of deterministically grown fibers made using the improved protocol, with Fig. 1 providing the point of comparison.

Fig. 2.

Short-duration nanofiber growths at varying plasma power. SEM images of short duration (2 min) growths demonstrate the strong dependence of fiber placement on initial current. Sample tilt was 30° (left) and 0° (right). Growths were performed at a controlled current of 1.5A (top), 2 A (middle) and 2.5 (1 min) +2.25 A (1 min) (bottom). Other growth parameters were held constant. (90:160 C2H2:NH3, 550 °C, 6T).

Fig. 3.

Single row of nanofibers grown using a fast-start growth process. Accurate placement and good vertical alignment of CNFs was achieved through growth at 6 torr and 550 °C (C2H2:NH3 = 0.6) with a progressive decrease in plasma power: 2.5 A (1 min), 2.25 A (1 min), and 2 A (10 min).

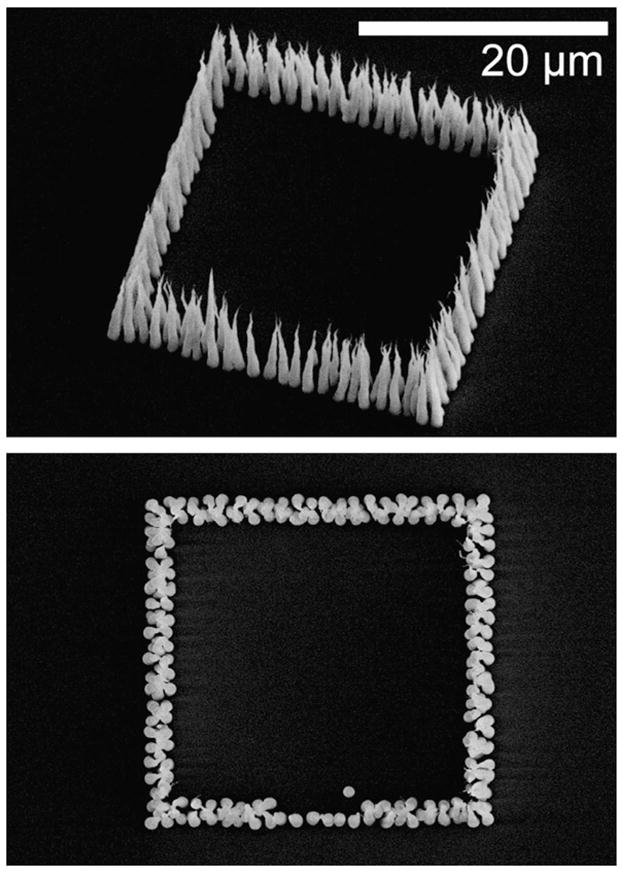

Improved procedures for accurate placement of nanofibers promise to expand the scope of useful structures and devices that can be contemplated. The accuracy achieved with the protocol described is such that we have been able to construct nanofiber chambers on the scale of a mammalian cell (25 μm) consisting of 250–300 fibers, as shown in Fig. 4. In these chambers, staggered arrays of nanofibers create well-defined permeability barriers. For narrow barriers (consisting of just a few rows) to be effective, they must be highly regular and have few defects. Image analysis of four cell structures composed of a total of 2100 fibers for each set of growth conditions and catalyst particle sizes demonstrated fiber placement accuracies of 99.86% and 100% for 250 nm and 350 nm diameter catalyst particles, respectively grown at gas ratios of 100:160 (sccm acetylene:sccm ammonia). With a gas ratio of 85:160, placement accuracies were slightly lower, at 98.14% and 99.95%. While further work is necessary to investigate the effects of other growth parameters, it is clear that growths conducted at higher initial currents can be used to synthesize essentially defect-free single row barriers and ordered nanofiber arrays with reasonable yields. The taper, or conical nature of the fibers, results from sidewall deposition of silicon nitride during the deposition process as discussed by Melechko et al. [7] In Fig. 5, an ordered fiber array is shown next to a random nanofiber forest, contrasting the difference in density and consistency of morphology of fibers grown from catalyst particles resulting from discrete patterning (ordered array) and the break-up of a catalyst thin film (random forest).

Fig. 4.

A semi-permeable, 25 μm square cell defined by deterministically grown fibers. The walls of the cell consist of staggered rows of nanofibers that produce a size-restrictive barrier. A mouth at the bottom of the cell is defined by a single row of fibers for increased permeability.

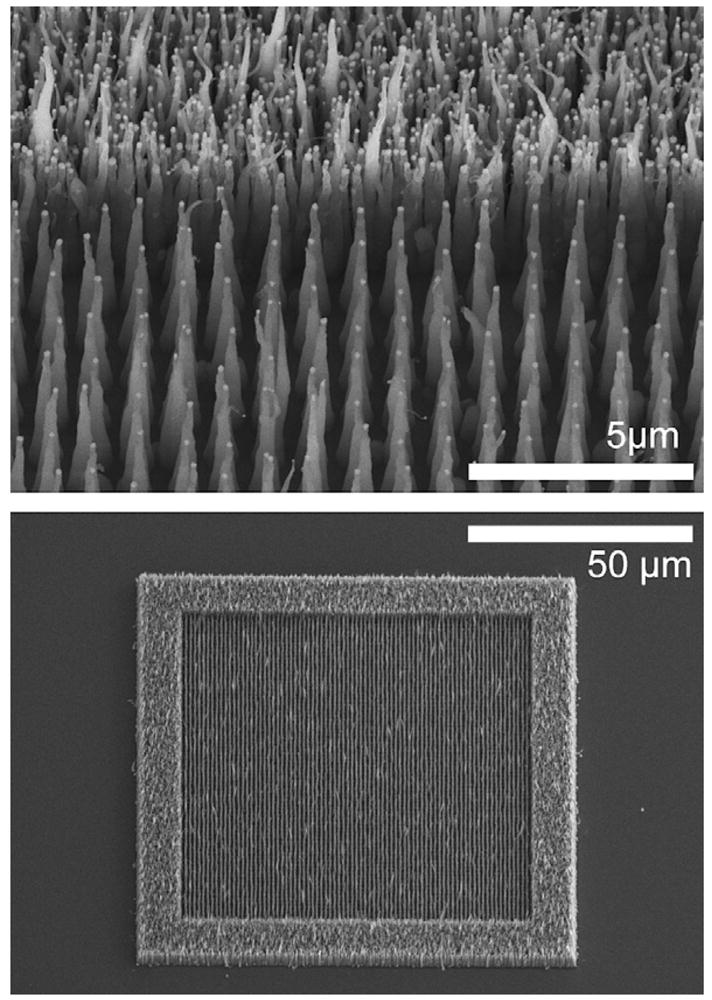

Fig. 5.

An ordered array of deterministically grown nanofibers shown against the backdrop of a randomly grown nanofiber forest shown at high (upper) and low (lower) magnification. Hybrid nanofiber cells having a densely packed outer barrier and crowded interior can be created by combining lithographically defined catalyst stripes that break-up into smaller particles (outer region) with lithographically defined catalyst discs that form into ensembles of single particles having a deterministically controlled size and spacing (inner region).

These nanofiber containers are currently being utilized as cell mimics in studies of molecular transport, and can be used for both the containment of large molecules and to study the diffusion of small molecules in molecularly crowded environments.

4. Conclusions

Controllable integration of nanoscale components into larger multiscale systems is essential for taking advantage of the unique functional properties of such components and for tailoring the properties of a derived system of components. In this work, the positional control of catalyst particles used in nanofiber growth was accomplished by first using established lithographic methods to place catalyst particles and subsequently locking catalyst particles in place by using higher plasma power at the outset of nanofiber growth.

The improvement of catalyst positional control seen at high plasma current suggests that there is a change in the dynamics of the processes involved in particle formation from a thin film catalyst disc. Specifically, the reduction in dwell time (the time between dewetting of the nanoparticle and its immobilization via formation of the first carbon layers) reduce the probability of its movement from the initial location. This work represents the first step in developing a more complete understanding of the full host of mechanisms that impact fiber placement, growth and migration. Ultimately a deeper understanding of these processes will be essential to the large scale integration of carbon nanofibers into functional laboratory and commercial devices.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering grant R01 EB000657. A.V.M. and M.L.S. acknowledge support from the Material Sciences and Engineering Division Program of the Department of Energy Office of Science. A portion of this research was conducted at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is sponsored at Oak Ridge National Laboratory by the Division of Scientific User Facilities (DOE). The authors would also like to thank David Joy, Sachin Dao, and Jihoon Kim for access to the JEOL 6300 FS/E located at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

References

- 1.De Stefano L, Rendina I, De Stefano M, Bismuto A, Maddalena P. Marine diatoms as optical chemical sensors. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;87(23) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fratzl P, Gupta HS, Paschalis EP, Roschger P. Structure and mechanical quality of the collagen-mineral nano-composite in bone. J Mater Chem. 2004;14(14):2115–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fratzl P, Misof K, Zizak I, Rapp G, Amenitsch H, Bernstorff S. Fibrillar structure and mechanical properties of collagen. J Struct Biol. 1998;122(1–2):119–22. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaddis CS, Sandhage KH. Freestanding microscale 3D polymeric structures with biologically-derived shapes and nanoscale features. J Mater Res. 2004;19(9):2541–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakes R. Materials with structural hierarchy. Nature. 1993;361(6412):511–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schadler LS, Giannaris SC, Ajayan PM. Load transfer in carbon nanotube epoxy composites. Appl Phys Lett. 1998;73(26):3842–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melechko AV, McKnight TE, Hensley DK, Guillorn MA, Borisevich AY, Merkulov VI, et al. Large-scale synthesis of arrays of high-aspect-ratio rigid vertically aligned carbon nanofibres. Nanotechnology. 2003;14(9):1029–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melechko AV, Merkulov VI, Lowndes DH, Guillorn MA, Simpson ML. Transition between ‘base’ and ‘tip’ carbon nanofiber growth modes. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;356(5–6):527–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melechko AV, Merkulov VI, McKnight TE, Guillorn MA, Klein KL, Lowndes DH, et al. Vertically aligned carbon nanofibers and related structures: controlled synthesis and directed assembly. J Appl Phys. 2005;97(4) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkulov V, Melechko AV, Guillorn MA, Lowndes DH, Simpson ML. Growth rate of plasma-synthesized vertically aligned carbon nanofibers. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;361(5–6):492–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merkulov VI, Hensley DK, Melechko AV, Guillorn MA, Lowndes DH, Simpson ML. Control mechanisms for the growth of isolated vertically aligned carbon nanofibers. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106(41):10570–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merkulov VI, Melechko AV, Guillorn MA, Lowndes DH, Simpson ML. Alignment mechanism of carbon nanofibers produced by plasma-enhanced chemical-vapor deposition. Appl Phys Lett. 2001;79(18):2970–2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merkulov VI, Melechko AV, Guillorn MA, Lowndes DH, Simpson ML. Effects of spatial separation on the growth of vertically aligned carbon nanofibers produced by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;80(3):476–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merkulov VI, Melechko AV, Guillorn MA, Simpson ML, Lowndes DH, Whealton JH, et al. Controlled alignment of carbon nanofibers in a large-scale synthesis process. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;80(25):4816–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park KH, Lee S, Koh KH, Lacerda R, Teo KBK, Milne WI. Advanced nanosphere lithography for the areal-density variation of periodic arrays of vertically aligned carbon nanofibers. J Appl Phys. 2005;97(2) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teo KBK, Lee SB, Chhowalla M, Semet V, Binh VT, Groening O, et al. Plasma enhanced chemical vapour deposition carbon nanotubes/nanofibres – how uniform do they grow? Nanotechnology. 2003;14(2):204–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker S, Lee CS, Marcus MS, Yang WS, Eriksson M, Hamers RJ. Vertically-aligned carbon nanofibers as electrode materials for biosensing arrays. Abstr Papers Am Chem Soc. 2005;229:U93–3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker SE, Colavita PE, Tse KY, Hamers RJ. Functionalized vertically aligned carbon nanofibers as scaffolds for immobilization and electrochemical detection of redox-active proteins. Chem Mater. 2006;18(18):4415–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamers RJ, Baker S, Lasseter T. Biologically-modified carbon nanotubes: synthesis, biochemical binding, and nanoscale assembly. Abstr Papers Am Chem Soc. 2003;225:U618–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKnight TE, Melechko AV, Austin DW, Sims T, Guillorn MA, Simpson ML. Microarrays of vertically-aligned carbon nanofiber electrodes in an open fluidic channel. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108(22):7115–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKnight TE, Melechko AV, Fletcher BL, Jones SW, Hensley DK, Peckys DB, et al. Resident neuroelectrochemical interfacing using carbon nanofiber arrays. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110(31):15317–27. doi: 10.1021/jp056467j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKnight TE, Melechko AV, Griffin GD, Guillorn MA, Merkulov VI, Serna F, et al. Intracellular integration of synthetic nanostructures with viable cells for controlled biochemical manipulation. Nanotechnology. 2003;14(5):551–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKnight TE, Melechko AV, Griffin GD, Simpson ML. Plant tissue transformation using periodic arrays of vertically aligned carbon nanofibers. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Animal. 2006;42:17A–A. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKnight TE, Melechko AV, Guillorn MA, Merkulov VI, Doktycz MJ, Culbertson CT, et al. Effects of microfabrication processing on the electrochemistry of carbon nanofiber electrodes. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107(39):10722–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKnight TE, Melechko AV, Hensley DK, Mann DGJ, Griffin GD, Simpson ML. Tracking gene expression after DNA delivery using spatially indexed nanofiber Arrays. Nano Lett. 2004;4(7):1213–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKnight TE, Peeraphatdit C, Jones SW, Fowlkes JD, Fletcher BL, Klein KL, et al. Site-specific biochemical functionalization along the height of vertically aligned carbon nanofiber arrays. Chem Mater. 2006;18(14):3203–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guillorn MA, Melechko AV, Merkulov VI, Ellis ED, Britton CL, Simpson ML, et al. Operation of a gated field emitter using an individual carbon nanofiber cathode. Appl Phys Lett. 2001;79(21):3506–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guillorn MA, Melechko AV, Merkulov VI, Hensley DK, Simpson ML, Lowndes DH. Self-aligned gated field emission devices using single carbon nanofiber cathodes. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;81(19):3660–2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guillorn MA, Yang X, Melechko AV, Hensley DK, Hale MD, Merkulov VI, et al. Vertically aligned carbon nanofiber-based field emission electron sources with an integrated focusing electrode. J Vac Sci Technol B. 2004;22(1):35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fletcher BL, Hullander ED, Melechko AV, McKnight TE, Klein KL, Hensley DK, et al. Microarrays of biomimetic cells formed by the controlled synthesis of carbon nanofiber membranes. Nano Lett. 2004;4(10):1809–14. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fowlkes JD, Hullander ED, Fletcher BL, Retterer ST, Melechko AV, Hensley DK, et al. Molecular transport in a crowded volume created from vertically aligned carbon nanofibres: a fluorescence recovery after photobleaching study. Nanotechnology. 2006;17(22):5659–68. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/22/021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Melechko AV, Merkulov VI, Guillorn MA, Simpson ML, Lowndes DH, et al. Controlled transport of latex beads through vertically aligned carbon nanofiber membranes. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;81(1):135–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melechko AV, McKnight TE, Guillorn MA, Austin DW, Ilic B, Merkulov VI, et al. Nanopipe fabrication using vertically aligned carbon nanofiber templates. J Vac Sci Technol B. 2002;20(6):2730–3. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melechko AV, McKnight TE, Guillorn MA, Merkulov VI, Ilic B, Doktycz MJ, et al. Vertically aligned carbon nanofibers as sacrificial templates for nanofluidic structures. Appl Phys Lett. 2003;82(6):976–8. [Google Scholar]