Abstract

We previously showed that the tumor suppressor gene REIC/Dkk-3, when overexpressed by an adenovirus (Ad-REIC), exhibited a dramatic therapeutic effect on human cancers through a mechanism triggered by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Adenovirus vectors show no target cell specificity and thus may elicit unfavorable side effects through infection of normal cells even upon intra-tumoral injection. In this study, we examined possible effects of Ad-REIC on normal cells. We found that infection of normal human fibroblasts (NHF) did not cause apoptosis but induced production of interleukin (IL)-7. The induction was triggered by endoplasmic reticulum stress and mediated through IRE1α, ASK1, p38, and IRF-1. When Ad-REIC-infected NHF were transplanted in a mixture with untreated human prostate cancer cells, the growth of the cancer cells was significantly suppressed. Injection of an IL-7 antibody partially abrogated the suppressive effect of Ad-REIC-infected NHF. These results indicate that Ad-REIC has another arm against human cancer, an indirect host-mediated effect because of overproduction of IL-7 by mis-targeted NHF, in addition to its direct effect on cancer cells.

Cancer cells, like normal cells, cannot be free from regulation by other cells in the body (1). The microenvironment can exert both promotive and suppressive effects on malignant cells (2). The embryonic environment has been shown to suppress malignant phenotypes (3, 4), and this was recently indicated to be due to suppression of Nodal function by Lefty (5). Cells comprising cancer stroma in adult tissues are also involved in tumor suppression (6, 7). Mobilization of such potential tumor-suppressive effects of the microenvironment would provide an additional arm for cancer therapy (8).

Adenovirus vectors combined with appropriate cargo genes have great potential in cancer gene therapy because of their high infection efficiency and marginal genotoxicity (9). However, they show no target cell specificity and thus may also infect normal cells present in the surroundings of cancer cells. Provided that the interaction between cancer cells and normal cells is relevant to progression/suppression of cancer, it is critically important to understand not only cell autonomous phenomena in individual cell types infected by a therapeutic virus vector but also potential effects of the therapeutic virus vector on the composite system of interacting cell populations.

We have been studying the possible utility of an adenovirus vector carrying the tumor suppressor gene REIC/Dkk-3 (Ad-REIC) for gene therapy against human cancer. REIC/Dkk-3 was first identified as a gene that was down-regulated in association with immortalization of normal human fibroblasts (NHF)2 (10). Expression of REIC/Dkk-3 gene was shown to be reduced in many human cancer cells and tissues, including prostate cancer, renal clear cell carcinoma, testicular cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer (11–14), probably due to hypermethylation of the promoter (15). A single injection of Ad-REIC into tumors formed by transplantation of human prostate cancer cells (PC3 cells) into mice resulted in 4 of 5 mice becoming tumor-free (13). Subsequently, we found that Ad-REIC was effective also for human cancers derived from the testis, pleura, and breast (14, 16, 17). The potent multitargeting anti-cancer function of Ad-REIC shows great promise for clinical application, which will be shortly initiated.

REIC/Dkk-3 is a highly glycosylated secretory protein and is considered to physiologically act on cells via a yet-unidentified receptor. However, we found that the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells by Ad-REIC was because of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress loaded by overproduction of the REIC/Dkk-3 protein and that exogenously applied REIC/Dkk-3 protein showed no apoptosis inducing activity for cancer cells (13, 14). Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) was shown to be an essential step for the induction of apoptosis by Ad-REIC. ER stress is evoked by overload of unfolded/misfolded proteins in the ER, and eukaryotic cells respond to the threat by activating an unfolded protein response, i.e. attenuating de novo protein synthesis, promoting protein degradation by proteasomes, and inducing chaperone proteins to help proper folding of proteins (18). When ER stress remains at a level manageable by the unfolded protein response, cells can survive. On the other hand, overload of unfolded/misfolded protein beyond the cellular adoptive response leads to apoptotic cell death. Although Ad-REIC strongly induces apoptosis in many types of cancer cells, normal cells thus far examined are resistant to Ad-REIC-induced apoptosis despite expression of REIC/Dkk-3 at a level similar to that in cancer cells (13). The aim of this study was to determine the mechanisms of differential response of normal cells and cancer cells to Ad-REIC and to reveal the possible effect of Ad-REIC on a composite interacting system of normal cells and cancer cells. We found that Ad-REIC induced NHF to produce IL-7 via ER stress-triggered activation of p38. Furthermore, Ad-REIC-infected NHF significantly suppressed tumor growth of untreated PC3 cells transplanted in a mixture in vivo. These results mean that, in addition to its direct cancer cell-killing activity, Ad-REIC has another mechanism of action against human cancer, an indirect host-mediated effect because of overproduction of IL-7 by mis-targeted NHF.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Chemicals—The human prostate cancer cell line PC3 and the mouse colon cancer cell line Colon26 were cultivated in Ham's F-12 K medium and RPMI 1640 medium, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Normal human fibroblasts (OUMS-24), which were established and provided by Namba and co-workers (19), and primary mouse dermal fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco's modified minimum Eagle's medium (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) with 10% fetal bovine serum. REIC/Dkk-3 protein was purified from the conditioned medium of Ad-REIC-infected NHF by two-step ion-exchange column chromatography. p38 inhibitors (SB203580 and SC68376) and a protein kinase B/Akt inhibitor (Akt inhibitor) were purchased from Calbiochem. A JNK inhibitor (SP600125) and tunicamycin from Streptomyces sp. were purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and Sigma, respectively. Human recombinant IL-7, a neutralizing mouse-antibody against human IL-7, and mouse control IgG were from PeproTech EC (London, UK). Human recombinant IL-7 was purchased from PeproTech EC.

Adenovirus Vectors—REIC/Dkk-3 was overexpressed using an adenovirus (13). Ad-LacZ was used as a control.

Western Blot Analysis—Western blot analysis was performed under conventional conditions. Antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-human REIC/Dkk-3 antibody raised in our laboratory; mouse anti-β-galactosidase antibody (Calbiochem); rabbit anti-human IRF-1, rabbit anti-human stress-activated protein kinase/JNK, mouse anti-human phospho-stress-activated protein kinase/JNK (Thr-183/Tyr-185), rabbit anti-human c-Jun, rabbit anti-human phospho-c-Jun (Ser-63), rabbit anti-human phospho-STAT1 (Ser-727), rabbit anti-human phospho-STAT1 (Tyr-701), rabbit anti-human p38, rabbit anti human phospho-p38 (Thr-180/Tyr-182), rabbit anti-human ASK1, rabbit anti-human phospho-ASK1 (Thr-845), and rabbit anti-human IRE1α antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); rabbit anti-human phospho-IRE1α (Ser-724) antibody (ABR, Golden, CO); rabbit anti-human IRF-2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit anti-human STAT1 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); and mouse anti-human tubulin antibody (Sigma). The second antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Positive signals were detected by a chemiluminescence system (ECL plus, GE Healthcare).

Detection of IL-7 Production—Screening for cytokines produced by NHF infected with Ad-REIC was carried out by using RayBio® Human Cytokine Antibody Array VI and 6.1 (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA). NHF were infected with either Ad-LacZ or Ad-REIC (20 m.o.i.) and cultured for 48 h in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. The medium incubated for the last 24 h was used for the assay. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed using an assay kit (human IL-7 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit, RayBiotech).

Northern Blot Analysis—Twenty micrograms of total RNA isolated by the acid guanidinium thiocyanate/phenol-chloroform method was electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel and transferred to a Nytran Plus nylon membrane (GE Healthcare). A part of the human IL-7 gene (534-bp fragment) amplified by PCR using a primer set (forward, 5′-ATGTTCCATGTTTCTTTTAG-3′, and reverse, 3′-TCAGTGTTCTTTAGTGCCCA-5′) was used as a probe.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation—Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed under conventional conditions. In brief, cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde for cross-linking. Rabbit antibodies against human IRF-1 and IRF-2 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. To amplify the interferon regulatory factor-responsive region of the IL-7 promoter (381 bp; –539 to –158), a forward primer (5′-ACTTGTGGCTTCCGTGCACACATT-3′) and a reverse primer (3′-GACTGCAGTTTCATCCATCCCAAG-5′) were used.

Pulldown of Proteins Bound to the IL-7 Promoter in Vitro—Pulldown assay of proteins bound to the IL-7 promoter was performed under conditions reported previously (20). Briefly, the biotinylated genomic fragment (–1345 to –9) of the human IL-7 promoter was incubated with nuclear extracts and pulled down using streptavidin-agarose (Invitrogen). Bound proteins were determined by Western blot analysis.

RNA Interference—Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against human IRF-1 and Stat1 cDNAs (pre-designed siRNAs for IRF-1, numbers 115266 and 144970, and validated siRNA for Stat1, number 42860) and control siRNA (Silencer Negative control 2 siRNA) were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). IRE1α siRNA (siGENOME SMART pool M-004951) was purchased from Thermo Scientific Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). Transient transfection of siRNAs was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) 24 h prior to infection with Ad-LacZ or Ad-REIC.

Monitoring of Tumor Growth in Vivo—PC3 cells either alone or with NHF (5 × 106 cells each) were subcutaneously transplanted into male BALB/C nu/nu mice (SLC, Hamamatsu, Japan). The cells were infected with Ad-REIC or Ad-LacZ 24 h prior to transplantation at 20 m.o.i. The size of tumors was measured with a vernier caliper, and tumor volume was calculated as 1/2 × (shortest diameter)2 × (longest diameter). Anti-human IL-7 neutralizing antibody (0.5 mg) was intraperitoneally injected on day 0 (prior to cell transplantation) and on day 4. For the assay in immune competent mice, untreated Colon26 cells (4 × 106) mixed with dermal fibroblasts (4 × 106) infected with either Ad-LacZ or Ad-REIC at 100 m.o.i. were subcutaneously transplanted into 6-week-old female BALB/c mice.

For in vivo imaging of tumor growth, PC-3M-luc-C6 Bioware cells (PC3-luc; Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) and OUMS-24 cells were infected with either Ad-REIC or Ad-LacZ in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum 24 h prior to transplantation. A cell suspension (100 μl) containing 3 × 106 cells of each type was mixed with Matrigel (100 μl; BD Biosciences) and injected into the right flank subcutis of 8-week-old nude mice. Tumor size was monitored after injection with beetle luciferin potassium salt (Promega) using IVIS 2000 (Xenogen, Alameda, CA).

Assay of Splenic NK Cell Activity—Spleen cells were isolated from tumor-bearing nude mice, and NK cells were enriched using a mouse NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Cytotoxicity of NK cells to PC3 was determined using a Cytox96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega, Madison, WI) under conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the effector NK cells and the target PC3 cells (5,000 cells/well) were inoculated at ratios of 100:1, 50:1, 25:1, and 12.5:1 and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Activity of lactate dehydrogenase released from the cells was quantitated.

Statistical Analysis—Prior to statistical analysis, each experiment was repeated at least three times. The results are expressed as means ± S.D. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

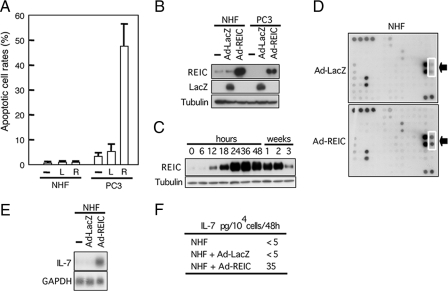

Induction of IL-7 in NHF by Infection with Ad-REIC—As reported previously (13), Ad-REIC efficiently induced apoptosis in PC3 cells (Fig. 1A). NHF did not undergo apoptosis but survived despite the fact that infection with Ad-REIC resulted in expression of REIC/Dkk-3 at a level similar to that in PC3 cells (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1A). Confluent NHF continuously overexpressed REIC/Dkk-3 protein for up to 2 weeks when infected with Ad-REIC (Fig. 1C). No gross alteration in morphology or behavior of NHF caused by Ad-REIC was noted.

FIGURE 1.

Infection with Ad-REIC-induced production of IL-7 but not apoptosis in NHF. A, apoptosis induced by infection with Ad-LacZ (L) or Ad-REIC (R) at 20 m.o.i. B, forced expression of REIC/Dkk-3 in NHF and PC3 cells by Ad-REIC infected at 20 m.o.i. determined by Western blot analysis. —, untreated. C, expression of REIC/Dkk-3 protein over a period of 2 weeks in confluent NHF infected with Ad-REIC at 20 m.o.i. D, screening for cytokines secreted into the medium by NHF infected with Ad-REIC using an antibody array. Dotted square indicates antibody against IL-7. E, induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC in NHF (24 h) demonstrated by Northern blot analysis. F, production of IL-7 by NHF infected with Ad-REIC in culture. Amounts of IL-7 were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay contained in the media of NHF uninfected, infected with Ad-LacZ, or infected with Ad-REIC at 20 m.o.i. incubated from 24 to 36 h after infection.

We screened for possible production of a humoral factor or factors by Ad-REIC-infected NHF. Application of a cytokine profiler array to the conditioned medium of Ad-REIC-infected NHF resulted in identification of IL-7 (Fig. 1D). Antibodies against other cytokines/growth factors carried by the array, including those against IL-1–6, -10, -13, -15, and -17, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ gave negative results. Infection of NHF with Ad-REIC induced IL-7 mRNA in culture (Fig. 1E). The infected NHF secreted IL-7 into the culture medium, ∼35 pg/ml/104 cells/48 h, whereas NHF infected with an adenovirus carrying LacZ (Ad-LacZ) produced no appreciable amount of IL-7 (Fig. 1F).

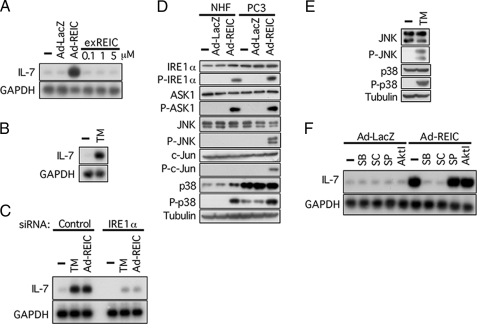

Induction of IL-7 in NHF by Ad-REIC Is Triggered by ER Stress and Mediated by ASK1 and p38—REIC/Dkk-3 is a secretory protein that is assumed to act on cells via a yet-unidentified cell surface receptor. On the other hand, we concluded from the results of previous work that apoptosis in Ad-REIC-infected cancer cells was triggered by ER stress (13, 14). As shown in Fig. 2A, infection of NHF with Ad-REIC induced IL-7 mRNA in culture, whereas exogenous REIC/Dkk-3 protein highly purified from the conditioned medium of NHF infected with Ad-REIC (supplemental Fig. S1B) showed no effect on IL-7 mRNA level, indicating that induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC depends on intracellular production of REIC/Dkk-3 and not on secreted REIC/Dkk-3 protein per se. In accordance with this, tunicamycin, a representative inducer of ER stress, induced IL-7 in NHF (Fig. 2B), and down-regulation of an ER stress sensor, IRE1α, resulted in complete abrogation of the induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC as well as tunicamycin (Fig. 2C). We therefore examined ER stress and its downstream pathway in NHF and PC3 cells.

FIGURE 2.

Signal transduction leading to induction of IL-7 in NHF infected with Ad-REIC. A, induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC in NHF demonstrated by Northern blot analysis. exREIC, exogenously added REIC/Dkk-3 protein purified from a conditioned medium of Ad-REIC-infected NHF. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. —, untreated. B, induction of IL-7 in NHF by tunicamycin (TM; 5 μg/ml, 24 h) demonstrated by Northern blot analysis. C, induction of IL-7 by tunicamycin or Ad-REIC was abrogated by down-regulation of an ER stress sensor, IRE1α. siRNAs were added 24 h prior to the application with tunicamycin or Ad-REIC. D, Western blot analysis for proteins involved in signal transduction triggered by Ad-REIC and leading to induction of IL-7. Cells were infected with Ad-REIC or Ad-LacZ at 20 m.o.i. for 36 h. E, Western blot analysis for proteins involved in signal transduction triggered by 5 μg/ml tunicamycin in NHF treated for 24 h. F, effects of kinase inhibitors on IL-7 induction. The inhibitors were added 1 h prior to infection with Ad-REIC. SB, SB-203580 (p38 inhibitor, 1 μm); SC, SC-68376 (p38 inhibitor, 10 μm); SP, SP600125 (JNK inhibitor, 100 nm); Akt I (Akt inhibitor, 10 μm).

IRE1α was activated in both NHF and PC3 cells upon infection with Ad-REIC (Fig. 2D). ASK1 was reported to be recruited to and phosphorylated by IRE1α on the ER membrane when cells suffer from ER stress (21). Activated ASK1, one of the MAPKKKs, in turn activates JNK and p38 by phosphorylation via MAPKK4/MAPKK7 and MAPKK3/MAPKK6, respectively. We therefore examined the functional state of the signal transduction pathway in Ad-REIC-infected NHK and PC3 cells. Activation of JNK, a hallmark for the induction of apoptosis by Ad-REIC (13, 14), was observed in PC3 cells but not in NHF as demonstrated by phosphorylation of JNK and its substrate c-Jun (Fig. 2D). Constitutive p38 level was higher in PC3 cells than in NHF. Infection with Ad-REIC induced phosphorylation of p38 in both cell types. Thus, infection with Ad-REIC provoked ER stress in a similar manner in NHF and PC3 cells at initial stages but resulted in distinct activation profiles of key stress-mediator MAPKs. In contrast to the effect of Ad-REIC, application of tunicamycin resulted in activation of both JNK and p38 in NHF (Fig. 2E). p38 inhibitors, SB203580 and SC68376, but not inhibitors for JNK and Akt, abrogated induction of IL-7 in NHF by Ad-REIC (Fig. 2F). These results indicate that activation of p38 is a critical event for the induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC.

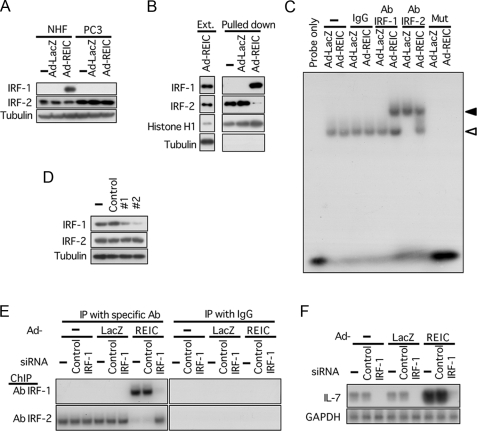

IRF-1 Is a Critical Transacting Factor for the Induction of IL-7 in NHF Infected with Ad-REIC—Although various types of cells have been shown to produce IL-7, little is known about the regulation of IL-7 gene expression (22). IRF-1 and IRF-2 are among a few transcription factors that have been reported to act on the IL-7 promoter in cells exposed to interferon-γ or ultraviolet light (23, 24). We therefore examined possible involvement of IRF-1 and IRF-2 in the induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC. IRF-1 was induced in NHF but not in PC3 cells by Ad-REIC, whereas IRF-2 was constitutively expressed in both types of cells (Fig. 3A). A pulldown assay for proteins bound to the IL-7 promoter resulted in identification of IRF-1 and IRF-2 (Fig. 3B). IRF-2 was fished with a probe of the IL-7 promoter in the nuclear extracts of untreated and Ad-LacZ-treated NHF, which was replaced by IRF-1 in the nuclear extract of Ad-REIC-infected NHF. This observation was corroborated by the results of an electromobility shift assay shown in Fig. 3C. The probe was supershifted by an IRF-1 antibody in NHF upon infection with Ad-REIC, whereas incubation with an IRF-2 antibody resulted in supershift of the probe in the control cells and in a partial shift down of the band in Ad-REIC-infected NHF, this probably due to binding of IRF-1 to the probe. Chromatin immunoprecipitation confirmed that the interaction of IRF-1 and IRF-2 on the IL-7 promoter took place in NHF in a manner similar to that observed in vitro (Fig. 3E). These results suggest involvement of IRF-1 in the induction of IL-7 triggered by ER stress on infection of NHF with Ad-REIC. To examine functional significance of the binding of IRF-1 on the promoter of IL-7, we applied siRNA of IRF-1 to NHF prior to Ad-REIC infection. The down-regulation of IRF-1 (Fig. 3D) not only abrogated induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC in NHF but also suppressed the constitutive low expression level of IL-7 (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that in nonstimulated NHF IRF-2 is constitutively expressed and negatively regulates the IL-7 gene by binding to the promoter and that IRF-1 is induced upon infection with Ad-REIC and activates the IL-7 gene by expelling IRF-2 from the IL-7 promoter.

FIGURE 3.

IRF-1 is a critical transacting factor for the induction of IL-7 in NHF infected with Ad-REIC. A, Western blot analysis for IRF-1 and IRF-2 in cells infected with Ad-LacZ or Ad-REIC at 20 m.o.i. —, untreated. B, pulldown assay of proteins bound to the IL-7 promoter in vitro using a biotinylated genomic fragment (–1345 to –9) of the human IL-7 promoter. Ext., nuclear extract. Contaminated tubulin was detected in the nuclear extract but not in the precipitates. C, electromobility shift assay for proteins binding to the human IL-7 promoter using nuclear extracts from NHF 36 h after infection. Mut, a mutated probe; white arrowhead, shifted bands; black arrowhead, supershifted bands observed with an anti-human IRF-1 or IRF-2 antibody (Ab). D, down-regulation of IRF-1 by siRNA. NHF were transfected with two different siRNAs (#1 (115266) and #2 (144970) for IRF-1). E, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay of the IL-7 promoter using either IRF-1 antibody or IRF-2 antibody in NHF transfected with siRNA for IRF-1 24 h prior to the infection. F, induction of IL-7 in NHF by Ad-REIC (20 m.o.i. for 36 h) was abrogated by down-regulation of IRF-1 using siRNA. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

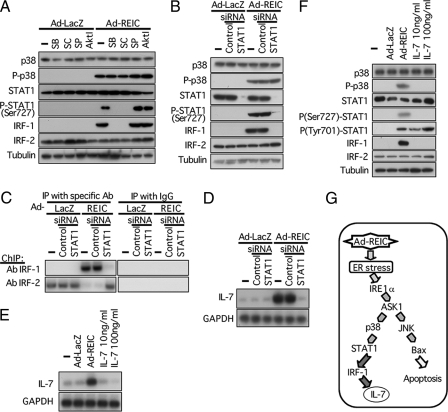

STAT1 Links p38 and IRF-1—The next question was how IRF-1 was induced in Ad-REIC-infected NHF. Li et al. (25) reported that STAT1 homodimer or STAT1/STAT2 heterodimer transcriptionally activated IRF-1 in cells exposed to interferon-α. On the other hand, STAT1 has been shown to be activated through phosphorylation by p38 (26). We therefore examined the possibility that STAT1 may link p38 and IRF-1 in the signal transduction pathway for the induction of IL-7 by Ad-REIC in NHF. Application of p38 inhibitors, SB203580 and SC68376, but not inhibitors for JNK and Akt, inhibited phosphorylation of STAT1 and induction of IRF-1 (Fig. 4A). SB203580 and SC68376 inhibit activity of p38, i.e. phosphorylation of p38 substrate proteins, but do not inhibit activation of p38, i.e. phosphorylation of p38 protein itself (supplemental Fig. S2C). In the present settings, phosphorylation of Ser-727 and not Tyr-701 of STAT1 is critical for the induction of IRF-1 (Fig. 4F). Down-regulation of STAT1 using siRNA resulted in abrogation of the induction of IRF-1, but not the activation of upstream p38, in NHF infected with Ad-REIC (Fig. 4B). The abortive induction of IRF-1 resulted in reoccupation of the IL-7 promoter by IRF-2 and eventually in abrogation of induction of IL-7 in NHF infected with Ad-REIC (Fig. 4, C and D). Exogenous IL-7 did not induce IL-7 itself nor activate the p38-STAT1-IRF-1 pathway (Fig. 4, E and F). These results collectively indicate that IL-7 was induced by Ad-REIC in NHF via the pathway summarized in Fig. 4G.

FIGURE 4.

STAT1 mediates from p38 to IRF-1 in the signal transduction leading to induction of IL-7. A, effects of kinase inhibitors on proteins involved in signal transduction triggered by Ad-REIC. The kinase inhibitors were applied under conditions described in the legend for Fig. 2F. P-STAT1 band was detected using an antibody against Ser-727-phosphorylated STAT1. SB, SB-203580; SC, SC-68376; SP, SP600125; Akt I Akt inhibitor. —, untreated. B, effect of STAT1 siRNA on proteins involved in signal transduction triggered by Ad-REIC. C, effect of STAT1 siRNA on binding of IRF-1 and IRF-2 to the IL-7 promoter demonstrated under conditions similar to those described in the legend for Fig. 3E. ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation (IP); Ab, antibody. D, induction of IL-7 in NHF by Ad-REIC was abrogated by down-regulation of STAT1 siRNA. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. E, exogenous IL-7 did not induce IL-7 as demonstrated by Northern blot analysis. F, exogenous IL-7 did not activate p38-STAT1-IRF-1 pathway as demonstrated by Western blot analysis. G, signal transduction pathway triggered by Ad-REIC leading to the induction of IL-7.

Suppression of Tumor Growth by NHF Infected with Ad-REIC—IL-7 is known to play a crucial role in development and survival of lymphocytes (22) and has been exploited for potential clinical application (27–29). Miller et al. (30) reported that IL-7-transduced dendritic cells evoked systemic immune responses and exerted a potent anti-tumor effect in a murine lung cancer model. We therefore examined the possible effect of infection of NHF with Ad-REIC on the composite interacting system of normal and cancer cells. When PC3 cells mixed with NHF pre-infected with Ad-REIC were transplanted into nude mice, growth of the PC3 cells was significantly suppressed compared with that in the case of transplantation of NHF infected with Ad-LacZ (Fig. 5A and supplemental Fig. S3A). Histological analysis of the tumors revealed decomposed tissue with degenerated PC3 cells when transplanted with Ad-REIC-infected NHF and a solid tissue packed with viable PC3 cells when transplanted with Ad-LacZ-infected NHF (Fig. 5B). The characteristics of tumor stoma cells may differ from those of normal human fibroblasts. We therefore performed an experiment similar to that shown in Fig. 5A using human lung cancer-associated cells and obtained similar results (supplemental Fig. S3B). The tumor-suppressive effect of Ad-REIC-infected normal mouse fibroblasts was also observed in immune-competent BALB/c mice into which syngeneic colon cancer cells (Colon26) had been transplanted (Fig. 5C and supplemental Fig. S3C). For monitoring the growth of the cancer cells specifically, we transplanted a mixture of NHF and PC3 cells transduced with the luciferase gene (PC3-luc) and observed them with IVIS 2000 (Fig. 5D). Partial suppression of tumor growth in vivo was observed when PC3-luc was infected with Ad-REIC at 1 m.o.i. prior to transplantation. Co-transplantation of PC3-luc with Ad-REIC-infected NHF (20 m.o.i.) synergistically suppressed the growth of PC3-luc compared with that with Ad-LacZ-infected NHF. On the other hand, co-cultivation of PC3 cells with Ad-REIC-infected NHF did not enhance apoptotic rate of PC3 cells (Fig. 6A, right panel), whereas infection of PC3 cells with Ad-REIC was confirmed to efficiently induce apoptosis in a cell-autonomous manner (Fig. 6, A, left panel, and C). Neither IL-7 nor recombinant REIC/Dkk-3 protein suppressed incorporation of [3H]thymidine (Fig. 6B). IL-7 did not induce apoptosis in PC3 cells in culture (Fig. 6C).

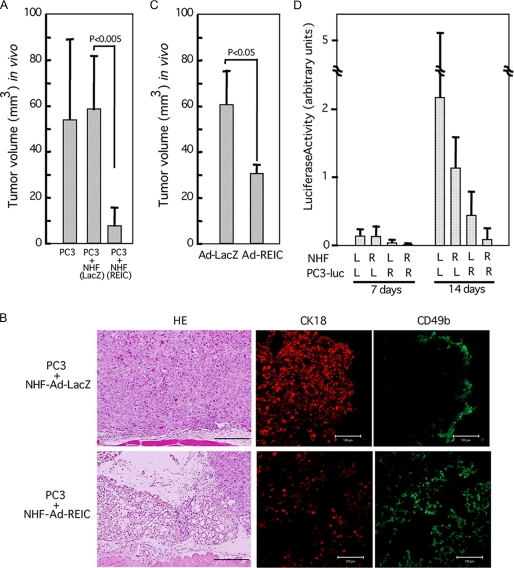

FIGURE 5.

Suppression of growth of untreated PC3 cells by co-transplanted NHF infected with Ad-REIC. A, quantitated volume of the tumors formed 14 days after transplantation into nude mice of 5 × 106 PC3 cells mixed with 5 × 106 NHF infected with Ad-LacZ or Ad-REIC at 20 m.o.i. B, histology of tumors described in A examined 14 days after transplantation. HE, hematoxylin-eosin staining. Cytokeratin K18 (CK18) (rabbit anti-human CK18 antibody; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and CD49b (fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD49b antibody; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) were used for identification of PC3 cells and mouse NK cells, respectively. Scale bars in hematoxylin-eosin-stained panels, 200 μm; scale bars in immunostained panels, 50 μm. C, indirect tumor-suppressive effect in BALB/c mice. Untreated Colon26 cells (4 × 106) mixed with dermal fibroblasts (4 × 106) infected with either Ad-LacZ or Ad-REIC at 100 m.o.i. were subcutaneously transplanted, and the sizes of tumors were determined 7 days after transplantation. D, synergistic tumor suppression because of direct and indirect effects of Ad-REIC. NHF (20 m.o.i.) and PC3-luc cells (1 m.o.i.) were infected with either Ad-REIC (R) or Ad-LacZ (L). Three million cells of each type were mixed and transplanted into nude mice. Observation was carried out with IVIS 2000 after injection of luciferin 7 and 14 days after transplantation.

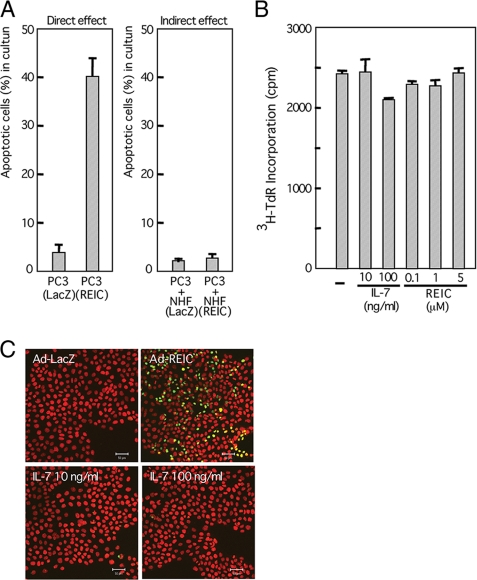

FIGURE 6.

Effect of Ad-REIC and IL-7 on NHF in culture. A, induction of apoptosis in PC3 cells in culture by direct infection of Ad-REIC (left panel) or by an indirect effect through the infected NHF (right panel). The indirect effect was examined after co-cultivating for 1 week. Numbers of cells undergoing apoptosis were estimated among cytokeratin-positive cells only. B, DNA synthesis of PC3 incubated with 1 μCi/ml [3H]thymidine for last 1 h during the culture period of 24 h. Neither IL-7 nor REIC/Dkk-3 protein exerted an inhibitory effect on DNA synthesis of PC3 in culture. C, induction of apoptosis by Ad-REIC (20 m.o.i., 36 h) but not by IL-7 (24 h) in PC3 cells in culture. Terminal dUTP nick-end labeling-positive cells are shown in green. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Involvement of IL-7 in Indirect Tumor-suppressive Effect of Ad-REIC—Finally, we examined whether IL-7 could mediate the indirect tumor-suppressive effect of Ad-REIC-infected NHF. Intraperitoneal injection of anti-IL-7 antibody (0.5 mg) on day 0 and day 4 partially restored the growth of PC3 cells transplanted with Ad-REIC-infected NHF determined on day 7 (Fig. 7A). NK-enriched cells isolated from spleens of nude mice bearing PC3 cells and Ad-REIC-infected NHF showed higher cytotoxicity to PC3 cells in vitro than did those from mice bearing PC3 cells and Ad-LacZ-infected NHF, and the elevated cytotoxicity was abrogated by injection of anti-IL-7 antibody (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that the indirect suppressive effect on growth of PC3 cells by Ad-REIC-infected NHF was at least partly due to induction of IL-7.

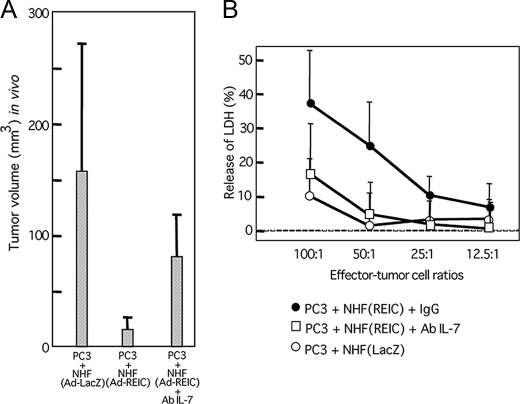

FIGURE 7.

Involvement of IL-7 in the indirect tumor-suppressive effect of Ad-REIC. A, abrogation of the suppressive effect of Ad-REIC-infected NHF on the growth of PC3 cells in vivo by intraperitoneal injection of an antibody (Ab) against IL-7 (0.5 mg). Transplantation was performed under conditions similar to those described in the legend of Fig. 5A. IL-7 antibody was injected on day 0 and day 4, and sizes of tumors were determined on day 7. B, cytotoxicity to PC3 cells exerted by NK-enriched spleen cells isolated from the nude mice described in the legend of A. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

DISCUSSION

The initial concept of using tumor suppressor genes in cancer gene therapy was that their delivery would correct or eradicate cancer cells defective in the corresponding tumor suppressor genes. The potent tumor-specific cell killing activity of Ad-REIC, however, depends on the triggering of ER stress and has nothing to do with the physiological function of REIC/Dkk-3 protein as indicated in this study and our previous studies (13, 14). An anti-cancer effect via ER stress has also been shown in gene therapy using mda-7/IL-24 (31). In addition to such cell-autonomous killing of cancer cells by the induction of ER stress, we showed in this study that ER stress evoked by Ad-REIC led to overproduction of IL-7 in NHF (Fig. 1).

Signal Transduction Linking ER Stress to Transcriptional Activation of IL-7—When cells are subjected to ER stress, TRAF2 is recruited to IRE1α, a sensor protein of ER stress, and TRAF2 in turn activates ASK1 (21). JNK and p38 are well known downstream kinases of ASK1. Infection of Ad-REIC resulted in activation of IRE1α and ASK1 in a similar manner both in NHF and in PC3 cells, but activation of JNK, which is an essential step for induction of apoptosis in cancer cells by Ad-REIC (13), was observed in PC3 cells and not in NHF (Fig. 2D). This is the critical step determining differential sensitivity to Ad-REIC between most cancer cells and normal cells, but mechanisms of the differential activation of MAPKs remain to be clarified.

ASK1 is thought to play a pivotal role in innate immunity in mammals. Activity of ASK1 was shown to be essential for lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of p38, which resulted in induction of cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α, in splenic cells, dendritic cells, and a macrophage cell line (32). Lipopolysaccharide acts on a cell surface receptor, Toll-like receptor 4. Because ASK1 is also activated in cells subjected to ER stress (Fig. 2D), it is conceivable that a certain immune response is evoked in cells upon ER stress. Although the biological significance of the ER stress-triggered activation of ASK1 is not well understood, it may contribute to elimination of pathogens such as viruses and bacteria by activating innate immunity. ER stress triggered by overload with excess viral protein synthesis may lead to apoptosis and inflammatory responses, eventually resulting in prevention of further spreading of the virus (33). ER stress was shown to induce interferon-β via XBP-1 in macrophages (34). The present finding that IL-7 was induced by ER stress and the fact that IL-7 plays nonredundant pleiotropic roles in development of both B cells and T cells, including the development of NK cells (22, 35), may lead to a better understanding of the relevance of ER stress to immune response.

Indirect Tumor Suppression by Ad-REIC-infected NHF—NHF infected with Ad-REIC suppressed the growth of untreated PC3 cells transplanted in a mixture into nude mice (Fig. 5). Similar suppression of tumor growth by Ad-REIC-infected NHF was observed in immune competent BALB/c mice into which syngeneic Colon26 cells had been transplanted (Fig. 5C and supplemental Fig. S3C). The indirect tumor-suppressive effect was not observed in culture (Fig. 6), indicating a host cell-mediated mechanism. Cytolytic activity of NK cells prepared from nude mice transplanted with Ad-REIC-infected NHF and PC3 cells was higher than that of NK cells prepared after transplantation with Ad-LacZ-infected NHF and PC3 cells (Fig. 7). It is known that athymic nude mice lacking development of T cells have higher cytotoxic activity of NK cells and macrophages than that in their euthymic counterparts (36). Injection of an antibody against IL-7 largely abrogated the suppression of the growth of PC3 cells by Ad-REIC-infected NHF as well as cytolytic activity of NK cells isolated from the transplanted mice (Fig. 7). These results indicate that IL-7 overproduced by ER stress activates innate immunity involving NK cells and eventually leads to suppression of tumor growth in vivo. We showed previously that a single injection of Ad-REIC into tumors formed by transplantation of PC3 cells into mice resulted in 4 of 5 mice becoming tumor-free (13). This was more efficient than had been expected considering that the infection efficiency of an adenovirus vector cannot be 100% in solid tumors in vivo. The efficient therapeutic effect, however, is conceivable when Ad-REIC has an additional non-cell autonomous mechanism for tumor suppression. We also showed that intratumoral injection of Ad-REIC resulted in suppression of local metastasis of a prostate cancer cell line in an orthotopic model (37). This may be due in part to an indirect effect via Ad-REIC-infected normal cells in the environment surrounding cancer cells.

Ad-REIC as a Bi-armed Therapeutic Agent—Although therapeutic trials using IL-7 against cancer have been carried out since the late 1990s, no major clinical responses have been reported thus far. This may be due in part to the advanced stages of the cancer cases (30, 38, 39), and activation of immune reaction against cancer by IL-7 only might not be strong enough to lead to massive killing of cancer cells. Our results show that the mis-targeted infection of cancer stroma cells by Ad-REIC activates the immune system through production of IL-7, whereas Ad-REIC infection of cancer cells results in a potent selective cell-autonomous killing function without immune suppression. This “one-bullet two-arms” finding may lead to a powerful new therapeutic approach to the treatment of human cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Eiichi Nakayama of Okayama University for critical discussion and Chika Taketa, an undergraduate student of Okayama University Medical School, for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by Grant 20015031 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to N. H.) and by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology (to H. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: NHF, normal human fibroblast; JNK, Jun N-terminal kinase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; m.o.i., multiplicity of infection; IL, interleukin; siRNA, small interfering RNA; MAPKK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; NK, natural killer.

References

- 1.Kenny, P. A., and Bissell, M. J. (2003) Int. J. Cancer 107 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller, M. M., and Fusenig, N. E. (2004) Nat. Rev. Cancer 4 839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mintz, B., and Illmensee, K. (1975) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72 3585–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoker, A. W., Hatier, C., and Bissell, M. J. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111 217–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Postovit, L. M., Margaryan, N. V., Seftor, E. A., Kirschmann, D. A., Lipavsky, A., Wheaton, W. W., Abbott, D. E., Seftor, R. E., and Hendrix, M. J. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 4329–4334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhowmick, N. A., Chytil, A., Plieth, D., Gorska, A. E., Dumont, N., Shappell, S., Washington, M. K., Neilson, E. G., and Moses, H. L. (2004) Science 303 848–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, B. G., Li, C., Qiao, W., Mamura, M., Kasprzak, B., Anver, M., Wolfraim, L., Hong, S., Mushinski, E., Potter, M., Kim, S. J., Fu, X. Y., Deng, C., and Letterio, J. J. (2006) Nature 441 1015–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenny, P. A., Lee, G. Y., and Bissell, M. J. (2007) Front. Biosci. 12 3468–3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rein, D. T., Breidenbach, M., and Curiel, D. T. (2006) Future Oncol. 2 137–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuji, T., Miyazaki, M., Sakaguchi, M., Inoue, Y., and Namba, M. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268 20–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nozaki, I., Tsuji, T., Iijima, O., Ohmura, Y., Andou, A., Miyazaki, M., Shimizu, N., and Namba, M. (2001) Int. J. Oncol. 19 117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurose, K., Sakaguchi, M., Nasu, Y., Ebara, S., Kaku, H., Kariyama, R., Arao, Y., Miyazaki, M., Tsushima, T., Namba, M., Kumon, H., and Huh, N. H. (2004) J. Urol. 171 1314–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abarzua, F., Sakaguchi, M., Takaishi, M., Nasu, Y., Kurose, K., Ebara, S., Miyazaki, M., Namba, M., Kumon, H., and Huh, N. H. (2005) Cancer Res. 65 9617–9622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanimoto, R., Abarzua, F., Sakaguchi, M., Takaishi, M., Nasu, Y., Kumon, H., and Huh, N. H. (2007) Int. J. Mol. Med. 19 363–368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi, K., Ouchida, M., Tsuji, T., Hanafusa, H., Miyazaki, M., Namba, M., Shimizu, N., and Shimizu, K. (2002) Gene (Amst.) 282 151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawasaki, K., Watanabe, M., Sakaguchi, M., Ogasawara, Y., Ochiai, K., Nasu, Y., Doihara, H., Kashiwakura, Y., Huh, N. H., Kumon, H., and Date, H. (2009) Cancer Gene Ther. 16 65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashiwakura, Y., Ochiai, K., Watanabe, M., Abarzua, F., Sakaguchi, M., Takaoka, M., Tanimoto, R., Nasu, Y., Huh, N. H., and Kumon, H. (2008) Cancer Res. 68 8333–8341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, C., Bailly-Maitre, B., and Reed, J. C. (2005) J. Clin. Investig. 115 2656–2664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai, L., Mihara, K., Kondo, Y., Honma, M., and Namba, M. (1993) Int. J. Cancer 53 451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaguchi, M., Sonegawa, H., Murata, H., Kitazoe, M., Futami, J., Kataoka, K., Yamada, H., and Huh, N. H. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19 78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekine, Y., Takeda, K., and Ichijo, H. (2006) Curr. Mol. Med. 6 87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang, Q., Li, W. Q., Aiello, F. B., Mazzucchelli, R., Asefa, B., Khaled, A. R., and Durum, S. K. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 513–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aragane, Y., Schwarz, A., Luger, T. A., Ariizumi, K., Takashima, A., and Schwarz, T. (1997) J. Immunol. 158 5393–5399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oshima, S., Nakamura, T., Namiki, S., Okada, E., Tsuchiya, K., Okamoto, R., Yamazaki, M., Yokota, T., Aida, M., Yamaguchi, Y., Kanai, T., Handa, H., and Watanabe, M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 6298–6310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, X., Leung, S., Qureshi, S., Darnell, J. E., Jr., and Stark, G. R. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 5790–5794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gollob, J. A., Schnipper, C. P., Murphy, E. A., Ritz, J., and Frank, D. A. (1999) J. Immunol. 162 4472–4481 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wittig, B., Marten, A., Dorbic, T., Weineck, S., Min, H., Niemitz, S., Trojaneck, B., Flieger, D., Kruopis, S., Albers, A., Loffel, J., Neubauer, A., Albers, P., Muller, S., Sauerbruch, T., Bieber, T., Huhn, D., and Schmidt-Wolf, I. G. (2001) Hum. Gene Ther. 12 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fry, T. J., and Mackall, C. L. (2002) Blood 99 3892–3904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sportes, C., and Gress, R. E. (2007) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 601 321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, P. W., Sharma, S., Stolina, M., Butterfield, L. H., Luo, J., Lin, Y., Dohadwala, M., Batra, R. K., Wu, L., Economou, J. S., and Dubinett, S. M. (2000) Hum. Gene Ther. 11 53–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauane, M., Lebedeva, I. V., Su, Z. Z., Choo, H. T., Randolph, A., Valerie, K., Dent, P., Gopalkrishnan, R. V., and Fisher, P. B. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 2988–2993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuzawa, A., Saegusa, K., Noguchi, T., Sadamitsu, C., Nishitoh, H., Nagai, S., Koyasu, S., Matsumoto, K., Takeda, K., and Ichijo, H. (2005) Nat. Immunol. 6 587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He, B. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13 393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith, J. A., Turner, M. J., DeLay, M. L., Klenk, E. I., Sowders, D. P., and Colbert, R. A. (2008) Eur. J. Immunol. 38 1194–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vosshenrich, C. A., Garcia-Ojeda, M. E., Samson-Villeger, S. I., Pasqualetto, V., Enault, L., Richard-Le Goff, O., Corcuff, E., Guy-Grand, D., Rocha, B., Cumano, A., Rogge, L., Ezine, S., and Di Santo, J. P. (2006) Nat. Immunol. 7 1217–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Budzynski, W., and Radzikowski, C. (1994) Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 16 319–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edamura, K., Nasu, Y., Takaishi, M., Kobayashi, T., Abarzua, F., Sakaguchi, M., Kashiwakura, Y., Ebara, S., Saika, T., Watanabe, M., Huh, N. H., and Kumon, H. (2007) Cancer Gene Ther. 14 765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fricker, J. (1996) Mol. Med. Today 2 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, L. X., Li, R., Yang, G., Lim, M., O'Hara, A., Chu, Y., Fox, B. A., Restifo, N. P., Urba, W. J., and Hu, H. M. (2005) Cancer Res. 65 10569–10577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.