Abstract

Parkinson disease (PD)-associated genomic deletions and the destabilizing L166P point mutation lead to loss of the cytoprotective DJ-1 protein. The effects of other PD-associated point mutations are less clear. Here we demonstrate that the M26I mutation reduces DJ-1 expression, particularly in a null background (knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts). Thus, homozygous M26I mutation causes loss of DJ-1 protein. To determine the cellular consequences, we measured suppression of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and cytotoxicity for [M26I]DJ-1, and systematically all other DJ-1 methionine and cysteine mutants. C106A mutation of the central redox site specifically abolished binding to ASK1 and the cytoprotective activity of DJ-1. DJ-1 was apparently recruited into the ASK1 signalosome via Cys-106-linked mixed disulfides. The designed higher order oxidation mimicking [C106DD]DJ-1 non-covalently bound to ASK1 even in the absence of hydrogen peroxide and conferred partial cytoprotection. Interestingly, mutations of peripheral redox sites (C46A and C53A) and M26I also led to constitutive ASK1 binding. Cytoprotective [wt]DJ-1 bound to the ASK1 N terminus (which is known to bind another negative regulator, thioredoxin 1), whereas [M26I]DJ-1 bound to aberrant C-terminal site(s). Consequently, the peripheral cysteine mutants retained cytoprotective activity, whereas the PD-associated mutant [M26I]DJ-1 failed to suppress ASK1 activity and nuclear export of the death domain-associated protein Daxx and did not promote cytoprotection. Thus, cytoprotective binding of DJ-1 to ASK1 depends on the central redox-sensitive Cys-106 and may be modulated by peripheral cysteine residues. We suggest that impairments in oxidative conformation changes of DJ-1 might contribute to PD neurodegeneration.

Loss-of-function mutations in the DJ-1 gene (PARK7) cause autosomal-recessive hereditary Parkinson disease (PD)2 (1). The most dramatic PD-associated mutation L166P impairs DJ-1 dimer formation and dramatically destabilizes the protein (2–7). Other mutations such as M26I (8) and E64D (9) have more subtle defects with unclear cellular consequences (4, 7, 10, 11). In addition to this genetic association, DJ-1 is neuropathologically linked to PD. DJ-1 is up-regulated in reactive astrocytes, and it is oxidatively modified in brains of sporadic PD patients (12–14).

DJ-1 protects against oxidative stress and mitochondrial toxins in cell culture (15–17) as well as in diverse animal models (18–21). The cytoprotective effects of DJ-1 may be stimulated by oxidation and mediated by molecular chaperoning (22, 23), and/or facilitation of the pro-survival Akt and suppression of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) pathways (6, 24, 25). The cytoprotective activity of DJ-1 against oxidative stress depends on its cysteine residues (15, 17, 26). Among the three cysteine residues of DJ-1, the most prominent one is the easiest oxidizable Cys-106 (27) that is in a constrained conformation (28), but the other cysteine residues Cys-46 and Cys-53 have been implicated with DJ-1 activity as well (22). However, the molecular basis of oxidation-mediated cytoprotective activity of DJ-1 is not clear. Moreover, the roles of PD-mutated and in vivo oxidized methionines are not known.

Here we have mutagenized all oxidizable residues within DJ-1 and studied the effects on protein stability and function. The PD-associated mutation M26I within the DJ-1 dimer interface selectively reduced protein expression as well as ASK1 suppression and cytoprotective activity in oxidatively stressed cells. These cell culture results support a pathogenic effect of the clinical M26I mutation (8). Furthermore, oxidation-defective C106A mutation abolished binding to ASK1 and cytoprotective activity of DJ-1, whereas the designed higher order oxidation mimicking mutant [C106DD]DJ-1 bound to ASK1 even in the absence of H2O2 and conferred partial cytoprotection. The peripheral cysteine mutants [C46A]DJ-1 and [C53A]DJ-1 were also cytoprotective and were incorporated into the ASK1 signalosome even in the basal state. Thus, DJ-1 may be activated by a complex mechanism, which depends on the redox center Cys-106 and is modulated by the peripheral cysteine residues. Impairments of oxidative DJ-1 activation might contribute to the pathogenesis of PD.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Display—The atom coordinates of the DJ-1 dimer crystal structure (29) were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 1PDW) and visualized with MacPyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC).

Site-directed Mutagenesis—[wt]DJ-1/V5/HIS plasmid (10) was used as template for two independent PCR reactions with the following primer pairs: forward mutagenesis primer (supplemental Table S1) and BamHI-Stop reverse primer: 5′-ATCTGGATCCGTCTTTAAGAACAAGTGGAGCC-3′ and for the second PCR reverse mutagenesis primer (supplemental Table S1) and NcoI forward primer: 5′-AACCATGGGAATGGCTTCCAAAAGAGCTCTG-3′. These two PCR products were then used as templates for a PCR using the above outer primers and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen), yielding DJ-1/V5 constructs. The [C106A]DJ-1/V5 construct was used as a template to introduce the C53A mutation by the same strategy, yielding the double mutant [C53A/C106A]DJ-1/V5, and sequential introduction of C46S and C53S (mutagenesis primers; supplemental Table S1) yielded the tripleC mutant [C46S/C53S/C106A]DJ-1/V5.

The DJ-1/V5 constructs were used as templates for PCRs with EcoRI forward primer: 5′-ACGAATTCGAATGGCTTCCAAAAGAGCTCTGGT-3′ and NotI reverse primer 5′-AGCGGCCGCGTCTTTAAGAACAAGTGGAGCC-3′, and subcloned into pCMV-Myc (Clontech), yielding Myc/DJ-1 constructs, and PCR products produced with NheI forward primer 5′-CGCTAGCATGGCTTCCAAAAGAGCTCTGG-3′ and EcoRI reverse primer 5′-CGAATTCCTAGTCTTTAAGAACAAGTGGAGCCTTC-3′ were subcloned into pIRES2 (Clontech) to generate bicistronic constructs expressing untagged DJ-1 and ZsGreen1 fluorescent protein or into pcDNA3.1/Zeo (Invitrogen) yielding untagged stable expression vectors.

To introduce oxidation-mimicking Cys-106 mutations, the Myc/[wt]DJ-1 construct was used as a template for two independent PCR reactions with the following primer pairs: forward mutagenesis primer (supplemental Table S1) and NotI reverse primer (see above) and for the second PCR reverse mutagenesis primer (supplemental Table S1) and EcoRI forward primer (see above). These two PCR products were then used as templates for a PCR using the above outer primers and subcloned into pCMV-Myc. To create HA-tagged constructs the Myc-tagged constructs were digested with EcoR1 and Not1 and subcloned into pCMV-HA (Clontech).

All constructs were sequence confirmed using BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer using 500 ng of plasmid as a template. Reaction products were analyzed using an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Generation of Stably Back-transfected DJ-1 MEF Cell Lines—DJ-1–/– MEFs were transfected with the pcDNA3.1/Zeo constructs containing wt and mutant DJ-1 or empty vector, using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Stable transfectants were selected and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 400 μg/ml Zeocin (Invivogen).

Determination of DJ-1 Protein Levels—HEK293 and DJ-1–/– MEF cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum without antibiotics. Transient transfections were performed with FuGENE 6, and 2 days later cells were lysed in 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Protein content in the lysates was determined with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay. After denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis proteins were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences Hybond-P).

DJ-1 was detected on Western blots with mouse monoclonal antibodies against the epitope tags, anti-V5 (Invitrogen) and 9E10 anti-Myc (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA), and with rabbit polyclonal antiserum 3407 (6). Equal loading was confirmed by reprobing blots with anti-β-actin or anti-α-tubulin (both from Sigma). Secondary antibodies used were peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Dianova). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (Immobilon Western HRP substrate, Millipore).

Determination of DJ-1 mRNA Levels—Total RNA was purified from transfected cells with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using Transcriptor RT and oligo-dT primers (Roche Applied Science). The resulting cDNAs were PCR-amplified using EcoRI forward primer in combination with NotI reverse primer (see above). For normalization, β-actin mRNA was amplified in parallel using β-actin-fwd (5′-CTAAGGCCAACCGTGAA-3′) and β-actin-rev (5′-CCGGAGTCCATCACAAT-3′) primers. Amplification rates were linear at 25 cycles, as visualized on ethidium bromide-stained 1.2% agarose gels. Bands were detected with a Vilber Lourmat (Vilber, Marne La Vallee, France) and quantified using ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences).

Measurement of DJ-1 Protein Stability—HEK293E and DJ-1–/– MEF cells were transiently transfected as described above. One day after transfection the cells were starved for 1 h in methionine/cysteine-free DMEM (Invitrogen) plus 1% l-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. They were then pulsed for 3 h with 14.4 μCi/ml [35S]methionine/[35S]cysteine (Promix, Amersham Biosciences), rinsed, and chased with DMEM (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) plus 1% l-glutamine, 1 mm l-cysteine, 1 mm l-methionine, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were lysed in 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris (pH 7.6) plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture, and immunoprecipitation was performed with monoclonal anti-Myc-agarose (Sigma) or anti-DJ-1 (Alphagenix) followed by protein A-Sepharose (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY). After denaturing 15% PAGE, the gels were fixed, soaked in Amplify (Amersham Biosciences), and dried. The radiolabeled proteins were visualized on Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham Biosciences). Band densities were quantified using the ImageQuant program (Amersham Biosciences). Band intensities of the different time points were expressed as percentage to the DJ-1 band intensity at time point zero. Half-life times were calculated by curve fitting assuming an exponential decay rate (x = e–kt).

Dimerization of DJ-1—HEK293T cells were transiently co-transfected with Myc-tagged and HA-tagged DJ-1 constructs using Lipofectamine 2000. After 30 h, cells were lysed in 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris (pH 7.6) plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture. Lysates were incubated for 1 h with anti-Myc-agarose affinity gel (Sigma). Immunoprecipitates were subjected to denaturing 15% PAGE and Western transfer, and blots were probed with 9E10 monoclonal anti-Myc and 3F10 monoclonal anti-HA (Roche Applied Science).

ASK1 Co-immunoprecipitations—HEK293E cells were transiently co-transfected with constructs encoding full-length or truncated ASK1 lacking the N-terminal 648 amino acids [ΔN]ASK1 fused to a C-terminal HA tag (30) together with Myc/DJ-1 constructs, and cultured for 36 h in the continued absence of antibiotics to minimize the basal cellular stress. Then cells were exposed to 1 mm H2O2 and lysed in 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm KCl, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture. Immunoprecipitation was performed with monoclonal anti-HA-agarose (Sigma). Samples were electrophoresed through 4–20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen). For non-denaturing SDS-PAGE, samples were boiled in Laemmli buffer lacking the reducing agent β-mercaptoethanol and separated on continuous 6% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Corresponding Western blots were sequentially probed with polyclonal anti-ASK1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and monoclonal antibodies 9E10 anti-Myc or 3E8 anti-DJ-1 (Stressgen, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada).

Size Exclusion Chromatography of the ASK1 Complex—HEK293E cells were transiently co-transfected with full-length ASK1/HA together with Myc/DJ-1 constructs, and cultured for 36 h in the continued absence of antibiotics to minimize the basal cellular stress. Then cells were exposed to 1 mm H2O2 for 30 min and lysed in 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm KCl, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture. Lysates were cleared by filtration through a 0.22-μm filter (Millipore). Equal amounts of protein in a total volume of 2 ml were loaded onto a Sephacryl S-500 16/60 column pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. The proteins were eluted at 0.8 ml/min, and 1.5-ml fractions were collected.

ASK1 Immune Complex Kinase Assay—Stable back-transfectant MEF cell lines were incubated for 30 min in serum- and pyruvate-free medium with or without 500 μm H2O2. They were washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm KCl, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) plus Complete protease inhibitor mixture. Immunoprecipitation was performed with ASK1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by protein A-Sepharose overnight. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with lysis buffer and once with kinase buffer (Cell Signaling). Beads were resuspended in 50 μl of kinase buffer containing 200 μm ATP, 0.2 μg/μl myelin basic protein, and 0.1 μCi/μl[γ-32P]ATP. After 20-min incubation at 30 °C, the reaction was stopped with 6× Laemmli buffer. Samples were heated at 95 °C for 15 min and loaded on a denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie Blue, dried, and the radioactive proteins were visualized on Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham Biosciences).

Measurement of Cytotoxicity—Immortalized DJ-1–/– MEF cells were transfected with Myc/DJ-1 expression constructs using FuGENE 6. Untagged DJ-1 stably re-transfected MEF cell lines were analyzed without previous transfection. Cytotoxicity after exposure to H2O2 was determined with the CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI), as previously described (6). Cytotoxicity was quantified as the percentage of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity released into the medium supernatant relative to total LDH activity in the medium plus cells, as measured after direct lysis of the experimental well contents with Triton X-100.

Daxx Translocation—Stably back-transfected DJ-1–/– MEF cell lines were transfected with pRK5-FLAG-Daxx using FuGENE 6. One day after transfection cells were seeded on coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (Sigma) and collagen (type 1, Upstate Biotechnology). After another 24 h cells were incubated for 30 min in serum- and pyruvate-free medium with or without 500 μm H2O2. Cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. After permeabilization with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, cells were blocked in 10% goat serum in PBS and subsequently incubated with mouse anti-FLAG (Sigma) followed by anti-mouse Alexa568 (Molecular Probes) in 1% bovine serum/PBS for 1 h. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes). Pictures were taken with an Axiovert 200M fluorescent microscope (Zeiss) using 20× objective. For each condition 300 randomly taken pictures were analyzed. The number of cells with nuclear and cytosolic Daxx was counted, and the ratio of cytosolic Daxx versus total number of transfected cells calculated.

Statistical Analyses—Each experiment was performed independently at least two times. The results shown in figures are, if not otherwise stated, mean values ± S.E. of 2–4 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance with Bonferroni multiple comparisons post test using InStat (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Mutagenesis of DJ-1 Cysteine and Methionine Residues—Human DJ-1 contains 3 cysteines and 5 methionines (including the start methionine), all of which are highly conserved (supplemental Fig. S1). The easily oxidizable Cys-106 is in a strained backbone conformation within the putative active site of DJ-1 (28, 29, 31) and is perfectly conserved in DJ-1 proteins of all organisms. Cys-106 was mutagenized to alanine to generate a mutant without an oxidizable side chain. Conversely, we introduced increasing negative charge to simulate Cys-106 oxidation states (sulfenic, sulfinic, and sulfonic acid) by mutagenesis to 1–3 acidic residues, aspartate and glutamate. Cys-106 resides in the center of the DJ-1 crystal structure, whereas the other two cysteines are located more peripherally (supplemental Fig. S1). Cys-46 is strictly conserved in eukaryotes and Cys-53 is conserved in vertebrates. We mutagenized both these cysteines to alanine and generated the double mutant C106A/C53A and C106A/C53S/C46S (tripleC).

As for the methionines, the highly conserved eukaryotic Met-17 is critically engaged in the DJ-1 dimer interface (31). Met-26 is conserved in vertebrates, and a homozygous M26I missense mutation was identified in an Ashkenazi Jewish patient (8). Finally, Met-133 and Met-134 are conserved only in higher vertebrates but were both specifically oxidized in PD brain samples (13). Here we mutagenized every one of these methionines to the non-oxidizable isoleucine.

Mutations C46A and M26I in the Dimer Interface Destabilize the DJ-1 Protein—To determine the effects of cysteine and methionine mutations on DJ-1 protein stability, we measured steady-state protein levels in transiently transfected cells (Fig. 1, A–D). Irrespective of position and nature of the tag, there was no reduction of protein levels for the Cys-53 and Cys-106 mutants alone and in combination (Fig. 1, A and B). In contrast, the levels of [C46A]DJ-1 were reduced, and a similar reduction was observed for the tripleC mutant (Fig. 1, A and B), irrespective of sequence and position of the terminal epitope tag. These findings suggest that Cys-46 in the dimer interface is important for protein stability, most likely by mediating dimerization (32).

FIGURE 1.

Expression of DJ-1 cysteine and methionine mutants. A and B, DJ-1 cysteine mutants with C-terminal V5 tag were transiently transfected in HEK293T cells (A) and with N-terminal Myc tag or vector control in HEK293E cells (B). Western blots from whole cell lysates were concomitantly reacted with anti-V5 and the protein loading control anti-β-actin (A) and with anti-Myc and anti-α-tubulin (B), respectively. Molecular weight markers are indicated to the left. C, the indicated N-terminally Myc-tagged DJ-1 constructs (lanes 1–5) or vector control (lane 6) were transiently transfected in HEK293E cells. Western blots from whole cell lysates were reacted with anti-Myc (top panel). Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-DJ-1 (middle panel), the upper arrowhead points to the transfected, tagged DJ-1, and the lower arrowhead to the endogenous DJ-1. Equal protein loading was confirmed by reprobing the blot with anti-α-tubulin (bottom panel). D, the indicated DJ-1 variants fused to N-terminal Myc tag (lanes 1–5), C-terminal V5 tag (lanes 7 and 8), or without epitope tag (lanes 10 and 11), and the respective vector controls (lanes 6, 9, and 12) were transiently transfected into DJ-1–/– MEF cells. DJ-1 on Western blots from whole cell lysates was detected with anti-Myc (lanes 1–6, top panel) or anti-V5 (lanes 7–9, top panel), and anti-DJ-1 (middle panels). Even loading was confirmed by reprobing with anti-α-tubulin (bottom panels). E, total RNA was extracted from DJ-1–/– MEF cells transiently transfected with Myc/[wt]DJ-1, Myc/[M26I]DJ-1, and pCMV vector plasmid. After reverse transcription, cDNA samples were amplified by PCR using primers specific for Myc/DJ-1 (upper panel) or β-actin (lower panel), and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis followed by ethidium bromide staining. F, DJ-1–/– MEF cells were transiently transfected with the indicated DJ-1 constructs or vector controls. Reverse transcription-PCR analysis was performed as above, and the relative expression of DJ-1 mRNA of the various constructs was determined. There were no significant differences in mRNA expression of the reduced-protein mutants [M26I]DJ-1 and [C46A]DJ-1 compared with [wt]DJ-1, although the overall expression levels driven by pCDNA were lower than the other two mammalian expression vectors.

Isoleucine substitutions of Met-133 and Met-134 did not affect DJ-1 protein levels at all, and the conservative M17I mutation in the dimer interface also did not reduce DJ-1 protein levels (Fig. 1, C and D). Interestingly, the PD-associated M26I mutant DJ-1 was variably expressed in human embryonic kidney HEK293E cells, and particularly reduced when expressed as N-terminally Myc-tagged construct (Fig. 1C). In this experimental system, endogenous wild-type [wt]DJ-1 is co-expressed with mutant DJ-1 in a heterozygous state, which may stabilize mutants with subtle structural defects. However, the affected PD patient was homozygous for the M26I mutation (8). Thus, we investigated expression levels of [M26I]DJ-1 in a cell system devoid of potentially stabilizing endogenous DJ-1 homomers. In DJ-1 knockout MEF cells (6), steady-state levels of [M26I]DJ-1 protein were clearly reduced. Again [M26I]DJ-1 was particularly poorly expressed when fused to an N-terminal Myc tag, but also C-terminal V5-tagged and untagged variants were affected by the M26I mutation (Fig. 1D). The observed reductions of Myc/[M26I]DJ-1 protein levels were not due to reduced mRNA expression, as revealed by semi-quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (Fig. 1, E and F).

The above steady-state expression level measurements of DJ-1 mutant protein and mRNA indicated a destabilization mediated by the M26I and C46A mutations. To directly demonstrate protein destabilization of Myc/[M26I]DJ-1 and Myc/[C46A]DJ-1, quantitative pulse-chase experiments were performed. Myc/[wt]DJ-1 is a stable protein with a half-life time of ∼15 h both in HEK293E cells and DJ-1–/– MEFs (supplemental Fig. S2). In contrast, the decay of both Myc/[M26I]DJ-1 and Myc/[C46A]DJ-1 was greatly accelerated. The C46A mutation in the dimer interface reduced the half-life time of DJ-1 to ∼2 h in both cell types. The PD-associated M26I mutation reduced the half-life time to 2.6 ± 0.6 h in HEK293E cells and even further down to 1.9 ± 0.1 h in MEF cells lacking endogenous DJ-1 (supplemental Fig. S2). Thus, the reduced steady-state level of the dimer interface mutant [C46A]DJ-1 is due to dramatically accelerated protein degradation. Similarly, the PD-associated [M26I]DJ-1 mutant has reduced protein stability, which is particularly evident in MEF cells lacking potentially stabilizing endogenous [wt]DJ-1 homomers.

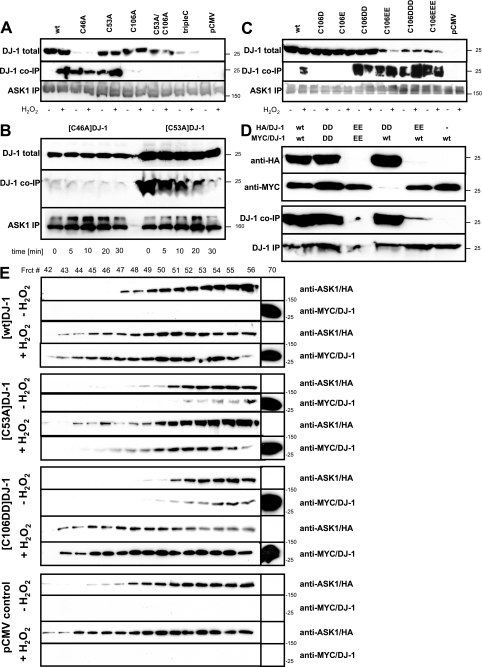

H2O2-dependent DJ-1 Interaction with ASK1 Is Mediated by the Central Cys-106 and Modulated by the Peripheral Cysteines—DJ-1 is conserved even in Escherichia coli, where it protects against multiple stresses by an unknown mechanism (33). Although E. coli does not have an ASK1 equivalent, DJ-1 may promote at least some of its cytoprotective functions in mammalian cells by suppressing ASK1 (6, 24). We found that DJ-1 directly binds to ASK1 in oxidatively stressed cells. To determine which of the oxidizable residues are responsible for this effect, we co-transfected HEK293E cells with Myc/DJ-1 mutants and ASK1/HA. As expected, Myc/[wt]DJ-1 co-immunoprecipitated with ASK1/HA only after H2O2 exposure (Fig. 2A). Alanine mutations of the peripheral cysteine residues did not prevent DJ-1 binding to ASK1. Surprisingly, Myc/[C53A]DJ-1 and even the less stable Myc/[C46A]DJ-1 co-immunoprecipitated with ASK1/HA after control medium change without H2O2 (Fig. 2A). The almost wt ASK1-binding capacity even of the poorly expressed peripheral mutant [C46A]DJ-1 is very remarkable, suggesting a high affinity. To study the kinetics of the DJ-1-ASK1 interaction we estimated the off-rate. HEK293E cells were briefly (3 min) exposed to 1 mm H2O2 followed by replacement with fresh medium. After defined time points, cells were lysed and ASK1/HA co-immunoprecipitations with DJ-1 performed. The constitutively binding mutants [C46A]DJ-1 and [C53A]DJ-1 showed a relatively slow dissociation from ASK1/HA after H2O2 washout (Fig. 2B) compared with the very rapid (<5 min after washout) dissociation of [wt]DJ-1 from ASK1/HA (see Fig. 4B). Thus, the enhanced steady-state ASK1 binding of the peripheral DJ-1 mutants is due to a considerable part to a slower off-rate.

FIGURE 2.

Influence of cysteine mutations on ASK1 binding and DJ-1 dimerization. A–C, HEK293E cells were co-transfected with ASK1/HA together with the indicated N-terminal Myc-tagged DJ-1 cysteine mutant constructs, along with pCMV vector controls. After 36-h culturing, the cells were treated for 30 min without (–) or with (+) 1 mm H2O2 and lysed directly (A and C), or treated for 30 min with 1 mm H2O2 followed by replacement with fresh medium for the indicated times (B). Then cells were lysed and direct Western blots prepared for the determination of total DJ-1 steady-state expression levels (top panels) or ASK1 immunoprecipitations performed. Western blots were probed for co-immunoprecipitated DJ-1 (middle panels) and ASK1 to demonstrate even immunoprecipitation efficiency (bottom panels). D, to determine their dimerization potential, HA-tagged wt, C106DD, and C106EE mutant DJ-1 were transiently co-transfected with Myc-tagged DJ-1 variants. The more stable [C106DD]DJ-1 but not the less stable [C106EE]DJ-1 (upper two input panels) Myc-co-immunoprecipitated with HA-tagged DJ-1 (Myc-immunoprecipitates Western probed with anti-Myc and co-immunoprecipitates probed with anti-HA and the lower two panels, respectively). E, to determine the incorporation of DJ-1 into the native ASK1 complexes, HEK293E cells were transiently co-transfected with ASK1/HA and the indicated N-terminal Myc tagged DJ-1 cysteine mutant constructs or pCMV vector control. After 36-h culturing, the cells were treated for 30 min without or with 1 mm H2O2, as indicated. Cell lysates were subjected to Sephacryl S-500 gel filtration. Fractions were collected and resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western probing with anti-ASK1 to detect ASK1/HA and 9E10 anti-Myc to detect Myc/DJ-1, as indicated. Shown are the fractions 42–56 containing ASK1 complexes well above 1000 kDa, and the peak fractions containing the expected Myc/DJ-1 dimer. Molecular mass standards are indicated to the rightof all Western blots. The results shown are representative for two or three independent experiments.

FIGURE 4.

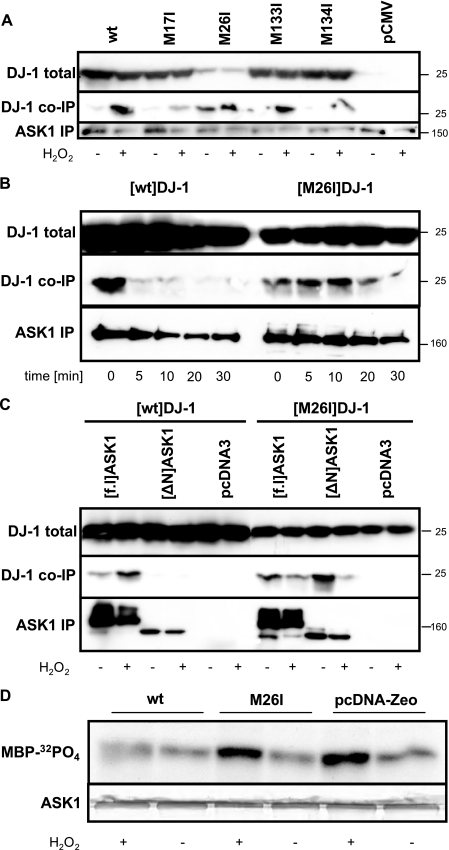

Influence of DJ-1 methionine mutations on ASK1 binding and kinase activity. HEK293E cells were co-transfected with full-length ASK1/HA (A and B) or as indicated the [ΔN]ASK1/HA mutant and pcDNA3 vector control (C) together with the indicated N-terminal Myc-tagged methionine mutant constructs. After 36-h culturing, the cells were treated for 30 min without (–) or with (+) 1 mm H2O2 and lysed directly (A and C), or treated for 30 min with 1 mm H2O2 followed by replacement with fresh medium for the indicated times (B). Whole cell lysates were directly Western probed with anti-Myc (top panels) to assess the relative steady-state expression levels of the DJ-1 mutants. Anti-HA-agarose immunoprecipitates were Western blotted and sequentially probed with anti-DJ-1 (middle panels) and anti-ASK1 (bottom panels). D, DJ-1–/– MEF cells stably transfected with untagged [wt]DJ-1 and [M26I]DJ-1 or pcDNA-Zeo vector control were treated for 30min with 500 μm H2O2 (+) or left untreated (–). Endogenous ASK1 was immunoprecipitated for immune complex kinase assays. Equal amounts of ASK1 in the reaction mixes are demonstrated by Coomassie Blue staining (lower panel). ASK1 phosphotransferase activity is measured by autoradiography of 32PO4 incorporation into the substrate myelin basic protein (upper panel). The results shown are representative for two or three independent experiments.

The constitutive ASK1 binding of peripheral cysteine mutants depended on the central Cys-106, as the double mutant Myc/[C53A/C106A]DJ-1 failed to co-immunoprecipitate with ASK1/HA (Fig. 2A). In fact, removing the oxidizable cysteine side chain at position 106 alone prevented binding of Myc/DJ-1 to ASK1/HA after H2O2 exposure (Fig. 2A). The triple cysteine-to-alanine DJ-1 mutant lacking all three cysteine residues also failed to co-immunoprecipitate with ASK1 (Fig. 2A). Thus, oxidation at Cys-106 is the critical step mediating binding of DJ-1 to ASK1 and appears to be influenced by the peripheral cysteine residues.

To test if oxidative modifications at the central redox residue Cys-106 were sufficient to mediate ASK1 binding, we attempted to simulate the negative charge introduced by Cys-106 oxidation by site-directed mutagenesis to aspartate and glutamate. However, in contrast to Myc/[wt]DJ-1 oxidized in HEK293E cells by H2O2 treatment, neither Myc/[C106D]DJ-1 nor Myc/[C106E]-DJ-1 co-immunoprecipitated with ASK1/HA (Fig. 2C). Thus, simple introduction of a negative charge at amino acid position 106 does not mediate DJ-1 binding to ASK1. In fact, Myc/[C106D]DJ-1 and Myc/[C106E]DJ-1 cannot be oxidized at position 106, hence their complete lack of ASK1 binding. These results are in accord with studies in Drosophila, where an equivalent mutation C104D did not mimic the activated state of DJ-1b, but rather showed the same loss of protective function as a C104A mutant (26).

It has been shown that the oxidation state of DJ-1 Cys-106 regulates its activity by incorporating an increasing number of oxygen atoms (15, 23). Thus, we have generated a series of artificial DJ-1 mutants inserting two and three aspartate and glutamate residues at position 106. Excitingly, Myc/[C106DD]DJ-1 was expressed at wt levels, and bound to ASK1 even without H2O2 treatment (Fig. 2C). Thus, simulation of higher oxidation states in the [C106DD]DJ-1 mutant appears to reflect the active state more closely than the single acidic side chain mutants at the molecular level, leading to enhanced co-immunoprecipitation with ASK1/HA.

Beyond C106DD, insertion of bulkier and even more negatively charged residues generally reduced DJ-1 protein expression. In perfect agreement with the notion that dimer formation correlates with DJ-1 protein stability, anti-Myc DJ-1 co-immunoprecipitated with HA-tagged wild-type DJ-1 and the more stable C106DD mutant (“homodimers”). In contrast, the less stable C106EE mutant failed to form homodimers. Significantly, HA/[C106DD] co-immunoprecipitated with Myc/[wt]DJ-1, whereas HA/[C106EE] failed to form “heterodimers” with Myc/[wt]DJ-1 (Fig. 2D). Nevertheless, despite generally reduced stability, Myc/[C106EE]DJ-1 as well as Myc/[C106DDD]DJ-1 and Myc/[C106EEE]DJ-1 strongly bound to ASK1 even in the absence of H2O2 (Fig. 2C). Thus, higher oxidation states at the Cys-106 might mediate ASK1 binding of DJ-1.

To confirm an oxidation-dependent incorporation of DJ-1 into the native ASK1 complex, we performed size exclusion chromatography. HEK293E cells were transiently co-transfected with ASK1/HA and Myc/DJ-1 constructs. After H2O2 treatments, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Sephacryl S-500 gel filtration. Compared with unstressed cells, H2O2 treatment led to the appearance of an earlier eluting, higher molecular mass peak, consistent with the formation of an ASK1 signalosome (34). In the absence of H2O2, Myc/[wt]DJ-1 eluted very late in the molecular mass range consistent with the expected dimer and was absent from the ASK1-containing fractions. After H2O2 exposure however, a considerable fraction of Myc/[wt]DJ-1 co-eluted earlier together with ASK1 (Fig. 2E), suggesting an incorporation of oxidized DJ-1 into the ASK1 signalosome. Consistent with the co-immunoprecipitation results (see above), considerable amounts of Myc/[C53A]DJ-1 and [C106DD]DJ-1 co-eluted with ASK-1 even in the absence of H2O2 (Fig. 2E), confirming that the constitutively ASK1 binding DJ-1 mutants were incorporated into native ASK1 complexes.

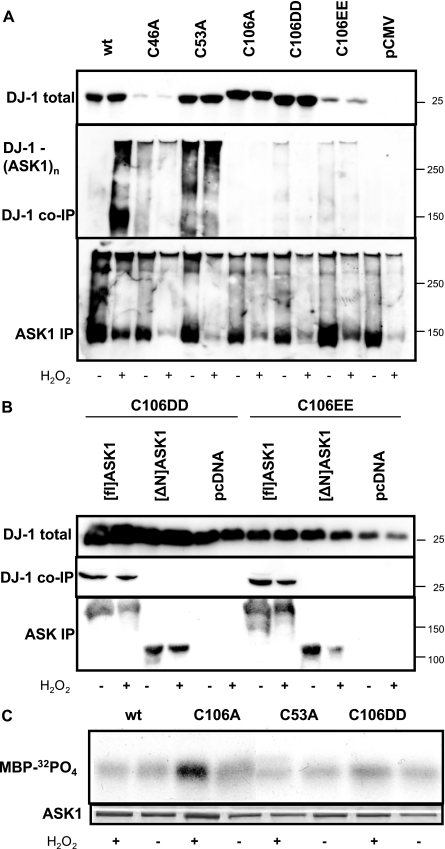

Formation of DJ-1-ASK1-mixed Disulfides—The dependence of DJ-1 binding to ASK1 on the central redox residue prompted us to consider mixed disulfide formation between ASK1 and DJ-1, because it was recently shown for thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) (35). HEK293E cells were transiently co-transfected with ASK1/HA and Myc/DJ-1 variants as above, but in this experiment ASK1 complexes immunoprecipitated with anti-HA were resolved by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Again Myc/[wt]DJ-1 co-immunoprecipitated with ASK1/HA only after H2O2 treatment. Under these conditions, some of the DJ-1-immunoreactive material recovered from ASK1 immunoprecipitates was incorporated into high molecular mass complexes (Fig. 3A). DJ-1-ASK1 adducts and higher molecular mass complexes (DJ-1-ASK1n) were observed, which could correspond to ASK1 oligomers (34) with incorporated DJ-1. Because such high molecular mass complexes of DJ-1 were dissolved upon reducing SDS-PAGE, these results indicate that DJ-1 is incorporated into the ASK1 signalosome via mixed disulfide bond formation. This process depended on the central Cys-106, because absolutely no [C106A]DJ-1 was recruited into the ASK1 complexes regardless whether the cells were treated with H2O2 or not (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

H2O2-induced formation of ASK1-DJ-1-mixed disulfides. A and B, HEK293E cells were co-transfected with full-length ASK1/HA (A) or as indicated the [ΔN]ASK1/HA mutant (B) together with vector controls. After 36-h culturing, the cells were treated for 30 min without (–) or with (+) 1 mm H2O2. Then cells were lysed and direct Western blots prepared for the determination of total DJ-1 steady-state expression levels (top panels) or ASK1 immunoprecipitations performed. ASK1 immunocomplexes were resolved by non-reducing (A) and reducing (B) SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed for co-immunoprecipitated DJ-1 (middle panels) and ASK1 to demonstrate even immunoprecipitation efficiency (bottom panels). C, DJ-1–/– MEF cells stably transfected with the indicated, untagged DJ-1 constructs were treated for 30 min with 500μm H2O2 (+) or left untreated (–). Endogenous ASK1 was immunoprecipitated for immune complex kinase assays. Equal amounts of ASK1 in the reaction mixes are demonstrated by Coomassie Blue staining (lower panel). ASK1 phosphotransferase activity is measured by autoradiography of 32PO4 incorporation into the substrate myelin basic protein (upper panel). The results shown are representative for two or three independent experiments.

Removal of the peripheral cysteine residues facilitated the formation of mixed disulfide ASK1 complexes, because robust amounts of [C53A]DJ-1 and even the less stable [C46A]DJ-1 were incorporated into ASK1 complexes, as revealed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). In contrast to Myc/[C53A]DJ-1, the C106DD and C106EE mutants appear to be bound the ASK1 complexes in a non-covalent manner, as seen by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2C) and size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2E), however the mixed disulfide high molecular weight smears were greatly reduced in these mutants (Fig. 3A). Thus, the presence of an oxidizable cysteine at position 106 is essential for the proper formation of DJ-1/ASK1-mixed disulfides. Myc/[C106DD]DJ-1 and Myc/[C106EE]DJ-1 did bind tightly to ASK1 at the N terminus (Fig. 3B), where also the negative regulator Trx1 is known to bind (30), and thus partly suppressed H2O2-mediated ASK1 kinase activation (Fig. 3C). However, these modifications only partially mimic some aspects of DJ-1 activation, which requires an oxidizable cysteine residue at the central position 106 for mixed disulfide formation.

Mutagenesis of the peripheral Cys-53 led to strong suppression ASK1 kinase activity (Fig. 3C) after H2O2 treatment. Moreover, mutation of Glu-18, which directly stabilizes Cys-106 sulfinic acid, was very recently shown to enhance activation of DJ-1 to protect against mitochondrial toxins (36). Thus, the oxidizability of the central Cys-106 is essential for the activation of the cytoprotective protein DJ-1.

PD-associated [M26I]DJ-1 Constitutively Binds to an Aberrant Site of ASK1—In contrast to the cysteine residues, the H2O2-dependent ASK1 co-immunoprecipitation properties of the methionine mutants were like wt with the exception of the PD-associated M26I mutant DJ-1 (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, [M26I]DJ-1 strongly bound to ASK1 even in completely unstressed cells. Similar to the poorly expressed peripheral mutant [C46A]DJ-1 (Fig. 2B), [M26I]DJ-1 showed a slower dissociation from ASK1/HA after H2O2 washout (Fig. 4B). However, in contrast to [wt]DJ-1, which failed to bind to co-transfected [ΔN]ASK1 (Fig. 4C), which lacks the N-terminal Trx1 binding site (30), [M26I]DJ-1 bound even stronger to [ΔN]ASK1 (Fig. 4C). Thus, the PD-associated [M26I]DJ-1 binds constitutively to ASK1 but apparently at a dysfunctional site.

To precisely measure the effects on ASK1 activity, we stably back-transfected [wt]DJ-1 and [M26I]DJ-1 in the null background of DJ-1–/– MEFs. Constructs without epitope tags were used to avoid any possible tagging artifacts (see above). In these stable DJ-1 back-transfectant MEF cell lines, ASK1 was stimulated with 30-min exposure to 500 μm H2O2. ASK1 activity was determined by immune complex kinase assays measuring radiolabeled phosphate incorporation into the substrate myelin basic protein. ASK1 activity was strongly induced by H2O2 in control DJ-1–/– MEF cells, and stable [wt]DJ-1 back-transfection completely suppressed ASK1 activation under these conditions. In contrast, [M26I]DJ-1 failed to suppress ASK1 activity in H2O2-treated MEF back-transfectants (Fig. 4D).

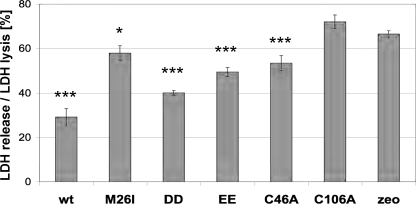

Mutations C106A and M26I Reduce Cytoprotection of DJ-1 against Oxidative Stress—To determine the influence on cytoprotective activity by DJ-1 mutations affecting ASK1 binding, we performed LDH release assays in DJ-1–/– MEFs (6). Both transient (see supplemental Fig. S3; transfection efficiency was 26 ± 2% determined in two independent transfections; 50 cells on each of the 8 parallel coverslips were counted) and stable retransfection of [wt]DJ-1 conferred significant cytoprotection after H2O2 treatment when compared with vector controls (supplemental Fig. S4 and Fig. 5). In contrast, the C106A mutants completely lost cytoprotective activity (supplemental Fig. S4 and Fig. 5), to the same extent as the known loss-of-function mutant [L166P]DJ-1 (results not shown). This is consistent with [C106A]DJ-1 failure to bind to ASK1 (Figs. 2A and 3A and Ref. 6) and suppress ASK1 kinase activation (Fig. 3C) after oxidative stress.

FIGURE 5.

C106A and M26I mutations reduce DJ-1 cytoprotective activity. DJ-1–/– MEFs were stably transfected with the indicated DJ-1 constructs or vector control. Cells were exposed for 16 h to 20 μm H2O2, and cytotoxicity was measured by LDH release. Error bars delineate standard deviation of triplicate samples; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. These results are representative of two independent experiments.

The peripheral cysteine mutants [C46A]DJ-1 and [C53A]DJ-1 retained the cytoprotective activity (supplemental Fig. S4 and Fig. 5). The constitutively ASK1 binding mutants had different effects on cytoprotection. [C106DD]DJ-1 and [C106EE]DJ-1 showed partial cytoprotective activity (Fig. 5), although the final incorporation into the mixed disulfide ASK1 complex might be missing for complete cytoprotective activity. In contrast, the PD-associated [M26I]DJ-1 showed significantly reduced cytoprotection in H2O2-treated MEF cells (supplemental Fig. S4 and Fig. 5). Therefore, Cys-106 is the essential residue conferring the activation of DJ-1 upon oxidative stress facilitated by the peripheral cysteine residues, and the PD-associated M26I mutation interferes with this cytoprotective process.

[M26I]DJ-1 Fails to Suppress Nuclear Export of Daxx—One of the downstream effects of ASK1 activation is a nucleus to cytosol export of the death-associated protein Daxx (37, 38). To determine the effects of DJ-1 on Daxx translocation, DJ-1–/– MEF cells stably re-transfected with vector, [wt]DJ-1 and [M26I]DJ-1 were transiently transfected with FLAG/Daxx. In the absence of oxidative stress, FLAG/Daxx localized to distinct nuclear subcompartments. Treatment for 30 min with 500 μm H2O2 caused significant translocation of Daxx from the nucleus into the cytosol, as evidenced by anti-FLAG immunofluorescence (Fig. 6). [wt]DJ-1 abolished nuclear export of FLAG/Daxx under these conditions (Fig. 6), consistent with previous reports in cell culture and mouse models (24, 39). In contrast, the PD-associated mutant [M26I]DJ-1 lost nuclear retention of FLAG/Daxx, leading to highly significant nuclear export of Daxx into the cytosol, where it is known to promote cell death (40). In conclusion, homozygous M26I mutation impairs the ASK1 kinase- and Daxx translocation-suppressive activities of DJ-1, and loss of these functions is likely to contribute to the PD pathogenic effects of [M26I]DJ-1.

FIGURE 6.

Loss of suppression of Daxx translocation by the M26I DJ-1 mutation. DJ-1–/– MEF cells stably transfected with untagged [wt]DJ-1 and [M26I]DJ-1 or pcDNA-Zeo vector control were treated for 30 min with 500 μm H2O2 (+) or left untreated (–) after transient transfection with FLAG/Daxx. Nuclear export of FLAG/Daxx was scored by counting the percentage of cells with cytosolic anti-FLAG immunostaining. In the absence of H2O2 (panels 1–3), FLAG/Daxx shows distinct subnuclear localization and little cytosolic staining outside the nucleus (counterstained with Hoechst 33342). After H2O2 challenge, vector controls show significant increase in cytosolic FLAG/Daxx staining (panel 6), which was suppressed in DJ-1–/– MEFs stably re-transfected with [wt]DJ-1 (panel 4). In contrast, stable re-transfection with [M26I]DJ-1 failed to suppress nuclear export of FLAG/Daxx (panel 5). The graph shows mean values from three independent experiments ± S.E.; **, p < 0.02.

DISCUSSION

Although DJ-1 mutations account for only very few PD cases (41), DJ-1 is involved in several processes that are thought to underlie PD pathogenesis (42). In this context, one of the most relevant functions of DJ-1 is to promote cytoprotection under oxidative stress. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms of oxidative activation of DJ-1 and to identify critical residues that account for this function, we have mutagenized all oxidizable residues. We identified Cys-106 as the functionally critical amino acid that promotes direct binding of DJ-1 to ASK1 and cytoprotection in oxidatively stressed cells. We found that after H2O2 treatment DJ-1 is incorporated into ASK1 complexes and forms mixed disulfide bonds involving the central Cys-106 with the N terminus of ASK1, similar to a known negative regulator, Trx1. The two peripheral cysteine residues Cys-46 and Cys-53 appeared to modulate DJ-1 activation. Finally, [M26I]DJ-1 was found to have reduced expression levels, aberrantly bound ASK1, and lost cytoprotective activity.

The effects of PD-associated mutations on DJ-1 protein stability are dramatic for L166P (2–5, 7, 10), but much less obvious for other point mutations, such as M26I (8). Previous reports on steady-state levels of [M26I]DJ-1 were controversial. Proteasomal destabilization of FLAG/[M26I]DJ-1 was observed in stably transfected mouse NIH3T3 cells (43) and of [M26I]DJ-1/V5/HIS in transiently transfected Met-17 neuroblastoma cells and untagged [M26I]DJ-1 in rat PC12 cells (11), but not of [M26I]DJ-1/FLAG in transiently transfected Chinese hamster ovary and HEK293 cells (7, 44) and [M26I]DJ-1/Myc/HIS in transiently transfected human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (4). However, all these cellular studies agreed that [M26I]DJ-1 retained dimerization capacity (4, 7, 11, 43, 44), in contrast to a very recent report describing reduced stability and impaired homodimerization of purified recombinant [M26I]DJ-1/HIS (45). Xu et al. (46) noted some slightly enhanced degradation of [M26I]DJ-1/Myc/HIS in stably transfected SH-SY5Y cells, and found reduced cytoprotective activity in these neuroblastoma cells, whereas Liu et al. (47) reported loss of neuroprotective activity of lenti-[M26I]DJ-1 in primary midbrain dopaminergic neurons despite almost wt expression levels of the lentivirally transduced [M26I]DJ-1 protein. Here we show that in transiently transfected cells [M26I]DJ-1 expression is reduced due to protein destabilization, especially in DJ-1 knockout MEFs that are devoid of potentially stabilizing [wt]DJ-1 homomers. In this unique experimental model of homozygous M26I mutation, we found significantly reduced cytoprotective activity of Myc/[M26I]DJ-1.

Met-26 faces toward the interior of the protein and is part of the hydrophobic core. However, substitution of methionine with isoleucine is very conservative, and in fact leucine residues are present at this position in invertebrate and bacterial DJ-1 sequences (supplemental Fig. S1). Nevertheless, the M26I mutation causes local structure perturbations and packing defects in the hydrophobic core (48, 49), thereby destabilizing the DJ-1 protein and leading to loss of cytoprotective function. Thus, although the effects are not as dramatic as the L166P mutation, these studies collectively show that the M26I mutation also contributes to PD pathogenesis in the homozygous state of the affected patient (8) by depletion of DJ-1.

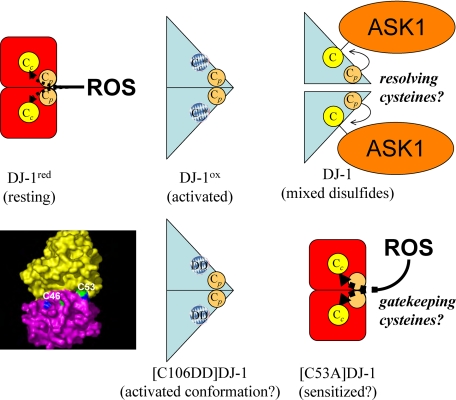

Among the three human cysteines, most previous studies identified Cys-106 as the most reactive and functionally important residue (15, 17, 26, 28, 50), except for one study, which identified Cys-53 to account for the redox-dependent chaperone activity and cytoprotection of DJ-1 (22). Here we show that [C53A]DJ-1 retained the capacity to bind to ASK1 in H2O2-treated HEK293E cells. In contrast, oxidation-dependent binding of DJ-1 to ASK1 was abolished by Cys-106 mutations. Like the oxidation-deficient [C106A]DJ-1, the engineered oxidation-mimicking mutants [C106D]DJ-1 and [C106E]DJ-1 did not bind to ASK1, neither in the presence nor in the absence of H2O2. Thus, single insertion of negatively charged amino acids at position 106 might not fully reflect the charge distribution of the higher oxidation state(s) that might be necessary for ASK1 binding. However, insertion of more oxygen atoms in the [C106DD]DJ-1 mutant is sufficient to mediate binding to ASK1 and at least partial cytoprotection. [C106EE]DJ-1 also had ASK1 binding and cytoprotective activity, albeit with lower efficacy most likely due to reduced protein stability because of the introduction of more bulky and charged residues in the sensible active site of DJ-1. Thus, higher order oxidation events at Cys-106 activate the cytoprotective protein DJ-1, and the C106DD mutation best mimics DJ-1 activation steps toward initial, non-covalent ASK1 binding. However, because [C106DD]DJ-1 lacks the reactive central cysteine, it does not further form mixed disulfide bonds within the ASK1 signalosome. We hypothesize that the central C106DD mutation “opens” the DJ-1 conformation to reveal ASK1 binding site(s) (Fig. 7) and thereby resulting in the observed ASK1 bindings and partial cytoprotection. The full cytoprotective activity of DJ-1 perhaps requires more complete, mixed disulfide-mediated incorporation into the ASK1 signalosome, for which the C106DD lacks the necessary cysteine. A very elegant alternative approach to modulate the oxidizability of the Cys-106 redox center was very recently reported. Rational site-directed mutagenesis of the Cys-106 sulfinic acid stabilizing E18 side chain altered the activation of DJ-1 by mitochondrial toxins (36). Collectively, these findings clearly demonstrate the critical importance of the dynamic central redox site for DJ-1 function as an cytoprotective protein against oxidative stress.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic drawing of proposed DJ-1 activation states. The surface contour plot of the DJ-1 dimer (lower left) shows the cysteine side chains of each homomer (green residues belong to the yellow homomer, blue residues to the purple homomer). The Cys-53 side chains are prominently localized at the edge of the dimer interface, Cys-46 partially buried within the dimer interface. The Cys-106 residues are deeply buried within the DJ-1 each homomer, necessitating a channel for ROS to enter the central active site Cys-106 (Cc). A peripheral (Cp) redox center that appears to comprise Cys-53 and perhaps other oxidizable and/or structural residues (Cys-46 and Met-26) could gate the accessibility of reactive oxygen species to Cys-106 and activate the central site (Cc*). Peripheral redox center mutants might be sensitized due to deregulated gating of reactive oxygen species, allowing unquenched access to the active center. Alternatively, Cp might function as “resolving cysteines,” reducing transiently formed mixed disulfide bonds of Cys-106 with effector proteins, such as ASK1. Formation of Cc* might “open” the DJ-1 conformation, allowing access of the buried Cys-106 to cysteines within with N terminus of ASK1 to form mixed disulfides. Such an open conformation may also be induced by the C106DD mutation, which causes tight but non-covalent binding of DJ-1 to ASK1. See text for further details.

Cys-106 mutations abolish anti-oxidative functions of DJ-1 without perturbing protein stability. In contrast, Cys-46 in the dimer interface has a structural role. Here we show that [C46A]DJ-1 and [tripleC]DJ-1 have reduced protein expression levels, consistent with a previous study reporting that [C46A]DJ-1 had impaired dimer formation (32), which is believed to be crucial for DJ-1 protein stability. Interestingly, we found here that the peripheral cysteine residues Cys-46 and Cys-53 modulated the Cys-106-dependent binding of DJ-1 to ASK1. Remarkably, the [C46A]DJ-1 mutant strongly bound to ASK1 despite relatively low protein expression levels. The stable [C53A]DJ-1 bound to ASK1 even in the absence of H2O2, and this effect was abrogated in the double mutant [C53A/C106A]DJ-1. The increased steady-state binding may be, at least in part, due to slower off-rates. Thus, the peripheral cysteine residues might reduce the oxidizability of Cys-106 by scavenging reactive oxygen species on their way to the redox center Cys-106 inside the DJ-1 molecule. Non-oxidizable peripheral cysteine mutants might de-quench DJ-1, thereby constitutively stimulating stronger DJ-1 binding to ASK1. In this model, peripheral cysteine residues form a secondary redox site that influences oxidative activation of DJ-1 at the central Cys-106 (gatekeeping cysteines (Fig. 7)). Alternatively, the peripheral cysteine residues might reduce the mixed disulfide bonds between the DJ-1 Cys-106 and ASK1 (resolving cysteines (Fig. 7)). Such a mechanism was proposed for Trx1 (35).

Interestingly, peripheral cysteine mutations of DJ-1 showed extreme loss of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal regulated kinase kinase kinase (MEKK1) suppression (see Fig. 6B of the recent paper by Mo et al. (51)). Perhaps such apparent dominant-negative effects of [C46A]DJ-1 and [C53A]DJ-1 on MEKK1 might arise from DJ-1 sequestration in the ASK1 complex. Therefore, DJ-1 might act as a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase signaling integrator. Surprisingly, the PD-associated [M26I]DJ-1 also showed constitutive ASK1 binding despite reduced protein levels. Nevertheless, such ASK1 binding of [M26I]DJ-1 was futile, because [M26I]DJ-1 did not suppress ASK1 kinase activity, Daxx translocation, and H2O2 cytotoxicity, in contrast to [C46A]DJ-1 and [C53A]DJ-1, which did mediate cytoprotection. We propose that these functional differences are due to altered ASK1 binding site(s). We have previously shown that in H2O2-treated cells [wt]DJ-1 binds to ASK1 after dissociation of Trx1 (6), suggesting a replacement from the same binding site. Our finding of constitutive binding of [M26I]DJ-1 to [ΔN]ASK1, which lacks the binding sites for both negative ASK1 regulator proteins Trx1 (30) and [wt]DJ-1 (Fig. 4D), is consistent with the hypothesis that the PD-mutant [M26I]DJ-1 strongly binds in a dysfunctional manner to a different site than the cytoprotective [wt]DJ-1.

In conclusion, Cys-106 is the central oxidizable residue that mediates recruitment and mixed disulfide formation of DJ-1 with ASK-1 complexes. This could contribute to the cytoprotective activity of DJ-1, although additional mechanisms of this multifunctional protein may confer full protection against oxidative stresses. The peripheral cysteines Cys-46 and Cys-53 as well as the PD-associated mutant M26I contribute to stable DJ-1 homodimer formation and modulate oxidant-induced activation of DJ-1. Impaired oxidation-dependent activation of the cytoprotective redox sensor DJ-1 may account for the pathogenesis of M26I mutation bearers and contribute to PD in general.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eve Holtorf for technical assistance, Stephen Hall (Alphagenix) for the donation of anti-DJ-1, an anonymous referee for helpful suggestions, Hubert Kettenberger for molecular modeling advice, and Christian Haass, Wolfgang Wurst, and Thomas Gasser for support.

This work was supported by the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN-2 Grant 01GS0466), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Program Project Grant SFB596 A12), a collaborative research contract with Novartis Pharma Ltd., and the Hertie Foundation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Table S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PD, Parkinson disease; ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Trx1, thioredoxin 1; wt, wild-type; HA, hemagglutinin; MEKK1, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal regulated kinase kinase kinase 1; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

References

- 1.Bonifati, V., Rizzu, P., van Baren, M. J., Schaap, O., Breedveld, G. J., Krieger, E., Dekker, M. C. J., Squitieri, F., Ibanez, P., Joosse, M., van Dongen, J. W., Vanacore, N., van Swieten, J. C., Brice, A., Meco, G., van Duijn, C. M., Oostra, B. A., and Heutink, P. (2003) Science 299 256–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macedo, M. G., Anar, B., Bronner, I. F., Cannella, M., Squitieri, F., Bonifati, V., Hoogeveen, A., Heutink, P., and Rizzu, P. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 2807–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller, D. W., Ahmad, R., Hague, S., Baptista, M. J., Canet-Avilés, R., McLendon, C., Carter, D. M., Zhu, P.-P., Stadler, J., Chandran, J., Klinefelter, G. R., Blackstone, C., and Cookson, M. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 36588–36595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore, D. J., Zhang, L., Dawson, T. M., and Dawson, V. L. (2003) J. Neurochem. 87 1558–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olzmann, J. A., Brown, K., Wilkinson, K. D., Rees, H. D., Huai, Q., Ke, H., Levey, A. I., Li, L., and Chin, L.-S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 8506–8515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Görner, K., Holtorf, E., Waak, J., Pham, T.-T., Vogt-Weisenhorn, D. M., Wurst, W., Haass, C., and Kahle, P. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 13680–13691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baulac, S., LaVoie, M. J., Strahle, J., Schlossmacher, M. G., and Xia, W. (2004) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 27 236–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abou-Sleiman, P. M., Healy, D. G., Quinn, N., Lees, A. J., and Wood, N. W. (2003) Ann. Neurol. 54 283–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hering, R., Strauss, K. M., Tao, X., Bauer, A., Woitalla, D., Mietz, E.-M., Petrovic, S., Bauer, P., Schaible, W., Müller, T., Schöls, L., Klein, C., Berg, D., Meyer, P. T., Schulz, J. B., Wollnik, B., Tong, L., Krüger, R., and Riess, O. (2004) Hum. Mutat. 24 321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Görner, K., Holtorf, E., Odoy, S., Nuscher, B., Yamamoto, A., Regula, J. T., Beyer, K., Haass, C., and Kahle, P. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 6943–6951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackinton, J., Ahmad, R., Miller, D. W., van der Brug, M. P., Canet-Avilés, R. M., Hague, S. M., Kaleem, M., and Cookson, M. R. (2005) Mol. Brain Res. 134 76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandopadhyay, R., Kingsbury, A. E., Cookson, M. R., Reid, A. R., Evans, I. M., Hope, A. D., Pittman, A. M., Lashley, T., Canet-Avilés, R., Miller, D. W., McLendon, C., Strand, C., Leonard, A. J., Abou-Sleiman, P. M., Healy, D. G., Ariga, H., Wood, N. W., de Silva, R., Revesz, T., Hardy, J. A., and Lees, A. J. (2004) Brain 127 420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi, J., Sullards, M. C., Olzmann, J. A., Rees, H. D., Weintraub, S. T., Bostwick, D. E., Gearing, M., Levey, A. I., Chin, L.-S., and Li, L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 10816–10824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann, M., Müller, V., Görner, K., Kretzschmar, H. A., Haass, C., and Kahle, P. J. (2004) Acta Neuropathol. 107 489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canet-Avilés, R. M., Wilson, M. A., Miller, D. W., Ahmad, R., McLendon, C., Bandyopadhyay, S., Baptista, M. J., Ringe, D., Petsko, G. A., and Cookson, M. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 9103–9108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinat, C., Shendelman, S., Jonason, A., Leete, T., Beal, M. F., Yang, L., Floss, T., and Abeliovich, A. (2004) PLoS Biol. 2 e327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taira, T., Saito, Y., Niki, T., Iguchi-Ariga, S. M. M., Takahashi, K., and Ariga, H. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5 213–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bretaud-Marsollier, S., Allen, C., Ingham, P. W., and Bandmann, O. (2007) J. Neurochem. 100 1626–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, R. H., Smith, P. D., Aleyasin, H., Hayley, S., Mount, M. P., Pownall, S., Wakeham, A., You-Ten, A. J., Kalia, S. K., Horne, P., Westaway, D., Lozano, A. M., Anisman, H., Park, D. S., and Mak, T. W. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 5215–5220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meulener, M., Whitworth, A. J., Armstrong-Gold, C. E., Rizzu, P., Heutink, P., Wes, P. D., Pallanck, L. J., and Bonini, N. M. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15 1572–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ved, R., Saha, S., Westlund, B., Perier, C., Burnam, L., Sluder, A., Hoener, M., Rodrigues, C. M. P., Alfonso, A., Steer, C., Liu, L., Przedborski, S., and Wolozin, B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 42655–42668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shendelman, S., Jonason, A., Martinat, C., Leete, T., and Abeliovich, A. (2004) PLoS Biol. 2 e362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou, W., Zhu, M., Wilson, M. A., Petsko, G. A., and Fink, A. L. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 356 1036–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junn, E., Taniguchi, H., Jeong, B. S., Zhao, X., Ichijo, H., and Mouradian, M. M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 9691–9696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, Y., Gehrke, S., Haque, M. E., Imai, Y., Kosek, J., Yang, L., Beal, M. F., Nishimura, I., Wakamatsu, K., Ito, S., Takahashi, R., and Lu, B. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 13670–13675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meulener, M. C., Xu, K., Thomson, L., Ischiropoulos, H., and Bonini, N. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 12517–12522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinumi, T., Kimata, J., Taira, T., Ariga, H., and Niki, E. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 317 722–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson, M. A., Collins, J. L., Hod, Y., Ringe, D., and Petsko, G. A. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 9256–9261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao, X., and Tong, L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 31372–31379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saitoh, M., Nishitoh, H., Fujii, M., Takeda, K., Tobiume, K., Sawada, Y., Kawabata, M., Miyazono, K., and Ichijo, H. (1998) EMBO J. 17 2596–2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honbou, K., Suzuki, N. N., Horiuchi, M., Niki, T., Taira, T., Ariga, H., and Inagaki, F. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 31380–31384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito, G., Ariga, H., Nakagawa, Y., and Iwatsubo, T. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 339 667–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdallah, J., Caldas, T., Kthiri, F., Kern, R., and Richarme, G. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189 9140–9144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noguchi, T., Takeda, K., Matsuzawa, A., Saegusa, K., Nakano, H., Gohda, J., Inoue, J., and Ichijo, H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 37033–37040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nadeau, P. J., Charette, S. J., Toledano, M. B., and Landry, J. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 3903–3913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blackinton, J., Lakshminarasimhan, M., Thomas, K. J., Ahmad, R., Greggio, E., Raza, A. S., Cookson, M. R., and Wilson, M. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284 6476–6485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ko, Y.-G., Kang, Y.-S., Park, H., Seol, W., Kim, J., Kim, T., Park, H.-S., Choi, E.-J., and Kim, S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 39103–39106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song, J. J., and Lee, Y. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 47245–47252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karunakaran, S., Diwakar, L., Saeed, U., Agarwal, V., Ramakrishnan, S., Iyengar, S., and Ravindranath, V. (2007) FASEB J. 21 2226–2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salomoni, P., and Khelifi, A. F. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abou-Sleiman, P. M., Healy, D. G., and Wood, N. W. (2004) Cell Tissue Res. 318 185–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abeliovich, A., and Beal, M. F. (2006) J. Neurochem. 99 1062–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi-Niki, K., Niki, T., Taira, T., Iguchi-Ariga, S. M. M., and Ariga, H. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320 389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herrera, F. E., Zucchelli, S., Jezierska, A., Lavina, Z. S., Gustincich, S., and Carloni, P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 24905–24914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hulleman, J. D., Mirzaei, H., Guigard, E., Taylor, K. L., Ray, S. S., Kay, C. M., Regnier, F. E., and Rochet, J.-C. (2007) Biochemistry 46 5776–5789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, J., Zhong, N., Wang, H., Elias, J. E., Kim, C. Y., Woldman, I., Pifl, C., Gygi, S. P., Geula, C., and Yankner, B. A. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 1231–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu, F., Nguyen, J. L., Hulleman, J. D., Li, L., and Rochet, J.-C. (2008) J. Neurochem.

- 48.Lakshminarasimhan, M., Maldonado, M. T., Zhou, W., Fink, A. L., and Wilson, M. A. (2008) Biochemistry 47 1381–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malgieri, G., and Eliezer, D. (2008) Protein Sci. 17 855–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Witt, A. C., Lakshminarasimhan, M., Remington, B. C., Hasim, S., Pozharski, E., and Wilson, M. A. (2008) Biochemistry 47 7430–7440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mo, J.-S., Kim, M.-Y., Ann, E.-J., Hong, J.-A., and Park, H.-S. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15 1030–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.