Abstract

Cellular FLIP (Flice-like inhibitory protein) is critical for the protection against death receptor-mediated cell apoptosis. In macrophages, FLIP long (FLIPL) and FLIP short (FLIPS) mRNA was induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, mediated through NF-κB. However, we observed TNFα reduced the protein level of FLIPL, but not FLIPS, at 1 and 2 h. Similar results were observed with lipopolysaccharide. The reduction of FLIPL by TNFα was not mediated by caspase 8, or through JNK or Itch, but was suppressed by inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway employing chemical inhibitors, a dominant negative Akt-1, or Akt-1 small interfering RNA. The reduction of FLIPL resulted in the short term induction of caspase 8-like activity, which augmented NF-κB activation. A co-immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated that Akt-1 physically interacts with FLIPL. Moreover, TNFα enhanced FLIPL serine phosphorylation, which was increased by activated Akt-1. Serine 273, a putative Akt-1 phosphorylation site in FLIPL, was critical for the activation-induced reduction of FLIPL. Thus, these observations document a novel mechanism where by TNFα facilitates the reduction of FLIPL protein, which is dependent on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling.

Cellular FLIP (Flice-like inhibitory protein) negatively modulates the caspase 8-dependent apoptotic cascade triggered by the activation of death receptors, such as the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)2 receptor-1 and Fas (1–3). Although the flip gene is expressed as multiple splice variants in many tissues (1, 4), it produces two major isoforms at the protein level, FLIP long (FLIPL) and FLIP short (FLIPS). Both isoforms contain two death effector domains in the N terminus that allow for interaction with the adapter molecule Fas-associated death domain. FLIPL, the more abundantly expressed isoform in most cell types, additionally contains an nonfunctional caspase activation-like domain in its C terminus (1). The increased expression of FLIP renders tumor cells and macrophages from the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis resistant to death receptor and chemotherapeutic drug-mediated apoptosis (5–8), whereas the level of FLIP correlates with tumor progression and patient outcomes (9).

To date, the transcriptional and post-transcription regulation of FLIP has not been fully elucidated. NF-κB strongly up-regulates the expression of FLIPL and FLIPS (10), and TNFα and LPS, which activate NF-κB, are known to induce FLIP (11, 12). Additionally, Akt has been implicated in the induction of FLIP (13–16). Post-transcriptionally, FLIPL and FLIPS are regulated by ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (17–20). As reported recently (21), the TNFα-accelerated FLIPL turnover in mouse hepatocytes and mouse embryonic fibroblasts was mediated through JNK activation that occurs when NF-κB activation is suppressed. The JNK-mediated phosphorylation of E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch results in the ubiquitination and degradation of FLIPL. However, the role of TNFα in the post-transcriptional regulation of FLIP in the absence of NF-κB inhibition or the prolonged activation of JNK is not known.

The dysregulation of macrophage function contributes to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, atherosclerosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (22–26). Our prior observations demonstrate that FLIP is critical for the protection of macrophages against death receptor-mediated apoptosis in rheumatoid arthritis (8, 27); however, knowledge of the mechanisms that regulate FLIP in macrophages is incomplete. While characterizing the expression of FLIP in macrophages, in contrast to expectations, we noticed that activation with TNFα or LPS actually reduced the protein levels of FLIPL, but not FLIPS, at 1 and 2 h, even though the mRNA of both isoforms was increased. The activation-induced reduction of FLIPL resulted in the increased activation of caspase 8, which promoted the activation of NF-κB and the expression of FLIP mRNA. Our observations also demonstrate that the PI3K/Akt-1 (Akt) pathway mediates the activation-induced reduction of FLIPL by the phosphorylation of FLIPL at serine 273. These observations identify a novel pathway regulating the decision for life and death of the macrophage following activation, and they identify the regulation of FLIPL as a potential therapeutic target.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture—Human macrophages were differentiated from monocytes isolated from the buffy coats (Lifesource, Glenview, IL) from healthy donors. Mononuclear cells were obtained by histopaque gradient centrifugation and monocytes by counter-current centrifugal elutriation (JE-6B; Beckman Coulter, Palo Alto, CA) in the presence of 10 μg/ml polymyxin B sulfate (Sigma), as previously describe RPMI medium without serum and were differentiated in vitro for 7 days in RPMI containing 20% heat-inactivated FBS, 1 μg/ml polymyxin B sulfate, 0.35 mg/ml l-glutamine, 120 units/ml penicillin and streptomycin (20% FBS/RPMI) (27–31). RAW264.7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS.

Adenovirus Infection of Primary Macrophages—A control adenoviral empty vector (CMV-blank) and adenoviral vectors expressing a FLIPL, a super-repressor IκBα, a constitutively activated myristilated AKT mutant (Myr-AKT), and a dominant negative form of AKT (DN-AKT) were employed. Macrophages were infected with adenoviral vectors in RPMI medium without serum for 2 h. After infection, 20% FBS/RPMI was added, and the cells were incubated overnight. The macrophages were then washed twice with PBS and incubated in 20% FBS/RPMI for an additional 24 h and then employed as described under “Results.”

Caspase 8-like Activity—Macrophages were treated as indicated and harvested. Cell lysates were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioVision Research Products, Palo Alto, CA). Cell lysates containing 180 μg of protein were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with the caspase 8 (Ac-IETD-AFC) synthetic fluorogenic substrate. The samples were read on a fluorometer at 400-nm excitation and 505-nm emission.

Apoptosis—Macrophages were harvested, fixed in 70% ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml). The apoptotic profile was determined by flow cytometry utilizing a Beckman-Coulter EpicsXL flow cytometer and system 2 software, as described (27, 31, 32). The hypodiploid DNA peak (<2 n DNA) immediately adjacent to the G0/G1 peak (2 n DNA) represented apoptotic cells and was quantified by histogram analyses. Objects with minimal light scatter representing debris were excluded.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR—Total RNA was isolated from macrophages using the TRIzol (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription with oligo(dT) primer was performed employing the reverse transcription system kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real time PCR was carried out employing TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems). The sequences for the FLIP forward and reverse primers were as follows: forward primer for both FLIPL and FLIPS 5′-CAAGCAGTCTGTTCAAGGA, reverse primer of FLIPL 5′-GCCAAGCTGTTCCTTAAGA, reverse primer of FLIPS 5′-ATGGGCATAGGGTGTTATC. The probe, 5′-TGTTCTCCAAGCAGCAATCCA, was labeled with carboxyfluorescein-aminohexyl amidite. The control human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase primers and VIC-labeled probe were obtained from Applied Biosystems and employed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR was performed with a ABI PRISM™ 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) in a final volume of 20 μl containing 60 ng of complementary DNA, 800 nm each of the forward and reverse primers, and 250 nm of the probes. The amplification program was: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. Quantitative values were derived from the threshold cycle number (Ct) (11, 32). The experiments were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. A relative gene expression was determined by assigning the control a relative value of 1.0, with all other values relative to the control.

siRNA Transfection—The forced reduction of caspase 8, Akt-1, and Itch in macrophages was achieved employing the SMARTpools of caspase 8, Akt-1, or Itch siRNA, (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). A nonspecific siRNA was employed as the control. Macrophages in 6-well plates were transfected with siRNAs by Lipofectamine methods following vender's protocol, as previously described (32, 33). After 4 h, FBS was added to bring the culture medium to 20% FBS, and the cells were cultured for an additional 48 h.

Immunoblot Analysis—Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (27–31). Briefly, whole cell extracts were prepared from macrophages that were treated as indicated under “Results.” The proteins (60 μg) were electrophoresed on SDS-PAGE 12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon-P (Millipore) by semidry electroblotter (Bio-Rad). The membranes were then blocked in 5% nonfat milk PBS/0.2% Tween 20 (PBST) and subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-human FLIP (Alexis Biochem, Carlsbad, CA), anti-Akt, anti-phospho-Akt Ser473, anti-caspase 8 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-Itch, anti-phosphoserine (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), anti-IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-HA-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (Roche Applied Science), and anti-β-actin (Sigma). The membranes were washed in PBST and incubated with either donkey anti-rat, anti-rabbit, or anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:3300 dilution; Amersham Biosciences). The specific proteins were detected by Enhanced Chemiluminescent detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunoprecipitation and Co-immunoprecipitation Method— To characterize the FLIPL serine phosphorylation status, FLIPL was pulled down by immunoprecipitation and detected by anti-phosphoserine antibody. Briefly, whole cell extracts containing 600 μg of protein were precleared with 50 μl of protein G-agarose beads with rotation at 4 °C for 1 h. The precleared lysates were collected and incubated with FLIP antibody (5 μg) for 1 h, followed by the addition of 50 μl of protein G-agarose beads, which were incubated with rocking overnight at 4 °C. After being washed four times, the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblot analysis for the serine phosphorylation of FLIPL employing an anti-phosphoserine specific antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). To detect the interaction between FLIPL and Akt, 600 μg of precleared cell lysates from macrophages that were co-infected with adenoviral vectors expressing FLIPL and HA-Myr-Akt were incubated with anti-FLIP or anti-HA antibodies for 1 h and then further incubated overnight after adding 50 μl of protein G-agarose beads. The rat IgG and rabbit IgG were employed as negative controls for FLIP and HA antibodies. After washing, the samples were subjected to immunoblot analysis and probed with FLIP or anti-HA antibodies.

In Vivo [32P]Orthophosphate Cell Labeling for FLIP Phosphorylation—Macrophages in 6-well plates were infected with an adenoviral vector expressing Myr-Akt or the CMV control vector. After 24 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with [32P]orthophosphate (0.42 mCi/ml) in minimum Eagle's medium without phosphate for 2 h. FLIP was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLIP antibody and separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was then dried, and FLIPL phosphorylation status was detected by autoradiography.

Site-directed Mutagenesis of FLIPL and Development of Cell Lines—Serine residue 273 on FLIPL, a putative Akt phosphorylation site, was point mutated to alanine by a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the supplier's protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). In brief, we used retroviral pLXIN-FLIPL expression vector as template and used the following oligonucleotides to make point mutation serine 273 to alanine (mutated codon indicated as underlined): 5′-CGA GAC ACC TTC ACT GCC CTG GGC TAT GAA GTC-3′ (forward), 5′-GAC TTC ATA GCC CAG GGC AGT GAA GGT GTC TCG-3′ (reverse). The sequences of wild type and mutant form of FLIPL cDNA in pLXIN vectors were verified to be correct by DNA sequencing. The pLXIN-FLIPL wild type or mutant plasmids were transfected into packaging cell line PT67, and recombinant retroviral RNAs were packaged into infectious, replication-incompetent particles. Culture media containing the viral particles were collected and used to infect RAW264.7 cells. Stably expressing wild type and mutant FLIPL expressing cell lines were selected in medium containing 600 μg/ml geneticin (G418).

Statistical Analysis—The experimental data are presented as the means ± S.E. The statistical differences between groups were determined by t test. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

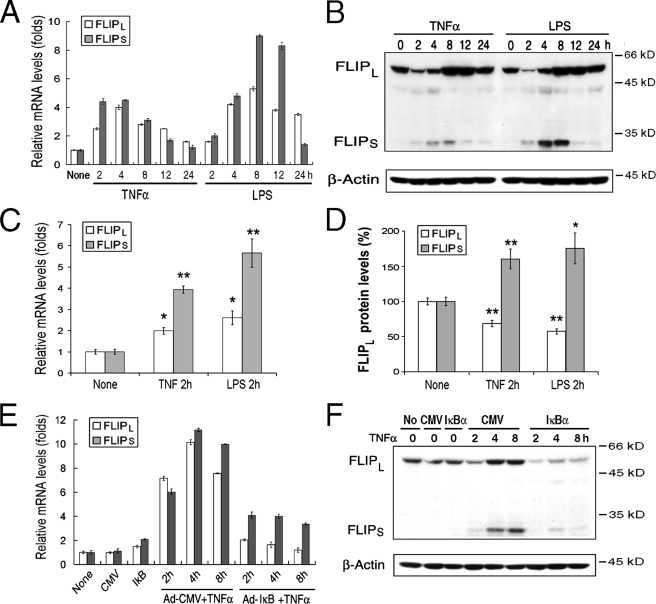

FLIPL Is Regulated Differently by TNFα at the mRNA and Protein Levels—Studies were performed to determine the effect of activation through the TNF receptor pathway on the expression of FLIP employing normal in vitro differentiated macrophages. Incubation of macrophages with TNFα resulted in the induction of mRNA for both FLIPL and FLIPS (Fig. 1A), which were significantly (p < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively) increased by 2 h (Fig. 1, A and C) and diminished between 12 and 24 h (Fig. 1A). The induction of FLIP at the protein level was very different. By immunoblot analysis TNFα-induced FLIPS was significantly increased (p < 0.01) at 2 h, peaked at 8 h, and returned to basal levels by 24 h (Fig. 1B). In contrast, there was a significant (p < 0.01) reduction of FLIPL at 2 h (Fig. 1D), although FLIPL protein was increased at 8 and 12 h (Fig. 1B). To determine whether these observations were unique to TNFα, macrophages were incubated with LPS to activate the TLR4 pathway. The effects on FLIPL and FLIPS were the same as observed with TNFα (Fig. 1, A–D). These observations suggest that a regulatory mechanism at protein level is involved in reducing the intracellular level of FLIPL following activation with TNFα or LPS and that these effects were reversed by 8 h.

FIGURE 1.

TNFα- and LPS-mediated regulation of FLIP. A and B, recombinant human TNFα (R&D, Minneapolis, MN) or LPS (Sigma) induces FLIPL and FLIPS. Macrophages were incubated with TNFα or LPS (10 ng/ml), and the cells were harvested at the indicated time points and employed to determine the level of FLIPL and FLIPS mRNA by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (A) and protein by immunoblot analysis (B). The results are representative of four independent experiments. C and D, FLIPL is reduced at 2 h. The expression of FLIPL and FLIPS mRNA (C) and protein (D) in response to incubation with TNFα or LPS at 2 h, is presented as the means ± S.E. of four independent experiments. The data in D represent the expression of FLIP, determined by densitometry normalized with β-actin. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared cells treated with control medium (None). E and F, NF-κB activation regulates TNFα induced FLIP. Macrophages were infected with control (Ad-CMV) or super repressor IκBα (Ad-IκBα) expressing vectors (multiplicity of infection of 100) for 24 h. Following the addition of TNFα the cells were harvested at the indicated time points, and the expression of FLIPL and FLIPS at mRNA (E) and protein by immunoblot analysis (F) was determined. The results presented are representative of two independent experiments.

NF-κB activation is one of the pathways known to contribute to the expression of FLIP (10, 11). Therefore, macrophages were infected with an adenoviral vector expressing a super repressor IκBα (Ad-IκBα) to characterize the effects of the inhibition of NF-κB activation on the expression of FLIP. The ectopic expression IκBα dramatically suppressed the TNFα-induced (Fig. 1, E and F) and LPS-induced (data not shown) FLIPL and FLIPS at both the mRNA (Fig. 1E) and protein (Fig. 1F) levels. Compared with its basal level in the presence of IκBα alone, at 2 h FLIPL protein was reduced by TNFα when IκBα was expressed, suggesting that the activation induced reduction of FLIPL also occurred when NF-κB activation was suppressed. Of note, the suppression of NF-κB activation in macrophages by infection with the Ad-IκBα for 24 h did not suppress the constitutive expression of FLIPL and FLIPS mRNA (Fig. 1E) or the expression of FLIPL protein (Fig. 1F). These observations demonstrate that TNFα- and LPS-induced FLIP in macrophages is predominantly regulated transcriptionally and that the basal levels FLIPL and FLIPS may be regulated by pathways other than NF-κB.

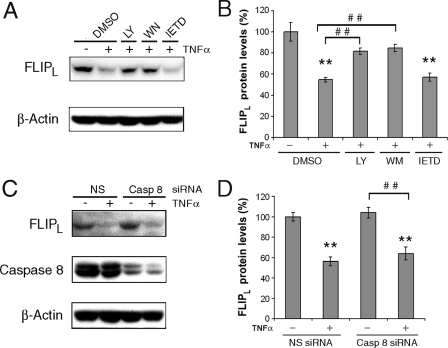

PI3K Is Involved in TNFα-mediated Degradation of FLIPL— Besides activating the NF-κB pathway, TNFα and LPS also activate the MAPK, PI3K/Akt-1, and protein kinase C signaling pathways (34, 35). Because additional studies demonstrated that the reduction of FLIPL was more pronounced at 1 h (40–60%) compared with 2 h (30–40%, p < 0.02), the 1-h time point was employed to define the mechanism for the reduction of FLIPL. The reduction of FLIPL induced by TNFα at 1 h was not observed when macrophages were co-incubated with the PI3K inhibitors LY 294002 (20 μm) or wortmannin (200 nm) (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL was still present when the macrophages were co-incubated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 μm) or the protein kinase C inhibitors bisindolylmaleimide III (20 μm) or bisindolylmaleimide VIII (10 μm) (data not shown). The experiments were also performed to determine whether the reduction of FLIPL may be due to caspase activation, because caspase 8 may form heterodimers with FLIPL (55kDa), processing FLIPL into p43, p22, and p12 fragments (36, 37). Treatment with TNFα alone resulted in very little p43 FLIP (data not shown). Additionally, incubation of macrophages with caspase 8 inhibitor IETD prior to the addition of TNFα failed to prevent the reduction of FLIPL (Fig. 2, A and B). Further, the forced reduction of caspase 8 by a specific siRNA failed to protect FLIPL from TNFα-induced reduction (Fig. 2, C and D). These observations suggest that the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL was mediated through the PI3K pathway and that activated caspase 8 was not responsible.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of PI3K, but not caspase 8, suppresses the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL. A and B, macrophages were incubated for 30 min with LY294002 (20 μm), wortmannin (100 nm), IETD (20 μm) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or control DMSO and then incubated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 1 h. The cells were harvested, and whole cell lysates were employed for immunoblot analysis employing anti-FLIP and β-actin antibodies. C and D, macrophages were transfected with 100 nm caspase 8 or nonspecific (NS) siRNA for 48 h then and then incubated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 1 h. Cell lysates were employed for immunoblot analysis. B and D, the summaries of three independent experiments are presented as the means ± S.E. of immunoblots. The bars represent the expression of FLIPL relative to β-actin determined by densitometry. **, p < 0.01 compared the NS siRNA in the absence of TNFα; ##, p < 0.01 compared with the indicated treatments.

Akt Mediates the TNFα-induced Reduction of FLIPL—Because Akt-1 (Akt) is downstream of PI3K, the experiments were performed to determine the role of Akt in the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL. Employing macrophages, TNFα induced the activation of Akt, determined with an antibody specific for phosphorylation of serine 473 of Akt, and LY 294002 suppressed this activation (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained for LPS (data not shown). To confirm the role of Akt, macrophages were infected with an adenoviral vector expressing a dominant negative form of Akt (Ad-DN-Akt), previously demonstrated to suppress Akt activity (29, 38), or a CMV control vector (Ad-CMV) prior to the addition of TNFα. Following infection with the Ad-CMV vector, incubation with TNFα resulted in a 54% reduction (p < 0.01) of FLIPL at 1 h, whereas no reduction of FLIPL was noted in cells expressing the DN-Akt (Fig. 3, B and C). To more specifically examine the role of Akt, siRNA was employed to transfect macrophages. Overall there was a minor increase of FLIPL in macrophages transfected with the Akt-specific siRNA, compared with the nonspecific siRNA (Fig. 3, D and E). Consistent with the observations obtained employing the chemical inhibitors and the DN Akt, the forced reduction of Akt (Fig. 3D) prevented the reduction of FLIPL induced by incubation with TNFα (Fig. 3E). These observations demonstrate that Akt is necessary for the TNFα-induced suppression of FLIPL.

FIGURE 3.

Akt-1 mediates the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL. A, TNFα activates PI3K/Akt signaling detected by increasing Akt phosphorylation at serine 473. Macrophages were treated with 10 ng/ml of TNFα for the indicated times. Akt serine 473 phosphorylation was detected by Western blot analysis. Total Akt and β-actin were presented as controls. B and C, macrophages were infected with an adenoviral vector expressing a dominant negative Akt (DN-AKT) or a CMV control vector for 24 h prior to the addition of TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 1 h. The results of a representative immunoblot (B) and the summary (means ± S.E.) of three independent experiments (C) are presented. D and E, the forced reduction of Akt protects against the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL. The macrophages were transfected with 100 nm Akt1 or nonspecific (NS) siRNA for 48 h then the cells were incubated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 1 h. The results of a representative immunoblot (D) and the summary (means ± S.E.) of three independent experiments (E) are presented. **, p < 0.01 between the indicated groups.

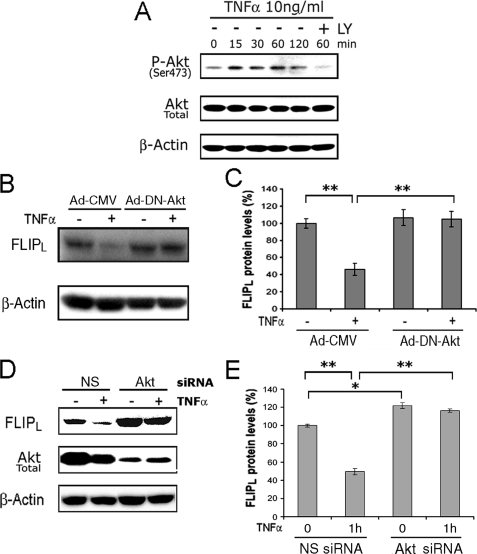

Akt Promotes TNFα-induced Caspase 8 and NF-κB Activation and Increased FLIP mRNA—Experiments were performed to determine the relevance of the Akt-mediated reduction of FLIPL, by examination of caspase 8 activation. When macrophages were transfected with nonspecific siRNA, TNFα induced caspase 8-like activity at 1 h, which returned to base line by 4 h (Fig. 4A). No apoptosis, defined by DNA fragmentation, was observed at 16 h (data not shown). In contrast, the forced reduction of Akt prevented the induction of caspase 8-like activity (Fig. 4A). To determine the biological relevance of the caspase 8-like activity, NF-κB activation was measured by examining IκBα by immunoblot analysis. TNFα resulted in the reduction of IκBα at 15 and 30 min, which returned to base line by 60 min (Fig. 4, B and C). The suppression of caspase 8-like activity by IETD (Fig. 4B) or the forced reduction of caspase 8 by siRNA (Fig. 4C) resulted in the attenuation of NF-κB activation. Because NF-κB activation is responsible for the TNFα-mediated induction of FLIP, the effect of caspase inhibition on the expression of FLIP mRNA was examined. Both IETD and caspase 8 siRNA resulted in the significant (p < 0.05-0.01) reduction of both FLIPL and FLIPS mRNA at 1 and 2 h (Fig. 4, D and E). Therefore, the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL promotes NF-κB activation, which in turn enhances the expression of FLIPL and FLIPS mRNA.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of caspase 8 activation attenuated NF-κB activation. Macrophages were transfected with 100 nm Akt-1 or nonspecific (NS) siRNA for 48 h and then incubated with TNFα for 1 or 4 h, the cells were isolated, and the lysates were examined for caspase 8-like activity (A). Macrophages were incubated for 30 min with IETD (20 μm) or control DMSO (B and D), and then incubated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for indicated time. The harvested samples were subjected to immunoblot (B) and quantitative PCR analysis (D). C and E, macrophages were transfected with 100 nm caspase 8 or nonspecific (NS) siRNA for 48 h and then incubated with TNFα. Cell samples were employed for immunoblot (C) and quantitative PCR analysis (E). The summaries of three (A) or two (D and E) independent experiments are presented. **, p < 0.01 in A compared with the indicated treatments. */#, p < 0.05; **/##, p < 0.01 in D and E compared the control group at the same time point.

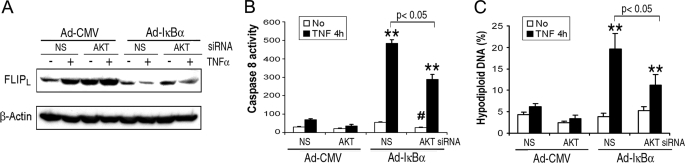

The Forced Reduction of Akt Suppresses TNFα-induced Caspase 8 Activation and Apoptosis When NF-κB Is Suppressed— Next the role of Akt in regulation FLIPL and caspase 8-like activity was examined when NF-κB activation was suppressed. Macrophages were transfected with nonspecific or Akt siRNA and then infected with a control or a super repressor IκBα expressing adenoviral vectors. When NF-κB activation was suppressed, the forced reduction of Akt diminished the reduction of FLIPL induced by TNFα, compared with transfection with nonspecific siRNA (Fig. 5A). The forced reduction of Akt also lessened the TNFα-induced caspase 8-like activity and DNA fragmentation (Fig. 5, B and C) observed when NF-κB activation was suppressed. The forced reduction of Akt resulted in a minor but significant (p < 0.05) reduction of the basal caspase 8-like activity when IκBα was expressed ectopically, and the fold induction of caspase 8-like activity was similar in the presence or absence of Akt siRNA (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the Akt-mediated reduction of FLIPL, promotes TNFα-induced caspase 8 activation and subsequent apoptosis, independent of NF-κB.

FIGURE 5.

The forced reduction of Akt reduced TNFα-induced caspase 8 activation and cell apoptosis. A, macrophages were transfected with 100 nm Akt-1 or nonspecific (NS) siRNA for 48 h and then infected with a multiplicity of infection of 100 of Ad-IκBα or the Ad-CMV control vector for 24 h. After incubation with TNFα (10 ng/ml) or control medium for 4 h, the cells were harvested the lysates examined by immunoblot (A), and for caspase 8-like activity (B), and for apoptosis (hypodiploid DNA, C). The results are the means ± S.E. of three (B) or two (C) independent experiments, performed in duplicate. **, p < 0.01 versus control treatment; #, in B, p < 0.05 versus Ad-IκBα/NS siRNA/no TNFα.

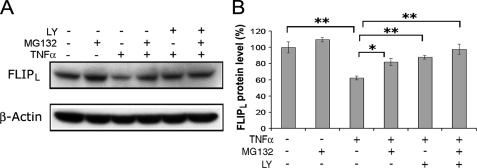

The Proteasome Participates in the TNFα-triggered Reduction of FLIPL—Because the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway contributes to the degradation of FLIPL (17, 18, 21, 39–41), studies were performed to determine the effect of proteasomal inhibition on the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL. Macrophages were preincubated with LY294002 (20 μm) and/or MG132 (10 μm), a cell-permeable proteasome inhibitor, for 30 min prior to the addition of TNFα. Incubation with TNFα alone resulted in the reduction of FLIPL (p < 0.01), whereas preincubation MG132 or LY294002 or the combination of both resulted in significant (p < 0.05 to 0.01) protection against the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL (Fig. 6). There was no difference noted in the protection provided by MG132 or LY294002 employed alone or in combination. These results support the role of the proteasome in the TNFα-mediated reduction of FLIPL and suggest that PI3K/Akt-1 signaling promotes the proteasomal degradation of FLIPL.

FIGURE 6.

The proteasomal pathway participates in TNFα-triggered reduction of FLIPL. Macrophages were preincubated with DMSO, LY294002 (20 μm) and MG132 (10 μm) for 30 min prior to the addition of TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 1 h. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis. The results of a representative immunoblot (A) and the summary of 4 independent experiments (B) are presented. FLIPL assessed by densitometry was normalized with β-Actin. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with the groups indicated.

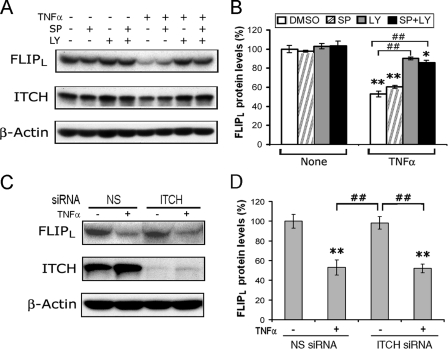

Itch Does Not Contribute to the Reduction of FLIPL in Macrophages—A recent report (21) demonstrated that TNFα accelerates FLIPL turnover through JNK-mediated phosphorylation and activation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch. To determine whether JNK was involved in the TNFα-induced degradation of FLIPL, macrophages were preincubated with the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (20 μm), LY294002 (20 μm), or the combination of both for 30 min prior to incubation with TNFα. Preincubation with the JNK inhibitor, at a concentration that effectively suppressed JNK (42, 43), had no effect on the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL and the combination of the JNK and PI3K inhibitors was not different from PI3K inhibition alone (Fig. 7, A and B). To examine the specific role of Itch, macrophages were transfected with nonspecific or Itch-specific siRNA. The forced reduction of Itch (Fig. 6C) did not protect against the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL (Fig. 7, C and D). These observations do not provide evidence that the JNK-Itch pathway was involved in the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL observed at 1 h in macrophages.

FIGURE 7.

The TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL is not mediated through JNK-ITCH signaling. A and B, JNK inhibition does not prevent TNFα induced FLIPL reduction. Macrophages were preincubated with DMSO, SP600125 (20 μm), or LY294002 (20 μm) as indicated for 30 min prior to the addition of TNFα (10 ng/ml) or control medium, which were incubated for 1 h. The cells were harvested, and the lysates were employed for immunoblot analysis employing antibodies to FLIP, Itch, and β-actin. In A is a representative blot, and B shows the means ± S.E. of four independent experiments. C and D, the forced reduction of Itch does not prevent the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL. Macrophages were transfected with 50 nm Itch siRNA or nonspecific siRNA for 48 h, treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 1 h, and harvested, and the cell extracts were examined by immunoblot analysis for FLIPL, Itch, and β-actin. A representative immunoblot (C) and the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments (D) are presented. **, represents p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 compared with DMSO or medium controls without TNFα; ##, p < 0.01 between the groups indicated.

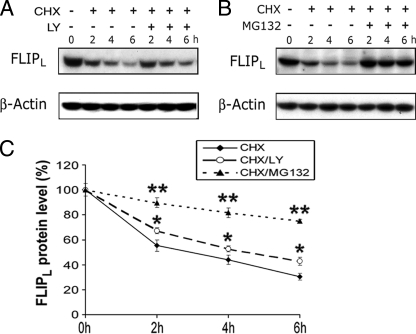

PI3K Pathway Has Minimal Effects on FLIPL Turnover in the Absence of Activation—The studies employing Akt siRNA suggest a role for the PI3K/Akt pathway in the constitutive expression of FLIPL. Therefore, experiments were performed to determine the role of constitutive PI3K in the turnover of FLIPL in the absence of activation with TNFα or LPS. The protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX, 10 μg/ml) was utilized to block new protein synthesis by macrophages. Following treatment with CHX, there was a steady loss of FLIPL when examined between 2 and 6 h (Fig. 7, A–C). Inhibition of the PI3K pathway with LY294002 in the presence of CHX reduced FLIPL turnover by about 19% at 6 h compared with CHX alone (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 suppressed the reduction of FLIPL by 64% at 6 h compared with CHX alone (Fig. 8, B and C). These observations demonstrate that in the absence of activation with TNFα or LPS, the contribution of the PI3K pathway to the turnover of FLIPL is limited.

FIGURE 8.

In the absence of activation, inhibition of the PI3K pathway minimally affects FLIPL turnover. Macrophages were incubated with CHX (10 μg/ml) alone or in the presence of LY294002 or MG132. The cells were harvested between 0 and 6 h, and cell extracts were employed for immunoblots that were probed with antibodies to FLIPL and β-actin (A and B). Changes in the levels of FLIPL were assessed by densitometry, which was normalized with β-actin, and the results (means ± S.E.) of two to four experiments are presented in C. *, represents p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with CHX alone.

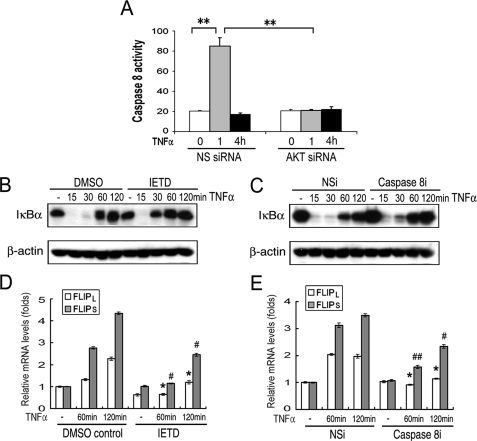

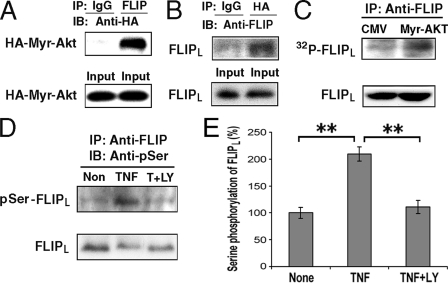

Akt Physically Interacts with FLIPL and Results in FLIPL Serine Phosphorylation—To determine the mechanism by which TNFα and LPS trigger the reduction of FLIPL, experiments were performed to determine whether FLIPL and activated Akt are capable of physically interacting within the cell. Macrophages were co-infected with adenoviral vectors expressing activated Akt (HA-tagged Myr-Akt) and FLIPL, and the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLIP (Fig. 9A) or anti-HA (Fig. 9B) antibodies and then subjected to immunoblot analysis. FLIPL and Akt were able to co-immunoprecipitate, suggesting that activated Akt physically interacts with FLIPL (Fig. 9, A and B), either directly or through an intermediary protein in a larger complex.

FIGURE 9.

Akt physically interacts with FLIPL and results in FLIPL serine phosphorylation. A and B, FLIPL co-immunoprecipitates with Akt-1. Macrophages were co-infected with adenoviral vectors expressing HA-Myr-Akt and FLIPL (multiplicity of infection of 50 for each) for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated employing anti-FLIP (A) or anti-HA (B) antibodies or control IgG and then subjected to immunoblot analysis. The membranes were probed with anti-HA antibody (A) and anti-FLIP antibodies (B). C, activated Akt increases FLIPL phosphorylation. Macrophages were infected with CMV empty vector or a vector expressing Myr-Akt for 24 h. The cells were then incubated with [32P]orthophosphate for 2 h, and FLIPL was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLIP antibody and examined following SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylated FLIPL was detected by autoradiography. The protein lysates of each sample, served as loading controls, following immunoblot analysis for FLIPL (lower panel). This result is representative of two independent experiments. D and E, TNFα increased FLIPL protein serine phosphorylation. Macrophages were treated with TNFα alone or TNFα plus LY294002 for 1 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLIP antibody and examined by immunoblot analysis probing with an anti-phosphoserine antibody (D). The membranes were then stripped and reprobed with anti-FLIP antibody (D, lower panel). The results of three independent experiments quantified by densitometry are presented in E. **, p < 0.01 between the identified groups.

Because Akt is a serine/threonine kinase and its function is based on phosphorylation of down stream target molecules, experiments were performed to determine whether activated Akt was capable of phosphorylating FLIPL. Macrophages were infected with an adenoviral vector expressing constitutively activated Akt (Myr-Akt) and then incubated in vivo with [32P]orthophosphate. The expression of the Myr-Akt in macrophages increased FLIPL phosphorylation (Fig. 9C). Employing the Scansite Web Program (44), a putative Akt phosphorylation site was detected at serine 273, which is unique for FLIPL and is not included in FLIPS. Therefore, experiments were performed to determine whether stimulation with TNFα promoted FLIPL serine phosphorylation. Lysates from macrophages that had been incubated with TNFα in the presence or absence of LY294002 were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLIP antibody, and the immunoblots were probed with anti-phosphoserine and anti-FLIP antibodies (Fig. 9D). TNFα significantly (p < 0.01) increased the serine phosphorylation of FLIPL, which was prevented (p < 0.02) by suppression of the PI3K pathway (Fig. 9E). These observations suggest that the PI3K/Akt-1-mediated phosphorylation of FLIPL may contribute to its reduction following macrophage activation.

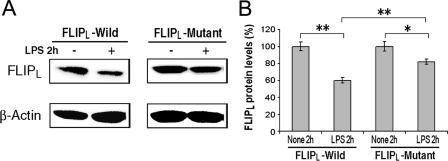

FLIPL Serine 273 to Alanine Substitution (S273A) Results in Resistance to Reduction by LPS—To determine whether serine 273 was critical for the activation-induced reduction of FLIPL, retroviral vectors expressing wild type or S273A FLIPL were employed to stably infect the RAW267.4 macrophage cell line. The ectopically expressed wild type and S293A mutant FLIPL were detected at comparable levels (Fig. 10A), and the expression of the endogenous FLIPL was much weaker than the ectopically expressed protein and cannot be seen on the blots at this exposure. Treatment with LPS for 2 h resulted in an approximately 40% reduction (p < 0.01) of the wild type FLIPL (Fig. 10). Although LPS reduced the S273A mutant FLIPL somewhat, the reduction observed with the wild type FLIPL was significantly greater (p < 0.01) than observed with the S273A mutant (Fig. 10B). These observations demonstrate that the LPS-induced reduction of FLIPL is mediated, at least in part, through the Akt-mediated phosphorylation of serine 273 of FLIPL.

FIGURE 10.

Serine 273 to alanine mutation suppresses LPS-induced reduction of FLIPL. Wild type and S273A mutant FLIPL were stably expressed in RAW264.7 cells, which were treated with LPS (10 ng/ml) or control medium for 2 h. The cell lysates were employed for immunoblot analysis probing with antibodies to FLIPL and to β-actin (A). The summary (means ± S.E.) of three independent experiments quantified by densitometry is presented in B. *, represents p < 0.05; **, < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The expression of FLIP is critical for macrophage survival because these cells express both Fas and FasL and are the principal source of TNFα (27). In the absence of an additional stimulus, the forced reduction of FLIP induced caspase activation and apoptosis of macrophages, mediated by Fas-FasL interactions (27). The current study demonstrates that TNFα not only activates NF-κB, which leads to the expression of flip mRNA resulting in an increase of both FLIPL and FLIPS, but also activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, which leads to the reduction of FLIPL protein at 1–2 h. These observations identify a novel mechanism whereby activation by TNFα initiates a potential death promoting signal through Akt and suggest that this effect is counteracted by the activation of NF-κB, which rescues the cell by the rapid induction of FLIPS. Similarly, in short term activated T cells, the transient induction of FLIPS protected against death receptor-mediated apoptosis (45). Supporting the relevance of this process, the reduction of FLIPL by TNFα was accompanied by the short term induction of caspase 8-like activity, which promoted the activation of NF-κB and enhanced the expression of FLIPL and FLIPS, which was associated with protection against apoptosis. The activation-induced reduction of FLIPL is not unique to TNFα, because the TLR4 ligand LPS also resulted in the Akt-mediated reduction of FLIPL.

TNFα and LPS have been shown to induce the NF-κB-mediated expression of FLIPL and FLIPS in a variety of cell types, promoting inducible resistance to death receptor signaling (10, 11, 46). Consistent with these observations, our data with primary human macrophages demonstrate that TNFα and LPS result in the rapid induction of mRNA for both FLIPL and FLIPS, which was mediated through NF-κB activation. Of interest, the expression of the super-repressor IκBα for 24 h in the absence of TNFα or LPS resulted in no reduction of FLIP mRNA or protein, despite the fact that NF-κB is constitutively activated in macrophages (47). Consistent with this observation, the basal expression of FLIPL mRNA and protein in RelA-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts and RelA-deficient hepatocytes is not different from the wild type controls (48, 49). These observations suggest that mechanisms other than NF-κB, such as PI3K/Akt, or MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (14–16, 50–53), may contribute to basal expression of FLIP in macrophages.

Employing chemical inhibitors, DN-Akt and an Akt-specific siRNA, we demonstrate in this study that Akt mediated the TNFα-induced reduction of FLIPL. Earlier observations, documenting the ability of Akt to up-regulate the expression of FLIPL (14–16, 53), appear to contradict this interpretation. However, the differences may relate to the timing and mechanism of activation of Akt. Neither LY294002 nor DN-Akt had an effect on the basal level of mRNA of FLIPL or FLIPS in macrophages, suggesting that the PI3K/Akt pathway, although constitutively activated in in vitro differentiated macrophages (29), does not regulate the constitutive transcription of flip in macrophages (data not shown). However, infection of macrophages with an adenoviral vector expressing activated Akt for 24 h resulted in the induction of mRNA and protein for FLIPL and FLIPS, which was mediated through the activation of NF-κB (data not shown), as previously described (54). In other studies, the activation of Akt employing bioactive lipids, endothelial growth factor, or Notch-1 resulted in the induction of FLIPL, although the effects at early time points were not examined (15, 16, 53). These observations suggest that the PI3K/Akt pathway does not contribute to the basal expression of FLIP mRNA in macrophages, in contrast to the observations in a variety of tumor cells (14).

The ability of the PI3K/Akt pathway to promote the degradation of FLIPL was, at least in part, mediated by the phosphorylation of FLIPL on serine 273 in the caspase 8-like domain. In macrophages, activated Akt physically interacted with FLIPL, resulting in the serine phosphorylation of FLIPL. Examination of the sequence of FLIPL revealed a single putative Akt phosphorylation site at serine 273 that is not present in FLIPS. Supporting the importance of this site, mutation of serine 273 to alanine significantly suppressed the LPS-induced reduction of FLIPL. Further supporting the importance of this site, TNFα and LPS resulted in the induction of FLIPS mRNA, without evidence of degradation at 1–2 h. Other studies have documented the phosphorylation of FLIPL. The bile acid glycochenodeoxycholate phosphorylated FLIPL and FLIPS in a protein kinase C-dependent manner, decreasing the association of both isoforms with Fas-associated death domain, thereby decreasing recruitment to the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand death-inducing signal complex, sensitizing the cells to TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis (55). In contrast, in a Fas ligand-resistant cell line, the phosphorylation of FLIPL by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II resulted in increased recruitment of the p43 intermediate form of FLIPL to the Fas death-inducing signal complex, resulting in resistance to Fas ligand-mediated apoptosis (56). Together, these observations demonstrate that phosphorylation of FLIPL at different locations may affect its localization within the cell (55, 56) or its turnover.

The reduction of FLIPL at 1–2 h was not due to processing by caspase activation because the addition of the caspase 8 inhibitor IETD or forced reduction of caspase 8 by specific siRNA did not prevent the reduction of FLIPL. This observation is consistent with an earlier study that demonstrated that caspase inhibition did not prevent the reduction of FLIPL in endothelial cells induced by treatment with LPS in the presence of cycloheximide (57). Even though the caspase 8-like activity was detected 1 h after the addition of TNFα, our observations suggest that this activity was the result, rather than the cause, of reduction of FLIPL. Numerous studies have documented the ubiquitinylation of FLIPL, identifying this pathway as a key regulator of the level of FLIPL (17, 18, 21, 40, 41). Relevant to our observations, Fas ligation of an epithelial cell line, in the absence of an additional treatment, resulted in the degradation of FLIPL which was mediated through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (17). Our data suggest that activation of Akt promotes the proteasomal degradation of FLIPL, because inhibition of the PI3K/Akt and the proteasomal pathways equally protected macrophages from TNFα-induced cell death.

Recently, TNFα was shown to promote the degradation of FLIPL through the activation of JNK1, which resulted in the phosphorylation and activation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch, which then ubiquitinated FLIPL promoting its proteasomal degradation. In this system, the prolonged activation of JNK1 was necessary and was observed when the activation of NF-κB was prevented by genetic deletion, suppression of NF-κB activation, or suppression of protein synthesis with cycloheximide (21). The suppression of NF-κB resulted in inhibition of MAPK phosphatases (58), which were necessary for the normal attenuation of TNFα-induced JNK activation. Additionally, FLIPL was also shown to bind MKK7 and suppress the prolonged activation of JNK (48). In contrast, in human macrophages, the reduction of FLIPL induced by TNFα or LPS was observed even in the absence of inhibition of NF-κB or the use of cycloheximide, supporting the potential biological relevance of our observations. Further, we did not find evidence for the involvement of JNK or Itch because neither the JNK inhibitor SP600125 nor the forced suppression of Itch prevented the reduction of FLIPL in macrophages following stimulation with TNFα. The difference between the studies is likely due to the fact that the reduction of FLIPL observed in our study occurred in the absence of the inhibition of NF-κB, cycloheximide, or the prolonged activation of JNK. Additionally there may be important cell type-specific differences because our study focused on macrophages, whereas hepatocytes and mouse embryonic fibroblasts were the focus of the study that identified the JNK/Itch pathway (21).

Species variation may also account for the differences in the mechanism for the TNFα-mediated reduction of FLIPL. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (48) and murine hepatocytes (49) deficient in NF-κB p65 express normal levels of FLIPL but undergo apoptotic cell death following the addition of TNFα. The cell death is associated with the reduction of FLIPL (48, 49). However, in these cell types, apoptosis and the reduction of FLIPL is mediated through the activation of caspase 8 (48, 49). We also examined murine bone marrow-derived macrophages. In the absence of the inhibition of NF-κB, the addition of LPS resulted in the reduction of FLIPL, which was mediated through caspase 8 activation, and suppression of the PI3K/Akt pathway did not prevent the reduction of FLIPL (data not shown). One potential explanation for the lack of PI3K/Akt involvement in murine cells may be that the murine FLIPL sequence does not contain a putative Akt phosphorylation site. In summary there are at least three mechanisms by which TNFα induces the post-translational degradation of FLIPL, which employs the PI3K/Akt-, JNK1/Itch-, and caspase 8-mediated pathways, and they may be species-, cell type-, and context-specific.

The activation-induced reduction of FLIPL provides a potential mechanism for the initiation of cell death by which macrophages, which are not capable of adequately responding, may be eliminated following exposure to environmental stress. The post-translational reduction of FLIPL may be an integral event in the many studies that have characterized death receptor-mediated cell death when NF-κB activation is suppressed (59, 60). It is possible that the activation-induced reduction of FLIPL may be involved in macrophage apoptosis induced following microbial infection. Macrophages infected with Yesinia enterocolitica, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or Escherichia coli may undergo apoptosis (61–64). Following infection, NF-κB activation was suppressed, and TNFα and TLR4 ligation contributed to the apoptosis observed (61–64), supporting a potential role for activation-induced reduction of FLIPL in this setting. It is also possible that the short term activation of caspase 8 may have a nonapoptotic function. The activation of caspase 8 contributes to differentiation of macrophages from monocytes and may also promote T cell receptor-mediated NF-κB activation of T cells and LPS-induced NF-κB activation of B cells (65–68). In macrophages the activation-induced reduction of FLIPL resulted in caspase 8 activation, which promoted NF-κB activation and the rapid induction of FLIP. In summary, this dynamic regulation of FLIP following a potential death-inducing signal determines the fate of the macrophage and may provide a therapeutic target in strategies directed at promoting death receptor-mediated apoptosis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AR049217 and AR048269.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; siRNA, small interfering RNA; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; FBS, fetal bovine serum; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DN, dominant negative; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; HA, hemagglutinin; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; CHX, cycloheximide; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

References

- 1.Irmler, M., Thome, M., Hahne, M., Schneider, P., Hofmann, K., Steiner, V., Bodmer, J.-L., Schroter, M., Burns, K., Mattmann, C., Rimoldi, D., French, L. E., and Tschopp, J. (1997) Nature 388 190-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasper, D. M., Vaillancourt, J. P., Hadano, S., Houtzager, V. M., Seiden, I., Keen, S. L. C., Tawa, P., Xanthoudakis, S., Nasir, J., Martindale, D., Koop, B. F., Peterson, E. P., Thornberry, N. A., Huang, J., MacPherson, D. P., Black, S. C., Hornung, F., Leonardo, M. J., Hayden, M. R., Roy, S., and Nicholson, D. W. (1998) Cell Death Differ. 5 271-288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh, W.-C., Itie, A., Elia, A. J., Ng, M., Shu, H.-B., Wakeham, A., Mirtsos, C., Suzuki, N., Bonnard, M., Goeddel, D. V., and Mak, T. W. (2000) Immunity 12 633-642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djerbi, M., Darreh-Shori, T., Zhivotovsky, B., and Grandien, A. (2001) Scand. J. Immunol. 54 180-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oyarzo, M. P., Medeiros, L. J., Atwell, C., Feretzaki, M., Leventaki, V., Drakos, E., Amin, H. M., and Rassidakis, G. Z. (2006) Blood 107 2544-2547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day, T. W., Najafi, F., Wu, C. H., and Safa, A. R. (2006) Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 1551-1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longley, D. B., Wilson, T. R., McEwan, M., Allen, W. L., McDermott, U., Galligan, L., and Johnston, P. G. (2006) Oncogene 25 838-848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlman, H., Pagliari, L. J., Liu, H., Koch, A. E., Haines, G. K., III, and Pope, R. M. (2001) Arthritis Rheum. 44 21-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valente, G., Manfroi, F., Peracchio, C., Nicotra, G., Castino, R., Nicosia, G., Kerim, S., and Isidoro, C. (2006) Br. J. Haematol. 132 560-570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Micheau, O., Lens, S., Gaide, O., Alevizopoulos, K., and Tschopp, J. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 5299-5305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai, S., Liu, H., Chen, K. H., Eksarko, P., Perlman, H., Moore, T. L., and Pope, R. M. (2004) Arthritis Rheum. 50 3844-3855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perlman, H., Pagliari, L. J., Nguyen, N., Bradley, K., Liu, H., and Pope, R. M. (2001) Eur. J. Immunol. 31 2421-2430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suhara, T., Mano, T., Oliveira, B. E., and Walsh, K. (2001) Circ. Res. 89 13-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panka, D. J., Mano, T., Suhara, T., Walsh, K., and Mier, J. W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 6893-6896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sade, H., Krishna, S., and Sarin, A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 2937-2944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang, Y. C., Kim, K. M., Lee, K. S., Namkoong, S., Lee, S. J., Han, J. A., Jeoung, D., Ha, K. S., Kwon, Y. G., and Kim, Y. M. (2004) Cell Death Differ. 11 1287-1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chanvorachote, P., Nimmannit, U., Wang, L., Stehlik, C., Lu, B., Azad, N., and Rojanasakul, Y. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 42044-42050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukazawa, T., Fujiwara, T., Uno, F., Teraishi, F., Kadowaki, Y., Itoshima, T., Takata, Y., Kagawa, S., Roth, J. A., Tschopp, J., and Tanaka, N. (2001) Oncogene 20 5225-5231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palacios, C., Yerbes, R., and Lopez-Rivas, A. (2006) Cancer Res. 66 8858-8869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poukkula, M., Kaunisto, A., Hietakangas, V., Denessiouk, K., Katajamaki, T., Johnson, M. S., Sistonen, L., and Eriksson, J. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 27345-27355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang, L., Kamata, H., Solinas, G., Luo, J. L., Maeda, S., Venuprasad, K., Liu, Y. C., and Karin, M. (2006) Cell 124 601-613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, Y., and Pope, R. M. (2005) Curr. Pharm. Des. 11 569-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Donnell, R., Breen, D., Wilson, S., and Djukanovic, R. (2006) Thorax 61 448-454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumeng, C. N., Bodzin, J. L., and Saltiel, A. R. (2007) J. Clin. Investig. 117 175-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tacke, F., Alvarez, D., Kaplan, T. J., Jakubzick, C., Spanbroek, R., Llodra, J., Garin, A., Liu, J., Mack, M., van Rooijen, N., Lira, S. A., Habenicht, A. J., and Randolph, G. J. (2007) J. Clin. Investig. 117 185-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon, S. (2007) J. Clin. Investig. 117 89-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perlman, H., Pagliari, L. J., Georganas, C., Mano, T., Walsh, K., and Pope, R. M. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190 1679-1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, H., Ma, Y., Cole, S. M., Zander, C., Chen, K. H., Karras, J., and Pope, R. M. (2003) Blood 102 344-352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, H., Perlman, H., Pagliari, L. J., and Pope, R. M. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194 113-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma, Y., Temkin, V., Liu, H., and Pope, R. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 41827-41834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, H., Ma, Y., Pagliari, L. J., Perlman, H., Yu, C., Lin, A., and Pope, R. M. (2004) J. Immunol. 172 1907-1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, H., Eksarko, P., Temkin, V., Haines, G. K., III, Perlman, H., Koch, A. E., Thimmapaya, B., and Pope, R. M. (2005) J. Immunol. 175 8337-8345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, H., Huang, Q., Shi, B., Eksarko, P., Temkin, V., and Pope, R. (2006) Arthritis Rheum. 54 3174-3181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wajant, H., Pfizenmaier, K., and Scheurich, P. (2003) Cell Death Differ. 10 45-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Neill, L. A., and Bowie, A. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7 353-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medema, J. P., Scaffidi, C., Kischkel, F. C., Shevchenko, A., Mann, M., Krammer, P. H., and Peter, M. E. (1997) EMBO J. 16 2794-2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scaffidi, C., Schmitz, I., Krammer, P. H., and Peter, M. E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 1541-1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujio, Y., and Walsh, K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 16349-16354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue, H., Shiraki, K., Murata, K., Sugimoto, K., Kawakita, T., Yamaguchi, Y., Saitou, Y., Enokimura, N., Yamamoto, N., Yamanaka, Y., and Nakano, T. (2004) Int. J. Mol. Med. 14 271-275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim, Y., Suh, N., Sporn, M., and Reed, J. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 22320-22329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang, S., Shen, H. M., and Ong, C. N. (2005) Mol. Cancer Ther. 4 1972-1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett, B. L., Sasaki, D. T., Murray, B. W., O'Leary, E. C., Sakata, S. T., Xu, W., Leisten, J. C., Motiwala, A., Pierce, S., Satoh, Y., Bhagwat, S. S., Manning, A. M., and Anderson, D. W. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 13681-13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woo, K. J., Park, J. W., and Kwon, T. K. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 342 1334-1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obenauer, J. C., Cantley, L. C., and Yaffe, M. B. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3635-3641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueffing, N., Schuster, M., Keil, E., Schulze-Osthoff, K., and Schmitz, I. (2008) Blood 112 690-698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kreuz, S., Siegmund, D., Scheurich, P., and Wajant, H. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 3964-3973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pagliari, L. J., Perlman, H., Liu, H., and Pope, R. M. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 8855-8865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakajima, A., Komazawa-Sakon, S., Takekawa, M., Sasazuki, T., Yeh, W. C., Yagita, H., Okumura, K., and Nakano, H. (2006) EMBO J. 25 5549-5559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geisler, F., Algul, H., Paxian, S., and Schmid, R. M. (2007) Gastroenterology 132 2489-2503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davies, C. C., Mason, J., Wakelam, M. J., Young, L. S., and Eliopoulos, A. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 1010-1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nam, S. Y., Jung, G. A., Hur, G. C., Chung, H. Y., Kim, W. H., Seol, D. W., and Lee, B. L. (2003) Cancer Sci 94 1066-1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uriarte, S. M., Joshi-Barve, S., Song, Z., Sahoo, R., Gobejishvili, L., Jala, V. R., Haribabu, B., McClain, C., and Barve, S. (2005) Cell Death Differ. 12 233-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skurk, C., Maatz, H., Kim, H. S., Yang, J., Abid, M. R., Aird, W. C., and Walsh, K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 1513-1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ozes, O. N., Mayo, L. D., Gustin, J. A., Pfeffer, S. R., Pfeffer, L. M., and Donner, D. B. (1999) Nature 401 82-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higuchi, H., Yoon, J. H., Grambihler, A., Werneburg, N., Bronk, S. F., and Gores, G. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 454-461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang, B. F., Xiao, C., Roa, W. H., Krammer, P. H., and Hao, C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 7043-7050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bannerman, D. D., Tupper, J. C., Ricketts, W. A., Bennett, C. F., Winn, R. K., and Harlan, J. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 14924-14932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamata, H., Honda, S., Maeda, S., Chang, L., Hirata, H., and Karin, M. (2005) Cell 120 649-661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karin, M., and Lin, A. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3 221-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papa, S., Bubici, C., Zazzeroni, F., Pham, C. G., Kuntzen, C., Knabb, J. R., Dean, K., and Franzoso, G. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13 712-729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keane, J., Balcewicz-Sablinska, M. K., Remold, H. G., Chupp, G. L., Meek, B. B., Fenton, M. J., and Kornfeld, H. (1997) Infect. Immun. 65 298-304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riendeau, C. J., and Kornfeld, H. (2003) Infect. Immun. 71 254-259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haase, R., Kirschning, C. J., Sing, A., Schrottner, P., Fukase, K., Kusumoto, S., Wagner, H., Heesemann, J., and Ruckdeschel, K. (2003) J. Immunol. 171 4294-4303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Albee, L., and Perlman, H. (2006) Inflamm. Res. 55 2-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rebe, C., Cathelin, S., Launay, S., Filomenko, R., Prevotat, L., L'Ollivier, C., Gyan, E., Micheau, O., Grant, S., Dubart-Kupperschmitt, A., Fontenay, M., and Solary, E. (2007) Blood 109 1442-1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sordet, O., Rebe, C., Plenchette, S., Zermati, Y., Hermine, O., Vainchenker, W., Garrido, C., Solary, E., and Dubrez-Daloz, L. (2002) Blood 100 4446-4453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Su, H., Bidere, N., Zheng, L., Cubre, A., Sakai, K., Dale, J., Salmena, L., Hakem, R., Straus, S., and Lenardo, M. (2005) Science 307 1465-1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Misra, R. S., Russell, J. Q., Koenig, A., Hinshaw-Makepeace, J. A., Wen, R., Wang, D., Huo, H., Littman, D. R., Ferch, U., Ruland, J., Thome, M., and Budd, R. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 19365-19374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]