Abstract

Bone is remodeled constantly throughout life by bone-resorbing osteoclasts and bone-forming osteoblasts. To maintain bone volume and quality, differentiation of osteoclasts and osteoblasts is tightly regulated through communication between and within these two cell lineages. Previously we reported that cell-cell interaction mediated by ephrinB2 ligand on osteoclasts and EphB4 receptor on osteoblasts generates bidirectional anti-osteoclastogenic and pro-osteoblastogenic signals into respective cells and presumably facilitates transition from bone resorption to bone formation. Here we show that bidirectional ephrinA2-EphA2 signaling regulates bone remodeling at the initiation phase. EphrinA2 expression was rapidly induced by receptor activator of NF-κB ligand in osteoclast precursors; this was dependent on the transcription factor c-Fos but independent of the c-Fos target gene product NFATc1. Receptor EphA2 was expressed in osteoclast precursors and osteoblasts. Overexpression experiments revealed that both ephrinA2 and EphA2 in osteoclast precursors enhanced differentiation of multinucleated osteoclasts and that phospholipase Cγ2 may mediate ephrinA2 reverse signaling. Moreover, ephrinA2 on osteoclasts was cleaved by metalloproteinases, and ephrinA2 released in the culture medium enhanced osteoclastogenesis. Interestingly, differentiation of osteoblasts lacking EphA2 was enhanced along with alkaline phosphatase, Runx2, and Osterix expression, indicating that EphA2 on osteoblasts generates anti-osteoblastogenic signals presumably by up-regulating RhoA activity. Therefore, ephrinA2-EphA2 interaction facilitates the initiation phase of bone remodeling by enhancing osteoclast differentiation and suppressing osteoblast differentiation.

Bone remodeling maintains bone mass constant during adulthood (1, 2). Resorption of old mineralized bone by osteoclasts is followed by new bone formation by osteoblasts. These processes, consisting of the initiation, transition, and termination phases, are tightly regulated by communication between osteoclasts and osteoblasts (3). Bone resorption is excessive in the most common skeletal diseases such as osteoporosis, but molecular mechanisms that balance bone remodeling are only partially understood.

Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells (MNCs)3 responsible for bone resorption. They originate from the fusion of hematopoietic precursor cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Osteoblasts express the two major membrane-bound proteins required for osteoclast differentiation, macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), and the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL). Soluble forms of M-CSF and RANKL allow us to generate osteoclasts from M-CSF-dependent macrophages (MDMs) in cultures. Downstream signaling pathways ultimately activate critical osteoclastogenic transcription factors such as c-Fos (4) and NFATc1 (5-7). NFATc1 is a target gene product of c-Fos (8) and activates gene expression of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), calcitonin receptor, and ephrinB2.

Ephrin ligands and Eph receptor tyrosine kinases are crucial for migration, repulsion, and adhesion of cells during neuronal, vascular, and intestinal development (9, 10). Both ephrins and Ephs are membrane-bound proteins, which generate bidirectional signaling by interacting with each other. Signaling through ephrins is called “reverse signaling,” whereas signaling through Ephs is called “forward signaling.” Ephrins fall into the following two classes, based on their structural homologies: ephrinAs (ephrinA1-A5), which are glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, and ephrinBs (ephrinB1-B3), which have the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Ephs are also divided into two classes, EphAs (EphA1-A10), which mainly interact with ephrinAs, and EphBs (EphB1-B6), which mainly interact with ephrinBs.

We previously demonstrated that ephrinB2 on osteoclasts mediates inhibitory signals for osteoclast differentiation, whereas EphB4 on osteoblasts mediates stimulatory signals for osteoblast differentiation (11). Recently, it was reported that parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related peptide induce ephrinB2 expression in osteoblasts. Therefore, ephrinB2-EphB4 interaction among osteoblasts might contribute to the anabolic effect of PTH and PTH-related peptide (12). Class A ephrin-Eph members are also expressed in bone. For example, EphA4 may function in chondrocytes and osteoblasts (13). In this study, we focus on the ephrinA and EphA families expressed on osteoclasts and osteoblasts. We show that ephrinA2-EphA2 interaction within osteoclast precursors or between osteoclast and osteoblast precursors enhances osteoclastogenesis while inhibiting osteoblast differentiation. These data reveal that class A ephrins and Ephs regulate the initiation phase of bone remodeling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

In Vitro Differentiation of Osteoclasts and Osteoblasts—Spleen or bone marrow cells were isolated from C57BL/6J mice or from mice lacking c-Fos (Fos KO) (4) and were cultured for 6 h to overnight in α-minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum to harvest nonadherent cells. For stromal cell-free osteoclast formation, nonadherent cells were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well in 6-well plates, 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates, or 2 × 104 cells (unless otherwise indicated) per well in 96-well plates in α-minimal essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum containing 10 ng/ml recombinant human M-CSF (R & D Systems) for 3 days. These M-CSF-dependent macrophages (MDMs) were used as osteoclast precursors. Osteoclast differentiation was induced for 3-4 days in the presence of 10 ng/ml each of recombinant human M-CSF and recombinant mouse RANKL (R & D Systems). For co-cultures with osteoblasts, nonadherent cells were seeded at 105 cells/96 wells with 104 cells/96-well osteoblasts and cultured in the presence of 10-8 m 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 10-7 m dexamethasone. Differentiated osteoclasts were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and with ethanol/acetone (50:50) and then were stained for TRAP activity using a kit (Sigma) with 20 mm tartrate. MDMs were treated with calcineurin inhibitor FK506 (Calbiochem), which blocks nuclear factor of activated T-cell activation, or a broad spectrum matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor BB94 (British Biotech Pharmaceuticals) where indicated. For osteoblast differentiation, calvarial osteoblasts were isolated from wild-type and EphA2-deficient neonatal mice (14) and expanded in α-minimal essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Osteoblast differentiation was induced in the presence of 30 μg/ml ascorbic acid, 10 mm β-glycerophosphate, and 50 ng/ml BMP-2 (R & D Systems). Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and calcium staining were described previously (15). ALP activity and the amount of calcium were measured using kits (LabAssay™ ALP and calcium C, Wako Pure Chemical Industries) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Conventional and Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis—Total RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) were performed as described previously (11). Sequences of RT-PCR primers are listed in supplemental Table 1 or as described previously (11). RT-PCR and qRT-PCR primers for ephrinA2, ephrinB2, NFATc1, and EphA2 were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

Immunoblot Analysis—Proteins prepared from osteoclastogenic or osteoblastogenic cultures were separated on 4-12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (NOVEX) and transferred onto Hybond nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences). Anti-ephrinA2 (R & D Systems), anti-EphA2 specific to intracellular domain (clone D7, Upstate), anti-EphA2 specific to extracellular domain (R & D Systems), anti-vimentin (Chemicon), anti-PLCγ2 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-PLCγ2 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-RhoA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-actin antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used as primary antibodies. Membrane and non-membrane proteins were isolated using a kit (Calbiochem) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The active RhoA was precipitated with rhotekin-RBD GST beads (Cytoskeleton, Inc.).

Immunofluorescence—Femurs were dissected from C57BL/6J mice and decalcified using 10% EDTA (pH 7.6). They were immersed in 20% sucrose and embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetechnical). Embedded tissues were cut into 14-μm longitudinal sections. Anti-ephrinA2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology andR&D Systems), anti-EphA2 (R&D Systems), anti-cathepsin K (Fuji Chemical), and anti-osteocalcin (Alexis Bio-chemicals) antibodies were used as primary antibodies. Then anti-goat Alexa568, anti-rabbit Alexa546, anti-rabbit Alexa647 and anti-mouse Alexa647 antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used as secondary antibodies. Sections were mounted in Vectashield® mounting media containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM510 META, Carl Zeiss).

Luciferase Reporter Assay—RAW264.7 cells were plated at 5 × 104 cells/well in 48-well plates, and 0.2 μg of the luciferase construct, 0.2 μg of a pBabe activator plasmid, and 0.02 μg of β-actin-Renilla internal control were co-transfected using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). A 1.6-kb fragment containing the ephrinA2 promoter and the entire 5′-untranslated region fragment was PCR-amplified from mouse genome using the primers, 5′-AGCATGCAAATGAGGCCTGGTGATG-3′ and 5′-GAGTCTGAGGGTGCAGAGGGCTTCC-3′, and then cloned into pGL3 vector. pGL3 containing 5× TRE (TPA-response element) and pBabe expressing c-Fos or c-Fos∼c-Jun (c-Fos and c-Jun are tethered via a flexible peptide linker) were described previously (16). Luciferase activity was quantified using the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and a MicroLumat Plus (Berthold).

Infection of Cells with Retroviral Vectors—Retroviruses were produced from Plat-E cells (17) and were used to infect cells in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma) and 10 ng/ml M-CSF for 72 h.

Plasmids—An ephrinA2 cDNA was PCR-amplified from RAW264.7 macrophages treated with RANKL for 24 h. The forward primer contained a BamHI and the ATG codon, 5′-GGATCCACCATGGCGCCCGCGCAGCGCCCG-3′, and the reverse primer contained a stop codon and an XhoI, 5′-CGCTCGAGCTAGGAGCCCAGAAGGGACCAC-3′. The PCR product was cloned into retroviral vector pMX-IRES-EGFP. pMX-Fos-IRES-EGFP, pMX-caNFATc1-IRES-EGFP (8), pShuttle-EphA2, pShuttle-EphA2-K646M, pEGFP-EphA2-ΔC (18), pCLXSN-EphA2-GLZ, pCLXSN-EphA2-Myr-GLZ, and pCLXSN-EphA2-Myr-GLZ-K646M (19) were described previously.

Bone Resorption Assay—Bone slices were prepared as described (11). The slices were placed at the bottom of each well, and cells were cultured on top of the slices. The resulting cells were removed in 50 mm NH3OH at 4 °C. The slices were stained with wheat germ agglutinin/lectin/horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) (20) for 1 h and developed in diaminobenzidine solution (Dako). The bone slices were scanned, and the resorbed area per bone slice area was calculated using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Flow Cytometry—MDMs were stained with anti-ephrinA2 (R & D Systems) and anti-goat Alexa647 (Molecular Probes) antibodies. Stained cells were analyzed using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). For cell sorting, retrovirus-infected GFP-positive MDMs were enriched by MoFlo (Beckman Coulter).

RESULTS

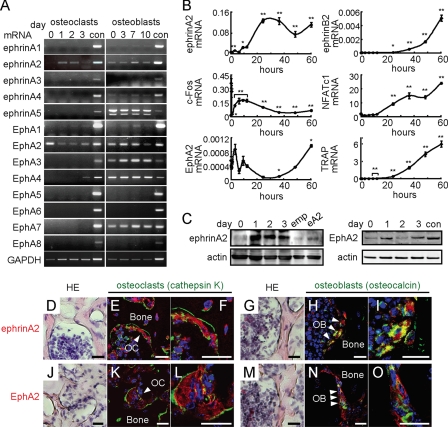

Expression of EphrinA2 and EphA2 in Osteoclast and Osteoblast Precursors—We first analyzed expression of all known members of the ephrinA and EphA families during osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation by RT-PCR. In osteoclasts, ephrinA2 was induced 1 day after RANKL addition, and its receptors EphA2 and EphA4 were also detected in the osteoclast lineage, EphA4 being limited to mature osteoclasts (Fig. 1A). Osteoblasts expressed multiple ephrinAs and EphAs (Fig. 1A). By qRT-PCR analysis, induction of ephrinA2 was detected 10 h after the RANKL addition following c-Fos expression (Fig. 1B). Curiously, EphA2 expression was transiently reduced when ephrinA2 was induced during the early phase of osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 1B). By contrast, ephrinB2, NFATc1, and TRAP were gradually increased and reached maximum levels over 60 h (Fig. 1B). Similar patterns of ephrinA2 and EphA2 expression were observed at protein levels (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, both ephrinA2 and EphA2 were detected in osteoclasts and osteoblasts on the bone surface in vivo (Fig. 1, D-O). These data suggest that ephrinA2 on cells in the osteoclast lineage can interact with EphA2 on osteoclasts in addition to EphAs on osteoblasts.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of ephrinA2 and EphA2 during osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation. A, RT-PCR analysis. MDMs were treated with RANKL, and calvarial osteoblasts were treated with ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate for the indicated days. con, control adult mouse brain. B, qRT-PCR analysis. MDMs were treated with RANKL for 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h. Error bars represent means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus 0 h. C, immunoblot analysis during osteoclast differentiation. Upper panel, ephrinA2. Negative and positive controls were MDMs infected with empty (emp) and ephrinA2-expressing (eA2) retroviruses, respectively. Lower panel, EphA2. con, control adult mouse brain. day, after RANKL addition. D-O, expression of ephrinA2 and EphA2 in bone. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of mouse femurs (D, G, J, and M), and immunofluorescence detection of ephrinA2 (red, E, F, H, and I) and EphA2 (red, K, L, N, and O). Osteoclasts (OC) were identified as multinucleated cells expressing cathepsin K (green, E, F, K, and L). Osteoblasts (OB) were cells expressing osteocalcin (green, H, I, N, and O). Higher magnification of osteoclasts or osteoblasts in E, H, K, and N are shown in F, I, L, and O, respectively. Nuclei are shown in blue (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Scale bars, 20 μm.

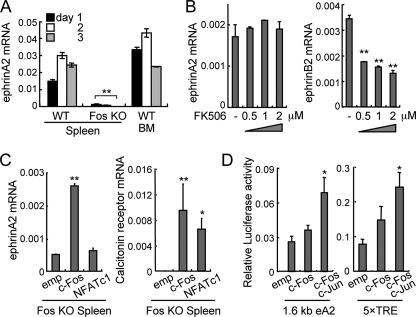

c-Fos-dependent, NFATc1-independent Expression of EphrinA2—The AP-1 component c-Fos and its target NFATc1 are both essential transcriptional factors for osteoclastogenesis. To examine whether c-Fos could regulate ephrinA2 expression, we prepared MDMs from c-Fos KO splenocytes. By qRT-PCR analysis, we found that RANKL-induced ephrinA2 expression was abolished in Fos KO MDMs, suggesting that ephrinA2 is a direct or indirect transcriptional target of c-Fos (Fig. 2A). Next, we prepared wild-type MDMs and treated them with increasing concentrations of the calcineurin inhibitor FK506, which blocks NFATc1 activation. The presence of FK506 did not affect RANKL-induced ephrinA2 (Fig. 2B, left panel), whereas FK506 suppressed ephrinB2 expression in a dose-dependent manner, as expected (11) (Fig. 2B, right panel). Consistently, ephrinA2 expression in Fos KO MDMs under osteoclastogenic conditions was rescued by retroviral gene transfer of c-Fos but not by that of NFATc1 (Fig. 2C, left panel). As expected, both c-Fos and NFATc1 restored expression of Calcr (encoding calcitonin receptor), a target gene of NFATc1, in Fos KO MDMs (Fig. 2C, right panel). Furthermore, the 1.6-kb fragment containing the ephrinA2 promoter and a promoter containing consensus AP-1-binding sites (5× TRE) were both activated by a tethered AP-1 dimer, c-Fos∼c-Jun in which “∼” indicates a polypeptide linker (16) (Fig. 2D). These results demonstrate that ephrinA2 expression is c-Fos-dependent and NFATc1-independent.

FIGURE 2.

c-Fos-dependent, NFATc1-independent induction of ephrinA2. A, qRT-PCR analysis of ephrinA2 expression. Wild-type (WT) and Fos KO splenocytes and WT bone marrow cells (BM) were cultured in the presence of RANKL for 1-3 days. **, p < 0.01 versus WT spleen control. B, sensitivity of ephrinA2 induction to FK506 at various concentrations (μm). qRT-PCR analysis of ephrinA2 and ephrinB2 was 4 days after RANKL treatment. **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle control (-). C, qRT-PCR analysis of RANKL-induced ephrinA2 (day 1) and calcitonin receptor (day 7) in Fos KO MDMs infected with retroviruses expressing empty cassette (emp), c-Fos, or a constitutively active NFATc1 (NFATc1). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus empty cassette. D, reporter assay using RAW264.7 cells transiently transfected with pGL3 luciferase plasmid driven by the 1.6-kb ephrinA2 promoter (eA2) or the multimerized consensus AP-1-binding sites (5× TRE) and an activator plasmid expressing empty (emp), c-Fos or “single chain” c-Fos∼c-Jun. Transfection efficiency was normalized using Renilla luciferase activity. *, p < 0.05 versus empty cassette. Error bars represent means ± S.E. (n = 3).

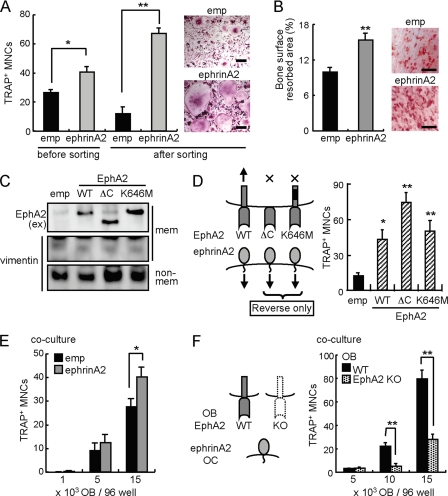

Reverse ephrinA2-expressing retroviral vector. Higher numbers of TRAP-positive MNCs were produced for ephrinA2-infected MDMs than empty vector-infected controls, and the effect was more prominent when infected cells were enriched by cell sorting before inducing differentiation (Fig. 3A). Consistently, ephrinA2-expressing MDMs resorbed a larger area of bone surface compared with controls (Fig. 3B); this reflected enhanced differentiation because the bone resorption activity per cell remained unchanged as judged by re-plating experiments of mature osteoclasts (data not shown). To stimulate reverse signaling through ephrinA2 into osteoclasts in the absence of forward signaling, we transfected a wild-type (WT) and EphA2 mutants lacking the cytoplasmic region (ΔC) or lacking kinase activity of intracellular region (K646M) into MDMs. As expected, these EphA2 proteins were found in a membrane fraction of MDMs (Fig. 3C). The ectodomain of ΔC and K646M enhanced osteoclast differentiation as WT did, suggesting that ephrinA2 induces reverse signaling into osteoclast precursors and positively regulates osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

EphrinA2 reverse signaling enhances osteoclast differentiation. A, overexpression of ephrinA2 in osteoclast precursors. emp, empty retroviral GFP vector. ephrinA2, ephrinA2-expressing GFP retrovirus. Infected cells (before sorting) and sorted GFP-positive cells (after sorting) were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 3 days. The giant (longitudinal length >125 μm) TRAP+ MNCs were counted. Scale bars, 50 μm. B, bone resorption assay. Infected cells as in A were cultured on bovine bone slices in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 10 days. Left panel, values represent bone surface resorbed (%). Right panel, resorption pits (red) are shown. Scale bars, 500 μm. C, immunoblot analysis of EphA2 mutants. MDMs were infected with an empty retrovirus (emp) or viruses expressing EphA2 (WT), EphA2 lacking cytoplasmic region (ΔC), or EphA2 lacking kinase activity (K646M). Membrane (mem) and non-membranous (non-mem) fractions were enriched. EphA2 proteins were detected using anti-EphA2 extracellular domain (ex) antibody. Vimentin was used as a control for non-membranous proteins. D, overexpression of EphA2 mutants in osteoclast precursors. MDMs were infected with empty (emp), EphA2-WT, -ΔC, and -K646M retroviral vectors and were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 4 days. The giant TRAP+ MNCs were counted. E, co-culture of ephrinA2-expressing MDMs with calvarial osteoblasts (OB). MDMs infected with empty (emp) or ephrinA2 retrovirus were seeded at a low cell density (1000 cells/96 wells) together with 1000, 5000, and 15,000 osteoblasts per well. F, osteoclastogenic activity of osteoblasts lacking EphA2. Wild-type MDMs (5000 cells/96 wells) were co-cultured with WT or EphA2-deficient (EphA2 KO) osteoblasts at 5000, 10,000 and 15,000 cells per well. The giant TRAP+ MNCs were counted. Error bars represent means ± S.E. (n = 4-5). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus controls indicated by black bars.

To determine whether osteoblasts could enhance osteoclastogenesis through ephrinA2 on osteoclasts, we co-cultured ephrinA2-expressing MDMs with calvarial osteoblasts (OB). Overexpression of ephrinA2 in osteoclasts significantly increased TRAP-positive MNCs in a manner that depended on osteoblast cell number (Fig. 3E). Consistently, osteoblasts lacking EphA2 were less able to induce osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 3F). Reduction in RANKL or increase in the decoy receptor osteoprotegerin could explain the reduced osteoclast-inductive activity, and a ratio of RANKL/osteoprotegerin was decreased in osteoblasts lacking EphA2 than WT osteoblasts by qRT-PCR (data not shown). However, RANKL addition into co-culture medium did not relieve suppressed osteoclast-inductive activity of osteoblasts lacking EphA2. These data suggest that osteoclast differentiation is enhanced through ephrinA2 reverse signaling.

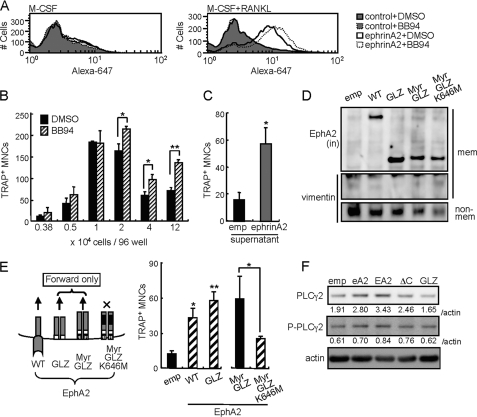

Forward Signaling through EphA2 Also Enhances Osteoclastogenesis—It is known that ephrinA2 is cleaved in trans by membrane MMPs, especially a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) 10 (21, 22). Cells in the osteoclast lineage express ADAM10 and other ADAMs during differentiation (data not shown) (23, 24). To determine whether MMPs cleave ephrinA2 on osteoclasts, we used fluorescence-activated cell sorter to analyze cell surface ephrinA2 in the presence or absence of BB94, a widely used inhibitor of MMPs and ADAMs. The amount of RANKL-induced ephrinA2 measured as mean fluorescence intensity was moderately but significantly increased by BB94 treatment (Fig. 4A, right panel; p = 0.005). EphrinA2 was not detected on MDMs treated with M-CSF alone (Fig. 4A, left panel). These data indicate that MMPs cleave a fraction of cell surface ephrinA2 on osteoclast precursors. Next we determined the effect of BB94 on osteoclast differentiation. The number of giant osteoclasts was slightly but significantly increased by BB94 treatment when cells were seeded at high cell densities (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that osteoclast surface proteins such as ephrinA2, which are cleaved by MMPs in the absence of BB94, enhance osteoclastogenesis in a cell-cell contact-dependent manner. To examine potential functions of released ephrinA2 after cleavage, osteoclastogenesis was induced in the presence of the culture supernatants of MDMs overexpressing ephrinA2 (Fig. 4C). The supernatant enhanced formation of giant osteoclasts, suggesting that soluble ephrinA2 stimulates EphAs on osteoclast precursors and enhances osteoclast differentiation via forward signaling. We therefore determined the effect of forward signaling through EphA2 in the absence of reverse signaling. We infected MDMs with retroviruses expressing wild-type EphA2, two constitutively active forms of the EphA2 cytoplasmic region (GLZ, the GCN4 leucine zipper was added to the amino terminus of the EphA2 cytoplasmic region; and Myr-GLZ, a myristoylation sequence was added to the amino terminus of GLZ), and a kinase-dead mutant of Myr-GLZ (Myr-GLZ-K646M) (19) (Fig. 4D). We found that overexpression of GLZ and Myr-GLZ but not Myr-GLZ-K646M enhanced giant osteoclast formation as efficiently as wild-type EphA2 (Fig. 4E). These data demonstrate that EphA2 positively regulates osteoclastogenesis through forward signaling. Collectively, both reverse and forward signaling of ephrinA2-EphA2 interaction result in enhanced osteoclastogenesis. It is known that both glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins and EphA4 signaling can activate phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) (27, 28). Furthermore, PLCγ2 positively regulates osteoclastogenesis (29-31). To determine whether ephrinA2 or EphA2 on osteoclasts regulates PLCγ2, we analyzed expression of PLCγ2 and phosphorylated PLCγ2 in MDMs expressing ephrinA2, EphA2, EphA2-ΔC (to stimulate reverse signaling through ephrinA2), and EphA2-GLZ (to activate forward signaling through EphA2) using immunoblot analysis. 48 h after RANKL addition, PLCγ2 and phosphorylated PLCγ2 expression were increased in ephrinA2-, EphA2-, and EphA2-ΔC-expressing cells but not in GLZ-expressing cells (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that ephrinA2 reverse signaling up-regulates PLCγ2 expression.

FIGURE 4.

EphA2 forward signaling also enhances osteoclast differentiation. A, fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of ephrinA2 on MDMs after 42 h of treatment with either vehicle (DMSO) or MMP inhibitor BB94 in the presence of M-CSF alone (left panel) or M-CSF and RANKL (right panel). control, secondary antibody (Alexa-647) alone. ephrinA2, anti-ephrinA2 and secondary antibodies. B, giant TRAP+ MNCs were counted in cultures of MDMs seeded at various densities and treated with DMSO or BB94 in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 4 days. C, effect of conditioned medium of ephrinA2-overexpressing MDMs on osteoclastogenesis. Conditioned medium was prepared by culturing MDMs infected with empty (emp) or ephrinA2 retroviruses for 3 days in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL. Freshly isolated MDMs were cultured in the conditioned medium, and giant TRAP+ MNCs were counted on day 4. D, immunoblot analysis of EphA2 mutants. MDMs were infected with retroviral vectors expressing EphA2 (WT), constitutively active forms of EphA2 lacking the ectodomain (GLZ and Myr-GLZ), or a kinase dead Myr-GLZ (Myr-GLZ-K646M). Membrane (mem) and non-membranous (non-mem) fractions were enriched. EphA2 proteins were detected using anti-EphA2 intracellular (in) domain antibody. Vimentin was used as a control of non-membranous proteins. E, overexpression of EphA2 mutants in osteoclast precursors. MDMs were infected with empty (emp), EphA2-WT, -GLZ, -Myr-GLZ, and -Myr-GLZ-K646M retroviral vectors and were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 4 days. The giant TRAP+ MNCs were counted. F, immunoblot analysis of PLCγ2 and phosphorylated PLCγ2(P-PLCγ2). MDMs were infected with empty (emp), ephrinA2 (eA2), EphA2-WT (EA2), -ΔC, or -GLZ retroviral vectors and were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 2 days. The values indicate intensities of PLCγ2 and P-PLCγ2 bands normalized to actin (relative index). Error bars represent means ± S.E. (n = 3-4). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus controls shown in black bars.

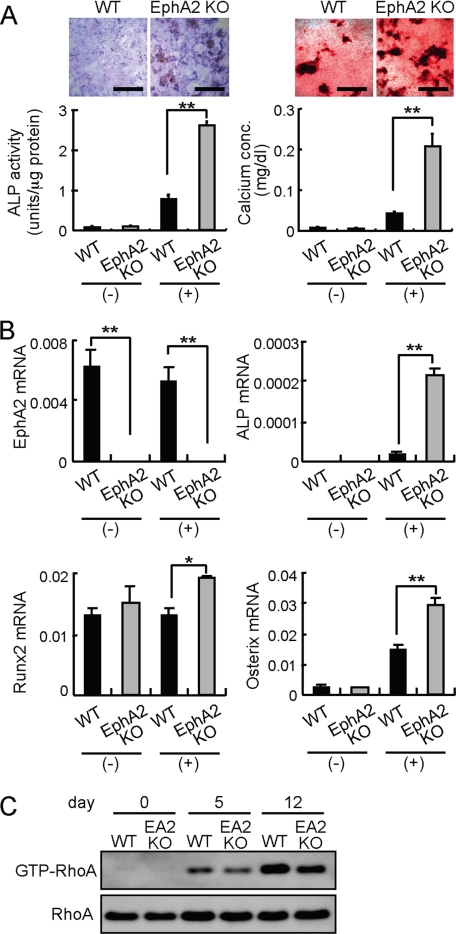

EphA2 Signaling Suppresses Osteoblast Differentiation—Next, we hypothesized that RANKL-induced ephrinA2 on osteoclast precursors could act on osteoblasts by stimulating EphA2 on osteoblasts. To determine the function of EphA2 on osteoblasts, calvarial osteoblasts were isolated from EphA2-deficient newborn mice and were cultured under osteoblastogenic conditions. Staining for ALP activity and calcium deposition revealed that osteoblasts lacking EphA2 differentiate more efficiently than wild-type controls (Fig. 5A). As expected, expression of EphA2 was undetectable in EphA2 KO osteoblasts (Fig. 5B). Expression levels of osteoblast differentiation markers, ALP, Runx2 and Osterix, were increased in EphA2-deficient osteoblasts compared with wild-type osteoblasts (Fig. 5B). We have previously shown that GTP-RhoA negatively regulates osteoblastogenesis in mice (11). In osteoblasts lacking EphA2, we found that enhanced osteoblastogenesis is accompanied by a decrease in GTP-RhoA, suggesting that signaling through EphA2 into osteoblasts suppresses osteoblast differentiation by activating RhoA (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

EphA2 signaling inhibits osteoblast differentiation. A, differentiation of wild-type (WT) and EphA2-deficient (EphA2 KO) calvarial osteoblasts. Osteoblast precursors were cultured in the absence (-) or presence (+) of ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate. ALP staining (upper left panels) and calcium staining (upper right panels) were performed after 6 and 13 days, respectively. Scale bars, 500 μm. ALP activities and calcium concentrations were quantified. B, qRT-PCR analysis of osteoblast markers in WT and EphA2 KO calvarial osteoblasts cultured under non-osteoblastogenic (-) or osteoblastogenic (+) conditions. RNAs were prepared on day 8. Error bars represent means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus controls shown in black bars. C, RhoA activities in differentiating osteoblasts lacking EphA2. day, after addition of ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate.

DISCUSSION

Accumulating evidence indicates that ephrins and Ephs influence cell proliferation and fate determination (25). In this study, we found that interaction between osteoclastic ephrinA2 and either osteoclastic or osteoblastic EphA2 regulates differentiation of these cell types in a different way from ephrinB2-EphB4 interaction.

Our data revealed that ephrinA2 mRNA was rapidly induced after RANKL addition following c-Fos induction, with expression peaking by 24 h. This early induction of ephrinA2 during osteoclast differentiation is c-Fos-dependent but NFATc1-independent. Because ephrinB2 is expressed at a later stage of osteoclast differentiation and the induction is dependent on both c-Fos and NFATc1 (11), the c-Fos-NFATc1 transcriptional cascade differentially regulates expression of ephrinA2 and ephrinB2. Luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that the 1.6-kb upstream region of ephrinA2 gene was activated by c-Fos∼c-Jun. Although there are a few potential c-Fos/AP-1-binding sites in this region, it is not known whether that c-Fos directly binds to the ephrinA2 or not. Further analysis is necessary to identify binding sites of c-Fos/AP-1 in the ephrinA2 promoter during osteoclastogenesis.

EphA2 and EphA4 are both potential receptors for ephrinA2. Although EphA4 is expressed in mature osteoclasts, EphA2 is expressed in osteoclast precursors even before RANKL addition. Therefore, EphA2 is likely the receptor for ephrinA2 when interaction occurs among osteoclast precursors during early differentiation. Once differentiated, EphA4 on mature osteoclasts probably participates in interaction with ephrinA2. Curiously, qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression levels of ephrinA2 and EphA2 during osteoclast differentiation are reciprocal in that EphA2 expression is reduced when ephrinA2 is increased. This is apparently unfavorable for interaction between synchronously differentiating osteoclasts. EphrinA2-EphA2 interaction may occur more preferably between osteoclasts at different stages of differentiation, i.e. between early precursors and mature osteoclasts, so that differentiation of early precursors is accelerated to contribute to cell-cell fusion and functional activation. We indeed found that ephrinA2 reverse signaling and EphA2 forward signaling both enhance osteoclast differentiation. This is in contrast to the role of ephrinAs and EphAs in motor neurons, where they exert opposing effects on neuronal growth cone behavior (26).

Our data revealed that ephrinA2 reverse signaling into osteoclasts up-regulated expression of PLCγ2 as well as phosphorylated PLCγ2. It is plausible that ephrinA2 signaling modulates intracellular calcium signaling and NFATc1 activation through PLCγ2. Whether ephrinA2 signaling influences intracellular calcium oscillation should be examined in the future (32). Signaling through EphA2 on osteoblasts inhibits osteoblast differentiation based on the observation that EphA2-deficient calvarial osteoblasts differentiate more efficiently than wild-type controls. At present, it is unclear whether the observed suppression is because of the reverse signaling via ephrinA or to the forward signaling via EphA2 into osteoblasts. Our data suggest that suppression of osteoblast differentiation by ephrinA2-EphA2 is mediated by increased RhoA activity.

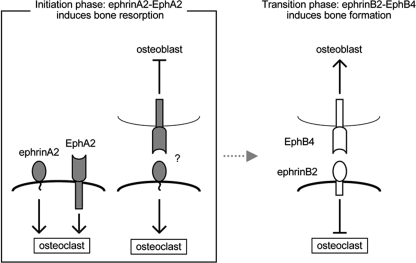

We propose that the osteoclast precursor senses its neighboring osteoclast precursors as well as osteoblasts through ephrinA2-EphA2 interactions. Osteoclast precursors mutually enhance differentiation toward cell-cell fusion, and ephrinA2 reverse signaling into osteoclasts may also be stimulated by EphA-expressing osteoblasts. In summary, at the initiation phase of bone remodeling, ephrinA2-EphA2 interaction promotes bone resorption and concomitantly suppresses osteoblastogenesis (Fig. 6). This is in contrast to the transition phase of bone remodeling from bone resorption to bone formation, when ephrinB2-EphB4 interaction inhibits osteoclastogenesis with concomitant promotion of bone formation (Fig. 6). We conclude that bone remodeling is distinctly regulated by ephrin-Eph of both classes A and B.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic presentation of ephrin-Eph interactions during bone remodeling. At the initiation phase of bone remodeling, ephrinA2-EphA2 interaction enhances osteoclastogenesis and inhibits osteoblastogenesis. At the transition phase, ephrinB2-EphB4 interaction inhibits osteoclastogenesis and enhances osteoblastogenesis (11). Note that the effects of ephrin-Eph on osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation are opposite between classes A and B.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate T. Hunter, M. Tanaka, and R. Sakai for EphA2 mutant plasmids; S. Fukuse, M. Jinno, Y. Sasaki and Y. Kato for technical support; S. Suzuki for cell sorting; and J. Takatoh, T. Miyamoto, S. Mochizuki, C. Zhao, T. Oikawa, H. Tabata, and K. Nakajima for critical suggestions.

This work was supported by Grant-in-aid for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellows 20-5884, by a Keio University grant-in-aid for Encouragement of Young Medical Scientists, The 21st Century COE Program at Keio University, and by Medical School Faculty and Alumni Grants of the Keio University Medical Science Fund, Tokyo.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MNC, multinucleated cell; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; MDM, M-CSF-dependent macrophage; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; M-CSF, macrophage-colony-stimulating factor; OPG, osteoprotegerin; PLC, phospholipase C; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; TRE, TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate)-response element; GFP, green fluorescent protein; OB, osteoblast; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RT, reverse transcription; qRT, quantitative RT; KO, knock-out; WT, wild type; ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase.

References

- 1.Karsenty, G., and Wagner, E. F. (2002) Dev. Cell 2 389-406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitelbaum, S. L., and Ross, F. P. (2003) Nat. Rev. Genet 4 638-649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuo, K., and Irie, N. (2008) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 473 201-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grigoriadis, A. E., Wang, Z. Q., Cecchini, M. G., Hofstetter, W., Felix, R., Fleisch, H. A., and Wagner, E. F. (1994) Science 266 443-448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takayanagi, H., Kim, S., Koga, T., Nishina, H., Isshiki, M., Yoshida, H., Saiura, A., Isobe, M., Yokochi, T., Inoue, J., Wagner, E. F., Mak, T. W., Kodama, T., and Taniguchi, T. (2002) Dev. Cell 3 889-901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishida, N., Hayashi, K., Hoshijima, M., Ogawa, T., Koga, S., Miyatake, Y., Kumegawa, M., Kimura, T., and Takeya, T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 41147-41156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asagiri, M., Sato, K., Usami, T., Ochi, S., Nishina, H., Yoshida, H., Morita, I., Wagner, E. F., Mak, T. W., Serfling, E., and Takayanagi, H. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 202 1261-1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuo, K., Galson, D. L., Zhao, C., Peng, L., Laplace, C., Wang, K. Z., Bachler, M. A., Amano, H., Aburatani, H., Ishikawa, H., and Wagner, E. F. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 26475-26480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arvanitis, D., and Davy, A. (2008) Genes Dev. 22 416-429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasquale, E. B. (2008) Cell 133 38-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao, C., Irie, N., Takada, Y., Shimoda, K., Miyamoto, T., Nishiwaki, T., Suda, T., and Matsuo, K. (2006) Cell Metab. 4 111-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allan, E. H., Hausler, K. D., Wei, T., Gooi, J. H., Quinn, J. M., Crimeen-Irwin, B., Pompolo, S., Sims, N. A., Gillespie, M. T., Onyia, J. E., and Martin, T. J. (2008) J. Bone Miner. Res. 23 1170-1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda, C., Kubota, S., Kawata, K., Aoyama, E., Sumiyoshi, K., Oka, M., Inoue, M., Minagi, S., and Takigawa, M. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374 22-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naruse-Nakajima, C., Asano, M., and Iwakura, Y. (2001) Mech. Dev. 102 95-105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishiwaki, T., Yamaguchi, T., Zhao, C., Amano, H., Hankenson, K. D., Bornstein, P., Toyama, Y., and Matsuo, K. (2006) J. Bone Miner. Res. 21 596-604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakiri, L., Takada, Y., Radolf, M., Eferl, R., Yaniv, M., Wagner, E. F., and Matsuo, K. (2007) Bone (NY) 40 867-875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morita, S., Kojima, T., and Kitamura, T. (2000) Gene Ther. 7 1063-1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka, M., Kamata, R., and Sakai, R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 42375-42382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter, N., Nakamoto, T., Hirai, H., and Hunter, T. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4 565-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selander, K., Lehenkari, P., and Vaananen, H. K. (1994) Calcif. Tissue Int. 55 368-375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hattori, M., Osterfield, M., and Flanagan, J. G. (2000) Science 289 1360-1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janes, P. W., Saha, N., Barton, W. A., Kolev, M. V., Wimmer-Kleikamp, S. H., Nievergall, E., Blobel, C. P., Himanen, J. P., Lackmann, M., and Nikolov, D. B. (2005) Cell 123 291-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verrier, S., Hogan, A., McKie, N., and Horton, M. (2004) Bone (NY) 35 34-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi, S. J., Han, J. H., and Roodman, G. D. (2001) J. Bone Miner. Res. 16 814-822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmberg, J., Armulik, A., Senti, K. A., Edoff, K., Spalding, K., Momma, S., Cassidy, R., Flanagan, J. G., and Frisen, J. (2005) Genes Dev. 19 462-471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marquardt, T., Shirasaki, R., Ghosh, S., Andrews, S. E., Carter, N., Hunter, T., and Pfaff, S. L. (2005) Cell 121 127-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki, K. G., Fujiwara, T. K., Edidin, M., and Kusumi, A. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177 731-742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou, L., Martinez, S. J., Haber, M., Jones, E. V., Bouvier, D., Doucet, G., Corera, A. T., Fon, E. A., Zisch, A. H., and Murai, K. K. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 5127-5138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen, Y., Wang, X., Di, L., Fu, G., Chen, Y., Bai, L., Liu, J., Feng, X., McDonald, J. M., Michalek, S., He, Y., Yu, M., Fu, Y. X., Wen, R., Wu, H., and Wang, D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 29593-29601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mao, D., Epple, H., Uthgenannt, B., Novack, D. V., and Faccio, R. (2006) J. Clin. Investig. 116 2869-2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura, I., Lipfert, L., Rodan, G. A., and Le, T. D. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152 361-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuroda, Y., Hisatsune, C., Nakamura, T., Matsuo, K., and Mikoshiba, K. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 8643-8648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.