Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to examine relations among multiple child and family protective factors, neighborhood disadvantage, and positive social adjustment in a sample of 226 urban, low SES boys followed from infancy to early adolescence. The results indicated that child IQ, nurturant parenting, and parent–child relationship quality, measured in early childhood, were all significantly associated with a composite measure tapping low levels of antisocial behavior and high levels of social skills at ages 11 and 12. Parental romantic partner relationship quality (RPRQ) was only significantly related to positive social adjustment in the context of low levels of neighborhood disadvantage. Results suggest that with the exception of RPRQ, these protective factors operate in a comparable manner with respect to positive social adjustment for this predominantly low-income urban sample of boys.

Keywords: Resilience, Neighborhood disadvantage, Protective factors, Low-income families

Introduction

The study of resilience provides information on conditions under which established risk factors are not associated with negative outcomes (Masten 2001). In combination with research on vulnerability, such research can help to inform theories of psychopathology and to guide public policy and intervention efforts to improve the lives of children at risk for maladaptive outcomes (Masten 2001). Broadly defined, resilience refers to the process through which positive outcomes are achieved in the context of adversity (Masten 2001). Although many studies on resilience have identified certain factors that may be protective in the context of risk, challenging issues remain regarding the conceptualization of resilience, including: (1) establishing “high risk” environments; (2) defining positive outcome; and (3) understanding the process of resilience across levels of varying risk. In addition, there are relatively few longitudinal studies of resilience that focus on protective factors in early childhood, as they relate to later outcomes (see Werner and Smith 1992, for a notable exception). This paper seeks to address these issues to advance our conceptual and empirical understanding of resilience, particularly in the context of chronic risk. To this end, relations were examined among multiple child and family protective factors and positive social adjustment in a sample of urban, low SES boys followed from infancy to early adolescence. Furthermore, to elucidate the process of resilience across levels of risk, we examined the relations between protective factors and positive social adjustment differed depending on the severity and chronicity of neighborhood risk.

What is “High Risk”?

Although resilience requires risk, there have been relatively few studies of resiliency conducted on children living in poverty, arguably the one of the most prevalent and pervasive risk factor (Gorman-Smith et al. 1999); instead many studies have utilized European American, middle-class samples (e.g., Criss et al. 2002; Masten et al. 1999), or have studied normative birth cohorts (e.g., Werner and Smith 1992). The inner-city poor contend with a substantial number of stressors and adversities, including community violence, crowding, poor quality schools, and inadequate housing (McLoyd 1998). Importantly, although poverty is typically conceptualized as a dichotomous and static variable, children living in extreme or chronic poverty tend to have worse outcomes than children exposed to less severe or intermittent poverty (Duncan et al. 1994).

Low income by itself, however, does not always accurately represent environmental conditions because housing and financial support may actually be adequate due to other sources of support, such as extended family (Campbell et al. 2000). For example, a single mother may have a very small personal income, but if she lives with her parents and receives the benefits associated with their income she may not experience many of the hardships typically associated with low income (e.g., living in a dangerous environment, decreased access to resources). Conversely, living in a poor, dangerous neighborhood virtually guarantees exposure to risk factors outside the home that affect child development (Campbell et al. 2000). Although neighborhood disadvantage can be confounded with demographic and family risk, studies that have accounted for such factors have shown that neighborhood quality contributes independent variance in relation to child outcomes after accounting for these socioeconomic and family factors (see Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2003, for a review). Thus, neighborhood disadvantage provides a strong measure of environmental risk.

Positive Outcome

In addition to establishing the presence of risk, researchers must determine that the child demonstrates a “good” or “positive” outcome (Masten 2001). Whether a good outcome is operationalized as merely the absence of a negative outcome (e.g., psychopathology), the presence of positive adjustment (e.g., academic or social competence), or the combination of both, is a matter of controversy and depends upon the risk factor in question and the researcher's theoretical orientation. However, resilience is not an “all-or-nothing” phenomenon; in fact studies demonstrate that resilience is often inconsistent across domains (e.g., Radke-Yarrow and Brown 1993; Werner and Smith 1992). For example, in a study of inner city adolescents, Luthar (1991) found that youths who were “resilient” in terms of social competence exhibited high rates of internal distress. For this reason, Luthar and Zelazo (2003) recommend measuring competence across domains to ensure a broader and more accurate portrait of functioning.

Protective Factors

Protective factors are defined as characteristics of the child, family, and wider environment that reduce the negative effect of adversity on child outcome (Masten and Reed 2002). A number of factors, including child IQ, emotion regulation, parenting, low parental discord, advantaged SES, effective schools, and safe neighborhoods, are associated with positive outcomes in the context of high risk (Masten and Reed 2002). However, much of this research is based on evaluating protective factors beginning in middle childhood or only following children through the school-age period (e.g., Luthar 1991; Stouthamer-Loeber et al. 2002). Research from intervention studies indicates that both child problem behavior and parent management strategies are more amenable to intervention during early versus later childhood (Olds 2002; Webster-Stratton and Taylor 2001). Thus, to augment our knowledge on resilience there is still a need for longitudinal research on the effects of protective factors in early childhood on subsequent functioning during adolescence and beyond (Yates et al. 2003).

Furthermore, there is some evidence that factors that are protective in lower risk contexts may not be as powerful in contexts of extreme risk. In fact, several studies have found that some protective factors are diminished in the context of severe neighborhood disadvantage (Silk et al. 2007; Stouthamer-Loeber et al. 2002), with differences emerging between low income urban neighborhoods and inner city neighborhoods or projects (Gorman-Smith et al. 1999; Shaw et al. 2004). Thus it is important to determine whether protective factors work similarly across levels of neighborhood disadvantage, or whether the benefits are limited to specific contexts.

Child Characteristics

Child IQ

IQ is one of the most widely researched and validated protective factors in the child domain (Masten and Coatsworth 1998). Children with high IQs may be more likely to possess effective information-processing and problem-solving skills, which enable them to contend with the stresses and challenges they encounter. Children with higher intellectual skills should also perform better at school; increased academic success is associated with the adoption of social norms and integration into prosocial peer groups (Masten and Coatsworth 1998). Across risk status, child IQ has consistently been found to predict a range of positive outcomes, including academic achievement, pro-social behavior, and peer social competence (Masten et al. 1999), as well as the absence of antisocial behavior (White et al. 1989).

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation has been studied less frequently as a protective factor than IQ, but there is ample research to suggest that it is an important component of successful adaptation (Masten and Coatsworth 1998). Emotion regulation has been referred to as processes that monitor, evaluate, and/or modify the intensity and duration of emotional reactions to accomplish one's goals (Eisenberg et al. 1997). Children who are adept at managing their emotions may be better able to proactively cope with stressors, and thereby decrease the associated negative effects. Across contexts of risk, such children should function better in school and social relationships because they are able to modulate negativity and emotional expression. Conversely, a lack of control over emotion has been consistently associated with problem behaviors in children (Calkins and Fox 2002), while the ability to manage one's emotional expression has predicted more positive social functioning in middle childhood both contemporaneously and longitudinally (Eisenberg et al. 1997).

Family Characteristics

Parenting Strategies

A wide variety of specific parenting practices have been shown to be associated with children's positive social adjustment, including warmth, consistent discipline, responsiveness, structure, and monitoring (Masten and Reed 2002). One of the factors most consistently associated with positive outcomes is nurturant, responsive parenting. Across risk status, various aspects of nurturant or responsive parenting have been associated with lower levels of externalizing and internalizing behavior (Masten et al. 1999; Werner and Smith 1992), as well as higher levels of peer social competence (Wyman et al. 1999).

Parent–Child Relationship Quality

In addition to specific parenting practices, the quality of the parent–child relationship has also been examined in relation to positive child outcomes. Theoretically, having a good relationship with a parent prepares the child to engage in healthy productive relationships with other people in the social environment. In support of this idea, Ingoldsby et al. (2001) found that having a good relationship with at least one parent was associated with less conflictual relationships with siblings, teachers, and peers. Researchers have found that the quality and closeness of the parent–child relationship relates to child outcomes across risk status (Emery and Forehand 1996; Radke-Yarrow and Brown 1993). Several studies, however, have found that qualities of the parent–child relationship are not related to positive outcomes for children living in the worst neighborhoods (Gorman-Smith et al. 1999; Shaw et al. 2004).

Marital Quality

Much research has focused on how the quality of the marriage may affect parenting and the parent–child relationship, for example, by increasing the parent's psychosocial resources and ability to consistently deal with child behavior (e.g., Belsky et al. 1991). Direct associations between marital quality and various child outcomes also have been demonstrated (Cummings et al. 2004). For example, a positive marital relationship may increase children's emotional security, which in turn can affect their ability to cope with daily stressors (Davies and Cummings 1994). Conversely, marital relationships characterized by low conflict or the use of constructive tactics to resolve conflict have been associated with low levels of child adjustment problems (Belsky et al. 1991; Cummings et al. 2004). Marital quality also has been positively associated with a range of positive child outcomes (Belsky 1996; Porter et al. 2003). Indeed, low discord between parents may serve as a key protective factor (Emery and Forehand 1996).

Study Aims

The current study addresses several issues pertinent to the literature on resilience. First, in contrast to studies that have relied on cross-sectional methodologies investigating predominantly European American, middle-class samples (e.g., Criss et al. 2002), the present study consists of a sample of low-income, ethnically diverse boys followed prospectively from age 1.5 to early adolescence. Importantly, the entire sample could be considered high risk, relative to other samples, due to low socio-economic status. Second, we also investigated whether the relative benefits of certain protective factors might differ depending on both the severity and persistence over time of neighborhood disadvantage, which provides a strong measure of environmental risk. The question of whether protective processes differ across levels of risk is an important one for designing effective intervention programs, and can also contribute to our theoretical conceptualization of resilience at severe levels of risk.

Third, the current study takes a person-centered approach to defining resilience, which enables us to examine whether protective factors differentiate between groups of children. Furthermore, resilience was defined both by low levels of antisocial behavior and high levels of social skills to ensure that children were functioning adaptively across domains. Finally, this study responds to calls for examining multiple aspects of risk, protective factors, and positive adjustment (Masten et al. 1999), as well as to evaluate the contribution of protective factors in early childhood on subsequent functioning (Yates et al. 2003). Protective factors in early childhood are of particular interest, given that interventions may be more effective when initiated in early versus later childhood (e.g., Olds 2002).

The current study had two aims: (1) to examine protective factors during early childhood as predictors of positive social adjustment (low antisocial behavior and high social skills) in early adolescence among low income boys; and (2) to examine the moderating role of neighborhood disadvantage in the association between protective factors and positive social adjustment. Family contextual adversity was defined by neighborhood disadvantage measured longitudinally from age 1.5- to 10 years-old, and resilient adaptation was defined by low levels of externalizing problems and high levels of social skills as rated by multiple informants. It was hypothesized that specific early child and family characteristics, including child IQ, emotion regulation skills, nurturant parenting, the quality of the parent–child relationship, and parental romantic partner relationship quality (RPRQ) would be associated with low antisocial behavior and high social skills in early adolescence. However, in line with other research comparing protective factors at different levels of high neighborhood risk (e.g., Gorman-Smith et al. 1999; Shaw etal. 2004), we expected that within this predominantly low-income sample the child and family factors would be more important at low and moderate levels of neighborhood disadvantage than at the highest levels of disadvantage.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were part of the Pitt Mother and Child Project (PMCP), a longitudinal study of child vulnerability and resiliency in low-income families. In 1991 and 1992, 310 infant boys and their mothers were recruited from Allegheny County Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) Nutrition Supplement Clinics when the boys were between 6 and 17 months old. The sample was restricted to boys to increase the likelihood of emergent conduct problems and more serious forms of antisocial behavior during adolescence. At the time of recruitment, 53% of the target children in the sample were European American, 36% were African American, 5% were biracial, and 6% were of other races (e.g., Hispanic American or Asian American). Two-thirds of mothers in the sample had 12 years of education or less. The mean per capita income was $241 per month ($2,892 per year), and the mean Hollingshead SES score was 24.5, indicative of a working class sample. Thus, a large proportion of the families in this study could be considered high risk due to their low socioeconomic status. The current study utilized a subsample of 226 boys who had data on both later antisocial behavior and social skills.

Retention rates have generally been high at each of ten timepoints from age 1.5- to 12-years old, with 90−94% of the initial 310 participants completing visits at ages 5 and 6. Some data are available on 89% or 275 participants at ages 10, 11, or 12. When compared with those who dropped out at earlier times, participants who remained in the study at ages 11 and 12 showed no difference on the CBCL Externalizing factor at ages 2, 3.5 or 5 (all p values >0.05). In fact, similar comparisons using the narrow-band CBCL Aggression factor show that retained participants had significantly higher scores at ages 2 (F=7.42, p<0.01) and 3.5 (F=7.42, p< 0.01) than those participants who no longer participated at ages 11 or 12. Furthermore, scores on these factors did not differ for the 226 participants who had outcome data available on both adolescent social skills and antisocial behavior and those who did not (all p values >0.05). These results suggest that children of families who dropped out of the study were not more likely to exhibit conduct problems than children of families who had outcome data at ages 11 and 12.

Procedures

Target children and their mothers were seen in the home and/or the lab for 2- to 3-h visits at ages 1.5, 2, 3.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 12 years old. During these visits, mothers completed questionnaires regarding socio-demographic characteristics, family issues (e.g., parenting, family members’ relationship quality, maternal well being), and child behavior. Children were interviewed regarding their own adjustment starting at age 5.5. Beginning at age 6 and continuing through age 12, children's teachers were asked to complete several questionnaires on the child's adjustment, including the Social Skills Rating System. The visits with the child and mother at ages 1.5, 3.5, 5, and 11 were conducted in the lab, and the age 2 assessment was a joint home/lab visit; all other visits were conducted in the participants’ homes. Participants were reimbursed for their time at the end of each visit.

Measures

To form more generalizable constructs, efforts were made to aggregate across time and/or informants whenever possible (Patterson et al. 1992). In cases in which data for a composited measure were missing at one of two timepoints or for one of two informants, data from the one data point were used to minimize missing data. When data were missing for a variable, we took a conservative approach and did not impute data, using a list-wise method of deletion to ensure that only subjects with complete data were entered into the analysis.

Risk Factors

Neighborhood Disadvantage

Neighborhood disadvantage was ascertained using data from early to middle childhood (i.e., ages 1.5, 2, 3.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 8, and 10 years old) by geocoding addresses according to US census data at the block group level. Block group is the smallest unit for which all census data are available, and thus provides the best representation of the proximal neighborhood context a child is exposed to. Addresses were collected from 1991 to 2003, so both 1990 and 2000 census data were used. For data from assessments collected between 1990 and 1995, the 1990 census data were used; for data from assessments collected between 1996 and 2003, the 2000 census data were used. Based on methods devised by Wikström and Loeber (2000) and adapted by Winslow (2001), a composite variable of neighborhood disadvantage was generated using the following census block group level variables: (1) median family income, (2) percent families below poverty level, (3) percent households on public assistance, (4) percent unemployed, (5) percent single-mother households, (6) percent African American, (7) percent Bachelor degree and higher. Wikström and Loeber (2000) selected these variables based on previous research investigating neighborhood census structural characteristics associated with antisocial behavior. Support was found for combining these items via factor analysis (see Wikström and Loeber 2000). In the present study, these individual variables were standardized, summed, and then averaged (after reverse scoring median family income and percent Bachelor's degree) to create an overall neighborhood disadvantage score for each block group.

In the current study, risk status was determined by both the severity and persistence over time of neighborhood disadvantage using groups identified based on Nagin's (2005) semiparametric, group-based approach for analyzing trajectories (TRAJ). This method identifies the number of trajectories within a given population and then estimates the proportion of individuals following each trajectory. Consequently, children can be assigned to groups based on their exposure to persistent high or low versus ascending or descending neighborhood disadvantage from age 1.5 to 10. This method allowed for a person-centered approach to risk classification, with an objective, dynamic representation of risk and change over time, rather than collapsing across data points and potentially obscuring important developmental patterns.

Protective Factors

Our overarching goal was to evaluate the predictive validity of protective factors in early childhood; however, we also wanted to select developmentally salient timepoints for optimal assessment, utilizing observable measures when possible. Consequently, some protective factors were measured later than others. For example, as IQ is more reliably assessed in the preschool versus toddler period (Flanagan and Alfonso 1995), it was not assessed until children were 5.5 years old. Alternatively, because emotion regulation and parenting can be reliably assessed as early as the toddler period, both were measured earlier in development. When repeated measures of a variable were available, we used composites of to create a more generalizable construct.

Child IQ

Child IQ was first measured at age 5.5, using a four-subtest short form of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised (WPPSI-R, Wechsler 1989), a commonly used measure of children's cognitive abilities. The Block Design, Geometric Design, Information, and Vocabulary subtests were selected because of the magnitude of their individual factor loadings, split-half reliability coefficients (BD: r=0.85; GD: r=0.79; I: r=0.84; V: r=0.84), and the high reliability and validity coefficients of this set of subtests (0.92 and 0.91, respectively; Sattler 1990). Full Scale IQ (FSIQ) scores were derived according to prorating procedures described by Tellegen and Briggs (1967, cited in Sattler 1990).

Emotion Regulation

During the age 3.5 visit, mothers and sons engaged in a waiting task, in which the child was required to wait for a cookie for 3 min (Marvin 1977). This task was designed to measure children's coping strategies and ability to regulate affect in a delay-of-gratification context. During the 3 min, children had to wait for the cookie with little stimulation to occupy their time. All toys and activities were removed from the room, and the mother was instructed to complete questionnaires. Mothers were also told not to allow the child to have the cookie until the end of the waiting period. At the end of 3 min, the examiner signaled to the mother to give the cookie to the child.

The primary objective in using this measure was to represent child emotion regulation strategies that presumably will be associated with positive outcomes in later childhood, including sustained regulation of negative emotions and the ability to distract oneself. Thus, the following previously coded ratings of strategy and affect were used to generate an emotion regulation variable that focuses on children who show high levels of active distraction and infrequent displays of anger during the waiting task.

Specifically, strategies were coded based on a system created by Grolnick et al. (1996) and adapted by Gilliom et al. (2002). The presence or absence of child active distraction was scored in 10-s intervals. Active distraction was defined as purposeful behaviors in which the focus of attention was shifted from the delay object or task, including fantasy play, exploration of the room, singing, talking with mother, or turning lights on and off. At age 3.5, percent agreement with a master coder was 92.5% and kappa was 0.72. Displays of child anger were also coded from videotape using procedures adapted by Cole et al. (1994) that identify basic emotions through facial action and vocal quality cues. Intensity of anger was rated in seconds on a scale of 0−3, with 0 indicating “none,” 1 indicating “mild,” 2 indicating “moderate,” and 3 indicating “high.” The number of seconds that the child demonstrated mild to high anger was summed to arrive at the total amount of time that the child exhibited some form of anger. Agreement with a master coder was 88% and kappa was 0.76. There was no coder membership overlap between the active distraction and affect coding teams. Coders were unaware of the study hypotheses. To generate a composite factor that accounted for both strategy use and regulation of anger, the standardized anger expression score (total time) was subtracted from the standardized active distraction score to generate an emotion regulation variable (r=−0.39, p<0.01).

Nurturant Parenting

Maternal levels of nurturant, responsive parenting were assessed via observation at age 2 using the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME; Caldwell and Bradley 1984). This commonly used measure combines the use of observational ratings and data gathered from an interview with the parent to generate indices of maternal behavior and quality of the home environment. Each item of the HOME is rated as ‘0’ or ‘1’ based on the item's absence or presence, respectively. Two of the six subscales were aggregated in the present study to create a single measure of Nurturant Parenting. The Acceptance subscale is comprised of eight items assessing maternal response to child misbehavior or distress (e.g., “Parent does not shout at child,” “Parent neither slaps nor spanks child during visit”). Two items regarding the family home (i.e., “At least ten books are present and visible,” “Family has a pet”) were omitted from the scale in the current study because they do not reflect parent–child interactions about misbehavior, rendering this a six-item scale. The 11-item Emotional/Verbal Responsivity subscale rates communicative and affective parent–child interactions (e.g., “Parent caresses or kisses child at least once during visit,” “Parent responds verbally to child's verbalizations”). Past research has demonstrated inter-observer agreement of 0.80 and above, as well as internal consistency of subscales in the moderate range (Bradley 1993). To generate a scale of Maternal Nurturance, items from the six-item Acceptance and 11-item Emotional/Responsivity scales were summed. Internal consistency for the Nurturance variable was found to be adequate in the present sample (α=0.74).

Parent–Child Relationship Quality (PCRQ)

Parent–child relationship quality was measured at ages 5 and 6 using the Adult–Child Relationship Scale, an adaptation of the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (Pianta et al. 1995). The original questionnaire, which focused on teacher–child relationship quality, was modified to assess maternal perception of openness and conflict in the relationship with their child. The Openness scale consists of five items (e.g., “This child likes telling me about himself”; “It's easy to be in tune with what this child is feeling”), and the Conflict scale consists of ten items (e.g., “This child and I always seem to be struggling with each other”; “This child feels I am unfair to him”). A composite of these two scales was used to assess parent–child relationship quality (r=−0.45, p<0.001). An average of the openness and conflict scores from ages 5 to 6 was used to create an overall score for each scale; then the conflict score was subtracted from the openness score to obtain the final score for PCRQ. Internal consistency for this scale was 0.69 and 0.70, respectively, at each timepoint.

Romantic Partner Relationship Quality (RPRQ)

Maternal perception of the level of satisfaction in her marital or significant-other relationship was assessed at the age 1.5-, 2-, and 3.5-year-old visits using the short form of the Marital Adjustment Test (MAT; Locke and Wallace 1959). Prior research demonstrates that this measure differentiates between harmonious and disturbed marriages (Hershorn and Rosenbaum 1985; Locke and Wallace 1959) and also predicts child behavior problems (Emery and O'Leary 1982). In situations in which mothers were recently separated, they were asked to report on that period of the past year when they were still living with their partner. In cases where mothers were not married, they were instructed to complete the scale on a romantic relationship, including their live-in boyfriend, girlfriend, or current dating partner (between 44% and 48% of the sample at each timepoint). An average of the scores from the 1.5, 2, and 3.5 year visits was used to create an overall score for each participant, for which moderate to strong correlations were found between all timepoints (r=0.44 to 0.70, all ps<0.001). Internal consistency ranged from 0.77 to 0.80 across all timepoints.

Child Positive Social Adjustment

To generate a measure of child positive social adjustment, measures of both antisocial behavior and social skills in early adolescence (r=−0.29, p<0.001) were combined to ensure that positive social adjustment was not based solely on the absence of disruptive behavior or only the presence of social skills. Thus, children who were below the median on antisocial behavior and above the median on social skills were classified in the positive social adjustment group (N=71, 31.4%). Child report was utilized to assess antisocial behavior at ages 11 and 12 because of the increasing covert nature of antisocial activities during later school-age and early adolescence, and because maternal reports become increasingly unreliable as children near adolescence (Loeber and Schmaling 1985). Due to the relatively high degree of observability of social skills compared to many antisocial activities during this age period, both parent report at age 11 and teacher report at ages 11 and 12 were used to evaluate boys’ social skills (r= 0.26, p<0.01). To be in the final analyses, participants needed to have data on antisocial behavior and social skills.

Adolescent Antisocial Behavior

At ages 11 and 12, children completed an adapted version of the Self-Report of Antisocial Behavior questionnaire (SRA; Elliott et al. 1985), a semi-structured interview assessing the frequency of delinquent behavior, alcohol and drug use, and related offenses. Because the current participants were at the lower end of the age range for this questionnaire (ages 11−17), we utilized an adapted version of the SRA for younger children that omits delinquent acts that were extremely rare for this age group (e.g., strong arm robbery, rape; Loeber et al. 1989). For purposes of the present study, items with low base rates in our sample were also removed (e.g., carried a hidden weapon; set fires), leaving 10 items for the current version (e.g., “Have you hit other students or gotten into a fight with them?” “Have you taken something from a store without paying for it?”). Previous research utilizing the current sample found adequate internal consistency at ages 10 and 11 (α=0.71; Shaw et al. 2004). As we were interested in the frequency of delinquent behavior, rather than in specific types of delinquent behavior, individual items were averaged to generate a total delinquency scale. A composite of the average problem scores at ages 11 and 12 was used in the present analyses. As noted above, when only one score was available, the age-11 or age-12 report was used as the SRA score.

Child Social Skills

Mothers completed the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham and Elliott 1990) at child age 11, and teachers completed the SSRS at child ages 11 and 12. The SSRS is a questionnaire measuring child cooperation, assertiveness, and self-control with peers and adults (e.g., “attends to instructions,” “appropriately tells you when he or she thinks you have treated him or her unfairly,” “controls temper in conflict situations with peers”). The SSRS parent and teacher versions have 4-week test–retest reliability ranging from 0.75 to 0.88, and internal consistencies of 0.87 and 0.94, respectively (Gresham and Elliot 1990). Internal consistency on the SSRS for this sample ranged from 0.89 to 0.93. Additionally, both versions of the SSRS demonstrate adequate content and criterion-related validity (Gresham and Elliot 1990). At age 11, the standardized total social skills scores from mother and teacher reports were averaged and then aggregated with teacher reports at age 12. Once again, when data from only one timepoint or informant was available, data from that existing data point were used.

Results

Prior to presenting results for each of the study's main hypotheses, descriptive statistics and intercorrelations are described for the independent and dependent variables. This is followed by a discussion of the process for selecting trajectories of neighborhood disadvantage. Next, direct associations between child and family protective factors and child positive social adjustment will be examined, followed by an examination of interactions between individual child and family protective factors and neighborhood disadvantage in relation to child positive social adjustment (low antisocial behavior and high social skills).

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Descriptive statistics for all study variables appear in Table 1, and intercorrelations among protective factors appear in Table 2. Neighborhood disadvantage was negatively associated with positive social adjustment (r=−0.22, p<0.01).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for independent and dependent variables

| Number | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | |||

| WPPSI-Ra (short form) | 188 | 93.54 | 12.73 |

| Observed emotion regulation | 189 | 0.01 | 1.55 |

| HOMEb: acceptance and emotional/verbal responsivity | 215 | 13.73 | 2.92 |

| Adult–child relationship scale | 219 | 1.94 | 1.07 |

| Marital adjustment test | 209 | 100.86 | 28.83 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage score | 226 | 0.34 | 0.94 |

| Dependent variables | |||

| Social skills rating system–teacher report | 158 | 36.34 | 9.74 |

| Social skills rating system–mother report | 216 | 51.38 | 10.16 |

| Self-report of antisocial behavior | 226 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Revised

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment

Table 2.

Intercorrelations among child and family protective factors

| Protective factor | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. WPPSI-Ra (short form) | 0.13 | 0.25*** | 0.01 | −0.10 |

| 2. Observed emotion regulation | – | 0.13* | 0.24*** | 0.19** |

| 3. HOMEb | – | 0.28*** | 0.11 | |

| 4. Parent–child relationship scale | – | 0.29**** | ||

| 5. Marital adjustment test | – |

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Revised

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment

Estimated Trajectories of Neighborhood Disadvantage

A semi-parametric mixture model for censored data was used to estimate trajectories of neighborhood disadvantage based on block-group level census information (Nagin 2005). Several decision criteria are employed to determine the best-fitting model: (1) the statistical significance of the trajectory parameter estimates for each group, which determines the appropriate shape of the individual trajectories; (2) the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), which informs the selection of the optimal number of trajectories; and (3) the posterior probability of membership in each group for each individual based on their actual data sequence. Statistical significance of the trajectory parameter estimates provides information on the model fit of each trajectory group, including indices for intercept, linear, quadratic, and cubic models. BIC scores emphasize parsimony, thus they include a penalty for adding additional trajectory groups (taking into account sample size). Finally, posterior probabilities offer another indicator of the precision of model fit by delineating the likelihood that an individual person would be assigned to each estimated trajectory group based on their observed data. The more accurately the trajectory group reflects the individual's observed data, the higher the posterior probability that the individual would be assigned to that particular trajectory. The individual posterior probabilities for each individual within a trajectory group can be averaged to reveal how well that particular trajectory represents the observed data of the individual group members. Generally, a group average posterior probability over 0.70 is considered adequate (Nagin 2005). For a more detailed explanation of the criteria for selecting trajectory groups, see Nagin (2005).

Because data from both the 1990 and 2000 censuses were used to estimate neighborhood disadvantage (1990 census=1990−1995 assessments; 2000 census=1996−2000 assessments), census year was added as a covariate so that the estimated models would more accurately represent the observed data. This controls for the fact that neighborhood conditions may have changed from the 1990 to 2000 censuses, and allows the trajectories to reflect only changes in neighborhood disadvantage that occurred from families moving into another area. Without controlling for census year, the data would reflect an artificial change in neighborhood condition between 1995 and 1996 as a result of switching from the 1990 census to the 2000 census.

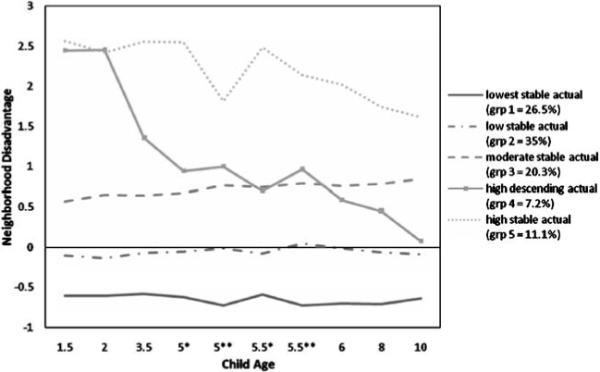

The BIC scores for three, four, five, and six group models were compared. Although the BIC was highest for the six group model, the five group model was ultimately selected, as the six group model split the three lower disadvantage trajectories from the five group model into four low disadvantage trajectories, one of which contained only six participants. Because the primary goal of this study was to compare low disadvantage and high disadvantage neighborhood trajectories, the distinction among these lower disadvantage trajectories was not deemed important. For the five group model, the trajectory coefficients representing linear trends were significant for the two highest disadvantage trajectories (high descending disadvantage group: n=22; chronic high disadvantage group: n=34); thus the other three groups could be represented by an intercept-only trajectory (i.e., the trajectories were flat; lowest disadvantage group: n=81; low disadvantage group: n=107; moderate disadvantage group: n=62). Model selection was corroborated by examining posterior probabilities, which were high, ranging from 0.89 to 0.98 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trajectories of neighborhood disadvantage. *1990 census; **2000 census

Direct Effects of Child and Family Factors

To examine the hypotheses that child and family factors assessed in early childhood would be directly associated with later positive child outcomes, a series of point biserial correlations were computed to assess individual associations between child (i.e., child IQ, emotion regulation) and family (i.e., maternal nurturance, parent–child relationship quality, RPRQ) factors and a dichotomous measure of child positive social adjustment (below median SRA score and above median SSRS score). As expected, child IQ (r=0.17, p<0.05), maternal nurturance (r=0.25, p<0.001), and parent–child relationship quality (r=0.25, p<0.001) were significantly associated with later positive social adjustment, but positive social adjustment was not predicted by early emotion regulation (r=0.09, p>0.05) or RPRQ (r= 0.10, p>0.05). Similar results were found using multiple logistic regression, with maternal nurturance (B=0.18, p< 0.05), and parent–child relationship quality (B=0.45, p< 0.05) remaining significant.

Interactions between Child and Family Factors and Neighborhood Disadvantage

A series of multiple logistic regressions were conducted to examine the hypothesis that neighborhood disadvantage would moderate the relationship between child and family factors and positive social adjustment. Specifically, we expected that child and family factors would be less strongly related to positive social adjustment in the context of more adverse trajectories of neighborhood disadvantage. Independent variables were centered prior to creating the interaction terms. Because neighborhood disadvantage is a categorical variable, each trajectory received a dummy code, with either the chronic disadvantage or the high descending disadvantage group serving as the reference group; hence, two separate regressions were computed for each protective factor. An individual protective factor was entered in the first step, followed by the dummy coded neighborhood trajectories, and finally by the interaction terms between the protective factor and the neighborhood trajectories. When significant interactions were identified, they were examined using the procedure described by Aiken and West (1991) for exploring interactions between continuous and categorical variables, in which the significance of the simple slopes within each level of the categorical groups are tested (e.g., relation between the protective factor and positive outcome is examined within each neighborhood trajectory group).

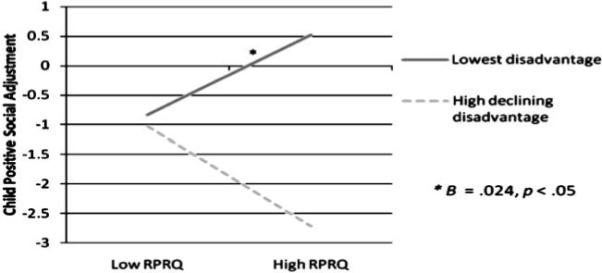

Contrary to study hypotheses, none of the interactions between the child protective factors and neighborhood disadvantage were significant, although several interactions approached significance (Table 3). With high descending risk as the reference group, there was a trend toward interactions between the two child factors and moderate risk (IQ: B=0.12, p<0.10; ER: B=1.46, p<0.10; Table 3). Follow-up analyses using the Aiken and West (1991) method demonstrated that high levels of IQ were associated with child positive social adjustment only in the context of moderate risk (B=0.11, p<0.05); there was no relation between ER and positive adjustment within any of the different levels of risk. Consistent with hypotheses, the interaction between RPRQ and the lowest disadvantage trajectory was significant when descending disadvantage was the reference group (B=0.05, p<0.05; Table 4). This indicates that the relationship between RPRQ and positive social adjustment significantly differed for children in the lowest versus high descending disadvantage group. Follow-up analyses using the Aiken and West (1991) method examined the significance of the simple slopes within each trajectory group, revealing that there was a significant positive relationship between RPRQ and child social adjustment only at the lowest level of disadvantage (B= 0.02, p<0.05; Fig. 2). Thus, for children at greater than the lowest level of neighborhood disadvantage there was no relationship between high levels of parental RPRQ and child positive social adjustment. No other significant interactions between the family factors and neighborhood disadvantage were found (Tables 3 and 5).

Table 3.

Summary of logistic regression analyses predicting child positive social adjustment from child factors with neighborhood disadvantage as a moderator

| Chronic risk vs. other neighborhood groups |

High desc. risk vs. other neighborhood groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | B | SE | Wald | OR | Independent Variables | B | SE | Wald | OR |

| Child IQ | |||||||||

| IQ | 0.09 | 0.06 | 2.43 | 1.09 | IQ | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.99 |

| Lowest risk | 0.81 | 0.63 | 1.66 | 2.23 | Lowest risk | 1.91 | 0.92 | 4.30* | 6.77 |

| Low risk | 0.32 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 1.38 | Low risk | 1.43 | 0.92 | 2.45 | 4.18 |

| Moderate risk | −0.27 | 0.69 | 0.15 | 0.77 | Moderate risk | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 2.32 |

| High desc. risk | −1.11 | 1.03 | 1.17 | 0.33 | Chronic risk | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.17 | 3.03 |

| IQ×lowest risk | −0.09 | 0.06 | 1.87 | 0.92 | IQ×lowest risk | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 1.02 |

| IQ×low risk | −0.08 | 0.06 | 1.60 | 0.93 | IQ×low risk | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 1.03 |

| IQ×moderate risk | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.02 | IQ×moderate risk | 0.12 | 0.07 | 2.76** | 1.13 |

| IQ×high desc. risk | −0.10 | 0.08 | 1.89 | 0.90 | IQ×chronic risk | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.89 | 1.11 |

| Child emotion regulation (ER) | |||||||||

| ER | 43.76 | 6792.84 | 0.00 | 1.0E+19 | ER | −0.90 | 0.79 | 1.30 | 0.41 |

| Lowest risk | 52.59 | 7969.02 | 0.00 | 6.9E+22 | Lowest risk | 1.86 | 0.99 | 3.54* | 6.39 |

| Low risk | 52.35 | 7969.02 | 0.00 | 5.4E+22 | Low risk | 1.62 | 0.98 | 2.73* | 5.05 |

| Moderate risk | 51.19 | 7969.02 | 0.00 | 1.7E+22 | Moderate risk | 0.46 | 1.07 | 0.19 | 1.58 |

| High desc. risk | 50.73 | 7969.02 | 0.00 | 1.1E+22 | Chronic risk | −50.73 | 7969.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ER×lowest risk | −43.72 | 6792.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ER×lowest risk | 0.94 | 0.81 | 1.34 | 2.57 |

| ER×low risk | −43.77 | 6792.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ER×low risk | 0.89 | 0.81 | 1.21 | 2.44 |

| ER×moderate risk | −43.20 | 6792.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ER×moderate risk | 1.46 | 0.88 | 2.74* | 4.31 |

| ER×high desc. risk | −44.66 | 6792.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ER×chronic risk | 44.66 | 6792.84 | 0.00 | 2.5E+19 |

p<0.10

p<0.05

Table 4.

Summary of logistic regression analyses predicting child positive social adjustment from rprq with neighborhood disadvantage as a moderator

| Chronic risk vs. other neighborhood groups |

High desc. risk vs. other neighborhood groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | B | SE | Wald | OR | Independent Variables | B | SE | Wald | OR |

| RPRQ | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 1.01 | RPRQ | −0.03 | 0.02 | 1.77 | 0.97 |

| Lowest risk | 1.36 | 0.63 | 4.70** | 3.88 | Lowest risk | 1.71 | 0.785 | 4.06** | 5.55 |

| Low risk | 0.89 | 0.61 | 2.15 | 2.45 | Low risk | 1.25 | 0.84 | 2.23 | 3.50 |

| Moderate risk | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.06 | 1.18 | Moderate risk | 0.53 | 0.89 | 0.35 | 1.69 |

| High desc. risk | −0.36 | 0.97 | 0.14 | 0.70 | Chronic risk | 0.36 | 0.97 | 0.14 | 1.43 |

| RPRQ×lowest risk | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 1.01 | RPRQ×lowest risk | 0.05 | 0.03 | 4.72** | 1.06 |

| RPRQ×low risk | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.00 | RPRQ×low risk | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.62 | 1.04 |

| RPRQ×moderate risk | −0.03 | 0.02 | 1.32 | 0.97 | RPRQ×moderate risk | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 1.01 |

| RPRQ×high desc. risk | −0.04 | 0.03 | 1.90 | 0.96 | RPRQ×chronic risk | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 1.04 |

p<0.05

Fig. 2.

Relation between RPRQ and positive social adjustment at two levels of neighborhood disadvantage

Table 5.

Summary of logistic regression analyses predicting child positive social adjustment from parenting factors with neighborhood disadvantage as a moderator

| Chronic risk vs. other neighborhood groups |

High desc. risk vs. other neighborhood groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | B | SE | Wald | OR | Independent Variables | B | SE | Wald | OR |

| Maternal nurturance (Nurt) | |||||||||

| Nurt | 0.19 | 0.18 | 1.10 | 1.20 | Nurt | 0.49 | 0.30 | 2.66 | 1.62 |

| Lowest risk | 1.00 | 0.60 | 2.79* | 2.71 | Lowest risk | 0.97 | 0.78 | 1.54 | 2.64 |

| Low risk | 0.50 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 1.65 | Low risk | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.38 | 1.61 |

| Moderate risk | 0.19 | 0.63 | 0.09 | 1.21 | Moderate risk | 0.16 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 1.18 |

| High desc. risk | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 1.03 | Chronic risk | −0.03 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Nurt×lowest risk | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.97 | Nurt×lowest risk | −0.33 | 0.32 | 1.03 | 0.72 |

| Nurt×low risk | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 1.04 | Nurt×low risk | −0.26 | 0.32 | 0.67 | 0.77 |

| Nurt×moderate risk | −0.11 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.89 | Nurt×moderate risk | −0.41 | 0.32 | 1.66 | 0.66 |

| Nurt×high desc. risk | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 1.35 | Nurt×chronic risk | −0.30 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 0.74 |

| Parent–child relationship quality (PCRQ) | |||||||||

| PCRQ | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 1.29 | PCRQ | 1.44 | 0.85 | 2.84* | 4.21 |

| Lowest risk | 1.20 | 0.57 | 4.43** | 3.32 | Lowest risk | 1.48 | 0.87 | 2.92* | 4.41 |

| Low risk | 0.75 | 0.57 | 1.70 | 2.11 | Low risk | 1.03 | 0.87 | 1.40 | 2.80 |

| Moderate risk | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.28 | 1.39 | Moderate risk | 0.61 | 0.90 | 0.46 | 1.84 |

| High desc. risk | −0.28 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.75 | Chronic risk | 0.28 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 1.33 |

| PCRQ×lowest risk | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.16 | 1.28 | PCRQ×lowest risk | −0.93 | 0.92 | 1.03 | 0.39 |

| PCRQ×low risk | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 1.58 | PCRQ×low risk | −0.72 | 0.92 | 0.62 | 0.49 |

| PCRQ×moderate risk | 0.20 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 1.22 | PCRQ×moderate risk | −0.98 | 0.91 | 1.15 | 0.38 |

| PCRQ×high desc. Risk | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.39 | 3.25 | PCRQ×chronic risk | −1.18 | 1.00 | 1.39 | 0.31 |

p<0.10

p<0.05

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine relations among multiple child and family protective factors, neighborhood disadvantage, and positive social adjustment in a sample of urban, low SES boys followed from infancy to early adolescence. This study also addressed whether the benefits of protective factors might vary depending on both the duration and the severity of neighborhood disadvantage. In line with hypotheses, child IQ, parental nurturance, and parent–child relationship quality were found to be associated with positive social adjustment in early adolescence. When interactions between individual protective factors and neighborhood disadvantage trajectories were investigated to test the moderating role of neighborhood disadvantage status in the prediction of positive social adjustment, only parental romantic partner relationship quality (RPRQ) was found to reliably interact with neighborhood disadvantage. High levels of RPRQ were significantly related to positive outcomes only for boys in neighborhoods characterized by relatively low risk (i.e., lowest disadvantage group).

Direct Associations between Protective Factors and Positive Social Adjustment

The finding that high levels of child and family protective factors were associated with positive social adjustment corroborates other literature on protective factors (e.g., Masten et al. 1999; White et al. 1989). Indeed, child IQ and parenting variables are among the most consistently found factors associated with prosocial outcomes for children (Yates et al. 2003). Researchers have posited that high levels of intelligence can help children contend with the stressors that they encounter in their everyday lives (Masten and Coatsworth 1998). Similarly, nurturant, supportive parenting and a positive, close relationship with a parent may help children to navigate a stressful environment by providing them with valuable interpersonal and social resources (Masten and Coatsworth 1998).

Moderating Role of Neighborhood Disadvantage Trajectories

RPRQ was the only protective factor that significantly interacted with neighborhood disadvantage to predict positive social adjustment. High levels of RPRQ were only associated with positive outcomes for those children in the lowest neighborhood disadvantage trajectory. In contrast with expectations, neighborhood disadvantage did not moderate the relationship between child IQ, emotion regulation, nurturant parenting, and parent–child relationship quality assessed in early childhood and positive social adjustment in early adolescence. This suggests that these latter protective factors work similarly across levels of neighborhood disadvantage.

These findings are important for two reasons. First, we found only limited support for the notion that selected child and family protective factors appear to be more salient in contexts of lesser versus greater neighborhood disadvantage. In fact, three of the five protective factors explored in this study were associated with child positive outcome regardless of the level of neighborhood disadvantage. The fact that these protective factors are operating at lower levels of risk is consistent with our predictions. However, because of the high risk nature of our sample, we did not expect that these factors would continue to be as strongly associated with positive outcomes at the highest levels of risk. For example, Gorman-Smith et al. (1999) found that family and parenting variables were not associated with outcomes for children in the highest risk neighborhoods (i.e., the inner city), although they were for children at lower levels of risk (i.e., urban disadvantage). It is important to note, however, these authors did not actually find a significant interaction between family and parenting variables, and neighborhood risk; rather, they computed separate regressions within each neighborhood type.

Second, the finding that high levels of RPRQ were associated with positive social adjustment for children only in the lowest neighborhood disadvantage trajectory suggests the possibility of a ceiling effect. More specifically, high levels of RPRQ were not associated with positive outcomes for children at the other four higher levels of disadvantage. For children at high levels of neighborhood disadvantage, RPRQ may be less critical to their adjustment relative to other stressors in their daily lives (e.g., exposure and/or threat of violence in the neighborhood and school). RPRQ may also be somewhat removed from the immediate context of the child's life. Consequently, it may be less able to offset risk in other areas than a more proximal and all-encompassing protective factor such as child IQ, which may come into play across more situations. For example, a non-conflictual relationship between parents may help a child to feel confident and safe in the home, but it might not be enough to counteract multiple risks that the child is exposed to outside of the home. Thus, RPRQ may be more easily overwhelmed in the context of high risk than other more proximal protective factors that may impact more areas of the child's life.

Previous research has found that marital quality is associated with low levels of child emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., Belsky et al. 1991; Cummings et al. 2004), but there is a dearth of information on whether this relation is moderated by the level of neighborhood disadvantage. More generally, however, the finding that positive family functioning may not serve a protective function at high levels of risk is corroborated by several studies (e.g., Li et al. 2007). For example, a study of predominantly ethnic minority, low-income boys found that low family conflict was only protective in the context of low community violence exposure (Miller et al. 1999). Similarly, Shaw et al. (2004) found that while high family hierarchical structure (i.e., setting firm limits) served a protective function in relation to adolescent antisocial behavior among European American youth living in average to moderate levels of neighborhood adversity, this protective effect was not found for African American youth living in the highest risk neighborhoods (i.e., projects).

Trajectories of Neighborhood Risk

One of the strengths of the current study is that an objective, dynamic measurement of neighborhood disadvantage was used to define adversity. Neighborhood disadvantage was defined using US Census Bureau statistics at multiple timepoints, allowing for measurement of the chronicity and course of neighborhood disadvantage. Although it has correctly been pointed out that utilizing census data to define neighborhood disadvantage arbitrarily imposes boundaries on social contexts, it does eliminate potential reporter bias that might have occurred if we had relied on parental reports. Most families in the study did not vary significantly over time in their level of risk, but the two highest disadvantage trajectories had negative linear slopes, indicating that for these families neighborhood disadvantage decreased significantly over time. In particular, by the age 10 assessment the high descending disadvantage trajectory had decreased to levels below that of the moderate risk trajectory. Indeed, the interaction between RPRQ and neighborhood disadvantage was found in reference to the high descending disadvantage group, suggesting that this was important pattern of risk that differed from the others.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to the present study that should be noted. First, participants were low-income, urban boys; it is unclear whether these results would generalize to girls or to children living in rural or suburban areas. Indeed, research suggests that pathways to externalizing behavior may be somewhat different for girls (Pepler and Craig 2005). Given the importance of studying both conduct disorder and the effects of neighborhood on girls, future studies should include both boys and girls. Similarly, protective factors associated with positive outcomes and resilience processes may also differ by child gender and geographic context.

Second, due to low SES, the majority of the families in the study could be conceptualized as high-risk, thus it is not possible to say whether the direct relations between the protective factors and positive social adjustment hold for less economically deprived groups, or whether different or more robust interactions would have been identified within a sample covering a broader range of SES. However, as Seidman and Pedersen (2003) have pointed out, high-risk samples such as the current one allow within-group heterogeneity to be examined more closely, which can further explicate resilience processes and highlight variability in trajectories for at-risk children. Third, sample sizes within the highest two trajectory groups were considerably smaller than the other groups, which limited power and the possibility of finding interactions between protective factors and neighborhood disadvantage.

Fourth, as previously noted, unmarried mothers were allowed to complete the marital quality questionnaire on another romantic relationship, such as their boyfriend or girlfriend. This was sensitive to the fact that a little under half of the mothers in our study were unmarried and allowed for the collection of important information on the mothers’ satisfaction in their romantic relationship. However, due to differences in measurement with other studies, the current findings regarding RPRQ may not be generalizable to other samples.

Summary and Clinical Implications

This study provides important information on the relations among early child and protective factors, neighborhood disadvantage, and positive social adjustment in urban, low-SES boys. These findings highlight the importance of examining both main effects and interactions, as both provide important information for prevention and intervention efforts. It is critical to know which groups may benefit from a given intervention, whether it be all groups or specific subsets.

Consistent with prior research, the current findings emphasize the importance of child IQ and the family environment in promoting children's positive social adjustment, but contrary to other studies do not suggest that such factors are more important for children living in lower risk contexts. The results suggest that prevention programs focusing on providing young children with cognitively stimulating and nurturing environments would seem to hold promise for promoting positive outcomes, even into early adolescence, for children from low-income contexts across a range of adversity. It remains unclear, however, whether modifying one protective factor is sufficient to improve outcome, particularly in the context of high risk; interventions targeting multiple domains may prove more successful at counteracting the multiple risks associated with neighborhood adversity (Henggeler 1999; Shaw et al. 2006). Future research on the relations between multiple domains of protective factors, neighborhood disadvantage, and positive adjustment is needed, particularly in girls, and in boys and girls from rural and suburban contexts. Only through continued research on the conditions under which at-risk children achieve positive outcomes can resilience processes be fully understood and incorporated into prevention and intervention programs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants awarded to the second author from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH50907 and MH01666). The authors would like to thank Susan B. Campbell, Mark T. Greenberg, Robert McCall, Jennifer Silk, Emily Skuban, and Chris Trentacosta for their comments on earlier versions of this article; Bobby Jones and JeeWon Cheong for their statistical consultation; Emily B. Winslow and Madeleine Root for their help in collecting census data; and finally the research assistants and families of the Pitt Mother and Child Project who made this possible.

Contributor Information

Ella Vanderbilt-Adriance, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, 210 South Bouquet St., 4425 Sennott Square, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA e-mail: elv4@pitt.edu.

Daniel S. Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, 210 South Bouquet St., 4101 Sennott Square, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Parent, infant, and social–contextual antecedents of father–son attachment security. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:905–913. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Youngblade L, Rovine M, Volling B. Patterns of marital change and parent–child interaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH. Children's home environments, health, behavior, and intervention efforts: A review using the HOME inventory as a marker measure. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 1993;119:437–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Home observation for measurement of the environment. University of Arkansas at Little Rock; Little Rock: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: A multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:477–498. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C, Smith KD. Expressive control during a disappointment: Variations related to preschoolers’ behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Criss MM, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Lapp AL. Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children's externalizing behavior: A longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child Development. 2002;73:1220–1237. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. Everyday marital conflict and child aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:191–202. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019770.13216.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65:296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, Guthrie IK, Jones S, et al. Contemporaneous and longitudinal prediction of children's social functioning from regulation and emotionality. Child Development. 1997;68:642–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Forehand R. Parental divorce and children's well-being: A focus on resilience. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, et al., editors. Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, O'Leary KD. Children's perceptions of marital discord and behavior problems of boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1982;10:11–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00915948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan DP, Alfonso VC. A critical review of the technical characteristics of new and recently revised intelligence tests for preschool children. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1995;13:66–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS, Beck JE, Schonberg MA, Lukon JL. Anger regulation in disadvantaged preschool boys: Strategies, antecedents, and the development of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:222–235. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan P, Henry D. The relation of community and family to risk among urban-poor adolescents. In: Cohen P, Slomkowski C, Robins L, editors. Historical and geographic influences on psychopathology. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. pp. 349–367. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social skills rating system manual. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Bridges LJ, Connell JP. Emotion regulation in 2-year-olds: Strategies and emotional expression in four contexts. Child Development. 1996;67:928–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW. Multisystemic therapy: An overview of clinical procedures, outcomes, and policy implications. Child Psychology & Psychiatry Review. 1999;4:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hershorn M, Rosenbaum A. Children of marital violence: A closer look at the unintended victims. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:260–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb03440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS, Garcia MM. Intrafamily conflict in relation to boys’ adjustment at school. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:35–52. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Children and youth in neighborhood contexts. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li ST, Nussbaum KM, Richards MH. Risk and protective factors for African American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Schmaling KB. The utility of differentiating between mixed and pure forms of antisocial child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1985;13:315–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00910651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen W, Farrington D. Development of a new measure of self-reported antisocial behavior in young children: Prevalence and reliability. In: Klein MW, editor. Cross-national research in self-reported crime and delinquency. Kluwer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1989. pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Vulnerability and resilience: A study of high-risk adolescents. Child Development. 1991;62:600–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Zelazo LB. Research on resilience: An integrative review. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 510–549. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin RS. An ethological–cognitive model for the attenuation of mother–infant attachment behavior. In: Alloway TM, Krames L, Pliner P, editors. Advances in the study of communication and affect: The development of social attachments. Vol. 3. Plenum; New York: 1977. pp. 25–60. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56:227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from successful children. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Hubbard JJ, Gest SD, Tellegen A, Garmezy N, Ramirez M. Competence in the context of adversity: Pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:143–169. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Reed MJ. Resilience in development. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LS, Wasserman GA, Neugebauer R, Gorman-Smith D, Kamboukos D. Witnessed community violence and antisocial behavior in high-risk, urban boys. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:2–11. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Harvard; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL. Prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses: From randomized trials to community replication. Prevention Science. 2002;3:153–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1019990432161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler DJ, Craig WM. Aggressive girls on troubled trajectories: A developmental perspective. In: Pepler DJ, editor. Development and treatment of girlhood aggression. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Steinberg M, Rollins K. The first two years of school: Teacher–child relationships and deflections in children's classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Porter CL, Wouden-Miller M, Silva SS, Porter AE. Marital harmony and conflict: Links to infants’ emotional regulation and cardiac vagal tone. Infancy. 2003;4:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Radke-Yarrow M, Brown E. Resilience and vulnerability in children of multiple-risk families. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler JM. Assessment of children. 3rd ed. Sattler; San Diego: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Pedersen S. Holistic contextual perspectives on risk, protection, and competence among low-income urban adolescents. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 318–342. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Criss MM, Schonberg MA, Beck JE. The development of family hierarchies and their relation to children's conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:483–500. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of the early conduct problems: Two-year effects of the Family Check-Up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Whalen DJ, Ryan ND, et al. Resilience among children and adolescents at risk for depression: Mediation and moderation across social and neurobiological contexts. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:841–865. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Wei E, Farrington DP, Wikström PH. Risk and promotive effects in the explanation of persistent serious delinquency in boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:111–123. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Briggs PF. Old wine in new skins: Grouping Wechsler subtests into new scales. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1967;31:499–506. doi: 10.1037/h0024963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Taylor T. Nipping early risk factors in the bud: Preventing substance abuse, delinquency, and violence in adolescence through interventions targeted at young children (0−8 years). Prevention Science. 2001;2:165–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1011510923900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence—Revised. The Psychological; San Antonio: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Smith RS. Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- White JL, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. A prospective replication of the protective effects of IQ in subjects at high risk for juvenile delinquency. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:719–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikström PO, Loeber R. Do disadvantaged neighborhoods cause well-adjusted children to become adolescent delinquents? A study of male juvenile serious offending, individual risk and protective factors, and neighborhood context. Criminology. 2000;38:1109–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow EB. Development of boys’ early conduct problems in a low-income, urban sample: Implications of neighborhood context and maternal parenting. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2001;62:2509. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA, Cowen EL, Work WC, Hoyt-Meyers L, Magnus KB, Fagen DB. Caregiving and developmental factors differentiating young at-risk urban children showing resilient versus stress-affected outcomes: A replication and extension. Child Development. 1999;70:645–659. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates TM, Egeland B, Sroufe LA. Rethinking resilience: A developmental process perspective. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 243–266. [Google Scholar]