Abstract

Class B1 (secretin family) G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) modulate a wide range of physiological functions, including glucose homeostasis, feeding behavior, fat deposition, bone remodeling, and vascular contractility. Endogenous peptide ligands for these GPCRs are of intermediate length (27–44 aa) and include receptor affinity (C-terminal) as well as receptor activation (N-terminal) domains. We have developed a technology in which a peptide ligand tethered to the cell membrane selectively modulates corresponding class B1 GPCR-mediated signaling. The engineered cDNA constructs encode a single protein composed of (i) a transmembrane domain (TMD) with an intracellular C terminus, (ii) a poly(asparagine-glycine) linker extending from the TMD into the extracellular space, and (iii) a class B1 receptor ligand positioned at the N terminus. We demonstrate that membrane-tethered peptides, like corresponding soluble ligands, trigger dose-dependent receptor activation. The broad applicability of this approach is illustrated by experiments using tethered versions of 7 mammalian endogenous class B1 GPCR agonists. In parallel, we carried out mutational studies focused primarily on incretin ligands of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. These experiments suggest that tethered ligand activity is conferred in large part by the N-terminal domain of the peptide hormone. Follow-up studies revealed that interconversion of tethered agonists and antagonists can be achieved with the introduction of selected point mutations. Such complementary receptor modulators provide important new tools for probing receptor structure–function relationships as well as for future studies aimed at dissecting the tissue-specific biological role of a GPCR in vivo (e.g., in the brain vs. in the periphery).

Keywords: agonist, antagonist, GPCR, incretins, peptide hormones

Class B1 G protein-coupled receptors comprise a physiologically important subgroup of peptide hormone receptors. These 7-transmembrane domain (TMD) proteins are distinguished by a unique set of signature motifs and a lack of homology with other GPCR classes, such as class A (rhodopsin family) receptors (1). Peptides acting on class B1 receptors modulate a wide range of biological functions, including the control of insulin release [e.g., glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP)], calcium homeostasis and bone remodeling [e.g., parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcitonin], as well as vascular reactivity [e.g., calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)] (2).

Many studies on class B1 GPCRs support a 2-domain model for hormone recognition and receptor activation. The corresponding peptide ligands are of intermediate length (27–44 aa). It is postulated that the C-terminal portion of the peptide binds the N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) of the receptor; this interaction at least in part defines both ligand affinity and specificity. As a second step, the N-terminal segment of the hormone interacts with the receptor TMDs and connecting extracellular loops, triggering intracellular signal transduction (2). Recent studies revealed the crystal structure of ECD–peptide hormone complexes, providing important insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying PTH (3), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) (4), GIP (5), and exendin-4 (EXE4) (6) interaction with their corresponding GPCRs. Notably, these reports highlight that each of the peptides docks as an amphipathic α-helix in a hydrophobic groove present in the receptor ECD.

Peptide ligands that modulate class B1 GPCR function hold considerable promise as therapeutics. The peptidic GLP-1 mimetic EXE4 (also known as exenatide or BYETTA) activates the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) and represents the first incretin-based pharmaceutical for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (7). Recombinant PTH and calcitonin, targeting their corresponding GPCRs, are injected daily as a treatment option for osteoporosis (2). Other drugs that either mimic or block the function of endogenous class B1 ligands represent promising therapeutics for a range of disease, including migraine (CGRP) (8), short bowel syndrome (GLP-2) (9), inflammation (vasoactive intestinal peptide) (10), and stress-related disorders (CRF) (11).

Despite successes in identifying a number of efficacious peptides, optimization of surrogate agonists (e.g., improving resistance to enzymatic degradation) and/or the development of high-affinity antagonist derivatives is a challenging process. A better knowledge of the specific interactions between the N-terminal activator domain of the hormones and the transmembrane core of class B1 GPCRs will expedite the discovery and optimization of the next generation of peptide ligands.

In this study, we report the development of a previously unexplored paradigm, membrane-tethered peptides, which can be used as probes to explore class B1 ligand–receptor interactions. We demonstrate that such ligands are highly functional and receptor-selective. The recombinant nature of these constructs enables expeditious mutational analysis, thereby facilitating the identification/optimization of tethered agonists and antagonists. For class B1 peptides, the broad applicability of this approach makes it a powerful tool to study mammalian receptor function, both in vitro and in vivo.

Results and Discussion

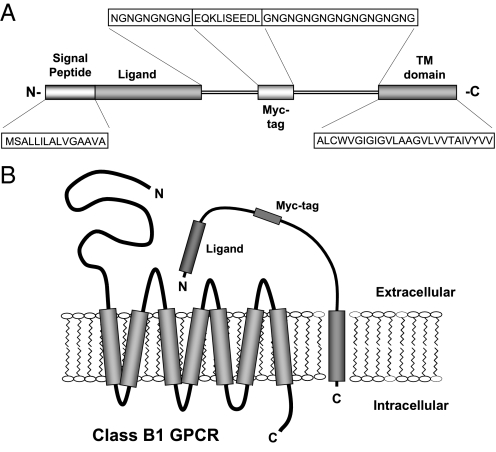

The current study explores the potential of membrane-tethered peptides as modulators of mammalian class B1 GPCRs. These genetically engineered cDNA constructs encode a single protein composed of (i) a type I TMD anchor (12), (ii) a flexible peptide linker extending from the TMD into the extracellular space, (iii) a myc epitope tag inserted into the linker, (iv) a class B1 receptor ligand, and (v) a signal peptide positioned at the N terminus of the processed protein (Fig. 1A). Multiple studies support that the N terminus of secretin-like peptides is important in mediating ligand-induced receptor activation (13, 14). Utilization of a type I TMD ensures that membrane insertion will occur such that the N terminus of the construct is extracellular and the C terminus is intracellular (12). Inclusion of the signal peptide favors proper membrane insertion of the construct. During protein processing, the signal peptide is cleaved, leaving the tethered ligand with a free N terminus (15). We hypothesized that membrane-tethered ligands projecting into the extracellular space will modulate the activity of coexpressed class B1 GPCRs (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of a membrane-tethered ligand. (A) Protein domains encoded by the tethered ligand constructs. Amino acids are indicated by the single-letter code. (B) A schematic representation of tethered ligand–receptor interaction.

Membrane-Tethered Ligands Trigger GPCR Signaling.

All mammalian class B1 receptors are predominantly coupled to stimulatory Gαs proteins, leading to agonist-induced elevation in intracellular cAMP (2). In this study, receptor-mediated signaling was assessed by using a CRE6x luciferase reporter gene construct (a multimerized cAMP response element ligated upstream from a firefly luciferase reporter gene) (16).

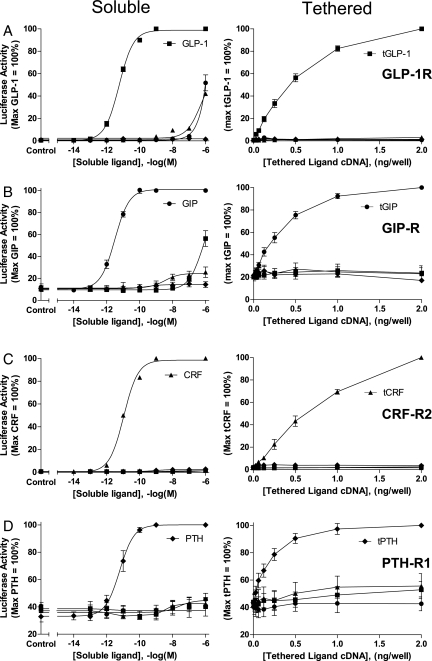

In cells coexpressing a tethered hormone and a corresponding GPCR, receptor-mediated signaling increased as a function of tethered ligand expression (Fig. 2). As with the corresponding soluble hormones, a high degree of specificity existed in the interaction between receptor and tethered ligand, as illustrated for GLP-1R, GIPR, PTH-R1, and CRF-R2. Characterization of additional tethered ligands, including glucagon, GLP-2, and CGRP, also showed expression-dependent activation of corresponding GPCRs (Fig. S1). It is of note that one construct design (with the same TMD and linker length) is able to accommodate a wide range of endogenous peptides, each able to trigger efficacious signaling at its cognate receptor. The applicability of this approach to a majority of mammalian receptors in this family further supports that common molecular mechanisms underlie ligand-induced activation of class B1 GPCRs.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of soluble versus tethered ligand-induced activation of corresponding GPCRs. Soluble ligand concentration–response (Left) and tethered ligand cDNA–activity (Right) curves are compared. HEK293 cells expressing the receptors (A) GLP-1R, (B) GIP-R, (C) CRF-R2, or (D) PTH-R1 were stimulated with either soluble or tethered ligands. All 4 ligands, GLP-1, GIP, CRF, and PTH, were assessed at each receptor. Each graph represents data (mean ± SEM) from 3–6 independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. The pEC50 (negative logarithm of the half-maximal effective concentration) values of soluble ligands at corresponding GPCRs were as follows: GLP-1 (11.24 ± 0.05), GIP (11.51 ± 0.07), PTH (11.21 ± 0.27), and CRF (11.00 ± 0.04); n = 3, mean ± standard deviation.

Tethered peptide-induced activation of the corresponding receptor led to signaling ranging from 35–100% of the soluble hormone-induced maximum (Fig. S2). It is possible that with further modification (e.g., tether length and TMD composition), tethered ligands with even higher activity may be generated. Alternatively, adaptation mechanisms, including receptor endocytosis, desensitization, and down-regulation (17), may limit the degree of tethered ligand-induced signaling at selected GPCRs.

Further studies examining receptor activation by a tethered ligand focused on the GLP-1R, a representative member of the B1 GPCR family. This receptor is of particular interest, given its important role in the physiological maintenance of blood glucose homeostasis (18). As shown in Fig. 2A, GLP-1 is a high-potency, soluble GLP-1R agonist that also acts as a tethered activator of receptor-mediated signaling. In contrast, the low-potency ligands, CRF and GIP, activated the GLP-1R as soluble ligands (Fig. 2A Left), but not as tethered constructs (Fig. 2A Right). As a possible explanation for this difference, the local concentration of a low-potency hormone achieved with expression of a tethered construct (e.g., tGIP or tCRF) may not reach a level (i.e., micromolar) sufficient to activate the GLP-1R. Alternatively, tethered ligands may be less flexible than corresponding soluble forms, and they may thus be unable to adopt the optimal positioning required to trigger receptor activation.

Selected Amino Acids in the N-Terminal Peptide Domain Define Tethered Ligand Activity.

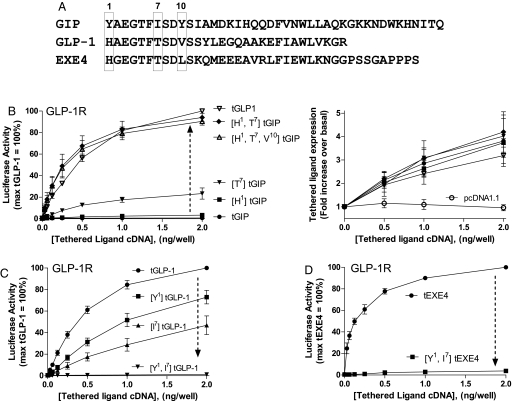

To further explore how tethered ligands modulate the function of cognate receptors, we analyzed the effects of amino acid substitutions within the N-terminal domain of the peptide (Fig. 3). These studies focused on tethered variants of 3 related GLP-1R ligands: GLP-1 and EXE4 (each with subnanomolar potency at the GLP-1R), as well as GIP (a low-potency activator of the GLP-1R; Fig. 2). Comparison of the corresponding amino acid sequences revealed that the N termini were highly conserved (6 of 10 residues were identical), whereas the C termini were highly divergent (Fig. 3A). As tethered constructs, both GLP-1 and EXE4 were strong agonists, whereas GIP lacked activity (Fig. 3 B and D). Based on the 2-domain model of ligand–receptor interaction (14), we hypothesized that the N terminus of the tethered peptide confers efficacy.

Fig. 3.

Two N-terminal peptide amino acids define the efficacy of tethered GIP, GLP-1, and EXE4 at the GLP-1R. (A) Sequence comparison of human GIP, GLP-1, and EXE4 hormones. Position 1 represents the N-terminal residue of the peptides. Within the first 10 aa, GIP and GLP-1 differ at positions 1, 7, and 10 (boxes). (B) (Right) Comparable cell surface expressions of tGIP, [H1]tGIP, [T7]tGIP, [H1,T7]tGIP, and tGLP-1, as assessed by ELISA. (Left) A 2-amino acid substitution in tGIP is sufficient to increase activity to a level comparable to tGLP-1. (C) A 2-amino acid substitution into tGLP-1 eliminates tethered ligand-induced signaling at the GLP-1R. (D) A 2-amino acid substitution into tEXE4 eliminates tethered ligand-induced signaling at the GLP-1R. Graphs represent the mean ± SEM. from 3 or 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

To assess the relative importance of specific residues in the N-terminal domain of the peptide, a series of tethered analogs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis and tested at the GLP-1R. The GLP-1 residues at positions 1, 7, and 10 were substituted for corresponding amino acids in the tGIP sequence, either alone or in combination (Fig. 3B Left). Replacement of Y1 by H1 conferred only trace activity (3.4% ± 2%), whereas introduction of T7 in place of I7 led to ligand-induced signaling approximating one quarter (23.4% ± 9%) of the tGLP-1-induced maximum. A tGIP analog that included both H1 and T7 mutations was comparable to tGLP-1 in activating the GLP-1R (94.0% ± 1%). Of note, introduction of V10 into tGIP in combination with H1 and T7 did not further influence activity (Fig. 3B).

ELISA assays were carried out on nonpermeabilized HEK293 cells to evaluate tethered peptide expression on the extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane. Expression of the tGIP derivatives was comparable to unmodified tGIP and tGLP-1, suggesting that the observed variations in activity were not due to alterations in tethered peptide levels (Fig. 3B Right). Of note, the converse substitutions (Y1, I7 replacing H1, T7) in either tGLP-1 or tEXE4 led to a complete loss of tethered ligand activity (Fig. 3 C and D). Taken together, these results further support the emerging view that the N-terminal peptide domain is important in defining ligand efficacy (14).

The residues that confer activity to soluble versus tethered ligands appear to share significant overlap (19). A previously published alanine scan of soluble GLP-1 demonstrated that H1 and T7 were among the important determinants of ligand function (20). Further support for overlap in functional residues (soluble vs. tethered) stems from another study showing that introduction of 3 N-terminal GLP-1 amino acids, H1, T7, and V10, into the homologous position of soluble GIP converted this peptide into a fully efficacious agonist at the GLP-1R (21). The tethered GIP equivalent (H1, T7, and V10 substituted), as assessed in the present study, is also a highly efficacious peptide, whereas tGIP has no activity (Fig. 3B). Extending current understanding, our findings suggest that among the 3 previously studied residues, it is H1 and T7 that confer agonist activity at the GLP-1R.

Reminiscent of the apparent synergy between the H and T residues in [H1,T7]tGIP-induced activation of the GLP-1R, cooperative contributions of different functional groups have been shown to define affinity and efficacy of class A GPCR agonists; e.g., in epinephrine derivatives (22). To our knowledge, few studies have systematically analyzed the synergistic effects of combined amino acid substitutions on the function of secretin-like ligands; such knowledge could prove useful for the rational design of synthetic ligands.

Discovery of Tethered GLP-1R Antagonists.

In addition to the synergistic contribution to tethered peptide activity, we noted an additive loss of function with sequential substitution of Y1 and I7 into either tGLP-1 or tEXE4. Single substitutions introducing either GIP residue, Y1 or I7, were associated with decreased function, whereas simultaneous introduction of these 2 amino acids completely abolished GLP-1R agonist activity (Fig. 3 C and D).

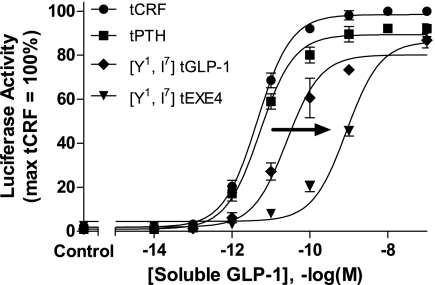

The total loss of function observed with only a double amino acid substitution raised the possibility that [Y1,I7]tGLP-1 and [Y1,I7]tEXE4 were antagonists. To evaluate this hypothesis, cells transfected overnight with cDNA encoding the GLP-1R and a tethered ligand were stimulated with increasing concentrations of soluble GLP-1. A rightward shift in the GLP-1 dose–response curve was observed in cells expressing either [Y1,I7]tEXE4 or [Y1,I7]tGLP-1 (corresponding GLP-1 potency shifts were ≈120-fold and 6-fold, respectively; Fig. 4). Despite these marked shifts, maximal efficacy (comparable to the level observed with expression of control tethered peptides) could still be achieved with high concentrations of soluble GLP-1. The observed decrease in GLP-1 potency with these constructs, together with the ability of free GLP-1 to induce maximal signaling at high concentrations, is consistent with [Y1,I7]tEXE4 and [Y1,I7]tGLP-1 being classified as competitive antagonists (Fig. 4). As negative controls, tCRF and tPTH, which display no activity at the GLP-1R (Fig. 2A) were included. Consistent with the expectation that tCRF and tPTH do not interact with this receptor, the potency of soluble GLP-1 in cells expressing either tethered construct was similar to the value obtained in cells expressing the GLP-1R alone (Figs. 2A and 4). The latter observation highlights that GLP-1R antagonism is not merely the result of coexpressing a tethered ligand, but is clearly attributable to the composition of the attached peptide (e.g., variants of either tEXE4 or tGLP-1).

Fig. 4.

Pharmacological effects of membrane-tethered antagonists at the GLP-1R. HEK293 cells, transfected overnight with the GLP-1R and selected tethered ligand cDNAs, were stimulated with increasing concentrations of soluble GLP-1. Expression of either [Y1,I7]tGLP or [Y1,I7]tEXE4 led to a rightward shift (indicated by arrow) in the concentration–activity curve of GLP-1. Data represent the mean ± SEM from 3 to 6 independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. The pEC50 values for soluble GLP-1 in the presence of tethered ligand are as follows: [Y1,I7]tGLP-1 (10.53 ± 0.25), [Y1,I7]tEXE4 (9.20 ± 0.23), tPTH (11.29 ± 0.16), and tCRF (11.31 ± 0.15); n = 3–6, mean ± standard deviation.

It is also of note that the [Y1,I7]tGLP-1 construct is much less effective than the [Y1,I7]tEXE4 derivative in blocking the actions of exogenous GLP-1. This observation is consistent with previous reports suggesting that N-terminal modifications in GLP-1 may alter both efficacy and affinity, whereas parallel changes in EXE4 have a lesser impact on affinity and primarily affect efficacy. It has been proposed that this difference may stem from the fact that GLP-1 has a less stable secondary helical structure when compared with EXE4 (6, 23).

Tethered Ligands May Bypass the N-Terminal Extracellular Domain Affinity Trap of Class B1 GPCRs.

As outlined earlier, the current model of class B1 receptor activation for soluble ligands suggests that the C terminus of the peptide binds to the ECD of the receptor (the affinity trap), whereas the N-terminal domain of the peptide triggers receptor-mediated signaling. When the N-terminal domain of tGIP was modified (transferring GLP-1 residues H1, T7, and V10 in place of the corresponding GIP amino acids), the tethered ligand was transformed from an inactive to a fully active tethered peptide at the GLP-1R (Fig. 3B). This is consistent with the N terminus of the tethered peptide defining efficacy. However, despite the major difference at the C terminus between [H1,T7,V10]GIP and GLP-1, the apparent potency of both ligands was comparable when assessed as membrane-tethered constructs (Fig. 3B). This finding contrasts with parallel experiments from the literature using soluble ligands. Soluble [H1,T7,V10]GIP is reported to have ≈1,000-fold lower GLP-1R affinity/potency compared with soluble GLP-1 (21). It thus appears that the role of the C terminus in conferring affinity is at least in part bypassed by membrane tethering, thereby enabling [H1,T7,V10]tGIP to activate the GLP-1R essentially like tGLP-1.

To explain the difference between tethered and soluble ligands, we propose that anchoring of the peptide in the vicinity of the receptor may facilitate the association between these 2 proteins, thereby enhancing the apparent potency of a low-affinity ligand. The need for an affinity trap between the N terminus of the receptor and the C-terminal domain of the tethered peptide may thus be circumvented.

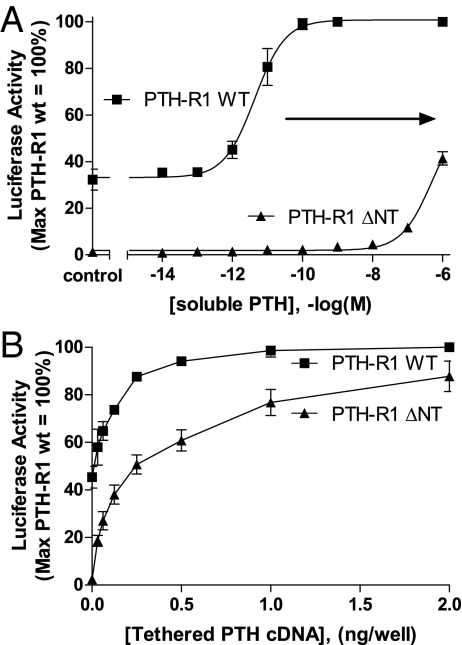

If the above hypothesis is correct, then it might be anticipated that a tethered ligand could activate a class B1 GPCR with a truncated ECD. A previously characterized parathyroid hormone receptor that lacks the majority of this domain was used to explore this possibility. At the N-terminally truncated PTH-R1 (24), soluble PTH displayed a dramatically lower potency (consistent with the absence of the high-affinity hormone docking site) than on the wild-type receptor (Fig. 5A). In contrast to soluble PTH, the apparent potency of tPTH was similar on the truncated and the wild-type PTH-R1 (Fig. 5B). These data further suggest that a membrane tether may bypass the requirement of the receptor ECD as an affinity trap by concentrating and/or stabilizing the ligand in close proximity to the target GPCR. Furthermore, the observed gain of function achieved with tethering suggests that the activity of corresponding ligands is not explained by the release of soluble peptides from these constructs.

Fig. 5.

Deletion of the PTH-R1 extracellular N-terminal domain markedly shifts the potency of soluble PTH but does not affect responsiveness to the corresponding tethered ligand. HEK293 cells expressing either the wild type or a truncated PTH-R1 (PTH-R1 ΔNT, lacking the receptor ECD) were stimulated with either soluble PTH (A) or tethered PTH (B). Results shown represent data (mean ± SEM.) from 3 to 6 separate experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Conclusions

The apparent universality of tethered ligand technology for class B1 agonists lends further support to the idea that common molecular mechanisms govern the activation of this family of GPCRs. Tethered agonists and antagonists provide tools for probing structure–function relationships between a ligand and its corresponding class B1 receptor. This strategy offers a potential approach to dissociate study of the N-terminal activation domain of a peptide from investigation of the C-terminal affinity determinants. The ability to optimize the activity of a ligand with clinical potential, independent of affinity, should facilitate the development of targeted therapeutics.

We have demonstrated that tethered ligands provide a highly selective means to activate corresponding GPCRs in vitro. Targeted expression of tethered agonists and antagonists using tissue-specific or cell type-specific promoters will enable the generation of powerful in vivo transgenic models (C.C., M.N.N., manuscript submitted). With the investigation of such animals, it will become possible to clearly dissect the role of a class B1 peptide in different tissues-e.g., the function of GLP-1 in selected regions of the CNS versus in pancreatic insulin-producing beta cells (18). In contrast to injection of a soluble ligand, tethered peptides have the advantage of not diffusing into surrounding tissue or into the circulation, thereby ensuring that observed effects can be ascribed to hormone action only on the targeted cells. Given the unique ability to selectively activate or block receptor function in specific cell populations, it can be anticipated that the application of membrane-tethered ligands will significantly expand current insight into the physiological roles of class B1 GPCRs.

Experimental Methods

Generation of Tethered Ligand and GPCR Constructs.

A cDNA encoding a membrane-tethered version of pigment-dispersing factor (PDF; a Drosophila class B1 peptide hormone) was chemically synthesized and cloned in pcDNA3.1 (C.C., M.N.N., manuscript submitted). After subcloning into pcDNA1.1, other class B1 GPCR ligand sequences were substituted in place of the PDF coding region by using oligonucleotide-directed, site-specific mutagenesis as previously described (25, 26). Point mutations were introduced into the corresponding tethered ligands by using the same mutagenesis approach. The composition of the encoded constructs is further illustrated in Fig. 1A. The signal peptide sequence was derived from preprotrypsin (15). The TMD used in the construct was derived from the human herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein C (27). Complementary DNAs encoding the following human GPCRs: GIP-R, CRF-R2, GLP-2R, glucagon receptor (GCG-R), and calcitonin-like receptor (28), as well as the receptor activity-modifying protein 1 (RAMP1) were obtained from the Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center (www.cdna.org) and subcloned in pcDNA1.1. The human GLP-1R cDNA was generated as reported previously (29). The cDNAs encoding the wild-type and truncated PTH-R1 cloned into pcDNA1 were generously provided by Thomas Gardella (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA). The nucleotide sequence of all tethered ligand and receptor coding regions were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture.

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2.

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay.

Receptor-mediated signaling was assessed by using a modified version of a previously described luciferase assay (16, 30). In brief, HEK293 cells were plated at a density of 2,000–3,000 cells per well onto clear-bottom, white, 96-well plates and grown for 2 days to ≈80% confluency. Cells were then transiently transfected by using the Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) with cDNA encoding (i) a GPCR (or empty expression vector), (ii) a tethered ligand (where applicable), (iii) a cAMP-responsive element-luciferase reporter gene (CRE6X-luc), and (iv) β-galactosidase as a control. For experiments investigating the agonist function of soluble hormones, tethered ligand cDNA was not included in the transfection reaction. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were incubated with or without the selected peptide agonist (American Peptide Company Inc.) in serum-free medium for 6 h. Following ligand stimulation, the medium was gently aspirated, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was quantified by using Steadylite reagents (Perkin–Elmer). A β-galactosidase assay then was performed after adding the enzyme substrate 2-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside. Following incubation at 37 °C for 30–60 min, substrate cleavage was quantified by measurement of optical density at 420 nM using a SpectraMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Corresponding values were used to normalize the luciferase activity data.

Assessment of Tethered Ligand Expression Using ELISA.

The surface expression levels of the myc-tagged tethered ligands were assessed by using a previously established procedure (31). HEK293 cells grown in 96-well, clear Primaria plates (BD Biosciences) were transiently transfected with increasing amounts of either pcDNA1.1 or a cDNA encoding the myc-tagged tethered ligand. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed once with PBS (pH 7.4) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After washing with 100 mM glycine in PBS, the cells were incubated for 30 min in blocking solution (PBS containing 20% bovine serum). A horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody directed against the myc epitope tag (polyclonal; 1:1,500 in blocking buffer; Abcam catalog no. ab19312) was then added to the cells. After 1 h, the cells were washed 5 times with PBS. Fifty microliters per well of a solution containing the peroxidase substrate BM-blue (3,3′-5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine; Roche Applied Science) was then added. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, conversion of this substrate by antibody-linked HRP was terminated by adding 2.0 M sulfuric acid (50 μL per well). Results were quantified by measuring light absorbance at 450 nm using a SpectraMax microplate reader.

Data Analysis.

GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad) was used for sigmoidal curve fitting of ligand concentration–response curves and for calculating the EC50 values as an index of ligand potency.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank our colleagues Kathleen Dunlap, Isabelle Draper, and Lei Ci for thoughtful discussions. We thank the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec for a Fellowship Award to J.-P.F. The work in the laboratory of A.S.K. was supported in part by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01DA020415 and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01DK072497 and R01DK074075. The work in the laboratory of M.N.N. was supported in part by the Whitehall Foundation and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants R01NS055035 and R01NS056443.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0900149106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lagerstrom MC, Schioth HB. Structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors and significance for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:339–357. doi: 10.1038/nrd2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoare SR. Mechanisms of peptide and nonpeptide ligand binding to Class B G-protein-coupled receptors. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:417–427. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pioszak AA, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of parathyroid hormone by its G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5034–5039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pioszak AA, Parker NR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of corticotropin-releasing factor by its G-protein-coupled receptor CRFR1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32900–32912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805749200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parthier C, et al. Crystal structure of the incretin-bound extracellular domain of a G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13942–13947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706404104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Runge S, Thogersen H, Madsen K, Lau J, Rudolph R. Crystal structure of the ligand-bound glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor extracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11340–11347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green BD, Flatt PR. Incretin hormone mimetics and analogues in diabetes therapeutics. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;21:497–516. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doods H, Arndt K, Rudolf K, Just S. CGRP antagonists: Unravelling the role of CGRP in migraine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mardini HE, de Villiers WJ. Teduglutide in intestinal adaptation and repair: Light at the end of the tunnel. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:945–951. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.6.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abad C, Gomariz RP, Waschek JA. Neuropeptide mimetics and antagonists in the treatment of inflammatory disease: Focus on VIP and PACAP. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:151–163. doi: 10.2174/156802606775270288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arzt E, Holsboer F. CRF signaling: Molecular specificity for drug targeting in the CNS. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou KC, Elrod DW. Prediction of membrane protein types and subcellular locations. Proteins. 1999;34:137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen SM, Nielsen LZ, Hjorth SA, Perrin MH, Vale WW. Constitutive activation of tethered-peptide/corticotropin-releasing factor receptor chimeras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10277–10281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann JM, et al. Class-B GPCR activation: Is ligand helix-capping the key? Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Kaetzel MA, Yoo SE, Kim PS, Dedman JR. Ligand-regulated secretion of recombinant annexin V from cultured thyroid epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1313–C1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00553.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Fulaij MA, Ren Y, Beinborn M, Kopin AS. Identification of amino acid determinants of dopamine 2 receptor synthetic agonist function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:298–307. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.116384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson SS. Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: The role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2131–2157. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao Q, et al. Biological activities of glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues in vitro and in vivo. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2860–2869. doi: 10.1021/bi0014498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adelhorst K, Hedegaard BB, Knudsen LB, Kirk O. Structure-activity studies of glucagon-like peptide-1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6275–6278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinke SA, et al. In depth analysis of the N-terminal bioactive domain of gastric inhibitory polypeptide. Life Sci. 2004;75:1857–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liapakis G, Chan WC, Papadokostaki M, Javitch JA. Synergistic contributions of the functional groups of epinephrine to its affinity and efficacy at the beta2 adrenergic receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1181–1190. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montrose-Rafizadeh C, et al. High potency antagonists of the pancreatic glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21201–21206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luck MD, Carter PH, Gardella TJ. The (1–14) fragment of parathyroid hormone (PTH) activates intact and amino-terminally truncated PTH-1 receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:670–680. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beinborn M, Lee YM, McBride EW, Quinn SM, Kopin AS. A single amino acid of the cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor determines specificity for non-peptide antagonists. Nature. 1993;362:348–350. doi: 10.1038/362348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blaker M, et al. Mutations within the cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor ligand ‘pocket’ interconvert the functions of nonpeptide agonists and antagonists. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:857–863. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naim HY, Roth MG. Basis for selective incorporation of glycoproteins into the influenza virus envelope. J Virol. 1993;67:4831–4841. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4831-4841.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poyner DR, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXII. The mammalian calcitonin gene-related peptides, adrenomedullin, amylin, and calcitonin receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:233–246. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tibaduiza EC, Chen C, Beinborn M. A small molecule ligand of the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor targets its amino-terminal hormone binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37787–37793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hearn MG, et al. A Drosophila dopamine 2-like receptor: Molecular characterization and identification of multiple alternatively spliced variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14554–14559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202498299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinyama H, Masuzaki H, Fang H, Flier JS. Regulation of melanocortin-4 receptor signaling: Agonist-mediated desensitization and internalization. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1301–1314. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.