Abstract

Osteoporosis is a major public health problem in men. Hypogonadal men have decreased BMD and deteriorated trabecular bone architecture compared with eugonadal men. Testosterone treatment improves their BMD and trabecular structure. We tested the hypothesis that testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men would also improve their bone's mechanical properties. Ten untreated severely hypogonadal and 10 eugonadal men were selected. The hypogonadal men were treated with a testosterone gel for 24 mo to maintain their serum testosterone concentrations within the normal range. Each subject was assessed before and after 6, 12, and 24 mo of testosterone treatment by μMRI of the distal tibia. A subvolume of each μMR image was converted to a microfinite element (μFE) model, and six analyses were performed, representing three compression and three shear tests. The anisotropic stiffness tensor was calculated, from which the orthotropic elastic material constants were derived. Changes in microarchitecture were also quantified using newly developed individual trabeculae segmentation (ITS)-based and standard morphological analyses. The accuracy of these techniques was examined with simulated μMR images. Significant differences in four estimated anisotropic elastic material constants and most morphological parameters were detected between the eugonadal and hypogonadal men. No significant change in estimated elastic moduli and morphological parameters was detected in the eugonadal group over 24 mo. After 24 mo of treatment, significant increases in estimated elastic moduli E22 (9.0%), E33 (5.1%), G23 (7.2%), and G12 (9.4%) of hypogonadal men were detected. These increases were accompanied by significant increases in trabecular plate thickness. These results suggest that 24 mo of testosterone treatment of hypogonadal men improves estimated elastic moduli of tibial trabecular bone by increased trabecular plate thickness.

Key words: osteoporosis, male hypogonadism, μMRI, individual trabeculae segmentation, finite element analysis

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis, a disease characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of trabecular microarchitecture leading to increased bone fragility, is a significant public health problem. More than 1.5 million fractures occur each year in the United States alone. The estimated annual cost of medical and nursing services related to hip fractures alone is more than $17 billion and is expected to increase exponentially with the aging of the population.(1,2) Although it is not typically seen to be as serious a problem as for women, osteoporosis in men is now also recognized as an increasingly important public health issue. Thirty percent of hip fractures occur in men and the mortality rate is twice that of women.(3) It is estimated that >2 million men in the United States have osteoporosis, whereas the lifetime risk of osteoporotic fractures in men has been estimated to be 13–25%.(4,5) Among men evaluated for osteoporosis, 5–30% have no apparent cause other than hypogonadism. Severely hypogonadal men have lower BMD than eugonadal men; testosterone replacement of severely hypogonadal men increases their BMD.(4–7)

Currently, DXA is being used widely to measure BMD and predict fracture risk. However, reliable prediction of fractures has been hampered by the significant overlap in BMD between individuals with and without osteoporotic fractures. Over the past decade, it has been recognized that factors of bone quality other than bone mass, such as microstructure and bone tissue composition, also contribute to fracture risk.(8,9) To accurately assess the individual risk of osteoporotic fractures and evaluate the progression of osteoporosis and the efficacy of its treatment, noninvasive tools are necessary to assess bone quality beyond bone mass. μCT and μMRI are high-resolution imaging modalities that are now increasingly used for quantifying microstructural changes in trabecular bone architecture.(10–15) μMRI of trabecular bone actually images the bone marrow compartment instead of bone, whereas μCT measures X-ray attenuations of bone mineral. One of the advantages of μMRI is its noninvasive property. Recently, μCT with low X-ray dose for peripheral sites has also been developed and applied to patient studies.(16) However, μMRI has the advantage that no ionizing radiation exposure is involved when imaging patients.

In assessing microstructural deterioration in trabecular bone caused by hypogonadism in men, μMRI had previously been applied to characterize distal tibial trabecular bone microarchitecture in hypogonadal and eugonadal men.(14) This work showed that the tibial trabecular bone of hypogonadal men differs from that of age- and race-matched eugonadal men in the topology of the network by having a significantly lower surface-to-curve ratio and a significantly higher erosion index. These results suggested that the bone loss in hypogonadal men is caused by a conversion of plate-like to rod-like trabeculae. However, no statistically significant difference in either spinal or hip BMD by DXA was found, supporting the importance of detecting subtle microarchitectural changes in osteoporosis early. A 24-mo hormone replacement treatment study of the same hypogonadal men indicated a significant increase in the surface-to-curve ratio and a reduction in the erosion index of tibial trabecular bone based on μMRI, as well as independent but significantly increased BMD at the hip and spine measured by DXA.(15) This study indicated that μMRI of distal tibial trabecular bone could be valuable for monitoring the efficacy of osteoporosis treatment. However, it is still not clear whether there was any deterioration in mechanical properties of tibial trabecular bone in hypogonadal patients and whether the mechanical properties of tibial trabecular bone were improved on treatment.

Taking advantage of high-resolution in vivo images of trabecular bone, the image-based finite element (FE) analysis technique allows calculation of mechanical properties of human trabecular bone in patients with osteoporosis to assess the progression of osteoporosis and the efficacy of treatment.(17–22) Recently, μMRI and image-based FE analysis of calcaneal trabecular bone from postmenopausal women, who had undergone treatment with either placebo, 5 mg, or 10 mg idoxifene for 12 mo, has shown significant changes in estimated elastic moduli despite undetectable changes in either BMD or bone volume fraction (BV/TV).(20) These data suggest that significant changes in estimated elastic moduli of trabecular bone may precede any measurable changes in BMD. Although FE analysis based on the high-resolution μCT image of trabecular bone has been validated by comparison with experimental measurements of elastic and yield properties,(23–27) only a few studies have addressed the accuracy of μMR image-based FE analysis.(18) Therefore, an evaluation of the accuracy of the estimated elastic moduli would be desirable. It is important to note that mechanical properties of trabecular bone cannot be measured noninvasively in patients but can only be estimated on the basis of high-resolution image based mechanical modeling.

With advances in high-resolution μCT imaging for trabecular bone, 3D model-independent morphological techniques have been developed during the past 10 yr, allowing quantification of model-independent trabecular thickness (Tb.Th*), trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp*), trabecular number (Tb.N*), and structure model index (SMI).(13,28,29) These standard 3D morphological analysis techniques have rarely been applied to either ex vivo or in vivo μMR images. In addition, the existing morphological analysis techniques could not explicitly segment individual trabecular plates and rods. Therefore, the exact and detailed process of pathological deterioration in osteoporosis and restoration during treatment is not completely clear. Recently, individual trabeculae segmentation (ITS)-based morphological analysis has been developed.(30–32) It may be valuable to use this new morphological analysis to determine underlying architectural changes in tibial trabecular bone of hypogonadal men in response to hormone replacement treatment.

In this study, the image-based FE method(17) was used to assess changes in the estimated elastic moduli of trabecular bone in the distal tibia on the basis of in vivo μMRI data in hypogonadal and eugonadal males published previously.(14,15) The first aim of this study was to evaluate possible differences in mechanical properties between hypogonadal and eugonadal subjects at baseline (0 mo) and to determine whether testosterone replacement of these severely hypogonadal men during a 24-mo period improved the mechanical properties of trabecular bone. The second aim was to assess the morphological changes of trabecular bone in the eugonadal and hypogonadal men using both standard and newly developed ITS-based morphological analyses.(30,32) Last, the validity of FE, ITS-based, and standard morphological analysis techniques was evaluated with the aid of high-resolution μCT images, which were downsampled to in vivo resolution to mimic those obtainable by μMRI (Appendix 1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The μMR images subjected to FE analysis were taken from two previously published studies(14,15) and had been approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pennsylvania and the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and each subject gave written informed consent before entry.(14,15) Details of patient characteristics and procedures are given elsewhere.(14,15) In brief, 10 untreated hypogonadal men who had secondary hypogonadism with an estimated duration of >2 yr and had received no testosterone treatment for at least 4 yr before enrollment were compared with 10 eugonadal men who were of similar age and were matched for race. All 10 eugonadal men had a serum testosterone concentration within the normal range and a normal BMD of the spine for age. Testosterone treatment was provided to the hypogonadal men to maintain serum testosterone concentration within the normal range (400–900 ng/dl) throughout the 24 mo. Eugonadal men did not receive any treatment but had a second determination of serum testosterone concentration at 24 mo.

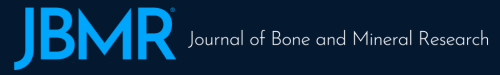

Subjects were evaluated by μMRI at 0, 6, 12, and 24 mo, yielding images from the right tibial metaphysis.(15) The acquisition voxel size was 137 × 137 × 410 μm. Subsequently, the raw images were converted to bone volume fraction maps in which the gray value represents the fractional content of bone and subvoxel-processed to enhance apparent resolution (69 × 69 × 103 μm). The resulting resolution-enhanced images were binarized using custom-designed programs.(33) Images from each subject at 6, 12, and 24 mo were registered to the baseline images (Fig. 1). Cylindrical subvolumes (7.54 mm in diameter and 5.15 mm in length) of the images at each time point for each subject were first matched for architectural features and then extracted from the binarized images to ensure that the same volume was analyzed. A parallelepiped-shaped volume of interest (VOI) of 75 × 75 × 50 voxels, corresponding to 5.18 × 5.18 × 5.15 mm, was isolated from the center of each cylindrical subvolume along the image coordinate system (Fig. 1). Single isolated voxels or a group of connected voxels not connected to the remainder of the trabecular bone microstructure were removed using principal component analysis because they do not contribute mechanically and may cause convergence problems in computations. Finally, the VOIs were subjected to the following mechanical and morphological analyses.

FIG. 1.

Anatomic site for μMRI-based FE. (A) Sagittal localizer image of the distal right tibia. The rectangle encompasses the area from which the transaxial high-resolution image data in B were collected. (B) The high-resolution cross-sectional image through the tibia, perpendicular to the vertical axis of the image in A, showing the trabecular architecture of the tibial metaphysis. The circle marks the virtual bone biopsy core. The rectangular VOI indicates the region for which μFE analysis was performed. X1, X2, and X3 represent the image coordinate system (with X3 representing the direction perpendicular to the display plane); x1, x2, and x3 represent the new material principal coordinate system calculated from FE analysis. (C) Cylindrical virtual bone biopsy core with the cubic VOI in the center. (D) μFE mesh for the cubic VOI.

VOI images were processed to construct μFE models by converting the image voxels representing bone to eight-node brick elements. The bone tissue material properties were chosen as isotropic, linearly elastic with a Young's modulus of 15 GPa, and a Poisson's ratio of 0.3 for all models. Using an element-by-element preconditioned conjugate gradient solver, six analyses were performed for each image, representing three uniaxial compression tests and three uniaxial shear tests.(17,34) The anisotropic stiffness tensor of each VOI was calculated in the original image coordinate system (X1, X2, and X3). Subsequently, the best-fit orthotropic stiffness matrix and the principal directions of the stiffness matrix were calculated by minimizing off-diagonal terms, and the compliance matrix was transformed to the new principal coordinate system (x1, x2, and x3; Fig. 1,(17) whereas x3 was always in the longitudinal direction of the tibia). Based on the compliance matrix, estimated elastic material constants (three Young's moduli, E11, E22, E33, and three shear moduli, G23, G31, G12) were calculated. The estimated elastic material constants were sorted such that E11 represented the smallest modulus and E33 the largest (E33 > E22 > E11).

ITS-based morphological analysis was performed.(32) Digital topological analysis (DTA)(35–40) combined with a volumetric reconstruction was used to segment trabecular bone microstructure into individual trabecular plates and rods.(30,32) A series of ITS-based morphological parameters of trabecular bone microstructure were calculated,(32) including plate bone volume fraction (pBV/TV), rod bone volume fraction (rBV/TV), trabecular plate and rod number density (pTb.N and rTb.N, 1/mm), mean trabecular plate thickness (pTb.Th, mm), mean trabecular rod thickness (rTb.Th, mm), mean trabecular plate surface area (pTb.S, mm2), and mean trabecular rod length (rTb.ℓ, mm).

Standard model-independent morphological analyses were also performed using a commercial software package (SCANCO Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). These included bone volume fraction (BV/TV), surface-to-volume ratio (BS/BV), mean trabecular number (Tb.N*, 1/mm), mean trabecular thickness (Tb.Th*, mm), mean trabecular separation (Tb.Sp*, mm), and connectivity density (Conn.D, 1/mm3). The geometrical degree of anisotropy (DA) and structure model index (SMI) were also calculated. The SMI is a parameter expressing the plate-likeness of the structure, with 0 for an ideal plate and 3 for an ideal rod structure.(29) DA was defined as the ratio between the maximal and minimal axes of the mean intercept length (MIL) ellipsoid.

Paired Student's t-tests were performed to evaluate differences between patient groups and to evaluate temporal changes from the baseline to 6, 12, and 24 mo after treatment, with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

RESULTS

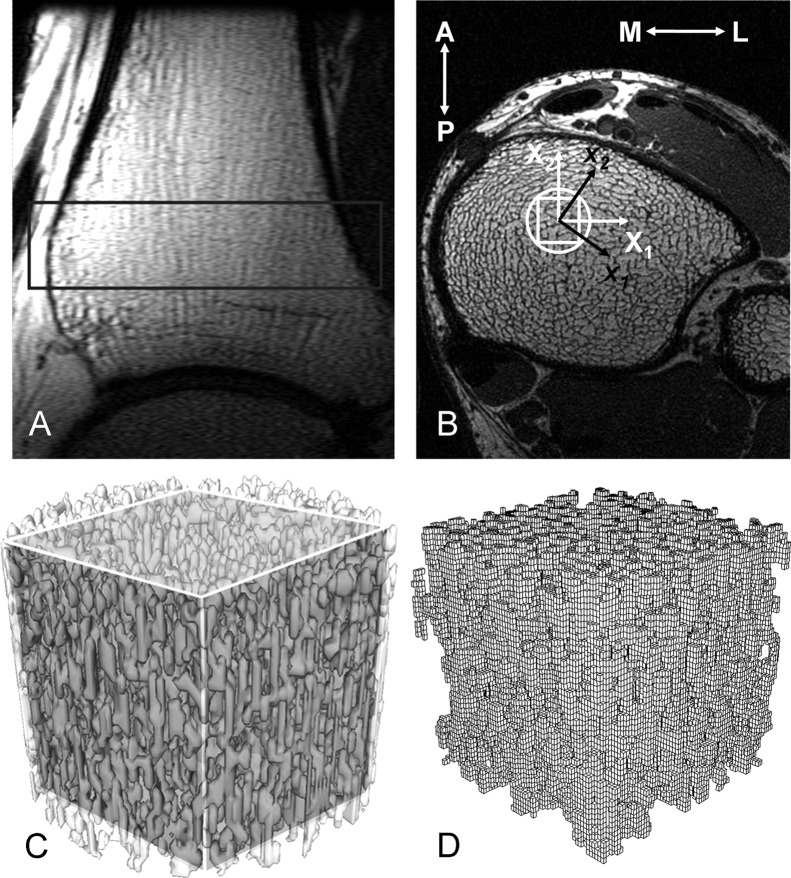

The estimated elastic moduli (E11, E33, G31, and G12) in the hypogonadal men were found to be significantly lower than those in the eugonadal controls (Table 1; Fig. 2A). In the worst cases, the estimated elastic moduli E11 and G31 were only 77% and 74% of that of eugonadal men, respectively. In the longitudinal assessments of estimated elastic moduli, there was no change in any parameter in the eugonadal group over 24 mo as expected (Fig. 2A). In contrast, several estimated elastic moduli (E22, E33, G23, and G12) increased after 24 mo of hormone replacement treatments, but no changes were detected at earlier time points of treatment (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that the four estimated elastic moduli (E22, E33, G23, and G12) within the hypogonadal group that significantly increased were the moduli that had relatively smaller differences compared with those of eugonadal group before the treatment; no significant changes were detected for the other two estimated moduli, E11 and G31, although these two estimated moduli of the hypogonadal group had an initial deficit of 23% or greater relative to the eugonadal group (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Anisotropic Elastic Moduli of Tibial Trabecular Bone at 0, 6, 12, and 24 mo for Eugonadal and Hypogonadal Groups

| 0 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 24 mo | ||

| Eugonadal | E11(GPa) | 0.557 (0.091) | 0.559 (0.099) | 0.528 (0.100) | 0.540 (0.104) |

| E22(GPa) | 0.783 (0.113) | 0.816 (0.106) | 0.764 (0.108) | 0.815 (0.109) | |

| E33(GPa) | 2.30 (0.21) | 2.30 (0.26) | 2.24 (0.24) | 2.24 (0.28) | |

| G23(GPa) | 0.512 (0.049) | 0.520 (0.049) | 0.495 (0.055) | 0.515 (0.061) | |

| G31(GPa) | 0.402 (0.059) | 0.402 (0.067) | 0.384 (0.061) | 0.390 (0.068) | |

| G12(GPa) | 0.257 (0.035) | 0.257 (0.040) | 0.245 (0.040) | 0.259 (0.040) | |

| Hypogonadal | E11(GPa) | 0.428 (0.049)* | 0.422 (0.044)* | 0.411 (0.051)* | 0.458 (0.040)* |

| E22(GPa) | 0.783 (0.066) | 0.802 (0.060) | 0.798 (0.073) | 0.851 (0.059)† | |

| E33(GPa) | 1.90 (0.13)* | 1.93 (0.10)* | 1.92 (0.13)* | 2.00 (0.11)*† | |

| G23(GPa) | 0.466 (0.042) | 0.476 (0.029)* | 0.475 (0.034) | 0.498 (0.031)† | |

| G31(GPa) | 0.298 (0.031)* | 0.295 (0.026)* | 0.288 (0.032)* | 0.313 (0.026)* | |

| G12(GPa) | 0.199 (0.023)* | 0.201 (0.022)* | 0.197 (0.024)* | 0.217 (0.022)*† |

Values are mean (SE), in GPa.

* Significant differences (p < 0.05; paired Student's t-test) between the eugonadal group and the hypogonadal group at the corresponding time point.

† Significant differences (p < 0.05; paired Student's t-test) between 0 mo and the following time points.

FIG. 2.

(A) Normalized elastic moduli of both hypogonadal and eugonadal groups (normalized by the corresponding modulus in the eugonadal group at baseline). (B) Relative changes in elastic moduli of the hypogonadal group from baseline at 6, 12, and 24 mo of treatment. Values shown are means ± SE. # p < 0.05 and *p < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared with the baseline.

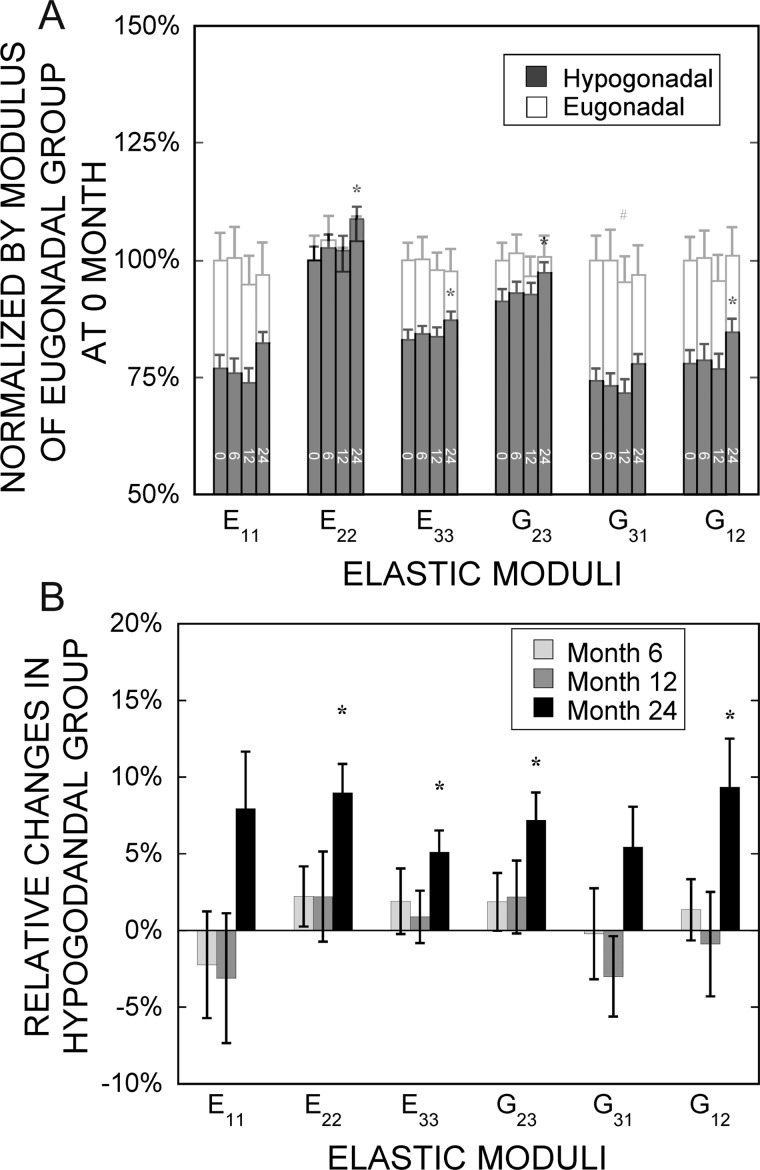

The ITS-based morphological analyses showed, in general, that tibial trabecular bone in hypogonadal men had significantly lower plate bone volume fraction (pBV/TV), mean trabecular plate thickness (pTb.Th), mean trabecular rod thickness (rTb.Th), and mean trabecular plate surface area (pTb.S) but significantly higher trabecular rod number (rTb.N) than those of eugonadal men at baseline (Table 2). These differences except rTb.N persisted throughout the 24 mo. There was no change in any of the ITS-based morphological parameters in the eugonadal group over 24 mo. In the hypogonadal group, however, a significant increase in pBV/TV was observed at 24 mo, whereas transient but significant decreases in rBV/TV and rTb.N were observed at 12 mo but not at 24 mo (Fig. 3). In addition, significant increases in pTb.Th (beginning at 12 mo), rTb.Th (at 24 mo), and pTb.S (beginning at 6 mo) were noticed.

Table 2.

Means and SEs for the ITS-Based Morphological Parameters After 0, 6, 12, and 24 mo for Eugonadal and Hypogonadal Groups

| 0 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 24 mo | ||

| Eugonadal | pBV/TV | 0.145 (0.007) | 0.150 (0.008) | 0.141 (0.006) | 0.140 (0.007) |

| rBV/TV | 0.124 (0.007) | 0.119 (0.007) | 0.125 (0.007) | 0.129 (0.006) | |

| pTb.N (mm−1) | 1.87 (0.01) | 1.87 (0.03) | 1.87 (0.02) | 1.87 (0.02) | |

| rTb.N (mm−1) | 1.97 (0.04) | 1.94 (0.05) | 1.97 (0.05) | 2.01 (0.04) | |

| pTb.Th (mm) | 0.161 (0.002) | 0.162 (0.002) | 0.159 (0.002) | 0.160 (0.002) | |

| rTb.Th (mm) | 0.181 (0.001) | 0.181 (0.001) | 0.181 (0.001) | 0.180 (0.001) | |

| pTb.S (mm2) | 0.136 (0.004) | 0.141 (0.004) | 0.134 (0.004) | 0.133 (0.004) | |

| rTb.ℓ (mm) | 0.574 (0.006) | 0.579 (0.005) | 0.574 (0.005) | 0.571 (0.004) | |

| Hypogonadal | pBV/TV | 0.109 (0.005)* | 0.115 (0.004)* | 0.115 (0.004)* | 0.118 (0.004)*† |

| rBV/TV | 0.143 (0.004) | 0.139 (0.004) | 0.138 (0.004)† | 0.140 (0.004) | |

| pTb.N (mm−1) | 1.85 (0.02) | 1.85 (0.01) | 1.85 (0.02) | 1.86 (0.02) | |

| rTb.N (mm−1) | 2.15 (0.03)* | 2.13 (0.02)* | 2.10 (0.02)† | 2.12 (0.02) | |

| pTb.Th (mm) | 0.148 (0.002)* | 0.150 (0.002)* | 0.150 (0.002)*† | 0.151 (0.001)*† | |

| rTb.Th (mm) | 0.174 (0.001)* | 0.174 (0.002)* | 0.176 (0.001)* | 0.176 (0.001)*† | |

| pTb.S (mm2) | 0.115 (0.002)* | 0.121 (0.002)*† | 0.120 (0.002)*† | 0.121 (0.002)*† | |

| rTb.ℓ (mm) | 0.561 (0.004) | 0.555 (0.003) | 0.567 (0.002) | 0.560 (0.003) |

* Significant differences (p < 0.05; paired Student's t-test) between the eugonadal group and the hypogonadal group at the corresponding time point.

† Significant differences (p < 0.05; paired Student's t-test) between 0 mo and the following time points.

FIG. 3.

Changes of ITS-based morphological parameters in the hypogonadal group after 6, 12, and 24 mo of treatment relative to the baseline. Values shown are means ± SE. # p < 0.05 and *p < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared with the baseline.

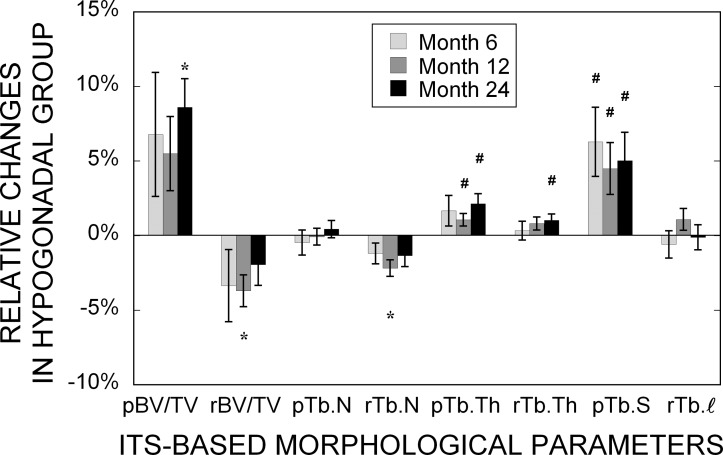

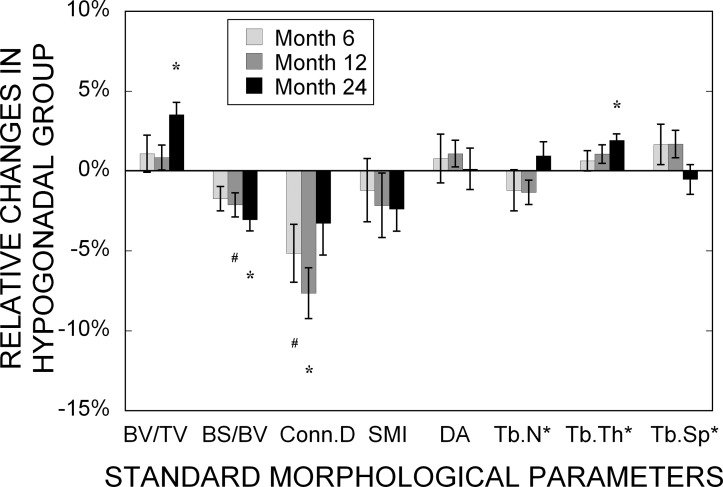

The standard morphological analyses, in general, showed that tibial trabecular bone in hypogonadal men had significantly lower bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and mean trabecular thickness (Tb.Th*) but significantly higher bone surface to volume ratio (BS/BV), connectivity density (Conn.D), and SMI than those of eugonadal men at baseline (Table 3). These differences also persisted throughout the 24-mo period of treatment. It is notable that there was no change in any of the morphological parameters in the eugonadal group over 24 mo. In the hypogonadal group, however, significant increases in BV/TV and Tb.Th* were observed at 24 mo, whereas a transient but significant decrease in Conn.D was observed at 6 and 12 mo but not at 24 mo (Fig. 4). In addition, a significant decrease in BS/BV at 12 and 24 mo was noticed.

Table 3.

Means and SEs for the Standard Morphological Parameters After 0, 6, 12, and 24 mo for Eugonadal and Hypogonadal Groups

| 0 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 24 mo | ||

| Eugonadal | BV/TV | 0.263 (0.004) | 0.263 (0.006) | 0.257 (0.006) | 0.261 (0.006) |

| BS/BV (mm−1) | 13.5 (0.2) | 13.3 (0.2) | 13.6 (0.2) | 13.5 (0.3) | |

| Conn.D (mm−3) | 5.84 (0.31) | 5.49 (0.32) | 5.66 (0.39) | 5.87 (0.32) | |

| SMI | 1.44 (0.05) | 1.39 (0.06) | 1.47 (0.05) | 1.45 (0.07) | |

| DA | 2.46 (0.03) | 2.50 (0.04) | 2.51 (0.02) | 2.45 (0.02) | |

| Tb.N* (mm−1) | 2.52 (0.06) | 2.50 (0.07) | 2.53 (0.07) | 2.55 (0.06) | |

| Tb.Th* (mm) | 0.170 (0.003) | 0.172 (0.003) | 0.168 (0.003) | 0.170 (0.002) | |

| Tb.Sp* (mm) | 0.408 (0.010) | 0.413 (0.012) | 0.408 (0.013) | 0.405 (0.010) | |

| Hypogonadal | BV/TV | 0.236 (0.004)* | 0.239 (0.004)* | 0.238 (0.004)* | 0.244 (0.004)† |

| BS/BV (mm−1) | 15.5 (0.3)* | 15.3 (0.3)* | 15.1 (0.3)*† | 15.0 (0.2)*† | |

| Conn.D (mm−3) | 7.38 (0.24)* | 7.13 (0.21)*† | 6.81 (0.24)† | 7.12 (0.20)* | |

| SMI | 1.67 (0.04)* | 1.64 (0.04)* | 1.64 (0.04) | 1.64 (0.05) | |

| DA | 2.54 (0.04) | 2.55 (0.03) | 2.57 (0.03) | 2.54 (0.04) | |

| Tb.N* (mm−1) | 2.65 (0.04) | 2.64 (0.05) | 2.62 (0.05) | 2.68 (0.04) | |

| Tb.Th* (mm) | 0.153 (0.001)* | 0.153 (0.002)* | 0.154 (0.002)* | 0.156 (0.002)*† | |

| Tb.Sp* (mm) | 0.382 (0.006) | 0.385 (0.008) | 0.389 (0.007) | 0.380 (0.007) |

* Significant differences (p < 0.05; paired Student's t-test) between the eugonadal group and the hypogonadal group at the corresponding time point.

† Significant differences (p < 0.05; paired Student's t-test) between 0 mo and the following time points.

FIG. 4.

Changes of standard morphological parameters in the hypogonadal group after 6, 12, and 24 mo of treatment relative to the baseline. Values shown are means ± SE. # p < 0.05 and *p < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared with the baseline.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed significant differences between eugonadal and hypogonadal men in four anisotropic elastic moduli computed by μFE analysis on the basis of in vivo μMR images of tibial trabecular bone. More importantly, significant increases in estimated elastic moduli E22, E33, G23, and G12 were found in hypogonadal men after 24 mo of treatment. These results are the first compelling demonstration of treatment effects of hormone replacement on trabecular bone mechanical constants derived from in vivo high-resolution μMRI data.

It is further noted that after 24 mo of treatment, the restoration in anisotropic elastic properties was not uniform among different principal directions. E11 and G31 had the highest initial deficits (>23%) before treatment in the hypogonadal group compared with those of eugonadal men (Fig. 2A). However, there was no significant increase in E11 and G31 after 24 mo of treatment. This observation might suggest that the effect of testosterone treatment on mechanical properties is anisotropic, in that the estimated elastic modulus of tibial trabecular bone with higher initial loss (E11, G31) in testosterone deficiency is less recoverable with treatment.

The preliminary validation study comparing high-resolution μCT and simulated μMR images indicated the estimated elastic moduli in substantially different resolution regimens to be highly correlated with one another (Appendix 1). Because predictions of elastic moduli from FE analysis based on μCT images are known to be accurate estimates of those determined experimentally, these data lend added credence to the mechanical constants derived from in vivo μMR images in patients undergoing treatment. In this study, the “simulated” μMR images were resampled in the Fourier domain (k-space) to a resolution corresponding to that achievable by in vivo μMRI. In addition, the simulated μMR images had a noise level and noise statistics equivalent to actual μMR images. The μCT images used for validation included specimens from anatomic sites such as the femur and spine. Whereas these preliminary validation results are encouraging, a more extensive evaluation will be needed to establish the method's clinical potential.

The results of this study emphasize the critical importance of microstructure of trabecular bone as a determinant of its mechanical competence. The deficit of bone volume fraction in these severely hypogonadal men relative to those in the eugonadal peers was found to be significant but relatively modest (7.7%). By contrast, the elastic moduli were lower by as much as 23% in some directions. These observations provide a further impetus toward the development and application of noninvasive in vivo microimaging techniques for quantifying trabecular bone microstructure as input to μFE analysis. The data also emphasize the potential importance of a more detailed analysis of the architectural changes such as they are amenable by the authors' ITS-based and standard morphological analysis techniques.

The ITS-based morphological analyses identified a significantly lower trabecular plate bone volume fraction (pBV/TV) and trabecular plate thickness (pTb.Th) in hypogonadal men compared with eugonadal men at baseline. Furthermore, the ITS-based morphological analyses yielded a significantly higher pBV/TV and pTb.Th after 24 mo of treatment in hypogonadal men, suggesting that testosterone treatment improved the tibial trabecular bone microstructure in hypogonadal men by a significant increase in trabecular plate thickness and trabecular plate bone volume fraction, which implies that the architecture became more “plate-like.” These observations are consistent with previous topological analysis but with greater specificity and quantification.(15) However, some caution is advised with respect to trabecular rod–related parameters (rBV/TV and rTb.N) as well as trabecular plate surface area (pTb.S) at the limited resolution of clinical μMRI (Appendix 1). Nevertheless, this study showed the plausibility of ITS-based analysis in clinical μMR images to estimate individual trabecular plate morphologies, which has been shown to be important in mechanical properties of trabecular bone.(30,32,41)

In a previous study of the same image data,(15) the surface-to-curve ratio (a topological representation of the ratio of trabecular plates to trabecular rods) was found to increase by 11.2% and the topological erosion index (a ratio of the sum of topological parameters expected to increase, divided by the sum of those expected to decrease as a result of excessive osteoclast resorption) decreased by 7.5% after 24 mo of testosterone treatment. The authors suggested that testosterone replacement of hypogonadal men may not only retard bone resorption but may reverse the deterioration of trabecular architecture because the increase in the surface-to-curve ratio suggests that treatment partially restores trabecular connectivity. These data provide further evidence in support of the previously observed effects indicating that the changes in the surface-to-curve ratio or topological erosion index are caused by an increase in plate volume.

The standard morphological analyses detected significant differences between the two groups at baseline in BV/TV, BS/BV, SMI, Conn.D, and Tb.Th*. In addition, improvements in BV/TV and Tb.Th* after 24 mo of treatment were found paralleling those of the ITS-based morphological parameters. Despite the limited resolution of clinical μMRI, the validation study further suggests that the standard 3D model-independent morphological analysis could provide robust estimates of in vivo trabecular microstructure comparable to those based on high resolution μCT images. There was no change in the SMI, which is the primary measure of trabecular type in the standard 3D morphological analysis. However, the topological surface-to-curve ratio, which has been found to be a sensitive measure of the bone's relative “plate-likeness,”(15) and the recently introduced ITS-based parameters, both indicated a transition to more plate-like trabecular microstructure at lower resolution. Therefore, both standard and ITS-based morphological analyses may be useful measures for evaluating in vivo trabecular bone microstructure from μMR images.

No significant changes were detected in terms of trabecular plate number or trabecular rod number after 24 mo of treatment. This is similar to many in vivo experimental studies using intermittent PTH or bisphosphonate administration, although the mechanisms of their actions are different.(42–44) In general, whereas these interventions yielded improvements in the bone's mechanical properties by increasing trabecular thickness, they did not affect trabecular number. The results of simulated erosion showed that loss of entire trabecular elements is more detrimental than an equal amount of bone loss by uniform thinning of trabeculae.(45) Therefore, the timing of treatment has been recognized as important in the management of osteoporosis.

There are several limitations in this study. The study is inherently limited by the tibial trabecular bone site where osteoporotic fractures are rare. High-resolution imaging techniques have been limited thus far to peripheral bone sites such as the distal tibia and radius or the calcaneus.(16,20,40) Nevertheless, the results from this study in hypogonadal men indicating detectable changes in both structural and mechanical parameters in response to treatment support the use of the tibial site as a surrogate location for assessing bone. The second limitation is that only linear analysis for elastic moduli has been performed in this study even though nonlinear analysis for trabecular bone strength is now possible. The challenges for nonlinear analysis are how in vivo mechanical loading conditions can be determined and implemented in computations of small subvolumes of tibial trabecular bone. On the other hand, there is ample evidence for the high degree of correlation between strength and elastic modulus of trabecular bone.(23,46–48) The accuracy and precision of FE analysis, new ITS-based morphological analysis, and the standard morphological parameters have been studied in a preliminary validation study (Appendix 1). These data are encouraging and support applications of these techniques in clinical μMRI of patients with metabolic bone disease. The validation study was performed with simulated MR images, whereas further studies including both simulated and real MR images to evaluate the use of the described approaches are in progress. The third limitation is that constant bone tissue property has been assumed for all FE models. Although it is known that bone strength and fracture risk is a function of microstructures, bone tissue composition, and other factors, there is little evidence that osteoporotic bone is fundamentally different from normal bone in its intrinsic properties. Unlike μCT-based FE models that could make use of density differences based on variations in the measured X-ray attenuation of bone mineral, such information is not amenable from μMRI, which images bone marrow and infers the presence and location of bone indirectly. Last, the analyses were performed in small subvolumes of available μMR images, which provide limited information on whole bone mechanical behavior. Therefore, extension of mechanical structural analysis (i.e., determination of the structural stiffness and strength) to the entire section of the distal tibia will be of particular interest. However, the trade-off between additional parameters for mechanical competence and the large computational cost and time will have to be determined for clinical usefulness.

In summary, image-based μFE analysis and the new ITS-based and the standard morphological analyses were applied to study the anisotropic elastic and morphological properties of eugonadal and hypogonadal men before and after treatment. Differences in estimated elastic moduli and morphological parameters were detected between the eugonadal and hypogonadal groups, and improvements were found on treatment in the hypogonadal group. With the increasing availability of high-resolution in vivo μMRI and μCT imaging for clinical assessment of osteoporosis, image-based μFE modeling and ITS-based and standard morphological analyses are likely to provide new insight for detection, management, and treatment of patients with bone disease in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by grants from NIH (R01 AR053156, R01 AR051376, R21 AR049613, R01 AR055647, and M01-RR00041).

APPENDIX 1: VALIDATION STUDY OF μMRI-BASED ANALYSES

To address the impact of clinical resolution of μMRI on the estimated mechanical and morphological properties, 13 cylindrical trabecular samples (diameter, 5.20 mm; length, 30 mm) were obtained from two third lumbar vertebrae (52- and 50-yr-old men), four proximal femurs (one pair: 60-yr-old woman, two singles: 64- and 44-yr-old men), and one pair of proximal tibiae (69-yr-old man) according to previously established protocol(47,49–51) and scanned by μCT (VivaCT 40; Scanco Medical) at 21 × 21 × 22-μm resolution. The images were binarized by setting a threshold at the midpoint of the two modes of the histogram and downsampled in the spatial frequency domain (k-space) by a factor of 6 × 6 × 18, yielding anisotropic resolution ∼126 × 126 × 396 μm. Subsequently, gaussian noise was added to real and imaginary parts of the downsampled data sets, and the absolute values were computed to convert gaussian noise to rician noise,(52) resulting in a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 14. The downsampled images were comparable in terms of resolution and SNR to those obtained by in vivo virtual bone biopsy (VBB).(53) These simulated, partial volume blurred μMR images were subvoxel-processed analogous to the in vivo images. Both original high-resolution μCT images and the corresponding simulated μMR images were subsequently subjected to FE analysis and ITS-based and standard morphological analyses, as described earlier. Linear regressions were performed between the estimated elastic moduli and morphological parameters of high-resolution μCT images and those of the corresponding simulated μMR images. A full account of these studies examining the effect of resolution and noise on trabecular bone mechanical parameters will be given elsewhere.

The comparisons of the estimated elastic moduli between high-resolution μCT and the corresponding simulated μMR images indicated excellent correlations (r 2 = 0.981–0.997):

The validation results of ITS-based morphological parameters indicated that trabecular plate associated parameters of the low-resolution, simulated μMR images were significantly correlated with those derived directly from the high-resolution μCT images (except pTb.S). Trabecular rod associated parameters from simulated μMRI, in general, correlated poorly with those from μCT, except rBV/TV and rTb.N. These results were consistent with the fact that simulated in vivo μMR images make the estimation of trabecular rod related parameters difficult.

On the other hand, it was interesting to observe that the standard 3D morphological parameters, in general, showed excellent correlations between those from simulated μMR images and those from μCT images.

Footnotes

Dr Wehrli is Chairman of the Scientific Advisory Board, owns stock in, and holds patents licensed to MicroMRI. Drs Guo and Liu have a pending patent of invention. All other authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Melton LJ., III . Epidemiology of fractures. In: Riggs BL, Melton LJ III, editors. Osteoporosis: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Management. New York, NY, USA: Raven Press; 1988. pp. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Consensus development conference: Prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1991;1:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright VJ. Osteoporosis in Men. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:347–353. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200606000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein JS, Klibanski A, Neer RM, Doppelt SH, Rosenthal DI, Segre GV, Crowley WF., Jr Increases in bone density during treatment of men with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;69:776–783. doi: 10.1210/jcem-69-4-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katznelson L, Finkelstein JS, Schoenfeld DA, Rosenthal DI, Anderson EJ, Klibanski A. Increase in bone density and lean body mass during testosterone administration in men with acquired hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4358–4365. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.12.8954042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behre HM, Kliesch S, Leifke E, Link TM, Nieschlag E. Long-term effect of testosterone therapy on bone mineral density in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2386–2390. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Berlin JA, Hannoush P, Haddad G, Dlewati A, Santanna J, Loh L, Lenrow DA, Holmes JH, Kapoor SC, Atkinson LE, Strom BL. Effects of testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2670–2677. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melton LJ., III Epidemiology of hip fractures: Implications of the exponential increase with age. Bone. 1996;18:121–125. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stokstad E. Bone quality fills holes in fracture risk. Science. 2005;308:1580. doi: 10.1126/science.308.5728.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller R, Hildebrand T, Ruegsegger P. Non-invasive bone biopsy: A new method to analyse and display the three-dimensional structure of trabecular bone. Phys Med Biol. 1994;39:145–164. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/39/1/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majumdar S, Genant HK. A review of the recent advances in magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1995;5:79–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01623308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laib A, Ruegsegger P. Calibration of trabecular bone structure measurements of in vivo three-dimensional peripheral quantitative computed tomography with 28-μm-resolution microcomputed tomography. Bone. 1999;24:35–39. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hildebrand T, Laib A, Muller R, Dequeker J, Ruegsegger P. Direct three-dimensional morphometric analysis of human cancellous bone: Microstructural data from spine, femur, iliac crest, and calcaneus. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1167–1174. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benito M, Gomberg B, Wehrli FW, Weening RH, Zemel B, Wright AC, Song HK, Cucchiara A, Snyder PJ. Deterioration of trabecular architecture in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1497–1502. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benito M, Vasilic B, Wehrli FW, Bunker B, Wald M, Gomberg B, Wright AC, Zemel B, Cucchiara A, Snyder PJ. Effect of testosterone replacement on trabecular architecture in hypogonadal men. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1785–1791. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutroy S, Bouxsein ML, Munoz F, Delmas PD. In vivo assessment of trabecular bone microarchitecture by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6508–6515. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Rietbergen B, Odgaard A, Kabel J, Huiskes R. Direct mechanics assessment of elastic symmetries and properties of trabecular bone architecture. J Biomech. 1996;29:1653–1657. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Rietbergen B, Majumdar S, Pistoia W, Newitt DC, Kothari M, Laib A, Ruegsegger P. Assessment of cancellous bone mechanical properties from micro-FE models based on micro-CT, pQCT and MR images. Technol Health Care. 1998;6:413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newitt DC, van Rietbergen B, Majumdar S. Processing and analysis of in vivo high-resolution MR images of trabecular bone for longitudinal studies: Reproducibility of structural measures and micro-finite element analysis derived mechanical properties. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:278–287. doi: 10.1007/s001980200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Rietbergen B, Majumdar S, Newitt D, MacDonald B. High-resolution MRI and micro-FE for the evaluation of changes in bone mechanical properties during longitudinal clinical trials: Application to calcaneal bone in postmenopausal women after one year of idoxifene treatment. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2002;17:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pistoia W, van Rietbergen B, Lochmuller EM, Lill CA, Eckstein F, Ruegsegger P. Estimation of distal radius failure load with micro-finite element analysis models based on three-dimensional peripheral quantitative computed tomography images. Bone. 2002;30:842–848. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pistoia W, van Rietbergen B, Lochmuller EM, Lill CA, Eckstein F, Ruegsegger P. Image-based micro-finite-element modeling for improved distal radius strength diagnosis: Moving from bench to bedside. J Clin Densitom. 2004;7:153–160. doi: 10.1385/jcd:7:2:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niebur GL, Feldstein MJ, Yuen JC, Chen TJ, Keaveny TM. High-resolution finite element models with tissue strength asymmetry accurately predict failure of trabecular bone. J Biomech. 2000;33:1575–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niebur GL, Yuen JC, Burghardt AJ, Keaveny TM. Sensitivity of damage predictions to tissue level yield properties and apparent loading conditions. J Biomech. 2001;34:699–706. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niebur GL, Feldstein MJ, Keaveny TM. Biaxial failure behavior of bovine tibial trabecular bone. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124:699–705. doi: 10.1115/1.1517566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bevill G, Eswaran SK, Gupta A, Papadopoulos P, Keaveny TM. Influence of bone volume fraction and architecture on computed large-deformation failure mechanisms in human trabecular bone. Bone. 2006;39:1218–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim CH, Zhang XH, Mikhail G, von Stechow D, Muller R, Kim HS, Guo XE. Effects of thresholding techniques on microCT-based finite element models of trabecular bone. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129:481–486. doi: 10.1115/1.2746368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hildebrand T, Ruegsegger P. A new method for the model-independent assessment of thickness in three-dimensional images. J Microsc. 1997;185:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hildebrand T, Ruegsegger P. Quantification of bone microarchitecture with the structure model index. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 1997;1:15–23. doi: 10.1080/01495739708936692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu XS, Sajda P, Saha PK, Wehrli FW, Guo XE. Quantification of the roles of trabecular microarchitecture and trabecular type in determining the elastic modulus of human trabecular bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1608–1617. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stauber M, Muller R. Volumetric spatial decomposition of trabecular bone into rods and plates–a new method for local bone morphometry. Bone. 2006;38:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu XS, Sajda P, Saha PK, Wehrli FW, Bevill G, Keaveny TM, Guo XE. Complete volumetric decomposition of individual trabecular plates and rods and its morphological correlations with anisotropic elastic moduli in human trabecular bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:223–235. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.071009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang SN, Wehrli FW. Subvoxel processing: A method for reducing partial volume blurring with application to in vivo MR images of trabecular bone. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:948–957. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollister SJ, Brennan JM, Kikuchi N. A homogenization sampling procedure for calculating trabecular bone effective stiffness and tissue level stress. J Biomech. 1994;27:433–444. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha PK, Chaudhuri BB. Detection of 3-D simple points for topology preserving. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1994;16:1028–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha PK, Chaudhuri BB. 3D Digital topology under binary transformation with applications. Comput Vis Image Underst. 1996;63:418–429. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saha PK, Chaudhuri BB, Majumder DD. A new shape preserving parallel thinning algorithm for 3D digital images. Pattern Recog. 1997;30:1939–1955. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saha PK, Gomberg BR, Wehrli FW. Three-dimensional digital topological characterization of cancellous bone architecture. Int J Imaging Syst Technol. 2000;11:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomberg BR, Saha PK, Song HK, Hwang SN, Wehrli FW. Topological analysis of trabecular bone MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2000;19:166–174. doi: 10.1109/42.845175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wehrli FW, Gomberg BR, Saha PK, Song HK, Hwang SN, Snyder PJ. Digital topological analysis of in vivo magnetic resonance microimages of trabecular bone reveals structural implications of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1520–1531. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stauber M, Rapillard L, van Lenthe GH, Zysset P, Muller R. Importance of individual rods and plates in the assessment of bone quality and their contribution to bone stiffness. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:586–595. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li M, Mosekilde L, Sogaard CH, Thomsen JS, Wronski TJ. Parathyroid hormone monotherapy and cotherapy with antiresorptive agents restore vertebral bone mass and strength in aged ovariectomized rats. Bone. 1995;16:629–635. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00115-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okimoto N, Tsurukami H, Okazaki Y, Nishida S, Sakai A, Ohnishi H, Hori M, Yasukawa K, Nakamura T. Effects of a weekly injection of human parathyroid hormone (1-34) and withdrawal on bone mass, strength, and turnover in mature ovariectomized rats. Bone. 1998;22:523–531. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohnishi H, Nakamura T, Narusawa K, Murakami H, Abe M, Barbier A, Suzuki K. Bisphosphonate tiludronate increases bone strength by improving mass and structure in established osteopenia after ovariectomy in rats. Bone. 1997;21:335–343. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo XE, Kim CH. Mechanical consequence of trabecular bone loss and its treatment: A three-dimensional model simulation. Bone. 2002;30:404–411. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keaveny TM, Wachtel EF, Ford CM, Hayes WC. Differences between the tensile and compressive strengths of bovine tibial trabecular bone depend on modulus. J Biomech. 1994;27:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morgan EF, Keaveny TM. Dependence of yield strain of human trabecular bone on anatomic site. J Biomech. 2001;34:569–577. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeni YN, Dong XN, Fyhrie DP, Les CM. The dependence between the strength and stiffness of cancellous and cortical bone tissue for tension and compression: Extension of a unifying principle. Biomed Mater Eng. 2004;14:303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keaveny TM, Guo XE, Wachtel EF, McMahon TA, Hayes WC. Trabecular bone exhibits fully linear elastic behavior and yields at low strains. J Biomech. 1994;27:1127–1136. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kopperdahl DL, Keaveny TM. Yield strain behavior of trabecular bone. J Biomech. 1998;31:601–608. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang WC, Christensen TM, Pinilla TP, Keaveny TM. Uniaxial yield strains for bovine trabecular bone are isotropic and asymmetric. J Orthop Res. 1999;17:582–585. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gudbjartsson H, Patz S. The Rician distribution of noisy MRI data. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:910–914. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wehrli FW, Saha PK, Gomberg BR, Song HK. Noninvasive assessment of bone architecture by magnetic resonance micro-imaging-based virtual bone biopsy. Proc IEEE. 2003;91:1520–1542. [Google Scholar]