Abstract

Targeted disruption of the dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) gene in the mice (Dspp−/−) results in dentin mineralization defects with enlarged predentin phenotype similar to human dentinogenesis imperfecta type III. Using DSPP/biglycan (Dspp−/−Bgn−/0) and DSPP/decorin (Dspp−/−Dcn−/−) double knockout mice, here we determined that the enlarged predentin layer in Dspp−/− is rescued in the absence of decorin, but not in the absence of biglycan. However, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis reveals similar hypomineralization of dentin in both Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− teeth. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis of collagen fibrils in dentin shows subtle differences in the collagen fibril morphology of these genotypes. The reduction of enlarged predentin in Dspp−/−Dcn−/− suggests that the elevated level of decorin in Dspp−/− predentin interferes with the mineralization process at the dentin mineralization front. On the other hand, the lack of DSPP and biglycan leads to the increased number of calcospherites in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 predentin, suggesting that a failure in coalescence of calcospherites was augmented in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 as compared to Dspp−/− teeth. These findings indicate that normal expression of small leucine rich proteoglycans, such as biglycan and decorin, plays an important role in the highly orchestrated process of dentin mineralization.

Keywords: dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP), biglycan, decorin, knockout mouse, dentin mineralization, and dentinogenesis imperfecta (DGI)

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, significant progress has been made to further our understanding of non-collagenous proteins in dentin matrix. Indeed, dentin contains relatively unique non-collagenous extracellular matrix proteins, such as members of the SIBLING (small integrin-binding ligand glycoprotein) (Fisher et al., 2003) and SLRPs (small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycans) families (Iozzo, 1997). These proteins are mainly secreted by odontoblasts (Embery et al., 2001). The SIBLING family of secreted glycophosphoproteins includes bone sialoprotein (BSP), dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP1), osteopontin (OPN), matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE), and dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) (Fisher et al., 2003; Fisher et al., 2001).

DSPP, a highly acidic phosphorylated protein, is the major non-collagenous ECM in dentin. The Dspp gene, harboring five exons, is located among the SIBLING gene family cluster on mouse chromosome 5 (human chromosome 4) (Feng et al., 1998; MacDougall, 2003; MacDougall et al., 2006; Qin et al., 2004). The DSPP protein, encoded from 4.4 kb mRNA, is believed to be cleaved into dentin sialoprotein (DSP) and dentin phosphoprotein (DPP; also known as phosphophoryn) (MacDougall et al., 1997). A third portion of cleaved proteins, dentin glycoprotein (DGP), has been recently identified in the pig (Yamakoshi et al., 2005). The targeted disruption of the Dspp gene in mice (Dspp−/− mouse) showed a tooth phenotype similar to that observed in dentinogenesis imperfecta type III (DGI-III) patients (OMIM#125500), including enlarged pulp chambers, increased width of predentin and dentin hypomineralization (Sreenath et al., 2003). However, the precise roles of DSP and DPP are not fully understood. We earlier found that the Dspp−/− mouse had an increased deposition of two SLRPs, biglycan (BGN) and decorin (DCN), in the predentin zone, suggesting that the increased levels of biglycan or decorin may be the cause or consequence of hypomineralization and widened predentin in Dspp−/− mice (Sreenath et al., 2003).

The members of the SLRP family have core proteins of about 40 kDa, that are dominated by a central domain composed of 6–10 tandemly repeated leucine rich sequences, and characteristics N- and C-terminal domains (Iozzo, 1999). Recent analysis of SLRP family encompasses now 5 classes with 17 distinct genes involved in a variety of cellular functions and signaling (Schaefer et al., 2008). Biglycan (Fisher et al., 1989) and decorin (Krusius et al., 1986) are the closest members of class I SLRPs. Biglycan and decorin are widely distributed in mammalian tissues, including mineralized tissues such as bone and teeth (Hocking et al., 1998; Iozzo et al., 1996; Reed et al., 2002). The N-terminal regions of decorin and biglycan are substituted with one and two chondroitin-sulfate (CS)/dermatan-sulfate (DS) glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) chains, respectively (Embery et al., 2001). The SLRPs, especially decorin, appear to interact with collagen through the binding with the leucine rich region of the protein core (Weber et al., 1996), which can modify the deposition and arrangement of collagen fibrils in the ECMs of soft tissues (Danielson et al., 1997). In addition to modifying the extracellular environment, interactions of SLRPs with cells, and with growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) affect the proliferation of cells (Ferdous et al., 2007; Kresse et al., 2001; Markmann et al., 2000).

To delineate the precise functions of biglycan and decorin in dentin defects observed in Dspp−/− mice, we generated and analyzed DSPP/biglycan and DSPP/Decorin double knock out (KO) mice (Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/−). Our findings here show that the elevated decorin expression is one of the major causative factors of the enlarged predentin phenotype in Dspp−/− mouse teeth.

2. Results

2.1. Biglycan and decorin expression in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 or Dspp−/−Dcn−/− mouse incisors

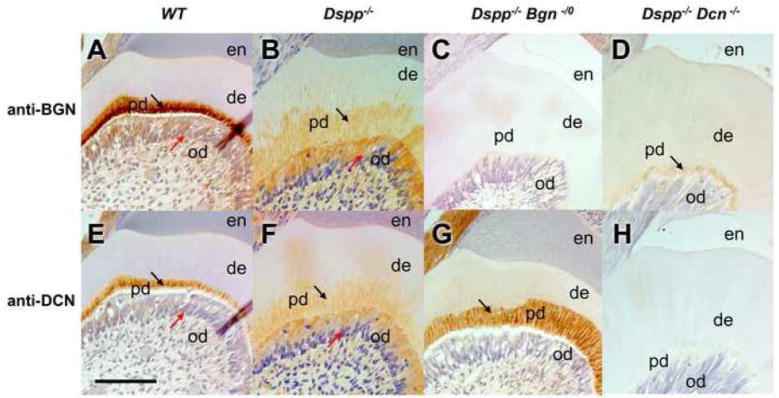

After the serial mating of progeny from Dspp−/− x Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/− x Dcn−/−, the successful generation of Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 or Dspp−/−Dcn−/− mice was confirmed by genotyping using PCR (data not shown), and also by immunostaining of tooth sections using anti-BGN or anti-DCN specific antibodies (Fig. 1). No positive staining for biglycan or decorin could be detected in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 or Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisors, respectively (Fig. 1 C and H). In WT incisors, biglycan and decorin were predominantly distributed in a thin predentin layer (Fig. 1 A and E; black arrows) and odontoblasts (Fig. 1 A and E; red arrows). The biglycan and decorin were also localized in Dspp−/− widened predentin (Fig. 1 B and F; black arrows) and in odontoblasts (Fig. 1 B and F; red arrows) as previously reported (Sreenath et al., 2003). The biglycan and decorin staining was barely visible in the mineralized dentin region of all the genotypes. Notably, the widened predentin zone in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 exhibited a strong immunostaining for decorin (Fig. 1G, arrow). The Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisor showed biglycan staining in the thin predentin layer (Fig. 1D, arrow).

Fig. 1. Localization of biglycan and decorin in WT, Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/−, and Dspp−/− Dcn−/− mice.

Immunostaining of 6-month-old incisors from WT, Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/−, and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− mice with anti-BGN or anti-DCN antibodies. In WT, biglycan and decorin were predominantly distributed in the narrow predentin (A and D; black arrows) and odontoblast cell bodies (A and D; read arrows). The biglycan and decorin were also localized in Dspp−/− widened predentin (Fig. 1 B and F; black arrows) and in odontoblasts (Fig. 1 B and F; red arrows) as previously reported. Biglycan or decorin could not be detected in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 (C) or Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisor teeth (H), respectively. en, enamel; de, dentin; pd, predentin; od, odontoblasts. Bar = 100 μm

2.2. Decorin deficiency in the Dspp−/− mice rescues the widened-predentin phenotype, while biglycan deficiency displays an increased number of calcospherites at the mineralization front in the Dspp−/− mice

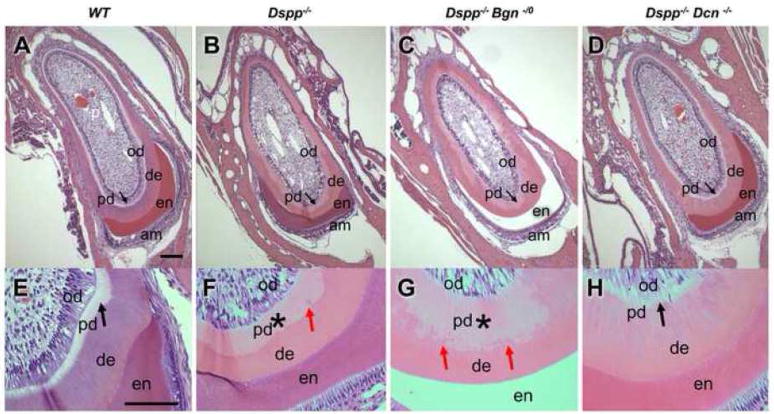

Histological analysis of WT, Dspp −/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisors was performed by H&E staining (Fig. 2). The dentin in Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisors was eosinophilic, whereas the WT incisor showed hematoxyphil dentin with a more intense purple color. In the WT incisor, the thick dentin and thin predentin (black arrows), lined by an odontoblast layer, surrounded the tooth pulp (Fig. 2A and E). As previously reported, Dspp−/− mice showed increased width of predentin with pale pink color (Fig. 2B and 2F, asterisk). The predentin in Dspp−/− mice displayed an increased number of calcospherites (globular dentin) formed at the mineralization front, as compared to WT (Fig. 2F, red arrows). In the Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 incisor, the predentin width remained widened with a concurrent increase in the number of calcospherites, resulting in the irregular mineralization front (Fig. 2C and G, asterisk and red arrows). However, the lack of decorin in the DSPP null background significantly rescued the widened predentin phenotype observed in the Dspp−/− incisor (Fig. 1 D and H, black arrows).

Fig. 2. Widened predentin resembling dentinogenesis imperfecta in Dspp−/− null mice was reduced in thickness by removing decorin.

H&E stainings of 6-month-old incisors from WT (A and E), Dspp−/−(B and F), Dspp−/−Bgn−/−(C and G) and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− (D andH) mice. The thick dentin and thin predentin (A and E; black arrow), lined by an odontoblast layer, surrounded the pulp in the WT incisor. Widened predentin was clearly observed in Dspp−/− mouse (B; arrow and F; *). Biglycan deletion did not alter the widened predentin phenotype in Dspp−/− mouse (C; arrow and G; *). The number of calcospherites was increased, thus forming an irregular mineralization front (G; red arrows). Most notably, decorin deletion restored widened predentin phenotype in Dspp−/− teeth (D and H; black arrows). am, ameloblasts; en, enamel; de, dentin; pd, predentin; od, odontoblasts. Bars = 100 μm

2.3. Dentin hypomineralization in Dspp−/− mice remains unchanged by the deficiency of decorin or biglycan

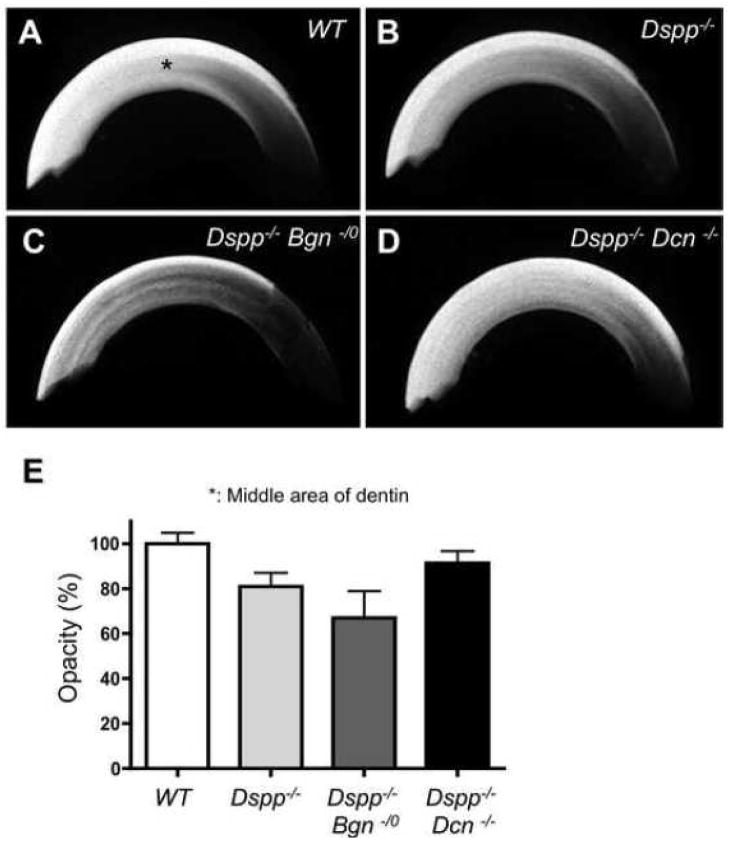

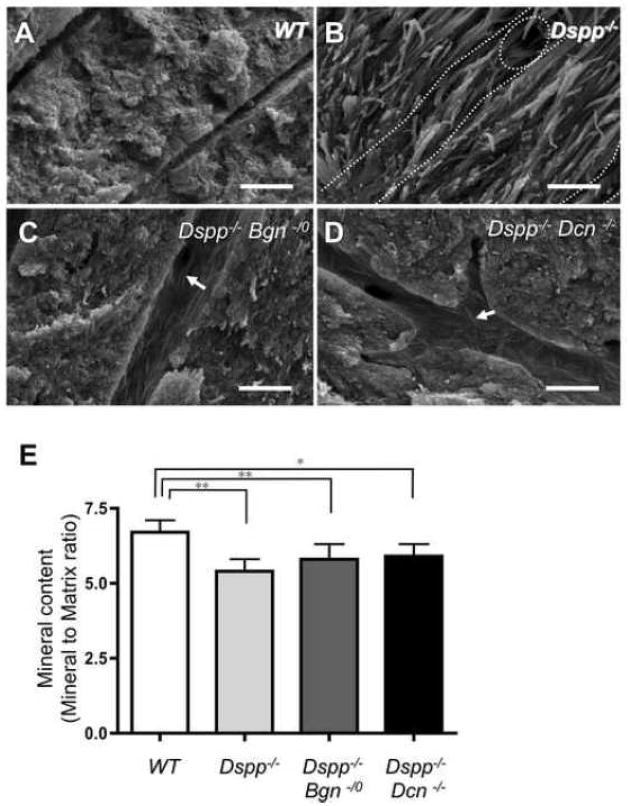

To compare the differences in dentin mineralization among the four different genotypes, the incisors were examined by microradiography (Fig. 3). The X-ray opacities of dentin at the labiolingual middle area (pointed in Fig. 3A, asterisk) appeared to be decreased in Dspp−/− mice (Fig. 3B), as compared to X-ray opacities in WT mice. The opacity in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 incisor looked strikingly decreased (Fig. 3C), whereas the Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisor demonstrated the increased opacity (Fig. 3D) as compared with the Dspp−/− incisor (representative graph shown in Fig. 3E). To further analyze and compare the differences in mineralization at the ultra-structural level, the incisors were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 4A–D). The fractured surface characteristics of the WT incisor indicated a compact and mineralized dentin. Compared to the WT incisors, the collagen fibrils were clearly seen in the fractured dentin surface of the Dspp−/− incisors (Fig. 4A and B). Collagen fibrils were also observed in the dentinal tubles and intertubular dentin of Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisors (Fig. 4C and D), but there were far fewer than the amount seen in Dspp−/− incisors. Quantitative analysis by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was also performed to compare the mineral contents (mineral to matrix ratio) in dentin (Fig. 4E). The Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− mice had significantly lower mineral contents in dentin as compared to those in WT mice. The Dspp−/− dentin had the lowest mineral contents among the three knockout mice groups. The mean values of mineral content in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− were larger than those in the Dspp−/−, but not statistically significant.

Fig. 3. Altered X-ray opacity in upper incisors examined by microradiography.

(A–D) Microradiographies taken from WT (A), Dspp−/−(B), Dspp−/−Bgn−/−(C) and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− (D) mice. The X-ray opacities in the labiolingually middle area of the incisors (*) were compared for mineralization. The Dspp−/− dentin (B) showed a low opacity compared to WT (A). The Dspp−/−Bgn−/− showed the lowest opacity in the four groups (C). The Dspp−/−Dcn−/− demonstrated the increased opacity compared to Dspp−/− mice, suggesting that the lack of decorin rescued the DGI phenotypes in Dspp−/− mice (D). (E) Representative data of dentin opacity from WT, Dspp −/−, Dspp −/−Bgn−/− and Dspp−/−Dcn−/−. The statistical analysis was not applied to this data because of the small sample numbers.

Fig. 4. Characteristic comparison of fractured dentin surfaces by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and quantitative analysis by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for the mineral contents (mineral to matrix ratio) in dentin.

(A–D) SEM analysis of incisors. Compared to the WT (A), the collagen fibrils could be clearly observed on the fractured dentin surface of the Dspp−/− mouse (B). The increased number of collagen fibrils was observed on the dentinal tubules and intertubular dentin from Dspp−/− Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/− Dcn−/− samples (arrows in C and D), but much less than those of Dspp−/− (B). Dotted line; dentinal tubles. Bars = 1 μm (E) Quantitative analysis of mineral contents in dentin by FTIR spectroscopy. The WT incisor demonstrated significantly higher mineral contents. *; p<0.05, **; p<0.01, n = 9. The differences in mineral contents did not show significant changes in Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn (E), although dentin hypomineralization appeared to be partially rescued by removing the biglycan or decorin from Dspp−/− mice, based on the SEM observation (A–D).

2.4. Ultrastructural changes of dentin collagen fibrils in Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/− Dcn−/− examined by atomic force microscopy (AFM)

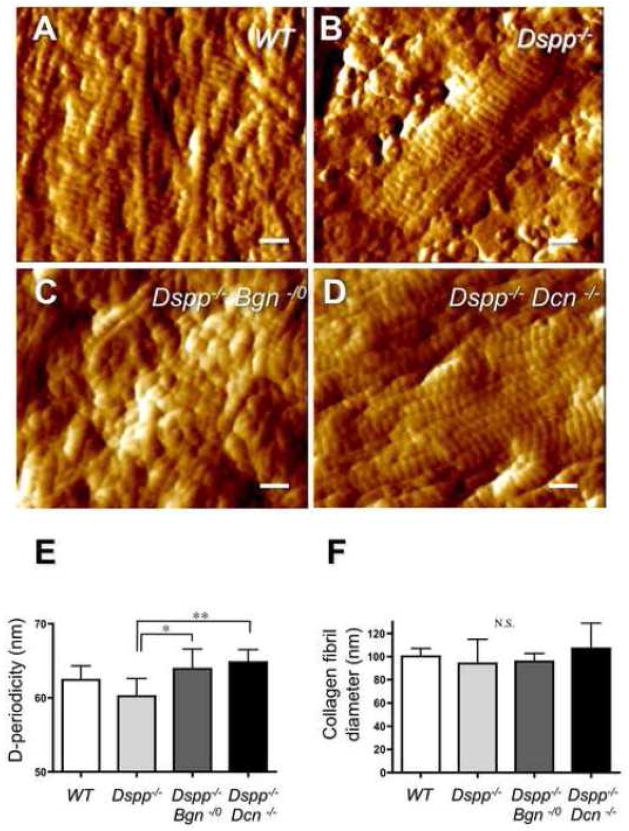

The fractured surfaces of dentin specimens treated by EDTA were used to examine the collagen fibrils by AFM (Fig. 5). After a 3-min 0.5 M EDTA treatment, the collagen fibril structures could not be observed in WT samples because of insufficient decalcification with EDTA (data not shown). With a 5-min 0.5 M EDTA treatment, D-structure (periodicity of the gap zone) was clearly observed (Fig. 5A) in collagen fibrils. In Dspp−/− samples treated by 0.5M EDTA for 3 min, the collagen fibrils and the D-structure could be observed by AFM (Fig. 5B). After a 3-min treatment with EDTA, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− samples also showed the clear collagen fibrils, exposed due to the removal of mineralized material (Fig. 5C and D). The periodicity of the D-structures in Dspp−/− collagen fibrils was significantly shorter than that of the Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 or Dspp−/−Dcn−/− collagen fibrils (Fig. 5E). Although there was no significant difference in the mean values of collagen fibril diameters among the four genotypes, the standard deviations in fibril diameter were bigger in the Dspp−/− (94.0 ± 20.9) and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− (107 ± 21.8) incisors (Fig. 5F) as compared with the WT (100.2 ± 6.8) and Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 (95.7 ± 7.0).

Fig. 5. Collagen microstructures on the decalcified dentin surfaces observed by atomic force microscopy (AFM).

(A) WT incisor after a 0.5 M EDTA treatment for 5 min. The whole surface was covered with the integral D-structure of collagens. (B) Dspp−/− samples treated by 0.5 M EDTA for 3 min. The collagen fibers and the D-structure could be revealed. (C) Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 samples treated by EDTA for 3 min. Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 samples also showed that several collagen fibrils were embossed on the dentin surface. (D) Dspp−/−Dcn−/− samples treated by EDTA for 3 min. The collagen fibrils were well-exposed due to the complete removal of mineralized material. Bars = 200 nm. (E) D-periodicity of the collagen fibrils. The periodicity of the D-structures on Dspp−/− incisor collagen fibers was significantly shorter than that of the Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 or Dspp−/−Dcn−/− collagen fibrils. *; p<0.05, **; p<0.01, n = 9. (F) The mean values of collagen fibril diameters. There was no significant difference in the collagen fibril diameter between the genotypes. The standard deviations in fibril diameter were bigger in the Dspp−/− (94.0 ± 20.9) and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− (107 ± 21.8) incisors (Fig. 5F), as compared with the WT (100.2 ± 6.8) and Dspp−/−Bgn−/0(95.7 ± 7.0). N.S.; not significant, n = 9.

3. Discussion

The non-collagenous ECM proteins are believed to play important roles in the bio-mineralization process that forms hard tissues. In order to characterize the biological roles played by biglycan and decorin in the Dspp−/− teeth, we selectively bred mice to generate deficiency of either biglycan or decorin in the DSPP null background. The width of predentin was almost restored to a normal width in the Dspp−/−Dcn−/−. In contrast, not only the predentin remained widened, but increase in calcospherites was also observed in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 teeth. These results suggest that the widened predentin in Dspp−/− teeth was most likely due to the increased level of decorin in Dspp−/− predentin. In other words, the excess decorin, but not biglycan was responsible for inhibiting conversion of predentin to dentin at the mineralization front in Dspp−/− mice. The excess biglycan may have a positive effect on the coalescence of calcospherites in Dspp−/− mice to a certain extent, but cannot compensate for the failure in predentin/dentin conversion possibly due to the excess decorin.

First, we compared the histological differences in the incisors from four different mouse groups. The dentin in WT was stained relatively purple, whereas the genotypes which lacked DSPP displayed the pale pink-colored dentin layers (Fig. 2). DSPP is not only a highly phosphorylated acidic protein, but it is also the most abundant non-collagenous protein in dentin. Particularly, the acidic peptide: DPP is present only in the mineralized matrices of primary dentin (Rahima et al., 1988). Because the cationic or basic dye such as hematoxylin has an affinity for the tissue with a net negative charge, the removal of phosphate groups might have led to the striking color difference in DSPP null teeth as shown in the H&E staining.

It has been reported that the addition of biglycan increased apatite formation in vitro, suggesting the potential role of biglycan as a nucleator of mineralization (Boskey et al., 1997). Interestingly, the number of calcospherites in the dentin of Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 increased, compared to that of Dspp−/−. The irregularity of mineralization front appeared to be much more increased in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 (Fig. 2C and G), suggesting that the coalescence of calcospherites was severely reduced in Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 dentin. On the other hand, the width of the predentin layer in Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisors dramatically decreased as compared to Dspp−/−, and no (or dramatically fewer) calcospherites were observed, indicating that removing of decorin induces the predentin-dentin conversion in Dspp−/− teeth. These results suggest that the conversion of predentin to dentin at the mineralization front in Dspp−/− mice is regulated positively by biglycan but negatively by decorin.

Both biglycan and decorin single gene knockout mice exhibited altered numbers of collagen fibrils in the molar predentin at a younger age (Goldberg et al., 2005). Type I collagen is secreted by odontoblasts into predentin and then recruited into the mineralization front as bundles of collagen fibrils, thus forming mineralized dentin. Both biglycan and decorin are known to interact with type I collagen fibrils (Schonherr et al., 1995; Weber et al., 1996). Decorin in particular binds to the gap (also referred as ‘D’) region in the collagen fibril, which is believed to block initiation of mineralization (Hoshi et al., 1999). In vitro experiments have also shown such inhibitory functions of proteoglycans in mineralization (Chen et al., 1985). Because the localization of proteoglycans might be one of the key factors in the mineralization process, we hypothesized that the increased decorin protein levels, due to either enhanced expression or decreased degradation, may be one of the key factors which causes widening of the predentin zone observed in Dspp−/− mice. We have previously demonstrated that expression of MMP-3, one of the major proteases that degrades decorin, remains unchanged in Dspp−/− mice (Sreenath et al., 2003), suggesting that the increased expression of decorin prevents recruitment of collagen fibrils during developmental mineralization, which resulted in widened predentin.

It has also been reported that the biglycan single knockout mice did not show any dentin defect in incisors, whereas the mineralization defects found in developing stages of molars were eventually recovered by 6-weeks-old (Goldberg et al., 2005). The decorin single knockout mice also showed that the dentin in 1-day-old molars was porous and poorly mineralized, although the severe mineralization defects were recovered by 6-weeks-old (Goldberg et al., 2005). In this study, we compared the mineralization of biglycan or decorin null teeth with DSPP null background. The microradiographs in Fig. 3 showed that the opacity in the Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 incisor was strikingly decreased, whereas in the Dspp−/−Dcn−/−, the opacity was increased in comparison to that of the Dspp−/− incisor. However, it is conceivable that the thickness ratio between the unmineralized predentin and the mineralized dentin was essential for the altered X-ray opacities observed in the dentin specimens, since the total thickness of predentin and dentin did not seem to be altered between genotypes. To investigate the quality of dentin mineralization, we conducted further observations using SEM and FTIR spectroscopy. Interestingly, dentin hypomineralization appeared to be partially rescued by removing the biglycan or decorin from Dspp−/− mice based on the SEM observation (Fig. 4A–D). However, as shown in Fig. 4E, the quantitative analysis by FTIR used to determined the differences between mineral contents did not show significant changes in Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− dentin. These results suggest that the thickness of mineralized dentin, but not predentin, primarily contributed to the X-ray opacity of dentin, and the ablation of biglycan or decorin may not significantly affect the quality of dentin mineralization in a DSPP null background. In other words, the lack of DSPP could be the causative factor for the hypomineralization of dentin in Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− mice.

We further examined the incisor samples by AFM in order to investigate whether the altered collagen fibrillogenesis or microstructures affect the mineralization in dentin. The typical 60–70nm D-periodicity of the type I collagen was observed in the all genotypes. Although the periodicity of the D-structures in the Dspp−/− incisor was significantly shorter than that of the Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 or Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisors (Fig. 5E), the functional significance of the difference in D-periods could not be determined from our results on dentin mineralization. The difference might simply reflect the change in the susceptibility of tissue shrinkage to the chemical fixation and hydration of the specimens. However, the gap (D zone) regions of type I collagen are considered to be the crystal nucleation sites in biomineralization (Tong et al., 2003). The question of whether the D-periodicity would affect the tissue mineralization remains entirely open-ended. We also demonstrated that there is no significant difference in the mean values of collagen fibril diameter among all four genotypes. However, the standard deviations in fibril diameters were bigger in the Dspp−/− and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisors (Fig. 5F). The variation in fibril diameter apparent in the Dspp−/−Dcn−/− incisor was consistent with one of the key roles of decorin in regulating collagen fibrillogenesis both in vivo and in vitro (Reed et al., 2002). Although the collagen organization and bundles seemed normal (Sreenath et al., 2003), the collagen fibrils with un-uniform diameters may have been present in the collagen bundles of Dspp−/− dentin. Because the microstructures of collagen fibrils and the initiation of dentin mineralization did not show any relationship to one another, the role of biglycan and decorin in the initial mineralization of Dspp−/− dentin might not be acting through the regulation of collagen fibrillogenesis, but perhaps acting through the regulation of key signaling pathways involved in dentin mineralization.

It would be necessary to further investigate the mechanisms of how the deletion of DSPPpositively regulates the expression of biglycan and decorin in odontoblasts. So far, several mutations in the DSPP gene are reported in DGI and DD patients. However, it is well-known that the severity of dentin defect is not correlated with the mutation point, indicating that there are other factors involved in this disease (McKnight et al., 2008b). Biglycan and decorin may be the major candidates for what factors affect these severities, since they seem to act more drastically in DSPP null background than in their single knockout. Most of the DSPP mutations observed in DGI and DD patients are predicted to result in accumulation of mutated DSPP protein in rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) (McKnight et al., 2008a), which may affect the secretion of dentin ECM proteins. Thus, the secretion levels or patterns of biglycan and decorin might affect each individual patient differently, leading to the variety of this disease.

In summary, our genetic studies reveal that increased levels of decorin in predentin of Dspp−/− is associated with a widened predentin phenotype that resembles DGI III. Most importantly, our findings highlight the importance of SLRPs in dentin mineralization.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals

Dspp, Bgn, and Dcn knockout mice were generated as reported previously (Danielson et al., 1997; Sreenath et al., 2003; Xu et al., 1998). Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− mice were generated by sequential breeding of Dspp−/− with Bgn−/− or Dcn−/− mice. The genotyping of WT (Dspp+/+Bgn+/0Dcn+/+), Dspp−/−, Dspp−/−Bgn−/0 and Dspp−/−Dcn−/− mice was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described previously (Bi et al., 2005; Sreenath et al., 2003). Standard NIH guidelines were followed to house, feed and breed the mice. These studies were carried out with the approval of the institutional animal committee.

4.2. Tissue sample preparation, histology and immunohistochemistry

All incisor samples were collected from 6-month-old null and WT control mice. After the mandible and maxilla were dissected, the jaws, including teeth, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight. For histological analysis, the samples were decalcified in 0.1M ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and embedded in paraffin. For the microradiography, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis, the skin and muscles from the heads of the mice were dissected. The brain was also excluded to allow for better diffusion of the fixative solution (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2.0% paraformaldehyde, in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2) for 2 hrs. The skulls were later rinsed in the fixative solution and stored at room temperature for 24 hrs. Five micrometer-thick tissue sections were prepared from paraffin blocks for histology. Only the sections at the cervical level (tooth erupting area) were used as incisor samples. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was performed for general histology on the incisor samples. For the immunohistochemistry, the sections were dewaxed and treated with Peroxidased I (Biocare Medical Concord, CA) for 5 min at RT to inactivate endogenous peroxidase. Next, sections were blocked with Rodent Block M (Biocare Medical) for 30 min at RT, and then incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-BGN (LF-159)(1:800), anti-DCN (LF-113) (1:800) (Fisher et al., 1995) (kind gifts from Dr. Larry Fisher, NIDCR/NIH, Bethesda, MD) for 2h at RT. The immune complexes were incubated with Rodent HRP-Polymer (Biocare Medical) for 30 min, and the peroxidase reaction was visualized by a DAB (3, 3′-Diaminobenzidine) kit (Sigma). Nuclear counterstaining was performed using Hematoxylin for 5 seconds.

4.3. Microradiography

The upper incisors were isolated from the skulls and radiographed using a Faxitron MX20 Specimen Radiography System (Faxitron X-ray Corp., Wheeling, IL) at energy settings 120 s at 15V (Sreenath et al., 2003). The images were captured on X-OMAT TL film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY), and then scanned using a computerized image analysis system. The mean gray values of incisors were measured by Image J (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) to assess the differences in the X-ray opacities.

4.4. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy was performed in order to measure the in situ mineral to matrix ratio in dentin (Boskey et al., 2003). In brief, the specimens were cut transversely at the erupting level of incisors and mounted on glass slides with the cut surface facing up. FTIR spectra were collected using the Perkin-Elmer Spotlight 300 micro-spectroscopy, coupled with a drop-down Ge ATR (attenuate total reflectance) accessory. Spectra were scanned between 4000 and 720 cm−1 at a 4 cm−1 spectral resolution, with 512 scans.

4.5. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis

The incisors for SEM and AFM were fixed as described above, washed and dehydrated. After drying, the specimens were fractured at the erupting level of the incisors for the cross-sectional analysis, and mounted on aluminum stubs with the fractured surface facing upward to a stub. They were then examined using a FEI/Philips XL30 field emission environmental SEM (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands) at 5 kV. The other halves of the same specimens used for SEM observations were further treated with 0.5 M EDTA for either 3 or 5 minutes in order to examine collagen fibril diameters and banding structures by AFM. The AFM images were obtained using a Nanoscope IIIa scanning probe microscope (Digital Instruments, Veeco Metrology Group, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA) operated in contact mode under ambient conditions (24 ± 2°C, 40 ± 5% Relative humidity). Silicon nitride cantilevers (NP-S, Veeco Metrology Group) with a spring constant of approximately 0.06 N/m were used. The diameters and D-structures of collagen fibrils were measured using cross-sectional analysis with Nanoscope software 5.30 version (DI-Veeco, Santa Barbara, CA).

4.6. Statistical analysis

All the graphs are expressed as means ± SD. The data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey’s test to identify differences between groups, except for the data in Fig. 3E.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Changqi Xu for the AFM data analysis. We would like to thank Harry Grant for the editorial assistance. These studies were supported by the Intramural Division of National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bi Y, Stuelten CH, Kilts T, Wadhwa S, Iozzo RV, Robey PG, Chen XD, Young MF. Extracellular matrix proteoglycans control the fate of bone marrow stromal cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30481–30489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boskey AL, Moore DJ, Amling M, Canalis E, Delany AM. Infrared analysis of the mineral and matrix in bones of osteonectin-null mice and their wildtype controls. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1005–1011. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boskey AL, Spevak L, Doty SB, Rosenberg L. Effects of bone CS-proteoglycans, DS-decorin, and DS-biglycan on hydroxyapatite formation in a gelatin gel. Calcif Tissue Int. 1997;61:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s002239900339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Boskey AL. Mechanisms of proteoglycan inhibition of hydroxyapatite growth. Calcif Tissue Int. 1985;37:395–400. doi: 10.1007/BF02553709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–743. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embery G, Hall R, Waddington R, Septier D, Goldberg M. Proteoglycans in dentinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12:331–349. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng JQ, Luan X, Wallace J, Jing D, Ohshima T, Kulkarni AB, D’Souza RN, Kozak CA, MacDougall M. Genomic organization, chromosomal mapping, and promoter analysis of the mouse dentin sialophosphoprotein (Dspp) gene, which codes for both dentin sialoprotein and dentin phosphoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9457–9464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous Z, Wei VM, Iozzo R, Hook M, Grande-Allen KJ. Decorin-transforming growth factor-interaction regulates matrix organization and mechanical characteristics of three-dimensional collagen matrices. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35887–35898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Six genes expressed in bones and teeth encode the current members of the SIBLING family of proteins. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44(Suppl 1):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Stubbs JT, 3rd, Young MF. Antisera and cDNA probes to human and certain animal model bone matrix noncollagenous proteins. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1995;266:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Termine JD, Young MF. Deduced protein sequence of bone small proteoglycan I (biglycan) shows homology with proteoglycan II (decorin) and several nonconnective tissue proteins in a variety of species. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4571–4576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Torchia DA, Fohr B, Young MF, Fedarko NS. Flexible structures of SIBLING proteins, bone sialoprotein, and osteopontin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:460–465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M, Septier D, Rapoport O, Iozzo RV, Young MF, Ameye LG. Targeted disruption of two small leucine-rich proteoglycans, biglycan and decorin, excerpts divergent effects on enamel and dentin formation. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77:297–310. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking AM, Shinomura T, McQuillan DJ. Leucine-rich repeat glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi K, Kemmotsu S, Takeuchi Y, Amizuka N, Ozawa H. The primary calcification in bones follows removal of decorin and fusion of collagen fibrils. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:273–280. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. The family of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: key regulators of matrix assembly and cellular growth. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:141–174. doi: 10.3109/10409239709108551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. The biology of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Functional network of interactive proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18843–18846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV, Murdoch AD. Proteoglycans of the extracellular environment: clues from the gene and protein side offer novel perspectives in molecular diversity and function. Faseb J. 1996;10:598–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse H, Schonherr E. Proteoglycans of the extracellular matrix and growth control. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:266–274. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusius T, Ruoslahti E. Primary structure of an extracellular matrix proteoglycan core protein deduced from cloned cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7683–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall M. Dental structural diseases mapping to human chromosome 4q21. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44(Suppl 1):285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall M, Dong J, Acevedo AC. Molecular basis of human dentin diseases. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:2536–2546. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall M, Simmons D, Luan X, Nydegger J, Feng J, Gu TT. Dentin phosphoprotein and dentin sialoprotein are cleavage products expressed from a single transcript coded by a gene on human chromosome 4. Dentin phosphoprotein DNA sequence determination. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:835–842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markmann A, Hausser H, Schonherr E, Kresse H. Influence of decorin expression on transforming growth factor-beta-mediated collagen gel retraction and biglycan induction. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:631–636. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight DA, Simmer JP, Hart PS, Hart TC, Fisher LW. Overlapping DSPP mutations cause dentin dysplasia and dentinogenesis imperfecta. J Dent Res. 2008a;87:1108–1111. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight DA, Suzanne Hart P, Hart TC, Hartsfield JK, Wilson A, Wright JT, Fisher LW. A comprehensive analysis of normal variation and disease-causing mutations in the human DSPP gene. Hum Mutat. 2008b;29:1392–1404. doi: 10.1002/humu.20783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Baba O, Butler WT. Post-translational modifications of sibling proteins and their roles in osteogenesis and dentinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:126–136. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahima M, Tsay TG, Andujar M, Veis A. Localization of phosphophoryn in rat incisor dentin using immunocytochemical techniques. J Histochem Cytochem. 1988;36:153–157. doi: 10.1177/36.2.3335773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CC, Iozzo RV. The role of decorin in collagen fibrillogenesis and skin homeostasis. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:249–255. doi: 10.1023/A:1025383913444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Biological Functions of the Small Leucine-rich Proteoglycans: From Genetics to Signal Transduction. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21305–21309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800020200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr E, Witsch-Prehm P, Harrach B, Robenek H, Rauterberg J, Kresse H. Interaction of biglycan with type I collagen. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2776–2783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenath T, Thyagarajan T, Hall B, Longenecker G, D’Souza R, Hong S, Wright JT, MacDougall M, Sauk J, Kulkarni AB. Dentin sialophosphoprotein knockout mouse teeth display widened predentin zone and develop defective dentin mineralization similar to human dentinogenesis imperfecta type III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24874–24880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W, Glimcher MJ, Katz JL, Kuhn L, Eppell SJ. Size and shape of mineralites in young bovine bone measured by atomic force microscopy. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;72:592–598. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-1077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber IT, Harrison RW, Iozzo RV. Model structure of decorin and implications for collagen fibrillogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31767–31770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Bianco P, Fisher LW, Longenecker G, Smith E, Goldstein S, Bonadio J, Boskey A, Heegaard AM, Sommer B, Satomura K, Dominguez P, Zhao C, Kulkarni AB, Robey PG, Young MF. Targeted disruption of the biglycan gene leads to an osteoporosis-like phenotype in mice. Nat Genet. 1998;20:78–82. doi: 10.1038/1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi Y, Hu JC, Fukae M, Zhang H, Simmer JP. Dentin glycoprotein: the protein in the middle of the dentin sialophosphoprotein chimera. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17472–17479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]