A 68-year-old Canadian woman originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo returned to Canada after a 10-month stay in the Congo where she was visiting friends and relatives. She had taken no chemoprophylaxis for malaria and sought no pretravel advice. Three days after returning to Canada, she began to have fever, nausea and vomiting. She visited a walk-in clinic, but she was sent home with no specific therapy. Later that day, she presented to an emergency department, and she was again discharged home. Four days after the onset of symptoms, she was taken to the emergency department by her family, who found her to be lethargic, confused, feverish and incontinent. Thick and thin smears for malaria were performed. An infection of Plasmodium falciparum was detected, with 35% parasitemia (Figure 1). The patient was transferred to our hospital, where she was admitted to the intensive care unit. She was given quinine intravenously and 1 cycle of exchange transfusion. Although she had hypoglycemia (glucose in random samples 3.1 mmol/L), hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 78 μmol/L), mild acute renal failure (creatinine 119 μmol/L) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count 16 × 109 cells/L), her symptoms responded well to quinine and a solution of 10% dextrose in water. Within 24 hours, she was coherent and afebrile.

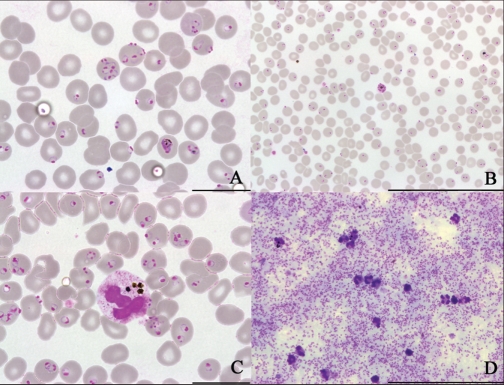

Figure 1.

A-C, microscopic images of thin films showing Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia of 35% (A and C: bar = 20 μm; B: bar = 100 μm, Giemsa stain). D, microscopic image of thick film reflecting high density P. falciparum infection (bar = 200 μm, Giemsa stain).

Repeat malaria smears performed 12, 24, and 48 hours after admission revealed parasitemia of 9.5%, 3% and < 1%, respectively. Intravenous quinine therapy was stopped and her treatment course was completed with quinine and doxycycline taken orally for 7 days total. She was discharged after 3 days in hospital. At this time, she had normoglycemia (glucose in random samples 4.2 mmol/L), mild anemia (hemoglobin 103 g/L) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count 76 × 109 cells/L). There was no parasitemia at discharge, and she was well 6 months after discharge.

Discussion

Malaria is a potentially fatal, but readily treatable, condition. This case highlights the importance of obtaining a travel history for febrile patients and including malaria in the differential diagnosis for those who have recently travelled to regions where malaria is endemic. Fever is a common manifestation of travel-acquired illness and occurs in about one-quarter of returning travellers who visit post-travel clinics.1,2

Clinical presentation

Malaria is caused by protozoan parasite members of the genus Plasmodium and is transmitted via bites from infected Anopheles mosquitoes. Almost all deaths due to severe malaria are caused by infection with P. falciparum (Box 1).

Box 1.

Criteria for diagnosing severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria16

Detection of asexual forms of P. falciparum on a bloodsmear or a compatible history

AND

One or more of the following:

Severe normocytic anemia (hemoglobin < 50 g/L)

Impaired consciousness or unrousable from a coma with a score less than 10 on the Glasgow Coma Scale

Shock with systolic blood pressure < 80 mm Hg

Prostration with extreme weakness

Acute renal failure with a urine output < 400 mL in 24 hours and serum creatinine > 265 μmol/L

Pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome

Hypoglycemia (plasma glucose < 2.2 mmol/L)

Spontaneous bleeding or disseminated intravascular coagulation

Repeated generalized convulsions (> 2 within 24 hours)

Acidemia or acidosis (arterial pH < 7.25, plasma bicarbonates < 15 mmol/L or venous lactate > 15 mmol/L)

Macroscopic hemoglobinuria not associated with oxidant drugs and RBC enzyme defects

Jaundice detected clinically or total serum bilirubin > 50 μmol/L

Parasitemia of > 5% in people who are not immune to P. falciparum infection

Adapted from Boggild AK and Kain KC. Malaria: clinical features, management, and prevention. In: Heggenhougen HK, Quah S, editors. International encyclopedia of public health. Vol.5. p. 371–382. Copyright Elsevier Science (2008).4

Fever is a common chief complaint of patients with malaria and occurs in 80%–90% of cases.3–6 Other symptoms, such as malaise, coughing, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain or headache, may be predominant. More than 90% of patients with malaria caused by P. falciparum show symptoms within 1 month of returning from travel. Almost all present for care within 2 months of the initial infection, although this may be delayed if the patient has taken chemoprophylaxis.1,6,7

Malaria is endemic throughout the tropics and subtropics. The prevalence of malaria is high in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Oceania, where the relative risks of malaria among travellers are 207.6 and 76.7, respectively.7 Malaria can be prevented by a combination of mosquito-avoidance measures (e.g., mosquito netting, insect repellents, coils and sprays) and chemoprophylactic agents. No chemoprophylactic agent is 100% effective; thus, malaria should still be considered in febrile patients who have taken prophylaxis. Obtaining a detailed travel history, including destination, nature and duration of travel and adherence to preventive measures, in addition to a clinical history, is essential for diagnosing malaria.

About 400 cases of malaria occur each year in travellers returning to Canada. Most of these cases are caused by infection with P. falciparum, which can quickly lead to severe and potentially fatal disease in people who are not immune, including tourists, business travellers and people visiting friends and relatives. Although many people who grew up in countries where malaria is endemic believe themselves to be immune,7,8 immunity begins to wane within 6 months of departure from the endemic area in the absence of re-exposure.9–11 Thus, malaria should be included in the differential diagnosis of fever for people who were born in or previously lived in areas where malaria is endemic.

Malaria in children

Children born in countries where malaria is not endemic who travel to areas with malaria (e.g., their parents’ place of birth) represent a particularly vulnerable group of travellers. In this group of children, reported adherence to appropriate chemoprophylaxis is only 3%–15%. This may be, in part, attributed to the false assumption on the part of parents that their children are protected because of their ethnic background.12,13 In many European countries, the greatest number of imported cases of malaria are among children.12 Peak incidences of imported malaria in children visiting friends and relatives coincide with school holidays, mainly during the summer months and December and January.12

Children are more likely than adults to present with non-specific symptoms, such as fever, lethargy and malaise, and gastrointestinal complaints, such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea. They are also more likely to have hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice. Children, especially those under 5 years of age, are more vulnerable to severe and cerebral manifestations of malaria.4,6,12

Making the diagnosis

Of the imported cases of P. falciparum malaria in Canada, about 15 per year will have severe manifestations, leading to 1–2 deaths annually.6 Inadequate or no chemoprophylaxis, the inability of health care providers to recognize the importance of fever in returned travellers, and the delayed initiation of treatment all contribute to the burden of severe imported malaria in Canada.6,14 Exclusion of malaria requires 3 separate blood smears performed and promptly read at 12-hour intervals over a 24–48 hour period.5,6 If a dipstick assay is used, it must be followed up with confirmatory blood smears, which allow for quantification of parasitemia and a determination of the species.

In this case, the patient made a complete recovery, despite having greater than 30% parasitemia and systemic involvement; this is an atypical result. A recent case series described 7 cases of fatal imported malaria in Canadian travellers or visitors to Canada.14 None of these patients had the level of parasitemia observed in our patient. Although prompt initiation of parenteral antimalarial therapy can be life-saving for those with severe malaria, the fatality rate in this group remains between 10% and 30%, even if patients receive appropriate therapy.4,6 Thus, recognition of malaria as a potential cause of illness in returned travellers, coupled with early diagnosis and initiation of treatment before the development of severe manifestations, provides the greatest likelihood of a successful clinical outcome. Uncomplicated malaria is easily treated with short courses of antimalarial drugs taken orally. Most patients who receive quick diagnosis and treatment recover uneventfully. Physicians should strongly consider seeking support from a consultant or an expert in infectious diseases for any patient in whom the diagnosis of malaria is confirmed (Box 2).

Box 2.

Malaria and travel-related resources for health care providers

Travel

Public Health Agency of Canada

Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/contentYellowBook.aspx

wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/

World Health Organization

United Kingdom’s National Travel Health Network and Centre

International Society of Travel Medicine

Malaria

World Health Organization

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Prevention and treatment

Public Health Agency of Canada

World Health Organization

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Surveillance and outbreak information

Canada Communicable Disease Report

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

WHO Weekly Epidemiological Record

ProMedmail

Malaria continues to pose a diagnostic dilemma for physicians in countries where it is not endemic.5,14,15 This case is a reminder to all front-line clinicians to suspect malaria in returning travellers who present with fever and to obtain a travel history, particularly if the patient’s primary complaint is fever.

Key points

Malaria should be considered and excluded for any traveller with fever returning from an area where malaria is endemic, regardless of their country of birth.

People travelling to visit friends and relatives are less likely than other travellers to seek pretravel advice or to take chemoprophylaxis, and they are more likely to travel to rural areas for prolonged periods.

Malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum can quickly progress to severe complications and death, especially in those who are not immune.

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are essential for successful outcomes.

The section Cases presents brief case reports that convey clear, practical lessons. Preference is given to common presentations of important rare conditions, and important unusual presentations of common problems. Articles start with a case presentation (500 words maximum) and a discussion of the underlying condition follows (1000 words maximum). Generally, up to 5 references are permitted and visual elements (e.g., tables of the differential diagnosis, clinical features or diagnostic approach) are encouraged. Written consent from patients for publication of their story is a necessity and should accompany submissions. See information for authors at www.cmaj.ca.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson ME, Weld LH, Boggild A, et al. Fever in returned travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1560–8. doi: 10.1086/518173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, et al. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:119–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boggild AK, Yohanna S, Keystone JS, et al. Prospective analysis of parasitic infections in Canadian travelers and immigrants. J Travel Med. 2006;13:138–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boggild AK, Kain KC. Malaria: clinical features, management, and prevention. In: Heggenhougen HK, Quah S, editors. International encyclopedia of public health. Vol. 5. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; 2008. pp. 371–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman RD, Parise ME, Barber AM, et al. Malaria-related deaths among US travelers, 1963–2001. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:547–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suh KN, Kain KC, Keystone JS. Malaria. CMAJ. 2004;170:1693–702. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1030418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman DO. Malaria prevention in short-term travelers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:603–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0803572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, et al. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1185–93. doi: 10.1086/507893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colbourne MJ. Malaria in Gold Coast students on their return from the United Kingdom. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:483–7. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor TE, Strickland GT. Malaria. In: Strickland GT, editor. Tropical medicine and emerging infectious diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 614–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mascarello M, Allegranzi B, Angheben A, et al. Imported malaria in adults and children: epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 380 consecutive cases observed in Verona, Italy. J Travel Med. 2008;15:229–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ladhani S, Aibara RJ, Riordan FAI, et al. Imported malaria in children: a review of clinical studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:349–57. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley D, Warhurst D, Blaze M, et al. Malaria imported into the United Kingdom in 1992 and 1993. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev. 1994;4:R169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kain KC, MacPherson DW, Kelton T, et al. Malaria deaths in visitors to Canada and in Canadian travellers: a case series. CMAJ. 2001;164:654–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mali S, Steele S, Slutsker L, et al. Malaria surveillance — United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:24–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94(Suppl 1):1–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]