Abstract

Our aim in conducting this study was to analyze the relationships between violence and maternal psychological distress 8 months after a birth, taking into account other important psychosocial factors, known to be associated both with violence and with new mothers’ mental health. A total of 352 women responded to a questionnaire after the birth at a maternity hospital in northern Italy, and 292 also participated in a telephone interview 8 months later. We evaluated psychological distress with the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), and partner and family violence with a 28-item scale. Eight months postpartum, 5% of women showed high psychological distress; 10% were currently experiencing violence from the partner or another family member. After adjustment for covariates, the odds ratio for depressive symptoms was 13.74 for women experiencing violence. We believe that these results provide support for the important role of violence in postpartum maternal psychological distress.

In this article we examine the contributions of violence and other psychosocial factors to women’s postpartum mental health. Our aim was to analyze the relationships between violence and maternal psychological distress 8 months after a birth, taking into account other important psychosocial factors known to be associated both with violence and with new mothers’ mental health. Violence experienced by women during the postpartum period most certainly contributes to maternal distress and may lead to depression; moreover, domestic violence and maternal depression both represent serious risk factors for child development.

BACKGROUND

In the last decades, an impressive number of investigators have described the impact of violence, and more particularly partner violence, on women’s physical and mental health (Campbell, 2002; Koss, Bailey, Yuan, Herrera, & Lichter, 2003) to the point that the WHO (1997) has defined violence as one of the most important health risk factors for women of reproductive age. Researchers also have addressed the question of violence during or just before pregnancy, showing that violence against pregnant women is frequent (Campbell, Garcia-Moreno, & Sharps, 2004), and that it may negatively affect both their physical and mental health (Leung, Kung, Lam, Leung, & Ho, 2002; Martin et al., 2006) and the health of their baby (Aslig-Monemi, Pena, Ellsberg, & Persson, 2003; Coker, Sanderson, & Dong, 2004; Murphy, Schei, Myhr, & Du Mont, 2001).

Much less is known about violence in the postpartum period and its possible association with women’s mental health, and more particularly postpartum depression. There are two possible reasons for this paucity. There is an idealized vision of the postpartum period, with the expectation that at this time the partner and other relatives lovingly support the new mother and therefore a deep uneasiness with imagining violence. In addition, a biomedical model of postpartum depression, which downplays the role of psychosocial factors, is predominant (Martinez, Johnston-Robled, Ulsh, & Chrisler, 2000). Researchers to date, however, have shown that partner violence is not uncommon in the months following childbirth, with rates ranging from 2% of postpartum women experiencing physical abuse in a nationwide Swedish sample (Radestad, Rubertsson, Ebeling, & Hildingsson, 2004) to 19% reporting “moderate to severe” physical or psychological violence among disadvantaged U.S. women (Gielen, O’Campo, Faden, Kass, & Xue, 1994). In this U.S. study and in a study in China (Guo, Wu, Qu, & Yan, 2004) the authors found that violence was even more common in the postpartum period than during pregnancy. Moreover, the few investigators who have looked at the health impact of partner violence after birth found that this violence is associated with mothers’ depression (Leung et al., 2002; Saurel-Cubizolles, Blondel, Lelong, & Romito, 1997). Violence, be it associated with depression or not, is obviously a source for distress for the woman herself; moreover, domestic violence and maternal depression both represent serious risk factors for child development (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003; Murray & Cooper, 1997).

To intervene effectively to protect and promote women’s and children’s health, we need to understand more thoroughly the relationships between violence and women’s mental health in the postpartum period. First, different types of violence and different perpetrators should be considered; investigators to date tended to consider mostly partner physical violence. Second, the relative contribution of violence to maternal mental health should be analyzed. Previous investigators studying violence around pregnancy have shown that a number of demographic and psychosocial variables such as unemployment and work dissatisfaction, migrant status, financial problems, and an unwanted pregnancy are associated with partner violence (Saltzman, Johnson, Colley Gibert, & Goodwin, 2003; Saurel-Cubizolles & Lelong, 2005). Having experienced violence in childhood puts a woman at higher risk for experiencing violence from a partner later in life (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1997). As all these variables represent important risk factors for postpartum depression (Dennis, Janssen, & Singer, 2004; Glasser et al., 1998; Lang, Rodgers, & Lebeck, 2006; Romito, Saurel-Cubizolles, & Lelong, 1999; Saurel-Cubizolles, Romito, Ancel, & Lelong, 2000), it is necessary to unravel their relative contribution to new mothers’ mental health. Another question concerns the role of difficulties in the couple relationship. Conflicts with the partner or dissatisfaction concerning his or her behavior are strongly related to postnatal depression (Romito et al., 1999). Given the possibility of partner violence, it would be interesting to understand whether this association is mostly explained by violence.

In this study we aimed to respond to the questions presented above. Specifically, we aimed to analyze the relationships between current violence and maternal psychological distress 8 months after birth, taking into account other important psychosocial factors known to be associated both with violence and with new mothers’ mental health in the Italian cultural setting.

The Context of the Study: Italy and Trieste

We carried out this longitudinal study in Trieste, a city of 210,000 inhabitants located in Northeastern Italy. Italy has contradictory characteristics related to motherhood. Notwithstanding the strong Catholic tradition, the total fertility rate currently falls into the category of “lowest-low fertility” (Billari & Kohler, 2004). Medical care in pregnancy is free, as well as induced abortion services. A recent cause for concern has been the fact that Italy has the highest cesarean section rate in Europe; 37% of all deliveries (Pinnelli, Racioppi, & Terzera, 2007). The Italian maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is one of the lowest in the world: 3/100,000 live births (in the United States the MMR is 11/100,000; Hill et al., 2007). Maternity leave and other protections for working mothers are fairly generous. As family ties are strong and geographical mobility is low, parents and in-laws usually provide a great deal of assistance to new mothers (Neyer, 2004). In the Trieste region, where the research was conducted, the fertility rate and the MMR rate are even lower than in the rest of Italy (Italian Health Ministry, 2007). Perinatal care offered in the city is of good quality, the c-section rate is lower than in Italy as a whole, and breastfeeding rates are higher than in the rest of Italy (Pinnelli et al., 2007). On the whole, Northeastern Italy seems to have a very supportive environment for childbearing. In a comparative study carried out in selected regions of Italy, France, and Québec, women in the region of Trieste reported the lowest levels of postpartum psychological problems (Des Rivieres-Pigeon, Saurel-Cubizolles, & Romito, 2003).

METHODS

We carried out this study at the Trieste maternity hospital, where more than 95% of the births occurring in the city take place. From January to April 2004, we approached all women who had given birth in the postnatal ward at a time when they did not have visitors, and asked them to participate. We presented the study as research on the health of women during pregnancy, and we assured the women confidentiality of their responses. Women who refused to participate were asked to respond to a few questions (nationality, age, marital status, and type of birth). We assured all women that their participation or nonparticipation in the study would not affect their own or their baby’s health care. We used a questionnaire to interview all women who accepted, and we asked them if they would agree to respond to a follow-up telephone interview 8 months later. The women gave oral informed consent.

We developed the questionnaires for this study from those used in previous Italian investigations on postpartum depression (Romito et al., 1999). The new questionnaires were validated by administration to a small sample of new mothers (not participating in the study). Based on this pretest, including probing and clarification of responses, we discarded or modified unsatisfactory questions.

Well-trained female research staff, knowledgeable about violence against women and about postpartum depression, carried out the interviews. The interviewers were informed of the resources available in the city for victims of violence and for depressed mothers and had at hand leaflets with the relevant information. Before beginning the study, contacts were established with the hospital social worker and with the local women’s center and women’s shelter, in case a woman requested a referral. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital.

Instruments and Measures

We used two different questionnaires. Questions in the immediate post-partum questionnaire included social and demographic characteristics, pregnancy intendedness, the woman’s health and health behavior during and prior to the pregnancy, childbirth, the health of the baby, and experience of violence.

In the second questionnaire, 8 months after the birth, we designed questions to address the baby’s health, breast-feeding, resumption of sexual activity, physical and mental health, working situation, couple relationship, the sharing of housework and baby care, and past and present violence.

Present and Past Violence

No specific instruments exist designed to investigate violence against women in the period following a birth. To assess current violence, we developed a detailed series of 28 questions, adapted from a series of previous studies on violence against women in Italy (Romito, Turan, & De Marchi, 2005), covering psychological violence (insults, humiliation, domination and controlling behavior) and physical and sexual violence (threatening, yelling and smashing things, physical or sexual aggressions) that occurred after the birth. Some items (for instance, criticizing and degrading the woman’s competence as a mother) were adapted to the specific situation of a new mother. Possible answers were “not at all,” “occasionally,” or “more than occasionally.”

In the questionnaires, we asked women to respond to the questions regarding violence, first asking about partner’s behavior, and then about the behavior of other people, whom the woman was asked to specify. In the context of a couple relationship, the classification of some of these items as violence, such as pressures not to have another baby, taken in isolation, could be ambiguous. Therefore, women were considered to have experienced “present partner violence” when they answered positively to at least two abusive items. As the other perpetrators mentioned by women were exclusively family members (such as parents or in-laws), we constructed a variable called “present family violence,” including all women who had answered positively to at least one abusive item. These questions were used to construct a synthetic variable for the analysis, called “any present violence,” including “present partner” or “present family” violence at the time of the postpartum interview.

We included three questions to investigate past violence. We asked women whether, as a child or an adolescent, they had experienced physical, psychological, or sexual violence, and by whom. As most of this violence was perpetrated by family members, we constructed a synthetic variable called “past family violence,” including all women who had experienced any kind of violence by a family member in the past.

Present and Past Psychological Distress

We measured present psychological distress with the GHQ (Goldberg, 1972), in its 12-item version. This screening instrument has been internationally validated (Goldberg et al., 1997). It covers anxiety, depression, and self-esteem, as experienced in the last month. It has the advantage of having been widely used with women in the perinatal period (Gavin et al., 2005) and in studies on the mental health impact of violence, in both cases also with Italian samples (Golding, 1999; Romito et al., 1999; Romito et al., 2005). While a cut-off point of >2 positive answers is generally used as a screening measure, a cut-off point of >5 was chosen for this study to select a group of more seriously distressed women. Women classified as showing “high psychological distress” in this study gave an answer indicating distress to at least half of the items on the GHQ. In the analyses, a dichotomous variable was used: GHQ score 0–5 versus GHQ score 6–12.

To analyze women’s previous mental health, we used two questions from the first questionnaire. Women were asked whether, before the pregnancy, they had “frequent feelings” of depression or “frequent feelings” of anxiety. In the present analyses, we combined these two variables into one: reporting of frequent feelings of depression or anxiety before pregnancy.

Concurrence of the Partners’ Intentions Concerning the Pregnancy

In the first questionnaire, we asked whether the pregnancy was wanted in the same way by the woman and her partner, unwanted in the same way, she wanted it more, he wanted it more, she had almost forced the pregnancy on him, or he had almost forced the pregnancy on her. The question was recoded in two categories: “both wanted to the same extent,” including the first answer; and “other,” including all the other responses. Another question concerned couple decision-making on contraception before the pregnancy. Answers follow: Contraception was (1) mostly decided by the woman, (2) mostly decided by the man, (3) decided together, (4) disagreed on, or (5) unnecessary because they wanted a baby. The question was recoded into two categories. One category, called “decided together,” included answers 3 and 5, and the category “other” included all the other answers.

Women’s Working Status Postpartum

In the second questionnaire, we asked women about their present work situation. Another question concerned the congruence between women’s wishes and reality. Possible answers follow: (1) I am at home but would prefer to be working; (2) I am at home and happy with that; (3) I am working and happy with that; (4) I am working but would prefer to stay at home; (5) I am working full time, but would prefer a part-time job. Answers 2 and 3 were recoded into one category, referred to as satisfied with current work situation. Answers 1, 4, and 5 were recoded as dissatisfied with current work situation. An additional question asked the woman if, since the birth, she had experienced any problems concerning work.

Strategy of Analysis

After initial examination of bivariate relationships between demographic, violence, and other psychosocial variables and high psychological distress in the postpartum period, we used multivariate logistic regression to examine the relative importance of violence, controlling for other important predictors of distress. We conducted mediation analyses using probit regression to obtain estimates of the indirect effects of financial problems and past family violence on postpartum depression.

RESULTS

Response Rate

Among the 389 women whom we approached in the maternity ward, 352 agreed to participate. Among the 37 nonparticipating women, 57% were not Italian and did not speak Italian at all. Nonparticipating women were younger (mean age 28.9 vs. 32.4 for participating women), and they were more likely to have undergone a caesarean section (30% vs. 22%). There were no differences according to marital status.

Among the 352 women who responded to the immediate postpartum questionnaire, 333 agreed to participate in a follow-up interview 8 months later. From September 2004 to March 2005, they were contacted by telephone, reminded about the study, and asked to respond to a questionnaire at a convenient time. Overall, 292 women were successfully contacted and completed the second questionnaire (83%). The mean age of the babies at the time of the interview was 33.7 weeks (s.d. 1.6 weeks).

The 60 women lost to follow-up were significantly more likely to be non-Italian, not married, and under 25 years of age, as compared with women who completed the postpartum questionnaire. There were no differences according to the woman’s evaluation of her living standards, number of children, type of childbirth, baby’s birth weight, or gestational age.

Characteristics of the Sample

Respondents’ mean age was 32.6 (SD = 4.4); only 4% were younger than 25 years; 57% had recently given birth to their first child. Most were Italians (92%), with a high school or university degree (73%), married (82%), and living with the baby’s father (97%). Twelve percent of the women reported financial problems at the time of the second interview; this was significantly associated with unemployment of the woman or her partner and with housing problems. Eleven percent of women reported that their baby had been hospitalized in the 8 months since discharge from the maternity ward; babies with a low birth weight were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized.

Psychological Distress

Fifteen women (5.1%) had GHQ scores >5, and 14% reported frequent feelings of anxiety or depression before pregnancy.

Working Situation

Eight months postpartum, 40% of the women were back at work, 36% were on maternity leave, 8% defined themselves as unemployed, and 15% as homemakers (5 women in “other” situations were excluded from these analyses). The proportion of women discontent with their working status was around the same among those working and those staying at home (33% and 29%, respectively). Overall, 32% of women were not satisfied with their current working status; 13% of the sample reported problems related to work since childbirth, such as being fired, looking unsuccessfully for a job, or having difficulties in negotiating a change in working hours. These problems concerned both working women and those not working, and there was no association with their current working status.

Couple Relationship

In 14% of couples, the partners did not concur on wantedness of the pregnancy, and in 17%, they did not decide together about contraception. At the second interview, 16% of the women said that they had not felt ready when they had resumed sexual intercourse after birth. Concerning the couple relationship, 49% evaluated it as “very good,” 37% as “good,” and 13% as “not good.”

Present and Past Violence

Fifteen women (5%) were currently experiencing violence from their partner 8 months after the birth. Violence was psychological in nine cases; in six cases (2% of the sample), it included threats, yelling and smashing things, or other serious physical or sexual aggressions. Seventeen women (6%) were experiencing abuse, exclusively psychological, perpetrated by a family member. Women who reported partner violence also were more likely to report family violence than those without partner violence (respectively, 20.0% vs. 5.1%, p = .05). Overall, 8 months after birth, 29 women (10%) were experiencing violence, either from the partner or from another family member.

Twenty-eight women (9.5%) reported physical, psychological, or sexual violence during childhood, perpetrated by a family member.

Bivariate Analyses: Factors Associated With Women’s Psychological Distress

Age, nationality, education, number of children, marital status, and living with a partner were not associated with high GHQ scores (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Women’s Demographic and Social Characteristics and Psychological Distress 8 Months Postpartum

| % with GHQ>5 p value from chi-square test | |

|---|---|

| All (292) | 5.1 |

| Age* | |

| <25 (11) | 9.1 |

| 25–29 (55) | 3.6 |

| 30–34 (125) | 5.6 |

| >34 (100) | 5.0 |

| ns | |

| Nationality* | |

| Italian (269) | 5,9 |

| Non-Italian (22) | 4,5 |

| ns | |

| Education* | |

| < = Middle school (79) | 5.1 |

| High school (135) | 5.9 |

| > = University (77) | 3.8 |

| ns | |

| # of children* | |

| 1 (164) | 4.8 |

| 2 or more (127) | 5.5 |

| ns | |

| Marital status | |

| Married (239) | 4.6 |

| Never married (33) | 6.1 |

| Separated/divorced (19) | 10.2 |

| ns | |

| Lives with a partner | |

| Yes (283) | 5.2 |

| No (8) | 0 |

| ns | |

| Financial problems | |

| No (257) | 3.5 |

| Yes (34) | 17.6 |

| p = 0.004 | |

| Baby hospitalized | |

| No (260) | 3.8 |

| Yes (31) | 16.1 |

| p = 0.03 | |

| Frequent feelings of anxiety or depression before pregnancy* | |

| No (251) | 2.8 |

| Yes (41) | 19.5 |

| p < 0.001 | |

| Women’s working situation | |

| Working situation | |

| At work (116) | 3.4 |

| Maternity leave (105) | 6.7 |

| Unemployed (22) | 9.1 |

| Homemaker (44) | 2.3 |

| ns | |

| Work: wishes and reality | |

| At home, prefers to work (30) | 16.7 |

| At home, as preferred (73) | 0 |

| At work, as preferred (124) | 2.4 |

| At work, prefers to be at home (61) | 9.8 |

| p < .001 | |

| Work: wishes and reality (synthesis) | |

| Dissatisfied (94) | 12.8 |

| Satisfied (197) | 1.5 |

| p < .001 | |

| Problems concerning work | |

| Yes (37) | 21.6 |

| No (254) | 2.7 |

| p < .001 | |

Asked in the first questionnaire.

Women reporting financial problems were significantly more distressed than the others (17.6% vs. 3.5%, p = .004). The women’s actual working status was not associated with depression, while the congruence between what the woman was doing and her wishes was related. Working mothers who preferred to be at home or work fewer hours, and especially homemakers who preferred to be at work, were significantly more distressed (respectively, 9.8% and 16.7%) than mothers who stayed at home (0%) or who worked (2.4%), when that was what they wanted to be doing (p < .001). Reporting problems concerning work was also significantly associated with high GHQ scores (21.6% vs. 2.7%, p = .001).

When the baby had been hospitalized after the birth, mothers showed significantly more distress (16.1% vs. 3.8%, p = .03). On the other hand, type of childbirth, baby’s gestational age and birth weight, breast-feeding status 8 months postpartum, and contraception after birth showed no association with GHQ scores (data not shown).

Having experienced frequent feelings of anxiety or depression before the pregnancy was strongly associated with current psychological distress (19.5% vs. 2.8%, p < .001).

All the indicators of the quality of couple relationship showed significant associations with maternal distress (see Table 2). The lack of concurrence between partners concerning contraception before pregnancy and concerning pregnancy intendedness, the woman’s feeling that she had resumed sex before she was ready, her negative evaluation of the couple relationship and of the father’s play interaction with the baby, all were strongly associated with high GHQ scores 8 months postpartum.

TABLE 2.

Relationship With the Partner, Present and Past Violence, and Psychological Distress 8 Months Postpartum

| % with GHQ >5 p value from chi-square test | |

|---|---|

| Couple Relationship | |

| Couple concurrence on pregnancy intendedness* | |

| Both wanted the pregnancy (251) | 3.6 |

| Other situations (41) | 14.6 |

| p = .01 | |

| Concurrence on contraception (before pregnancy)* | |

| Decided together (242) | 3.7 |

| Did not decide together (49) | 12.2 |

| p = .025 | |

| Felt ready when resuming sex after birth | |

| Yes (232) | 3.9 |

| No (44) | 11.4 |

| p = .05 | |

| Father plays with the baby | |

| A lot (160) | 5.0 |

| Fairly (104) | 2.9 |

| A little (25) | 16.0 |

| p = .03 | |

| Woman’s evaluation of the couple relationship | |

| Very good (143) | 2.1 |

| Good (106) | 4.7 |

| Not good (39) | 17.9 |

| p = .0001 | |

| Violence | |

| Present partner violence | |

| No (275) | 4.0 |

| Yes (15) | 26.7 |

| p = .005 | |

| Present family violence | |

| No (274) | 3.6 |

| Yes (17) | 29.4 |

| p = .001 | |

| Any present violence | |

| No (262) | 2.7 |

| Yes (29) | 27.6 |

| p < .001 | |

| Family violence in childhood | |

| No (264) | 4.2 |

| Yes (28) | 14.3 |

| p = .04 | |

Asked in the first questionnaire.

Reporting current violence from the partner was associated with psychological distress: 26.7% of abused women had high GHQ scores vs. 4.0% of those not declaring abuse (p = .005). Women also were more distressed when they reported present family violence (29.4% vs. 3.6%, p = .001) or a history of past childhood family violence (14.2% vs. 4.2%, p = .04). The variable combining present partner or family violence was strongly associated with women’s distress (27.6% vs. 2.7%, p < .001).

Multivariate Analyses

We examined the effect of present and past violence on mothers’ psychological distress, controlling for the other potentially intervening factors: couple relationship, financial problems, work, baby’s hospitalization, and previous depression (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis of Present and Past Violence on Mothers’ Psychological Distress 8 Months After Birth, Controlling for Other Key Determinants (n = 291)

| Odds Ratios (Exp(B)) for GHQ > 5 After Adjustment for Covariates (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|

| Any partner or family violence since the birth | |

| Nor | 1.00 |

| Yes | 13.74** (2.69–70.34) |

| Any family violence in childhood | |

| Nor | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.10 (0.17–6.97) |

| Couple concurrence on the pregnancy | |

| Both wanted the pregnancyr | 1.00 |

| Other situations | 13.39** (2.17–82.61) |

| Economic problems | |

| Nor | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.28 (0.25–6.45) |

| Woman’s satisfaction with current employment situation | |

| Satisfiedr | 1.00 |

| Dissatisfied | 11.85** (2.31–60.71) |

| Hospitalization of the baby | |

| Nor | 1.00 |

| Yes | 15.71** (2.73–90.50) |

| Frequent feelings of anxiety/depression before pregnancy | |

| Nor | 1.00 |

| Yes | 11.28** (2.26–56.26) |

Reference group.

p < .01.

As a measure of violence, we used the synthetic variable combining present partner and family violence, as there was an overlap between these two variables. As an indicator of the couple relationship, we chose the variable measuring concurrence on pregnancy intendedness, because it was collected in the first questionnaire, and thus the direction of the relationship with postpartum distress is clearer.

After adjusting for the other determinants of maternal distress in the model, present violence by a partner or by family member was found to be strongly related to having a GHQ score >5 (adjusted OR = 13.74), while the relationship between past family violence and distress was no longer statistically significant.

Lack of couple concurrence on the pregnancy also was associated with significantly greater adjusted odds of high GHQ scores (adjusted OR = 13.39), as was the woman’s dissatisfaction with her current work situation (adjusted OR = 11.85), the baby having been hospitalized (adjusted OR = 15.71), and women’s prepregnancy mental health (adjusted OR = 11.28). Results were unchanged using the woman’s postpartum evaluation of the couple relationship instead of concurrence on the pregnancy, and when including parity as a covariate.

The relationship between postpartum psychological distress and finan-cial problems is no longer statistically significant in the full logistic regression model. Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the hypothesis that this result, as well as the lack of association with past family violence in the multivariate model, represent cases of mediation.

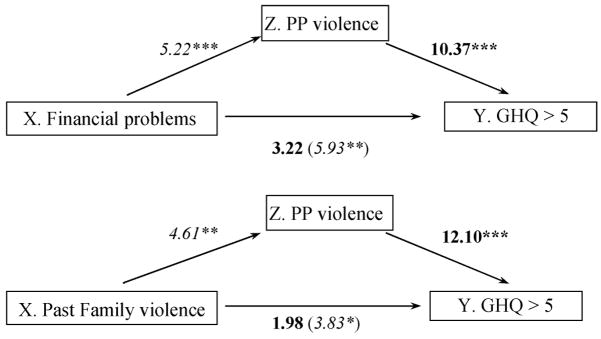

Mediation Analyses

Mediation models are used to examine how an independent variable affects an intermediate outcome (or mediator), which in turn leads to the final outcome (Huang, Sivaganesan, Succop, & Goodman, 2004). For both financial problems and past family violence, the conditions for mediation are met and the odds ratio for the variable is reduced and nonsignificant after controlling for experience of violence after the birth (see Figure 1). These analyses indicate that the effects of financial problems and family violence in the past may, at least partially, work through current violence to affect women’s postpartum mental health.

FIGURE 1.

Mediation analyses. Numbers in italics are odds ratios (with stars indicating significance levels of *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001) from bivariate logistic regression models, showing that the variables of interest (labeled as X) meet the first two conditions for mediation. Numbers in bold are adjusted odds ratios from multivariate logistic regression models showing that the odds ratios for the variables of interest are reduced and non significant when the mediator (labeled as Z) is also included in the model.

In order to obtain estimates of the indirect effects of these variables on postpartum depression, we conducted a path analysis using probit regression using the Mplus program (version 4.0). Bias-corrected 95% and 99% confidence intervals for the indirect effects were computed via the bootstrap based on 5,000 bootstrap replications (Mackinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). For financial problems, this analysis revealed that the indirect effect of financial problems through postpartum violence on psychological distress was significant at the .01 level (probit regression coefficient = 0.696, 99% CI: 0.054–2.118), while the indirect effect of past family violence through postpartum violence on postpartum distress was significant at the .05 level (regression coefficient = 0.686, 95% CI: 0.159–1.663). According to these analyses, the probability of experiencing postpartum distress is increased by 5.6% for individuals who experience financial problems when this relationship is mediated by having experienced violence during the postpartum period. In the case of past family violence, the probability of experiencing postpartum distress is increased by 6.1% for individuals who experienced past family violence when this relationship is mediated by having experienced violence during the postpartum period.

The probit regression results indicate that probability of psychological distress ranges from around 1% for women without these factors, to 10.7% for women with both past family violence and violence since the birth, and to 13.7% for those with both financial problems and violence since the birth.

DISCUSSION

In this socially stable Italian sample, 5% of the women experienced partner violence since the birth, and 6% by another family member. Ten percent reported violence either by a partner, another relative, or both, most of this violence being psychological. Moreover, 9.5% of women reported a history of family violence during childhood.

As there are very few studies on violence during the postpartum period, and investigators have used different instruments to evaluate violence, comparison of our results with other studies is difficult. In the first year postpartum, 4% of women in a French study reported partner violence (Saurel-Cubizolles et al., 1997), and in a nationwide Swedish sample, 2% of women said they had been hit by a male partner during the same time period (Radestad et al., 2004). This latter result is similar to the 2% of women who had experienced physical violence—including threats, physical or sexual aggressions—found in our study. Higher rates of partner violence (psychological, physical, or sexual) in the year following a birth have been found by other researchers, for example, 8.3%, in a sample of Chinese women (Guo et al., 2004). In a study in the United States involving a socially disadvantaged sample of women, researchers found even higher rates of violence in the 6 months after birth: 19% of mothers experienced “moderate to severe” violence by a male partner, and 10% by another relative (Gielen et al., 1994).

In our study, 5% of women showed high psychological distress 8 months after childbirth. Again, comparisons with other studies are difficult, because we used an instrument designed to measure psychological distress in the general population, the GHQ, instead of a more specific instrument such the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). We chose the GHQ in order to be able to compare our results with those of the very few studies on new mothers’ depression and on the impact of violence on women’s mental health carried out in Italy (Romito et al., 1999, 2005). While the use of different instruments makes strict comparison impossible, the 5% rate of mothers with high psychological distress found in our study is similar to the rates found in other European studies using the EPDS, such as 4.5% of women scoring high (12 or more) on the EPDS 2–3 months postpartum in Sweden (Wickberg & Hwang, 1997), and the 5.5% of women classified as “depressed” 4 months postpartum in Denmark (Nielsen Forman, Videbech, Hedegaard, Dalby Salvig, & Secher, 2000).

The strongest associations in the current study were between present violence and mothers’ psychological distress: rates of high GHQ scores went from around 4% in women without these types of violence to 26% for those experiencing partner and 29% for those experiencing family violence. The few other investigators who have considered this issue also found significant associations between current violence and the woman’s mental health in the postpartum period (Leung et al., 2002; Saurel-Cubizolles et al., 1997). As in other studies (Gielen et al., 1994; Leung et al., 2002), women in our sample reported violence by both male partners and other family members. Similar to the Chinese study, we found an effect of relatives’ violence (which was exclusively psychological) on women’s mental health. Moreover, as in other studies, having experienced family violence in childhood was also significantly associated with maternal distress in the postpartum-period (Lang et al., 2006). Health professionals, when discussing violence with new mothers, should carefully consider also psychological violence and violence perpetrated by relatives other than the partner, both in the present and in the past.

Our bivariate results confirm the importance of other psychosocial factors—financial difficulties, problems with women’s work and with partner relationship, the baby’s health, and the woman’s previous mental health—in the mother’s current psychological distress, while there were no associations with demographic factors, nor with factors linked to the type of childbirth, contraception, and breast-feeding. Having experienced anxiety and depression before pregnancy also was associated with postpartum psychological distress.

Work may play an important role in mothers’ well-being in this cultural setting. In our sample, problems concerning work and the discrepancy between desired and actual employment status were significantly associated with depressive symptoms, a trend shown by other researchers. The most distressed women are always those who would prefer to be employed but are at home (Romito et al., 1999). These results underscore the importance of women’s individual differences as well as the importance of paid work, also in the postpartum period. It seems that policy measures—such as adequate maternity leave and high-quality childcare provisions—that make it possible for new mothers to work under good conditions may improve women’s psychological health as well as the well-being of their families.

Other investigators have found that marital difficulties are strongly related to depression in women in the postpartum period (Eberhard-Gran, Eskild, Tambs, Samuelsen, & Opjordsmoen, 2002). Romito and colleagues (1999) carried out a study in France and Italy. Results from their multivariate analyses showed that, when the relationship was evaluated as “not good,” the risk of depression was about five times higher than when it was evaluated as “very good”; mothers without a current partner were less likely to be depressed than those declaring a difficult relationship. In the present study, all the indicators of the couple relationship were strongly associated with women’s distress 8 months postpartum; two of them—couple concurrence on contraception and on pregnancy intendedness—were collected at the time of the first questionnaire. Concurrence on pregnancy intendedness seems to be a key indicator of problems in the couple, for researchers in various countries found that it is strongly associated with partner violence against women during pregnancy (Leung et al., 2002; Pallitto & O’Campo, 2004; Purwar, Jeyaseelan, Varhadpande, Motghare, & Pimplakute, 1999; Saltzman et al., 2003). In one U.S. study, women with an unwanted/mistimed pregnancy accounted for 70% of women with violence (Gazmararian et al., 1995).

When the baby had been hospitalized during the 8 months after the birth, mothers also experienced more psychological distress. Some authors seem to take for granted that baby’s health problems and a higher frequency of hospital admissions are a consequence of postnatal depression (Nielsen Forman et al., 2000). Our data, showing associations between baby’s birth weight and subsequent hospital admissions, suggest that mothers may become distressed because their baby is unwell.

Most of the bivariate results were confirmed in the multivariate analyses. The risk of reporting high depression scores was 13 times higher when women were experiencing partner or family violence, and when there had been disagreement in the couple concerning the pregnancy. This underlines both the role of violence in women’s mental health and the fact that the quality of couple relationship is also an important determinant by itself, even in the absence of physical or psychological violence. Women dissatisfied with their working status had an adjusted odds ratio of psychological distress of 11.85, taking into account the other psychosocial variables. We found that the baby’s hospital admission increased by 15 times the risk of mothers’ psychological distress. The occurrence of anxiety or depression previous to the pregnancy was also independently associated with postpartum depression. On the contrary, economic problems and family violence in the past became nonsignificant after their inclusion in the multivariate analyses. In both cases, we constructed path analytic models that indicate a mediating role for present violence. Financial problems may contribute to partner or family violence during the postpartum period, and the violence, in turn, may lead to postpartum depression. Similarly, in the case of family violence in the past, the mediation model indicates that past family violence is related to current (postpartum) violence, and then the current violence leads to women’s feelings of depression after the birth. These exploratory analyses are indicative of the key importance of preventing violence for women’s mental health as well as illustrating how some specific factors may work together to compound the risk of depression in the postpartum period.

The study has a number of limitations. Non-Italian women are under-represented, and thus our results that show no associations between nationality and mental health should be considered with caution. Other researchers have found that newly immigrant women have a higher risk of becoming depressed after the birth of a baby (Dennis et al., 2004; Glasser et al., 1998). Another limitation concerns the measurement of women’s mental health. In order to compare our results with those of the few other Italian studies, we used the GHQ, which is a self-report instrument of psychological distress widely utilized with women in the perinatal period (Gavin et al., 2005), but it is not specifically constructed to measure postpartum depression. On the other hand, the sample is likely to be fairly representative of Italian women giving birth in Trieste, as the study took place in the only maternity hospital in the city and had a good response rate. Other strengths of the study reside in the measurement of our indicators: we asked detailed questions on current partner and family violence, and we also have measures of childhood family violence; we have multiple indicators of women’s work situations and of the quality of the couple relationship. Concerning the latter, we also have information collected in the first questionnaire. Moreover, our study is unique in that we demonstrated the impact of current violence, after controlling for other well-known risk factors of depression in the postpartum period, such as financial difficulties, work dissatisfaction, an unsatisfactory couple relationship, a baby who was hospitalized, and women’s previous mental health.

CONCLUSIONS

In this Italian sample of new mothers, 10% were experiencing violence by their male partner or by another family member, and 5.1% showed high psychological distress. This violence strongly affected women’s psychological well-being, independently from other known risk factors for depression.

New mothers’ mental health has been a serious concern for health workers for some decades, as women’s depression at this time, besides being painful for her, can also negatively affect the child’s psychological development (Murray & Cooper, 1997). To prevent and treat mothers’ depression and its effects, a number of intervention programs have been developed and carefully evaluated, but these interventions do not appear to be effective in most cases (Dennis, 2005). It is possible that they are not successful because they are too generic and do not address women’s more urgent problems, such as violence (Wiggins et al., 2005).

Recently, researchers have shown that if health workers are competent and sensitive to the women’s needs, women do not mind being asked about violence in the postpartum period, and that, as a consequence of the screening process, some may usefully be referred to other agencies and get help (Matthey et al., 2004; Radestad et al., 2004; Stenson, Saarinen, Heimer, & Sidenvall, 2001; Ulrich et al., 2006). The present study, in which we demonstrate both the frequency of violence and its heavy toll on new mothers’ mental health, is another indication of the necessity of addressing the role of violence in women’s lives, including the postpartum period.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a grant from the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura Burlo Garofolo, Trieste. Janet Molzan Turan’s work on this article was also supported, in part, by grant # T32 MH-19105-17 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Contributor Information

PATRIZIA ROMITO, Department of Psychology, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy.

JANET MOLZAN TURAN, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

TORSTEN NEILANDS, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

CHIARA LUCCHETTA, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy.

LAURA POMICINO, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy.

FEDERICA SCRIMIN, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy.

References

- Aslig-Monemi K, Pena R, Ellsberg MC, Persson LA. Violence against women increases the risk of infant and child mortality. A case-referent study in Nicaragua. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81(1):10–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billari FC, Kohler HP. Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies. 2004;58:161–176. doi: 10.1080/0032472042000213695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Garcia-Moreno C, Sharps P. Abuse during pregnancy in industrialized and developing countries. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:770–789. [Google Scholar]

- Coker A, Sanderson M, Dong B. Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Paediatric & Perinatal Epidemiology. 2004;18:260–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for prevention of postnatal depression: Systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2005;331(7507):15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7507.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, Janssen PA, Singer J. Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period. Acta Psychiatria Scandinavica. 2004;110:338–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Rivieres-Pigeon C, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Romito P. Psychological distress one year after childbirth: A cross-cultural comparison between France, Italy and Quebec. European Journal of Public Health. 2003;13:218–225. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Samuelsen S, Opjordsmoen S. Depression in postpartum and non-postpartum women: Prevalence and risk factors. Acta Psychiatria Scandinavica. 2002;106:426–433. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D, Horwood J, Lynskey M. Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behavior and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21:789–803. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian JA, Adams MM, Saltzman LE, Johnson CH, Bruce FC, Marks JS, et al. The relationship between pregnancy intendedness and physical violence in mothers of newborns. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1995;85:1031–1037. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, O’Campo PJ, Faden RR, Kass NE, Xue X. Interpersonal conflict and physical violence during the childbearing year. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;39:781–787. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser S, Barell V, Shoham A, Ziv A, Boyko V, Lusky A, et al. Prospective study of postpartum depression in an Israeli cohort: Prevalence, incidence and demographic risk factors. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;19(3):155–164. doi: 10.3109/01674829809025693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire: A technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, Rutter C. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(1):191–197. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding J. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Guo SF, Wu JL, Qu CY, Yan RY. Domestic abuse on women in China before, during, and after pregnancy. Chinese Medical Journal (Engl) 2004;117:331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Thomas K, AbouZahr C, Walker N, Say L, Inoue M, et al. Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: An assessment of available data. The Lancet. 2007;370:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Sivaganesan S, Succop P, Goodman E. Statistical assessment of mediational effects for logistic mediational models. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:2713–2728. doi: 10.1002/sim.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Italian Health Ministry. Recommendations to prevent maternal mortality associated to labor and childbirth. Raccomandazioni per la prevenzione della morte materna correlata al travaglio e/o parto. 2007 Retrieved February 23, 2008, from http://www.ministerosalute.it/imgs/C17pubblicazioni629allegato.pdf.

- Kitzmann K, Gaylord N, Holt A, Kenny E. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review 2003. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss M, Bailey J, Yuan N, Herrera V, Lichter E. Depression and PTSD in survivors of male violence: Research and training initiatives to facilitate recovery. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lang A, Rodgers C, Lebeck M. Associations between maternal childhood maltreatment and psychopathology and aggression during pregnancy and postpartum. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung WC, Kung F, Lam J, Leung TW, Ho PC. Domestic violence and postnatal depression in a Chinese community. International Journal of Gynaecolgy and Obstetrics. 2002;79:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Li Y, Casanueva C, Harris-Britt A, Kupper LL, Cloutier S. Intimate partner violence and women’s depression before and during pregnancy. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:221–239. doi: 10.1177/1077801205285106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez R, Johnston-Robled I, Ulsh H, Chrisler J. Singing “The Baby Blues”: A content analysis of popular press articles about postpartum affective disturbances. Women’s Health. 2000;31(23):37–56. doi: 10.1300/j013v31n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S, Phillips J, White T, Glossop P, Hopper U, Panasetis P, et al. Routine psychosocial assessment of women in the antenatal period: Frequency of risk factors and implications for clinical services. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2004;7:223–229. doi: 10.1007/s00737-004-0064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CC, Schei B, Myhr TL, Du Mont J. Abuse: A risk factor for low birth weight? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2001;164:1567–1572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Cooper PJ. Postpartum depression and child development. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:253–260. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyer G. Family change and family policies in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen Forman D, Videbech P, Hedegaard M, Dalby Salvig J, Secher NJ. Postpartum depression: Identification of women at risk. BJOG. 2000;107:1210–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallitto CC, O’Campo P. The relationship between intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy: Analysis of a national sample from Colombia. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2004;30(4):165–173. doi: 10.1363/3016504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnelli A, Racioppi F, Terzera L. Genere, famiglia e salute [Gender, family and health] Milano: Angeli; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Purwar MB, Jeyaseelan L, Varhadpande U, Motghare V, Pimplakute S. Survey of physical abuse during pregnancy GMCH, Nagpur, India. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecological Research. 1999;25:165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1999.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radestad I, Rubertsson C, Ebeling M, Hildingsson I. What factors in early pregnancy indicate that the mother will be hit by her partner during the year after childbirth? A nationwide Swedish Survey. Birth. 2004;31(2):84–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romito P, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Lelong N. What makes new mothers unhappy: Psychological distress one year after birth in Italy and France. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49:1651–1661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romito P, Turan JM, De Marchi M. The impact of current and past interpersonal violence on women’s mental health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:1717–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman LE, Johnson CH, Colley Gibert B, Goodwin MM. Physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: An examination of prevalence and risk factors in 16 states. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2003;7(1):31–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1022589501039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Blondel B, Lelong N, Romito P. Violences conjugales aprés une naissance [Marital violence after birth] Contraception, Fertilité, Sexualité. 1997;25(2):159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Lelong N. Violences familiales pendant la grossesse [Family violence during pregnancy] Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics & Biological Reproduction. 2005;34:2S47–2S53. doi: 10.1016/s0368-2315(05)82687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Romito P, Ancel PY, Lelong N. Unemployment and psychological distress one year after childbirth in France. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2000;54:185–191. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenson K, Saarinen H, Heimer G, Sidenvall B. Women’s attitudes to being asked about exposure to violence. Midwifery. 2001;17:2–10. doi: 10.1054/midw.2000.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich CY, McKenna SL, King C, Campbell D, Ryan J, Torres S, et al. Postpartum mothers’ disclosure of abuse, role, and conflict. Health Care for Women International. 2006;27:324–343. doi: 10.1080/07399330500511733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickberg B, Hwang CP. Screening for postnatal depression in a population-based Swedish sample. Acta Psychiatria Scandinavica. 1997;95:62–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins M, Oakley A, Roberts I, Turner H, Rajan L, Austerberry H, et al. Postnatal support for mothers living in disadvantaged inner city areas: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005;59:288–295. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.021808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Violence against women. Women’s Health and Development Programme. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 1997. [Google Scholar]