Abstract

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus endemic to northwestern Ontario, Manitoba and some parts of the United States. The fungus is also endemic to parts of Africa. Pulmonary and extrapulmonary findings of a 24-year-old African man who presented with weight loss, dry cough and chronic pneumonia not resolving with antibiotic treatment are presented. The unusual occurrence of pulmonary blastomycosis associated with skin lesions and a moderate pleural effusion is reported.

Keywords: Blastomyces dermatitidis, Pleural effusions, Skin ulcers

Abstract

Blastomyces dermatitidis est un champignon dimorphe, endémique dans le Nord-Ouest de l’Ontario, au Manitoba et dans certaines régions des États-Unis, de même que dans certaines régions de l’Afrique. Voici l’histoire de la maladie d’un Africain âgé de 24 ans, qui a consulté pour une perte de poids, une toux sèche et une pneumonie chronique, résistante au traitement antibiotique, ainsi que les résultats d’examens pulmonaires et extrapulmonaires. Il sera question, dans le présent article, d’un cas plutôt rare de blastomycose pulmonaire, associée à des lésions cutanées et à un épanchement pleural modéré.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 24-year-old previously healthy man from Tanzania presented with a three-month history of dry cough, fatigue and fever. He was treated empirically for a community-acquired pneumonia; however, after two courses of antibiotic treatment he did not improve clinically, and had a worsening chest radiograph showing a large unilateral pleural effusion. His vital signs, however, were normal. Other clinical features included a 14 kg weight loss and scaling papulonodular skin lesions on the nose (Figure 1A), right hand (Figure 1B) and right forearm. In addition to the skin lesions, he also had a raised subcutaneous nodular lesion on his left buttock and left upper arm suppuration.

Figure 1).

Scaling papulonodular skin lesions on the nose (A) and right hand (B)

Investigations

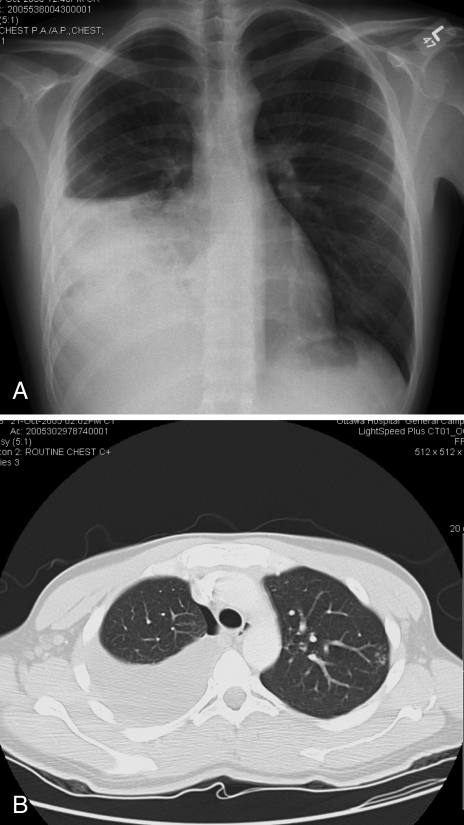

On admission, the patient’s white blood cell count was 13.5×109/L, hemoglobin level was 117 g/L, platelet count was 584×109/L and serum albumin level was 30 g/L. Electrolytes, renal function and liver enzyme levels were normal. HIV serology was negative. Sputum initially showed heavy growth of normal respiratory flora; no acid-fast bacilli were seen. A pigtail catheter was inserted to drain the right pleural fluid which showed a pH of 8, glucose level of 5.6 mmol/L, total protein concentration of 62 g/L and lactate dehydrogenase level of 152 U/L. Pleural fluid white blood cell differential showed 31% neutrophils, 61% lymphocytes, 7% monocytes and 1% eosinophils. The pleural fluid was consistent with an exudate. Bronchoscopy washings were negative for Gram and fungal stains. Radiographs of the pelvis and femur were normal. A plain chest radiograph showed a moderate-sized right pleural effusion on posteroanterior view (Figure 2A) and some ill-defined soft tissue nodules in the lateral aspect of the left upper lung zone. An enhanced axial computed tomography of the thorax in the mediastinal window settings confirmed a moderate-sized right pleural effusion with multiple well-defined soft tissue nodules over the parietal pleura projecting into the pleural cavity, which was better seen over the diaphragmatic surface (Figure 2B). No significant mediastinal lymphadenopathy was noted. On the lung window settings, centrilobular nodules in a tree-in-bud pattern at the apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe were present. Consolidative changes of the lateral segment of the right middle lobe and the right lower lobe were also seen.

Figure 2).

A A plain chest radiograph showing a moderate-sized right pleural effusion; B Computed tomography of the thorax in the lung window settings confirmed a moderate-sized right pleural effusion. Consolidative changes of the lateral segment of right middle lobe and right lower lobe were also seen. A small pneumothorax was seen following a thoracentesis. Centrilobular nodules in a tree-in-bud pattern at the apicoposterior segment of left upper lobe were present

Hospital course

The patient was from an area endemic for HIV and tuberculosis, and had significant weight loss, mild anemia, mild hypoal-buminemia and high lymphocytes in the pleural fluid. Apart from not responding to antibiotics for a community-acquired pneumonia, he was an otherwise healthy young African man. Before diagnosis, he was isolated and started on standard tuberculosis treatment empirically for four days, after which the treatment was discontinued.

Diagnosis

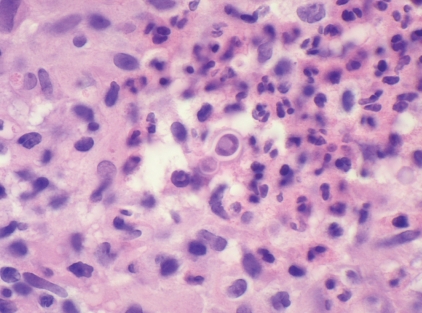

Definitive diagnosis of blastomycosis requires the growth of the fungus from a clinical specimen; however, a presumptive diagnosis may be made by direct histological visualization of a characteristic yeast with broad-based budding (1). A punch biopsy of the right hand of our patient showed a thick layer of compact hyper- and parakeratosis on the surface associated with somewhat irregular pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia, and beneath this a mixed inflammatory reaction with large numbers of neutrophils mixed with multinucleated and epithelioid histiocytes. A periodic acid-Schiff stain confirmed the presence of large fungal spores. One spore with broad-based budding was identified and was consistent with Blastomyces dermatitidis (Figure 3). Serological tests are generally not helpful for diagnosing blastomycosis (1). A positive titre should not be taken as an indication to begin treatment, and a serological test should never be used to rule out the disease (1). Later in the course of the infection, the sputum, bronchial washings and skin biopsies grew Blastomycosis dermatitidis.

Figure 3).

High power magnification of a skin biopsy showing a spore measuring approximately 15 microns in diameter and showing broad-based budding in a background of neutrophils and histiocytes

Treatment

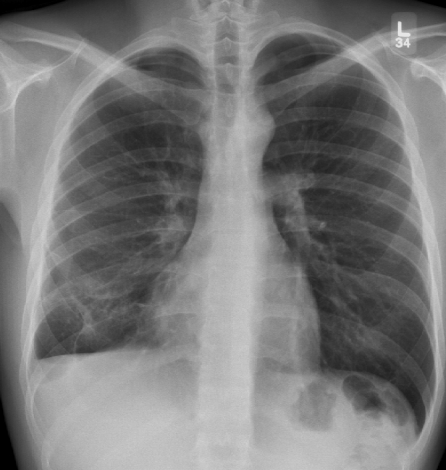

Patients who have disseminated blastomycosis disease require treatment. The patient was treated with oral itraconazole 200 mg daily for six months. Two weeks following treatment, the nasal skin lesion almost disappeared, and the pleural effusion almost completely resolved after three months (Figure 4). Amphotericin was not used because it is normally reserved for patients who have central nervous system involvement or patients with life-threatening disease (1).

Figure 4).

Plain chest radiograph showing the resolution of the right pleural effusion following three months of itraconazole treatment. Blunting of the costophrenic angle is seen

DISCUSSION

In Canada, B dermatitidis is endemic to northwestern Ontario and Manitoba, comparable with the highest rates known in North America (2). The incidence of disease is higher in First Nations reserves than in urbanized areas. Since June 2000, cases of blastomycosis have been reported in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario (3). One of the main risk factors identified for acquisition of the fungus by humans is waterway recreational activities (2). The fungus usually resides in the soil in wooded areas near rivers and lakes. Several severe cases have been recently reported in northern Ontario from patients visiting lakeside cottages (4). Our patient had not gone camping, visited areas next to waterways or visited any cottages.

B dermatitidis can produce a variety of clinical syndromes, from an asymptomatic infection to fulminant acute respiratory distress syndrome (5). Our patient presented with a chronic, progressive, respiratory illness with a symptom constellation that resembled tuberculosis. However, the skin lesions were not typical of skin lesions normally seen in tuberculosis. B dermatitidis commonly infects the lung through inhalation of conidia, and then disseminates to extrapulmonary sites including the skin, bones and the genitourinary organs (6). Several case studies have reported on direct cutaneous inoculation of blastomycosis (7). Most inoculations were due to laboratory staff coming in direct contact with a specimen (50%) or as a result of an animal bite, usually from dogs, who are important reservoirs of the disease. Our patient did not work in a laboratory and had not been bitten or been in contact with any dogs or any other animals. The patient was most likely infected through inhalation of blastomycosis which then disseminated and caused metastatic skin lesions.

Blastomycosis is also endemic to parts of Africa (5). Our patient is from Tanzania and had been in Canada for the past five years. In the largest review of known cases of B dermatitidis in Africa (8), 18 countries reported a total of 81 cases, one of which was from Tanzania. Although the existence of endogenous reactivation of blastomycosis is not universally accepted, a few cases have been reported (9,10). Our patient may have been infected in Africa which resolved spontaneously and then reactivated while in Canada. In a review by Carman et al (8), 81 cases of blastomycosis that occurred in Africa over a period of 35 years were studied. Morphological differences between isolates of B dermatitidis exist; however, these differences often overlap and do not allow us to make a clear distinction between the African and North American strains. Furthermore, other groups have failed to find genotypic differences between the two strains. More study is required before conclusions may be made on genetic differences between the two strains (11). Clinical differences between the African and North American isolates were noted. The African isolate presents with different types of skin lesions, less frequently involves the central nervous system and more frequently involves bone (8). Skin lesions associated with the African strain usually present as ulcers or subcutaneous abscesses that have broken through the epidermal surface (8). Our patient had raised ulcers (Figures 1A and 1B) and subcutaneous abscesses that drained spontaneously and disappeared following therapy. For the detection of osteomyelitis, our patient had radiographs performed of the pelvis, femur and humerus, but the results were negative. Pleural effusions are rare in both African and North American strains of blastomycosis. Only two cases of pleural effusion among African patients have been described (8,12).

A large pleural effusion due to blastomycosis is an uncommon manifestation of the disease (13,14). Only two other cases of a pleural effusion due to blastomycosis have been described in African patients (8,15). Empyema was the initial presentation in a case report from the United States (16). Cytological examination of pleural fluid may help in the diagnosis of pleural effusion secondary to blastomycosis (17,18). In our case, blastomycosis did eventually grow from a culture taken from the pleural fluid but the initial diagnosis was made from the skin biopsy of the right hand lesion (Figure 1B).

CONCLUSIONS

A chronic respiratory illness associated with weight loss, anemia and a large pleural effusion in a young African man should prompt the clinician to diagnose and manage pulmonary tuberculosis; however, other etiologies can exist. Although large pleural effusions are not a classic presentation for pulmonary blastomycosis, skin manifestations may aid in building a differential diagnosis. In addition, although blasto-mycosis is endemic to Manitoba and northwestern Ontario, it can occur elsewhere and endemic mycoses should remain on the differential diagnosis of chronic pneumonia despite the demographic risks for tuberculosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chapman SW, Bradsher RW, Jr, Campbell GD, Jr, Pappas PG, Kauffman CA. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:679–83. doi: 10.1086/313750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwight PJ, Naus M, Sarsfield P, Limerick B. An outbreak of human blastomycosis: The epidemiology of blastomycosis in the Kenora catchment region of Ontario, Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2000;26:82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crampton TL, Light RB, Berg GM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1310–6. doi: 10.1086/340049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmar MS. Paradise – not without its plagues: Overwhelming Blastomycosis pneumonia after visit to lakeside cottages in Northeastern Ontario. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies SF, Sarosi GA. Epidemiological and clinical features of pulmonary blastomycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:206–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradsher RW. Clinical features of blastomycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44–9. doi: 10.1086/339957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carman WF, Frean JA, Crewe-Brown HH, Culligan GA, Young CN. Blastomycosis in Africa. A review of known cases diagnosed between 1951 and 1987. Mycopathologia. 1989;107:25–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00437587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehni W. Endogenous reactivation in blastomycosis. Am J Med. 1989;86:831–2. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laskey W, Sarosi GA. Endogenous activation in blastomycosis. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:50–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-1-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCullough MJ, DiSalvo AF, Clemons KV, Park P, Stevens DA. Molecular epidemiology of Blastomyces dermatitidis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:328–35. doi: 10.1086/313649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logsdon MT, Jones HE. North American blastomycosis: A review. Cutis. 1979;24:524–7. 32–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jay SJ, O’Neill RP, Goodman N, Penman R. Pleural effusion: A rare manifestation of acute pulmonary blastomycosis. Am J Med Sci. 1977;274:325–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Failla PJ, Cerise FP, Karam GH, Summer WR. Blastomycosis: Pulmonary and pleural manifestations. South Med J. 1995;88:405–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibrahim TM, Edinol ST. Pleural effusion from blastomycetes in an adult Nigerian: A case report. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2001;8:148–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiesman IM, Podbielski FJ, Hernan MJ, Sekosan M, Vigneswaran WT. Thoracic blastomycosis and empyema. JSLS. 1999;3:75–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covell JL, Lowry EH, Jr, Feldman PS. Cytologic diagnosis of blastomycosis in pleural fluid. Acta Cytol. 1982;26:833–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hargis JL, Bone RC, Miller FC, Wilson FJ. Pulmonary blastomycosis diagnosed by thoracocentesis. Chest. 1980;77:455. doi: 10.1378/chest.77.3.455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]