Abstract

Purpose

To determine if gene expression signature of invasive oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) can sub-classify OSCC on the basis of survival.

Experimental Design

We analyzed the expression of 131 genes in 119 OSCC, 35 normal and 17 dysplastic mucosae to identify cluster-defined sub-groups. Multivariate Cox regression was used to estimate the association between gene expression and survival. By stepwise Cox regression the top predictive models of OSCC-specific survival were determined, and compared by Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis.

Results

The 3-year overall mean survival (± SE) for a cluster of 45 OSCC patients was 38.7 ± 0.09%, compared to 69.1 ± 0.08% for the remaining patients. Multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex and stage showed that the 45 OSCC cluster patients had worse overall and OSCC-specific survival (HR=3.31, 95% CI: 1.66, 6.58; HR=5.43, 95% CI: 2.32, 12.73, respectively). Stepwise Cox regression on the 131 probe sets revealed that a model with a term for LAMC2 (laminin, gamma 2) gene expression best identified patients with worst OSCC-specific survival. We fit a Cox model with a term for a principal component analysis-derived risk-score marker (‘PCA’) and two other models that combined stage with either LAMC2 or PCA. The Area Under the Curve for models combining stage with either LAMC2 or PCA was 0.80 or 0.82, respectively, compared to 0.70 for stage alone (p=0.013 and 0.008, respectively).

Conclusions

Gene expression and stage combined predict survival of OSCC patients better than stage alone.

Introduction

Although advances in surgical techniques and the use of adjuvant treatment modalities have led to some site-specific improvements in survival of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), the overall prognosis for advanced stage disease has not improved significantly in the past two decades (1). One of the impediments to the effective management of OSCC patients is our limited ability to predict the natural history of individual lesions. Unfortunately, the current head and neck cancer staging system is inadequate for predicting survival outcomes, and there seems to be significant clinical and molecular heterogeneity within stages (2)(3). However, to date, there are no molecular markers that are used clinically to stratify OSCC and other head and neck cancer patients. Recently, many studies have utilized high-throughput microarray technology in an attempt to identify the different genetic pathways involved in the carcinogenic process and to relate gene expression signatures to clinical outcomes (4)(5)(6)(7). Gene expression profiling of OSCC would be most useful if it could add to our existing staging system to predict clinical outcomes more accurately, yet no studies to date have addressed this question.

We recently identified 131 probe sets (corresponding to 108 known genes) which were differentially expressed between OSCC and normal oral mucosa (8). In this paper, hierarchical clustering and principal component analyses of OSCC, dysplasia and normal oral mucosa using these 131 probe sets revealed that oral dysplasias appear to have varied expression patterns such that some clustered with OSCC and others with normal oral mucosae. We then tested the hypothesis that there might be a spectrum of oral carcinogenesis on the basis of these 131 probe sets, and that OSCC that are least ‘dysplasia-like’ in gene expression are those that are further along in the carcinogenic process and, thus, are associated with worse survival.

Materials and Methods

Study population

As described in Chen et al., we identified English-speaking patients 18 year of age or older with a first, primary OSCC or dysplasia undergoing surgery or biopsy between December 16th, 2003 and April 17th, 2007 at one of the three University of Washington-affiliated hospitals: University of Washington Medical Center, Harborview Medical Center and the Puget Sound Veterans Affairs Health Care System (VA). Eligible controls were patients who were scheduled to undergo surgery of the oral cavity or oropharynx for non-cancer treatment, such as tonsillectomy or sleep apnea, at the aforementioned institutions during the same time period the cases were recruited. All patients recruited to the study were interviewed in person using a structured lifestyle and medical history questionnaire. Data regarding tumor characteristics, such as stage, were abstracted from medical records. Comorbidity scores were calculated using Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 Test (9)(10). Patients were followed actively through phone contact and passively through review of medical records and linkage to the U.S. Social Security Death Index. If a patient had died, we classified the death as due to OSCC or not due to OSCC based on review of medical records and death certificates. All participants gave informed consent, and all study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, University of Washington, and the VA.

Of the 187 OSCC patients we recruited, we had Affymetrix U133 2.0 Plus array data that had passed our quality control criteria and at least 4 months of follow-up time for 150 patients. The requirement for our study participants to have at least 4 months follow-up refers to the starting point at which we would began to capture events. This was done because we did not want to include any events until participants had completed treatment to avoid capturing deaths from patients who died due to co-morbidities rather than tumor biology. We also included array results from 17 dysplasias (11 dysplasia patients and an additional six dysplastic lesions from five OSCC patients. Out of these five OSCC patients, only one invasive tumor tissue was included among the 150 OSCC cases) and 35 normal oral mucosa from controls. All samples were collected, processed, and hybridized onto Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0 oligonucletoide arrays as described in Chen et al (8). In addition, all cases were typed for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) using the LINEAR ARRAY HPV Genotyping Test (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) containing complementary sequences to the PCR products for 37 HPV genotypes (including the 13 “high risk” genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) under a research use only agreement as described in Lohavanichbutr et al (11).

Generation of the 131-probe set list

The 131 probe set list was obtained by comparing the differential gene expression between 119 OSCC cases and 35 normal controls as described in Chen et al (8).

Hierarchical Clustering and Principal Component Analysis

Supervised hierarchical clustering analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) of the expression data from 119 OSCCs and 35 controls used to generate the 131 probe set list in our previous study, plus an additional 17 dysplasias, were performed using GeneSpring GX Software v7.3.1 (Silicone Genetics, CA).

Differential Gene Expression Among OSCC

To identify sub-groups of the 119 OSCC cases based on differential gene expression values from GC Robust Multi-array Average (GCRMA), we used a regression-based approach implemented in GenePlus software (12). For this comparison, we used the number of false discoveries (NFD) as the type I error selection criterion (13). Gene ontology and pathway analysis for the resultant list of genes was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software version 6.

Survival Analysis

Follow-up time for analyses of survival for the 119 OSCC cases was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death, loss-to-follow-up, or April 30, 2007, whichever came first, according to the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences between groups were assessed with the log-rank test. We did not compute OSCC-specific Kaplan Meier survival estimates because of possible informative censoring due to death from other causes. Rather, we estimated OSCC-specific cumulative mortality using methods described by Kalbfleisch and Prentice, which account for competing risk events (14)(15). Cox-proportional hazards regression model was used to estimate overall and OSCC-specific survival associations with cluster-defined OSCC sub-group status, age, sex, stage, HPV status, tumor site, treatment intensity (defined as receiving one, two or all three different treatment modalities (surgery, radiation or chemotherapy)) and co-morbidity score. Dummy variables were created for cluster-defined OSCC sub-group status, stage, sex, HPV status (none vs. positive/low-risk vs. positive/high-risk), tumor size, nodal status, tumor site (oral vs. oropharyngeal) and co-morbidity score. These statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software version 9.2.

Prediction model building for OSCC-specific mortality

For this analysis, we used a total of 150 OSCC cases: 119 cases which had been used to derive the 131 probe sets in our previous study (8), plus an additional 31 cases that were recruited thereafter for which we had vital status information and at least 4 months follow-up. We utilized stepwise Cox-proportional hazards regression based on the 131 probe sets previously found by us to be differentially expressed between OSCC cases and controls (SAS version 9.2) (8). For the stepwise regression, the significance level for both entrance and exit were each set at α=0.01. To obtain the top 10 models, we conducted ten sequential stepwise regression procedures, with each successive procedure eliminating the selected probe set(s) from the previous procedure. Individual risk scores from the top probe set Cox regression model were compared graphically to risk scores from Cox models with terms for the first and second principal components (PC) from PCA of the 131 probe sets, using Matlab version R2006b.

Comparing survival prediction models with TNM stage

To assess whether a survival model which incorporates gene expression data is better than one without it, we used an adapted Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis (16). Risk scores were calculated for 5 models. The first three models contained the terms: ‘stage’; ‘gene(s) from top prediction model’; and ‘PCA’ – a score representing the expression of the entire 131 probe sets as summarized by the combination of the first and second PCs. The other two models combined the term ‘stage’ with either of the other two terms. For each model, we constructed ROC curves for predicting two year all-cause survival. At each level of the model-derived risk score, the nearest 10% (using Nearest Neighbor Estimation) was used to estimate true positive and false positive rates. The survival ROC package*, available for R-project software, was used to implement these methods. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was calculated to quantify the ability of each model to predict two year survival. One thousand bootstrap samples were generated to estimate standard errors and 95% confidence intervals for AUC estimates, and to obtain p-values for testing the null hypothesis that specific gene expression values or PCA do not add to ability of stage to predict survival.

In order to reduce the over-optimism of ROC and AUC estimates due to using the same data both to estimate and assess the predictive ability of risk scores, we performed a jackknife leave-one-out analysis (17). Parameter estimates for the risk model were obtained excluding one subject, and the resulting risk model was used to estimate a risk score based on the excluded subject’s gene expression and/or stage characteristics. This process was repeated until risk scores were assigned to each subject. ROC and AUC estimates were calculated for these jackknife risk scores as they were for the original risk scores.

Validation of LAMC2, OSMR, SERPINE1, OASL, by qRT-PCR

We used qRT-PCR to validate the expression of the four genes found to be related to survival in our top two models. Sixty samples were chosen at random for testing. Each sample was assayed in triplicate in 10 µl reaction volumes using the QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and bioinformatically validated QuantiTect primers (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) on a 7900HT Sequence Detection System (ABI, Foster City, CA). The cycling conditions were as follows: 30 minute incubation at 50° C, 15 minute incubation at 95° C, and 40 cycles each of 15 seconds at 94° C, 30 seconds at 55° C, and 30 seconds at 72° C. The fragment amplified included: 1) For LAMC2 (NM_005562) a 74-bp amplicon spanning exons 18 and 19 ; 2) For OASL (NM_003733), a 98-bp amplicon spanning exons 4 and 5; 3) for OSMR (NM_003999) a 113-bp amplicon spanning exons 13 and 14 ;4) For SERPINE1 (NM_000602), a 105-bp amplicon spanning exons 3 and 4; and as the reference gene, ACTB, a 146-bp amplicon spanning exons 3 and 4. Ten point standard curves were generated using Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) for all genes. The linear correlation coefficient (R2) was 0.99 or greater for all runs. The mean threshold cycles (Ct) values were calculated from the triplicate Ct values. Samples that had Ct values with standard deviation greater than 0.35 in their triplicate run were repeated. Mean Ct values were standardized to the mean Ct value of ACTB.

Results

Study population

The characteristics of the study participants are shown in supplementary material, Table S1. In general, the OSCC cases tended to be older and male, and they were more likely to be current smokers when compared to controls. The majority of the OSCC cases had advanced stage disease (approximately two thirds with AJCC stage III and IV).

Hierarchical Cluster and Principal Component Analysis

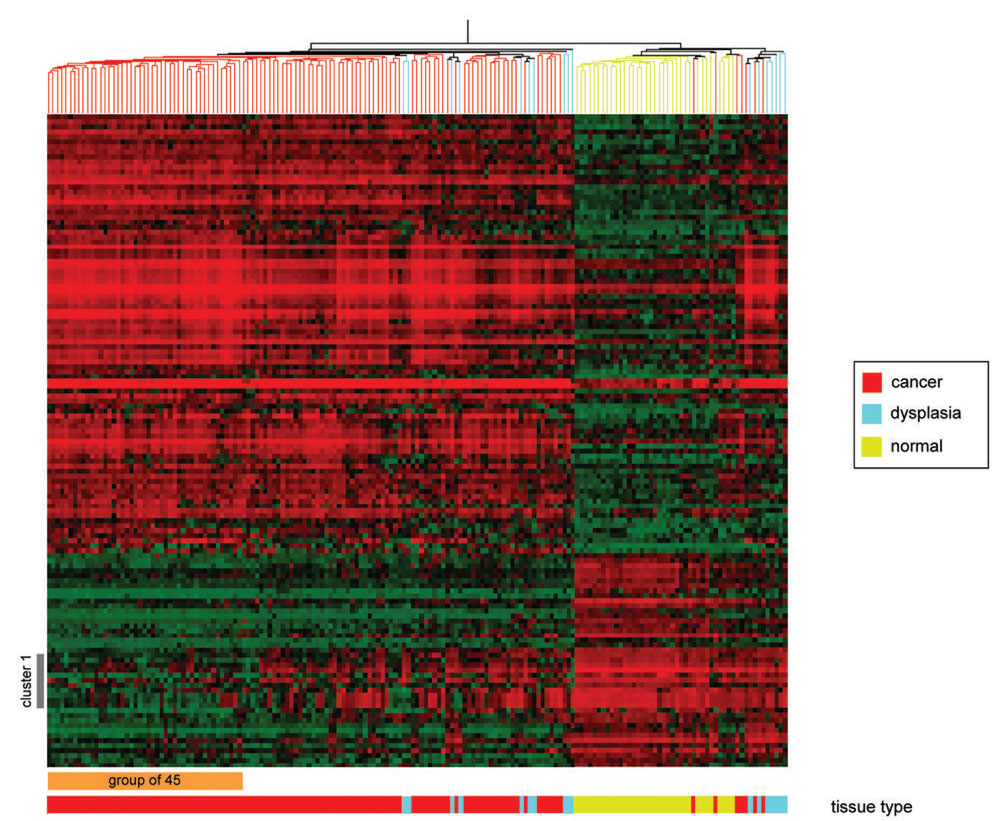

Results from a supervised hierarchical cluster analysis of the 119 OSCC cases, 35 normal controls and 17 dysplastic lesions using the 131 probe sets are shown in Figure 1. Although OSCC cases largely clustered separately from controls, 7 OSCC cases clustered with the controls. One cluster of genes (cluster 1, Figure 1) appears to show an increasing gradient of down-regulation progressing from normal to dysplastic to invasive lesions. Notably, neither the dysplasias nor those OSCC that misclassified with the normal controls demonstrated consistent down-regulation of these genes. In particular, this group of 12 probe sets (corresponding to nine genes) were completely down-regulated in a subset of 45 OSCC (cluster 1, Figure 1 and Table S2). We therefore hypothesized that the gene expression signature of this group of 45 OSCC represents one end of a continuum of gene expression that is characteristic of increasingly aggressive neoplastic behavior.

Figure 1.

Supervised hierarchical cluster analysis of the gene expression data. The 131 probe sets were clustered as described in the text. The dendogram at the top measures samples’ degree of relatedness in gene expression. The color bar underneath the heat map codes the samples according to tissue phenotype: normal in yellow, dysplasias in cyan and tumors in red. Each column in the heat map represents the expression levels for all genes in a particular sample, whereas each row represents the relative expression of a particular gene across all samples. The expression level of any gene in any given sample (relative to the mean expression level of that gene across all samples) is reported along a color scale in which red represents transcription up-regulation, green represents down-regulation, and the color intensity indicates the magnitude of deviation from the mean. Cluster 1 refers to a group of probe sets which appear to be only fully downregulated in a group of 45 patients labeled with an orange bar at the bottom of the heat map (see text).

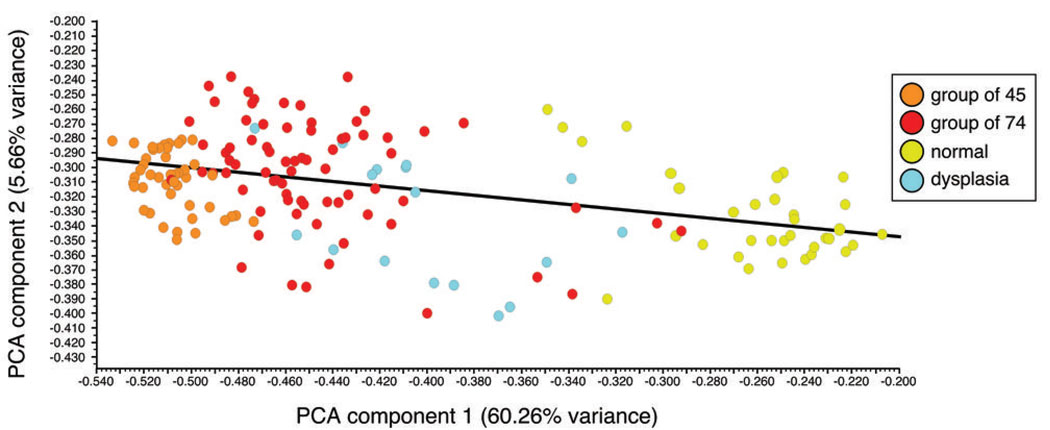

Figure 2 shows the results of a principal component analysis on the 131 probe set expression data based on the samples’ phenotype (normal, dysplasia or cancer). The first PC, which accounts for the greatest amount of variability, captured 60.26% of the variance, whereas the second PC captured 6.31%. On the basis of these two components alone, the controls and OSCC cases are at opposite ends of the spectrum with dysplasia samples in between (Fig. 2). In addition, the same group of 45 OSCC samples identified in the hierarchical cluster analysis is at one extreme on the basis of the first PC scores (Fig. 2). Although some dysplastic lesions have first PC scores that overlap with OSCC, none reached the first PC scores of the group of 45 OSCC samples.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis using the 131 probe sets. The first principal component (PC) is plotted on the x-axis and captures 63.28 % of the variance. The second PC is plotted on the y-axis and captures 5.66 % of the variance.

Differential Expression of the 45 sample sub-cluster

This cluster-defined OSCC subgroup was initially identified largely based on a qualitative analysis of the expression of a group of 12 down-regulated probe sets (Fig. 1, cluster 1). We utilized a linear regression model to more rigorously determine which probe sets were differentially expressed in this sub-cluster, compared to the rest of the OSCC cases. After adjusting for age and sex, we detected 62 out the 131 probe sets to be differentially expressed between these two groups (NFD = 1) (supplementary Table S2). Therefore, although the 12 down-regulated probe sets represent the most obvious change in expression in these 45 samples, nearly one-half of the 131 probe sets shows a distinctive signature in this sub-cluster.

Survival Analysis

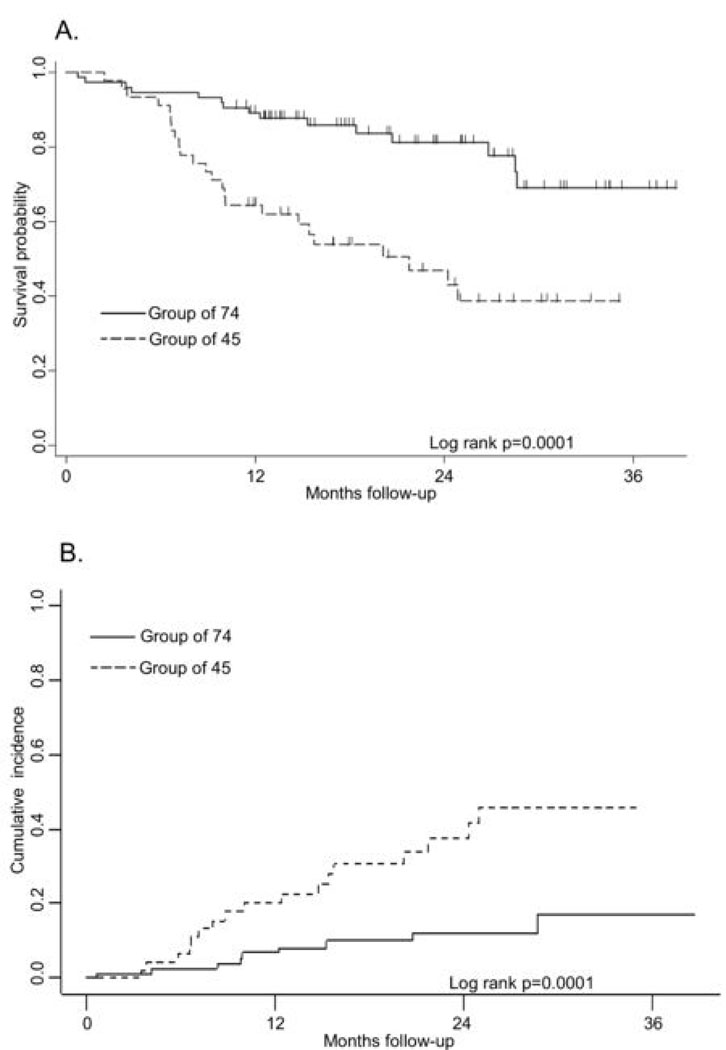

The patient characteristics for this sub-cluster compared to those of the rest of the cases are shown in Table 1. Patients in the 45-sample sub-cluster had more advanced disease, as determined by both tumor size and nodal metastasis, and were less likely to have tumors containing high-risk HPV types. The range of follow-up time for patients known to be alive at the end of the study was 10.7 to 38.7 months, with a median of 22.2 months. To test the hypothesis that this 45 sample sub-cluster had a more aggressive phenotype, we compared Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival (Figure 3A). The 3-year mean (% ± SE) overall survival for the 45 sample sub-cluster was 38.7 ± 0.09% compared to 69.1 ± 0.08 % (p=0.0001) for the other 74 samples. The estimated cumulative mortality (%± SE) due to OSCC at 3 years for the 45 sample sub-cluster was 45.7 ± 0.09% compared to 16.8 ± 0.06% (p=0.0003) for the other 74 samples (Figure 3B). We estimated hazard ratios (HR) for both overall and OSCC-specific mortality, adjusting for AJCC stage, age and sex. Patients from the 45 sample sub-cluster had a significantly higher rate of death, both due to overall (HR=3.31, 95% CI: 1.66, 6.58) and OSCC (HR= 5.43, 95% CI: 2.32, 12.73). These associations continued to be elevated following additional adjustment for HPV status (HR=3.43, 95% CI: 1.68, 6.99; HR=6.09, 95% CI: 2.48, 14.97, respectively). In addition, we adjusted for tumor site and treatment intensity separately and the results did not change appreciably (data not shown). Although a higher co-morbidity score was statistically significantly associated with both mortality outcomes, it neither confounded nor improved the precision of the association with OSCC sub-cluster when included in the Cox regression model (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of two cluster-defined OSCC subgroups

| Group of 45 | Group of 74 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=45) | (n=74) | |||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–39 | 4 | (8.9) | 1 | (1.4) |

| 40–49 | 8 | (17.8) | 10 | (13.5) |

| 50–59 | 12 | (26.7) | 28 | (37.8) |

| 60–88 | 21 | (46.7) | 35 | (47.3) |

|

Gender | ||||

| Male | 29 | (64.4) | 55 | (74.3) |

| Female | 16 | (35.6) | 19 | (25.7) |

|

AJCC Stage | ||||

| I | 7 | (15.6) | 21 | (28.4) |

| II | 3 | (6.7) | 11 | (14.9) |

| III | 7 | (15.6) | 9 | (12.2) |

| IV | 28 | (62.2) | 33 | (44.6) |

|

Tumor Size | ||||

| T1/T2 | 22 | (48.9) | 56 | (75.7) |

| T3/T4 | 23 | (51.1) | 18 | (24.3) |

|

Nodal Status | ||||

| N0 | 15 | (33.3) | 40 | (54.1) |

| N1 | 30 | (66.7) | 34 | (45.9) |

|

HPV status | ||||

| HPV negative | 35 | (77.8) | 43 | (58.1) |

| High-risk HPV positive | 9 | (20) | 30 | (40.5) |

| Low-risk HPV positive | 1 | (2.2) | 1 | (1.4) |

|

Vital Status | ||||

| Alive | 21 | (46.7) | 59 | (79.7) |

| Dead-OSCC | 17 | (37.8) | 9 | (12.2) |

| Dead-non OSCC | 3 | (6.7 | 6 | (8.1) |

| Dead -unknown cause | 4 | (8.9) | 0 | (0) |

Figure 3.

Survival and OSCC-specific mortality estimates in OSCC patients. The two groups were identified with hierarchical clustering analysis using the 131 differentially expressed genes in invasive OSCC as described in the text. A. Kaplan-Meier analysis of all-cause mortality. Vertical marks represent censored events. B. Cumulative incidence of OSCC-specific mortality.

Prediction models

We performed a stepwise Cox-proportional hazards regression based on these 131 probe sets to determine which, if any, were associated with OSCC-specific survival. Out of 150 patients, 109 were alive and 41 had died at the end of the follow-up period (Table S1). Among these, there were 27 OSCC-specific deaths, 10 non-OSCC-specific deaths and 4 deaths of unknown causes. We found that a model containing LAMC2 (laminin, gamma 2) alone performed best at identifying patients with the worst OSCC-specific survival. The subsequent nine models that were identified through our stepwise approach are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Top 10 multivariate Cox regression models of OSCC-specific survival

| Model | Gene Symbol (Affymetrix Probe set ID) | Model coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LAMC2 (207517_at) | 0.59151*LAMC2 |

| 2 |

OSMR (1554008_at) SERPINE1 (1568765_at) OASL (210797_at) |

0.42485*OSMR + 0.40482*SERPINE1 + 0.33483*OASL |

| 3 | SLC16A1 (209900_s_at) | 0.81478*SLC16A1 |

| 4 | KLF7 (1555420_at) | 0.60694*KLF7 |

| 5 |

THBS1 (201108_s_at) SLC16A1 (202235_at) |

0.44241*THBS1 + 0.43257*SLC16A1 |

| 6 | HOMER3 (204647_at) | 0.66632*HOMER3 |

| 7 | GRP68 (229055_at) | 0.63313*GRP68 |

| 8 | PDPN (204879_at) | 0.51904*PDPN |

| 9 | ANKRD35 (231118_at) | 0.58503*ANKRD35 |

| 10 |

CDH3 (203256_at) EPS8L1 (218779_x_at) |

0.75146* CDH3 − 0.50956* EPS8L1 |

The 3-D plot (supplementary information, Figure S1) shows that the risk scores from our top model (0.59151*LAMC2) are highly correlated with the risk scores from models containing terms for the first and second PCs from the analysis of the 131 probe sets. In addition, those patients with the highest risk scores from either the top model or the PC models are mostly the ones in the cluster-defined group of 45 patients.

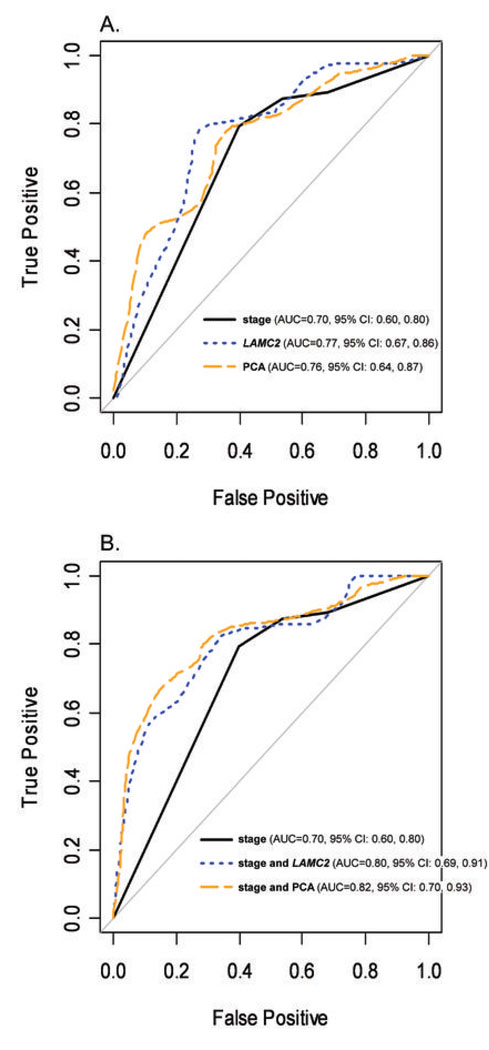

Comparing survival prediction models with AJCC stage

Results from the ROC analysis for each of the 5 models described above are shown in Figure 4. The AUCs for models with either gene expression alone or in combination with stage were higher than for a model with stage alone (Fig. 4A and B). The differences in the AUCs between models with ‘stage’ plus either ‘LAMC2’ or ‘PCA’ and stage alone were statistically significant (p= 0.013 and 0.008, respectively). The AUCs from the jackknife leave-one-out analyses (0.81 for the model with ‘stage’ and ‘LAMC2’ and 0.79 for the model with ‘stage’ and ‘PCA’) were virtually the same as those estimated using conventional methods.

Figure 4.

Receiver Operating Characteristic Analysis of 2-year Survival Comparing the Prognostic Ability of Stage with Gene Expression Data. A. ROC Curves for 2-year survival for, ‘stage’, ‘LAMC2’ and ‘PCA’. B. ROC Curves for 2-year survival for models ‘stage’, ‘stage and LAMC2’ and ‘stage and PCA’. C. Area Under the Curve (AUC) and bootstrapped 95% Confidence Intervals for all five models.

Validation of LAMC2, OSMR, SERPINE1, OASL, by qRT-PCR

The correlation coefficients for LAMC2, OSMR, SERPINE1 and OASL between microarray and qRT-PCR expression data for the 60 samples assayed were 0.65, 0.14, 0.74, and 0.89, respectively. Thus, with the exception of OSMR, our qRT-PCR results were well-correlated with those from microarray analyses.

Discussion

In this study, we focused on the expression of 131 probe sets that we previously found to be highly associated with OSCC (8), and show that OSCC can be further sub-classified on the basis of this gene expression signature. Moreover, this classification is independently associated with overall and OSCC-specific survival after adjustment for potential confounders such as age, sex, stage, tumor site, HPV status, and treatment intensity. Interestingly, none of the dysplastic lesions overlapped with the group of 45 OSCC cases on the basis of the first PC (Fig. 2) suggesting that this 45 sample sub-cluster represents a more invasive phenotype. This finding suggested to us that there might be a trend of differential expression of these 131 probe sets in OSCC, such that the varying degrees of up- or down-regulation of some genes might be of prognostic significance. The observation that the score (‘PCA’) that summarized the expression levels of all 131 probe sets as a combination of the first and second PCs was significantly associated with overall survival supports this hypothesis.

There are various risk factors that may be of potential significance in our cohort. First, HPV infection is now emerging as a potentially important predictor of prognosis in patients with oropharyngeal sqaumous cell carcinoma (18). However, we did not find HPV to either be independently associated with survival (data not shown) or confound the association between gene expression and survival. This is likely due to the fact that the majority of our patients (73%) had oral cavity (as opposed to oropharyngeal) tumors where HPV status has not been shown to play a significant role. Another potential risk factor in our cases that deserves further clarification is treatment. It is possible that treatment modality could modify the association between gene expression data and survival, but our study lacked sufficient numbers to test this hypothesis. However, evidence from randomized clinical trials strongly indicates that the different treatment modalities for advanced head and neck cancer do not show significant differences in survival (19)(20)(21). Thus, we think it is unlikely that, had we sufficient numbers of subjects with each treatment type to conduct stratum-specific analyses, meaningful differences would have been observed.

Another important finding of this study is that similar results were obtained between summary measures of all 131 probe sets and our top model containing only one gene. The risk scores from models with each of the first two principal components and our top gene-specific model (0.59151*LAMC2) are highly correlated (Fig. S1). This underscores the possibility for reducing the dimensionality of the data not only to the summary of principal components, but to one single probe set without substantial loss of information. This is important because it will be easier to implement molecular tests for clinical use if fewer molecules need to be measured.

Two previous studies by Chung et al have shown an association between microarray-derived expression data and clinical outcomes in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) (4)(5). In the first study, a 582 gene set from 60 HNSCC classified the tumors into 4 different subclasses with statistically significant differences in recurrence-free survival. In a separate study using formalin-fixed tissues, the authors identified a second 950 gene signature from unsupervised analysis and a 75-gene list from supervised PCA that was predictive of recurrence. Using the Unigene ID numbers for each gene, we determined that these two previous signatures have 39 genes in common. In contrast, comparison of our 131 probe sets with the gene lists from the previous two studies revealed only one gene shared in all three lists: solute carrier family 16, member 1 (SLC16A1). This gene comprises our third top model for OSCC-specific survival (Table 2). Subsequently, Pramana et al tested 42 genes with known function out of the 75-gene list from Chung et al , and showed that these genes were predictive of locoregional control in their own data set (6)(5). Only two genes overlapped between our 131 probe set list and these 42 genes: Glycine-rich protein (GRP3S) (MACF1) and collagen type V, alpha 1 (COL5A1).

There are likely to be many reasons for the lack of more substantial overlap between these gene lists. For example, the 950 and 75 gene lists were derived from formalin-fixed samples and a different array platform (5). In addition, the samples in the studies of Chung et al were from multiple head and neck sites whereas our samples were limited to the oral cavity and oropharynx. The end points also differed between studies, since we analyzed overall and OSCC-specific survival, and Chung et al examined recurrence-free survival (5)(8). The statistical approaches to derive these gene signatures were also substantially different (12)(5)(8). Given all these issues, overlapping genes in particular should be further investigated for their potential generalizability in predicting clinical outcomes.

Among the 131 genes used in the supervised cluster analysis, 62 probe sets were differentially expressed between the group of 45 patients and the remaining OSCC. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of the 62 probe sets showed an overrepresentation of genes involved in cell migration; cell-to-cell signaling and interaction; and cellular growth and proliferation. In addition, five of the genes in our top 10 models predictive of OSCC-specific mortality, such as LAMC2, SERPINE1, THBS1, PDPN and CDH3 play a role in cell motility and cell-to-cell signaling, implying that expression of genes involved in the process of invasion and metastasis is an important determinant of outcome in patients with these malignancies (22)(23)(24)(25)(26)(27)(28). Specifically, the proteins encoded by these genes reside in the extracellular matrix and function in cell adhesion and migration. For example, LAMC2, the gene comprising our top model encodes the γ2 subunit of laminin-5 (Ln-5) which upon cleavage by MMP-2, appears to release a domain with EGD-like repeats that has been shown to bind to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), activate EGFR signaling, and promote cell motility (22). In addition, this LN-5 γ2 subunit has been found overexpressed at the invasive front of several tumors and, in some, this has been associated with poor prognosis (29)(30)(31). Two other genes in our top models, THBS1 and PDPN, have both been ascribed a role in platelet aggregation and may be involved in tumor metastasis by facilitating tumor cell-platelet interactions and platelet-facilitated tumor cell metastasis (25). It is also known that THBS1 binds with members of the tenacin family and SPARC/osteonectin (25). In fact, tenacin C and SPARC were found to be significantly upregulated at both the gene expression and protein levels in this and other studies by our group (2)(32). In addition, P-cadherin (CDH3), a component of our 10th model, is associated with cell-to-cell signaling and we have previously found this gene to be significantly downregulated in metastatic tumors cell isolated from lymph nodes (33). The findings in this study showing that the dysregulation of these genes’ expression is associated with OSCC-specific survival are consistent with the growing body of literature that suggest that tumor proliferation and metastasis may be in great part mediated by the complex interactions between extracellular matrix proteins and cell-surface receptors.

The functions of other genes in our top 10 models are less understood. OASL appears to be a member of a family of Trips (Thyroid hormone-interacting proteins) and may thus be involved in signal transduction in the presence of thyroid hormone (34). Oncostatin M receptor (OSMR) is a member of the IL6 cytokine family and is thought to be involved in signal transduction and proliferation (35)(36). However, we could not validate the expression of this gene with qRT-PCR. It is possible that this finding is a false positive and/or the oligonucleotides on the Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 arrays are not specific for this gene.

This is the first study we are aware of demonstrating an association between a gene signature and OSCC-specific survival, and in particular how the use of gene expression data can improve upon AJCC stage in predicting survival. We showed that regression models that combined stage with gene expression had significantly higher AUCs than stage alone (Figure 4). We acknowledge the potential for over-optimism in the estimated AUCs for the models containing gene expression covariates since we used the same sample set to select the top models, estimate risk scores, and assess the association of risk scores with survival. Although the results were essentially unchanged when we used a jackknife leave-one-out analysis, it is important to recognize that this only addresses one portion of the potential over-estimation of the AUC estimates since the underlying data remain the same. Further studies with large independent data sets will be needed to validate our models, but such gene expression data sets for oral cancer of sufficient size and follow-up time are not yet publicly available. As we enroll more subjects and accumulate longer follow-up time, we will also be able to address whether these results are stage-specific. This will in turn allow us to determine which patients would benefit most from these AUCs improvements and how to best implement gene expression into clinical practice. Nevertheless, this is the first study in head and neck cancer that begins to address how gene expression data can compliment AJCC stage in predicting survival. Given the recent emphasis on genome-wide gene expression studies to find signatures predictive of clinical outcomes, and the abundance of potential predictors emerging, studies such as this will be needed to determine how to integrate genetic data into clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH grants R01CA095419 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (E. Méndez, J.R. Houck, D.R. Doody, W. Fan, P. Lohavanichbutr, B. Yueh, N.D. Futran, M.P. Upton, D.G. Farwell, L. Zhao, S. Schwartz and C. Chen) and 1KL2RR025015-01 from the National Center for Research Resources (E. Méndez, T.C. Rue and P.J. Heagerty); and institutional funds from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (C. Chen).

Footnotes

Statement of Translational Relevance:

We set out to determine if OSCC could be further sub-classified on the basis of 131 probe sets (108 known genes) which we previously found to be differentially expressed between OSCC and normal controls, and whether this sub-classification was associated with survival. In this study, we found that: 1) there were significant survival differences in cluster analysis-defined OSCC subgroups; 2) this classification is independently associated with overall and OSCC-specific survival after adjustment for potential confounders such as age, sex, stage, tumor site, HPV status and treatment intensity; and 3) genetic expression data and AJCC stage combined predict survival of OSCC patients better than AJCC stage alone.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of this kind for oral cancer, and the only one that describes an association between gene expression profiling and OSCC-specific survival. This study is prospective and predictive of clinical outcomes and it surpasses other published studies in its effort to address how gene expression data can complement AJCC stage in predicting survival – a key and novel contribution to the field of oral and head and neck cancer.

References

- 1.Carvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano JA, Kowalski LP. Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: A site-specific analysis of the SEER database. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:806–816. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Méndez E, Cheng C, Farwell DG, et al. Transcriptional expression profiles of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer. 2002;95:1482–1494. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Hermans J, Molenaar J, Briaire JJ, le Cessie S. Prediction of survival in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2001;23:718–724. doi: 10.1002/hed.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung CH, Parker JS, Karaca G, et al. Molecular classification of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas using patterns of gene expression. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung CH, Parker JS, Ely K, et al. Gene Expression Profiles Identify Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Activation of Nuclear Factor-{kappa}B Signaling as Characteristics of a High-risk Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8210–8218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pramana J, van den Brekel MW, Van Velthuysen ML, et al. Gene expression profiling to predict outcome after chemoradiation in head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1544–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginos MA, Page GP, Michalowicz BS, et al. Identification of a gene expression signature associated with recurrent disease in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 2004;64:55–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Méndez E, Houck J, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies genes predictive of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2152–2162. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:593–602. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccirillo JF, Creech C, Zequeira R, Anderson S, Johnston AS. Inclusion of Comorbidity into Oncology Data Registries. Journal of Registry Management. 1999;26:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohavanichbutr P, Houck J, Fan W, et al. Genome-wide gene expression profiles of HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer: potential implications for treatment choices. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1001/archoto.2008.540. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas JG, Olson JM, Tapscott SJ, Zhao LP. An efficient and robust statistical modeling approach to discover differentially expressed genes using genomic expression profiles. Genome Res. 2001;11:1227–1236. doi: 10.1101/gr.165101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu XL, Olson JM, Zhao LP. A regression-based method to identify differentially expressed genes in microarray time course studies and its application in an inducible Huntington's disease transgenic model. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1977–1985. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.17.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1980. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M, et al. A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1229–1235. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000;56:337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasson JH, Sox HC, Neff RK, Goldman L. Clinical prediction rules. Applications and methodological standards. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:793–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509263131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefebvre JL, Chevalier D, Luboinski B, et al. Larynx preservation in pyriform sinus cancer: preliminary results of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Cooperative Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:890–899. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.13.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schenk S, Hintermann E, Bilban M, et al. Binding to EGF receptor of a laminin-5 EGF-like fragment liberated during MMP-dependent mammary gland involution. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:197–209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bajou K, Masson V, Gerard RD, et al. The plasminogen activator inhibitor PAI-1 controls in vivo tumor vascularization by interaction with proteases, not vitronectin. Implications for antiangiogenic strategies. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:777–784. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen H, Brunner N, Francis D, et al. Prognostic impact of urokinase, urokinase receptor, and type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor in squamous and large cell lung cancer tissue. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4671–4675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bornstein P. Diversity of function is inherent in matricellular proteins: an appraisal of thrombospondin 1. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:503–506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yee KO, Streit M, Hawighorst T, Detmar M, Lawler J. Expression of the type-1 repeats of thrombospondin-1 inhibits tumor growth through activation of transforming growth factor-beta. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63319-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato Y, Sasagawa I, Kaneko M, et al. Aggrus: a diagnostic marker that distinguishes seminoma from embryonal carcinoma in testicular germ cell tumors. Oncogene. 2004;23:8552–8556. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler MA, Zhang JN, Westerhausen DR, Jr, Billadello JJ. A novel protein interacts with the major transforming growth factor-beta responsive element in the plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21500–21504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pyke C, Romer J, Kallunki P, et al. The gamma 2 chain of kalinin/laminin 5 is preferentially expressed in invading malignant cells in human cancers. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:782–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niki T, Kohno T, Iba S, et al. Frequent co-localization of Cox-2 and laminin-5 gamma2 chain at the invasive front of early-stage lung adenocarcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto H, Itoh F, Iku S, Hosokawa M, Imai K. Expression of the gamma(2) chain of laminin-5 at the invasive front is associated with recurrence and poor prognosis in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:896–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi P, Jordan CD, Méndez E, et al. Examination of oral cancer biomarkers by tissue microarray analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:539–546. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Méndez E, Fan W, Choi P, et al. Tumor-specific genetic expression profiles of metastatic oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2007;29:803–814. doi: 10.1002/hed.20598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JW, Choi HS, Gyuris J, Brent R, Moore DD. Two classes of proteins dependent on either the presence or absence of thyroid hormone for interaction with the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:243–254. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.2.7776974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosley B, De Imus C, Friend D, et al. Dual oncostatin M (OSM) receptors. Cloning and characterization of an alternative signaling subunit conferring OSM-specific receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32635–32643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gearing DP, Comeau MR, Friend DJ, et al. The IL-6 signal transducer, gp130: an oncostatin M receptor and affinity converter for the LIF receptor. Science. 1992;255:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1542794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.