Abstract

Background

This study examined relations among cumulative risk, nurturant and involved parenting, and behavior problems across early childhood.

Methods

Cumulative risk, parenting, and behavior problems were measured in a sample of low-income toddlers participating in a family-centered program to prevent conduct problems.

Results

Path analysis was utilized to examine longitudinal relations among these constructs, with results supporting an indirect effect of cumulative risk on externalizing and internalizing problems through nurturant and involved parenting.

Conclusion

Results highlight the importance of cumulative risk during early childhood, and particularly the effect that the level of contextual risk can have on the parenting context during this developmental period.

Keywords: Cumulative risk, parenting, externalizing problems, internalizing problems, behavior problems, risk factors, family functioning, longitudinal studies, prevention

The cumulative risk literature indicates that as the number of contextual risk factors accumulate, child externalizing and internalizing problems increase (e.g., Ackerman, Izard, Schoff, Youngstrom, & Kogos, 1999; Jones, Forehand, Brody, & Armistad, 2002). Identifying predictors of behavior problems during early childhood is a worthwhile goal for cumulative risk research due to increased levels of later psychiatric diagnosis and related problems among children with early-starting externalizing and internalizing problems (Feng, Shaw, & Silk, 2008; Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002). Previous research linking cumulative risk levels to later behavior problems have included more distal contextual risks (e.g., maternal education) and more proximal risks (e.g., parent–child relationship quality); however, when proximal risks are used in conjunction with more distal risks, it becomes difficult to unpack the underlying mechanisms through which risk affects the child. From an ecological perspective (e.g., Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), examining proximal processes as mediators of relations between distal indices of risk and child outcomes provides a more theoretically compelling approach to inform risk research, preventive interventions, and social policy. This approach may be particularly useful in early childhood when parent–child relationships are paramount and effects of contextual risk on child behavior may be largely accounted for by the quality of the caregiving context. The present study was designed to examine the relations among cumulative risk, parenting, and child behavior problems using a sample of ethnically diverse, low-income families with toddlers at risk for early-starting problem behavior and followed longitudinally to the preschool period.

Cumulative risk research

A cumulative risk index is typically tabulated by summing the number of dichotomized risk factors (Sameroff, Seifer, & McDonough, 2004). Research on cumulative risk and child outcomes began with Rutter's (1979) investigation of the Isle of Wight sample. Rutter created a cumulative risk index across six factors: marital discord, low socioeconomic standing, household overcrowding, paternal criminality, maternal psychiatric disorder, and child involvement with foster care. No differences were found in child adjustment for families with zero versus one risk factor, but a greater than fourfold increase occurred with the accumulation of two risks and an additional multiplicative increase at the level of four or more risks. Following Rutter's early work, numerous investigations demonstrated associations between cumulative risk and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems (e.g., Blanz, Schmidt, & Esser, 1991; Jones et al., 2002). In general, these latter investigations supported a linear relation between the number of risk factors and child outcomes, including cumulative risk research in early childhood (Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen, & Sroufe, 2005; Sanson, Oberklaid, Pedlow, & Prior, 1991).

Many cumulative risk indexes focused primarily on the wider contextual ecology and included indicators such as residential instability and police contact (e.g., Ackerman, Brown, & Izard, 2004). Other research took a comprehensive approach to generating indices of cumulative risk and included factors more proximal to the child's behavioral development (e.g., parental warmth) along with more distal ecological factors (Gassman-Pines & Yoshikawa, 2006). Yet another approach partitioned risk into separate individual sub-indexes by sociodemographic, parenting, child, and peer domains (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1998). Although each approach increases understanding of cumulative risk and child development, the approaches serve somewhat different purposes. When risk indexes include both distal ecological risk and more proximal factors in children's adjustment (e.g., parenting), the opportunity to examine proximal factors as mediators or moderators of relations between broader contextual risk and child outcomes is lost. For example, Ackerman and colleagues (1999) demonstrated that maternal positive emotionality attenuated the relation between cumulative risk and child outcomes. Because the majority of previous research has included proximal variables in the risk index, examination of mediators and moderators of the relation between cumulative risk and child outcomes has been limited.

Cumulative risk and parenting

Our primary goal was to examine a particularly relevant proximal variable, nurturant and involved parenting, as a mediator of relations between cumulative contextual risk and externalizing and internalizing problems in high-risk young children. The focus on cumulative contextual risk is consistent with the central tenets of Bronfenbrenner's (1979) ecological perspective on human development. A specific outgrowth of the ecological perspective is the need for process-oriented research on relations among the ecological context, proximal processes, and child dysfunction in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Parenting represents an important proximal process during early childhood. First, the parent–child relationship is the primary relationship context in early development (Sroufe, 1983). Secondly, the importance of the socialization of appropriate behavior as children transition from toddlerhood into the preschool years and beyond makes the provision of nurturant and involved parenting vital during this developmental period (Greenberg, Speltz, & DeKlyen, 1993). However, nurturant and involved parenting may be particularly challenging during early childhood due to toddlers’ increased physical mobility and noncompliance (Shaw, Bell, & Gilliom, 2000). Children who experience suboptimal parenting are at greater risk for early externalizing problems initiated by coercive cycles of noncompliance and harsh parental reprisals (Patterson, 1982) or early internalizing problems initiated by parental unresponsiveness to inhibition or fear. Furthermore, children who demonstrate early-starting externalizing or internalizing problems are more likely to persist with elevated levels of these problems, often leading to psychiatric diagnosis (Feng et al., 2008; Moffitt et al., 2002).

When examining individual contextual risk factors, research on the development of children's behavior problems is consistent with proximal processes in a broader ecological framework. For example, parental discipline and monitoring mediated relations between socioeconomic status and delinquency among school-age children (Larzelere & Patterson, 1990). However, in many circumstances parents may be able to cope with a single risk factor such as low income level. As ecological risk factors mount, as with an impoverished single parent raising four children in a dangerous neighborhood, the likelihood of measurable harm to the parenting context is likely to increase substantially. When multiple risk factors are present, the capacity for adequate attention and warmth directed toward children in the home is likely to diminish, increasing the risk for persistent externalizing and internalizing problems.

The theoretical propositions described above remain somewhat speculative because little research has examined whether a risk index predicts parenting and whether parenting mediates associations between cumulative risk and early childhood problem behavior. In a primarily middle-class, normative sample, a cumulative risk index encompassing factors such as ethnic minority status, poverty, single parenthood, and maternal depression predicted parenting quality (Lengua, Honorado, & Bush, 2007). Furthermore, parenting at age 3 mediated relations between cumulative risk and child social competence and effortful control six months later. These findings warrant application to higher-risk samples and suggest that parenting quality may also mediate relations between cumulative risk and externalizing and internalizing problems in young children.

Goals of the current study

This investigation of cumulative risk, parenting, and child externalizing and internalizing problems occurred in the context of an evaluation of a prevention program for toddlers living in poverty and at risk for clinically elevated levels of conduct problems. In developing a cumulative risk index, we selected constructs reflecting the range of distal indicators in previous risk research (e.g., Ackerman et al., 2004; Krishnakumar & Black, 2002; Lengua et al., 2007; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network., 2004; Rutter, 1979): neighborhood dangerousness, single adult in the home, household overcrowding, adolescent parenthood, legal conviction among adults in the home, primary caregiver with drug or alcohol problems, and primary caregiver with less than a high school education. The seven risk factors were also selected because they were likely to tax caregivers’ psychological resources and impair the provision of nurturant and involved parental care. We hypothesized direct relations between the risk index at age 2 and observed parental nurturance and involvement at age 3 such that higher scores on the risk index were expected to predict less nurturant and involved parenting. We expected parental nurturance and involvement at age 3 to directly predict externalizing and internalizing problems at age 4 and to account for an indirect effect of cumulative risk on preschoolers’ behavior problems. The research design allowed us to statistically control for the stability of behavior problems from age 2 to 4 and to account for the established intervention effect of involvement in the prevention program on behavior problems (Dishion et al., in press).

Method

Participants

Mother–child dyads were recruited between 2002 and 2003 from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in metropolitan Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Eugene, Oregon, and within and outside the town of Charlottesville, Virginia. Families were invited to participate if they had a son or daughter between age 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months. Screening procedures were developed to recruit families of children at especially high risk for conduct problems. Recruitment risk criteria were defined as one standard deviation above normative averages on screening measures in at least two of the following three domains: (1) child behavior problems (conduct problems – Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory; Robinson, Eyberg, & Ross, 1980; or high-conflict relationships with adults – Adult Child Relationship Scale; adapted from Pianta, 1995), (2) primary caregiver problems (maternal depression – Center for Epidemiological Studies on Depression Scale; Radloff, 1977; or daily parenting challenges – Parenting Daily Hassles; Crnic & Greenberg, 1990; or self-report of substance or mental health diagnosis, or adolescent parent at birth of first child), and (3) socio-demographic risk (low education achievement – less than or equal to a mean of 2 years of post-high-school education between parents and low family income using WIC criterion). The research protocol was approved by the respective universities’ Institutional Review Boards, and participating primary caregivers provided informed consent.

Recruitment

Of the 1666 families who had children in the appropriate age range and who were contacted at WIC sites across the three study sites, 879 met the eligibility requirements (52% in Pittsburgh, 57% in Eugene, 49% in Charlottesville) and 731 (83.2%) agreed to participate (88% in Pittsburgh, 84% in Eugene, 76% in Charlottesville). The children in the sample had a mean age of 29.9 months (SD = 3.2) at the time of the age 2 assessment. Of the 731 families (49% female), 272 (37%) were recruited in Pittsburgh, 271 (37%) in Eugene, and 188 (26%) in Charlottesville. Across sites, primary caregivers self-identified as belonging to the following ethnic groups: 28% African American, 50% European American, 13% biracial, and 9% other groups (e.g., American Indian, Native Hawaiian). Thirteen percent reported being Hispanic American.

Sites did not differ on basic demographics, including percentage with low family income (below $20,000 per year), target child age, or target child gender; however, sites differed in ethnicity distribution. For example, approximately one half of the sample in Pittsburgh was African American. There were a similar percentage of ethnic minorities in Eugene, but the minority groups in Eugene were primarily Hispanic or biracial. In Charlottesville, ethnicity was relatively evenly distributed across African American, European American, and other ethnic groups. Because ethnic minority status was a salient demographic difference across sites, we examined ethnic minority vs. non-minority group differences in the path analytic models presented below.

Retention

Of the 731 families who initially participated, 659 (90%) were available at the one-year follow-up and 619 (85%) participated at the two-year follow-up when children were between 4 and 4 years 11 months old. For the present study, 557 families had complete data and were included in the analyses. The analyses focused on the 557 families with complete data because tests of indirect effects with bias-corrected bootstrap sampling methods in AMOS 5.0 (see Results for more detail on these procedures) are not possible with missing data. Selective attrition analyses revealed no significant differences between members of the initial sample with missing data and the 557 families with complete data on the risk index, parenting measure, or on behavior problem ratings.

Design and procedure

Assessments were scheduled yearly at ages 2, 3, and 4. Participating primary caregivers (PC) were scheduled for a 2.5-hour home visit, and alternative caregivers (AC; e.g., fathers, grandmothers) were also invited to participate when applicable. Over 96% of PCs at the initial assessment were biological mothers; in all other cases, non-maternal custodial caregivers (e.g., biological fathers) served as the PC. After 15 minutes of child free play, each PC and child participated in a clean-up task (5 minutes), followed by a delay of gratification task (5 minutes), 4 teaching tasks (3 minutes each with the last one completed with the AC), a second free play (4 minutes), a clean-up task with the AC (4 minutes), two inhibition-inducing situations (2 minutes each), and a meal preparation and lunch task (20 minutes). Because AC involvement varied across families and across time, the present study focused on PC reports on risk indicators and child outcomes. To ensure blindness, the examiner opened a sealed envelope, revealing the family's group assignment after the assessment was completed. Examiners carrying out follow-up assessments were not informed of the family's assigned condition.

Families randomly assigned to the intervention condition were scheduled to meet with a parent consultant for two or more sessions of a family check-up (FCU) intervention. The FCU is a brief, three-session intervention based on motivational interviewing. This procedure for families in the intervention condition was repeated at ages 3 and 4. A more detailed description of the intervention is available in a publication covering a separate, single-site evaluation of the FCU (Shaw, Dishion, Supplee, Gardner, & Arnds, 2006). For the present study, the cumulative risk index was based on measures collected at the age 2 assessment, observations of parenting were based on the age 3 assessment, and behavior problem scores came from PC ratings at ages 2 and 4.

Measures

Cumulative risk index

The cumulative risk index was generated from seven indicators of socio-demographic risk. These seven indicators were: (1) teen parent status, (2) PC education level, (3) single adult in the home, (4) household overcrowding, (5) household member legal conviction, (6) PC drug or alcohol problem, and (7) neighborhood dangerousness. Families received a score of ‘1’ for each indicator if present or a score of ‘0’ if absent. Descriptions of criteria, data sources, and the percentage of families meeting each criteria are presented in Table 1. In accordance with similar cumulative risk research (e.g., NICHD Early Child Care Research Network., 2004), criteria were established so that that approximately 25% of the sample would meet criteria for each risk indicator. For five of the risk indicators, the 25% guideline was attained within three percentage points. For neighborhood dangerousness and drug or alcohol problems the most appropriate cut-points led to a lower percentage meeting criteria for the indicator. Although income poverty is often included in cumulative risk indices, we did not include income as an indicator of risk in the present study because approximately 75% of families had an income that fell in the same range as the US poverty line and over 93% of incomes were less than 200% of the poverty line.

Table 1.

Cumulative risk indicators, descriptions, and percentage meeting criteria

| Indicator | Description of criteria and source | % |

|---|---|---|

| Teen parent | Under 18 years of age at first child's birtha | 22.7 |

| Low education | Primary caregiver did not complete high school or obtain a GEDb | 23.5 |

| Single parent | Single adult in the homeb | 25.4 |

| Overcrowding | a) 4 or more children or b) fewer rooms than people (excluding bathrooms and hallways)b | 28.6 |

| Criminal conviction | At least one household resident with a criminal conviction since the child's birthb | 26.1 |

| Drug/Alcohol problem | The primary caregiver met one or more of the following criteria: a) sometimes, often, or very often argumentative or irritable when drinking, b) drinks everyday and drinks 3−4 or more drinks most of the time, c) uses marijuana or hard drugs more than once a month, or d) uses more than one hard drug about once per monthc | 12.8 |

| Neighborhood dangerousness | One standard deviation or more above the sample mean of 2.93 (SD = 2.61) on 15-item Dangerousness scale (sample item: ‘There was a gang fight near my home’). Primary caregivers selected ‘never,’ ‘once,’ ‘a few times,’ or ‘often’ for each item.d | 16.8 |

Note.

Initial Screening Questionnaire.

Age 2 Demographic Questionnaire.

Drug and Alcohol Questionnaire (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003).

Me and My Neighborhood Questionnaire (based on the City Stress Inventory; Ewart & Suchday, 2002).

Early childhood problem behavior

PC reports on the Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1.5−5 (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) were used to assess internalizing and externalizing problems. The CBCL Externalizing factor includes items assessing aggression and rule-breaking behavior, and the Internalizing factor includes items assessing anxiety, depressive symptoms, withdrawal, and somatic complaints. The Externalizing factor demonstrated excellent internal reliability in this sample (α = .86 and .86 at ages 2 and 4, respectively), as did the Internalizing factor (α = .82 and .91 at ages 2 and 4, respectively).

Parental nurturance and involvement

An adaptation of the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME; Caldwell & Bradley, 2003) was used to index parental nurturance and involvement. The original HOME measure includes 36 items that assess the quality and quantity of support and stimulation in the home environment. The HOME was selected because it is designed for use following naturalistic observation of the parenting context. Thus, the HOME was an ideal measure to use following 2.5-hour home visits with numerous opportunities to observe parent–child interaction and parental provision of warmth and support. The lead examiner from the family home assessment completed the HOME at the end of the visit. Examiners were trained on the use of the HOME and used a detailed coding manual to complete the HOME (Caldwell & Bradley, 2003). Item content was streamlined for the present study to eliminate items that typically require caregiver interviews and was based entirely on examiner observation. This version consisted of 21 items from the Responsivity, Acceptance, and Involvement scales and demonstrated excellent internal reliability (α = .75). Sample items include ‘parent spontaneously praises child at least twice,’ ‘parent keeps child in visual range, looks often,’ and ‘parent does not scold or criticize child during visit.’

Results

Table 2 presents means, standard deviations, and ranges for the risk index, parenting, and behavior problems among the 557 families with complete data. As the CBCL T-scores indicate, the initial (age 2) mean for Externalizing was nearly one standard deviation above the normative mean, supporting the high-risk nature of the sample at the study's outset. CBCL raw scores were used for all subsequent analyses because T-scores represent a rank order relative to a standardized group whereas raw scores represent the child's actual change in behavior (Stoolmiller & Bank, 1995). Preliminary correlation analyses between individual risk factors and CBCL raw scores at age 4 indicated very small and largely non-significant correlations, ranging from correlations of −.04 to .11 for Externalizing (with the highest correlation for the low education risk factor, r= .11, p < .01) and correlations of −.08 to .14 for Internalizing (with the highest correlation for the low education risk factor, r = .14, p < .01).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and range of scores for study variables

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 2: | ||||

| Cumulative risk index | 0 | 4 | 1.54 | 1.12 |

| CBCL Externalizing (Raw) | 1 | 43 | 20.71 | 7.26 |

| CBCL Externalizing (T) | 32 | 88 | 59.47 | 8.13 |

| CBCL Internalizing (Raw) | 1 | 38 | 12.36 | 6.30 |

| CBCL Internalizing (T) | 33 | 78 | 56.29 | 8.16 |

| Age 3: | ||||

| HOME parenting | 2 | 21 | 16.08 | 3.33 |

| Age 4: | ||||

| CBCL Externalizing (Raw) | 0 | 44 | 15.93 | 8.58 |

| CBCL Externalizing (T) | 28 | 89 | 53.75 | 10.41 |

| CBCL Internalizing (Raw) | 0 | 44 | 10.69 | 7.11 |

| CBCL Internalizing (T) | 29 | 82 | 53.28 | 9.94 |

Because only 1% of the families met criteria for more than 4 of the risk indicators, risk levels of ‘5’ or ‘6’ were transformed to ‘4’ for the risk index. Table 3 presents the frequency of the families with each level of cumulative risk and lists the HOME parenting scores at age 3 and CBCL Internalizing and Externalizing raw scores at age 4 for each level of cumulative risk. In accord with the majority of recent research, the cumulative risk index was treated as a continuous variable for all subsequent analyses. All correlations between the risk index, child behavior problems, and parenting were significant (p < .05; see Table 4).

Table 3.

Frequencies, age 3 HOME parenting score, and age 4 CBCL scores for each level of cumulative risk

| Risk index score | N | Percent of total | HOME parenting | CBCL Externalizing | CBCL Internalizing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 108 | 19.4 | 16.90 | 15.60 | 10.10 |

| 1 | 181 | 32.5 | 16.61 | 15.07 | 10.39 |

| 2 | 157 | 28.2 | 15.89 | 15.52 | 10.43 |

| 3 | 82 | 14.7 | 15.05 | 17.59 | 11.48 |

| 4+ | 29 | 5.2 | 13.72 | 20.10 | 13.97 |

Table 4.

Bivariate correlations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intervention status | ||||||

| 2. Cumulative risk | −.01 | |||||

| 3. Age 2 Externalizing | .02 | .15** | ||||

| 4. Age 2 Internalizing | .03 | .17** | .49** | |||

| 5. Nurturant/Involved parenting | −.01 | −.24** | −.12** | −.21** | ||

| 6. Age 4 Externalizing | −.08* | .11** | .49** | .30** | −.22** | |

| 7. Age 4 Internalizing | −.07 | .10* | .25** | .55** | −.23** | .63** |

p < .05

p < .01.

Model estimation

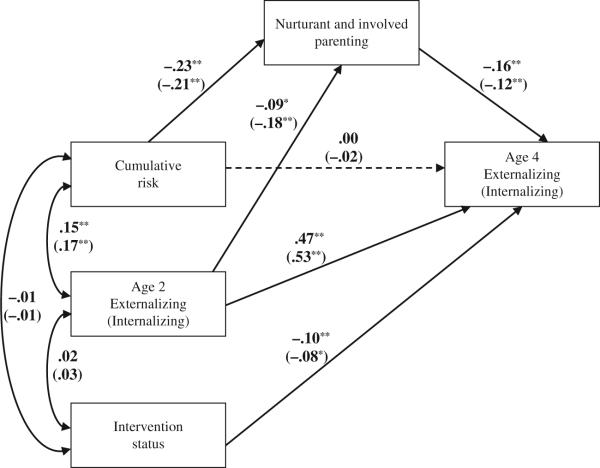

Path analytic models were examined with maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS 5.0 (Arbuckle, 2003). Figure 1 presents the path analytic model to examine predictors of externalizing problems at age 4, with standardized coefficients for the separate model to examine internalizing problems at age 4 in parentheses. This model included three exogenous predictors: (1) cumulative risk, (2) intervention status, and (3) age 2 externalizing problems; and two endogenous variables: (1) nurturant and involved parenting and (2) age 4 externalizing problems. In keeping with our theoretical framework, direct paths were included from the risk index to nurturant and involved parenting and from nurturant and involved parenting to age 4 externalizing problems. To control for stability in externalizing problems, a direct path was included from age 2 to age 4 externalizing problems. Direct paths from age 2 externalizing problems to nurturant and involved parenting and from intervention status to age 4 externalizing problems were also included to statistically control for child effects on parenting and the documented intervention effects on child externalizing problems. Lastly, a direct path from cumulative risk to age 4 externalizing problems was included to evaluate whether an indirect effects model was most appropriate or whether direct relations also existed between these two constructs.

Figure 1.

Models of relations among cumulative risk, nurturant and involved parenting, and behavior problems. *p < .05; **p < .01. Note. Standardized path coefficients are presented in the figure. Coefficients for the model predicting internalizing problems are in parentheses

Model fit was tested with multiple indices. Chi-square goodness of fit tests exact model fit, and a non-significant chi-square value supports model fit. Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) values below .06 support good model fit, and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) values above .95 indicate good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The model for externalizing problems demonstrated excellent model fit, with χ2(1) = .015, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00, and TLI = 1.05.

Based on the path coefficients, the model for externalizing problems supported direct paths from the risk index to nurturant and involved parenting and from nurturant and involved parenting to age 4 externalizing problems. In addition, all other direct paths were statistically significant except for the direct path from cumulative risk to age 4 externalizing problems. Predictors in the model explained 6.5% of the variance in nurturant and involved parenting and 27.1% of the variance in age 4 externalizing problems. To more closely examine the indirect prediction of age 4 externalizing problems from the risk index, we evaluated the indirect effect of the risk index on age 4 externalizing problems through nurturant and involved parenting. Following the procedures described by Shrout and Bolger (2002), a 95% confidence interval for the a × b indirect effect term of cumulative risk on externalizing problems through nurturant and involved parenting was estimated using bias-corrected bootstrap sampling methods over 1000 iterations. The confidence intervals (lower limit = .018 and upper limit = .063) for the standardized indirect effect of the risk index on age 4 externalizing problems did not overlap with zero, and the indirect effect was statistically significant (p < .01). Thus, the model supported an indirect effect of cumulative risk on age 4 externalizing problems through nurturant and involved parenting.

A separate model (see coefficients in parentheses in Figure 1) was created to examine predictors of internalizing problems at age 4. This model demonstrated excellent model fit, with χ2(1) = .002, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00, and TLI = 1.04, and supported direct paths from the risk index to nurturant and involved parenting and from nurturant and involved parenting to age 4 internalizing problems. The additional direct paths were also statistically significant except for the direct path from the risk index to age 4 internalizing problems. Predictors in the model explained 8.7% of the variance in nurturant and involved parenting and 32.4% of the variance in age 4 internalizing problems. Confidence intervals (lower limit = .008 and upper limit = .053) for the standardized indirect effect of the risk index on age 4 internalizing problems did not overlap with zero, and the indirect effect was statistically significant (p < .01). Thus, this model supported an indirect effect of cumulative risk on age 4 internalizing problems through nurturant and involved parenting.

Testing potential moderators

Because the magnitude of the relations among cumulative risk, parenting, and problem behaviors may have differed between the intervention and control groups or between ethnic minority and non-minority groups, steps were taken to examine group invariance in the overall path models. First, path models were tested that were identical to those in Figure 1 except for the elimination of intervention status as an exogenous predictor and the elimination of the non-significant path from cumulative risk to age 4 externalizing (or internalizing) problems in each model. An unconstrained model where path coefficients were allowed to vary across intervention and control group models was compared with a model where all path coefficients were constrained to be equal. The chi-square difference test was used to compare the chi-square and degrees of freedom for the two models to determine whether constraining the path coefficients worsened model fit (see Byrne, 2004). The constrained model did not significantly worsen model fit for the externalizing problems model (Δχ2 = 5.28, Δdf = 4, p > .05) or the internalizing problems model (Δχ2 = 5.29, Δdf = 4, p > .05). Thus, differences between intervention and control groups in the overall models of cumulative risk, parenting, and behavior problems were not supported. The same approach was used to test for differences in overall model fit for ethnic minority participants versus non-minority (i.e., white, non-Hispanic) participants. For minority status, the constrained model did not significantly worsen model fit for the externalizing problems model (Δχ2 = 2.83, Δdf = 4, p > .05) or the internalizing problems model (Δχ2 = 1.80, Δdf = 4, p > .05).

Discussion

This study supported cumulative risk in early childhood as a predictor of nurturant and involved parenting and nurturance and involvement as a predictor of later externalizing and internalizing problems. Parenting accounted for the indirect effect of cumulative risk on externalizing and internalizing problems. Path models simultaneously accounted for stability in behavior problems across early childhood, making these findings particularly robust. Furthermore, many families in this high-risk prevention research sample of young children endorsed multiple stressors. Thus, the cumulative risk index captured important stressors for families facing economic hardship, and the risk index was predictive of factors in early childhood that are indicators of later maladjustment and psychopathology. These findings add to a growing body of literature that has examined proximal aspects of the family environment to account for the relations between cumulative risk and child outcomes. The present work also extends recent work on cumulative risk and parenting by focusing on behavior problems as the indirect outcome of cumulative risk in an at-risk sample. More broadly, these findings are consistent with an ecological perspective on early childhood development where aspects of the broader family system influence the parent–child relationship and, subsequently, child adjustment (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006).

The family's broader context appeared to influence child externalizing and internalizing problems by reducing the primary caregiver's capacity to provide positive, attentive care. Increased contextual risk in conjunction with living in poverty may tax a caregiver's coping resources, thereby reducing parental nuturance and involvement. In early childhood, these relations may be especially important because curious and mobile toddlers require close supervision, and high levels of noncompliance warrant consistency in discipline. Also, toddlers prone to temperamental fearfulness, inhibition, or social withdrawal warrant parental support and nurturance to reduce the likelihood of later internalizing problems. Thus, caregivers’ capacity to cope with stress is a worthy moderator or mediator to examine in future research on the accumulation of risk factors and parenting of young children. Some parents may have inner resources to manage numerous stressors, allowing them to provide adequate or even exemplary parental care in the face of poverty and other contextual risk factors. However, the present findings suggest that parental resilience when facing high levels of family risk may be relatively rare.

As a noteworthy contrast, a study of school-age children demonstrated direct relations between a cumulative risk index and externalizing problems after accounting for the relation between harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior (Ackerman et al., 2004). It is possible that relations between cumulative risk and behavior problems are primarily indirect in early childhood, but direct associations between risk and behavior problems tend to emerge later in childhood. The parent–child relationship is the primary social context for toddlers and pre-schoolers, and parenting is a consistently robust predictor of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood (e.g., Campbell, Pierce, Moore, Marakovitz, & Newby, 1996; Feng et al., 2008). School-age children and adolescents are somewhat less directly reliant on caregivers and spend increasing time in extra-familial contexts. Thus, older children may experience more of the first-hand implications of accumulating risk factors such as a dangerous neighborhood combined with few material resources. Keeping these potential developmental changes in mind, the composition of a risk index will also influence whether relations between cumulative risk and child behavior problems are primarily direct or indirect. Many of the present study's contextual risk variables pertained to the primary caregiver's background (e.g., education, adolescent parenthood); therefore, the risk index was particularly likely to directly predict parenting.

Limitations

The present sample limits the degree to which results can be generalized. Nearly all of the families in this study experienced economic hardship as measured by their standing relative to the US poverty line at the age 2 assessment, and all families were recruited through WIC nutrition supplement programs for low-income families. Thus, the results are most directly applicable to families living at or near poverty. Relations between cumulative risk, parenting, and child adjustment may differ for middle-class or higher-income families.

The measurement of nurturant and involved parenting was based on a single independent observation. Furthermore, the use of a broad-based observation of parental involvement limited our ability to detect intervention effects on parenting in the present study; however, the main treatment outcome study demonstrated effects of the FCU on a latent factor specific to positive parenting (Dishion et al., in press). Also, child behavior ratings were based entirely on primary caregiver report, and the experience of risk may have biased their perception of child behavior.

Lastly, although the risk index was a relatively comprehensive measure of more distal risk factors, it did not include all risk factors that could influence child well-being such as relationship or residential instability (Ackerman et al., 2004). Also, a majority of the risk factors were naturally dichotomized, but a few risk factors were originally measured on a continuous scale which could attenuate the power to detect larger effects. The magnitude of the relations in the path models was modest, and the findings should only be generalized to populations facing similar contextual risks.

Implications and future directions

These findings have potentially important implications for social policy and prevention research with low-income families. The influence of parenting on problem behavior is well known from longitudinal and intervention studies. Our findings are noteworthy in showing that parenting is a key mechanism by which the effects of multiple stressors may be transmitted to young children. Even in the context of multiple contextual stressors, interventions that focus on promoting attentive and nurturant parenting are likely to be of key importance. When implementing evidence-based parenting interventions, policy-makers and practitioners are often concerned that multiply-stressed families find it hard to engage. These mediational findings complement those from recent parenting trials showing that subgroups of families with high levels of stress can respond equally as well to intervention as other families (e.g., Baydar, Reid & Webster-Stratton, 2003). In addition, families facing multiple contextual stressors may require support to directly reduce the family's stress burden.

Future research should track relations among cumulative risk, parenting, and child behavior problems longitudinally. Direct relations between cumulative risk and child behavior problems may emerge later when children spend less time with their parents and are more likely to experience the immediate negative impact of certain contextual risks. Although many of the cumulative risk indicators in the present study are typically stable, it would also be important to track change in contextual risk. Previous experimental and quasi-experimental research with older children demonstrates that altering a single risk factor (e.g., income level, neighborhood residence) can lead to reductions in psychopathology (Costello, Compton, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2003). Understanding how change in the level of risk influences parenting and child behavior can inform policy and intervention to prevent early-emerging forms of psychopathology.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant 5 R01 DA16110 from the National Institutes of Health to the third and fourth authors. We gratefully acknowledge the Early Steps staff and the families who participated in this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman BP, Brown ED, Izard CE. The relations between contextual risk, earned income, and the school adjustment of children from economically disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:204–216. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman BP, Izard CE, Schoff KM, Youngstrom EA, Kogos JL. Contextual risk, caregiver emotionality, and the problem behaviors of 6- and 7-year-old children from economically disadvantaged families. Child Development. 1999;70:1415–1427. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen MHM, Sroufe LA. When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 5.0 users’ guide. Smallwaters; Chicago: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C. The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for Head Start mothers. Child Development. 2003;74:1433–1453. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanz B, Schmidt MH, Esser G. Familial adversities and child psychiatric disorders. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology. 1991;32:939–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist. 1979;34:844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Lerner RM, editor. Theoretical models of human development. Handbook of child psychology. 6th edn Vol. 1. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS Graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:272–300. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. HOME inventory administration manual: Comprehensive edition. University of Arkansas; Little Rock, AR: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Pierce EW, Moore G, Marakovitz S, Newby K. Boys’ externalizing problems at elementary school age: Pathways from early behavior problems, maternal control, and family stress. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:701–719. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: A natural experiment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development. 1990;57:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Multiple-risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Group and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:469–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high risk indigent families: Outcomes of positive parenting and problem behaviors from ages 2 through 4 years. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: Development and validation of a neighborhood stress index. Health Psychology. 2002;21:254–262. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Shaw DS, Silk JS. Developmental trajectories of anxiety symptoms among boys across early and middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:32–47. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines A, Yoshikawa H. The effects of antipoverty programs on children's cumulative level of poverty-related risk. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:981–999. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, DeKlyen M. The role of attachment in the early development of disruptive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Brody G, Armistad L. Psychosocial adjustment of African American children in single-mother families: A test of three risk models. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, Black MM. Longitudinal predictors of competence among African American children: The role of distal and proximal risk factors. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23:237–266. [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Patterson GR. Parental management: Mediator of the effect of socioeconomic status on early delinquency. Criminology. 1990;28:301–323. [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Honorado E, Bush NR. Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of effortful control and social competence in preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Moving to opportunity: An experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1576–1582. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: Follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:179–207. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2004;69:1–129. doi: 10.1111/j.0037-976x.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Child–Parent Relationship Scale. 1995. Unpublished measure, University of Virginia.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E, Eyberg S, Ross A. The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1980;9:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Protective factors in children's responses to stress and disadvantage. In: Kent MW, Rolf JE, editors. Primary prevention in psychopathology. Vol. 8: Social competence in children. University Press of New England; Hanover, NH: 1979. pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, McDonough SC. Contextual contributors to the assessment of infant mental health. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental health assessment. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Oberklaid F, Pedlow R, Prior M. Risk indicators: Assessment of infancy pre-dictors of pre-school behavioural maladjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:609–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ, Gilliom M. A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:155–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1009599208790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the family check-up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Infant–caregiver attachment and patterns of adaptation in pre-school: The roots of maladaptation and competence. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Minnesota symposium in child psychology. Vol. 16. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. pp. 41–81. [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M, Bank L. Autoregressive effects in structural equation models: We see some problems. In: Gottman JM, editor. The analysis of change. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]