Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase BUR1/BUR2 appears to be the yeast ortholog of P-TEFb, which phosphorylates Ser2 of the RNA Pol II CTD, but the importance of BUR1/BUR2 in CTD phosphorylation is unclear. We show that BUR1/BUR2 is co-transcriptionally recruited to the 5′ end of ARG1 in a manner stimulated by interaction of the BUR1 C-terminus with CTD repeats phosphorylated on Ser5 by KIN28. Impairing BUR1/BUR2 function, or removing the CTD-interaction domain in BUR1, reduces Ser2 phosphorylation in bulk Pol II and eliminates the residual Ser2P in cells lacking the major Ser2 CTD kinase, CTK1. Impairing BUR1/BUR2 or CTK1 evokes a similar reduction of Ser2P in Pol II phosphorylated on Ser5, and in elongating Pol II near the ARG1 promoter. By contrast, CTK1 is responsible for the bulk of Ser2P in total Pol II and at promoter-distal sites. In addition to phosphorylating Ser2 near promoters, BUR1/BUR2 also stimulates Ser2P formation by CTK1 during transcription elongation.

Keywords: BUR1, BUR2, KIN28, RNA Polymerase, CTD, transcription elongation, histone methylation

The C-terminal repeat domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of RNA Pol II (RPB1) is a flexible scaffold for recruiting factors of mRNA processing, transcription elongation, or termination, whose binding is enhanced by phosphorylation of the CTD. The CTD is comprised of tandem repeats of the heptad Y1S2P3T4S5P6S7, phosphorylated on Ser2 and Ser5 during promoter clearance and elongation (Phatnani and Greenleaf, 2006). Ser5 CTD phosphorylation (Ser5P) in vivo is catalyzed by the cyclin-dependent kinase in TFIIH (CDK7; yeast KIN28), and Ser5P is most abundant near the 5′ ends of genes (Komarnitsky et al., 2000; Schroeder et al., 2000). Ser5P promotes recruitment of mRNA capping enzyme (Cho et al., 1997; Ho and Shuman, 1999) and nuclear cap-binding complex (CBC) (Wong et al., 2007) to nascent transcripts, and co-transcriptional recruitment of elongation factor Paf1C (Qiu et al., 2006), the histone H3-Lys4 methyltransferase complex (SET1/COMPASS) (Ng et al., 2003b), and histone acetyltransferase complex SAGA (Govind et al., 2007).

Subsequent to TFIIH function, the CTD is phosphorylated on Ser2 by CDK9/P-TEFb in mammals and the CTDK-I complex in yeast (containing CTK1as catalytic subunit) (Lee and Greenleaf, 1989; Marshall et al., 1996), and Ser2P is most abundant near the 3′ ends of genes (Cho et al., 2001; Komarnitsky et al., 2000). It is thought that P-TEFb releases elongating Pol II from pause sites induced by negative elongation factor complex NELF in concert with elongation factor DSIF (Peterlin and Price, 2006). Budding yeast lacks NELF, but it was shown that CTK1 stimulates co-transcriptional recruitment of SET2, for trimethylation of histone H3 on Lys36 (H3-K36Me3) (Krogan et al., 2003b; Li et al., 2003; Li et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2003). CTK1 also supports 3′ end formation by enhancing recruitment of cleavage/polyadenylation factors (Ahn et al., 2004; Licatalosi et al., 2002).

BUR1 and BUR2 are the catalytic and regulatory subunits of an essential CDK in budding yeast implicated in transcription elongation (Keogh et al., 2003; Yao et al., 2000). BUR1/BUR2 are most related in sequence to P-TEFb, and it was proposed that P-TEFb's functions are divided between CTK1 and BUR1 (Keogh et al., 2003; Wood and Shilatifard, 2006). However, evidence that BUR1/BUR2 contributes directly to Ser2 phosphorylation in vivo is lacking. Consistent with the notion that BUR1/BUR2 is a Ser2 CTD kinase, bur1 mutants are synthetically lethal with CTD truncations or ctk1Δ, but not with kin28 Ts- alleles, and ctk1Δ cells exhibit a weak Bur- phenotype (suppression of SUC2 UAS deletion). However, kin28-ts16 bur1-2 mutants are also barely viable (Lindstrom and Hartzog, 2001), and BUR1/BUR2 phosphorylated RPB1 in immune complexes only on Ser5 (Murray et al., 2001). Using recombinant CTD substrates, BUR1 phosphorylated Ser2 and Ser5, with some preference for Ser5, and was less active than CTK1 or KIN28. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of RPB1 associated with the PMA1 gene revealed no significant decreases in Ser5P or Ser2P in the catalytically defective bur1-23 mutant. Moreover, no decrease in bulk Ser5P, and only a slight decrease in Ser2P, were detected in bur1-23 extracts, and the Ser2P reduction was attributed to decreased amounts of elongating Pol II. Thus, BUR1's essential function seemed to involve phosphorylation of a substrate besides RPB1 (Keogh et al., 2003). On the other hand, it was reported that Ser2P is reduced only 50% by ctk1Δ during logarithmic growth, and CTK1 is responsible for the bulk of Ser2P only during diauxic growth (Patturajan et al., 1999). Thus, another Ser2 CTD kinase besides CTK1 must be active in exponentially growing cells.

BUR1 resembles P-TEFb in stimulating transcription elongation, but the mechanisms involved are unclear. bur1 mutations interact with defects in various elongation factors (Chu et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2001), and resemble other elongation factor mutations in conferring sensitivity to 6-azauracil (Keogh et al., 2003; Murray et al., 2001). BUR1 and BUR2 are found throughout coding sequences, and bur1-23 reduces Pol II occupancy in a manner indicating reduced processivity (Keogh et al., 2003). The finding that deleting subunits of histone deacetylase complex Rpd3-S suppresses the growth defects of bur1Δ and bur2Δ mutants (Keogh et al., 2005) suggests that histone hyperacetylation reduces the need for BUR1/BUR2 in elongation, perhaps by creating a less compact chromatin structure.

Another function of BUR1/BUR2 is to promote H2B monoubiquitination on Lys-123 (H2B-Ub) by RAD6/BRE1 and H3-K4 trimethylation by the SET1 complex (Laribee et al., 2005; Wood et al., 2005). Mutations in Paf1C decrease these modifications (Krogan et al., 2003a; Ng et al., 2003a; Wood et al., 2003), and considering that bur2Δ reduces Paf1C recruitment (Laribee et al., 2005; Qiu et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2005), the decrease in H2B-Ub and H3-K4Me3 in bur2Δ cells could be secondary to reduced Paf1C recruitment. There is also evidence that BUR1/BUR2 directly promotes H2B-Ub by phosphorylating RAD6 (Wood et al., 2005), but since bre1Δ cells lack both H2B-Ub and H3-K4Me3 and are viable, BUR1/BUR2 must have other important substrates besides RAD6. Interestingly, BUR2 also promotes SET2 recruitment and attendant H3-K36Me3 formation, particularly at the 5′ ends of genes (Chu et al., 2007).

We found previously that co-transcriptional recruitment of Paf1C by transcription factor GCN4 requires BUR2 in addition to elongation factor SPT4 and Ser5 CTD phosphorylation by KIN28 (Qiu et al., 2006). We began this study by investigating the mechanism of BUR1/BUR2 recruitment and found evidence that BUR2 recruitment to the ARG1 gene is enhanced by KIN28. Pursuing this, we identified a CTD-interaction domain (CID) dependent on Ser5P located in the C-terminal region of BUR1, which stimulates its recruitment to the 5′ end of ARG1. Given that BUR2 promotes H3-K36Me3 formation at 5′ ends (Chu et al., 2007), and that SET2 recruitment is stimulated by Ser2P generated by CTK1, we asked whether BUR1/BUR2 contributes to Ser2P formation near promoters. Studying a bur1 allele that allows chemical inhibition of kinase activity, we show that BUR1/BUR2 produces the residual Ser2P remaining when CTK1 is inactivated. We also found that BUR1/BUR2 contributes a significant proportion of Ser2P in elongating Pol II molecules phosphorylated on Ser5 and located near the promoter. We propose that BUR1/BUR2 is recruited to CTD repeats phosphorylated on Ser5 to augment Ser2 phosphorylation by CTK1 early in the transcription cycle.

Results

Co-transcriptional recruitment of BUR1/BUR2 is enhanced by KIN28

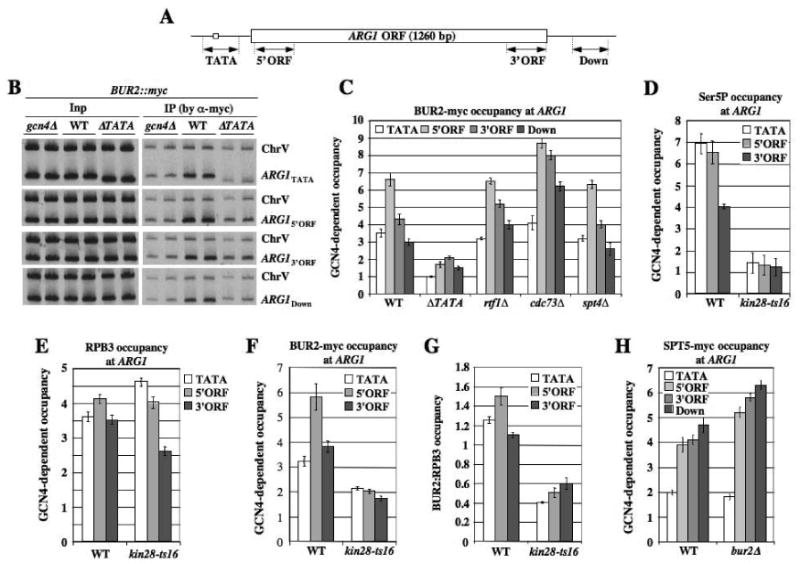

To study the mechanism of BUR1/BUR2 recruitment by GCN4, we conducted ChIP analysis of myc-tagged BUR2 binding at the ARG1 gene in WT and gcn4Δ strains during isoleucine-valine starvation (imposed with the inhibitor sulfometuron) when GCN4 is induced. We normalized BUR2-myc binding at ARG1 for non-specific binding to intergenic sequences on chromosome V (Komarnitsky et al., 2000), and for that seen in gcn4Δ cells, to calculate GCN4-dependent BUR2 occupancy at ARG1. There is strong GCN4-dependent recruitment of BUR2 to the ARG1 promoter (TATA region), sequences at the 5′ or 3′ end of the coding sequence (5′ and 3′ ORF, respectively), and transcribed sequences located downstream of the ORF (Down) (Fig. 1B, WT vs. gcn4Δ; Fig. 1C, WT). BUR2 occupancy is generally higher in the ORF versus TATA or downstream sequences, and moderately higher at the 5′ versus 3′ end of the ORF (Fig. 1C & 1F). Moderate enrichment of BUR1-myc at the 5′ end of GAL1 also was observed during induction by galactose (Supplementary Fig. S1). As this 5′ bias was not observed at ARG1 for SPT5 (Fig. 1H) or CTK1 (Fig. 4F), it suggested that BUR1/BUR2 is recruited early in the elongation phase.

Fig. 1. Co-transcriptional recruitment of BUR2 to ARG1 is enhanced by KIN28.

(A) ARG1 locus showing regions subjected to ChIP analysis. (B, C) ChIP analysis of BUR2-myc binding at ARG1. BUR2::myc strains with the indicated mutations (HQY1002, HQY1003, HQY1051, HQY1004, HQY1007, HQY1008) were cultured in SC medium lacking Ile and Val and treated with sulfometuron (SM) for 30 min to induce GCN4, then subjected to ChIP analysis with myc antibodies. DNA extracted from immunoprecipitates (IP) and input chromatin (Inp) samples was subjected to PCR in the presence of [33P]-dATP with the appropriate primers to amplify radiolabeled fragments of ARG1 shown in (A) or a control fragment (ChrV). PCR products were resolved by PAGE and visualized by autoradiography, with representative results shown in (B), and quantified with a phosphorimager. The ratios of ARG1 to ChrV signals in IP samples were normalized for the corresponding ratios for Inp samples. The resulting values for the GCN4 strains were normalized to the corresponding values for the gcn4Δ strain to yield GCN4-dependent occupancies plotted in (C). (D-G)BUR2::myc strains (HQY1052, HQY1055, HQY1053) were grown at 25°C to OD600 of ∼0.6, transferred to 37°C for 30 min and treated with SM for another 30 min at 37°C. ChIP analysis was conducted as described above using H14 antibody (D), RPB3 antibody (E), or myc antibody (F). Values for BUR2-myc in (F) were normalized to those for RPB3 in (E) to calculate the ratios in (G). (H) SPT5::myc strains (HQY971, HQY973, HQY1040) were subjected to ChIP analysis as above. The error bars in this and all subsequent figures correspond to standard errors of the mean.

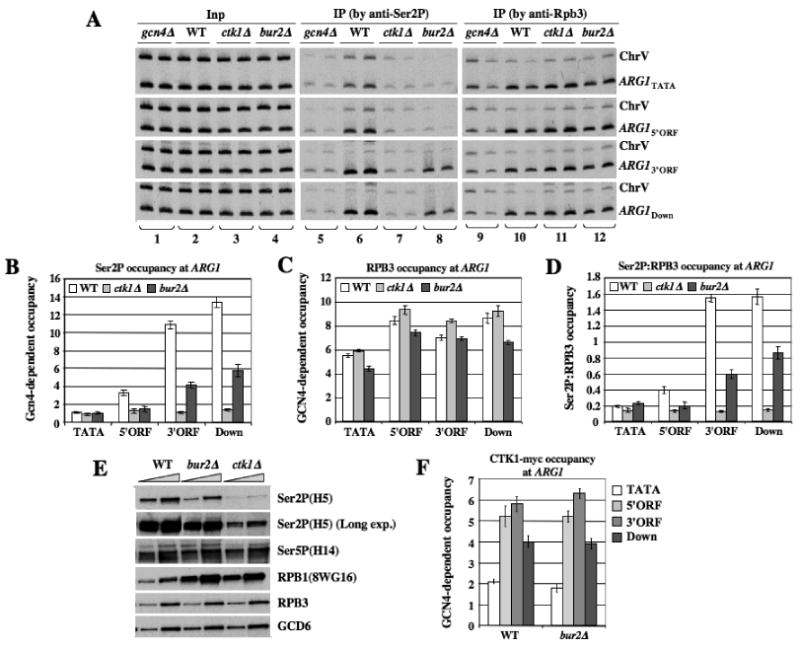

Figure 4. bur2Δ reduces Ser2P occupancy at the 5′ end of ARG1.

(A-D) Strains with the indicated mutations (249, BY4741, 7028, HQY1038) were subjected to ChIP analysis as described in Fig.1 using antibodies for Ser2P or RPB3, with representative results shown in (A). (B-C) GCN4-dependent Ser2P or RPB3 occupancies were calculated as described in Fig. 1 (ie. normalizing for ChrV signals) and ratios of these occupancies are plotted in (D). (E) WCEs of strains with the indicated mutations prepared under denaturing conditions (TCA extraction) were subjected to Western analysis with the indicated antibodies against Ser2P, Ser5P, or hypophosphorylated RPB1 (8WG16), or against RPB3 or GCD6. (F) CTK1::myc strains (HQY1010, HQY1012, HQY1108) were subjected to ChIP analysis as in Fig.1.

We have shown that deleting the ARG1 TATA element (ΔTATA) reduces occupancies of SPT4, Paf1C and SAGA, in addition to Pol II itself, in ARG1 coding sequences, indicating that their recruitment to the ORF requires transcription (Govind et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2006). Likewise, we found that deleting TATA reduces BUR2 occupancies across ARG1 (Fig. 1B-C, WT vs. ΔTATA). We then asked whether inactivating Ser5 kinase KIN28 reduces BUR2 association with transcribed ARG1 sequences. As expected, in WT cells, Ser5P occupancy is higher in the promoter and 5′ORF than in the 3′ORF, and Ser5P is reduced in kin28-ts16 cells at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 1D). This last effect is associated with a moderate decline in RPB3 occupancy at the 3′ORF, but not in the promoter or 5′ORF (Fig. 1E), consistent with decreased promoter clearance by Pol II (Sims et al., 2004). Importantly, BUR2 occupancy is reduced more than that of RPB3 (Fig. 1F), and the BUR2:RPB3 ratio (panel G) is reduced at all locations in kin28-ts16 cells. These findings suggest that co-transcriptional recruitment of BUR1/BUR2 is stimulated by Ser5 phosphorylation by KIN28.

ChIP analysis of the rtf1Δ and cdc73Δ mutants, lacking Paf1C subunits necessary for Paf1C recruitment (Qiu et al., 2006), revealed no decrease in BUR2 occupancy (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained for an spt4Δ mutant (Fig. 1C) that exhibits reduced Paf1C recruitment (Qiu et al., 2006). Thus, BUR1/BUR2 recruitment is independent of Paf1C and SPT4. ChIP analysis reveals that BUR2 is dispensable for recruitment of SPT5 (Fig. 1H), and we showed previously that SPT4 recruitment was unaffected by kin28-ts16 (Qiu et al., 2006). Together, these results suggest that SPT4/SPT5 and BUR1/BUR2 are recruited independently by elongating Pol II, and thus make separate contributions to Paf1C recruitment, and that BUR1/BUR2 recruitment is stimulated by Ser5P.

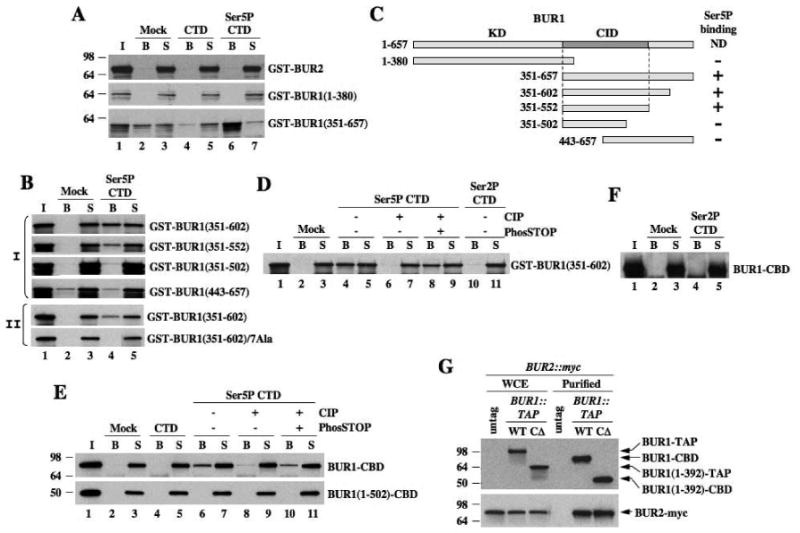

The C-terminal region of BUR1 binds Ser5P and promotes BUR1/BUR2 recruitment

We asked next whether BUR1 or BUR2 contains a CID that could account for the stimulatory effect of KIN28 on BUR2 recruitment. Indeed, the C-terminal half of BUR1 fused to GST binds to a synthetic peptide of four CTD repeats phosphorylated on Ser5 (Ser5P-CTD), but no binding above background to the cognate unphosphorylated peptide (Fig. 2A). The N-terminal half of BUR1 and full-length BUR2 showed no binding to either peptide (Fig. 2A). By testing additional truncations of BUR1, we identified residues 351-552 as the minimal region harboring a functional CID (Fig. 2B-C). We repeated the assays with BUR1(351-602) after treating the peptide with calf intestine phosphatase (CIP) in the presence or absence of phosphatase inhibitor PhosSTOP. Treatment with CIP alone, but not in the presence of PhosSTOP, eliminated binding of BUR1(351-602) to Ser5P peptides (Fig. 2D, cf. lanes 6-7 vs. 8-9). We observed no binding to a synthetic peptide phosphorylated on Ser2 (Fig. 2D). Hence, the BUR1 CID binds to CTD repeats in a manner stimulated by Ser5 phosphorylation.

Fig. 2. BUR1 binds to Ser5P-CTD peptides.

(A-D) Biotinylated CTD peptides (1.5μg) phosphorylated on Ser5 (Ser5P-CTD) or unphosphorylated (CTD) were adsorbed to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. Recombinant GST-BUR2 or GST-BUR1 fragments were incubated with beads alone (Mock) or beads bearing peptides at 4°C. Bound (B) and unbound proteins in supernatant (S) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis with myc antibody. (C) Schematic summarizing results in (A-B). (E-F) BUR1-CBD and BUR1(1-502)-CBD purified from yeast were used for peptide binding assays as above and detected using anti-TAP antibodies. In (D-E), immobilized peptides were treated with CIP in the presence or absence of PhosSTOP prior to incubation with proteins. (G) BUR1-TAP and BUR1-CΔ-TAP were purified from BUR2::myc strains and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western analysis, along with the starting extracts (WCE), using antibodies against TAP (upper panel) and myc (lower panel).

To pinpoint BUR1 residues involved in CTD binding, we identified amino acid positions highly conserved among BUR1 orthologs from different fungi, and made alanine substitutions in a cluster of 7 residues located just C-terminal to the kinase domain (Fig. S2). This 7Ala substitution abolished binding of GST-BUR1(351-602) to Ser5P peptides (Fig. 2B-II), implicating these conserved residues in CTD binding. We found no obvious sequence similarity between the BUR1 CID and other known CIDs (Meinhart et al., 2005), suggesting that BUR1 contains a distinct CTD binding motif.

We asked next whether native BUR1-BUR2 complex can bind to Ser5P. TAP-tagged BUR1 proteins were purified on IgG resin, removing the protein A moiety with TEV protease. The resulting proteins, retaining the calmodulin binding domain (CBD), were tested for binding to CTD peptides. Full-length BUR1-CBD bound to untreated, but not to CIP-treated, Ser5P peptides (Fig. 2E), nor to Ser2P peptides (Fig. 2F). C-terminally truncated protein BUR1(1-502)-CBD did not bind Ser5P nor unphosphorylated peptides (Fig. 2E). Equal amounts of BUR2-myc co-purified with full-length BUR1-CBD and a C-terminally truncated protein lacking residues 393-657 (previously dubbed bur1-CΔ) (Fig. 2G), confirming that the C-terminal half of BUR1 is dispensable for interaction with BUR2 (Keogh et al., 2003). These results indicate that native BUR1/BUR2 interacts with the Ser5-phosphorylated CTD dependent on the BUR1 CID.

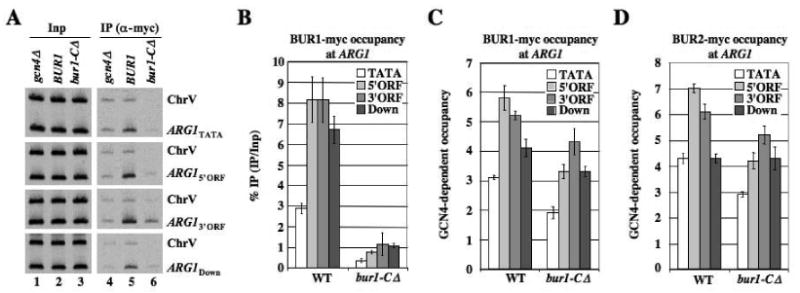

The bur1-CΔ mutation confers cold-sensitive growth, the Bur- phenotype, and is synthetically lethal with ctk1Δ, and it reduces BUR1 recruitment to ADH1 and PMA1 by a factor of ≈2 (Keogh et al., 2003). Consistently, bur1-CΔ decreased GCN4-dependent occupancy of BUR1 at ARG1. This was clearly evident from reduced precipitation of ARG1 sequences relative to their input levels in chromatin (Fig. 3A, cf. lanes 5-6 vs. 2-3), and after normalizing for BUR1 occupancies in gcn4Δ cells (Fig. 3B). ChIP signals for ChrV also were reduced in the bur1-CΔ strain (Fig. 3A), however, which might reflect a general reduction in chromatin association by bur1-CΔ protein. (The decrease in chromatin fragments specifically precipitated with bur1-CΔ would reduce the amount of ChrV fragments nonspecifically trapped in immune complexes.) Although normalization of the ChIP signals for binding at ARG1 versus ChrV dampens the calculated reduction in BUR1 occupancy produced by the -CΔ mutation, it is still significantly reduced across ARG1 (Fig. 3C). Because bur1-CΔ occupancy is more substantially reduced at the 5′ end of ARG1, it now peaks at the 3′ rather than 5′ end of the gene (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained for BUR2 in the bur1-CΔ background (Fig. 3D). These changes in BUR1 and BUR2 distribution across ARG1 conferred by bur1-CΔ establish the significance of the 5′ end enrichment of wild-type BUR1/BUR2 noted above. The -CΔ mutation does not reduce the steady-state level of BUR1 in cell extracts (data not shown). We conclude that bur1-CΔ impairs association of BUR1/BUR2 with elongating Pol II molecules, particularly those near the promoter. This fits with our finding that BUR1/BUR2 recruitment is enhanced by Ser5P, which also peaks at the 5′ end of ARG1 (Fig. 1D). Hence, interaction of the BUR1 CID with Ser5 phosphorylated Pol II stimulates recruitment of the BUR1/BUR2 complex at promoter-proximal locations.

Fig. 3. The BUR1 CID enhances BUR1/BUR2 recruitment to the ARG1 5′ ORF in vivo.

(A-C) BUR1::myc strains (HQY1188, HQY1223, HQY1280) and (D) BUR2::myc strains (HQY1002, HQY1003, HQY1268) were subjected to ChIP analysis as described in Fig.1, with representative results shown in (A), and GCN4-dependent occupancies plotted in (C-D). (B) gives the ratio of IP to Inp signals for ARG1, normalized to the corresponding values for the gcn4Δ strain, without normalizing for the ChrV signals.

Recruitment of BUR1/BUR2 by Ser5P elevates Ser2 phosphorylation in vivo

Having shown previously that KIN28 stimulates recruitment of Paf1C to ARG1, we asked whether BUR1/BUR2 also promotes Paf1C recruitment as a CTD kinase by enhancing Ser5P formation. Instead, ChIP analysis with (H14) antibodies specific for Ser5P revealed that bur2Δ cells exhibit higher levels of Ser5P at ARG1 (Fig. S3A). The bur2Δ mutant also displays slightly increased Pol II (RPB3) occupancy in the ORF (Fig, S3B), and after normalizing for this effect, the Ser5P:RPB3 ratio is found to increase, particularly near the 5′ end of ARG1, in bur2Δ cells (Fig. S3A-C). Interestingly, deletion of CTK1, the major Ser2P-CTD kinase, had a similar effect of increasing the Ser5P occupancy and Ser5P:RPB3 ratio at ARG1 (Fig. S3D-F).

bur2Δ also resembles ctk1Δ in reducing SET2 recruitment and H3-K36Me3, except that in bur2Δ cells these defects are more pronounced at the 5′ ends of genes (Chu et al., 2007). Combining this fact with the sequence similarity between BUR1 and P-TEFb, and genetic similarities between CTK1 and BUR1, we reasoned that BUR1/BUR2 might promote Ser2 CTD phosphorylation, especially at the 5′ ends of genes. To test this, we conducted ChIP analysis of Ser2P at ARG1 in WT, gcn4Δ and bur2Δ strains. Comparing WT and gcn4Δ cells revealed that GCN4-dependent Ser2P occupancy increases progressively from the TATA, through the ORF, to sequences downstream of ARG1 in WT cells (Fig. 4A, lanes 6), as would be expected (Cho et al., 2001; Komarnitsky et al., 2000). Importantly, bur2Δ nearly eliminated Ser2P occupancy in the promoter and 5′ORF, and reduced Ser2P in the 3′ ORF (Fig. 4A, lanes 8), while having little effect on total Pol II (RPB3) occupancy (Fig. 4A, lanes 12 vs. 10). These results suggest that bur2Δ reduces the Ser2P content of elongating Pol II, particularly near the promoter, at ARG1. The ChIP signals for Ser2P at the ChrV sequences were also reduced in the bur2Δ strain (Fig. 4A, lanes 8 vs. 6), which could reflect a general reduction in chromatin association of Ser2-phosphorylated Pol II. Thus, normalization of the Ser2P ChIP signals at ARG1 with those measured for ChrV dampens the reduction in GCN4-dependent Ser2P occupancy produced by bur2Δ. Nevertheless, the normalized GCN4-dependent occupancies of Ser2P and RPB3 still lead to significant decreases in Ser2P:RPB3 ratios at the 5′ and 3′ ends of ARG1 in bur2Δ cells (Fig. 4B-D).

We found that eliminating CTK1, the major Ser2 CTD kinase, greatly reduces Ser2P levels across ARG1 (Fig. 4A, lanes 7 vs. 6). Moreover, ctk1Δ has a much greater effect than bur2Δ on the Ser2P:RPB3 ratio at the 3′ end of ARG1, reducing it there by a factor of ∼10 but only by a factor of ∼3 at the 5′ end of the gene (Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that BUR1 and CTK1 make similar contributions to the Ser2P content of Pol II molecules located near the promoter, whereas CTK1 contributes the bulk of Ser2P at promoter-distal locations. The diminished Ser2P occupancy in bur2Δ cells does not result from decreased CTK1 occupancy at ARG1 (Fig. 4F).

To provide evidence that BUR1/BUR2 is required for a proportion of Ser2P throughout the genome, we measured Ser2P levels in bulk RPB1 by Western analysis of WCEs. As expected, ctk1Δ strongly reduces total Ser2P (detected with antibody H5) while increasing hypophosphorylated RPB1 (detected with antibody 8WG16), while Ser5P is relatively unchanged (Fig. 4E). A darker exposure confirms that Ser2P is not abolished in ctk1Δ cells. Importantly, bur2Δ also reduces Ser2P and increases hypophosphorylated RPB1, but the reduction in Ser2P was smaller than for ctk1Δ (Fig. 4E, bur2Δ). These findings support the idea that BUR1/BUR2 is required for Ser2 CTD phosphorylation of a subset of Pol II molecules or CTD repeats.

Having found that the bur1-CΔ mutation reduces recruitment of BUR1/BUR2 to the 5′ end of ARG1 (Fig. 3A-D), we predicted that -CΔ should diminish the cellular Ser2P level. The Western analysis in Figs. 5A-B confirmed this expectation for -CΔ and also extended it to include the 7Ala substitution in the BUR1 CID that abolished binding to Ser5P peptides. These results imply that recruitment of BUR1/BUR2 to the 5′ ends of genes by association of the BUR1 CID with Ser5P enhances Ser2 CTD phosphorylation in bulk Pol II.

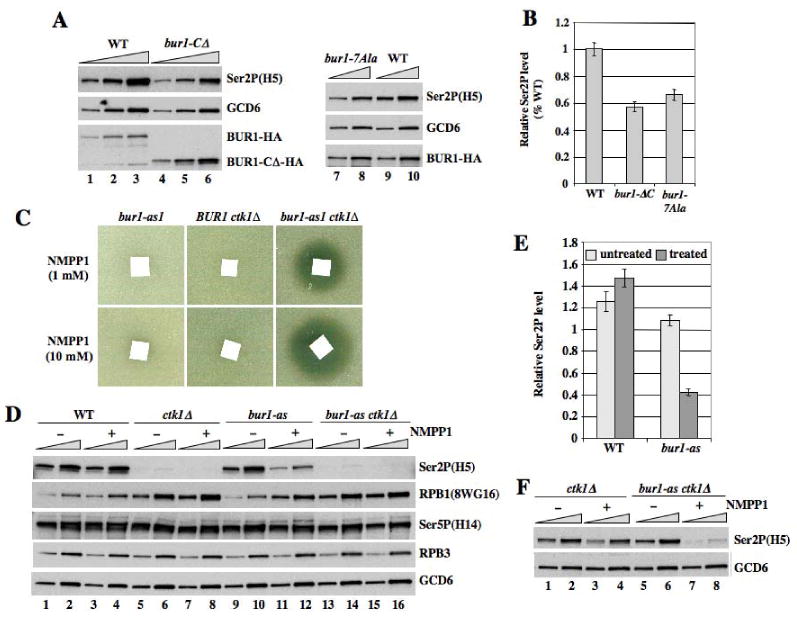

Fig. 5. Chemical inactivation of the bur1-as product reduces Ser2P in bulk Pol II.

(A-B) Western analysis of WCEs prepared under denaturing conditions from WT, bur1-ΔC, and bur1-7Ala strains (HQY1269, HQY1270, H1299), using antibodies against the indicated proteins. Quantification of results for Ser2P normalized for GCD6 is shown in (B). (C) Strains HQY1190, HQY1221 and HQY1220 with the indicated mutations were plated in soft agar containing 3 μl of 1 mM or 10 mM NM-PP1 applied to a filter paper square. (D-F) Strains from (C) and HQY1223, with the indicated mutations, untreated (-) or treated (+) with NMPP1, were subjected to Western analysis as in (A-B). 12.5-25-fold amounts of WCEs for the ctk1Δ and bur1-as ctk1Δ strains in (D) were examined in (F).

CTK1 and BUR1/BUR2 make additive contributions to Ser2P on elongating Pol II in vivo

From quantification of the Western data in Fig. 4E, we calculated that ctk1Δ reduces total Ser2P by ∼90% (Fig. S4A). Thus, one might predict that BUR1/BUR2 would contribute only ∼10% of the total Ser2P, whereas we calculated a 50% reduction in Ser2P for bur2Δ cells (Fig. S4A). A similar paradox was evident in the ChIP data above when considering the relative contributions of CTK1 and BUR1/BUR2 to Ser2P at the 3′ end of ARG1 (Fig. 4A-B). It is possible that a proportion of Ser2P in the extract or chromatin is below the detection limit of Western and ChIP analysis, leading us to overestimate the contribution of CTK1 to Ser2P formation (see Fig. S4B for details). While this might explain some of the discrepancy, it appears that BUR1/BUR2 also contributes indirectly to Ser2P by stimulating CTK1 function. Assuming that BUR1/BUR2 is a Ser2 CTD kinase, its phosphorylation of a limited number of CTD repeats might enhance the ability of CTK1 to phosphorylate Ser2 throughout the CTD, so that bur2Δ would reduce the functions of both Ser2 CTD kinases. A third possibility, suggested previously (Keogh et al., 2003), is that bur2Δ reduces Ser2P only indirectly by reducing the amount of elongating Pol II available for Ser2 phosphorylation by CTK1. According to this last explanation, inactivating BUR1/BUR2 should have no effect on Ser2P levels in a ctk1Δ background. This prediction has been difficult to test because bur1 Ts- and bur2Δ mutations are synthetically lethal with ctk1Δ (Keogh et al., 2003; Murray et al., 2001; Xiao et al., 2007). Hence, we constructed an analog-sensitive (as) allele, harboring a Gly substitution of residue Leu-149 in the kinase domain (Bishop et al., 2001), to permit chemical inhibition of BUR1 kinase activity in a ctk1Δ background.

The bur1-as mutation renders the autokinase activity of immunopurified BUR1/BUR2 highly sensitive to the ATP analog NM-PP1, with essentially complete inhibition at 0.5 μM NM-PP1, while the activities of WT BUR1/BUR2 and CTK1 were unaffected by much higher analog concentrations (Fig. S5). Whereas growth of bur1-as CTK1 cells is insensitive to high concentrations of inhibitor, NM-PP1 strongly inhibits growth of a bur1-as ctk1Δ double mutant on solid medium (Fig. 5C) and doubled the cell division time in liquid medium when added at 20 μM (data not shown). This fits with the idea that CTK1 and BUR1/BUR2 kinase functions are partially redundant in vivo. The fact that NM-PP1 does not inhibit growth of the bur1-as single mutant, even though BUR1 is essential, suggests that NM-PP1 does not fully inactivate BUR1 kinase activity in vivo.

Similar to our findings on bur2Δ, treatment of bur1-as cells with NM-PP1 reduced Ser2P in bulk RPB1 and increased the amount of hypophosphorylated RPB1 (Fig. 5D, lanes 11-12 vs. 9-10 for Ser2P and RPB1 panels; quantification in Fig. 5E). Nevertheless, ctk1Δ still elicits a greater decrease in Ser2P levels compared to chemical inhibition of the bur1-as single mutant (Fig. 5D, lanes 11-12 vs. 7-8). Importantly, NM-PP1 treatment of the bur1-as ctk1Δ double mutant led to a further decline in Ser2P compared to the ctk1Δ single mutant, which became evident after increasing the amount of extract loaded per lane to facilitate detection of low-level Ser2P in ctk1Δ cells (Fig. 5F). These results provide direct evidence that BUR1 promotes Ser2P formation, at least partly, by a mechanism independent of CTK1. ChIP analysis of the bur1-as mutant produced results consistent with those presented above for bur2Δ cells. Treating bur1-as, but not WT, cells with NMPP1 reduced Ser2P occupancy at ARG1 (Fig. S6A-B) to an extent that cannot be explained by decreased Pol II occupancy (Fig. S6C-E). Thus, chemical inhibition of BUR1 lowers the Ser2P content of elongating Pol II molecules associated with ARG1 coding sequences.

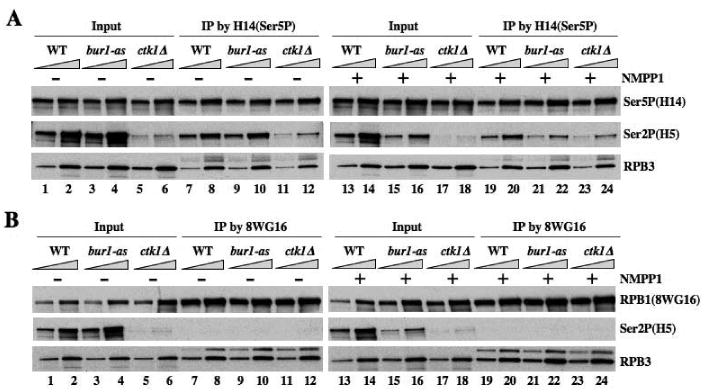

We sought to eliminate by an independent approach the possibility that inhibition of BUR1 reduces Ser2P levels only by decreasing the pool of elongating Pol II. We first used H14 antibodies to immunoprecipitate Ser5-phosphorylated RPB1, which should represent Pol II molecules engaged in promoter clearance or elongation, and probed them with H5 antibodies for Ser2P. The ctk1Δ mutation lowers the yield of Ser2P in H14-immunoprecipitated RPB1, in the presence or absence of NM-PP1 (Fig. 6A, Ser2P panel, cf. lanes 11-12 vs. 7-8 and 23-24 vs 19-20). This fits with the prediction that many Pol II molecules phosphorylated on Ser5 also contain Ser2P, and the expectation that CTK1 contributes to this Ser2 phosphorylation (Phatnani and Greenleaf, 2006; Wood and Shilatifard, 2006). Importantly, the analog-treated bur1-as single mutant also shows reduced Ser2P in H14-immunoprecipitated RPB1, but only when treated with NM-PP1 (Fig. 6A, Ser2P, lanes 21-22 vs. 19-20 and 9-10 vs. 7-8). As expected, Ser2P is essentially undetectable in RPB1 immunoprecipitated with 8WG16 antibodies specific for hypophosphorylated CTD (Fig. 6B). By the same approach, we found that bur2Δ also reduces the Ser2P content of immunoprecipitated RPB1 phosphorylated on Ser5 (Fig. S7). It could be argued that inactivation of BUR1/BUR2 reduces Ser2P in Pol II phosphorylated on Ser5 indirectly by preventing promoter escape by Pol II. This seems unlikely, however, considering that bur2Δ does not reduce the occupancy of Ser5P in the ARG1 coding sequences (Fig. S3A). Hence, CTK1 and BUR1 both contribute to Ser2P in elongating Pol II molecules hyperphosphorylated on Ser5.

Fig. 6. Inactivation of BUR1 reduces Ser2P in elongating Pol II.

(A-B) WCEs from strains with the indicated mutations (HQY1223, HQY1221, HQY1190), untreated (-) or treated (+) with NMPP1, were prepared under non-denaturing conditions and immunoprecipitated with H14 (A) or 8WG16 antibodies (B) and immune complexes were probed with antibodies against the indicated proteins.

The reduction of Ser2P in immunoprecipitated Ser5-phosphorylated RPB1 produced by ctk1Δ is only slightly greater than that conferred by bur1-as in the presence of NM-PP1, whereas ctk1Δ has a much greater effect than bur1-as on Ser2P in bulk RPB1 (Fig. 6A; compare Ser2P signals in lanes 23-24 vs. 21-22 with lanes 17-18 vs. 15-16.) These comparisons suggest that BUR1 makes a larger contribution to Ser2 phosphorylation of Pol II molecules hyperphosphorylated on Ser5 compared to hypo- or unphosphorylated Pol II. By contrast, CTK1 makes a proportionately larger contribution to Ser2 phosphorylation of Pol II that is hypophosphorylated on Ser5.

Discussion

We have provided strong evidence that BUR1/BUR2 is required for high-level Ser2 phosphorylation in vivo, and that it contributes a proportion of Ser2P independently of the major Ser2 CTD kinase CTK1, particularly near promoters. We found that impairing BUR1 activity by eliminating BUR2 or chemically inhibiting the bur1-as product reduces Ser2P with an attendant increase in hypophosphorylated RPB1 in bulk Pol II. The bur2Δ and bur1-as mutations also decrease Ser2P occupancy in the ARG1 coding sequences without a commensurate reduction in occupancy of elongating Pol II itself. BUR1/BUR2 makes a smaller contribution than CTK1 to the overall level of Ser2P in bulk Pol II. However, bur2Δ, bur1-as and ctk1Δ have comparable effects in reducing Ser2P at the 5′ end of ARG1, whereas ctk1Δ evokes a stronger decrease in Ser2P at the 3′ end of the gene. Moreover, bur2Δ, bur1-as and ctk1Δ all conferred strong reductions in Ser2P in the pool of bulk Pol II hyperphosphorylated on Ser5 (immunoprecipitated with H14 antibodies). These results suggest that BUR1/BUR2 makes a substantial contribution to Ser2P in Pol II molecules already phosphorylated on Ser5 and located near the promoter, whereas CTK1 is responsible for the majority of Ser2P and is the predominant Ser2 CTD kinase distal to the promoter.

Although a decrease in Ser2P at PMA1 was noted previously in bur1-23 cells, it was attributed to decreased occupancy of Pol II itself at this gene. In addition, while Ser2P in bulk Pol II was reduced in a bur2Δ strain, this was judged to be an indirect consequence of lower levels of elongating Pol II (Keogh et al., 2003). Our findings suggest that BUR1/BUR2's contribution to Ser2P is not limited to its role in producing elongating Pol II molecules as substrates for CTK1. First, Pol II occupancy in the ARG1 ORF is not reduced in our bur2Δ strain, such that the Ser2P:RPB3 ratio at this gene is diminished in this mutant. Second, the Ser2P content of Pol II molecules phosphoryated on Ser5P, which should represent Pol II molecules engaged in elongation, is reduced in both bur1-as and bur2Δ mutants. Most importantly, inactivation of the bur1-as mutant in ctk1Δ cells eliminated the residual Ser2P in bulk Pol II that remains after eliminating CTK1 alone, proving that BUR1 can promote Ser2P formation independently of CTK1.

Combining these findings with the sequence similarity of BUR1 to P-TEFb, and genetic similarities between BUR1 and CTK1, leads us to propose that BUR1/BUR2 functions as a Ser2 CTD kinase in vivo. Nevertheless, a proportion of the decline in Ser2P evoked by bur2Δ and bur1-as mutations, at least at promoter-distal locations, probably results indirectly from reduced phosphorylation by CTK1. This follows from our finding that ctk1Δ eliminates ≈90% of the detectable Ser2P in bulk Pol II, yet inactivating BUR1/BUR2 eliminates much more than 10% of the total Ser2P. One possibility is that Ser2 phosphorylation of a limited number of CTD repeats by BUR1/BUR2 near the promoter can enhance the ability of CTK1 to phosphorylate Ser2 throughout the CTD, and counteract the Ser2P phosphatase, as elongation proceeds downstream. This hypothesis is difficult to test in vitro because steady-state kinetic analysis of CTK1 phosphorylation of the full-length CTD is problematic (Jones et al., 2004), and it would impossible at present to reconstitute the extent or pattern of partial CTD phosphorylation by BUR1/BUR2 that prevails in vivo. It is also possible that phosphorylation of other, unknown substrates of BUR1/BUR2 indirectly stimulates Ser2P phosphorylation by CTK1 in vivo.

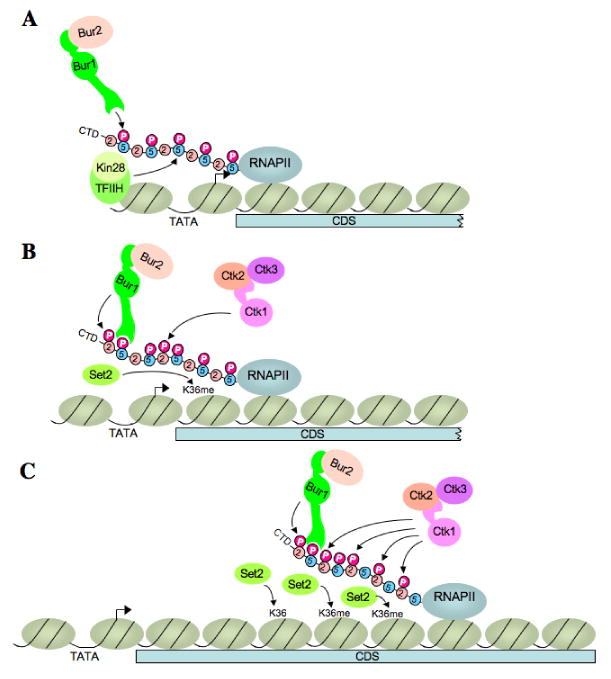

Our findings that bur2Δ and bur1-as produce a substantial decrease in Ser2P at the 5′ end of ARG1, and in Pol II hyperphosphorylated on Ser5, fit with our observations that BUR1/BUR2 occupancy peaks near the ARG1 and GAL1 promoters, and our discovery that recruitment of BUR1/BUR2 is stimulated by the Ser5 CTD kinase KIN28. We discovered that the C-terminal half of BUR1 contains a CID capable of binding Ser5P peptides in vitro. Removing this CID from BUR1 by the −CΔ mutation preferentially reduces BUR1/BUR2 occupancies at the 5′ end of the ARG1 ORF, so that they peak in the 3′ end of the ORF. The −CΔ and -7Ala substitutions in the BUR1 CID also reduce the level of Ser2P in bulk Pol II. Hence, we propose that binding of the BUR1 CID to Ser5P, generated by KIN28, stimulates BUR1/BUR2 recruitment to the 5′ end of the gene (Fig. 7A), enhancing its ability to phosphorylate Ser2 early in the elongation cycle (Fig. 7B). We envision a cascade of CTD phosphorylation, wherein Ser5 phosphorylation by KIN28 enhances Ser2 phosphorylation by BUR1/BUR2 in the same or adjoining CTD repeats of promoter-proximal Pol II, which stimulates or gives way to Ser2 phosphorylation by CTK1 further downstream in the coding sequences (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7. Schematic model of Ser5P-stimulated BUR1/BUR2 recruitment and differential contributions of BUR1/BUR2 and CTK1 to Ser2P and H3-K36Me3 formation at 5′ and 3′ ends of a coding sequence.

(A) BUR1/BUR2 is recruited to the CTD phosphorylated on Ser5 by KIN28 at or near the promoter. (B) Recruited BUR1/BUR2 phosphorylates Ser2 near the promoter, enhancing H3-K36Me3 formation by SET2. It is unknown whether Pol II pausing early in the coding sequence (CDS) is required to facilitate BUR1/BUR2 function. BUR1/BUR2 and CTK1 make roughly equivalent contributions to Ser2P formation at this location. (C) As elongation proceeds downstream, CTK1 makes an increasingly larger contribution to Ser2P formation and attendant H3-K36Me3 formation by SET2. Because the occupancies of both kinases remain high at the 3′ end, either CTK1 becomes more active, or BUR1/BUR2 activity declines, as elongation proceeds. See text for more details.

In addition to stimulating BUR1/BUR2 recruitment, Ser5 phosphorylation by KIN28 might also enhance the ability of BUR1/BUR2 to phosphorylate Ser2, as shown previously for CTK1 (Jones et al., 2004). Our purified BUR1/BUR2 does not phosphorylate Ser5-phosphorylated or unphosphorylated CTD peptides of 4 heptad repeats under conditions where it phosphorylates a GST-CTD substrate with the native 26 repeats (data not shown). While this is an interesting observation for future study, it precluded our ability to determine if Ser5P enhances Ser2 phosphorylation by BUR1/BUR2 in vitro.

Most bur1 mutations confer 6-AU sensitivity and are synthetically lethal with spt5-194 and ctk1Δ, but bur1-CΔ is resistant to 6-AU and confers only a slight growth defect in the spt5-194 background (Keogh et al., 2003). This suggests that decreasing BUR1/BUR2 recruitment to the Ser5-phosphorylated CTD by the -CΔ mutation has a modest effect on elongation, which agrees with our finding that Ser2P levels are only moderately reduced in the bur1-CΔ mutant. However, bur1-CΔ is synthetically lethal with ctk1Δ, which can now be explained by proposing that the moderate decrease in Ser2P levels conferred by bur1-CΔ is intolerable in the absence of CTK1. The same explanation can be extended to the bur1-as mutant, which produces a moderate decrease in Ser2P levels in CTK1 cells and strongly impairs growth only in the ctk1Δ background.

Considering that BUR1 is essential, it may seem surprising that the bur1-as mutant has almost no growth defect at high concentrations of NM-PP1, even though much lower NM-PP1 concentrations eliminate bur1-as/BUR2 kinase activity in vitro. We presume that NM-PP1 does not completely inhibit the bur1-as product in vivo, and that low-level kinase activity is sufficient for viability. Supporting this idea, substitution of Thr-240 in the BUR1 activation loop nearly destroys BUR1 kinase activity in vitro (Keogh et al., 2003; Yao and Prelich, 2002), but has little effect on growth in otherwise WT cells (Yao and Prelich, 2002) and confers only slow growth in the ctk1Δ background (Keogh et al., 2003). On the other hand, point mutations in conserved residues of the BUR1 kinase domain that likewise abolish kinase activity in vitro are lethal, presumably because they completely eliminate kinase function in vivo.

Our conclusion that BUR1/BUR2 plays an important role in Ser2 phosphorylation of promoter-proximal Pol II provides new insights into the observation that BUR2 promotes H3-K36Me3 formation, especially near the 5′ ends of constitutively expressed genes (Chu et al., 2007). We made a similar observation for induced ARG1, finding that H3-K36Me3 occupancy is reduced by inactivation of the bur1-as product near the 5′ end of the gene (Fig. S8). Ser2 phosphorylation by CTK1 stimulates H3-K36 trimethylation by SET2 in downstream coding sequences (Kizer et al., 2005; Krogan et al., 2003b; Li et al., 2003; Xiao et al., 2003). Hence, our proposal that BUR1/BUR2 phosphorylates Ser2 on promoter-proximal Pol II molecules provides a possible explanation for the role of BUR2 in stimulating H3-K36Me3 formation near promoters (Fig. 7B). Considering that SET2 contains a CID that interacts preferentially with CTD peptides doubly phosphorylated on Ser2 and Ser5 (Kizer et al., 2005), BUR1/BUR2-mediated Ser2 phosphorylation of CTD repeats already phosphorylated on Ser5 should enhance SET2 function near the promoter. The effect of bur2Δ in reducing H3-K36Me3 formation was not limited to the 5′ ends of the PYK1 and FLO8 genes (Chu et al., 2007), which fits with our finding that bur2Δ reduces Ser2P levels throughout the ARG1 ORF, and only makes a proportionately greater contribution at the 5′end.

Our ChIP analysis suggests that the occupancies of myc-BUR1, myc-BUR2 and myc-CTK1 do not vary greatly across the ARG1 gene, with BUR1/BUR2 moderately exceeding CTK1 at the 5′ end owing to the BUR1 CID (cf. results in Figs. 1, 3, and 4). Thus, the fact that BUR1/BUR2 and CTK1 make roughly equal contributions to Ser2P formation at the 5′ end of ARG1 might be explained quite simply by proposing that BUR1/BUR2 and CTK1 have similar kinase activities, as well as similar occupancies, near the promoter. On the other hand, the much greater contribution of CTK1 to Ser2P at the 3′end of ARG1 seems to imply a change in kinase activity between the 5′ and 3′ ends of ARG1 for BUR1/BUR2, CTK1, or both. For example, CTK1 could become more active as elongation proceeds, perhaps owing to the stimulatory effect of BUR1/BUR2 on CTK1 function deduced from our experiments, or to some other modification of the CTD. There is evidence that transient accumulation of H2B-Ub impedes CTK1 recruitment during GAL1 induction (Wyce et al., 2007), leading us to consider whether this mechanism could have a role in reducing CTK1 activity near the ARG1 promoter. However, it was reported that H2B-Ub accumulates transiently across the GAL1 ORF, not only at the 5′end. And as noted above, CTK1 occupancy is not substantially lower at the 5′ versus 3′ end of ARG1 (Fig. 4F), at least after 30 min of induction when our ChIP measurements were made.

Alternatively, BUR1/BUR2 might become less functional as transcription proceeds downstream. It could be proposed that a reduction in Ser5P distal from the promoter would diminish BUR1/BUR2 activity towards the 3′ end. This may be unlikely, however, because Ser5P remains quite high at the 3′ end of ARG1 (Fig. S3). In fact, it is uncertain whether Ser5P levels, or only the reactivity of RPB1 to Ser5P-specific (H14) antibodies, declines as elongation proceeds (Phatnani et al., 2004). In addition, Ser2P formation by CTK1 is highly stimulated by Ser5P (Jones et al., 2004), so that loss of Ser5P would likewise reduce CTK1 function towards the 3′ end of the gene. Uncovering the mechanisms responsible for the greatly different contributions of BUR1/BUR2 and CTK1 to Ser2P formation between the 5′ and 3′ ends of ARG1 remains an important goal for future research.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and plasmids used are listed in Table S1 and Table S2, and their construction or sources are described in the Supplementary Information. ChIP experiments were conducted using primers and antibodies as described in the Supplementary Information. Western analysis of WCEs prepared by TCA precipitation, and coimmunoprecipitation assays on native WCEs were conducted as described in the Supplementary Information, as were CTD peptide binding assays using synthetic biotin-conjugated peptides purchased from AnaSpec and streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. Purification of GST fusions and BUR1-TAP proteins and yeast growth assays to test NMPP1 sensitivity also are described in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Buratowski for BUR1 plasmids and Chhabi Govind, Dan Ginsburg, Stephen Buratowski and Greg Prelich for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn SH, Kim M, Buratowski S. Phosphorylation of serine 2 within the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain couples transcription and 3′ end processing. Mol Cell. 2004;13:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop AC, Buzko O, Shokat KM. Magic bullets for protein kinases. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01928-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho EJ, Kobor MS, Kim M, Greenblatt J, Buratowski S. Opposing effects of Ctk1 kinase and Fcp1 phosphatase at Ser 2 of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3319–3329. doi: 10.1101/gad.935901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho EJ, Takagi T, Moore CR, Buratowski S. mRNA capping enzyme is recruited to the transcription complex by phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3319–3326. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Simic R, Warner MH, Arndt KM, Prelich G. Regulation of histone modification and cryptic transcription by the Bur1 and Paf1 complexes. Embo J. 2007;26:4646–4656. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govind CK, Zhang F, Qiu H, Hofmeyer K, Hinnebusch AG. Gcn5 promotes acetylation, eviction, and methylation of nucleosomes in transcribed coding regions. Mol Cell. 2007;25:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CK, Shuman S. Distinct roles for CTD Ser-2 and Ser-5 phosphorylation in the recruitment and allosteric activation of mammalian mRNA capping enzyme. Mol Cell. 1999;3:405–411. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JC, Phatnani HP, Haystead TA, MacDonald JA, Alam SM, Greenleaf AL. C-terminal repeat domain kinase I phosphorylates Ser2 and Ser5 of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain repeats. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24957–24964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402218200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh MC, Kurdistani SK, Morris SA, Ahn SH, Podolny V, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Chin K, Punna T, Thompson NJ, et al. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell. 2005;123:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh MC, Podolny V, Buratowski S. Bur1 kinase is required for efficient transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7005–7018. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.7005-7018.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizer KO, Phatnani HP, Shibata Y, Hall H, Greenleaf AL, Strahl BD. A novel domain in Set2 mediates RNA polymerase II interaction and couples histone H3 K36 methylation with transcript elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3305–3316. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3305-3316.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarnitsky P, Cho EJ, Buratowski S. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2452–2460. doi: 10.1101/gad.824700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Dover J, Wood A, Schneider J, Heidt J, Boateng MA, Dean K, Ryan OW, Golshani A, Johnston M, et al. The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation. Mol Cell. 2003a;11:721–729. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Kim M, Tong A, Golshani A, Cagney G, Canadien V, Richards DP, Beattie BK, Emili A, Boone C, et al. Methylation of histone H3 by Set2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is linked to transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2003b;23:4207–4218. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4207-4218.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laribee RN, Krogan NJ, Xiao T, Shibata Y, Hughes TR, Greenblatt JF, Strahl BD. BUR kinase selectively regulates H3 K4 trimethylation and H2B ubiquitylation through recruitment of the PAF elongation complex. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Greenleaf AL. A protein kinase that phosphorylates the C-terminal repeat domain of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3624–3628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Howe L, Anderson S, Yates JR, 3rd, Workman JL. The Set2 histone methyltransferase functions through the phosphorylated carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8897–8903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Moazed D, Gygi SP. Association of the histone methyltransferase Set2 with RNA polymerase II plays a role in transcription elongation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49383–49388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licatalosi DD, Geiger G, Minet M, Schroeder S, Cilli K, McNeil JB, Bentley DL. Functional interaction of yeast pre-mRNA 3′ end processing factors with RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom DL, Hartzog GA. Genetic interactions of Spt4-Spt5 and TFIIS with the RNA polymerase II CTD and CTD modifying enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2001;159:487–497. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.2.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall NF, Peng J, Xie Z, Price DH. Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27176–27183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhart A, Kamenski T, Hoeppner S, Baumli S, Cramer P. A structural perspective of CTD function. 2005;19:1401–1415. doi: 10.1101/gad.1318105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S, Udupa R, Yao S, Hartzog G, Prelich G. Phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain by the Bur1 cyclin-dependent kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4089–4096. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4089-4096.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, Dole S, Struhl K. The Rtf1 component of the Paf1 transcriptional elongation complex is required for ubiquitination of histone H2B. J Biol Chem. 2003a;278:33625–33628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, Robert F, Young RA, Struhl K. Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol Cell. 2003b;11:709–719. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patturajan M, Conrad NK, Bregman DB, Corden JL. Yeast carboxyl-terminal domain kinase I positively and negatively regulates RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27823–27828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlin BM, Price DH. Controlling the elongation phase of transcription with P-TEFb. Mol Cell. 2006;23:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phatnani HP, Greenleaf AL. Phosphorylation and functions of the RNA polymerase II CTD. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2922–2936. doi: 10.1101/gad.1477006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phatnani HP, Jones JC, Greenleaf AL. Expanding the functional repertoire of CTD kinase I and RNA polymerase II: novel phosphoCTD-associating proteins in the yeast proteome. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15702–15719. doi: 10.1021/bi048364h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Hu C, Wong CM, Hinnebusch AG. The Spt4p subunit of yeast DSIF stimulates association of the Paf1 complex with elongating RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3135–3148. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3135-3148.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder SC, Schwer B, Shuman S, Bentley D. Dynamic association of capping enzymes with transcribing RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2435–2440. doi: 10.1101/gad.836300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims RJ, 3rd, Belotserkovskaya R, Reinberg D. Elongation by RNA polymerase II: the short and long of it. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2437–2468. doi: 10.1101/gad.1235904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Qiu H, Hu C, Dong J, Hinnebusch AG. Yeast cap binding complex (CBC) impedes recruitment of cleavage factor IA to weak termination sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00733-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A, Schneider J, Dover J, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. The Paf1 complex is essential for histone monoubiquitination by the Rad6-Bre1 complex, which signals for histone methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34739–34742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A, Schneider J, Dover J, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. The Bur1/Bur2 complex is required for histone H2B monoubiquitination by Rad6/Bre1 and histone methylation by COMPASS. Mol Cell. 2005;20:589–599. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A, Shilatifard A. Bur1/Bur2 and the Ctk complex in yeast: the split personality of mammalian P-TEFb. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1066–1068. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.10.2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyce A, Xiao T, Whelan KA, Kosman C, Walter W, Eick D, Hughes TR, Krogan NJ, Strahl BD, Berger SL. H2B ubiquitylation acts as a barrier to Ctk1 nucleosomal recruitment prior to removal by Ubp8 within a SAGA-related complex. Mol Cell. 2007;27:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T, Hall H, Kizer KO, Shibata Y, Hall MC, Borchers CH, Strahl BD. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II CTD regulates H3 methylation in yeast. Genes Dev. 2003;17:654–663. doi: 10.1101/gad.1055503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T, Shibata Y, Rao B, Laribee RN, O'Rourke R, Buck MJ, Greenblatt JF, Krogan NJ, Lieb JD, Strahl BD. The RNA polymerase II kinase Ctk1 regulates positioning of a 5′ histone methylation boundary along genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:721–731. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01628-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao S, Neiman A, Prelich G. BUR1 and BUR2 encode a divergent cyclin-dependent kinase-cyclin complex important for transcription in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7080–7087. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7080-7087.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao S, Prelich G. Activation of the Bur1-Bur2 cyclin-dependent kinase complex by Cak1. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6750–6758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6750-6758.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.