Abstract

Recent studies have implicated the involvement of Ca2+-dependent mechanisms, in particular calcium/calmodulin-protein kinase II (CaM kinase II) in nicotine-induced antinociception using the tail-flick test. The spinal cord was suggested as a possible site of this involvement. The present study was undertaken to investigate the hypothesis that similar mechanisms exist for nicotine-induced antinociception in the hot-plate test, a response thought to be centrally mediated. In order to assess these mechanisms, i.c.v. administered CaM kinase II inhibitors were evaluated for their effects on antinociception produced by either i.c.v. or s.c. administration of nicotine in both tests. In addition, nicotine’s analgesic effects were tested in mice lacking half of their CaM kinase II (CaM kinase II heterozygous) and compare it to their wild-type counterparts. Our results showed that although structurally unrelated CaM kinase II inhibitors blocked nicotine’s effects in the tail-flick test in a dose-related manner, they failed to block the hot-plate responses. In addition, the antinociceptive effects of systemic nicotine in the tail-flick but not the hot-plate test were significantly reduced in CaM kinase II heterozygous mice. These observations indicate that in contrast to the tail-flick response, the mechanism of nicotine-induced antinociception in the hot-plate test is not mediated primarily via CaM kinase II-dependent mechanisms at the supraspinal level.

1. Introduction

Activation of cholinergic pathways by nicotine elicits antinociceptive effects in a variety of acute and chronic pain models [1–3]. There is strong evidence that the antinociceptive effect of nicotine can occur via activation of nAChRs expressed in a variety of brain loci and spinal cord [1, 2, 4–10]. Recent reports suggest that multiple nicotinic receptor subtypes are involved in the antinociceptive effects of nicotine. In addition, the identity of neuronal nAChRs subtypes engaged in nicotine’s analgesic effect seems to depend on the pain test used. Knockout mice deficient in the α4 and β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits lack nearly all high affinity 3H-nicotine and 3H-epibatidine binding sites and were insensitive to nicotine on the hot-plate test and display diminished sensitivity to nicotine in the tail-flick test [11]. These results suggest that supraspinal sites engaged in the hot-plate test are more likely to involve α4β2 neuronal subtypes as major component. In contrast, in the tail-flick assay, which involves a spinal reflex, both α4β2 and non-α4β2 nAChRs components of the nicotinic response are involved in mediating analgesia in the hot plate test. This difference in nAChRs subtypes involvement between the tail-flick and the hot-plate tests, may also suggest a differential activation of post-receptor signaling systems between the two pain modalities.

We recently, showed that nicotine increased [Ca2+]i levels in a concentration-dependent manner after application of the drug to spinal synaptosomes [12]. Furthermore, a dose-dependent increase in the spinal cord membrane calcium/dependent calmodulin protein kinase II (CaM kinase II) activity was seen after acute injection of nicotine in mice. In addition, CaM kinase II inhibitors blocked nicotine’s effects in the tail-flick test after systemic administration of the drug. Furthermore, we recently reported that nicotinic stimulation of β2-containing nAChRs in the spinal cord activates CaM kinase II and produce analgesia, which may require L-type calcium voltage-gated channels but not the intervention of glutamatergic transmission [13]. Collectively, these studies suggest that at least one mechanism of nicotinic receptor-mediated antinociception at the spinal level involves CaM kinase II, a calcium-dependent protein kinase. However, it is unknown if similar mechanisms occur in suprsapinal sites after nicotine exposure. For that, we investigated the effects of nicotine in the hot-plate test, an acute thermal pain test that involves supraspinal pain mechanisms.

The present study was undertaken to investigate the hypothesis that following acute exposure to nicotine, supraspinal and spinal mechanisms of nicotine-induced antinociception differentially involve CaM kinase II. For that, behavioral approaches and genetically modified mice were used. We first investigated the involvement of CaM kinase II in nicotine-induced antinociception using two different acute thermal pain tests. In these studies, CaM kinase II membrane-permeable inhibitors were tested for their effects on antinociception produced by either i.c.v. or s.c. administration of nicotine in the tail-flick and hot-plate tests. The s.c. route of administration was chosen because the hot-plate and tail-flick tests are mainly mediated by supraspinal and spinal mechanisms, respectively. We then confirmed our pharmacological observations by testing nicotine-induced antinociception using the two pain tests in mice lacking half of their CaM kinase II (CaM kinase II heterozygous) and compare it to their wild-type counterparts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male ICR mice (20–25g) obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) were used throughout the study. Male CaM kinase II heterozygous (heterozygotes for the Camk2atm1Sva targeted mutation) and wild-type mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were housed in groups of six and had free access to food and water. Animals were housed in an AALAC approved facility and the study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University.

2.2. Drugs

KN-62, KN-93, KN-92 and KN-04 were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). (−)-Nicotine ditartrate salt was obtained from Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc. (Milwaukee, WI). (2-(N-(4-Methoxybenzenesulfonyl))amino-N-(4-chlorocinnamyl)-N-methylbenzylamine, phosphate) (KN-92), 2-(N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-N-(4-methoxybenzenesulfonyl))amino-N-(4-chlorocinnamyl)-N-methylbenzylamine (KN-93), 1-[N,O-bis(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-N-methyl--tyrosyl]-4-phenylpiperazine (KN-62), and 1-[N,O-bis(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-N-methyl--tyrosyl]-4-phenylpiperazine derivative (KN-04) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). KN-62, KN-93, KN-92 and KN-04 were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (2.5%DMSO). Nicotine was dissolved in physiological saline (0.9% sodium chloride). All doses are expressed as the free base of the drug.

2.3. Intraventricular injections

Intraventricular injections were performed according to the method of Pedigo et al. [14]. Mice were lightly anesthetized with ether and an incision was made in the scalp such that the bregma was exposed. Injections were performed using a 26-gauge needle with a sleeve of PE 20 tubing to control the depth of the injection. An injection volume of 5 μl was administered at a site 2 mm rostral and 2 mm caudal to the bregma at a depth of 2 mm.

2.4. Antinociceptive tests

2.4.1. Tail-flick test

Antinociception was assessed by the tail-flick method of D’Amour and Smith [15]. Briefly, mice were lightly restrained while a radiant heat source was shone onto the upper portion of the tail. Latency to remove the tail from the heat source was recorded for each animal. A control response (2–4 sec) was determined for each mouse before treatment, and test latency was determined after drug administration. In order to minimize tissue damage, a maximum latency of 10 sec was imposed. Antinociceptive response was calculated as percent maximum possible effect (% MPE), where %MPE = [(test-control)/(10-control)] × 100.

2.4.2. Hot-plate Test

Mice were placed into a 10 cm wide glass cylinder on a hot plate (Thermojust Apparatus) maintained at 55.0° C. Two control latencies at least ten min apart were determined for each mouse. The normal latency (reaction time) was ten to fifteen seconds. Antinociceptive response was calculated as percent maximum possible effect (% MPE), where %MPE = [(test-control)/(40-control) × 100]. The reaction time was scored when the animal jumped or licked its paws.

Groups of eight to twelve animals were used for each dose and for each treatment. The mice were tested 5 min after either i.c.v. or s.c. injection of nicotine. Antagonism studies were carried out by pretreating the mice with either saline or CaM-Kinase II inhibitors 5 min before nicotine (20 μg/mouse for i.c.v. and 2.5 mg/kg for s.c. injections). The animals were tested 5 min after administration of the agonist. The antinociceptive effects of nicotine in both tests were evaluated in CaM-Kinase II heterozygous and wild-type mice after doses of 1 and 2.5 mg/kg. Mice were tested 5 min after nicotine injection.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of all analgesic studies was performed using either t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test post hoc test when appropriate. All differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. AD50 values with 95% CL for behavioral data were calculated by unweighted least-squares linear regression as described by Tallarida and Murray [16].

3. Results

3.1. Effects of CaM kinase II inhibitors on nicotine-induced antinociception in the tail-flick test after systemic and i.c.v. administrations

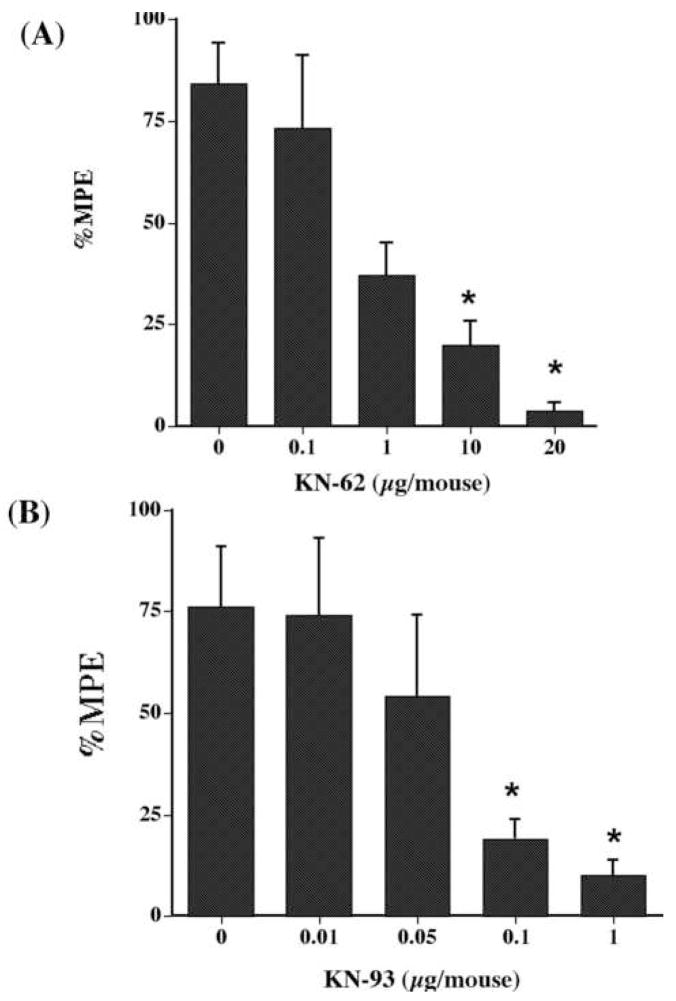

To investigate the involvement of CaM kinase II in nicotine’s effects in the tail-flick test after i.c.v. injection, two CaM kinase II inhibitors, KN-62 and KN-93, were evaluated for their ability to alter the antinociceptive effect of nicotine given either s.c. or i.c.v. KN-62 given i.c.v. inhibited the antinociceptive responses of centrally injected nicotine (20 μg/mouse) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). As illustrated, increasing doses of KN-62 produced a gradual inhibition of the antinociceptive response to 20 μg of nicotine, with an AD50 of 1 (0.09–1.7) μg/mouse. KN-62 alone did not significantly alter the tail-flick latencies produced following administration of any of the doses tested in this experiment. No external sign of toxicity was observed after i.c.v. injection of KN-62. On the other hand, KN-04 (20 μg/animal), an inactive structural analog of KN-62 that does not block CaM-kinase II, failed to significantly attenuate the antinociceptive effect of 20 μg/i.t. of nicotine (Nicotine group = 80 ± 12 %MPE versus KN-04 + Nicotine group = 79 ± 12 %MPE). Furthermore, KN-93, another CaM-kinase II inhibitor which is structurally unrelated to KN-62, given i.c.v. blocked nicotine-induced antinociception in a dose-related manner (Fig. 1B). The AD50 of KN-93 was 0.78 (0.18–0.95) μg/mouse. KN-93 alone did not significantly alter the tail-flick latencies produced following administration of any of the doses tested in this experiment. Pretreatment with KN-92 (1 μg/animal, i.t.), an inactive structural analog of KN-93 that does not block CaM-kinase II, did not significantly attenuated the antinociceptive effect of 20 μg/i.t of nicotine (Nicotine group = 83 ± 10 %MPE versus KN-92 + Nicotine group = 79 ± 14 %MPE).

Fig. 1.

Effects of (A) KN-62 and (B) KN-93 on the antinociceptive effect of nicotine after i.c.v. administration in the tail-flick test. Mice were pretreated i.c.v. with different doses of CaM kinase II inhibitors 5 min before nicotine (20 μg/animal, i.c.v.) and tested 5 min after the second injection in the tail-flick test. Each point represents the mean %MPE ± S.E. for 6–8 mice. *Statistically different from vehicle (dose 0) at P < 0.05.

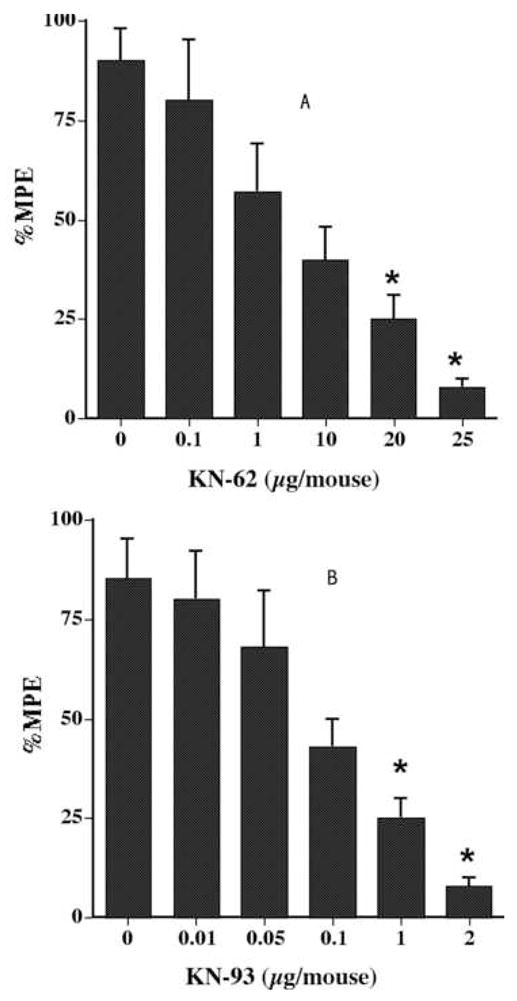

In another set of studies, mice were pretreated with CaM-kinase II inhibitors and then challenged with s.c. nicotine (2.5 mg/kg). Similar to what seen before, KN-62 and KN-93 given i.c.v., inhibited the antinociceptive responses of systemic injected nicotine (2.5 mg/kg) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A & 2B). As illustrated, increasing doses of KN-62 and KN-93 produced a dose-dependent inhibition of the antinociceptive response of nicotine, with an AD50 of 2.8 (1.9–7.5) and 0.37 (0.26–0.65) μg/mouse, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Effects of (A) KN-62 and (B) KN-93 on the antinociceptive effect of nicotine after s.c. administration in the tail-flick test. Mice were pretreated i.c.v. with different doses of CaM kinase II inhibitors 5 min before nicotine (2.5 mg/kg, s.c.) and tested 5 min after the second injection in the tail-flick test. Each point represents the mean %MPE ± S.E. for 6–8 mice. *Statistically different from vehicle (dose 0) at P < 0.05.

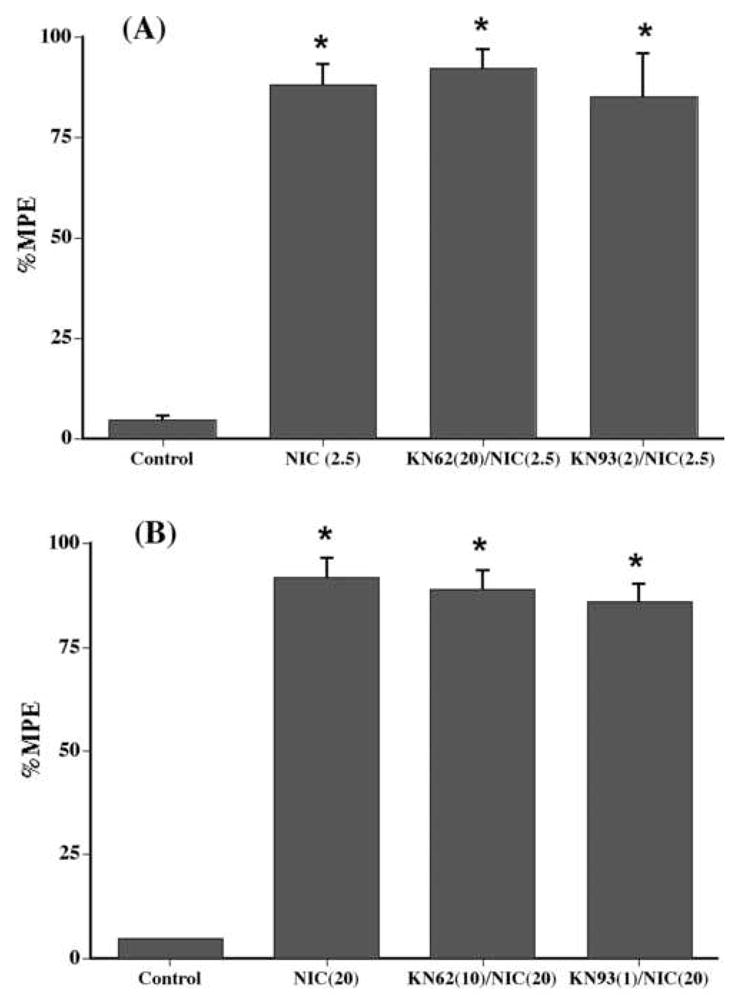

3.1. Effects of CaM kinase II inhibitors on nicotine-induced antinociception in the hot-plate test after i.c.v. administration

In contrast to the tail-flick test, i.c.v. KN-62 and KN-93 failed to inhibit the antinociceptive responses of centrally injected nicotine (20 μg/mouse) (Figure 3A) and systemic injected nicotine (2.5 mg/kg) (Figure 3B) in the hot-plate test. As illustrated, doses of KN-62 and KN-93 that produced a total inhibition of the antinociceptive response of nicotine in the tail-flick test did not significantly reduce nicotine’s effect in the hot-plate test. KN-62 and KN-93 by themselves did not significantly alter the tail-flick or hot-plate latencies produced following administration of any of the doses tested in this experiment (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Lack of effects of KN-62 and KN-93 on nicotine-induced antinociception after (A) s.c. and (B) i.c.v. administration of nicotine in the hot-plate test. Mice were pretreated i.c.v. with KN-62 (20 μg/animal) and KN-93 (20 μg/animal) 5 min before s.c. nicotine (2.5 mg/kg) or i.c.v. (20 μg/animal) and tested 5 min after the second injection in the hot-plate test. Each point represents the mean %MPE ± S.E. for 6–8 mice. *Statistically different from control at P < 0.05. NIC (2.5) = Nicotine at 2.5 mg/kg; NIC (20) = Nicotine at 20 μg/animal.

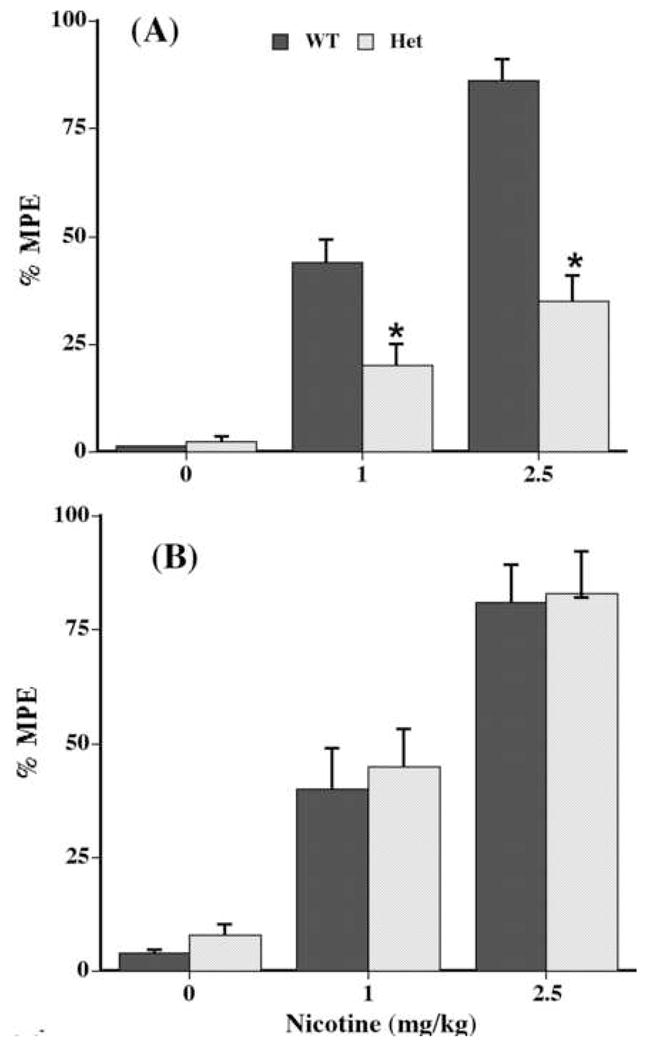

3.2. Nicotine-induced antinociception in CaM kinase II heterozygous and wild-type mice after systemic administration

We examined nicotine’s antinociceptive responses in CaM kinase II heterozygous and wild-type mice after s.c. administration. Antinociceptive effects of nicotine in the hot-plate and tail-flick tests are shown in Figure 4(A & B). The control latency response to painful stimuli did not significantly differ in wild-type and heterozygous animals in either test (data not shown). Using the tail-flick test, wild-type mice showed a dose-dependent antinociceptive response to nicotine (1 and 2.5 mg/kg). In addition, CaM kinase II heterozygous mice exhibit a significant decrease in the antinociceptive response to nicotine (Figure 4A). In contrast, no significant reduction of nicotine-induced antinociception was seen in the hot-plate test in CaM kinase II heterozygous mice (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

Antinociceptive effects of nicotine in CaM kinase II wild-type and heterozygous mice in (A) the tail-flick and (B) the hot-plate assays. Mice were treated s.c. nicotine (0, 1 and 2.5 mg/kg) and tested 5 min after in the two pain tests. Each point represents the mean %MPE ± S.E. for 6–8 mice. *Statistically different from control (dose 0) at P < 0.05. WT = wild-type CaM kinase II mice; Het = heterozygous CaM kinase II mice.

4. Discussion

Nicotinic agonists elicit antinociceptive responses in several acute pain tests, including tail-flick and hot-plate tests. Responses to the hot-plate are thought to be centrally mediated, whereas the tail-flick is considered a spinal reflex [17]. This study takes advantage of the opportunity to study a behavioral test by exploiting both specific targeted mutations in a candidate molecule and pharmacological antagonists for the same target. The studies reported here further tested the postulate that activation of calcium-mediated activation of CaM kinase II evokes the antinociceptive effects of nicotine on the hot-plate and tail-flick tests. Identification of the intracellular calcium-mediated signaling cascades activated after exposure to nicotine is important to our understanding of the mechanisms by which neuronal nAChRs mediate antinociceptive effects of the drug. Studies using nAChR subunit null mutant (gene knock-out) mice [11] and nicotinic antagonists [17], gain-of-function and inbred mouse strain [18] suggested that nicotine’s effects on the tail-flick and hot-plate tests involve at least partially separate pathways. We recently showed that activation of neuronal β2-containing nAChRs in the spinal cord leads to the influx of calcium, which can activate CaM kinase II resulting in an increase of the release of various neurotransmitters involved in pain inhibitory mechanisms [13]. Our results in the present study further expand and indicate that the supraspinal descendent and spinal mechanisms in the tail-flick antinociceptive effects of nicotine require the activation of CaM kinase II. This was also supported by that the fact that nicotine-induced antinociception in the tail-flick test was significantly reduced in CaM kinase II heterozygous mice.

Our recent studies using knock-out, gain-of-function and inbred mouse strain [11, 13] indicate that within the set of nAChR subtypes, activation of α4β2* nAChRs is both necessary and sufficient for nicotine-evoked antinociception in the hot-plate test. In addition, since β2-containing nAChRs in the spinal cord mediate the activation of CaM kinase II for nicotine’s effects in the tail-flick, our initial speculation was that similar calcium-mediated events occur also in nicotine-induced antinociception in the hot-plate test. Surprisingly, our results suggest that a calcium-dependent CaM kinase II molecular mechanism is not involved in this test. The lack of blockade of nicotine’s analgesic actions in the plate by selective CaM kinase II inhibitors (even at doses 10 to 20-times higher than AD50 values as determined in the tail-flick test) was complemented by the lack of significant reduction of the effect in the CaM kinase II heterozygous mice. These observations indicate that the mechanism of nicotine-induced antinociception in the hot-plate test is not mediated primarily via CaM kinase II-dependent mechanisms at the supraspinal level. However, other non-CaM kinase II factors downstream from α4β2-nAChR, influence responses to nicotine in this test. Indeed, the s.c. nicotine-induced antinociception arising from supraspinal sites appears to involve, at least, spinal muscarinic, serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms as measured in the hot-plate test [19].

Although compelling indications [11, 18] showed that among the set of nAChR receptor subtypes, α4β2* nAChRs play an important role in the tail-flick and hot-plate tests (with α4β2* nAChRs dominating nicotine’s actions on the hot-plate test), it likely that nicotine-evoked behavioral responses in the hot-plate assay depends on the activation of downstream events not directly related to CaMKII activation.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the technical assistance of Tie Han.

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants # DA-12610.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CaM kinase II

Calcium-dependent calmodulin protein Kinase II

- nAChR

Acetylcholine nicotinic receptor

- CNS

Central nervous system

- %MPE

maximum possible effect

- CL

confidence limit for the AD50

- s.c

subcutaneous injection

- i.c.v

intracerebroventricular injection

- AD50

antagonist dose 50%

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aceto MD, Bagley RS, Dewey WL, Fu TC, Martin BR. The spinal cord as a major site for the antinociceptive action of nicotine in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25(9):1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattila MJ, Ahtee L, Saarnivaara L. The analgesic and sedative effects of nicotine in white mice, rabbits and golden hamsters. Ann Med Exp Fenn. 1968;46:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phan DV, Doda M, Bite A, György L. Antinociceptive activity of nicotine. Acta Physiol Acad Scient Hungaricae. 1973;44(1):85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwamoto ET, Marion L. Adrenergic, serotonergic and cholinergic components of nicotinic antinociception in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265(2):777–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwamoto ET. Antinociception after nicotine administration into the mesopontine tegmentum of rats: evidence for muscarinic actions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251(21):412–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwamato ET. Characterization of the antinociception induced by nicotine in the pedunculus tegmental nucleus and the nucleus raphe magnus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;257:120–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott Bitner R, NA L, Curzon P, Arneric SP, Bannon AW, Decker MW. Role of the nucleus raphe magnus in antinociception produced by ABT-594: immediate early gene responses possibly linked to neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on serotonergic neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5426–5432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05426.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen M-K, Smith DF. Antinociceptive effects of the stereoisomers of nicotine given intrathecally in spinal rats. J Neural Transm. 1990;80:189–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01245120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damaj MI, Fei-Yin M, Dukat M, Glassco W, Glennon RA, Martin BR. Antinociceptive responses to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligands after systemic and intrathecal administration in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:1058–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan IM, Yaksh TL, Taylor P. Epibatidine binding sites and activity in the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1997;753:269–282. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marubio LM, A-JMM M, C-E M, L C, L N, dKdE A, H M, DM I, J-PC Reduced antinociception in mice lacking neuronal nicotinic receptor subunits. Nature. 1999;398:805–810. doi: 10.1038/19756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damaj MI. The involvement of spinal Ca2+/calmodulin-protein kinase II in nicotine-induced antinociception in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 404;103–110:2000. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damaj MI. Nicotinic regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activation in the spinal cord. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320(1):244–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedigo NW, Dewey WL, Harris LS. Determination and characterization of the antinociceptive activity of intraventricularly administered acetylcholine in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;193:845–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Amour FE, Smith DL. A method for determining loss of pain sensation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1941;72:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tallarida RJ, Murray RB. Manual of pharmacological calculations with computer programs. Springer-Verlag: New York; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caggiula AR, Epstien LH, Perkins KA, Saylor S. Different methods of assessing nicotine-induced antinociception may engage different neural mechanisms. Psychopharmaacology. 1995;122:301–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02246552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damaj I, Fonck C, Marks MJ, Deshpande PG, Labarca C, Lester HA, Collins AC, Martin BR. Genetic approaches identify differential roles for α4β2* nicotinic receptors in acute models of antinociception in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007 doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.112649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers D, Iwamoto E. Multiple spinal mediators in parenteral nicotine-induced antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267(1):341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]