Abstract

The penis is kept in the flaccid state mainly via a tonic activity of norepinephrine and endothelins (ETs). ET-1 is important in salt-sensitive forms of hypertension. We hypothesized that cavernosal responses to ET-1 are enhanced in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt mice and that blockade of ETA receptors prevents abnormal responses of the corpus cavernosum in DOCA-salt hypertension. Male C57BL/6 mice were unilaterally nephrectomized and treated for 5 weeks with both DOCA and water containing 1% NaCl and 0.2% KCl. Control mice were uninephrectomized and received tap water with no added salt. Animals received either the ETA antagonist atrasentan (5 mg·day−1·kg−1 body weight) or vehicle. DOCA-salt mice displayed increased systolic blood pressure (SBP), and treatment with atrasentan decreased SBP in DOCA-salt mice. Contractile responses in cavernosal strips from DOCA-salt mice were enhanced by ET-1, phenylephrine, and electrical field stimulation (EFS) of adrenergic nerves, whereas relaxations were not altered by IRL-1620 (an ETB agonist), acetylcholine, sodium nitroprusside, and EFS of nonadrenergic noncholinergic nerves. PD59089 (an ERK1/2 inhibitor), but not Y-27632 (a Rho-kinase inhibitor), abolished enhanced contractions to ET-1 in cavernosum from DOCA-salt mice. Treatment of DOCA-salt mice with atrasentan did not normalize cavernosal responses. In summary, DOCA-salt treatment in mice enhances cavernosal reactivity to contractile, but not to relaxant, stimuli, via ET-1/ETA receptor-independent mechanisms.

Keywords: endothelin-1, ETA receptor, Rho-kinase, DOCA-salt hypertension, corpus cavernosum, ERK1/2, atrasentan

Introduction

Whereas neurogenic nitric oxide (NO) is considered the most important mediator of penile erection, the penis is kept in the flaccid state mainly via a tonic activity of norepinephrine derived from the sympathetic nervous system and endothelins (Andersson 2001, 2003; Leite et al. 2007). Penile smooth muscle cells not only respond to, but also synthesize, endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Granchi et al. 2002). Both endothelial and smooth muscle cells of the human penis express ET-1, its converting enzyme (ECE-1), and the ET-1 receptors ETA and ETB. In addition, ET-1 expression in human fetal penile smooth muscle cells is increased by several stimuli, such as growth factors, cytokines, and hypoxia (Granchi et al. 2002). Both ETA and ETB receptors have been reported in the cavernosal tissue of different animal species (Saenz de Tejada et al. 1991; Holmquist et al. 1992; Bell et al. 1995; Parkkisenniemi and Klinge 1996; Ari et al. 1996; Sullivan et al. 1997; Khan et al. 1999; Dai et al. 2000), and ET-1 injection into the penile vasculature induces both vasoconstriction and vasodilation (Ari et al. 1996). ET-1-induced cavernous vasoconstriction in vivo appears to be predominantly mediated by the ETA receptor, because ETA, but not ETB, receptor antagonists prevent ET-1-induced reduction of intracavernosal pressure, both in basal conditions and upon submaximal ganglionic stimulation (Dai et al. 2000). In the penis, ET-1/ETA receptor-mediated biological effects involve activation of the inositol trisphosphate (IP3)/calcium (Ca2+) and RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling pathways (Mills et al. 2001; Wingard et al. 2003), whereas ET-1/ETB receptor-mediated vasodilation occurs via release of NO from cavernous endothelial cells (Ari et al. 1996).

ET-1 is important in salt-sensitive forms of experimental hypertension, such as mineralocorticoid hypertension (Schiffrin 2005; Tostes and Muscara 2005). Salt-sensitive hypertensive animals display increased tissue ET-1 expression and abnormal vascular responses to ET-1; however, treatment of these animals with both selective ETA or dual ETA/ETB receptor antagonists results in regression of vascular damage, hypertrophy, and endothelial dysfunction (Schiffrin 2005). Therefore, we hypothesized that cavernosal contractile responses to ET-1 are enhanced in mice treated with deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt and that blockade of ETA receptors during the DOCA-salt treatment prevents abnormal responses of the corpus cavernosum in this salt-sensitive model of hypertension. To test our hypothesis, we evaluated changes in corpora cavernosa reactivity to ET-1 and IRL-1620, an ETB agonist, as well as responses to other contractile and relaxant stimuli. In addition, the effect of chronic treatment with an ETA receptor antagonist (atrasentan) on cavernosal reactivity was determined.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (12 weeks old, 25–30 g) (Harlan, Indianapolis, Ind.) were used in these studies. All procedures were performed in accordance with the APS Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals, approved by the Medical College of Georgia Committee on the Use of Animals in Research and Education. The animals were housed 4 per cage on a 12 h light : 12 h dark cycle and fed a standard chow diet with water ad libitum.

DOCA-salt hypertension and arterial blood pressure measurements

DOCA-salt hypertension was induced as previously described (Chitaley et al. 2001). Briefly, mice were unilaterally nephrectomized and 1 g·kg−1 DOCA silastic pellets were implanted subcutaneously at the scapular region. DOCA mice received water containing 1% NaCl and 0.2% KCl for 5 weeks. Control mice were also uninephrectomized and received tap water with no salt added. Animals simultaneously received either the ETA antagonist atrasentan (5 mg·day−1·kg−1 of body weight) in the drinking water or vehicle. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured in un-anaesthetized animals by tail cuff using a RTBP1001 mouse-tail blood pressure system (Kent Scientific Corporation, Conn.). At the end of 5 weeks of treatment, mice were submitted to the experimental procedures described below.

Drugs and solutions

Physiological salt solution of the following composition was used: 130 mmol/L NaCl, 14.9 mmol/L NaHCO3, 5.5 mmol/L dextrose, 4.7 mmol/L KCl, 1.18 mmol/L KH2PO4, 1.17 mmol/L MgSO4·7H2O, 1.6 mmol/L CaCl2·2H2O, and 0.026 mmol/L EDTA. Acetylcholine, atropine, Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), phenylephrine, PD59089, sodium nitroprusside, and bretylium tosylate ((o-bromobenzyl) ethyldimethylammonium p-toluenesulfonate) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). ET-1, IRL-1620 (succinyl-[Glu9,Ala11,15]-endothelin-1(8–21)), and Y-27632 were from Tocris (Ellisville, Mo.). Atrasentan was kindly provided by Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, Ill.). All reagents used were of analytical grade. Stock solutions were prepared in deionized water and stored in aliquots at −20 °C; dilutions were made up immediately before use.

Functional studies in cavernosal strips

After euthanasia, penes were excised, transferred into ice-cold buffer, and dissected to remove the tunica albuginea, as previously described (Tostes et al. 2007). One crural strip preparation (1 × 1 × 10 mm) was obtained from each corpus cavernosum (2 crural strips from each penis). Cavernosal strips were mounted in 4-millilitre myograph chambers (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) containing buffer at 37 °C continuously bubbled with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The tissues were stretched to a resting force of 2.5 mN and allowed to equilibrate for 60 min. Changes in isometric force were recorded with a PowerLab/8SP data acquisition system (Chart software, version 5.0; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, Colo.). To verify the contractile ability of the preparations, a high potassium chloride (KCl) solution (120 mmol/L) was added to the organ baths at the end of the equilibration period. Cumulative concentration–response experiments with acetylcholine (10−9 mol/L to 3 × 10−6 mol/L) (an endothelium-dependent vasodilator), sodium nitroprusside (10−9 mol/L to 3 × 10−5 mol/L) (a nitric oxide donor and endothelium-independent vasodilator), and IRL-1620 (10−9 mol/L to 10−6 mol/L) (a selective ETB agonist) were performed in cavernosal strips contracted with phenylephrine (PE) (10−5 mol/L). Concentration–response experiments with Y-27632 (3 × 10−8 mol/L to 3 × 10−5mol/L) (a Rho-kinase inhibitor) were performed in cavernosal strips contracted with ET-1 (10−6 mol/L). Cumulative concentration–response experiments with ET-1 (10−9 mol/L to 3 × 10−6 mol/L), IRL-1620 (10−10 mol/L to 10−6 mol/L) (a selective ETB agonist), and PE (10−9 mol/L to 10−4 mol/L) (an α1-adrenergic receptor agonist) were also performed with strips under basal tone. Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was applied to cavernosal strips placed between platinum pin electrodes attached to a stimulus splitter unit (Stimu-Splitter II), which was connected to a Grass S88 stimulator (Astro-Med West Warwick, R.I.). EFS was conducted at 20 V, 1 ms pulse width and trains of stimuli lasting 10 s at varying frequencies (1 to 64 Hz). To evaluate adrenergic nerve-mediated responses, strips were incubated with l-NAME (10−4 mol/L) plus atropine (10−6 mol/L) before EFS was performed. To determine relaxant responses to non-adrenergic noncholinergic (NANC) nerve stimulation, strips were treated with bretylium tosylate (3 × 10−5 mol/L) and atropine (10−6 mol/L) for 45 min, contracted with PE (10−5 mol/L), and then EFS was performed. When antagonists or inhibitors were used, drugs were introduced 30–45 min before concentration–response or frequency–response experiments were performed. Time control experiments were performed to determine force development of cavernosal strips not related to the effects of each antagonist/inhibitor. Control solutions containing vehicle levels of ethanol and DMSO were also used throughout the experimental protocols.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from cavernosal strips by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen Sciences, Md.). The quantity, purity, and integrity of all RNA samples were determined by the NanoDrop spectrophotometers (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, Del.). One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed in a final volume of 50 µL using the high-capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), and single-strand cDNA was stored at −20 °C. Primers for preproET-1 mRNA were obtained from Applied Biosystems (No. Mn00438656_m1). Real-time reverse transcription – polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) reactions were performed using the 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) in a total volume of 20 µL reaction mixture following the manufacturer’s protocol, using the TaqMan Fast Universal PCR master mix (2X) (Applied Bio-systems) and 0.1 µmol/L of each primer. Negative controls contained water instead of first-strand cDNA. Each sample was normalized on the basis of its 18S ribosomal RNA content. The 18S quantification was performed using a TaqMan ribosomal RNA reagent kit (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Relative gene expression for preproET-1 mRNA was normalized to a calibrator that was chosen to be the basal condition (untreated sample) for each time point. Results were calculated with the ΔΔCt method and expressed as n-fold differences in preproET-1 gene expression relative to 18S rRNA and to the calibrator and were determined as follows: n-fold = 2−(ΔCt sample – ΔCt calibrator), where the parameter Ct (threshold cycle) is defined as the fractional cycle number at which the PCR reaction reporter signal passes a fixed threshold. ΔCt values of the sample and the calibrator were determined by subtracting the average Ct value of the transcript under investigation from the average Ct value of the 18S rRNA gene for each sample.

Statistical analysis

Contractions were recorded as changes in the displacement from baseline and were presented as millinewtons (mN) for n experiments. Relaxation was expressed as percentage change from the PE- or ET-1-contracted levels. Agonist concentration–response curves were fitted by using a nonlinear interactive fitting program (Graph Pad Prism 4.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, Calif.). Agonist potencies and maximum responses were expressed as pD2 (negative logarithm of the ED50, the molar concentration of agonist producing 50% of the maximum response) and Emax (maximum effect elicited by the agonist), respectively. Constraining curve-fit parameters were used to fit a sigmoidal curve and to determine pD2 values for IRL-1620, Y-27632, and sodium nitroprusside. Statistically significant differences were calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t test. p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

At 5 weeks of treatment, DOCA-salt mice compared with their control (Uni) littermates displayed increased SBP but no differences in body weight between groups (Table 1). Treatment with the ETA antagonist atrasentan decreased SBP in DOCA-salt animals. Treatment with the ETA antagonist did not change body weight in control or DOCA-salt mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Systolic blood pressure, body weight, and cavernosal weight of control and DOCA-salt hypertensive mice after 5 weeks of treatment with the ETA antagonist atrasentan.

| Uni | DOCA-salt | Uni + atrasentan | DOCA-salt + atrasentan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP, mmHg (n = 12–15) | 103±3 | 131±4* | 97±2 | 108±3*,† |

| Body weight, g (n = 12–15) | 27.2±0.7 | 28.3±1.1 | 27.0±0.8 | 29.3±0.6 |

| Cavernosal strip weight, g | 1.97±0.09 | 1.98±0.07 | 1.97±0.14 | 1.94±0.11 |

Note:Uni, uninephrectomized control littermates; SBP, systolic blood pressure. Values are means ± SE, n = 12–15 each group.

Significant at, p < 0.05 vs. respective control.

p < 0.05 vs. nontreated (vehicle) DOCA-salt.

Effects of DOCA-salt hypertension and ETA antagonist treatment on cavernosal reactivity

Stimulation with 120 mmol/L KCl induced a contractile response of 0.83 ± 0.13 mN in cavernosal strips from control mice (n = 14) and 0.88 ± 0.09 mN in DOCA-salt mice (n = 14). Treatment with atrasentan did not change contractile responses to KCl in tissues from control (0.76 ± 0.09 mN) (n = 10) or DOCA-salt (0.90 ± 0.13 mN) (n = 14) mice.

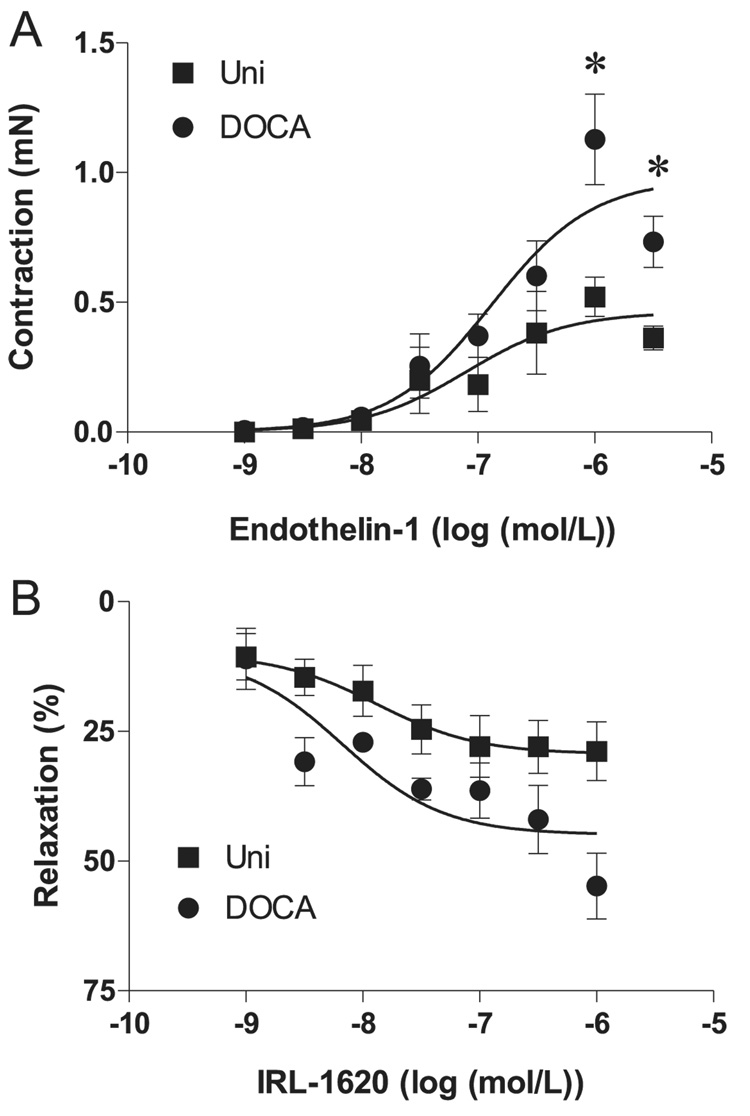

In the first set of experiments, we evaluated responses induced by ET-1 and IRL-1620, an ETB receptor agonist. Contractile responses to ET-1, which were nearly abolished by the addition of ETA antagonist in the bath in all groups (not shown), were enhanced in strips from DOCA-salt mice (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). Considering that activation of smooth muscle cell ETB receptors induces contraction, whereas endothelial cell ETB receptors stimulate the release of NO and prostacyclin and, consequently, induce vasodilation, responses to the ETB agonist IRL-1620 were tested both under basal tone and after cavernosal strips were stimulated with PE (10−5 mol/L). IRL-1620 did not induce contractile responses when tested in tissues at basal tone, either in the absence or presence of 10−4 mol/L l-NAME, but produced relaxation of cavernosal strips contracted with 10−5 mol/L PE (Fig. 1B). Although a tendency to increased relaxation to IRL-1620 was observed in cavernosal strips from DOCA-salt mice, the relaxant responses to the ETB agonist were similar in tissues from control and DOCA-salt animals.

Fig. 1.

Response of cavernosal strips from Uni control (■) and DOCA-salt (●) mice to ET-1 (A), and the ETB agonist IRL-1620 (B). Relaxation induced by IRL-1620 was calculated relative to the maximal changes from the contraction produced by phenylephrine in each tissue, which was taken as 100%. Data are means ± SE, n = 5–7 each group. Significant at *, p < 0.05 vs. Uni mice.

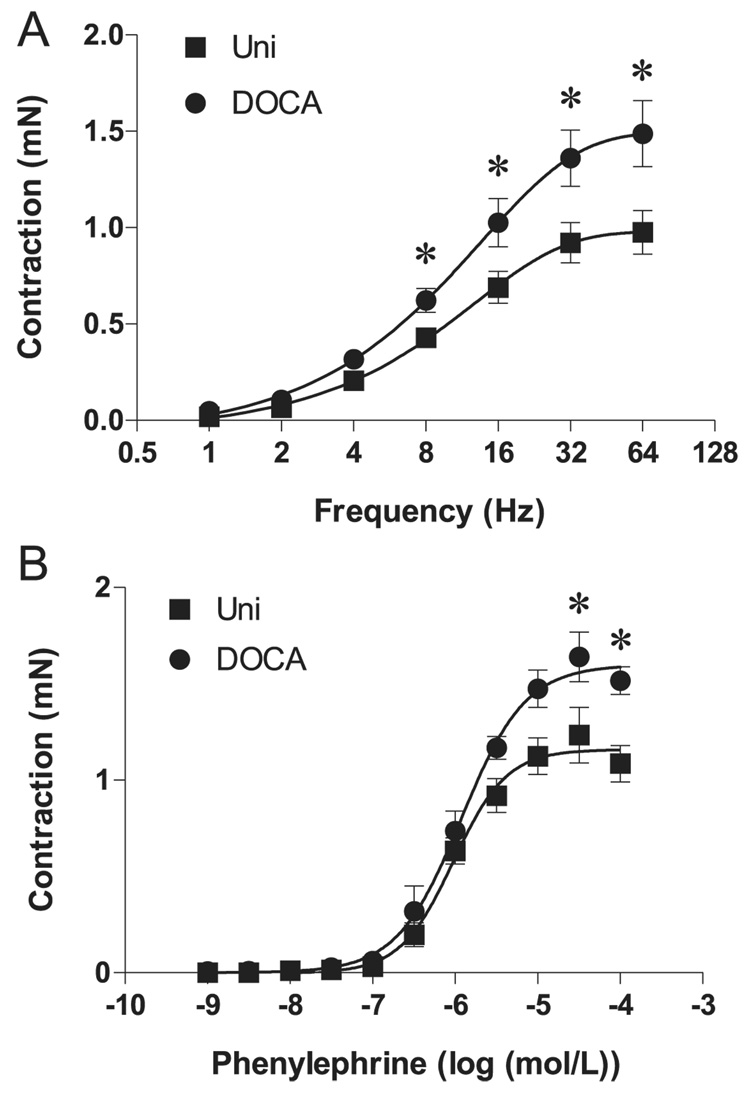

Changes in cavernosal reactivity to other contractile and relaxant stimuli were also determined. After 45 min of incubation with 10−6 mol/L atropine (a muscarinic receptor antagonist) plus 10−4 mol/L L-NAME (a nonselective inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase) to avoid responses due to the stimulation of cholinergic and NANC nerves, EFS (1–64 Hz) produced frequency-dependent contractions in cavernosal smooth muscle strips (Fig. 2A). EFS-dependent contractions were virtually abolished by the sympathetic nerve-blocking agent bretylium tosylate (3 × 10−5 mol/L) and by the α-adrenergic antagonist terazosin (10−6 mol/L), confirming that these responses are neuronal in origin and adrenergic in nature (data not shown). Contractile responses induced by EFS of adrenergic nerves were enhanced in cavernosal strips from DOCA-salt mice, but not in control tissues (Fig. 2A). Similarly, contractile responses to the α-adrenergic receptor agonist phenylephrine were enhanced in cavernosal tissues from DOCA-salt mice (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Contractile response to stimulation of adrenergic nerves or α1-adrenergic receptors in cavernosal strips from Uni control (■) and DOCA-salt (●) mice. (A) Frequency–response curves elicited by electrical field stimulation (1–64 Hz) performed in the presence of 10−4 mol/L l-NAME plus 10−6 mol/L atropine (n = 14 each group). (B) Phenylephrine concentration–response curves in the absence of l-NAME (n = 7 each group). Data are means ± SE. Significant at *, p < 0.05 vs. Uni mice.

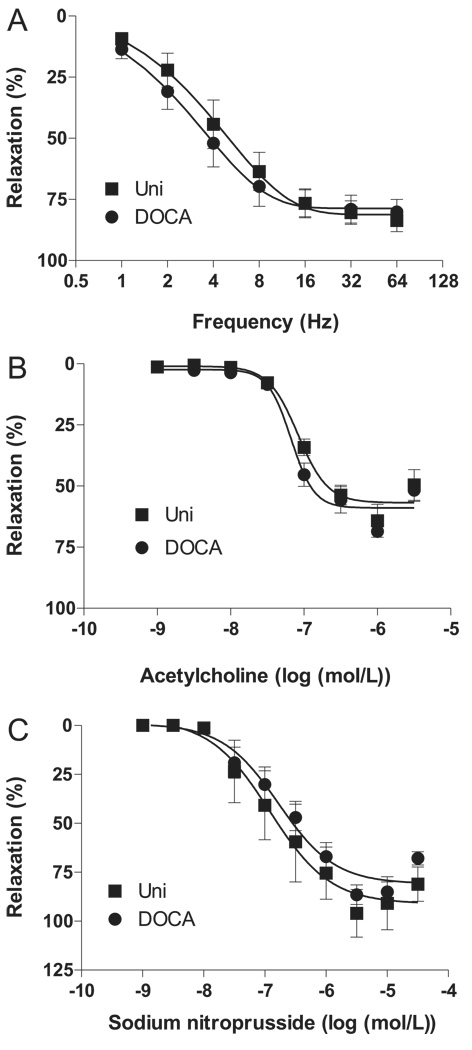

EFS (1–64 Hz) (n = 6) (Fig. 3A), as well as the cumulative addition of acetylcholine (10−9 to 3 × 10−6 mol/L) (n = 5) (Fig. 3B) or sodium nitroprusside (10−9 to 3 × 10−5 mol/L) (n = 6) (Fig. 3C), produced relaxation of PE-contracted cavernosal strips (p < 0.05). Relaxation responses to EFS, acetylcholine, and sodium nitroprusside were not altered in cavernosal tissues from DOCA-salt mice, in contrast to those in control tissues.

Fig. 3.

Relaxant response in cavernosal strips from Uni control (■) and DOCA-salt (●) mice. (A) Frequency–response curves elicited by electrical field (1–64 Hz) stimulation of NANC nerves in the presence of 3 × 10−5 mol/L bretylium tosylate plus 10−6 mol/L atropine (n = 7 each group). Relaxation induced by (B) acetylcholine (n = 12 each group) and (C) sodium nitroprusside (n = 4–5 each group) was calculated relative to the maximal changes from the contraction produced by phenylephrine in each tissue, which was taken as 100%. Data are means ± SE. NANC, nonadrenergic noncholinergic.

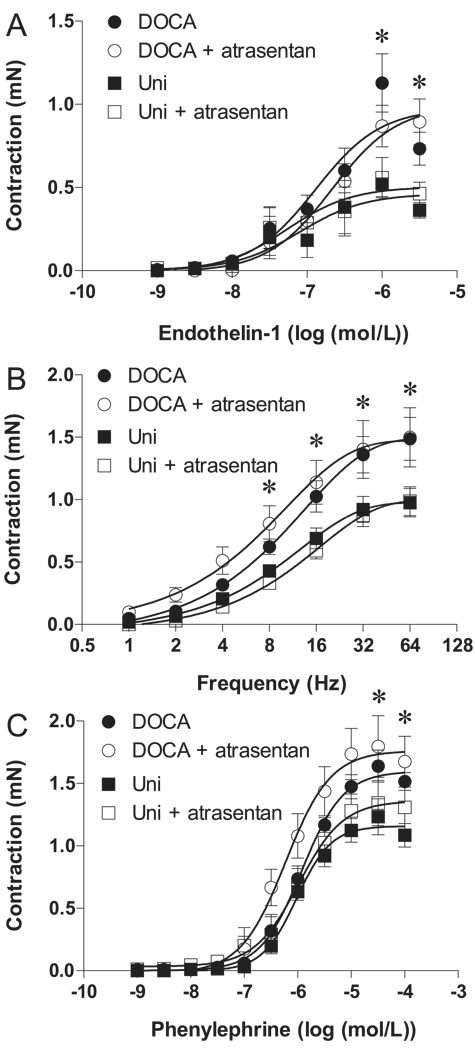

Treatment of animals with atrasentan did not modify contractile responses to ET-1 (Fig. 4A), EFS (Fig. 4B), or phenylephrine (Fig. 4C) in tissues from control and DOCA-salt mice (p < 0.05), and, at this condition, cavernosal strips from DOCA-salt mice still displayed enhanced contractile responses to these stimuli.

Fig. 4.

Effect of chronic treatment with the ETA antagonist atrasentan (open symbols) or vehicle (closed symbols) on contractile response of cavernosal strips from Uni control (■, □) and DOCA-salt (●, ○) mice. (A) ET-1 concentration–response curves in the absence of l-NAME (n = 5–7 each group). (B) Frequency–response curves elicited by electrical field (1–64 Hz) stimulation of adrenergic nerves in the presence of 10−4 mol/L l-NAME plus 10−6 mol/L atropine (n = 10–12 each group). (C) phenylephrine (α1-adrenergic receptor agonist) concentration–response curves in the absence of l-NAME (n = 5–7 each group). Data are means ± SE. Significant at *, p < 0.05 vs. Uni mice.

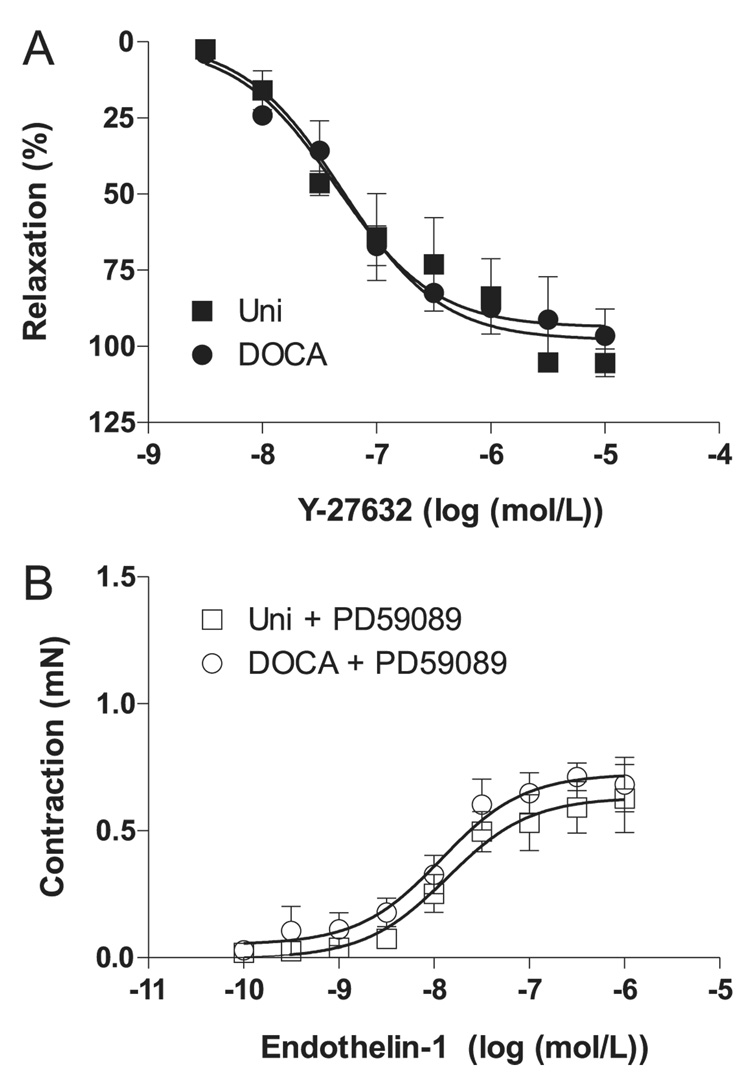

In the second set of experiments we aimed to determine the mechanisms involved in the increased ET-1 contractions in corpora cavernosa from DOCA-salt mice. Considering that ET-1 stimulates the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway in the penis (Mills et al. 2001; Wingard et al. 2003) and that DOCA-salt rats display decreased changes in intracavernosal pressure in response to Y-27632, a Rho-kinase inhibitor (Chitaley et al. 2001), we tested the effects of Y-27632 in isolated cavernosal strips from control and DOCA-salt mice. The Rho-kinase inhibitor Y-27632 induced relaxation of cavernosal strips contracted with ET-1, and relaxation responses were similar in tissues from DOCA-salt hypertensive and normotensive mice (Fig. 5A). Because ET-1 also activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway and p44/42 isoforms of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) are involved in the contractile responses mediated by ET-1 (Kawanabe et al. 2004; Beg et al. 2006), we evaluated the responses to ET-1 after incubation with an ERK1/2 inhibitor, PD59089 (10−6 mol/L). In this condition, no differences in ET-1-induced contractions were observed between cavernosal tissues from control and DOCA-salt mice, the inhibitor producing a greater attenuation of ET-1 responses in the DOCA-salt group (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effect on ET-1-contracted tissue in cavernosal strips from Uni control (■,□) and DOCA-salt (●,○) mice of (A) Y-27632, a Rhokinase inhibitor (n = 5 each group), and (B) PD59089, an ERK1/2 inhibitor (n = 6 each group). Relaxation induced by Y-27632 was calculated relative to the maximal changes from the contraction produced by ET-1 in each tissue, which was taken as 100%. Data are means ± SE.

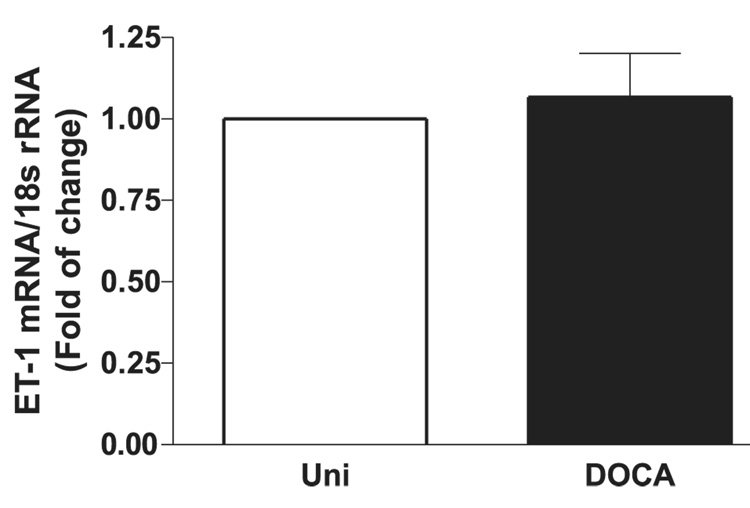

Expression levels of preproET-1 mRNA on cavernosal tissue

PreproET-1 mRNA levels in cavernosal tissues were compared between control and DOCA-salt animals with qPCR. PreproET-1 was not significantly increased in cavernosal tissue from DOCA-salt animals (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

PreproET-1 mRNA expression, determined by real-time qPCR, of 1 µg total RNA extracted from cavernosal tissue of Uni control (open bar) and DOCA-salt (filled bar) mice. Graph shows fold change in preproET-1 mRNA expression. Values were normalized by the corresponding 18s rRNA of each sample. Results are means ± SE (n = 5–6 each sample).

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that DOCA-salt treatment in mice is associated with a mild increase in blood pressure and increased cavernosal contractile responses to ET-1, the α-adrenergic receptor agonist phenylephrine, and EFS of adrenergic nerves. No changes in cavernosal relaxation induced by the ETB agonist IRL-1620, acetylcholine, or EFS of NANC nerves were observed. In addition, treatment of DOCA-salt mice with an ETA receptor antagonist, atrasentan, did not modify increased contractile responses in cavernosum from DOCA-salt mice.

In rats, DOCA-salt treatment for 5 weeks severely increases blood pressure and decreases erectile function (Chitaley et al. 2001). Although receiving a dose of deoxy-corticosterone 5 times greater (1 g/kg) than that normally used to treat rats (200 mg/kg), DOCA-salt mice displayed only a mild increase in blood pressure, in agreement with data from other groups (Peng et al. 2001; Hartner et al. 2003). Differences in response to DOCA-salt treatment depend on the murine genetic background. By using 4 mouse strains (129/Sv, C57BL/6, and F1 and F2 intercrosses of 129/Sv × C57BL/6), Hartner and colleagues (2003) showed that 129/Sv mice are more susceptible to the development of DOCA-induced high blood pressure and renal damage than C57BL/6 mice (Hartner et al. 2003). In addition, in 129Sv/Ev mice, the renal kallikrein–kinin system, which is activated under conditions of mineralocorticoid excess, exerts a protective role against the development of mineralocorticoid-induced hypertension (Emanueli et al. 1998). Whether the protective role of endogenous kinins is greater in C57BL/6 mice than in 129Sv/Ev or rats has not been investigated.

Although blood pressure was only mildly increased, abnormal contractile responses to ET-1, sympathetic nerve stimulation, and α1-adrenergic receptor activation were observed in isolated corpora cavernosa from DOCA-salt mice, indicating that changes in cavernosal reactivity, which may lead to erectile dysfunction or altered in vivo erectile function, are not driven exclusively by hypertension and (or) high blood pressure. In this sense, it has been extensively demonstrated that vasoactive peptides, such as angiotensin II and ET-1, exert deleterious effects in the vasculature that are blood pressure-independent (Schiffrin 2005; Savoia and Schiffrin 2007).

ET-1, which potently induces slowly developing, long-lasting contractions in the corporal smooth muscle cells and penile vessels, has been suggested to contribute to the maintenance of corpus cavernosal smooth muscle tone in other species (Ari et al. 1996; Mills et al. 2001; Andersson 2003; Wingard et al. 2003). Accordingly, a high prevalence of erectile dysfunction (ED) is observed among hypertensive men (Lewis 2004; Muller and Mulhall 2006), and ET-1 is considered one of the best independent predictors for ED (Bocchio et al. 2004). In addition, greater plasma levels of ET-1 were reported in the venous blood of patients with organic and psychogenic ED, but not in that of non-ED controls (Hamed et al. 2003; El Melegy et al. 2005). Furthermore, because ET-1 increases contractile responses to other vasoactive agents, one may speculate that increased contractions to EFS and phenylephrine are due to ET-1 effects. In penes from rats and humans, ET-1 increases contractile responses to phenylephrine (Wingard et al. 2003; Christ et al. 1995). In the rat penis, this synergistic effect is mediated via ETA receptors and involves activation of the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway (Wingard et al. 2003). Furthermore, the synergism between ET-1 and PE is associated with increased expression of RhoA in the membrane fraction of penis homogenates, and the Rho-kinase inhibitor Y-27632 relaxes the contraction induced by ET-1, PE, or its combination (Wingard et al. 2003). Our data showing that ETA receptor blockade does not change increased responses to EFS or phenylephrine, as well as the presence of similar relaxant responses to the Rho-kinase inhibitor between cavernosal strips from control and DOCA-salt mice, indicate that this may not be the case in mice.

The observation that treatment with atrasentan decreases blood pressure in DOCA-salt mice, but is not able to prevent changes in cavernosal reactivity, was surprising. Considering that in rats, ET-1/ETA receptors play a major role in altered vascular responses in DOCA-salt hypertension (Callera et al. 2003; Schiffrin 2005), it is possible that, in mice, the endothelin system is not the main factor driving the changes in cavernosal reactivity upon DOCA-salt treatment. Another possibility is that the cavernosal tissue displays a differential sensitivity to the effects of ET-1 or ETA receptor blockade, in contrast to that of other vascular beds. As an example, differential regulation of ET-1 contractile mechanisms has been demonstrated between murine mesenteric arteries and veins (Pérez-Rivera et al. 2005). Another possible explanation is that the cavernosal ET-1 system in mice is less susceptible to the effects of mineralocorticoid hypertension. Accordingly, no differences in preproET-1 mRNA expression were found on cavernosal tissue from DOCA-salt and control animals.

Considering that ET-1 increases Rho-kinase activity in the cavernous circulation (Mills et al. 2001), we determined whether increased responses to ET-1 in cavernosal strips of DOCA-salt mice were due to increased activation of the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway. The Rho-kinase inhibitor Y-27632 induced similar relaxation in cavernosal strips from control and DOCA-salt mice, indicating that increased ET-1 contractions are not due to increased Rho-kinase activity. Interestingly, in rats, intracavernosal injection of a selective Rho-kinase inhibitor augments ICP/MAP, but this effect is significantly suppressed in DOCA-salt rats, indicating increased Rho-kinase activity in penes from mineralocorticoid hypertensive rats. Because ET-1 also activates the MAPK signaling pathway and because the p44/42 isoforms of ERK1/2 are involved in the contractile responses mediated by ET-1 (Kawanabe et al. 2004; Beg et al. 2006), we evaluated the responses to ET-1 after incubation with an ERK1/2 inhibitor. The ERK1/2 inhibitor abolished increased contractile responses to ET-1 in cavernosum from DOCA-salt mice, indicating that increased contraction to ET-1 in cavernosum from DOCA-salt mice is mediated by increased ERK1/2 activity.

Although ERK1/2 are well known to mediate cellular responses initiated by growth factors (Aoki et al. 2000), recently it has been suggested that they play a role in vascular reactivity. In vivo studies have shown that ERK1/2 inhibition attenuates cerebral blood flow reduction and vasoconstriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats and also prevents the upregulation of vascular endothelin ETB receptors (Beg et al. 2006). In addition, ERK1/2 are involved in the upregulation of endothelin ETA and ETB receptors in porcine coronary arteries (Nilsson et al. 2008) and ETB receptors in rat cerebral arteries (Henriksson et al. 2004). Furthermore, Sommer and collaborators (2002) have demonstrated that patients with erectile dysfunction exhibited more active ERK1/2 in the cavernosal smooth muscle than did patients with normal erectile function. Taken together, these results suggest that ERK1/2 play a role in erectile dysfunction and that ET-1 may be a factor in triggering its activation, especially in salt-sensitive forms of experimental hypertension such as mineralocorticoid hypertension.

In summary, our study shows that after 5 weeks of treatment DOCA-salt mice exhibit altered cavernosal reactivity to ET-1 and to sympathetic nerve stimulation and α1-adrenergic receptor activation, which is not prevented by ETA-receptor blockade. Increased contractile responses to ET-1, which are mediated by ERK1/2 activation, may enhance corpus cavernosal smooth muscle tone and contribute to erectile dysfunction in DOCA-salt hypertensive animals.

Résumé

Le pénis est maintenu dans un état flasque principalement par un activité tonique de la norépinéphrine et des endothélines. L’ET-1 joue un rôle important dans les formes d’hypertension sensibles au sel. Nous avons émis l’hypothèse que les réponses du corps caverneux à l’ET-1 sont stimulées chez les souris DOCA (acétate de désoxycorticostérone) -sel, et que le blocage des récepteurs ETA prévient les réponses anormales du corps caverneux dans l’hypertension DOCA-sel. Des souris mâles ont été uninéphrectomisées et traitées avec du DOCA plus de l’eau contenant 1 % de NaCl et 0,2 % de KCl, pendant 5 semaines. Les souris témoins ont été uninéphrectomisées et traitées avec de l’eau du robinet. Les animaux ont reçu soit l’antagoniste des récepteurs ETA, atrasentan (5 mg·jour−1·kg−1 de poids corporel) ou un véhicule. Les souris DOCA-sel ont montré une augmentation de pression artérielle systolique (PAS), et le traitement par atrasentan a diminué la PAS chez ces souris. Les réponses contractiles à l’ET-1, à la phényléphrine et à une stimulation de champ électrique (SCÉ, stimulation nerveuse adrénergique) ont été accrues dans les bandelettes provenant des souris DOCA-sel, alors que les relaxations en réponse à l’IRL-1620 (agoniste des récepteurs ETB), à une SCÉ (stimulation nerveuse non adrénergiquenon cholinergique), à l’acétylcholine et au nitroprussiate de sodium n’ont pas été modifiées. PD59089 (inhibiteur de ERK1/2 ), mais pas Y-27632 (inhibiteur de la Rho-kinase), a supprimé les contractions stimulées par l’ET-1 dans le corps caverneux des souris DOCA-sel. Le traitement des souris par l’antagoniste des récepteurs ETA, atrasentan, n’a pas normalizeé la réponses caverneuses. En résumé, le traitement par DOCA-sel chez les souris augmente la réactivité caverneuse aux stimuli contractiles, mais pas aux stimuli relaxants, par des mécanismes indépendants du rapport ET-1/ETA.

Mots-clés : endothéline-1, récepteur ETA, Rho-kinase, hypertension DOCA-sel, corps caverneux, ERK1/2, atrasentan. [Traduit par la Rédaction]

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL71138 and HL74167) and Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil.

Abbreviations

- DOCA-salt

deoxycorticosterone acetate and salt

- EC50

the molar concentration of agonist producing 50% of the maximum response

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- Emax

maximum effect elicited by the agonist

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- ETA

endothelin receptor subtype A

- ETB

endothelin receptor subtype B

- IRL-1620

succinyl-[Glu9,Ala11,15]-endothelin-1(8–21)

- l-NAME

Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- NANC

nonadrenergic noncholinergic

- pD2

negative logarithm of EC50

- PD59089

2-(2-amino-3-methoxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one

- PE

phenylephrine

- Y-27632

trans-4-((1R)-1-aminoethyl)-N-4-pyridinylcyclohexanecarboxamide dihydrochloride.

Footnotes

This article is one of a selection of papers published in the special issue (part 1 of 2) on Forefronts in Endothelin.

Contributor Information

Fernando S. Carneiro, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA; Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Fernanda R.C. Giachini, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA; Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Victor V. Lima, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA.

Zidonia N. Carneiro, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA.

Kênia P. Nunes, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA; Department of Physiology, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG-Brazil.

Adviye Ergul, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA..

Romulo Leite, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA..

Rita C. Tostes, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA; Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil.

R. Clinton Webb, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Physiology, 1120 Fifteenth Street, CA-3141, Augusta, GA 30912-3000, USA..

References

- Andersson KE. Pharmacology of penile erection. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:417–450. PMID:11546836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KE. Erectile physiological and pathophysiological pathways involved in erectile dysfunction. J. Urol. 2003;170:S6–S14. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000075362.08363.a4. PMID:12853766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki H, Richmond M, Izumo S, Sadoshima J. Specific role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vitro. Biochem. J. 2000;347:275–284. PMID:10727428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ari G, Vardi Y, Hoffman A, Finberg JP. Possible role for endothelins in penile erection. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;307:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00172-0. PMID:8831106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg SA, Hansen-Schwartz JA, Vikman PJ, Xu CB, Edvinsson LI. ERK1/2 inhibition attenuates cerebral blood flow reduction and abolishes ET(B) and 5-HT(1B) receptor upregulation after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:846–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600236. PMID:16251886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CR, Sullivan ME, Dashwood MR, Muddle JR, Morgan RJ. The density and distribution of endothelin 1 and endothelin receptor subtypes in normal and diabetic rat corpus cavernosum. Br. J. Urol. 1995;76:203–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07675.x. PMID:7663911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchio M, Desideri G, Scarpelli P, Necozione S, Properzi G, Spartera C, et al. Endothelial cell activation in men with erectile dysfunction without cardiovascular risk factors and overt vascular damage. J. Urol. 2004;171:1601–1604. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000116325.06572.85. PMID:15017230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callera GE, Touyz RM, Teixeira SA, Muscara MN, Carvalho MH, Fortes ZB, et al. ETA receptor blockade decreases vascular superoxide generation in DOCA-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:811–817. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000088363.65943.6C. PMID:12913063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitaley K, Webb RC, Dorrance AM, Mills TM. Decreased penile erection in DOCA-salt and stroke prone-spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2001;13 Suppl 5:S16–S20. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900773. PMID:11781742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ GJ, Lerner SE, Kim DC, Melman A. Endothelin-1 as a putative modulator of erectile dysfunction: I. Characteristics of contraction of isolated corporal tissue strips. J. Urol. 1995;153:1998–2003. PMID:7752383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Pollock DM, Lewis RL, Wingard CJ, Stopper VS, Mills TM. Receptor-specific influence of endothelin-1 in the erectile response of the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;279:R25–R30. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R25. PMID:10896860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Melegy NT, Ali ME, Awad EM. Plasma levels of endothelin-1, angiotensin II, nitric oxide and prostaglandin E in the venous and cavernosal blood of patients with erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2005;96:1079–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05780.x. PMID:16225532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanueli C, Fink E, Milia AF, Salis MB, Conti M, Demontis MP, Madeddu P. Enhanced blood pressure sensitivity to deoxycorticosterone in mice with disruption of bradykinin B2 receptor gene. Hypertension. 1998;31:1278–1283. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.6.1278. PMID:9622142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granchi S, Vannelli GB, Vignozzi L, Crescioli C, Ferruzzi P, Mancina R, et al. Expression and regulation of endothelin-1 and its receptors in human penile smooth muscle cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2002;8:1053–1064. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.12.1053. PMID:12468637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamed EA, Meki AR, Gaafar AA, Hamed SA. Role of some vasoactive mediators in patients with erectile dysfunction: their relationship with angiotensin-converting enzyme and growth hormone. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2003;15:418–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901059. PMID:14671660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner A, Cordasic N, Klanke B, Veelken R, Hilgers KF. Strain differences in the development of hypertension and glomerular lesions induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate salt in mice. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2003;18:1999–2004. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg299. PMID:13679473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson M, Xu CB, Edvinsson L. Importance of ERK1/2 in upregulation of endothelin type B receptors in cerebral arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;142:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705803. PMID:15237095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist F, Kirkeby HJ, Larsson B, Forman A, Andersson KE. Functional effects, binding sites and immunolocalization of endothelin-1 in isolated penile tissues from man and rabbit. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:795–802. PMID:1578385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanabe Y, Masaki T, Hashimoto N. Involvement of epidermal growth factor receptor-protein tyrosine kinase transactivation in endothelin-1-induced vascular contraction. J. Neurosurg. 2004;100:1066–1071. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.6.1066. PMID:15200122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Thompson CS, Angelini GD, Morgan RJ, Mikhailidis DP, Jeremy JY. Prostaglandins and cyclic nucleotides in the urinary bladder of a rabbit model of partial bladder outlet obstruction. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 1999;61:307–314. doi: 10.1054/plef.1999.0105. PMID:10670693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite R, Giachini FRC, Carneiro FS, Nunes KP, Tostes RC, Webb RC. Targets for the treatment of erectile dysfunction: is NO/cGMP still the answer? Recent Patents Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2007;2:119–132. doi: 10.2174/157489007780832579. PMID:18221110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RW. Definitions, classification, and epidemiology of sexual dysfunction. In: Lue TFB, Rosen R, Giuliano F, Khoury S, Montorsi F, editors. Sexual Medicine: Sexual Dysfunction in Men and Women. Paris: Health Publications; 2004. pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mills TM, Chitaley K, Wingard CJ, Lewis RW, Webb RC. Effect of Rho-kinase inhibition on vasoconstriction in the penile circulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:1269–1273. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1269. PMID:11509525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Mulhall JP. Cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome and erectile dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2006;16:435–443. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000250284.83108.a6. PMID:17053524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson D, Wackenfors A, Gustafsson L, Paulsson P, Ingemansson R, Edvinsson L, Malmsjö M. Endothelin receptor mediated vasodilatation: effects of organ culture. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;579:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.031. PMID:17964568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkkisenniemi UM, Klinge E. Functional characterization of endothelin receptors in the bovine retractor penis and penile artery. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;79:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1996.tb00245.x. PMID:8878249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Carretero OA, Alfie ME, Julie A, Masura JA, Rhaleb NE. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist in deoxycorti-costerone acetate–salt hypertensive mice lacking Ren-2 gene. Hypertension. 2001;37:974–980. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.3.974. PMID:11244026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Rivera AA, Fink GD, Galligan JJ. Vascular reactivity of mesenteric arteries and veins to endothelin-1 in a murine model of high blood pressure. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2005;43:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.02.014. PMID:15975530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz de Tejada I, Carson MP, De las Morenas A, Goldstein I, Traish AM. Endothelin: localization, synthesis, activity, and receptor types in human penile corpus cavernosum. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;261:H1078–H1085. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.4.H1078. PMID:1656784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoia C, Schiffrin EL. Vascular inflammation in hypertension and diabetes: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2007;112:375–384. doi: 10.1042/CS20060247. PMID:17324119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin EL. Vascular endothelin in hypertension. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2005;43:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.03.004. PMID:15955745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer F, Klotz T, Steinritz D, Schmidt A, Addicks K, Engelmann U, Bloch W. MAP kinase 1/2 (Erk 1/2) and serine/threonine specific protein kinase Akt/PKB expression and activity in the human corpus cavernosum. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2002;14:217–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900856. PMID:12152110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ME, Dashwood MR, Thomson CS, Muddle JR, Mikhailidis DP, Morgan RJ. Alterations in endothelin B receptor sites in cavernosal tissue of diabetic rabbits: potential relevance to the pathogenesis of erectile dysfunction. J. Urol. 1997;158:1966–1972. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64195-8. PMID:9334651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tostes RC, Muscara MN. Endothelin receptor antagonists: another potential alternative for cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Drug Targets Cardiovasc. Haematol. Disord. 2005;5:287–301. doi: 10.2174/1568006054553390. PMID:16101562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tostes RC, Giachini FR, Carneiro FS, Leite R, Inscho EW, Webb RC. Determination of adenosine effects and adenosine receptors in murine corpus cavernosum. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;322:678–685. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.122705. PMID:17494861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingard CJ, Husain S, Williams J, James S. RhoA-Rho kinase mediates synergistic ET-1 and phenylephrine contraction of rat corpus cavernosum. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003;285:R1145–R1152. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00329.2003. PMID:12893655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]