Abstract

The present study describes a protocol to generate heterogenous populations of neurotransmitter-producing neurons from human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). MSCs are bone marrow (BM)-derived cells which undergo lineage- specific differentiation to generate bone, fat, cartilage and muscle, but are also capable of transdifferentiating into defined ectodermal and endodermal tissues. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the potential of MSCs as an alternative source of customized neurons for experimental neurobiology or other regenerative approaches. Our neuronal protocol utilizes freshly harvested human MSCs cultured on specific surfaces and exposed to an induction cocktail consisting of low serum concentration, retinoic acid (RA), growth factors and supplements. Here we report on the types of neurotransmitters produced by the neurons, and demonstrate that the cells are electrically responsive to exogenous neurotransmitter administration.

Indexing terms: Mesenchymal stem cells, Gamma-aminobutyric acid

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells hold tremendous potential in advancing the treatment of many diseases and disorders that are currently untreatable (1-4). Presently, the utilization of stem cells in neural tissue repair or replacement has been limited. However, a continued understanding of stem cell biology and the pathology of neural diseases may lead to future clinical therapies.

Stem cells, whether embryonic (ESC) or adult (ASC), have other applications, such as providing models to study disease/injury or in drug screening (5-8). In particular, the generation of neurons from stem cells affords the unique opportunity to study human neural processes in primary cells. However, customized protocols must be established to generate specific classes of neurotransmitter-producing cells.

We have previously reported the generation of functional neurons transdifferentiated from human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (9, 10). However, while our previous reports investigated the feasibility for neuronal transdifferentiation from MSCs, the current study elucidates in great detail the protocol to generate these cells, as well as classifies the types of neurons produced. Additionally, our laboratory has reported the transdifferentiation of MSCs into dopamine progenitor cells using a separate induction protocol (11).

MSCs are mesoderm-derived cells primarily resident to the adult bone marrow (BM), which undergo lineage- specific differentiation along adipogenic, chondrogenic and osteogenic paths (12, 13). MSCs are attractive candidates in tissue repair medicine given their relative ease in harvesting, isolation and expansion (14). MSCs also possess defined transcriptional mechanisms that may be responsible for their observed plasticity, since they have been shown to generate cells of both endoderm and ectoderm (15-19).

In the present report, we investigated the neurotransmitter phenotype displayed by the MSC-derived neurons generated from our protocol. We previously identified several key neurotransmitter genes upregulated in the neurons using a microarray-based approach (10). These studies formed the impetus to validate the classes of neurotransmitters produced by these neurons at the protein level, and to identify whether certain neurotransmitters were unique to specific subpopulations of neurons or homogenously expressed. We also examined whether the neurons were excitable in response to exogenously applied neurotransmitters through electrophysiological studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with high glucose, DMEM/F12, L-glutamine and B-27 supplement were purchased from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal calf serum (FCS), all-trans retinoic acid (RA), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate and Ficoll-Hypaque were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Defined fetal calf serum was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). Recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dilactate (DAPI) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA). Recombinant human IL-1α was obtained from Hoffman La Roche (Nutley, NJ).

Rabbit anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), -leu-enkephalin (Leu-Enk), -tyrosine hydroxylase (TyrH), -glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), -glutamate, goat anti-tryptophan hydroxylase (TrypH) and NMDA receptor monocolonal antibody (mAb) were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA), synaptic vesicle 2 (SV2) protein and synaptophysin (Syn) mAbs from Novocastra (Newcastle, UK), rabbit anti-vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), -vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) and β-Actin mAb from Sigma, goat anti-GABAA receptor-β1 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and rabbit anti-substance P (SP) from Biogenesis (Kingston, NH). FITC-goat anti-mouse was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA) and PE-goat anti-rabbit from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). Horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit, -goat and -mouse IgG were purchased from Sigma.

Culture of Human MSCs

MSCs were cultured from BM aspirates as described (10, 20). The use of human BM aspirates followed a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Newark campus. Unfractionated BM aspirates (2 ml) were diluted in 12 ml of DMEM containing 10% FCS (D10 media) and then transferred to vacuum-gas plasma treated, tissue culture Falcon 3003 petri dishes. Plates were incubated, and at day 3, mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll Hypaque density gradient and then replaced in the culture plates. Fifty percent of media was replaced with fresh D10 media at weekly intervals until the adherent cells were approximately 80% confluent. After four cell passages, the adherent cells were asymmetric, CD14–, CD29+, CD44+, CD34–, CD45–, SH2+, prolyl-4-hydroxylase– (20).

At approximately 70-80% confluence, MSCs were trypsinized and then subcultured in 60-mm Falcon 3002 petri dishes or on round Fisherbrand microscope selected cover glass placed in 35-mm Falcon 3001 dishes (Fischer Scientific, Springfield, NJ). At 20% confluence, D10 media was replaced with neuronal induction medium (NIM), which comprised of Ham's DMEM/F12, 2% FCS (Sigma), B27 supplement, 20 mM RA and 12.5 ng/ml bFGF. The media was unchanged during the entire period of induction, maximum of 12 days.

Western Analysis and Immunoprecipitation

Whole cell extracts were prepared from D6 and D12 induced MSCs, or uninduced MSCs (D0) as described (10). Briefly, cells were trypsinized, resuspended in 1x Lysis Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and subjected to freeze/thaw cycles in a dry ice/ethanol bath. Cell-free, whole cell lysates were obtained and total protein was determined with a Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Hercules, CA). Whole cell extracts (20 µg) were analyzed by western blots using 4-20% SDS-PAGE pre-cast gels (Bio-Rad) and the proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). Human brain extract (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) (20 µg) served as positive control for neurotransmitter expression. Membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies and then detected the following day by 2-h incubation with HRP-conjugated IgG. All primary and secondary antibodies were used at final dilutions of 1/1000 and 1/2000, respectively. HRP was developed with chemilluminescence detection reagent (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences). The membranes were stripped with Restore Stripping Buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for reprobing with other antibodies.

VIP and CGRP were immunoprecipitated from the growth medium (1 ml) of D0, D6 and D12 cells (approximately 104 cells) using the Catch and Release® v2.0 Reversible Immunoprecipitation System (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Charlottesville, VA) according to manufacturer's specific guidelines. Immunoprecipitants (40 µl) were assayed for total protein concentration and then analyzed by western analysis, as described above.

Immunofluorescence

Uninduced (D0) and induced (up to D12) MSCs were established on glass coverslips placed in 35-mm culture dishes. On the day of immunofluoresence labeling, the cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 5 min. This was followed by permeabilization in 1% Triton-X. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies: SV2 and Syn mAb at final concentrations of 1/100; and rabbit anti-CGRP, -SP, -glutamate and -GAD at final concentrations of 1/250. Antibodies were diluted in 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS. Primary antibodies were developed with secondary FITC-goat anti-mouse and PE-goat anti-rabbit, at final concentrations of 1/500. Secondary antibodies were diluted in 0.1% BSA/PBS and incubated for 2 h in the dark at room temperature. For dual-labeling of cells for SP and GAD, rabbit anti-GAD was conjugated to fluorescein using the fluorescein protein labeling kit (Pierce). Cells labeled solely with PE- and FITC-IgG served as isotype controls. Following labeling, cell nuclei were counter-stained with 300 nM DAPI diluted in 0.1% BSA/PBS. Cover slips were immediately transferred to glass coverslides and examined on a three-color fluorescent microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melvelle, NY). Fluorescence intensities were calculated using UN-SCAN-IT software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (2 µg) was reverse transcribed, and 200 ng of cDNA was used in PCR to amplify GABAAR-β1 and NMDAR1. The primers for GABAAR-β1 and NMDAR1 span +872/+1415 (NM_000812) and +542/+969 (NM_000832), respectively. PCR was done with the following primer pairs: GABAAR-β1 (forward) 5' cct ggg tgt ctt ttt gga 3' and (reverse) 5' tcg ggg atc ttg act ttg 3'; and NMDAR1 (forward) 5' cca tcc aga tgg ctc tgt 3' and (reverse) 5' ctc ttt cgc ctc cat cag 3'. PCR reactions were normalized by amplifying the same sample of cDNA with primers specific for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GAPDH. The primers for GAPDH span +212/+809 (NM_002046), with the following sequences: (forward) 5' cca ccc atg gca aat tcc atg gca 3' and 5' tct aga cgg cag gtc agg tcc acc 3'. The cycling profile for GABAAR-β1 and NMDAR1 (35 cycles), and GAPDH (25 cycles) was: 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR reactions (10 µ1) were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose containing ethidium bromide. Band sizes were compared with 1 kb DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

FM 1-43FX Synaptic Vesicle Stain

FM 1-43FX synaptic stain was purchased from Molecular Probes. The procedure followed manufacturer's suggested guidelines, as described previously (10). Briefly, a working solution of the dye was prepared at 5 µg/mL in ice cold PBS. D12 induced MSCs, established on glass coverslips placed in 35-mm culture dishes were washed with PBS. After this, the cells were incubated for 1 min with equal amounts of dye for plasma membrane labeling (1 ml). Cells were investigated for dye reuptake within intracellular vesicles by concurrent 1 min administration of 1 mM GABA or 1 mM glutamate. Excess dye was aspirated and the cells were fixed with ice-cold 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min. Cell nuclei were counter-stained with 300 nM DAPI and immediately examined on a three-color fluorescent microscope. Administration of 1% BSA/PBS served as a vehicle control.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Whole-cell configuration was used to record electrical activity with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster city, CA), via a Digidata 1322A analog-to-digital converter (Axon Instruments), and pClamp 9.2 software (Axon Instruments). Data were filtered at 1 kHz and sampled at 5 kHz.

D12 cells were transferred to a 35-mm culture dish filled with a standard external solution containing: 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM

HEPES, and 10 mM glucose (320 mOsm, pH set to 7.3 with Tris-base). The patch electrodes had a resistance of 3-5 MW, when filled with pipette solution containing: 140 mM CsCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 4 mM EGTA, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM Mg-ATP, and 0.1 mM GTP. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with Tris-base, and the osmolarity was adjusted to 280-300 mOsm with sucrose. Drugs (GABA, glutamate) were added to the superfusate applied to the cell using a fast perfusion system (Y-tube). Solutions in the vicinity of a neuron can be completely exchanged within 40 ms without damaging the seal. All electrophysiological recordings were performed at room temperature (22-24°C).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical data analyses were performed with analysis of variance and Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Production and packaging of neuropeptides by induced MSCs

We have previously reported on the transdifferentiation of MSCs into neurons (10). However, the study only briefly investigated the types of neurotransmitters produced by the neurons through microarray analyses (10). This preliminary data demonstrated that MSCs induced to form neurons for 12 days (D12) upregulated genes specific for peptidergic, GABAergic and cholinergic neurons (Table 1) (10). Additionally, we found that D12 cells were capable of biosynthesis and release of the neuropeptide, SP, upon stimulation with the pro-inflammatory cytokine,IL-1α (24).

Table 1.

Neurotransmitter genes upregulated in MSC-derived neurons.

| Neurotransmitter | Endogenous Source | Physiological Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetycholine | Central/peripheral nervous system | Excitatory, skeletal muscle contraction, synaptic plasticity | (10, 21) |

| GABA | Central nervous system | Inhibitory or excitatory, brain development | (10, 22) |

| Neuropeptides | Central/peripheral nervous system | Synaptogenesis, glial morphology, tumorigenesis | (10, 23>) |

Classes of neurotransmitter genes that have been shown to be upregulated in MSC-derived neurons through a microarray approach (10). Except for the neuropeptide, SP, validation at the protein level was not previously studied.

We further explored our previous findings by assessing the types of neurons produced by our induction protocol. The first set of studies examined whether SP is packaged into synaptic vesicles. Uninduced (D0) and induced (D12) MSCs were stimulated with IL-1α, then co-labeled for SP and synaptic vesicle 2 (SV2) protein or synaptophysin (Syn), and studied by immunofluorescence (Fig. 1A). D12 cells expressed both synaptic proteins (SV2 –second row, first panel; Syn –fourth row, first panel), and SP (second and fourth rows, second panel), with co-localization throughout the cell body and neurites (Merge –second and fourth rows, fourth panel). Approximately 61% of D12 cells were positive for SP expression. In contrast, SV2, Syn

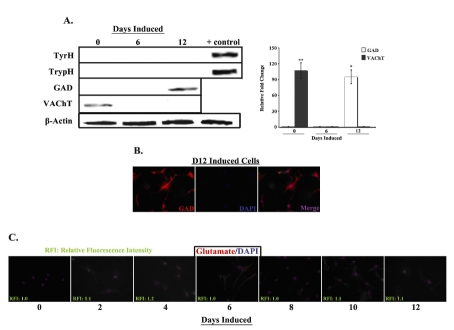

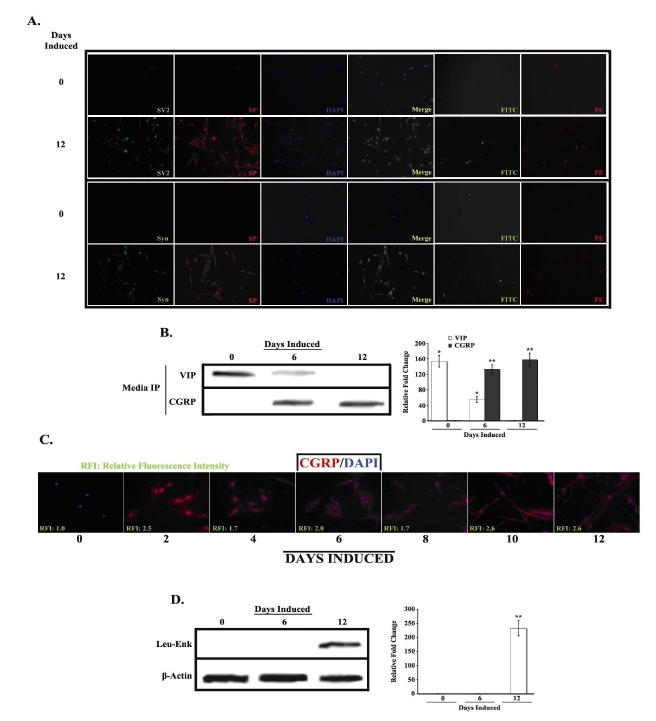

Fig. 1. Neuropeptide expression in uninduced and induced MSCs.

A. Uninduced (D0) and induced (D12) MSCs were co-labeled with PE-anti-SP and FITC-anti-SV2 or FITC-anti-synaptophysin (Syn), and then counterlabeled with nucleus-specific DAPI. Figure shows representative labelings of five different experiments. Images are shown at 10X magnification. B. Media from uninduced (D0) and induced (D6 and D12) MSCs was immunoprecipitated with anti-VIP and anti-CGRP and then analyzed by western blot. Representative blots are shown for three different experiments. Band densities were quantified and normalized to total protein. Results are presented as mean ± SD relative fold change, where the lowest value is arbitrarily assigned a value of 1. C. Uninduced and induced MSCs were labeled at 2 day intervals, up to 12 days, with PE-anti-CGRP and then counterlabeled with DAPI. Relative fluorescence intensities were normalized to values for uninduced cells, which were arbitrarily assigned a value of 1. Figure shows representative labelings of five different experiments. Images are shown at 10X magnification. D. Whole cell extracts from D0, D6 and D12 cells were prepared and analyzed by western blots with anti-Leu-Enkephalin. Normalizations were performed with anti-β-actin. Representative blots are shown for three different experiments. Band quantification was performed as in B *p<0.05 vs. D12 induced cells **p<0.05 vs. uninduced cells

We next determined whether induced MSCs synthesize and/or release other neuropeptides, specifically VIP, CGRP and Leu-Enk (Figs. 1B-1D). Western analyses of cellular extracts from uninduced and induced MSCs showed low to undetectable levels of VIP and CGRP (data not shown). We therefore assayed the growth media to determine whether these neuropeptides were being released (Fig. 1B). Immunoprecipitation of VIP from the media showed elevated levels in the uninduced MSCs (D0), with a gradual decrease in production during neuronal induction (top row, white bars). Interestingly, the opposite results were found for CGRP, with intracellular (Fig. 1C) and extracellular (Fig. 1B, bottow row, gray bars) levels increasing during induction and peaking in the D12 cells. These results are consistent with previous findings, which show synaptic co-localization of CGRP and SP (25). As was observed for CGRP, Leu-Enk expression was only detected in induced MSCs, specifically D12 cells (Fig. 1D, white bar).

Production of other neurotransmitters by induced MSCs

Our laboratory has recently developed a separate neuronal induction protocol specific for the generation of dopaminergic neurons from human MSCs (11). We therefore examined whether the presently described protocol also produces neuronal cells capable of non-peptidergic neurotransmitter biosynthesis. To this end, expression of the rate-limiting enzymes in catecholamine (TyrH), serotonin (TrypH) and GABA (GAD) biosynthesis, as well as the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT), were examined in uninduced (D0) and induced (D6 and D12) MSCs (Fig. 2A). The expression of TyrH and TrypH was undetectable in both uninduced and induced cells (first and second rows) compared to human brain extract controls (first and second rows, far right column). In contrast, a light band was detectable in D12 extracts for GAD (third row, far right column, white bar) and D0 extracts for VAChT (fourth row, far left column, gray bar).

Fig. 2. Expression of CNS neurotransmitters in uninduced and induced MSCs.

A. Whole cell extracts from uninduced (D0) and induced (D6 and D12) MSCs were prepared and analyzed by western blots with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TyrH), -tryptophan hydroxylase (TrypH), -glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) and -vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT). Normalizations were performed with anti-β-actin. Human brain extract served as positive control. Representative blots are shown for three different experiments. Band densities were quantified and normalized to total protein. Results are presented as mean ± SD relative fold change, where the lowest value is arbitrarily assigned a value of 1. B. D12 induced cells were labeled with PE-anti-GAD and then counter-labeled with DAPI. Figure shows representative labelings of five different experiments. Images are shown at 20X magnification. C. Uninduced and induced MSCs were labeled at 2 day intervals, up to 12 days, with PE-anti-glutamate and then counterlabeled with DAPI. Relative fluorescence intensities were normalized to values for uninduced cells, which were arbitrarily assigned a value of 1. Figure shows representative labelings of five different experiments. Images are shown at 10X magnification.*p<0.05 vs. uninduced cells **p<0.05 vs. D12 induced cells

To determine the percentage of D12 cells expressing GAD, we performed immunofluorescence studies in uninduced and induced MSCs (Fig. 2B). Only a minority of D12 cells was found to express GAD (22 ± 3.2%), whereas GAD expression was undetectable in uninduced D0 and induced D6 cells (data not shown). Because glutamate is the substrate for GAD-mediated GABA biosynthesis, we examined MSCs for glutamate expression during the entire course of neuronal induction (Fig. 2C). Low to undetectable levels of glutamate were observed in the induced cells, with no expression detected in the uninduced cells (far left panel).

In summary, a population of D12 cells was found to express GAD, whereas the rate-limiting enzymes in catecholamine and serotonin biosynthesis, and the acetylcholine transporter, were not detected. Low to basal levels of glutamate were found in the induced cells, thus potentially limiting the availability of substrate for GABA biosynthesis.

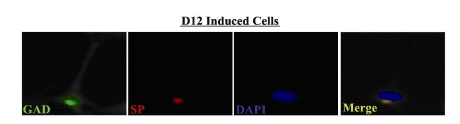

Distinct populations of SP+ and GAD+ neuronal cells

The next set of studies asked whether the peptidergic (SP+) and putative GABAergic (GAD+) neurons existed as distinct sub-populations, or whether some cells were capable of producing both neurotransmitters. To address this question, we co-labeled D12 induced MSCs for GAD (green) and SP (red) expression and observed the cells by immunofluorescence (Fig. 3). Very few cells (<1%) were found to co-express SP and GAD (Merge –far right panel). The results suggest that the peptidergic and putative GABAergic cells primarily exist as two distinct sub-populations.

Fig. 3. Colocalization of SP and GAD in induced MSCs.

D12 cells were co-labeled with FITC-anti-GAD and PE-anti-SP, and then counter-labeled with DAPI. Figure shows representative labelings of five different experiments. Images are shown at 40X magnification

Neurotransmitter-evoked responses in D12 induced cells

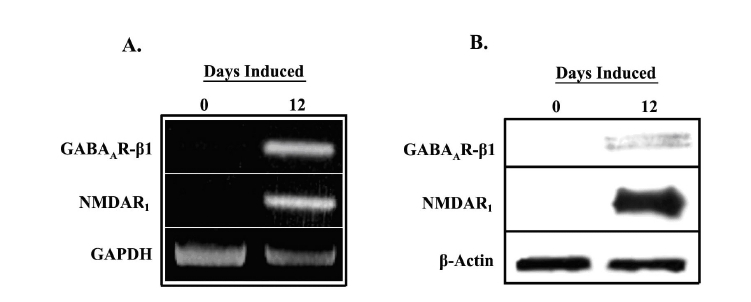

We have previously shown that D12 induced MSCs are capable of releasing neurotransmitter in response to membrane depolarization by KCl (10). However, one hallmark of mature neurons that we have not previously investigated is neurotransmitter-evoked currents. Within the central nervous system, the main neurotransmitters are glutamate and GABA, with glutamate being excitatory and GABA being inhibitory. We therefore determined whether the D12 induced cells could respond to glutamate and GABA treatment.ionotrophic glutamate receptor, NMDA, and a subunit of the GABAA receptor, GABAAR-β1, in uninduced and D12 induced cells (Fig. 4). Distinct bands were observed in D12 cells for GABAA (top panel) and NMDA (middle panel) receptor mRNA (Fig. 4A) and protein (Fig. 4B), while bands were undetectable for uninduced cells. Interestingly, although there appeared to be a large increase in GABAAR-β1 mRNA in the D12 cells, this did not seem to be reflected accurately at the protein level. One explanation for this observation could be the large number of cycles (35) used to amplify GABAAR-β1 mRNA. Additionally, GABAAR-β1 may only be expressed on the small population of cells expressing GAD, therefore its levels in a whole cell preparation may be reduced.

Fig. 4. Expression of GABA and glutamate receptors in uninduced (D0) and induced (D12) MSCs. A.

Total RNA from D0 and D12 cells was studied for expression of the GABAA A receptor β1 subunit and NMDA1 receptor by RT-PCR. Normalizations were performed with oligonucleotides specific for GAPDH. Representative gel is shown for three different experiments. B. Whole cell extracts from D0 and D12 cells were prepared and analyzed by western blots with anti-GABAAR-β1 and anti-NMDAR1. Normalizations were performed with anti-β-actin. Representative blots are shown for three different experiments.

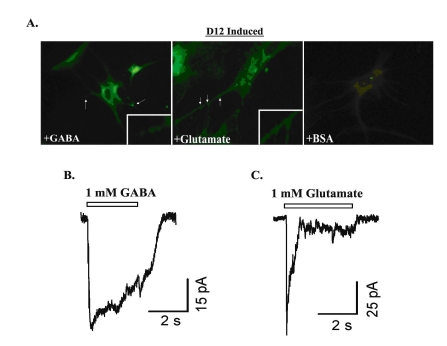

Next, we investigated whether the D12 induced cells are capable of releasing neurotransmitters in response to glutamate or GABA treatment. For this experiment, D12 cells were incubated with the membrane dye, FM1-43 FX, as previously reported (Fig. 5A) (10). Cells undergoing exocytotic vesicular release in response to treatment will show a pattern of punctate staining along the neurites, thus indicating vesicular recycling following synaptic release. D12 cells treated for 1 min with GABA (left panel) or glutamate (middle panel) possessed cellular processes demonstrating a pattern of staining consistent with vesicular dye reuptake. Cells treated with vehicle control (BSA; right panel) did not exhibit a similar staining pattern. As shown previously, pre-conditioning with a calcium chelator such as EDTA inhibited vesicular release and dye reuptake (data not shown) (10).

Fig. 5. GABA and glutamate elicit responses in D12 induced MSCs.

A. FM1-43 FX lipophilic plasma membrane dye was added at 5 µg/mL to D12 cells. Cells were cultured on glass coverslips, with dye incubation lasting for 1 min. Cells were fixed with ice-cold 3.7% formaldehyde and then examined for plasma membrane staining. Intracellular vesicle dye reuptake was studied by treating cells with 1 mM GABA (left panel) or 1 mM glutamate (middle panel) following labeling. Vehicle controls used 1% BSA (right panel). Figure represents four different experiments, each performed with cells from a different donor. Representative inward currents elicited by 1 mM GABA (B) or 1 mM glutamate (C) from cells in culture for 12 days. The peak amplitude is 49 pA for GABA-induced current, and 81 pA for glutamate-induced current. Whole-cell currents were recorded at a holding potential of -50 mV

The final set of studies examined whether D12 induced cells exhibit an electrophysiological response to exogenous glutamate or GABA (Fig. 5B and 5C). For these experiments, whole-cell currents were recorded from D12 cells voltage-clamped at a holding potential of -60 mV. The application of either 1 mM GABA (Fig. 5B) or glutamate (Fig. 5C) induced inward currents. In 3 of 12 D12 induced cells examined, 1 mM GABA induced an inward current of 512 ± 274pA and 1 mM glutamate of 52 ± 14 pA. GABA and glutamate induced no current in 10 studied cells induced for 8 days (data not shown).

In summary, D12 induced MSCs express receptors for both glutamate and GABA (Fig. 4). These receptors appear to be functional, since administration of either neurotransmitter elicited a response, as determined by cellular and electrophysiological approaches (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

In this study we report on the heterogeneous phenotype displayed by human MSC-derived neurons. We have previously demonstrated that MSC-derived neurons undergo a neurogenic program of differentiation, with observation of mature and functional neuronal attributes following 12 days induction (10). However, this study did not characterize the types of neurons produced by the induction protocol (10). The present study examined the

neurotransmitter phenotype of the neurons, and determined their excitability upon exogenous neurotransmitter administration. Interestingly, we observed two distinct classes of neurotransmitter producing cells; (1) peptidergic and (2) putative GABAergic neurons, a percentage of which were excitable in the presence of exogenously applied glutamate or GABA.

We have previously shown that 12-day induced MSCs (D12 cells) synthesize the neurotransmitter SP following stimulation with the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1α (24). It could be argued that since IL-1α is necessary to induce SP production (Fig. 1A), perhaps similar stimulation is necessary to induce the production of other neurotransmitters not found in the present study. However, D12 cells express mRNA for the gene encoding SP (TAC1) prior to IL-1α stimulation (24). Translation is halted by the presence of specific miRNAs which transiently inhibit SP production (26). This level of regulation is alleviated by stimulation with IL-1α (26). Since peptidergic and GABAergic transcripts were principally detected in previous microarray studies, these neurotransmitters were investigated in greater detail (Figs. 1 and 2) (10).

Interestingly, we observed production of several neuropeptides during the course of neuronal induction (Fig. 1). VIP was synthesized by uninduced cells, while D12 cells produced CGRP and Leu-Enk, as well as SP. These findings are logical, since CGRP and SP have been shown to co-localize and have immunostimulatory functions, while VIP is generally immunosuppressive (25, 27). Although immunoprecipitated culture media was analyzed, we have reported similar results intracellularly (28).

We assessed the presence of other, non-peptidergic, neurotransmitters in induced cells by examining the rate-limiting enzymes in neurotransmitter biosynthesis (TyrH, TrypH, GAD), transport proteins (VAChT) or the neurotransmitter itself (glutamate) (Fig. 2). Only GAD, the rate-limiting enzyme in GABA biosynthesis, was upregulated in the D12 cells (Fig. 2A). These findings were interesting, since GABA is principally found within the central nervous system, while MSCs are linked to the peripheral nervous system within the BM. Neuropeptide production would appear to be more characteristic of neurons derived from MSCs than GABA. However, GABA production was not specifically measured, since accurately determining its levels is difficult due to instability. Further assessment of stored and released GABA is necessary to confidently demonstrate a GABAergic phenotype.

Colocalization of SP and GABA within synaptic boutons has been well established within the brain, yet only a small percentage of D12 cells were found to co-express the transmitters (Fig. 3) (29, 30). These results seem to indicate two distinct populations of cells. However, it is entirely possible; given the small punctuate immunoreactivity for SP in these cells (Fig. 3), that this is a result of SP reuptake from the media and not co-localization.

These findings suggest that two distinct sub-populations (peptidergic and GABAergic) of cells exist. In order to clearly separate the new sub-populations from parental cells, it would be interesting to examine cell surface markers such as CD14, CD29, CD44, CD34, CD45, SH2, in addition to SP and GAD. A difference in expression may indicate that some parental cells are more apt to form peptidergic rather than GABAerigic cells.

Other evidence of heterogeneity is apparent from studying the excitability of the induced cells (Figs. 4 and 5). One hallmark of the newly derived neurons should be excitability in response to exogenous glutamate or GABA administration. Although the cells were found to express both protein and transcript for the glutamate and GABA receptors (Fig. 4), we recorded GABA- or glutamate-elicited currents in only 25% of the D12 cells (Fig. 5). Another interesting observation was that we did not observe a GABA or glutamate response at concentrations of less than 1 mM. Physiologically, this dose is very high (although, in the synapses, the normal concentrations are > 1mM), and indicates that the D12 cells may not be fully mature.

A possible explanation for the heterogeneity found within the D12 cells is that MSCs themselves are inherently heterogeneous in vitro. Our laboratory has recently shown that this heterogeneity increases with the number of cell passages (15). Heterogeneity is not something that would be beneficial when applying neurons derived from MSCs to specific diseases. Ideally, a pure population of well-defined neurons and possibly supportive cells, such as glia, would seem to be best suited for neural regeneration or repair. We have recently generated an induction protocol specific for the generation of dopaminergic progenitor cells from human MSCs (11). This research may be useful in application towards diseases that specifically target the destruction of dopaminergic neurons, such as Parkinson's.

The findings of the present study are particularly significant and may be useful in understanding how to formulate new induction protocols towards the generation of other specific types of neurons from human MSCs. By understanding the heterogeneity within MSC cultures we may be able to formulate improved methods for producing pure neuronal populations. Such advancements could provide a supply of "off-the-shelf" stem cells, tailor-made to treat many different neurological conditions.

In summary, the present report demonstrates that our current neuronal induction protocol generates a phenotypically heterogenous population of neurons, which show neurotransmitter-evoked excitability in a small percentage of cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the F.M. Kirby Foundation.

Protocols

Reagents

DMEM with high glucose

Ham's F12 media

L-glutamine

B-27 supplement

fetal calf serum

retinoic acid

Ficoll-Hypaque

bFGF

Falcon 3003, 3002, 3001 petri dishes

Fisherbrand microscope selected cover glass

Preparation of Media

Preparation of Media

10% defined FCS in DMEM with high glucose and glutamate

Differentiation Medium

Ham's F12 media with 2% FCS, supplemented with B27 (final concentration 1x), 20 mM RA and 12.5 ng/ml bFGF

Stock solution of RA should be diluted in DMSO to 20 mM

Isolation and Culture of MSCs

Dilute unfractionated BM aspirates (2 ml) in 12 ml of DMEM containing 10% FCS (D10 media) and then transfer to vacuum-gas plasma treated, tissue culture Falcon 3003 petri dishes.

Incubate plates at 37°C.

At day 3, isolate mononuclear cells by Ficoll Hypaque density gradient (buffy coat layer) and then replate in the same cultures.

Replace 50% of media at weekly intervals with fresh D10 media until the adherent cells are approximately 80% confluent.

Trypsinize and subculture at a ratio of 1:3 to 1:6.

After 4 cell passages the adherent cells should be asymmetric, and display the following phenotype: CD14–, CD29+, CD44+, CD34–, CD45–, SH2+, prolyl-4-hydroxylase-.

Neuronal Induction of MSCs

At approximately 70-80% confluence, and between passages 3 and 10, trypsinize MSCs and then subculture in 60-mm Falcon 3002 petri dishes or on round Fisherbrand microscope selected cover glass placed in 35-mm Falcon 3001 dishes.

For western analysis seed 104 MSCs in 60-mm tissue culture dishes. For immunofluorescence, seed 103 MSCs in 35-mm tissue culture dishes on glass coverslips.

Allow cells to adhere to the culture surface overnight at 37°C in D10 media.

At 20% confluence, replace D10 media with neuronal induction medium (see preparation of differentiation medium).

In parallel, culture MSCs in media alone with vehicle used for reconstitution of RA and growth factors. These cells shall serve as vehicle control.

Leave media unchanged during the entire period of induction, maximum of 12 days.

All experimental endpoints should be performed with a maximal confluence of 70% to control for contact inhibition.

Experimental endpoints should be 6 and 12 days induction, which correspond to partially differentiated and fully differentiated neuronal phenotype.

REFERENCES

- Korecka JA, Verhaagen J, Hol EM. Cell-replacement and gene-therapy strategies for Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. Regen Med. 2007;2:425–446. doi: 10.2217/17460751.2.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silani V, Corbo M. Cell-replacement therapy with stem cells in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2004;1:283–289. doi: 10.2174/1567202043362243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher AA, Schlechta B, Gasparovicova A, Wolner E, Bonaros N, Laufer G. Stem cells and cardiac regeneration. Transpl Int. 2007;20:731–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock LT, Tzanakakis ES. Stem/Progenitor cell sources of insulin-producing cells for the treatment of diabetes. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1399–1412. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler B, Edenhofer F, Brüstle O. Merging fields: stem cells in neurogenesis, transplantation, and disease modeling. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:155–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.00010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Scientific and clinical opportunities for modeling blood disorders with embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2006;107:2605–2612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HY Ho, Li M. Potential application of embryonic stem cells in Parkinson's disease: drug screening and cell therapy. Regen Med. 2006;1:175–182. doi: 10.2217/17460751.1.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks C, Halse R, Suzuki R, Shepherd PR. Human cell systems for drug discovery. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2003;6:570–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KJ, Trzaska KA, Greco SJ, McArdle J, Wang FS, Ye JH, Rameshwar P. Neurons derived from human mesenchymal stem cells show synaptic transmission and can be induced to produce the neurotransmitter substance P by interleukin-1 alpha. Stem Cells. 2005;23:383–391. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco SJ, Zhou C, Ye JH, Rameshwar P. An interdisciplinary approach and characterization of neuronal cells transdifferentiated from human mesenchymal stem cells. . Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:811–826. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzaska KA, Kuzhikandathil EV, Rameshwar P. Specification of a dopaminergic phenotype from adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2797–2808. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P, Riminucci M, Gronthos S, Robey PG. Bone marrow stromal stem cells: nature, biology, and potential applications. Stem Cells. 2001;19:180–192. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-3-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans RJ, Moseley AB. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology and potential clinical uses. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javazon EH, Beggs KJ, Flake AW. Mesenchymal stem cells: paradoxes of passaging. . Exp Hematol. 2004;32:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco SJ, Greco K, Rameshwar P. Functional similarities among genes regulated by OCT4 in human mesenchymal and embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3143–3154. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SJ, Oshima K, Heller S, Edge AS. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells are progenitors in vitro for inner ear hair cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt M, Salmon P, von Mach MA, Hengstler JG, Brulport M, Linscheid P, Seboek D, Oberholzer D, Barbero A, Martin I, et al. Multipotential nestin and Isl-1 positive mesenchymal stem cells isolated from human pancreatic islets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KS, Shin JS, Lee JJ, Kim YS, Kim SB, Kim CW. In vitro trans-differentiation of rat mesenchymal cells into insulin-producing cells by rat pancreatic extract. In vitro trans-differentiation of rat mesenchymal cells into insulin-producing cells by rat pancreatic extract. 2005;330:1299–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SY, Dai H, Leong KW. Inducing hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in pellet culture. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4087–4097. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potian JA, Aviv H, Ponzio NM, Harrison JS, Rameshwar P. Veto-like activity of mesenchymal stem cells: Functional discrimination between cellular responses to alloantigens and recall antigens. J Immunol. 2003;171:3426–3434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME. Neuromodulation and cortical function: Modeling the physiological basis of behavior. Behav Brain Res. 1995;67:1–27. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00113-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möhler H, Fritschy JM, Crestani F, Hensch T, Rudolph U. Specific GABA(A) circuits in brain development and therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1685–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco SJ, Corcoran KE, KE KJ, Rameshwar P. Tachykinins in the emerging immune system: relevance to bone marrow homeostasis and maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1782–1793. doi: 10.2741/1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco SJ, Rameshwar P. Enhancing effect of IL-1alpha on neurogenesis from adult human mesenchymal stem cells: implication for inflammatory mediators in regenerative medicine. J Immunol. 2007;179:3342–3350. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma QP, Hill R, Sirinathsinghji D. Colocalization of CGRP with 5-HT1B/1D receptors and substance P in trigeminal ganglion neurons in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:2099–2104. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco SJ, Rameshwar P. miRNAs regulate synthesis of the neurotransmitter substance P in human mesenchymal stem cell-derived neuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15484–15489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703037104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganea D, Gonzalez-Rey E, Delgado M. A novel mechanism for immunosuppression: from neuropeptides to regulatory T cells. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:400–409. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo MD, Trzaska KA, Greco SJ, Ponzio NM, Rameshwar P. Immunostimulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived neurons: Implications for stem cell therapy in allogeneic transplantations. Clin Transl Sci. 2008;1:27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu N, Yamamoto K, Higuchi S, Fukuda T. An immunohistochemical study on a unique colocalization relationship between substance P and GABA in the central nucleus of amygdala. Brain Res. 2008;1198C:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CO, Bullock D. Neuropeptide co-release with GABA may explain functional non-monotonic uncertainty responses in dopamine neurons. . Neurosci Lett. 2008;430:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]