Abstract

Multidrug resistance (Mdr) transporters are ATP-binding cassette transporters that efflux amphipathic cations from cells and protect tissues from xenobiotics. Unfortunately, Mdr transporters also efflux anticancer drugs from some tumor cells, resulting in multidrug resistance. There are two groups of Mdrs in mice: group I includes Mdr1a and Mdr1b that transport xenobiotics, whereas group II is Mdr2, a flipase that facilitates phospholipid excretion into bile. Little is known about the regulation of Mdr genes in vivo. The purpose of this study was to determine tissue distribution, gender differences, ontogeny, and chemical induction of Mdrs in mice. The mRNA of Mdr1a is highest in gastrointestinal tract, Mdr1b in ovary and placenta, and Mdr2 in liver. Both Mdr1a and Mdr1b in kidney show female-predominant expression patterns due to repression by androgens. The ontogeny of mouse Mdr1a in duodenum and brain as well as Mdr1b in brain, kidney, and liver all share a similar developmental pattern: low expression at birth, followed by a gradual increase to mature levels at approximately 30 days of age. In contrast, Mdr2 mRNA in liver is markedly up-regulated at birth, which returns to low levels by 5 days of age and then gradually increases to mature levels. None of the Mdrs in liver are readily inducible by any class of microsomal enzyme inducers. In conclusion, the three Mdr transporters in mice are expressed in a tissue-specific and age-dependent pattern, there are gender differences in expression, and Mdr transporters are inducible by only a few microsomal enzyme inducers.

Multidrug resistance transporters (AbcB1 family), also termed “P-glycoproteins,” were originally discovered in human (MDR1) and rodent (Mdr1a and Mdr1b) cancer cell lines, in which they were markedly up-regulated (Bradley et al., 1988). They function as efflux pumps with broad substrate profiles, including many chemotherapeutic drugs, hence the name “multidrug resistance.” In contrast, Mdr2 (AbcB2) is a flipase, which effluxes phospholipids from the inner to the outer membrane of the bile canaliculus (Smit et al., 1993). Phospholipids protect the biliary tree against bile acids, and they also form micelles with bile acids, which promote the absorption of lipid and lipid-soluble vitamins from the GI tract.

Little is known about the in vivo regulation of the mouse Mdr family of transporters. Tissue distribution and chemical induction of Mdrs in rats have been characterized previously (Brady et al., 2002). However, because mice are becoming a more commonly used experimental model due to the availability of knockout animals, it is important to determine the expression pattern and regulation of the Mdrs in mice.

Expression of Mdr transporters among tissues reflects the vulnerability of various tissues to Mdr substrates upon chemical exposure. The human MDR1 gene is expressed highly in the brush border of enterocytes, indicating its role in protecting the organism from some orally exposed xenobiotics (Thiebaut et al., 1987). Mouse Mdrs have been found in the intestinal epithelium, capillaries of brain and testis, adrenal gland, and ovaries (Buschman et al., 1992). However, a more specific approach is needed to probe for the different isoforms of the mouse Mdrs, and a quantitative comparison is desired to compare the expression of Mdrs among various tissues. The branched DNA amplification technology has been shown to have high specificity, linearity, and efficiency (Hartley and Klaassen, 2000).

Gender-divergent expression of transporters and drug-metabolizing enzymes may result in differences in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of chemicals between males and females. Endocrine signals may be responsible for such differences. Sex hormones (5α-dihydroxytesterone in males and 11β-estradiol in females) as well as secretion patterns of growth hormone are different between males and females. Male-patterned growth hormone consists of spikes in GH release, followed by troughs in which GH is virtually absent; female-patterned growth hormone is secreted in a consistent, pulsatile pattern, with relatively high troughs compared with those in males. Previous work in this laboratory has revealed gender-divergent expression of several mouse transporters in vivo, including some of the organic anion-transporting polypeptide uptake transporters and the multidrug resistance-associated protein efflux transporters, which have gender-divergent expression in liver, kidney, or both (Cheng et al., 2005, 2006; Maher et al., 2005). These gender differences were due to sex hormones, growth hormone secretory patterns, or both. Whether gender-divergent expression also occurs in the Mdr transporter family remains unknown; therefore, the expression patterns of mouse male and female Mdrs as well as the mechanisms of regulation will be determined in the present study.

Neonates are generally considered to be more susceptible to xenobiotics than adults, which in part might be due to less efficient drug metabolism and transport. In addition, infants have unique metabolic pathways compared with adults. For example, different isoforms of cytochrome P450 enzymes are found in human infants and adults (Tateishi et al., 1997). Therefore, in the present study, the ontogenic patterns of the mouse Mdr transporters are determined, which provides insight into drug transport capacities at different ages.

Microsomal enzyme inducers (MEIs) are transcription factor activators. Once activated by the MEI, these transcription factors are translocated into the nucleus, which increases the expression of some genes. The transcription factors AhR, CAR, PXR, PPARα, and Nrf2 are generally considered as xenobiotics sensors, which can up-regulate various phase I and phase II drug-metabolizing enzymes. Limited evidence exists for the interactions of microsomal enzyme inducers with the Mdr efflux transporters. We hypothesize that these ligands may also up-regulate the expression of Mdr transporters.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine 1) the tissue distribution of the three Mdr genes in mice, namely, Mdr1a, Mdr1b, and Mdr2, by quantifying the mRNA levels in 13 important metabolic tissues; 2) whether there are gender differences in mouse Mdr expression, and if so, the mechanisms; 3) the ontogeny patterns of the mRNA of the three Mdr transporters; and 4) the inductility of the Mdrs by microsomal enzyme inducers.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) was a gift from Dr. Karl Rozman (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS). Oltipraz was a gift from Dr. Steven Safe (Texas A&M University, College Station, TX). Polychlorinated biphenyl 126 (PCB126) was obtained from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Mice. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) to study the tissue distribution, gender differences, ontogeny, and chemical induction of Mdrs. For the gender differences study, hypophysectomized and gonadectomized C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA); growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor-deficient (lit-lit) mice were also purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. For chemical induction of Mdrs, five groups of microsomal enzyme inducers (15 chemicals in total) were administered to mice for 4 days (intraperitoneally) as described previously (Cheng et al., 2005). Tissues were collected 24 h after the final dosing.

Tissue Distribution. Eight-week-old male and female mice were housed according to the American Animal Association Laboratory Animal Care guidelines. Twelve tissues (liver, kidney, lung, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, heart, brain, testis, and ovary) were collected. Placenta was removed from pregnant mice on gestation day 17. The tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen. The intestine was longitudinally dissected, rinsed in saline, and divided into three equal-length sections (referred to as duodenum, jejunum, and ileum), before being frozen in liquid nitrogen. All tissues were stored at –80°C.

Ontogeny. Mice were bred in the animal facilities at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Brain, duodenum, kidney, and liver from male and female mice were collected at postnatal days –2, 0, 5, 10 15, 22, 30, 35, 40, and 45 (n = 5/gender/age).

Gender Differences in Kidney. First, mice were gonadectomized on day 37 of age, followed by replacement with 5α-dihydroxytestosterone (DHT; 5-mg 21-day-release pellets, subcutaneously for 10 days), 11β-estradiol (E2; 0.5-mg 21-day-release pellets, subcutaneously for 10 days), or placebo. Second, mice were hypophysectomized on day 30 of age, followed by replacement with female-patterned growth hormone (1-mg 21-day-release pellets, subcutaneously for 10 days) or male-patterned growth hormone (rat growth hormone, 2 times daily, 2.5 mg/kg i.p. for 10 days). Finally, lit-lit mice were administered a placebo, male-patterned growth hormone or female-patterned growth hormone. Kidneys were collected from gonadectomized, hypophysectomized, and GHRH receptor-deficient mice. Tissues were stored at –80°C.

Chemical Induction. Treatment groups with five mice in each were administered one of the following chemicals once daily for 4 days: AhR ligands, TCDD (40 μg/kg i.p. in corn oil), β-naphthoflavone (BNF; 200 mg/kg i.p. in corn oil), and PCB126 (300 μg/kg p.o. in corn oil); CAR activators, PB (100 mg/kg i.p. in saline), TCPOBOP (3 mg/kg i.p. in corn oil), and diallyl sulfide (DAS; 200 mg/kg i.p. in corn oil); PXR ligands, PCN (200 mg/kg i.p. in corn oil), spironolactone (SPR; 200 mg/kg i.p. in corn oil), and dexamethasone (75 mg/kg i.p. in corn oil); PPARα ligands, clofibric acid (CLFB; 500 mg/kg i.p. in saline), ciprofibric acid (CPFB; 40 mg/kg i.p. in saline), and diethylhexylphthalate (DEHP; 1000 mg/kg p.o. in corn oil); and Nrf2 activators, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA; 350 mg/kg i.p. in corn oil), ethoxyquin (250 mg/kg p.o. in corn oil), and oltipraz (OPZ; 150 mg/kg p.o. in corn oil). Three different vehicle control groups (corn oil by intraperitoneal, corn oil by gavage, and saline by intraperitoneal route) were used. All injections were administered in a volume of 10 ml/kg. Tissues were removed on day 5, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80°C.

RNA Isolation. Total RNA was isolated using RNAzol B reagent (Tel-Test Inc., Friendswood, TX) per the manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentrations were quantified by ultraviolet absorbance at 260 nm.

Branched DNA Signal Amplification Assay. Mouse Mdr mRNA was quantified by the bDNA assay (QuantiGene bDNA signal amplification kit; Panomics, Fremont, CA). Specific oligonucleotide probe sets of Mdr1a, Mdr1b, and Mdr2 were synthesized by QIAGEN Operon (Alameda, CA) and reported as described previously (Cheng and Klaassen, 2006). Ten micrograms of total RNA was added to each well of a 96-well plate. Mdr mRNA was captured by the probe sets and attached to a branched DNA amplifier. Enzymatic reactions occur upon substrate exposure, and the luminescence for each well is reported as relative light units.

Statistics. Statistical differences between genders were determined by Student's t test. Differences between multiple groups were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan's post hoc test. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Results

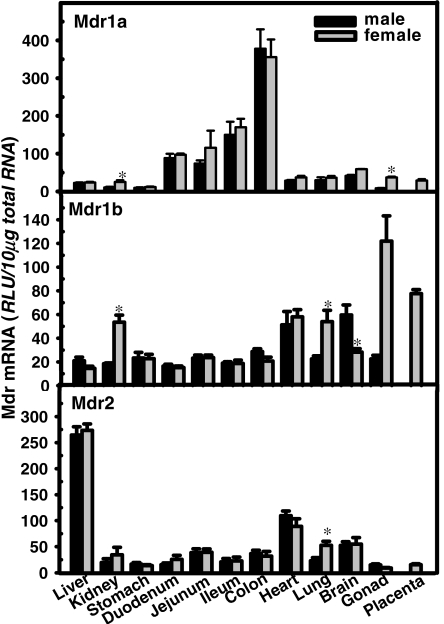

Tissue Distribution of Mouse Mdrs. The mRNA expression of the three Mdrs in 13 mouse tissues was quantified as shown in Fig. 1. The expression of Mdr1a mRNA (Fig. 1, top) is highest in the gastrointestinal tract, with levels increasing along the GI tract from stomach to colon [stomach (3%), duodenum (25%), jejunum (26%), ileum (43%), and colon (100%)]. Compared with the highest expression level in colon (100%), the expression of Mdr1a mRNA in other tissues, namely, liver (6%), kidney (5%), lung (9%), heart (9%), gonads (6%), and placenta (8%), was all less than 1/10 of that in colon; the brain Mdr1a mRNA is relatively higher (14%).

Fig. 1.

Tissue distribution of mouse Mdr1a (top), Mdr1b (middle), and Mdr2 (bottom) mRNA. Total RNA from 13 tissues (liver, kidney, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, heart, lung, brain, testis, ovary, and placenta) in C57BL/6 mice at (n = 5/gender) was analyzed by the bDNA assay for Mdr1a, Mdr1b, and Mdr2 mRNA expression. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences between male and female mice computed by Student's t test (p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

Mdr1b mRNA is high in ovary and placenta, and it is expressed in kidney, heart, lung, and brain at intermediate levels. The highest level of expression of mouse Mdr1b mRNA is in ovary (100%), closely followed by that in placenta (64%). In comparison, testis has much lower expression of Mdr1b mRNA (20%). Moderate expression levels of Mdr1b mRNA were also observed in heart (45%), brain (36%), kidney (30%), and lung (30%). The expression of Mdr1b mRNA in the gastrointestinal tract is duodenum (13%), ileum (15%), jejunum (19%), stomach (19%), and colon (20%). Mdr2 mRNA is predominantly expressed in liver, but it is also expressed in heart (38.5%) and brain (23%).

Gender Differences in Mouse Mdrs. As shown in Fig. 1, gender-divergent expression of Mdrs was observed in the following tissues: Mdr1a and Mdr1b mRNA in kidney; Mdr1b and Mdr2 in lung, and Mdr1b in brain. In kidney, both Mdr1a and Mdr1b have a female-dominant expression pattern, as does Mdr1b and Mdr2 mRNA in lung. In contrast, the expression of Mdr1b in brain is male-dominant. Because kidney is a major site for drug elimination, the effects of hormones on kidney Mdr1a and Mdr1b are studied as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

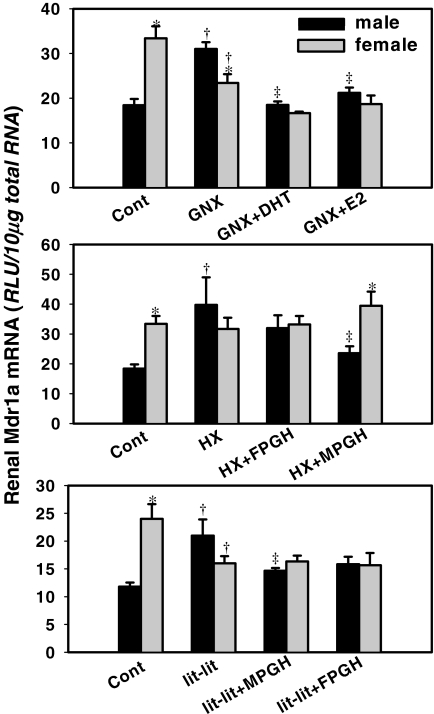

Fig. 2.

Hormone effects on the expression of Mdr1a in kidney. Top, kidneys were collected from naive mice (Cont), gonadectomized mice replaced with placebo (GNX), gonadectomized mice replaced with DHT (GNX+DHT), and gonadectomized mice treated with E2 (GNX+E2). Middle, kidneys from naive mice (Cont), hypophysectomized mice replaced with placebo (HX), hypophysectomized mice replaced with female-patterned growth hormone (HX+FPGH), and hypophysectomized mice replaced with male-patterned growth hormone (HX+MPGH). Bottom, kidneys from naive mice (Cont), lit-lit mice replaced with placebo (lit-lit), lit-lit mice replaced with male-patterned growth hormone (lit-lit+MPGH), and lit-lit mice replaced with female-patterned growth hormone (lit-lit+FPGH). Total RNA was isolated, and Mdr1a mRNA levels were quantified by bDNA assay. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences between male and female mice computed by Student's t test (p < 0.05). Single daggers (†) indicate statistically significant differences compared with naive mice. Double daggers (‡) indicate statistically significant differences compared with the placebo-treated surgery groups (GNX, HX, or lit-lit) (ANOVA, followed by Duncan's post hoc test, p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

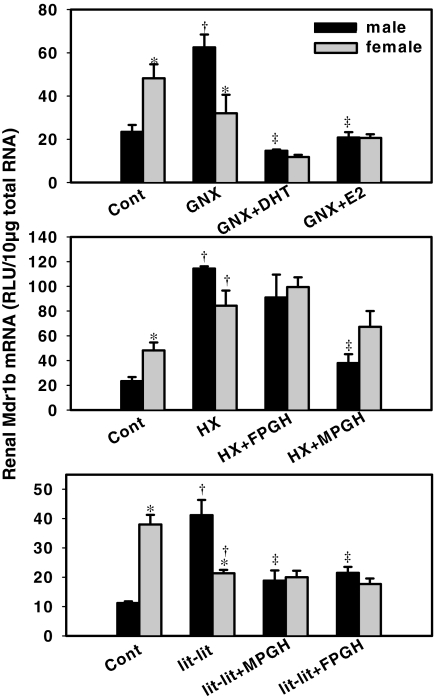

Fig. 3.

Hormone effects on the expression of Mdr1b in kidney. Top, kidneys were collected from naive mice (Cont), gonadectomized mice replaced with placebo (GNX), gonadectomized mice replaced with DHT (GNX+DHT), and gonadectomized mice treated with E2 (GNX+E2). Middle, kidneys from naive mice (Cont), hypophysectomized mice replaced with placebo (HX), hypophysectomized mice replaced with female-patterned growth hormone (HX+FPGH), and hypophysectomized mice replaced with male patterned growth hormone (HX+MPGH). Bottom, kidneys from naive mice (Cont), lit-lit mice replaced with placebo (lit-lit), lit-lit mice replaced with male-patterned growth hormone (lit-lit+MPGH), and lit-lit mice replaced with female-patterned growth hormone (lit-lit+FPGH). Total RNA was isolated and Mdr1b mRNA levels were quantified by bDNA assay. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences between male and female mice computed by a Student's t test (p < 0.05). Single daggers (†) indicate statistically significant differences compared with naive mice. Double daggers (‡) indicate statistically significant differences compared with the placebo-treated surgery groups (GNX, HX, or lit-lit) (ANOVA, followed by Duncan's post hoc test, p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

Effects of Gonadectomy, Hypophysectomy, and lit-lit on Mdr1a mRNA Expression. Mdr1a mRNA was 83% higher in female than in male kidney (Fig. 2, top). Gonadectomy increased Mdr1a mRNA in male mice (177% of control) and decreased Mdr1a mRNA in female mice (70% of control) and thus abolished the female-predominant expression pattern. Compared with gonadectomy alone, administration of DHT decreased Mdr1a mRNA in castrated mice (56% of gonadectomized male mice). Administration of E2 also decreased Mdr1a mRNA in castrated mice (66% of gonadectomized male mice), but it did not alter Mdr1a expression in ovariectomized mice. Together, these data suggest that male sex hormone inhibits the expression of male Mdr1a in kidney.

Hypophysectomy increased Mdr1a mRNA in male mouse kidney (200% of control), but it did not alter Mdr1a mRNA in female mice (Fig. 2, middle), and thus it abolished the female-predominant expression pattern. Compared with hypophysectomy alone, administration of female-patterned GH did not change Mdr1a mRNA expression in male or female mice. Administration of male-patterned growth hormone decreased Mdr1a mRNA in male (58% of hypophysectomized male mice), but it did not alter the female Mdr1a mRNA. In summary, male-patterned growth hormone inhibits Mdr1a expression in male kidney. lit-lit increased Mdr1a mRNA in male mouse kidney (175% of control), but it decreased Mdr1a mRNA in female mouse kidney (67% of control) (Fig. 2, bottom). Compared with vehicle-treated lit-lit mice, administration of male-patterned GH to the lit-lit mice decreased Mdr1a mRNA in male mice (71% of lit-lit male mice), but it did not change Mdr1a mRNA expression in female lit-lit mice. Administration of female-patterned GH did not alter either male or female Mdr1a mRNA expression.

Taken together, the female-predominant expression of Mdr1a mRNA in kidney of mice seems to be due to the inhibitory effect by androgens. The administration of male-patterned growth hormone decreased Mdr1a mRNA in kidneys of male mice, probably through elevating androgen levels.

Effects of Gonadectomy, Hypophysectomy, and lit-lit on Mdr1b mRNA Expression. Mdr1b mRNA was 117% higher in female than in male kidney (Fig. 3, top). Gonadectomy increased Mdr1b mRNA in castrated mice (270% of control), but it did not alter Mdr1b mRNA in ovariectomized mice. Compared with gonadectomy alone, administration of DHT decreased Mdr1b mRNA in kidneys of castrated mice (26% of gonadectomized male), but it did not alter Mdr1b mRNA in ovariectomized mice. Administration of E2 also decreased Mdr1b mRNA in kidneys of castrated mice (32% of gonadectomized female), but it did not alter it in ovariectomized mice. Together, these data indicate that androgen inhibits the expression of Mdr1b in kidneys.

Hypophysectomy increased Mdr1b mRNA in kidneys of both male mice (500% of control) and female mice (170% of control) (Fig. 3, middle). Administration of female-patterned growth hormone to hypophysectomized mice did not alter Mdr1b mRNA in male or female kidneys, but male-patterned GH decreased male Mdr1b mRNA in kidneys of hypophysectomized mice (35% of hypophysectomized male). Together, these data suggest that male-patterned growth hormone inhibits Mdr1b expression in mouse kidneys.

In contrast with control wild-type mice, Mdr1b mRNA was higher in male than female lit-lit mice (Fig. 3, bottom). Administration of male-patterned GH and female-patterned GH to lit-lit mice both decreased Mdr1b mRNA in kidneys of male (48 and 58% of lit-lit male, respectively), but not in female mice. Administration of male-patterned growth hormone also decreased Mdr1a and Mdr1b mRNA in males, probably through an indirect effect by elevating androgen levels. In summary, the female-predominant expression of both Mdr1a and Mdr1b in kidneys of mice seems to be due to inhibitory effect by androgen.

Ontogeny of Mdr1a in Mouse Duodenum. Duodenum is the first section of the small intestine and thus first exposed to xenobiotics and other chemicals in the intestine. In addition, duodenum is also the first section of the GI tract to come in contact with bile acids secreted from the liver. During development, duodenum is the first section of the intestine that senses changes in the diets from maternal milk to standard fiber-enriched chow. Therefore, duodenum was selected to examine the ontogeny of Mdr1a, even though its expression is not as high as in ileum and colon. The developmental pattern of Mdr1a in mouse duodenum is shown in Fig. 4 (top, first panel). Because no gender differences in Mdr1a was observed in duodenum, male and female tissues were combined at each age. There was minimal expression of Mdr1a in mouse duodenum prenatally. After birth, the Mdr1a mRNA expression increased in a time-dependent manner, which exhibited a peak (17-fold of day –2 levels) at 15 days of age, followed by a decrease thereafter.

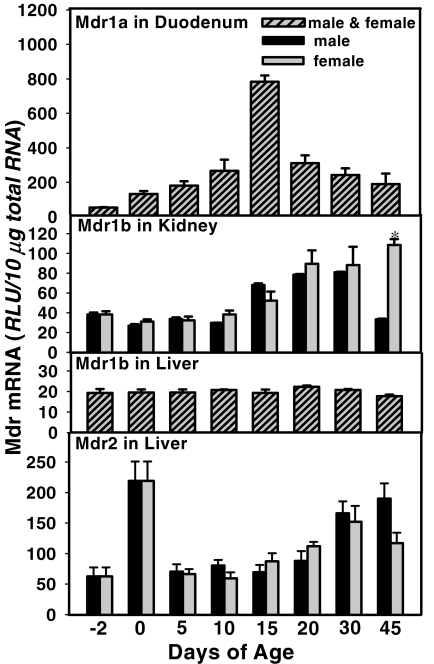

Fig. 4.

Ontogeny of mouse Mdr1a in duodenum, Mdr1b in kidney and liver, and Mdr2 in liver. Total RNA from mice at each age (n = 5/gender) was analyzed by the bDNA assay. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between male and female mice computed by Student's t test (p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

Ontogeny of Mdrs in Mouse Kidney and Liver. Mdr1b is crucial for renal excretion of some chemicals, because it transports xenobiotics from proximal tubular cells into the lumen. The development patterns of Mdr1b in male and female mouse kidney are shown in Fig. 4 (second panel). There was low expression of Mdr1b in mouse kidneys before 15 days of age in both male and female mice. After day 10, both male and female mouse Mdr1b mRNA expression in kidneys increased (approximately 150% of day –2 levels) until 30 days of age, when they reached their maximal expression levels, which are at least 2-fold higher than that at birth. After 30 days of age, there was a sharp decrease in male Mdr1b mRNA expression in kidney, whereas it remained high in female mice.

Mdr1b was low in adult liver as shown in Fig. 1. During development, Mdr1b in liver is consistently expressed at a low and steady level (Fig. 4, third panel).

The developmental pattern of Mdr2 in mouse liver is shown in Fig. 4 (bottom, fourth panel). Low expression of Mdr2 mRNA in mouse liver was noted 2 days before birth. At birth, the expression level increased approximately 3-fold, followed by a dramatic decrease to before birth levels by day 5 of age, which then gradually returned to adult levels (approximately 3-fold of day –2 levels) by 1 month of age.

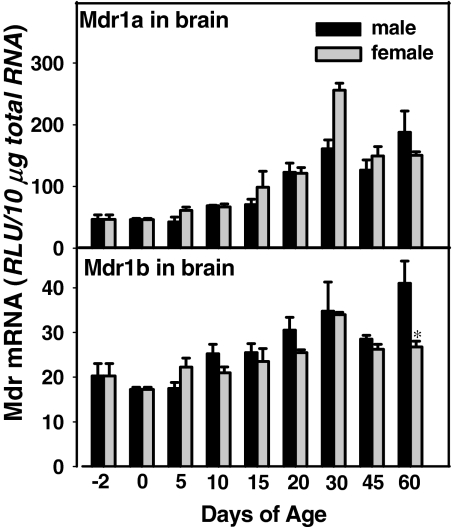

Ontogeny of Mdr1a and 1b in Mouse Brain. The blood-brain barrier is important to protect the brain from excessive chemical exposure. Mdr transporters are expressed in the endothelial cells of the brain and thus serve a protective role for the brain. The developmental patterns of Mdr1a and 1b in male and female mouse brain are shown in Fig. 5. Mdr1a and 1b mRNA in male and female mice share similar developmental patterns. Minimal expression of Mdrs was observed 2 days before as well as the first 10 days of age in both male and female mice. The Mdr1a and 1b mRNA expression levels increased thereafter in both male and female mice, and they reached their mature levels at 30 days of age. Between birth and 6 weeks of age, there is approximately a 200% increase in Mdr1a and only a 50% increase in Mdr1b.

Fig. 5.

Ontogeny of mouse Mdr1a and 1b in brain. Total RNA from mice at each age (n = 5/gender) was analyzed by the bDNA assay. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between male and female mice computed by Student's t test (p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

Chemical Induction of Mdrs. Fifteen chemicals, which fall into five groups of transcription factor activators (also known as microsomal enzyme inducers), were used at doses shown in Table 1. Because the inducers are not necessarily specific for one transcription factor, for example, BNF is an AhR activator but can be metabolized to an Nrf2 activator (Huang et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2006), three inducers were used per transcription factor, to generate more confidence that the induction is probably mediated by a certain transcription factor. The chemical induction of the three Mdrs was studied in liver, brain, and duodenum. No statistical difference in mRNA expression was observed among the three vehicle-treated groups (corn oil by intraperitoneal, corn oil by gavage, and saline intraperitoneal route). Therefore, these three control groups were averaged as a single vehicle control group.

TABLE 1.

Nuclear receptors and their targeting ligands (MEIs)

| Transcription Factor | MEIs |

|---|---|

| AhR | TCDD, BNF, PCB126 |

| CAR | PB, TCPOBOP, DAS |

| PXR | PCN, SPR, DEX |

| PPARα | CLFB, CPFB, DEHP |

| Nrf2 | BHA, EXQ, OPZ |

DEX, dexamethasone; EXQ, ethoxyquin.

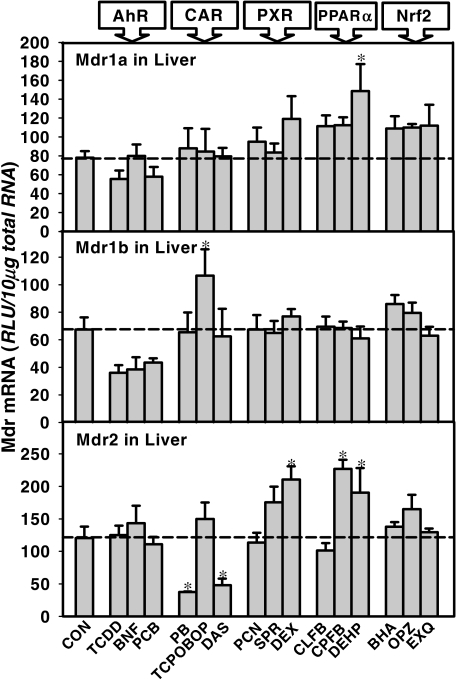

The effect of microsomal enzyme inducers on the Mdr mRNAs in mouse liver is shown in Fig. 6. Overall, none of the Mdrs were induced by any entire class of microsomal enzyme inducer. Only a few ligands induced Mdrs, namely, the PPARα ligand DEHP induced Mdr1a (187% of control), the CAR ligand TCPOBOP induced Mdr1b (154% of control), and the PPARα ligands CPFB and DEHP induced Mdr2 in liver (192 and 160% of control, respectively).

Fig. 6.

Effects of chemical induction on C57BL/6 mouse Mdr1a mRNA expression in brain, duodenum, and liver. The dose of chemical treatment was described under Materials and Methods. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistically significant increase in mRNA level after treatment compared with the control group computed by ANOVA (p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

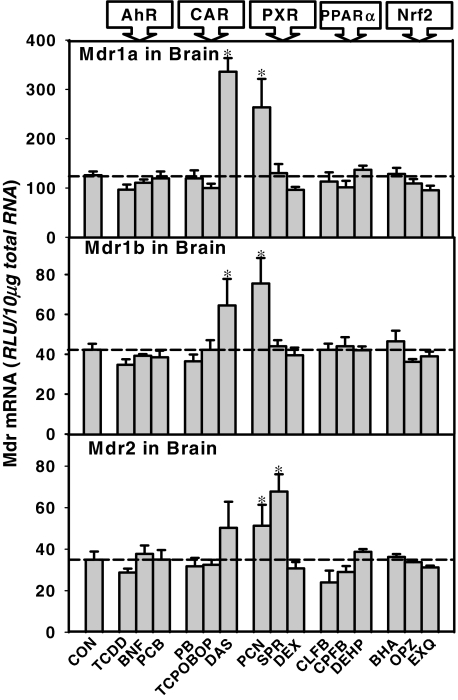

The effect of microsomal enzyme inducers on the Mdr mRNAs in mouse brain is shown in Fig. 7. The CAR ligand DAS induced both Mdr1a (267% of control) and Mdr1b mRNA (150% of control). The PXR ligand PCN induced all three Mdrs (Mdr1a, 220% of control; Mdr1b 200% of control; and Mdr2, 150% of control). Another PXR ligand, SPR, induced Mdr2 in brain (200%).

Fig. 7.

Effects of chemical induction on C57BL/6 mouse Mdr1b mRNA expression in brain, duodenum, and liver. The dose of chemical treatment was described under Materials and Methods. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistically significant increase in mRNA level after treatment compared with the control group computed by ANOVA (p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

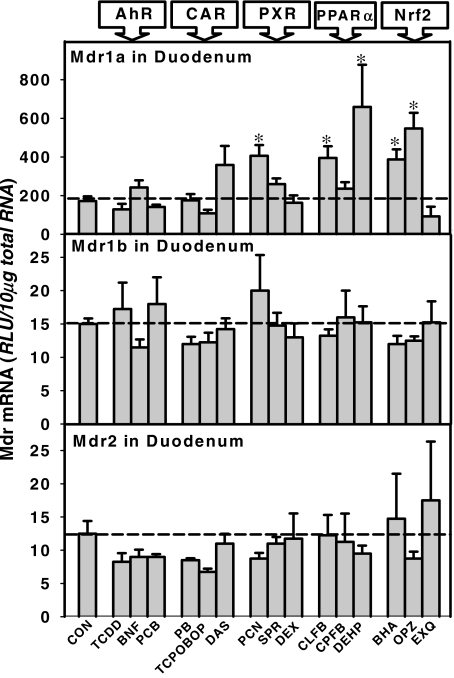

The induction of Mdr mRNAs in mouse duodenum is shown in Fig. 8. Neither Mdr1b nor Mdr2 seemed to be inducible in the duodenum by any MEI. Mdr1a mRNA was induced by the PXR ligand PCN (200%), by PPARα ligands CLFB (200%) and DEHP (300%), and by Nrf2 activators BHA (200%) and OPZ (225%) but not by any entire class of MEI.

Fig. 8.

Effects of chemical induction on C57BL/6 mouse Mdr2 mRNA expression in brain, duodenum, and liver. The dose of chemical treatment was described under Materials and Methods. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistically significant increase in mRNA level after treatment compared with the control group computed by ANOVA (p < 0.05). RLU, relative light units.

Discussion

Mdr1 transporters are key molecules in determining not only the resistance of cancer cells against chemotherapeutic drugs but also the disposition of a variety of drugs in intestine and other tissues. The mouse tissue with the highest Mdr1a mRNA is colon, which probably indicates its high capability to excrete toxicants. The human ortholog for mouse Mdr1a is MDR1, which has been found in human colon carcinoma cell lines, and MDR1 is inducible by several herbal medicinal products and food supplements in human cancer cell lines (Brandin et al., 2007); therefore, it probably prevents the absorption of xenobiotics, enhances the excretion of xenobiotics, or both. However, the high expression of Mdr1a mRNA in colon may also contribute to colon cancer cell resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Many cancer chemotherapeutic drugs are Mdr1/MDR1 substrates. This was demonstrated by genetically engineered mice without the Mdr1 genes. For example, Mdr1a-null mice excrete less vinblastine, a cancer chemotherapeutic drug, into the intestinal lumen (van Asperen et al., 2000). MDR1 in humans seems to be highest in tumors originating from tissues that normally express high levels of MDR1, including colorectal epithelium. In human colon cancer, expression of MDR1 correlates with pathological grading of tumors, being most intense in well differentiated tumors and low in poorly differentiated tumors (Ho et al., 2003). Disruption of Mdr1a in mice markedly decreases the number of polyps and cancers in intestine (Mochida et al., 2003). Unsuccessful cancer chemotherapy due to Mdr/MDR1-dependent drug resistance calls for a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of Mdr/MDR1. It has been shown that α-naphthyl isothiocyanate can inhibit MDR1-mediated excretion of anticancer drugs in human cancer cell lines (Hu and Morris, 2004). Therefore, intestinal MDR1 may be a potential target for chemosensitizing drugs in treating colon cancer.

The Mdr1b transporter, which has similar functions as Mdr1a, has a very different tissue distribution pattern in mice (Fig. 1). Mdr1b mRNA is most abundantly expressed in ovary and placenta, which indicates it probably has a more important protective role against xenobiotics in females. It has been shown that several sex hormones are substrates for human MDR1 in vitro (Ueda et al., 1992). The highly expressed Mdr1b in mouse ovary may protect the tissue against excessive hormone accumulation. Placental Mdr1b is considered a protective mechanism against xenobiotic insults to the fetus (Behravan and Piquette-Miller, 2007). The expression of both Mdr1a and 1b mRNA is low in liver compared with the GI tract, indicating that the hepatic excretion of xenobiotics into bile canaliculi is probably more dependent on other apical efflux transporters.

The Mdr2 transporter is unique, because it is a phospholipid flipase rather than a xenobiotic transporter. It is predominantly expressed in liver, and it transfers phospholipid from the inner to outer canalicular membrane to protect the biliary tree from bile acids as well as forming bile acid-cholesterol-phospholipid micelles, to keep cholesterol from precipitating in the biliary tree, and to promote lipid absorption from the intestine. The protective role of Mdr2 was demonstrated in mice with homozygous disruption of the Mdr2 gene, which developed progressive inflammatory cholangitis and hepatocarcinogenesis (Mauad et al., 1994). However, mice heterozygous for the Mdr2 gene have diminished steatohepatitis on a methionine-choline-deficient diet (Igolnikov and Green, 2006). Therefore, how Mdr2 contributes to liver diseases in mice remains elusive. The human ortholog of mouse Mdr2 is MDR3, and genetic deficiency in this human transporter results in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (Maisonnette et al., 2005) and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Dixon et al., 2000).

Gender-divergent expression of efflux transporters indicates different capabilities of drug excretion between males and females. Conversely, it was shown in this laboratory that the xenobiotics uptake transporters, organic anion-transporting polypeptides 1a1 and 3a1, are male-predominant (Cheng et al., 2006). This suggests that female mice may accumulate less of the drug in liver than male mice.

The female-predominant pattern of Mdr1a and 1b expression is due to the repression by androgens in mouse kidneys (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, exogenous estrogen also decreased Mdr1a and 1b mRNA expression in male kidneys. It has been demonstrated that P-glycoprotein levels are inducible by several types of female sex hormones (estrone, estriol, and ethynyl estradiol) in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (Kim and Benet, 2004). The difference between the previous studies and the present finding could be due to different models and study approaches. First, it should be remembered that a cell line often does not replicate the in vivo situation. Second, administration of exogenous estradiol may activate other nuclear receptors in an estrogen-independent way, which may exert inhibitory effects on the expression of Mdr1s.

Adult brain is a privileged site due to protection by the blood-brain barrier. The expression of Mdr1a and 1b on the blood-brain barrier is important in protecting against xenobiotic insults, by decreasing the penetration of drugs into brain. It has been shown that Mdr1a-null mice have higher brain concentrations of ivermectin, vinblastine, digoxin, and cyclosporine A after their administration (Schinkel et al., 1994). Disruption of both Mdr1a and 1b in mice results in enhanced penetration of steroid hormones, such as corticosterone, cortisol, aldosterone, and progesterone into brain (Uhr et al., 2002). The expression of both Mdr1a and 1b mRNA is low in the pre- and neonatal brain and other organs. The low expression of Mdr1s in brain correlates with the high vulnerability to xenobiotics in newborns, which results in a challenge in treating newborn diseases without significant side effects to the brain. In contrast, the expression of Mdr2 in liver was high at birth, which even exceeded adult levels. Mdr2 pumps phospholipids into bile, which subsequently aids in digestion and absorption of lipophilic compounds. Therefore, enhanced expressed of Mdr2 at birth may benefit the newborns in nutrient acquisition, including fat from milk, and lipophilic vitamins (A, D, E, and K) that are essential for development. Neonatal up-regulation of the mRNAs of several nuclear receptors in liver was observed, including CAR, PXR, FXR, PPARα, and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α, by the present laboratory (data not shown). Within 10 kilobases of the promoter region of Mdr2, apparent binding sites for PXR, FXR, CAR, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α, and PPARα have been identified (NHRscan software; Sandelin and Wasserman, 2004). It is possible that some of these nuclear receptors may mediate the expression of Mdr2 during development. Our preliminary data indicate that the induction of Mdr2 in newborns is abolished in FXR-null mice, indicating the neonatal surge of Mdr2 is FXR-dependent.

The microsomal enzyme inducers used in the present study are common chemicals found in the environment or as pharmaceutical drugs. For example, TCDD is found in burnt trash; phenobarbital is used for treating seizures; and ethoxyquin, a quinoline-based antioxidant, is used as a food preservative. These chemicals at the dosages used in this study were found to up-regulate cytochrome P450 enzymes in rats and mice (Hartley and Klaassen, 2000; Cheng et al., 2005). However, the present study indicates that only a few chemicals induce Mdr transporters. It has been demonstrated that dosing rats with PXR agonists PCN and dexamethazone both increased P-glycoprotein protein expression in liver plasma membranes and in brain capillaries (Bauer et al., 2004). In the present study, PCN administration increased Mdr1a and 1b mRNA expression in rat brain, but it did not alter the expression of any of the three Mdrs in liver. These different observations on the chemical induction of Mdrs could be due to differences in species (rats versus mice), doses (the present study used higher doses of PCN and dexamethazone than the previous study), or detection methods (the present study detected mRNA, whereas the previous study detected protein, and the increase in Mdr protein but not mRNA might indicate post-transcriptional modifications of Mdrs). In addition, it should be noted that dexamethazone is also a potent ligand for the glucocorticoid receptor. Therefore, the induction of Mdr2 by dexamethazone in liver could also involve activation of PXR-independent pathways. Down-regulation of liver Mdr2 occurred in mice treated with PB and DAS. It has been shown that CLFB in the diet induces mouse Mdr2 (Chianale et al., 1996). This was not observed in the present study, which may due to strain differences, or to route of administration.

In conclusion, the present study examined the tissue distribution of Mdrs mRNA in mouse and reveals gender-divergent expression of Mdrs, demonstrates the effect of hormones on their expression, determines the ontogenic expression patterns of Mdr mRNAs, and tests the inducibility of Mdrs by microsomal enzyme inducers.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the Ph.D. students and postdoctoral students in C.D.K.'s laboratory.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [Grants ES-09649, ES-09716, and RR021940].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://dmd.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/dmd.108.023721.

ABBREVIATIONS: Mdr, multidrug resistance; GI, gastrointestinal; GH, growth hormone; MEI, microsomal enzyme inducer; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; CAR, constitutive androstane receptor; PXR, pregnane X receptor; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; PCB126, polychlorinated biphenyl 126; lit-lit, growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor-deficiency; DHT, 5α-dihydroxytestosterone; E2, 11β-estradiol; GHRH, growth hormone-releasing hormone; BNF, β-naphthoflavone; PB, phenobarbital; TCPOBOP, 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene; DAS, diallyl sulfide; PCN, pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile; SPR, spironolactone; CLFB, clofibric acid; CPFB, ciprofibrate; DEHP, diethylhexylphthalate; BHA, butylated hydroxyanisole; OPZ, oltipraz; bDNA, branched DNA; ANOVA, analysis of variance; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; FPGH, female-patterned growth hormone; GNX, gonadectomy; HX, hypophysectomy; MPGH, male-patterned growth hormone.

References

- Bauer B, Hartz AM, Fricker G, and Miller DS (2004) Pregnane X receptor up-regulation of P-glycoprotein expression and transport function at the blood-brain barrier. Mol Pharmacol 66 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behravan J and Piquette-Miller M (2007) Drug transport across the placenta, role of the ABC drug efflux transporters. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 3 819–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley G, Juranka PF, and Ling V (1988) Mechanism of multidrug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta 948 87–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady JM, Cherrington NJ, Hartley DP, Buist SC, Li N, and Klaassen CD (2002) Tissue distribution and chemical induction of multiple drug resistance genes in rats. Drug Metab Dispos 30 838–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandin H, Viitanen E, Myrberg O, and Arvidsson AK (2007) Effects of herbal medicinal products and food supplements on induction of CYP1A2, CYP3A4 and MDR1 in the human colon carcinoma cell line LS180. Phytother Res 21 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschman E, Arceci RJ, Croop JM, Che M, Arias IM, Housman DE, and Gros P (1992) mdr2 encodes P-glycoprotein expressed in the bile canalicular membrane as determined by isoform-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem 267 18093–18099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X and Klaassen CD (2006) Regulation of mRNA expression of xenobiotic transporters by the pregnane x receptor in mouse liver, kidney, and intestine. Drug Metab Dispos 34 1863–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Maher J, Dieter MZ, and Klaassen CD (2005) Regulation of mouse organic anion-transporting polypeptides (Oatps) in liver by prototypical microsomal enzyme inducers that activate distinct transcription factor pathways. Drug Metab Dispos 33 1276–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Maher J, Lu H, and Klaassen CD (2006) Endocrine regulation of gender-divergent mouse organic anion-transporting polypeptide (Oatp) expression. Mol Pharmacol 70 1291–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chianale J, Vollrath V, Wielandt AM, Amigo L, Rigotti A, Nervi F, Gonzalez S, Andrade L, Pizarro M, and Accatino L (1996) Fibrates induce mdr2 gene expression and biliary phospholipid secretion in the mouse. Biochem J 314 781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon PH, Weerasekera N, Linton KJ, Donaldson O, Chambers J, Egginton E, Weaver J, Nelson-Piercy C, de Swiet M, Warnes G, et al. (2000) Heterozygous MDR3 missense mutation associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: evidence for a defect in protein trafficking. Hum Mol Genet 9 1209–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley DP and Klaassen CD (2000) Detection of chemical-induced differential expression of rat hepatic cytochrome P450 mRNA transcripts using branched DNA signal amplification technology. Drug Metab Dispos 28 608–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho GT, Moodie FM, and Satsangi J (2003) Multidrug resistance 1 gene (P-glycoprotein 170): an important determinant in gastrointestinal disease? Gut 52 759–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K and Morris ME (2004) Effects of benzyl-, phenethyl-, and alpha-naphthyl isothiocyanates on P-glycoprotein- and MRP1-mediated transport. J Pharm Sci 93 1901–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HC, Nguyen T, and Pickett CB (2000) Regulation of the antioxidant response element by protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of NF-E2-related factor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 12475–12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igolnikov AC and Green RM (2006) Mice heterozygous for the Mdr2 gene demonstrate decreased PEMT activity and diminished steatohepatitis on the MCD diet. J Hepatol 44 586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY and Benet LZ (2004) P-glycoprotein (P-gp/MDR1)-mediated efflux of sex-steroid hormones and modulation of P-gp expression in vitro. Pharmacol Res 21 1284–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher JM, Slitt AL, Cherrington NJ, Cheng X, and Klaassen CD (2005) Tissue distribution and hepatic and renal ontogeny of the multidrug resistance-associated protein (Mrp) family in mice. Drug Metab Dispos 33 947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonnette F, Abita T, Barriere E, Pichon N, Vincensini JF, and Descottes B (2005) The MDR3 gene mutation: a rare cause of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC). Ann Chir 130 581–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauad TH, van Nieuwkerk CM, Dingemans KP, Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, Notenboom RG, van den Bergh Weerman MA, Verkruisen RP, Groen AK, and Oude Elferink RP (1994) Mice with homozygous disruption of the mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene. A novel animal model for studies of nonsuppurative inflammatory cholangitis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Am J Pathol 145 1237–1245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida Y, Taguchi K, Taniguchi S, Tsuneyoshi M, Kuwano H, Tsuzuki T, Kuwano M, and Wada M (2003) The role of P-glycoprotein in intestinal tumorigenesis: disruption of mdr1a suppresses polyp formation in Apc(Min/+) mice. Carcinogenesis 24 1219–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A and Wasserman WW (2004) Prediction of nuclear hormone receptor response elements. Mol Endocrinol 19 565–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel AH, Smit JJ, van Tellingen O, Beijnen JH, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Mol CA, van der Valk MA, Robanus-Maandag EC, and te Riele HP (1994) Disruption of the mouse mdr1a P-glycoprotein gene leads to a deficiency in the blood-brain barrier and to increased sensitivity to drugs. Cell 77 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, Oude Elferink RP, Groen AK, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Mol CA, Ottenhoff R, van der Lugt NM, and van Roon MA (1993) Homozygous disruption of the murine mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene leads to a complete absence of phospholipid from bile and to liver disease. Cell 75 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi T, Nakura H, Asoh M, Watanabe M, Tanaka M, Kumai T, Takashima S, Imaoka S, Funae Y, Yabusaki Y, et al. (1997) A comparison of hepatic cytochrome P450 protein expression between infancy and postinfancy. Life Sci 61 2567–2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebaut F, Tsuruo T, Hamada H, Gottesman MM, Pastan I, and Willingham MC (1987) Cellular localization of the multidrug-resistance gene product P-glycoprotein in normal human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84 7735–7738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Okamura N, Hirai M, Tanigawara Y, Saeki T, Kioka N, Komano T, and Hori R (1992) Human P-glycoprotein transports cortisol, aldosterone, and dexamethasone, but not progesterone. J Biol Chem 267 24248–24252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhr M, Holsboer F, and Müller MB (2002) Penetration of endogenous steroid hormones corticosterone, cortisol, aldosterone and progesterone into the brain is enhanced in mice deficient for both mdr1a and mdr1b P-glycoproteins. J Neuroendocrinol 14 753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Asperen J, van Tellingen O, and Beijnen JH (2000) The role of mdr1a P-glycoprotein in the biliary and intestinal secretion of doxorubicin and vinblastine in mice. Drug Metab Dispos 28 264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XJ, Hayes JD, and Wolf CR (2006) Generation of a stable antioxidant response element-driven reporter gene cell line and its use to show redox-dependent activation of nrf2 by cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Res 66 10983–10994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]