Abstract

Objective

To describe the foci, activities, methods, and results of a four-year research project identifying the unintended consequences of computerized provider order entry (CPOE).

Methods

Using a mixed methods approach, we identified and categorized into nine types 380 examples of the unintended consequences of CPOE gleaned from fieldwork data and a conference of experts. We then conducted a national survey in the U.S.A. to discover how hospitals with varying levels of infusion, a measure of CPOE sophistication, recognize and deal with unintended consequences. The research team, with assistance from experts, identified strategies for managing the nine types of unintended adverse consequences and developed and disseminated tools for CPOE implementers to help in addressing these consequences.

Results

Hospitals reported that levels of infusion are quite high and that these types of unintended consequences are common. Strategies for avoiding or managing the unintended consequences are similar to best practices for CPOE success published in the literature.

Conclusion

Development of a taxonomy of types of unintended adverse consequences of CPOE using qualitative methods allowed us to craft a national survey and discover how widespread these consequences are. Using mixed methods, we were able to structure an approach for addressing the skillful management of unintended consequences as well.

Keywords: Attitude to computers, Hospital information systems, User-computer interface, Physician order entry

1. Introduction

When our study began in October of 2003, the unintended consequences of CPOE were a little-discussed area. Patterson et al. had identified and described what they called “side effects” of a different, but similar, kind of system, bar code medication administration (BCMA) [1]. They used a relatively structured ethnographic approach to studying BCMA in Veterans Administration hospitals and identified side effects which they believed could lead to adverse drug events (ADEs). BCMA is supposed to prevent ADEs, but there are numerous unintended consequences they documented that could lead to mistakes. They offered suggestions about how to “eliminate these side effects before they contribute to adverse outcomes” [1, p. 540].

Problems related to clinical decision support had likewise been described in the literature. Although decision support is often cited as a reason for implementing CPOE, there has been controversy about the appropriate number of alerts and reminders, since too many tend to overwhelm and annoy users [2]. One 1989 report described an experiment where, to reduce the time between alert posting and review by the clinician, a flashing light mechanism was placed on top of the computer and designed to flash to let a user know when an alert was present. The system was extremely effective in encouraging a rapid response to the alert, reducing the average acknowledgment time from 28 hours to .1 hour, but users insisted the experiment be halted because the lights were too annoying [3]. This is a dramatic example of a negative unintended consequence of an otherwise effective system.

Medical error reduction is a prime reason for implementing CPOE, but users are also concerned that new kinds of errors are being made because of clinical systems. Many papers written about CPOE gave brief mention to this concern or cited anecdotes, but there were no published studies about mistakes that could be caused by CPOE. The Physician Order Entry Team (POET), a group of researchers based at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, U.S.A., was conducting a study of success factors for implementing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), defined as direct entry of orders into the computer by physicians or others with the same ordering privileges, when we began noticing unintended consequences (UCs) that might lead to errors. The clearest example is entry of an order for the wrong patient because of what we call a “juxtaposition error” when an item near the one actually desired is clicked by mistake.

Colleagues doing similar qualitative studies in Australia and The Netherlands were discovering these UCs as well, and a collaborative effort in 2002 produced a general description of kinds of adverse consequences caused by clinical information systems (CIS) [4]. This was a rather startling revelation at a time when CPOE was being touted as the “leap” that hospitals should take in the interest of patient safety [5] and little attention was being paid to problems caused by CPOE. In three separate observational studies, these research teams had continually witnessed “wrong patient” juxtaposition errors. Similar errors occur when one clicks on a test or medication listed on the screen next to the one needed. The summary paper by Ash, Berg, and Coiera highlighted the phrase “unintended consequences of CPOE,” which has become widely accepted and used [4]. This paper was influenced by several monographs that dramatically describe the unintended consequences of technology in general [6–9]. Since publication of the Ash, Berg, Coiera paper [4], numerous papers in both medical and the medical informatics journals have further described the unintended consequences of health information technology [10–18].

With funding from the U.S. National Library of Medicine, POET has been able to conduct an in-depth study over the past four years utilizing both qualitative and quantitative methods to discover more about these UCs of CPOE. Data were gathered via two expert panel conferences, fieldwork at a total of six sites (one outpatient and five primarily inpatient), and a national telephone survey of all CPOE sites in the U.S. The aims were to identify types of UCs and strategies for preventing, managing or overcoming them, and to provide tools to help implementers address them. The following presents a summary of the research foci, methods, and results, along with general conclusions about the overall project.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample selection

The main criterion for site selection for fieldwork was that organizations have a reputation for excellence in using clinical information systems. Excellent organizations learn from their mistakes [19–20] and therefore staff members in those organizations have analyzed the issues and are knowledgeable about strategies for overcoming obstacles. We were seeking sites with personnel who would be willing to 1) describe surprises they have experienced and managed, and 2) be observed during the order entry process. Sites represented a geographic distribution, different types (e.g. teaching and community hospitals) and ownership (e.g., public and private), varying durations of experience with CPOE, and both commercially and locally developed systems. Kaiser Permanente Northwest in Oregon, selected for excellence in outpatient CPOE, uses EpicCare (Epic Systems, Madison, WI), and is a health maintenance organization. Other sites included: Wishard Memorial Hospital, a county hospital in Indianapolis, IN using the locally developed Regenstrief system; The Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA, which uses a locally developed system; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, which uses a newer version of the Brigham system; Faulkner Hospital, a community hospital in Boston, MA, that uses the commercial MediTech system (Westwood, MA); and Alamance Regional Hospital in Burlington, NC, which uses the Eclipsys commercial system (Boca Raton, FL). We received human subjects approval from each site and from the researchers’ organizations. Within each site, informants for interviews were selected based on their knowledge of what had occurred during CPOE implementation and use and their representative roles (physician, nurse, pharmacist, implementer, champion, skeptic, etc.). We observed clinicians entering orders in all areas of the hospitals and clinics. Experts for the expert conferences were selected based on hands-on experience with CPOE implementation and included clinician implementers from a variety of hospital types and vendor organizations.

2.2. Data Collection

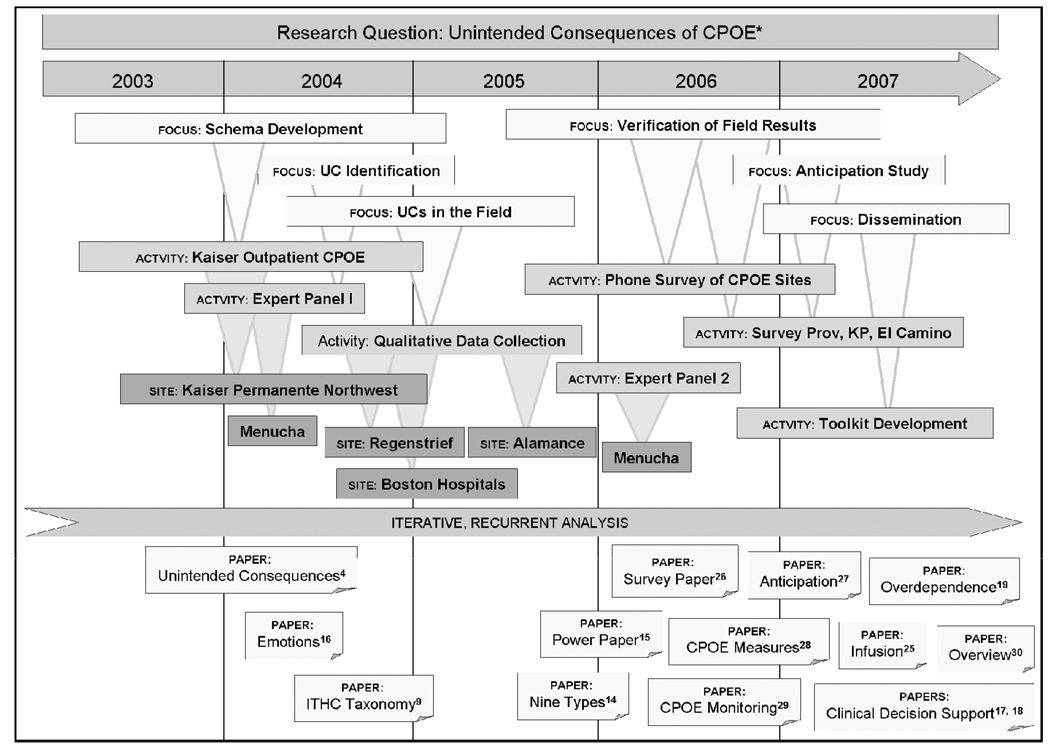

Figure 1 illustrates the progression of data gathering, analysis, and reporting of results that occurred between 2003 and 2007, starting with a transition period at Kaiser Permanente Northwest between the success factors study and the current UC study. We gathered data at Kaiser on an ongoing basis between the spring of 2003 and winter of 2004, developing refined semi-structured interview and observational techniques during the transition to studying UCs. During that period, we conducted 29 hours of observation in four clinics, shadowing 15 clinicians, and we interviewed 12 clinicians and staff members. In the spring of 2004 we held a conference of invited experts at the Menucha retreat center near Portland, OR to gather stories about UCs from the experts and to gain guidance about questions to ask and what to look for in the field. We then spent three to four days at each of our five inpatient study sites with four to six investigators on site at any one time. We conducted 390 hours of observation with 95 clinicians and did 32 interviews. Observations were documented with extensive field notes. Taped oral history interviews probed the history of surprises that occurred over time at each site. Realizing that it is hard to know when consequences are indeed unintended, we developed a short survey instrument to assess what clinicians being impacted by CPOE expect, and administered it to groups at three sites. Once we had identified the major types of UCs, we developed, piloted, and administered a telephone survey instrument designed to elicit information about the nature of UCs from all U.S. hospitals reporting that they have CPOE and to identify infusion, or levels of sophistication, of CPOE implementation efforts. A second conference of experts was held in May of 2006 to help interpret our results and to plan dissemination strategies, including publication of a set of tools that implementers could use for identifying, managing, and overcoming UCs in their hospitals.

Figure 1.

POET Research Overview 2003–2007

*Foci, activities, and sites as they were approached over time. Across the top are the years during which the work took place. FOCUS indicates the objective of activities during that time period. ACTIVITY indicates expert panels, surveys, and development of tools. SITE shows places where data gathering took place. PAPER indicates publications that emanated from the activities. Full citations to these publications are included in the References section of this paper.

2.3. Data Analysis

We first reviewed data gathered at Kaiser [21] during the transitional period between projects to gain an overview of UCs and developed a general schema that included positive as well as negative UCs [22]. Data collected during the expert conference and at the remaining five field sites yielded 750 pages of field notes and transcripts. The POET team reached consensus on each description of what seemed to be a UC, approximately 80 from the Menucha conference and 300 from fieldwork. As we analyzed them in detail, we realized that the initial UC schema we had developed [22] was too broad and superficial and that we would need to develop a more sophisticated taxonomy. Using a card sort method [23] and grounded theory approach [24], we iteratively developed a taxonomy of nine major types of adverse UCs into which all 380 instances fit, thus reaching saturation [25, p. 520]. Using an axial coding approach [26], we then explored each type in depth, discovering subcategories within each of the nine major categories. We developed survey questions based on what we had learned in the field and administered a telephone survey aimed at all CPOE sites in the U.S.A. We held another Menucha conference of experts to verify that these results made sense to the experts and to plan dissemination of tools to help implementers address each kind of UC. Finally, we developed each of the recommended tools with further guidance from the experts, using the Delphi technique and tree mapping.

3. Results

3.1 The initial schema

The initial broad schema of consequences related to CPOE included categories of intended and unintended consequences, desirable and undesirable, direct and indirect, and “two sided” consequences that could be either desirable or undesirable depending on one’s point of view [22]. This schema provided a valuable framework for fieldwork because it assured that we would not limit our foci to adverse consequences. While most informaticians are interested in undesirable consequences because they need careful management, it is also heartening to know that serendipitous, beneficial surprises occur as well.

3.2 The nine types of unintended adverse consequences related to CPOE

Using the card sort method, we developed a “short list” of nine categories based on the larger list. The categories were validated as we analyzed the full complement of UCs. We have published a paper summarizing overall results [27], as well as specific papers about changes in the power structure resulting from CPOE [28], emotions related to CPOE [29]; the unintended consequences of CDS [30–31]; and overdependence on the technology [32]. As we conducted our analysis, we discovered that a large number of consequences, over 20% of the total, emanated from issues with clinical decision support (CDS). Briefly, the nine categories, in descending order of frequency, are:

More / New Work Issues

Physicians find that CPOE adds to their workload by forcing them to enter required information, respond to alerts, deal with multiple passwords, and expend extra time.

Workflow Issues

Many UCs result from mismatches between the CIS and workflow and include workflow process issues, workflow and policy/procedure issues, workflow and human computer interaction issues, workflow and clinical personnel issues, and workflow and situation awareness issues.

Never Ending Demands

Because CPOE requires hardware technically advanced enough to support the clinical software, there is a continuous need for new hardware, more space in which to put this hardware, and more space on the screen to display information. In addition, maintenance of the knowledge base for decision support and training demands are ongoing.

Paper Persistence

It has long been hoped that CIS will reduce the amount of paper used to communicate and store information, but we found that this is not necessarily the case since it is useful as a temporary display interface.

Communication Issues

The CIS changes communication patterns among care providers and departments, creating an “illusion of communication,” meaning that people think that just because the information went into the computer the right person will see it and act on it appropriately [33].

Emotions

As outlined in the paper by Sittig et al. [29], these systems cause intense emotions in users. Unfortunately, many of these emotions are negative and often result in reduced efficacy of system use, at least in the beginning.

New Kinds of Errors

As noted by Koppel et al. [11] and Ash et al. [4], CPOE tends to generate new kinds of errors such as juxtaposition errors, in which clinicians click on the adjacent patient name or medication from a list and inadvertently enter the wrong order.

Changes in the Power Structure

The presence of a system that enforces specific clinical practices through mandatory data entry fields changes the power structure of organizations. Often the power or autonomy of physicians is reduced in an effort to standardize [34], while the power of the nursing staff, information technology specialists, and administration is increased [28].

Overdependence on Technology

As hospitals become more dependent on these systems, system failures can wreak havoc when paper backup systems are not readily available [32].

3.3. The national survey

We had already determined that the UC categories list was both useful and easy to understand and use, so we operationalized most of the categories by asking questions about UCs in a national survey. Those surveyed were to answer these questions as yes or no, and if yes, to rate the importance of this issue from 1 (not very important) to 5 (very important) (no = 0). The questions are shown in Table 1. We were also interested in discovering how sophisticated each CPOE implementation was, so we developed and piloted a set of questions about “infusion,” which is the depth or level of functionality and use of an innovation and it increases as an information system becomes more deeply embedded within an organization’s work processes [35–36]. Table 2 includes the infusion questions we asked each respondent during the interview survey. We surveyed the entire population of acute care hospitals listed in the 2004 HIMSS AnalyticsSM Database as having reported that they have CPOE in place (N = 448). Since that database did not include U.S. Veterans Affairs hospitals, which we feel are important models of CPOE use, we also surveyed VA hospitals (N = 113). We conducted interviews with staff at 176 hospitals, discovering that a large number listed as having CPOE did not in fact have functioning CPOE systems. We also found that a number of hospitals have policies against doing surveys.

Table 1.

Phone Survey Unintended Consequences Questions

| Workflow (process) |

| Question 1: We have noticed in our research that when CPOE systems are in use, this alters how people do their work. Have you seen this, how important is it, and could you comment? |

| Communications |

| Question 2: Communication is really important in clinical care. Have you seen any alterations in communication patterns because of CPOE, how important are these alterations, and could you comment? |

| Over-dependence on technology |

| Question 3: As we become more dependent on technology, we’ve noticed that people may have a hard time when the CPOE system is not available. If your computer went down, would this be an issue for your organization, how important would it be, and could you comment? |

| Power |

| Question 4: We have noticed the balance of power may shift when CPOE is used. Have you noticed that at your organization, how important is it, and could you comment? |

| More work, new work |

| Question 5: We think of computers as labor saving devices, but we all know that sometimes they’re not. Are there examples in your institution of new kinds of work that you didn’t do before, how important is this, and could you comment? |

| New kinds of errors |

| Question 6: CPOE has been proposed as a solution to patient safety issues, but may have created others. Have you seen new patient safety issues with CPOE, how important are they, and could you comment? |

| Never ending demands of technology |

| Question 7: The information system typically needs a great deal of support in terms of maintenance, training, updating order sets, etc. Has this been an issue in your organization, how important is it, and could you comment? |

| Emotions |

| Question 8: We have seen many emotional responses to the system. Have you seen users express strong feelings about CPOE, how important is this, and could you comment? |

Table 2.

Phone Survey Infusion Questions

| What percentage of all orders throughout the hospital is written by physicians using CPOE? Scale: under or over 50% |

| Which of the following types of orders do the physicians enter: medications, labs, radiology? Scale: additional points for each |

| Can you sign in once to get to all aspects of your clinical information system? Scale: yes or no |

| Do you have any decision support (e.g. order sets, drug-drug interactions, pop-up alerts) at the time of order entry? Scale: additional points for each |

| Do you have a CPOE system-related committee with physicians on it? Scale: yes or no |

| How many years has the CPOE system been in place? Scale: additional points for each year |

3.3.1 Infusion levels

In the 176 responding hospitals, we found the length of time that CPOE had been in place ranged from 6 months to 25 years (median = 5 years) while the percentage of orders entered electronically ranged from 1–100% (median = 90.5%). We found that greater than 96% of the sites used CPOE to enter pharmacy, laboratory and imaging orders and that 82% were able to access all aspects of their clinical information system with a single sign-on. Further, 86% of the respondents had access to order sets, drug-drug interaction warnings, and pop-up alerts even though nearly all hospitals surveyed were community hospitals with commercial systems. Finally, we found that 90% of the hospitals had a CPOE committee with a clinician representative in place [37].

3.3.2 Unintended consequences survey

The UC survey results verified the existence of these UCs, and analysis of comments offered insight into the nature of the consequences. All types of consequences are indeed widespread. Our informants did not consider two of them, power shifts and new kinds of errors, as important as the others, however. We verified that there are positive as well as negative unintended consequences, and often the same consequence can be viewed in different ways by different people, depending on their perspectives. We can only speculate about why power shifts and new kinds of errors were not considered as important as other types: those answering the questions were generally information technology professionals who may not realize that power is shifting in their direction. They may also believe that the new kinds of errors are not of a serious nature. A paper reporting more extensive results has been published [38].

3.4. The anticipation survey

To find out if the “unintended” or “unanticipated” consequences that we had identified were perhaps already known by others in the field and therefore actually anticipated during CPOE implementations, we designed and piloted an “anticipation survey.” It was designed to determine what end user clinicians were expecting to happen in organizations that were about to implement CPOE. The questions, which were asked in person, are shown in Table 3. The survey was administered as a short interview survey to 83 clinicians at three community hospitals at common gathering spots such as the cafeteria. Results from each hospital were fed back to the implementers at those individual sites. The research team conducted a comparative analysis across sites. Briefly, end users and others affected by CPOE were usually aware that CPOE was coming and that their workflow might be disrupted for a certain period of time, but they were optimistic that in the long run it would be of benefit. Other UCs were rarely mentioned. Results are summarized in a published paper [39].

Table 3.

Short Interview Survey About Anticipation of CPOE

| About you: | |

| • | What is your role in the organization? If clinician, continue. Have you heard about Computer-based Provider Order Entry being implemented here? |

| • | If no…This is a new system that would allow the physicians to enter their patient orders directly into he computer system. |

| • | Have you been trained on it, tested it, and/or actually used it? |

| • | What effect do you think it will have on you? |

| • | Do you have experience with the clinical information system now available?” |

| How do you think the new CPOE system might compare to the current paper system? Advantages? Disadvantages? | |

| About the organization: | |

| • | What effect do you think CPOE will have on other clinicians within the organization? |

| • | Do you think it will be more positive or negative? In what way? |

| • | What does this mean for patients? |

| • | Do you think it will be more positive or negative? In what way? |

| • | What effect will the system have on the hospital as a whole? |

| • | Do you think it will be more positive or negative? In what way? |

3.5. Affirmation and Dissemination

The results of our fieldwork and the survey were disseminated to the experts prior to the Menucha conference held on May 4 and 5 of 2006. The experts affirmed our categories of UCs and recommended that we develop and disseminate a number of tools to assist implementers in avoiding or managing unintended consequences. These included a best practices guide for implementation to help avoid UCs, a checkup tool to help hospitals assess how well they are managing UCs, and a dashboard tool of recommended metrics that can help hospitals track their progress.

To develop recommendations about best practices, we looked at each UC type and asked how it could be prevented or mitigated. Since the resulting list of prevention measures resembled our list of success factors identified in our first project, we then performed an extensive exercise whereby we mapped each UC type and sub-type to each of the 80 success factors, aiming to enhance the success factors list. The result was a series of interactive “tree maps” published on our Web site, www.cpoe.org, which help a user look at a UC type and learn how to manage it. The success factors originally described withstood this test well: they were minimally edited, indicating that as a list of best practices, they were confirmed.

We designed and tested a number of survey instruments that form a series of checkup tools. The instruments illustrated in Table 1–Table 3 should prove helpful to hospitals over time. In addition, we have developed recommended metrics that form a dashboard tool, starting with a long list of ideal measures and honing them to a shorter, more realistic list, with the help of our experts [40–41]. The final list shown in Table 4 includes eight measures which are 1) important to measure on a continuing basis, 2) relatively easy to measure, and 3) are well defined. All of these tools are freely available on the Web site and in publications.

Table 4.

Suggested Measures for the Monitoring and Evaluation of Inpatient CPOE Systems

| • | Percent system uptime |

| • | Mean response time |

| • | Percent of all orders entered |

| • | Order sets used |

| • | Percent of alerts that fire |

| • | Alerts ignored or overridden |

| • | System interface efficiency (percent successful transmissions to pharmacy, lab, etc.) |

| • | Percent orders entered as “miscellaneous” or as free text |

4. Discussion

In this team’s earlier research on success factors for implementing CPOE, we cast a wide net because little was known at that time about factors leading to success or lack thereof. A rigorous yet open-ended grounded theory [24] approach was deemed most appropriate. As research questions became more focused, however, our qualitative methods became more structured. To investigate UCs of CPOE, we started with a broad schema of types and iteratively refined the schema by consulting experts, interviewing, and observing in the field [42]. Once a taxonomy of types was defined, we were able to craft survey questions and administer a national telephone survey. Because such a large number of adverse UCs relate to CDS, our attention is becoming even more focused in that arena [30].

As the team and expert consultants developed tools for helping implementers avoid, manage, or overcome UCs, we realized that all of the success factors identified and published in the past [43] can actually serve as UC avoidance mechanisms.

5. Conclusion

While it is hard summarizing results of an intense four year study of UCs, we can draw some general conclusions about both methods and UCs. First, the selected methods served us well for this study. The more structured and rapid techniques such as the anticipation survey efficiently augmented other kinds of fieldwork. Second, development of a taxonomy of types and subtypes not only allowed us to craft survey questions, but was also useful in structuring an approach for addressing management of UCs. One key in prevention of UCs is to pay attention to success factors for implementing CPOE in the first place. Since so many UCs are related to CDS, it seems that a fruitful area for future research would be identification of success factors for implementation of CDS.

Summary points.

What was known before this study

CPOE with CDS can reap benefits for hospitals, but use is not widespread in the U.S.A.

Fear of the unintended consequences of CPOE may be discouraging acceptance

What this study adds

Deeper understanding of the unintended consequences of CPOE

Knowledge about the levels of sophistication of CPOE implementations

Strategies for avoiding or dealing with the unintended consequences of CPOE

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on a presentation given at MedInfo 2007. This work was supported by grant LM06942 and training grant ASMM10031 from the U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. The funding agency had no role in development of this paper and none of the authors has conflicts to declare. All authors contributed to data gathering, analysis, and writing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Based on a paper presented at MedInfo 2007

References

- 1.Patterson ES, Cook RI, Render ML. Improving patient safety by identifying side effects from introducing bar coding in medication administration. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(5):540–553. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Rittenberg E, Teich JM, Fiskio J, Ma'luf N, et al. A randomized trial of a computer-based intervention to reduce utilization of redundant laboratory tests. Am J Med. 1999;106(2):144–150. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradshaw KE, Gardner RM, Pryor TA. Development of a computerized laboratory alerting system. Comput Biomed Res. 1989;22(6):575–587. doi: 10.1016/0010-4809(89)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: The nature of patient care information system related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104–112. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Leapfrog Group. [accessed 11/21/06];Factsheet: Computer physician order entry. Available at http://www.leapfroggroup.org/for_hospitals/leapfrog_safety_practices/cpoe.

- 6.Tenner E. Why things bite back: Technology and the revenge of unintended consequences. New York: Random House, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doerner D. The Logic of Failure: Recognizing and Avoiding Error in Complex Situations. New York: Basic Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrow C. Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies. Princeton NJ: Princeton U. Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiles JR. Inviting Disaster: Lessons from the Edge of Technology. New York: HarperBusiness; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger RG, Kichak JP. Computerized physician order entry: helpful or harmful? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):100–103. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, Abaluck B, Localio AR, Kimmel SE, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1197–1203. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wears RL, Berg M. Computer technology and clinical work: still waiting for Godot. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1261–1263. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nebeker JR, Hoffman JM, Weir CR, Bennett CL, Hurdle JF. High rates of adverse drug events in a highly computerized hospital. Arch Int Med. 2005;165(10):1111–1116. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, Clark RS, Watson RS, Nguyen TC, Bayir H, Orr RA. Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1506–1512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachter RM. Expected and unanticipated consequences of the quality and information technology revolutions. JAMA. 2006;295(23):2780–2783. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aarts J, Ash J, Berg M. Extending the understanding of computerized physician order entry: Implications for professional collaboration, workflow and quality of care. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76 Suppl 1:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAlearney AS, Chisolm DJ, Schweikhart S, Medow MA, Kelleher K. The story behind the story: Physician skepticism about relying on clinical information technologies to reduce medical errors. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eslami S, de Keizer NF, Abu-Hanna A. The impact of computerized physician medication order entry in hospitalized patients—A systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senge PM. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Currency Doubleday; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stavri PZ, Ash JS. Does failure breed success: Narrative analysis of stories about computerized physician order entry. Int J Med Inform. 2003;72:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ash JS, Chin HL, Sittig DF, Dykstra RH. Ambulatory computerized physician order entry implementation. Proc AMIA. 2005:11–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra RH, Guappone K, Carpenter JD, Seshadri V. Categorizing the unintended sociotechnical consequences of computerized provider order entry. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76 Supp 1:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Natualistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. pp. 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2000. p. 520. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell EM, Sittig DF, Ash JS, Guappone KP, Dykstra RH. Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(5):547–556. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Campbell E, Guappone K, Dykstra R. An unintended consequence of CPOE implementation: Shifts in power, control, and autonomy. Proc AMIA. 2006:11–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sittig DF, Krall M, Kaalaas-Sittig J, Ash JS. Emotional aspects of computer-based provider order entry: a qualitative study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(5):561–567. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Campbell EM, Guappone KP, Dykstra RH. Some unintended consequences of clinical decision support systems. Proc AMIA. 2007:26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sittig DF, Ash JS, Campbell EM, Guappone KP, Dykstra RH. Understanding the unintended consequences surrounding clinical decision support systems. Hosp IT Europe. 2008;1(1):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell EM, Sittig DF, Guappone KP, Dykstra RH, Ash JS. Overdependence on technology: An unintended adverse consequence of computerized provider order entry. Proc AMIA. 2007:94–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dykstra R. Computerized physician order entry and communication: Reciprocal impacts. Proc AMIA. 2002:230–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amalberti R, Auroy Yves, Berwick D, Barach P. Five system barriers to achieving ultrasafe health care. Ann Int Med. 2005;142:756–764. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saga V, Zmud RW. The nature and determinants of IT acceptance, routinization, and infusion. Proceedings IFIP TC8 Working Conference on Diffusion, Transfer and Implementation of Information Technology. 1993:67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orlikowski WJ, Robey D. Information technology and the structuring of organizations. Inform Sys Research. 1991;2(2):143–169. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sittig DF, Guappone K, Campbell E, Dykstra RH, Ash JS. A survey of U.S.A. acute care hospitals’ computer-based provider order entry system infusion levels. Proc MedInfo. 2007;12(Pt 1):252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, Guappone K, Campbell E, Dykstra RH. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:415–423. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sittig DF, Ash JS, Guappone K, Campbell E, Dykstra R. Assessing the anticipated consequences of computer-based provider order entry at three community hospitals using an open-ended, semi-structured survey instrument. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sittig DF, Thomas SM, Campbell E, Kuperman GJ, Artreja A, Waitman LR, Nichol P, Leonard K, Stutman H, Ash JS. Consensus recommendations for basic monitoring and evaluation of in-patient computer-based provider order entry systems; Proceedings Conference on Information Technology and Communication in Health; Victoria, BC Canada. 2007. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sittig DF, Campbell E, Guappone K, Dykstra R, Ash JS. Recommendations for monitoring and evaluation of in-patient computer-based provider order entry systems: Results of a Delphi survey. Proc AMIA. 2007:671–675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra RD, Campbell E, Guappone K. Exploring the unintended consequences of computerized physician order entry. Proc MedInfo. 2007;12(Pt 1):198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ash JS, Stavri PZ, Kuperman GJ. A consensus statement on considerations for a successful CPOE implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(3):229–234. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]