Abstract

Under normal physiological conditions, estrogen is a coronary vasodilator, and this response involves production of NO from endothelial cells. In addition, estrogen also stimulates NO production in coronary artery smooth muscle (CASM); however, the molecular basis for this nongenomic effect of estrogen is unclear. The purpose of this study was to investigate a potential role for the 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) in estrogen-stimulated neuronal nitric-oxide synthase (nNOS) activity in coronary artery smooth muscle. 17β-Estradiol produced a concentration-dependent relaxation of endothelium-denuded porcine coronary arteries in vitro, and this response was attenuated by inhibiting Hsp90 function with 1 μM geldanamycin (GA) or 100 μg/ml radicicol (RAD). These inhibitors also prevented estrogen-stimulated NO production in human CASM cells and reversed the stimulatory effect of estrogen on calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels. These functional studies indicated a role for Hsp90 in coupling estrogen receptor activation to NOS stimulation in CASM. Furthermore, coimmunoprecipitation studies demonstrated that estrogen stimulates bimolecular interaction of immunoprecipitated nNOS with Hsp90 and that either GA or RAD could inhibit this association. Blocking estrogen receptors with ICI182780 (fulvestrant) also prevented this association. These findings indicate an essential role for Hsp90 in nongenomic estrogen signaling in CASM and further suggest that Hsp90 might represent a prospective therapeutic target to enhance estrogen-stimulated cardiovascular protection.

Acute estrogen treatment rapidly increases coronary blood flow in postmenopausal women (Reis et al., 1994) and also in men (Blumenthal et al., 1997). In vitro studies have established that estrogen relaxes coronary arteries by targeting both endothelial (Gilligan et al., 1994) and smooth muscle cells (Mügge et al., 1993; White et al., 1995). Acute responses of endothelial cells to estrogen are mediated by estrogen receptor (ER) α (Chen et al., 1999) and involve production of nitric oxide via stimulation of the PI3-kinase-Akt signaling pathway (Haynes et al., 2000). Although less is known regarding estrogen signaling in coronary smooth muscle (CASM), we have recently identified type 1 (n)NOS as the predominant isoform expressed in both porcine and human CASM (White et al., 2005; Han et al., 2007). Furthermore, we have demonstrated that ERα-PI3-kinase-Akt signaling mediates acute estrogen action on human coronary myocytes and porcine coronary arteries as well (Han et al., 2006, 2007). However, the mechanism(s) of how ERα activation leads to enhanced NOS activity is not completely understood. The hypothesis of the present study is that 90-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) plays an essential role in coupling ER activation to NOS activity in CASM and that estrogen promotes the association of Hsp90 with nNOS in these cells. Because Hsp90 levels decline with age (Smith et al., 2006), it is important to understand the role of Hsp90 in mediating the response of CASM to estrogen and other vasoactive factors.

Materials and Methods

Coronary Arteries. We obtained fresh porcine hearts from local abattoirs. The left anterior descending coronary artery was excised immediately and placed into ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer solution of the following composition: 122 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 15.5 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 11.5 mM glucose, pH 7.2. Arteries were kept on ice during transport to the laboratory.

Tension Studies. Arteries were placed under a dissecting microscope, and excess fat and connective tissue were removed in ice-cold buffer solution. Two to four 5-mm rings were obtained from each left anterior descending coronary artery and prepared for isometric contractile force recordings as described previously (White et al., 2005). To control for possible indirect effects of endothelium-derived vasoactive factors, the endothelium was removed physically by rubbing the intimal surface and tested by observing the absence of acetylcholine-induced relaxation of the initial, stabilizing contraction. Rings were mounted on two triangular tissue supports, with one support fixed to stationary glass rod, and the other attached to a force-displacement transducer. Isometric contractions or relaxations were recorded on a PC computer using MacLab software (ADInstruments, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO). The tissue bathing solution was the modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer described above. The solution was oxygenated continuously (95% O2, 5% CO2) and maintained at 37°C. Coronary ring preparations were equilibrated for 90 min under an optimal resting tension of 2.0 g, and fresh bath solution was added to the tissue chamber every 30 min to prevent accumulation of metabolic end products. After the initial equilibration, preparations were exposed to maximally effective concentrations of a contractile agonist [i.e., 10 μM prostaglandin (PG)F2α] to ensure stabilization of the muscles. Pharmacological inhibitors were allowed to equilibrate with the arteries for at least 30 min before measurement of a complete estrogen concentration-response relationship (1–1000 nM). One vessel was exposed only to the constrictor agent to control for potential fading of the contractile response. The effects of 17α-estradiol, an “inactive” estrogen, were determined to control for possible vehicle artifact. Steroid vehicle was usually 50 to 75% ethanol, and this stock was diluted to a concentration of no more than 0.1% in the vessel chamber. Geldanamycin (GA; 1 μM) or radicicol (RAD; 100 μg/ml) were used to inhibit Hsp90. Nω-Nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 100 μM) was used to inhibit NOS activity. ICI182,780 (100 μM) is a nonselective ER antagonist.

Cell Culture. Human coronary artery smooth muscle cells were purchased from Cambrex (East Rutherford, NJ) and were grown in phenol red-free smooth muscle growth medium with 5% fetal bovine serum as described previously (White et al., 2002). Steroid hormones and growth factors were removed from FBS by charcoal-stripping. Only short-term cultures (passage 3–5) were used in the patch-clamp studies. Because vascular smooth muscle cells may dedifferentiate and develop a secretory phenotype with long-term culture, we used only low-passaged cells (passages 3–5).

Patch-Clamp Studies. For cell-attached patch studies, the recording chamber contained the following solution: 140 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 30 mM glucose, pH 7.4 (22–25°C). Activity of single potassium channels was recorded (with pCLAMP 10; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) in cell-attached patches by filling the patch pipette (2–5 MΩ) with Ringer's solution: 110 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES. Voltage across the patch was controlled by clamping the cell at 0 mV with the high concentration extracellular potassium solution. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Average channel activity (expressed as number of channels × single-channel open probability; NPo) in patches with multiple BKCa channels was determined as described previously (White et al., 1995). NPo calculations were based on 10 to 15 s of continuous recording during periods of stable channel activity. Although channel activity was observed at a variety of membrane potentials, most single-channel data were analyzed at a potential of +40mV, where BKCa channel openings are easily distinguished from other channel species to permit more accurate statistical analysis (Han et al., 1999).

Immunoblotting. Expression of Hsp90 and nNOS was detected using specific antibodies (1:1000; BD Biosciences Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY) as described previously (White et al., 2005). Protein concentrations were determined by DC protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). ADP-Sepharose beads were used to affinity extract NOS proteins from lysates. Purified positive control protein (nNOS pituitary extracts) was purchased from BD Biosciences Transduction Laboratories. Proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels using a Mini Protean II gel kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Proteins were then transferred to Hybond ECL membrane (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK) using a Mini-Trans-Blot electrophoretic transfer cell (Bio-Rad) at 100 V for 1 h. Blots were blocked with 5% nonfat milk overnight at 4°C. The membrane was then rinsed with Tris-buffered saline Tween (polyoxyethylene 20 sorbitan monolaurate) three times for 15 min and two times for 5 min. Blots were then probed with primary antibodies (nNOS 1:1000; BD Biosciences Transduction Laboratories) in Tris-buffered saline Tween containing 1% nonfat milk protein for 1 h. After washing, the membrane was then incubated with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare). Immunoprecipitation was carried out according to previous descriptions (Harris et al., 2008). In brief, 10 μg of anti-nNOS or anti-Hsp90 antibody was added to 1 ml of cell lysates (0.8 mg of protein) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Protein A/G agarose was then added, and samples were incubated for an additional 4 h at 4°C. The agarose beads were then centrifuged and washed three times with tissue lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were then eluted from the beads by adding SDS-sample buffer and boiling for 5 min. The agarose beads were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatants were used for immunoblotting by using either anti-nNOS or anti-Hsp90 antibodies.

NO Fluorescence Studies. The cell-permeable form of the NO fluorescent indicator 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2 DA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used to detect NO production in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells as described previously (White et al., 2002). In brief, cells were loaded with 1 μM DAF-2 DA (diluted from a 5 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide; 45 min) and washed several times with Ringer's solution. After incubation, cells were washed with Krebs' solution and placed on the stage of a 510 NLO confocal laser microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Drugs were then added to the cells, and fluorescence was measured. Quantitative analysis of confocal images was under the control of PHYSIOLOGY software (Carl Zeiss Inc.).

Statistical Analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. Statistical significance between two groups was evaluated by Student's t test for paired data. Comparison between multiple groups was made by the one-way analysis of variance test. A probability of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

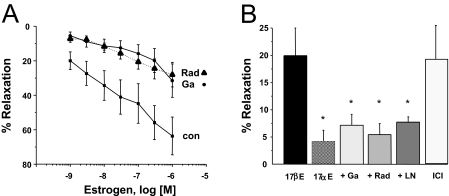

As illustrated in Fig. 1A, 17β-estradiol (E2) induces a concentration-dependent relaxation of endothelium-denuded porcine coronary arteries (precontracted with 10 μM PGF2α) in vitro. Estrogen produced significant relaxation of vessels over a physiological (nanomolar) range of concentrations. Maximal relaxation (measured at 1 μM) was 63.6 ± 10.9% (n = 9), with an EC50 value of 170 nM. In contrast, 17α-estradiol, a biologically less active steroid, had little effect on precontracted coronary arteries and produced a maximal relaxation of only 6.10 ± 3.18% at a concentration of 1 μM (n = 3). The relaxation effect of estrogen was attenuated significantly at all concentrations by either GA or RAD, both of which are inhibitors of Hsp90. For example, as illustrated in Fig. 1B, the relaxant effect of 1 nM 17β-estradiol was inhibited 65% by 1 μM GA(n = 5; P < 0.05) and 73% by 100 μg/ml RAD (n = 7; P < 0.02). At 1 μM 17β-estradiol, inhibiting Hsp90 with these agents reduced maximal relaxation by 56 and 51%, respectively (P < 0.03). Neither GA nor RAD affected precontracted arteries in the absence of estrogen. In addition, treating precontracted arteries with 10 nM ICI182,780, an estrogen receptor antagonist, induced a relaxation of 19.2 ± 7.3% (n = 7).

Fig. 1.

Estrogen-induced coronary artery relaxation involves Hsp90 and NO. A, mean concentration-response relationship for 17β-estradiol-induced relaxation of endothelium-denuded coronary arteries (con; n = 9) precontracted with 10 μM PGF2α. Another mean concentration-response relationship was measured for 17β-estradiol after pretreatment (30 min) with either 1 μM GA(n = 5) or 100 μg/ml RAD (n = 7). Each point represents the mean value ± S.E.M. B, mean relaxation response to 1 nM 17β-estradiol (17βE) in the absence or presence of 1 μM GA, 100 μg/ml RAD, or 100 μM l-NAME (LN). In addition, a complete concentration-response relationship for 17α-estradiol or ICI182,780 was also measured in PGF2α-contracted arteries, and the mean relaxation induced by either 1 μM 17α-estradiol (17αE; n = 3) or 10 nM ICI182,780 (ICI; n = 7) was measured in the absence of 17β-estradiol. Each points represents the mean value ± S.E.M. *, P < 0.05 compared with control (17βE).

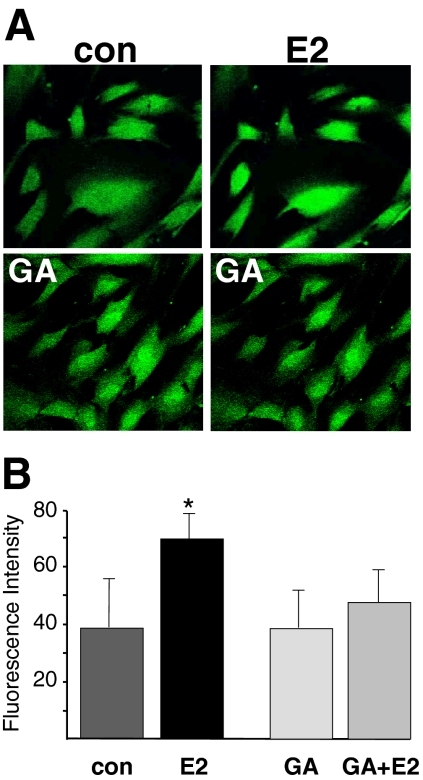

The relaxation response to estrogen was also attenuated significantly by l-NAME (100 μM; Fig. 1B). On average, l-NAME inhibited relaxation induced by 1 nM 17β-estradiol by 61% (n = 4; P < 0.02). As illustrated in Fig. 2A, 100 nM 17β-estradiol enhanced NO fluorescence compared with control levels. Average densitometry readings indicated that 10 nM 17β-estradiol nearly doubled NO fluorescence (density increased from 38.3 ± 16.7 to 69.0 ± 11.4; n = 4; P < 0.05) compared with control conditions. In contrast, pretreating cells with 1 μM GA (10 min) prevented estrogen from enhancing NO production (n = 4; Fig. 2B) in coronary myocytes.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of Hsp90 prevents estrogen-stimulated NO production in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. A, representative images of DAF-2 DA (1 μM)-loaded CASM cells before and 30 min after treatment with 100 nM 17β-estradiol (E2). Top, control cells before and after E2 treatment. Bottom, cells were pretreated with 1 μM GA (30 min), and images were then obtained as described in above. B, mean intensity (arbitrary units) of estrogen-stimulated DAF-2 fluorescence. Each bar represents mean ± S.E.M. fluorescence intensity of experiments (n = 4) illustrated in A. *, P < 0.05 compared with control fluorescence. con, control.

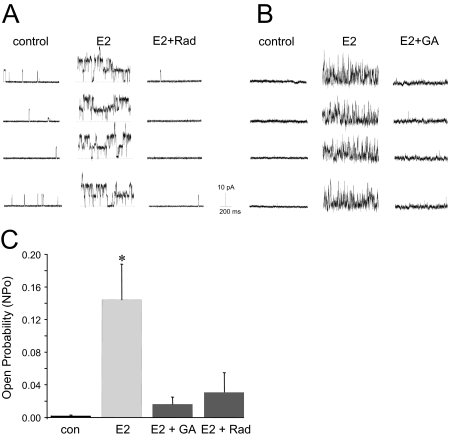

As illustrated in Fig. 3, cell-attached patch-clamp experiments reveal that either RAD or GA reversed estrogen-stimulated BKCa channel activity in single coronary myocytes. We (White et al., 1995, 2002; Darkow et al., 1997; Han et al., 1999) and others (Gollasch et al., 1996; Marijic and Toro, 2001) have characterized this high-conductance (200–250 pS) ion channel extensively in porcine and human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Single-channel patch-clamp experiments demonstrated that 100 nM 17β-estradiol increased BKCa channel activity (NPo) dramatically (from 0.0060 ± 0.0079 to 0.4037 ± 0.1474). It is noteworthy that addition of RAD (0.1 μg/ml) to the extracellular solution reduced estrogen-stimulated channel activity by ∼92% (NPo: 0.0317 ± 0.0401; n = 3; P < 0.007) (Fig. 3A). Although RAD was able to completely reverse the stimulatory effect of estrogen on BKCa channels, it had no effect on calcium-stimulated channel activity (data not shown). In addition, 1 μM GA produced a similar (∼89%) reversal of estrogen-stimulated BKCa channel activity (n = 7; P < 0.003) (Fig. 3B). A summary of the average effect of both GA and RAD on estrogen-stimulated BKCa channel activity is illustrated in Fig. 3C.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of Hsp90 reverses estrogen-stimulated BKCa channel activity in coronary artery myocytes. A, representative recordings of BKCa channel activity (+40 mV) from the same cell-attached patch before and 10 min after 100 nM E2, and then after subsequent treatment with 0.1 μg/ml RAD. Channel openings are upward deflections from the baseline (closed) state (dashed line). B, representative recordings of BKCa channel activity (+40 mV) from the same cell-attached patch before and 10 min after 100 nM E2 and then after subsequent treatment with 1 μM GA. C, summary of BKCa channel activity (NPo) in cell-attached patches. Each bar represents the mean channel NPo ± S.E.M. of each experimental condition. *, P < 0.003 compared with control (con) channel activity.

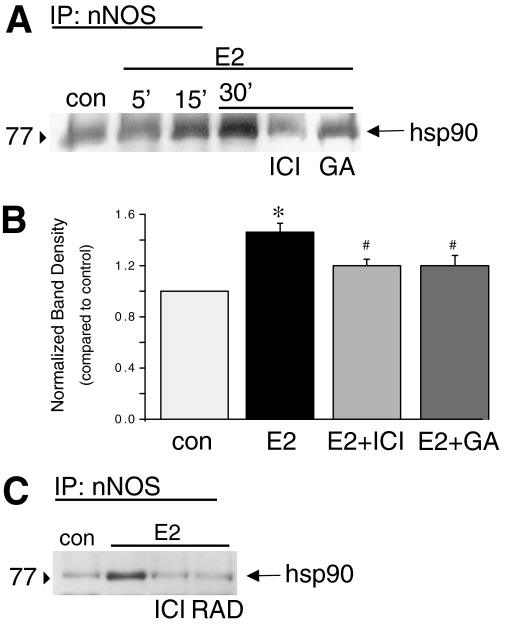

Association of Hsp90 with nNOS was measured in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells by immunoprecipitation of nNOS and subsequent immunoblotting with anti-Hsp90 antibody. Results illustrated in Fig. 4 reveal that 100 nM 17β-estradiol stimulates a time-dependent bimolecular interaction of Hsp90 with immunoprecipitated nNOS. On average, estrogen (30 min) enhanced Hsp90-nNOS association by 1.5 ± 0.07-fold over nonstimulated conditions (n = 4; P < 0.001). Furthermore, estrogen-stimulated Hsp90-nNOS interaction was attenuated significantly (P < 0.05) by either 100 nM ICI182780 (estrogen receptor antagonist; n = 4) or 1 μM GA(n = 4; Fig. 4, A and B). Similar results were obtained from immunoprecipitation of Hsp90 and subsequent immunoblotting with anti-nNOS antibody (data not shown). In addition, we found that inhibiting Hsp90 with RAD (0.1 μg/ml) also attenuated estrogen-stimulated Hsp90-nNOS association (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Estrogen stimulates association of Hsp90 with nNOS in CASM. A, representative blot illustrating interaction of nNOS immunoprecipitated from CASM lysate with Hsp90. Association of Hsp90 with nNOS was stimulated by 100 nM E2 (at 5, 15, and 30 min). Estrogen-stimulated protein interaction was inhibited by either 100 nM ICI182780 or 1 μM GA. Lines above the blot indicate experimental conditions. B, summary densitometry readings of coimmunoprecipitation experiments (30-min estrogen treatment). Each bar represents the mean ± S.E.M. of four experiments. *, P < 0.001 compared with control (con); #, P < 0.05 compared with E2 alone. C, representative blot illustrating interaction of nNOS immunoprecipitated from CASM lysate with Hsp90. Association of Hsp90 with nNOS was stimulated by 100 nM E2 (30 min). Estrogen-stimulated protein interaction was inhibited by either 100 nM ICI182780 (ICI) or 0.1 μg/ml RAD. Lines above the blot indicate experimental conditions.

Discussion

Despite the demonstrated ability of smooth muscle-derived NO to mediate acute estrogen relaxation of coronary arteries (Mügge et al., 1993; Darkow et al., 1997; White et al., 2002), the mechanisms coupling ER activation to NOS activity in this tissue are not well understood. Molecular chaperones, such as Hsp90, help to stabilize cellular proteins and maintain their ability to serve as signaling molecules. Our studies indicate an important role for Hsp90 in estrogen signal transduction in CASM. We used the ansamycin antibiotic GA to inhibit Hsp90 activity in vitro. Although GA has been commonly used as a “specific” inhibitor of Hsp90, there is evidence for nonspecific effects. For example, Dikalov et al. (2002) have demonstrated that GA can lower NO bioavailability by generating superoxide—an effect that would attenuate estrogen-stimulated (NO-dependent) coronary relaxation (White et al., 2005). In addition, long-term exposure to high concentrations of GA may suppress nNOS activity (Bender et al., 1999). Therefore, we also used RAD, a more specific Hsp90 inhibitor, and again observed a significant inhibition of estrogen-induced relaxation. Taken together, these pharmacological studies strongly suggest an essential role for Hsp90 in mediating estrogen-induced relaxation of coronary arteries.

We have shown previously that estrogen stimulates nNOS activity in CASM to enhance BKCa channel activity via a rapid, nongenomic mechanism of action (White et al., 2002, 2005; Han et al., 2007). In support of this conclusion are recent studies indicating that nNOS mediates estrogen action in urethral smooth muscle as well (Hayashi et al., 2007). The present findings now demonstrate a role for Hsp90 in estrogen signaling in CASM. Thus, Hsp90 seems to play an essential role in coupling ER activation to nNOS function in CASM, with subsequent membrane repolarization and coronary artery relaxation being the ultimate result of estrogen action under normal conditions. Although such an essential role for Hsp90 in mediating estrogen signaling has not been reported previously in smooth muscle, there is evidence that activity of nNOS can be regulated by scaffolding proteins and that Hsp90 can potentiate nNOS activity in other cell types (Bender et al., 1999; Song et al., 2001).

In addition to the more classic genomic signaling mediated by nuclear ERs, estrogen can produce rapid, nongenomic effects mediated by signaling elements that seem to be colocalized in proximity to the plasma membrane, probably in or near caveolae. Such clusters of functionally associated estrogen signaling components have been found in neuronal cells (Luoma et al., 2008) and vascular endothelial cells (Kim et al., 2008), and there is evidence that Hsp90 is a key element in this acute signaling process. For example, several studies have reported that estrogen enhances association of Hsp90 with eNOS in vascular endothelial cells (Russell et al., 2000; Bucci et al., 2002; Schulz et al., 2005), thus producing NO and vasorelaxation. Likewise, nNOS seems to be localized to caveolae in both skeletal (Venema et al., 1997) and vascular smooth muscle (Segal et al., 1999), and it is associated with caveolin-1 that inhibits nNOS activity by interfering with calcium/calmodulin binding (Venema et al., 1997). In light of our present findings that estrogen stimulates Hsp90 association with nNOS in CASM, it would seem likely that Hsp90 helps to disinhibit nNOS activity and thereby facilitate estrogen signaling in this tissue. One possible mechanism of estrogen-stimulated nNOS activation could be related to relieving some of the negative influence of caveolin-1; however, we have recently demonstrated that acute estrogen signaling in CASM also involves activity of the PI3-kinase-Akt signaling system (Han et al., 2007). Thus, there are at least two possible mechanisms whereby estrogen enhances nNOS activity in CASM: 1) association of Hsp90 with nNOS and 2) PI3-kinase-Akt-dependent phosphorylation.

Somewhat surprisingly, we found that although ICI182,780 prevented estrogen-stimulated association of Hsp90 with nNOS, this high-affinity ER antagonist induced coronary relaxation in the absence of estrogen. This endothelium-independent action also seems to be independent of nNOS activity, because we have previously demonstrated that ICI182,780 does not enhance NO production in CASM (Han et al., 2006). These findings now suggest a novel, nongenomic estrogen signaling mechanism in coronary arteries that does not involve classic ER stimulation but might instead be mediated by GPR30. GPR30 has been identified in cancer cells and cell lines and is believed to mediate effects of estrogen on protein transcription and proliferation (Filardo et al., 2000; Prossnitz et al., 2008). Although ICI182,780 is widely used to block classic ER in cardiovascular experiments, it is also an agonist of GPR30 (Prossnitz et al., 2007); however, a functional role for GPR30 in the cardiovascular system has not been described previously. Thus, our findings argue for distinct mechanisms of estrogen-induced CASM relaxation: 1) nNOS and 2) GPR30, which now constitutes a potential mechanism to account for the RAD- and l-NAME-insensitive component of estrogen-induced coronary artery relaxation (Fig. 1). It is unclear whether Hsp90 is coupled functionally to GPR30 or whether this chaperone regulates activity of this novel estrogen signaling pathway. Nonetheless, it is clear that there is a redundancy of estrogen signal transduction mechanisms in vascular smooth muscle.

Taken together, our findings indicate an essential role for Hsp90 in nongenomic estrogen signaling in CASM, and further suggest that Hsp90 might represent a prospective therapeutic target to enhance estrogen-stimulated cardiovascular protection. For example, we have recently demonstrated that estrogen can produce either NO or superoxide in CASM depending on the biochemical state of nNOS (i.e., coupled or uncoupled) and suggested that estrogen-stimulated production of reactive oxygen species could contribute to the pathologies associated with long-term estrogen replacement therapy (White et al., 2005, 2007). It is noteworthy that Hsp90 is known to directly inhibit superoxide generation from nNOS (Song et al., 2002) and thereby might exert a protective influence on cellular function, especially in older women. Recent studies indicate that association of Hsp90 with NOS (i.e., eNOS) declines with age (Smith et al., 2006), suggesting that Hsp90 may be less protective of vascular function in older women. Thus, diminished Hsp90 function may contribute to age-dependent declines in post-translational regulatory mechanisms that help maintain optimal NOS activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Louise Meadows and Nancy Godin for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants HL073890, HL080402, HL068026, HL074279].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.108.149112.

ABBREVIATIONS: ER, estrogen receptor; PI3-kinase, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; CASM, coronary artery smooth muscle; NOS, nitric-oxide synthase; nNOS, neuronal nitric-oxide synthase; Hsp90, 90-kDa heat shock protein; PG, prostaglandin; GA, geldanamycin; RAD, radicicol; l-NAME, Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester; ICI182780, fulvestrant; NPo, channel open-state probability; BKCa, large-conductance, calcium- and voltage-activated potassium channel; DAF-2 DA, 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate; GPR30, G protein-coupled receptor 30 involved in rapid nongenomic estrogen-mediated signaling; E2, 17β-estradiol.

References

- Bender AT, Silverstein AM, Demady DR, Kanelakis KC, Noguchi S, Pratt WB, and Osawa Y (1999) Neuronal nitric-oxide synthase is regulated by the Hsp90-based chaperone system in vivo. J Biol Chem 274 1472-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal RS, Heldman AW, Brinker JA, Resar JR, Coombs VJ, Gloth ST, Gerstenblith G, and Reis SE (1997) Acute effects of conjugated estrogens on coronary blood flow response to acetylcholine in men. Am J Cardiol 80 1021-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci M, Roviezzo F, Cicala C, Pinto A, and Cirino G (2002) 17-beta-Oestradiol-induced vasorelaxation in vitro is mediated by eNOS through hsp90 and akt/pkb dependent mechanism. Br J Pharmacol 135 1695-1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Yuhanna IS, Galcheva-Gargova Z, Karas RH, Mendelsohn ME, and Shaul PW (1999) Estrogen receptor alpha mediates the nongenomic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen. J Clin Invest 103 401-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkow DJ, Lu L, and White RE (1997) Estrogen relaxation of coronary artery smooth muscle is mediated by nitric oxide and cGMP. Am J Physiol 272 H2765-H2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalov S, Landmesser U, and Harrison DG (2002) Geldanamycin leads to superoxide formation by enzymatic and non-enzymatic redox cycling. Implications for studies of Hsp90 and endothelial cell nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 277 25480-25485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, and Frackelton AR Jr (2000) Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol 14 1649-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan DM, Quyyumi AA, and Cannon RO 3rd (1994) Effects of physiological levels of estrogen on coronary vasomotor function in postmenopausal women. Circulation 89 2545-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollasch M, Ried C, Bychkov R, Luft FC, and Haller H (1996) K+ currents in human coronary artery vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 78 676-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Kryman JP, McMillin PJ, White RE, and Carrier GO (1999) A novel transduction mechanism mediating dopamine-induced vascular relaxation: opening of BKCa channels by cyclic AMP-induced stimulation of the cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 34 619-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Ma H, Chintala R, Miyake K, Fulton DJ, Barman SA, and White RE (2007) Nongenomic, endothelium-independent effects of estrogen on human coronary smooth muscle are mediated by type I (neuronal) NOS and PI3-kinase-Akt signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293 H314-H321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Yu X, Lu L, Li S, Ma H, Zhu S, Cui X, and White RE (2006) Estrogen receptor alpha mediates acute potassium channel stimulation in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316 1025-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, Mitchell BM, Sood SG, Webb RC, and Venema RC (2008) Increased nitric oxide synthase activity and Hsp90 association in skeletal muscle following chronic exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 104 795-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi N, Bella AJ, Wang G, Lin G, Deng DY, Nunes L, and Lue TF (2007) Effect of extended-term estrogen on voiding in a postpartum ovariectomized rat model. Can Urol Assoc J 1 256-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes MP, Sinha D, Russell KS, Collinge M, Fulton D, Morales-Ruiz M, Sessa WC, and Bender JR (2000) Membrane estrogen receptor engagement activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase via the PI3-kinase-Akt pathway in human endothelial cells. Circ Res 87 677-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Moriarty K, and Bender JR (2008) Vascular cell signaling by membrane estrogen receptors. Steroids 73 864-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JI, Boulware MI, and Mermelstein PG (2008) Caveolin proteins and estrogen signaling in the brain. Mol Cell Endocrinol 290 8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijic J and Toro L (2001) Voltage and calcium-activated K+ channels of coronary smooth muscle, in Heart Physiology and Pathophysiology (Sperelakis N, Kurachi Y, Terzic A, and Cohen MV eds) pp 309-325, Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Mügge A, Riedel M, Barton M, Kuhn M, and Lichtlen PR (1993) Endothelium independent relaxation of human coronary arteries by 17 beta-oestradiol in vitro. Cardiovasc Res 27 1939-1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, and Sklar LA (2007) GPR30: a G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen. Mol Cell Endocrinol 265–266: 138-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Smith HO, Oprea TI, Sklar LA, and Hathaway HJ (2008) Estrogen signaling through the transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor GPR30. Annu Rev Physiol 70 165-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis SE, Gloth ST, Blumenthal RS, Resar JR, Zacur HA, Gerstenblith G, and Brinker JA (1994) Ethinyl estradiol acutely attenuates abnormal coronary vasomotor responses to acetylcholine in postmenopausal women. Circulation 89 52-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell KS, Haynes MP, Caulin-Glaser T, Rosneck J, Sessa WC, and Bender JR (2000) Estrogen stimulates heat shock protein 90 binding to endothelial nitric oxide synthase in human vascular endothelial cells. Effects on calcium sensitivity and NO release. J Biol Chem 275 5026-5030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz E, Anter E, Zou MH, and Keaney JF Jr (2005) Estradiol-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase association with heat shock protein 90 requires adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Circulation 111 3473-3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal SS, Brett SE, and Sessa WC (1999) Codistribution of NOS and caveolin throughout peripheral vasculature and skeletal muscle of hamsters. Am J Physiol 277 H1167-H1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Visioli F, and Hagen TM (2006) Plasma membrane-associated endothelial nitric oxide synthase and activity in aging rat aortic vascular endothelia markedly decline with age. Arch Biochem Biophys 454 100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Cardounel AJ, Zweier JL, and Xia Y (2002) Inhibition of superoxide generation from neuronal nitric oxide synthase by heat shock protein 90: implications in NOS regulation. Biochemistry 41 10616-10622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Zweier JL, and Xia Y (2001) Heat-shock protein 90 augments neuronal nitric oxide synthase activity by enhancing Ca2+/calmodulin binding. Biochem J 355 357-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venema VJ, Ju H, Zou R, and Venema RC (1997) Interaction of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase with caveolin-3 in skeletal muscle. Identification of a novel caveolin scaffolding/inhibitory domain. J Biol Chem 272 28187-28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RE, Darkow DJ, and Lang JL (1995) Estrogen relaxes coronary arteries by opening BKCa channels through a cGMP-dependent mechanism. Circ Res 77 936-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RE, Han G, and Barman SA (2007) Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular function: evidence for dual and opposite effects of estrogen on vascular reactivity. Curr Top Pharmacol 11 17-26. [Google Scholar]

- White RE, Han G, Dimitropoulou C, Zhu S, Miyake K, Fulton D, Dave S, and Barman SA (2005) Estrogen-induced contraction of coronary arteries is mediated by superoxide generated in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289 H1468-H1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RE, Han G, Maunz M, Dimitropoulou C, El-Mowafy AM, Barlow RS, Catravas JD, Snead C, Carrier GO, Zhu S, et al. (2002) Endothelium-independent effect of estrogen on Ca2+-activated K+ channels in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res 53 650-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]