Torpedoes, swellings of the proximal Purkinje cell axon, are thought to represent a cellular response to injury [3]. They may occur in a variety of cerebellar disorders [7]. Most recently, their numbers were noted to be six-times higher in essential tremor (ET) than control brains [4]. Torpedoes are also often viewed as a cumulative phenomenon associated with advanced aging [3,4], yet there are surprisingly few supporting data. We quantified torpedoes in normal human cerebella spanning a considerable age range to assess whether torpedoes are a cumulative phenomenon of aging. These data help place the relative abundance of torpedoes in ET in context.

Control brains at the New York Brain Bank, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) had been controls in the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center or non-neurologic patients at CUMC. Each had a complete neuropathologic assessment [4] including Braak AD stage [2] and CERAD [5] for Alzheimer’s tangle and plaque pathologies.

As documented [4], a standard 3 × 20 × 25 mm parasagittal tissue block was harvested from each neocerebellum (N = 48) and immersion-fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Paraffin sections (7 μm thick) were stained with Luxol Fast Blue counterstained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (LH&E) [4]. Torpedoes (Figure 1) in one entire LH&E section were counted blinded to age. Purkinje cells in five randomly-selected 100x LH&E stained fields of the standard cerebellar section were counted and the mean reported. In 32 brains, a second set of sections from the same blocks were used as replicate data.

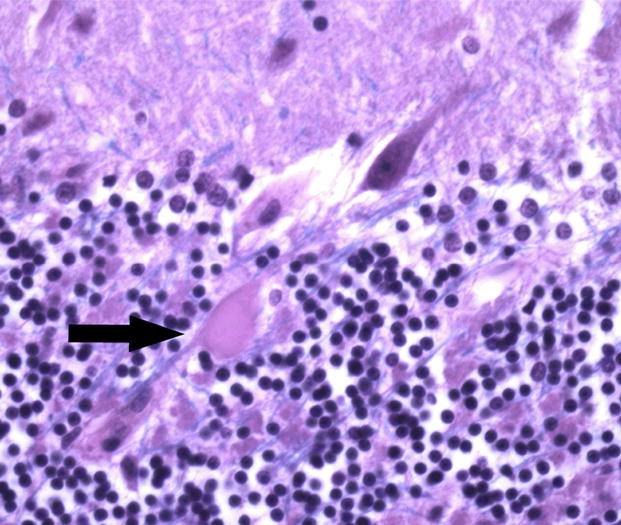

Figure 1.

Control cerebellar tissue showing a torpedo (arrow). LH&E 400x magnification.

Non-parametric tests (Spearman’s r, Mann Whitney test, Kruskal Wallis test) were used. Because of zero values (0 torpedoes), in linear regression analyses, log10(torpedoes +1) was the dependent variable and age, the independent variable.

Age at death ranged from 6–93 years. Mean±SD (median, range) number of torpedoes = 1.8±2.1 (1, 0–11)(Table).

Table.

Clinical characteristics/postmortem features (48 controls)

| Clinical/postmortem features | Torpedoes on LH&E | Correlation (r) between clinical/postmortem feature and torpedoes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death (years) | 58.7±25.1 | 0.35, p = 0.02 | |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Women | 20(41.7) | 2.5±2.5 (2) | |

| Men | 28(58.3) | 1.4±1.6 (1) | |

| p = 0.05 | |||

|

| |||

| Cause of Death | |||

| Cardio-pulmonary | 19(39.6) | 2.5±2.7 (2) | |

| Cancer | 9(18.8) | 1.1±1.6 (1) | |

| Other | 11(22.9) | 1.5±1.6 (1) | |

| Unknown | 9(18.8) | 1.6±1.3 (1) | |

| p = 0.31 | |||

|

| |||

| PMI (hours) | 7.2±7.1 | 0.13, p = 0.51 | |

|

| |||

| Brain weight (grams) | 1298±152 | −0.20, p = 0.22 | |

|

| |||

| Torpedoes | 1.8±2.1 | ||

|

| |||

| Purkinje cells | 9.2±2.5 | −0.13, p = 0.40 | |

|

| |||

| CERAD plaque score | 0.2±0.5 | 0.14, p = 0.35 | |

|

| |||

| Braak stage | 0.5±1.0 | 0.03, p = 0.82 | |

Mean±SD (median) or counts(%).

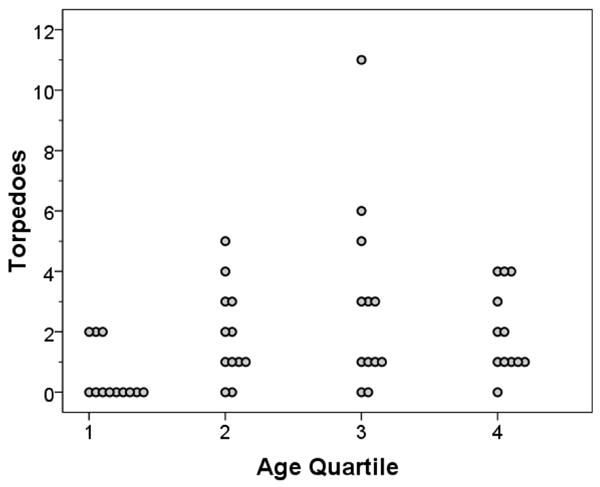

Number of torpedoes was correlated with age at death (r = 0.35, p = 0.02, Table), but not when the brains in the youngest age quartile (≤36 years) were excluded (i.e., in brains with age of death ranging from 37–93 years, r = −0.03, p = 0.85). While (mean±SD, median) number of torpedoes was low in brains in the youngest quartile (quartile 1, ≤36 years, 0.5±0.9, 0), it did not differ among brains in the remaining 3 quartiles: quartile 2 (37–63 years) 1.9±1.6, 1.5; quartile 3 (64–80 years) 2.9±3.2, 2; quartile 4 (≥81 years) 2.0±1.4, 1.5 (for comparison of quartiles 2–4, p = 0.88)(Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of torpedoes (Y axis) by age at death quartile (X axis).

In a linear regression analysis, log-transformed number of torpedoes was associated with age (beta 0.004, p = 0.01) but not in a fully adjusted model including gender, race, postmortem interval (PMI), brain weight, number of Purkinje cells, CERAD plaque score and Braak stage(beta for age −0.003, p = 0.71). In unadjusted and adjusted models restricted to age quartiles 2–4, beta = −0.001, p = 0.70 and beta = −0.003 and p = 0.69, respectively.

The results of replicate analyses on 32 brains were similar to our primary analyses. The number of torpedoes was lowest in the youngest age quartile (0.2±0.4, 0) but was similar in the remaining three age quartiles (quartile 2: 1.8±1.9, 2; quartile 3: 3.2±2.3, 3.5; quartile 4: 2.7±2.4, 2.5)(for comparison of quartiles 2–4, p = 0.82).

We examined control brains spanning a wide age range. Torpedoes were rare in the first four decades of life, but thereafter, there was no aging-associated increase. Torpedoes have been commented on as rare incidental findings in normal human control brains, although it has not been demonstrated that they are more abundant as a function of advanced age. One study [3] examined 32 axons in three normal individuals (ages 64, 70, 86). The 86 year old had two torpedoes. In a study of two normal mouse strains (age 8 days - 32 months)[1], <0.1% of Purkinje cells had torpedoes at 6 months; this increased linearly to 13.7% by age 32 months [1]. However, in a study of other normal mice strains, torpedoes were absent, suggesting that torpedoes are not a “simple aging phenomena” [6]. The lack of an association here between these lesions and advanced aging suggests that the abundance of these lesions in ET is a marker of cerebellar injury and not merely representative of accelerated aging.

Acknowledgments

R01NS42859 (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Statistical Analyses: The statistical analyses were conducted by Dr. Louis.

References

- 1.Baurle J, Grusser-Cornehls U. Axonal torpedoes in cerebellar Purkinje cells of two normal mouse strains during aging. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;88:237–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00293399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato T, Hirano A. A Golgi study of the proximal portion of the human Purkinje cell axon. Acta Neuropathol. 1985;68:191–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00690193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP, et al. Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain. 2007;130:3297–3307. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirra SS. The CERAD neuropathology protocol and consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a commentary. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S91–S94. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki K, Zagoren JC. Focal axonal swelling in cerebellum of quaking mouse: light and electron microscopic studies. Brain Res. 1975;85:38–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)91001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaginuma M, Ishida K, Uchihara T, et al. Paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia with mild cerebello-olivary degeneration and an anti-neuronal antibody: a clinicopathological study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26:568–571. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2000.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]