Abstract

Coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX) catalyzes the two-step decarboxylation of coproporphyrinogen-III to protoporphyrinogen-IX in the heme biosynthetic pathway. Previously we described a specific polymorphism (A814C) in exon 4 of the human CPOX gene (CPOX4) and demonstrated that CPOX4 is associated with both modified urinary porphyrin excretion and increased neurobehavioral deficits among human subjects with low-level mercury (Hg) exposure. Here, we sought to characterize the gene products of CPOX and CPOX4 with respect to biochemical and kinetic properties. Coproporphyrinogen-III was incubated with recombinantly expressed and purified human CPOX and CPOX4 enzymes at various substrate concentrations, with or without Hg2+ present. Both CPOX and CPOX4 formed protoporphyrinogen-IX from coproporphyrinogen-III; however, the affinity of CPOX4 was twofold lower than that of CPOX (CPOX Km = 0.30μM, Vmax = 0.52 pmol protoporphyrin-IX; CPOX4 Km = 0.54μM, Vmax = 0.33 pmol protoporphyrin-IX). Hg2+ specifically inhibited the second step of coproporphyrinogen-III decarboxylation (harderoporphyrinogen to protoporphyrinogen-IX) in a dose dependent manner. We also compared the catalytic activities of CPOX and CPOX4 in human liver samples. The specific activities of CPOX in mutant livers were significantly lower (40–50%) than those of either wild-type or heterozygous. Additionally, enzymes from mutant, heterozygous and wild-type livers were comparably inhibited by Hg2+ (10μM), decreasing CPOX4 activity to 25% that of the wild-type enzyme. These findings suggest that CPOX4 may predispose to impaired heme biosynthesis, which is limited further by Hg exposure. These effects may underlie increased susceptibility to neurological deficits previously observed in Hg-exposed humans with CPOX4.

Keywords: coproporphyrinogen oxidase, polymorphism, CPOX4, Hg

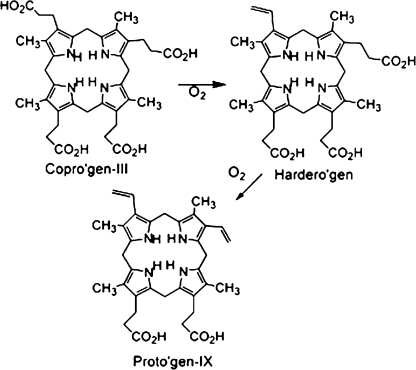

Coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX) (EC 1.3.3.3), the sixth enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1), catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of the propionic acid side chains on rings A and B of coproporphyrinogen-III to vinyl groups, producing protoporphyrinogen-IX. In this two-step reaction, the first carboxyl group is removed producing an intermediate three carboxyl porphyrinogen, harderoporphyrinogen (Kennedy et al., 1970), from which the second carboxyl group is subsequently removed (Elder et al., 1978) (Fig. 2). Whereas the catalytic activity of CPOX is localized to the intermembranal space of the mitochondria (Elder and Evans, 1978; Grandchamp et al., 1978), human CPOX is synthesized in the cytosol as a larger precursor protein containing 100 amino acid mitochondria leading sequence. These 100 amino acids are cleaved after it has been transported to the mitochondria, although the specific transporter remains unknown (Susa et al., 2003). Human cDNAs encoding CPOX have been sequenced (Martasek et al., 1994a; Taketani et al., 1994), and the structures of both the human CPOX gene and the CPOX protein have been determined (Delfau-Larue et al., 1994; Lee et al., 2005; Taketani et al., 1994).

FIG. 1.

Heme biosynthetic pathway. (1) ALA synthetase, (2) ALA dehydratase, (3) PBG deaminase, (4) uroporphyrinogen III cosynthetase, (5) uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), (6) coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX), (7) protoporphyrinogen oxidase, (8) ferrochelatase.

FIG. 2.

Coproporphyrin, harderoporphyrin, and protoporphyrin. Porphyrin structures adapted from Lash et al. (1999).

The CPOX protein contains a number of reduced thiol residues that render it potentially susceptible to inhibition by thiol binding agents including metals (Yoshinaga and Sano, 1980). In this regard, we have previously shown (Woods and Fowler, 1987; Woods and Southern, 1989) that CPOX activity is significantly impaired by mercury (Hg) as either CH3Hg+ or Hg2+ both in vivo and in vitro, and that this effect is expressed predominantly in the kidney, a principal target organ of Hg compounds. We have also demonstrated that partial inhibition of renal CPOX activity by Hg produces a characteristic change in the urinary porphyrin excretion pattern that serves as a biological indicator of Hg exposure and toxicity in both animals and humans (Bowers et al., 1992; Woods et al., 1991, 1993). In more recent studies (Woods et al., 2005), we have found that 12–16% of human subjects respond atypically to Hg exposure in terms of porphyrin excretion and have shown that this atypical response is associated with an A814C single nucleotide polymorphism in exon 4 of the CPOX gene that results in an asparagine to histidine change at amino acid 272 (N272H) in the protein structure. This polymorphism (CPOX4) was first reported in a hereditary coproporphyria (HCP) case study (Martasek et al., 1994b), but because it was found not to be responsible for the CPOX defect in HCP, this specific mutation was not further characterized. However, our subsequent studies in a large cohort of human subjects with occupational Hg exposure have shown that CPOX4 not only significantly modifies the effect of Hg on urinary porphyrin excretion (Woods et al., 2005) but also is associated with increased reporting of adverse symptoms and mood as well as with significant neurobehavioral deficits among Hg-exposed subjects (Echeverria et al., 2006).

In the present study, we sought to characterize the gene products of CPOX and CPOX4 with respect to kinetic properties, product generation, thermostability, reactivity toward Hg, and other biochemical characteristics in vitro. Studies employed both recombinant wild-type and mutant CPOX proteins as well as human livers from subjects genotyped as WT (AA), Het (AC), or Mut (CC) with respect to A814C status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CPOX4 Plasmid Preparation

The CPOX cDNA-pGEX-2T expression construct was generously provided by Dr B. Grandchamp. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the wild-type CPOX cDNA (A814) to generate the CPOX4 mutant clone (C814). The QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to achieve this goal. The following primers were used to change nucleotide A814 (wild-type CPOX) to C814 (CPOX4): 5′-CCCTTGTGAAAAAGCCCTGTGATGACTCATTCAC-3′ (sense primer), 5′-GTGAATGAGTCATCACAGGGCTTTTTCACAAGGG-3′ (antisense primer). Escherichia coli–competent cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were transformed according to company's protocols. Plasmid DNA was isolated from single colonies and cDNA inserts were sequenced to confirm their fidelity.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Wild-type and Mutant CPOX Proteins

The wild-type and mutant CPOX cDNA-pGEX-2T expression constructs were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3), as described in company instructions (Invitrogen). CPOX-glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins were purified from bacterial lysates by Bulk and RediPack GST Purification Modules (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). The GST-tag was cleaved out by Thrombin CleanCleave KIT (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Purity of the recombinant proteins was judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Commassie Blue staining (Sigma).

CPOX Activity Assay

Substrate preparation.

0.1 nmol coproporphyrin-III tetramethyl ester (Sigma) was dissolved in 1 ml of 8.3M HCl, and the solution was kept in the dark for 16 h or longer to remove the methyl esters. HCl was evaporated by vacuum for 5–6 h and 1 ml of 0.05M KOH was added immediately before experiments. To reduce the coproporphyrin to coproporphyrinogen, 100 mg 5% sodium amalgam (Sigma) was added to 1 ml of coproporphyrin-III solution on ice and flushed with N2 until the solution became clear. Nine milliliters of cold 0.25M Tris-HCl, pH7.2, buffer was then added to 1 ml of reduced coproporphyrinogen-III. The final concentration of coproporphyrinogen-III was 10μM.

CPOX activity assay.

Two micromolars of coproporphyrinogen-III was incubated with 1–5 μg purified enzyme (CPOX or CPOX4) in sufficient 0.25M Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, buffer to constitute a total reaction volume of 250 μl. Reactions were carried out at 37°C in the dark for 60 min. A blank assay was conducted in parallel with the above assay using CPOX denatured by boiling for 10 min. The reactions were terminated by adding 250 μl of 20% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid/dimethylsulfoxide (1:1 vol/vol) in ice. Proteins were precipitated by centrifuging at 2100 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Protoporphyrinogen oxidation was completed by allowing the mixture to stand under overhead light for one hour. Protoporphyrin-IX was quantitatively analyzed by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Twenty microliters of samples was injected for each reaction mixture. The separation was performed by C18 column (Alltech, Lexington, KY) chromatography with a gradient of methanol and 20mM phosphate buffer, pH 3.5, as described (Woods et al., 1991).

Thermostability assays.

Two micrograms of purified CPOX or CPOX4 was preincubated with 2μM coproporphyrinogen-III at 50°C for 15 min then incubated at 37°C in the dark for 60 min. Protoporphyrin-IX was measured and compared with duplicate samples run without 50°C preincubation.

CPOX and CPOX4 kinetics.

Two micrograms of purified CPOX or CPOX4 was incubated with 0, 0.2, 0.4, 1, 2, 4, or 6μM coproporphyrinogen-III at 37°C in the dark for 15 min. Protoporphyrin-IX was measured by reverse phase HPLC as described above. Double reciprocal plots were created by CurveExpert 1.3 (http://home.comcast.net/∼curveexpert/).

Human Liver CPOX Activity Assays

Human liver samples were acquired from the University of Washington School of Pharmacy human tissue bank and the St Jude Children's Hospital liver bank (Memphis, TN). All were genotyped providing 16 wild-type (AA, WT), 16 heterozygous (AC, Het), and 5 CPOX4 mutant (CC, Mut), samples. Mitochondrial fractions were isolated according to established protocol as follows: 300 mg of each human liver sample was rinsed in a cold solution (4°C) of 0.25M sucrose, 0.07M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, then minced well with scissors and homogenized. The homogenate was centrifuged at 2500 × g for 10 min to remove nuclei and cell debris. The supernatant was spun at 10,000 × g for 10 min to form a primary mitochondrial pellet. The mitochondrial pellet was gently resuspended in 10 ml Tris-sucrose buffer and spun again at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The final mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in a 0.25mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, enzyme activity buffer. Two hundred milligrams of mitochondrial protein was incubated with 2μM coproporphyrinogen-III at 37°C in the dark for 60 min. Protoporphyrin-IX was quantitated by reverse phase HPLC as described above.

Human Liver CPOX Western Blots

Total protein content was measured by bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of mitochondrial protein (80 μg) were loaded onto 4–12% bis-tris 10 wells 1.5-mm mini gels (Invitrogen) and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) by electroblotting. Anti human CPOX IgG was custom-made for this project by Proteintech Group, Inc (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

CPOX4 Expresses Decreased Activity Toward Coproporphyrinogen-III as Substrate

Both CPOX and CPOX4 utilized coproporphyrinogen-III as a substrate to produce protoporphyrinogen-IX through the intermediate product, harderoporphyrinogen. However, as shown in Figure 3A, CPOX4 produced approximately 50% less protoporphyrinogen-IX in a concentration-dependent manner compared with the wild-type enzyme. The time-dependent accumulation of protoporphyrinogen-IX shown in Figure 3B indicates that CPOX4 produced significantly less protoporphyrinogen-IX than CPOX at every time point.

FIG. 3.

The accumulation of protoporphyrin-IX with the coproporphyrinogen-III substrate in an enzyme dose- and time-dependent manner. (A) The enzyme dependent accumulation of protoporphyrin-IX with the coproporphyrinogen-III substrate. Different amounts (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 μg) of CPOX or CPOX4 were incubated with 2μM coproporphyrinogen-III for 60 min at 37°C in the dark. The amount of product (protoporphyrin-IX) was measured by HPLC as μmol in 250 μl of reaction mixture. (B) Time course experiments for CPOX and CPOX4 using coproporphyrinogen-III as substrate showing the amount of product (protoporphyrin-IX) formed verses time. Two micrograms of CPOX or CPOX4 was incubated with 2μM coproporphyrinogen-III for different times (0, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min) at 37°C in the dark. The amount of product (protoporphyrin-IX) was measured by HPLC as μmol in 250 μl of reaction mixture. All values are the mean of three replicate assays. Error bars represent standard deviations between three replicate assays. **p < 0.01.

Figure 4 shows the kinetics of CPOX (Fig. 4A) and CPOX4 (Fig. 4B) when using coproporphyrinogen-III as substrate. Specifically depicted are the velocities of substrate utilization (pmol product/min/μg enzyme) over a substrate concentration range of 0.2–6μM. The kinetic constants (Km, Vmax, Kcat) for these reactions are shown in Table 1. Michaelis-Menton functions were used to graph the data and to obtain the kinetic constants, Km and Vmax. There is a 1.8-fold increase in Km, a 1.6-fold decrease in Vmax, and threefold increase in Kcat for CPOX4 relative to CPOX.

FIG. 4.

Coproporphyrinogen oxidase enzyme kinetics curves. Velocity (pmol product/min/μg enzyme) is shown as a function of substrate over a concentration range of 0.2–6μM using coproporphyrinogen-III. (A) CPOX enzyme kinetics curve. (B) CPOX4 enzyme kinetics curve. All values are the mean of three replicate assays. Error bars represent standard deviations between three replicate assays.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic Constants for CPOX and CPOX4

| Km (μM) | Vmax (pmol protoporphyrinogen-IX/min/μg) | Kcat | |

| CPOX | 0.291 | 0.522 | 1.794 |

| CPOX4 | 0.537 | 0.332 | 0.618 |

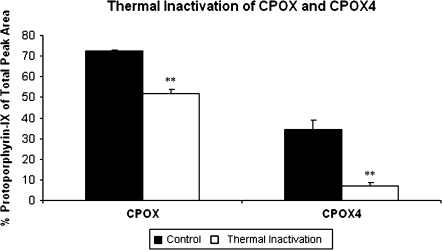

Thermal Inactivation of CPOX4

Figure 5 compares the effects of thermal denaturation on CPOX and CPOX4 activities. Preincubation enzyme with substrate at 50°C for 15 min resulted in diminished CPOX activity by 30% and diminished CPOX4 activity by 80% compared with control samples run without thermal denaturation.

FIG. 5.

Thermal inactivation of CPOX and CPOX4 proteins. Two micrograms of purified CPOX or CPOX4 was preincubated with 2μM coproporphyrinogen-III at 50°C for 15 min then incubated at 37°C in the dark for 60 min. Protoporphyrin-IX was measured and compared with controls (i.e., identical samples without preincubation). Protoporphyrin-IX was measured as % protoporphyrin-IX peak area of total porphyrin area. All values are the mean of three replicate assays. Error bars represent standard deviations between three replicate assays. **p < 0.01.

Effects of Hg2+ on CPOX and CPOX4 Activities

Figure 6 presents a stereo ribbon structural depiction of the mutant CPOX4 protein, showing the N272H mutation site and the active site of the enzyme (shown in stick) as well as all cysteine moieties (in red), potential Hg2+ binding sites. The N272 is away from the catalytic site. Only one cysteine moiety, C319 is located on the same side of the beta sheet of the protein as the active site. None of the cysteines is in the dimer interface of the biological dimer. Based on these structural characteristics, we do not expect Hg2+ to completely inactivate the mutant enzyme.

FIG. 6.

Stereo view ribbon diagram showing closed conformation of human coproporphyrinogen oxidase, CPOX4 mutation site, active site of the enzyme as well as the all cysteines (potential Hg binding sites). All cysteines are shown in red. The citric acid (shown in stick) seen in the crystal structure resides in the active site of the enzyme. CPOX4 mutation (N272) is shown in green.

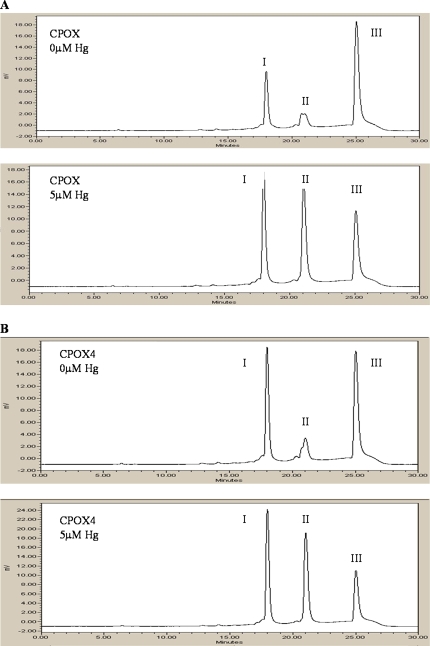

To evaluate the effects of Hg2+ on CPOX and CPOX4 enzyme activities in vitro, we performed assays with the recombinant enzymes in the presence of various concentrations of Hg2+ as HgCl2 in reaction mixtures. As shown in Figures 7A and 7B, the principal effect of Hg2+ was to significantly inhibit the conversion of harderoporphyrinogen to protoporphyrinogen in both CPOX and CPOX4 reactions while also promoting coproporphyrinogen accumulation by both enzymes. Because a standard for harderoporphyrin is not commercially available to our knowledge, we quantified harderoporphyrin in these reactions as percent of total porphyrin peak areas. To make the results comparable, we quantified protoporphyrin-IX as a percentage of total porphyrin peak areas as well. As shown in Figure 8A, both CPOX and CPOX4 produced significantly less protoprophyrinogen-IX with increased Hg2+ concentrations. The harderoporphyrinogen accumulation also followed in a Hg2+ concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8B). These results indicate that Hg2+ preferentially inhibits the second decarboxylation step (harderoporphyrinogen to protoprophyrinogen-IX) in the CPOX enzymatic reactions. Notably, however, the magnitude of protoporphyrinogen decrease as well as harderoporphyrinogen increase for both CPOX and CPOX4 are almost equal (lines are parallel), indicating that Hg2+ inhibits wild-type and mutant enzymes to a comparable extent over a wide range of concentrations. Nonetheless, at the same concentration, the effect of Hg2+ on protoporphyrinogen-IX production by CPOX4 is greater than by CPOX owing to the decreased affinity of CPOX4 for coproporphyrinogen-III as substrate compared with that of the wild-type enzyme.

FIG. 7.

Representative HPLC chromatograms of porphyrin products resulting from incubation of coproporphyrinogen-III, CPOXs, and HgCl2. 0 or 5μM HgCl2 were coincubated with 2μM coproporphyrinogen-III and 2 μg CPOX or CPOX4 for 60 min at 37°C in the dark. (A). Representative HPLC chromatogram of CPOX with 0μM HgCl2 (top) and 5μM HgCl2 (bottom). Peak I is the substrate coproporphyrinogen-III; peak II is the intermediate product harderoporphyrin; Peak III is the final product protoporphyrin-IX. (B) Representative HPLC chromatogram of CPOX4 with 0μM HgCl2 (top) and with 5μM HgCl2 (bottom). Peak I is the substrate coproporphyrinogen-III; peak II is the intermediate product harderoporphyrin; peak III is the final product protoporphyrin-IX.

FIG. 8.

Hg inhibition on CPOX and CPOX4 enzymes using coproporphyrinogen-III as the substrate. CPOX or CPOX4 (2 μg) was incubated with 2μM coproporphyrinogen-III and various Hg2+ concentrations (0, 1, 2, 5, or 10μM) for 60 min at 37°C in the dark. Porphyrin products (protoporphyrin-IX and harderoporphyrin) were measured as % porphyrin peak area of total porphyrin area. (A) Hg2+ effects on protoporphyrin-IX production. (B) Hg2+ effects on harderoporphyrin accumulation. All values are the mean of three replicate assays. Error bars represent standard deviation between three replicate assays.

Human Liver CPOX Protein Levels

Western blot analyses were performed on all liver samples. The results revealed a notable heterogeneity in the individual mitochondrial contents of CPOX protein. As shown in Figure 9, depicting 4 randomly selected CPOX WT samples (lanes 1–4) and all 5 CPOX4 samples (lanes 5–9), two mutant samples (lanes 6 and 10) had 50% lower protein content than WT. However, no significant difference was observed in the protein content of other Mut samples (lanes 5,7,8) compared with those of WT and Het.

FIG. 9.

Human liver CPOX and CPOX4 protein level (western blot). Human liver mitochondrial fractions were analyzed for wild-type (CPOX) and mutant (CPOX4) protein contents. The blot was reprobed with actin antibody to show equal loading. Lanes 1–4: Wild-type; Lanes 5–9: Mutant. Accompanying bars represent individual band intensities.

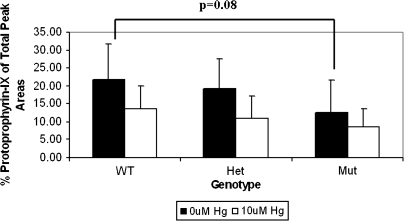

Human Liver CPOX Enzyme Activities

Consistent with the above findings with recombinant enzymes, CPOX activity (measured as production of protoporphyrinogen-IX) in Mut liver samples was found to be approximately 50% that seen with the enzyme from wild-type livers, with intermediate activity in Het liver samples (Fig. 10). The difference between mean enzyme activities in WT versus Mut livers achieved near statistical significance (p = 0.08) owing to fairly large interindividual variability among the relatively few samples available for testing. Notably also, coincubation with 10μM HgCl2 decreased protoporphyrinogen-IX yields in all three genotypes by 30–50%, similar to findings observed in assays with recombinant enzymes. A higher concentration of HgCl2 was employed in these human liver studies to compensate for the higher protein content in the reaction mixtures.

FIG. 10.

Human liver CPOX activities. The average of enzyme activities toward coproporphyrinogen III in mitochondrial fractions obtained from human livers genotyped for WT, Het or Mut CPOX in the presence or absence of 10μM Hg2+.

DISCUSSION

Several important observations are noted from these studies. Of primary interest is the finding that CPOX4 differs significantly from the wild-type enzyme in terms of physical stability and kinetic properties and, in particular, expresses only 50% the specific activity of the wild-type enzyme. These findings explain why CPOX4 is not likely to be etiologic in HCP, in which polymorphic forms of CPOX have been shown to express less than 10% of normal activity among carriers of fully homozygous CPOX mutations and approximately 50% among heterozygotes (Sassa et al., 1997; Rosipal et al., 1999; Wiman et al., 2002). These properties, however, are not without consequence in that they may predispose to compromised heme biosynthetic capacity in the presence of other mitigating factors, such as mercury exposure, that also impair this process. In this regard, when CPOX activity is expressed in terms of δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) equivalents, that is, nmol ALA/g tissue/unit time, the specific activity of the wild-type CPOX is four to seven times that of the rate limiting enzyme in heme biosynthesis, ALA synthetase, in most tissues (Woods, 1988). From the perspective of the present findings, a 50% loss of wild-type CPOX activity in the face of environmentally relevant cellular Hg concentrations would therefore not likely have a clinically significant impact on heme biosynthesis. In contrast, a 50% reduction in the fully mutant CPOX4 activity associated with equivalent Hg exposure could potentially compromise heme biosynthesis in tissue cells, possibly predisposing to disorders associated with heme deficiency by reducing activity to as much as 25% that of the wild-type enzyme. Notably, preliminary studies using Epstein Barr Virus transformed cells from CPOX wild-type and CPOX4 human donors suggest significantly diminished viability of transformed lymphocytes expressing CPOX4, compared with those expressing wild-type CPOX, following Hg2+ treatment (Li and Woods, 2009). Consistent with this finding, Chernova et al. (2007) demonstrated decreased viability and compromise of prosurvival signaling pathways both in cultured heme-deficient neuronal cells and in tissues of mice with genetically induced heme deficiency. These considerations may be relevant to observations of increased susceptibility to Hg-associated neurobehavioral and other neurological deficits among human CPOX4 carriers (Echeverria et al., 2006). Unlike polymorphisms that have been described in association with HCP, which are restricted largely to individual families, homozygous CPOX4 is prevalent among at least 2% of the general population (Woods et al., 2005).

A second point of interest from the present findings is the observation that Hg preferentially and perhaps selectively affects the second step of the oxidative decarboxylation reaction catalyzed by CPOX, resulting in accumulation of coproporphyrinogen as well as harderoporphyrinogen, the product of the first decarboxylation reaction. The mechanisms underlying this effect are not yet clear. Relevant to this issue, however, Lash et al. (1999) have proposed a model in which both decarboxylations of coproporphyrinogen occur at the same active site after a 90° anticlockwise rotation of harderoporphyrinogen. Several structural regions of the enzyme have been identified that confer ionic and steric stability for substrate utilization such that, under normal physiological circumstances, harderoporphyrinogen does not leave the enzyme cleft during the catalytic reaction. Hg binding to any of the thiol groups of the enzyme, in particular C319 (Fig. 6), could interfere with these structural requirements in such as way as to impair harderoporphyrinogen utilization and facilitate its release. Additionally, Nordmann et al. (1983) have reported that coproporphyrinogen competitively inhibits the use of harderoporphyrinogen as substrate and, moreover, that the oxidized product, coproporphyrin III, competitively inhibits the decarboxylation of both copro- and harderoporphyrinogens. In this regard, Hg2+ both promotes coproporphyrinogen accumulation (Woods and Southern, 1989) and accelerates its oxidation to coproporphyrin (Woods et al., 1990a,b) possibly promoting the observed harderoporphyrinogen accumulation. Whereas Hg2+ appears to inhibit both CPOX and CPOX4 activities with equal affinity, the consequences of equivalent concentrations of Hg2+ are more pronounced on protoporphyrinogen production by CPOX4 owing to its compromised substrate kinetics compared with those of the wild-type enzyme, that is, proportionately more coproporphyrinogen would accumulate and, hence, inhibit harderoporphyrinogen decarboxylation.

The striking consistency in biochemical properties observed between the recombinant forms of CPOX and the comparable forms in human livers with wild-type or mutant genotypes lends support to previous findings (Echeverria et al., 2006; Woods et al., 2005) that CPOX4 affects susceptibility to the porphyrinogenic and neurological effects of Hg exposure in humans. However, inasmuch as CPOX4 does not differ significantly from the wild-type CPOX in terms of susceptibility to inhibition by Hg2+ in vitro, we conclude that CPOX4 does not likely modify the kinetics of Hg retention and/or clearance in human subjects as a mechanistic basis of this effect. More intriguing is the likelihood that Hg exacerbates the potential limiting effects of CPOX4 on cellular heme availability, increasing the risks of adverse sequelae known to be associated with heme deficiency (Atamna et al., 2002). Studies to evaluate these possibilities in adults and children are currently in progress.

In conclusion, the present studies evaluated the biochemical and kinetic properties of CPOX4, the product of a polymorphism of the human CPOX gene that modifies the effects of mercury on neurobehavioral functions in humans. The findings suggest that CPOX4 may predispose to impaired heme biosynthesis, which is limited further by Hg exposure. These effects may underlie increased susceptibility to neurological deficits observed in Hg-exposed humans with CPOX4.

FUNDING

Center Grant (P30ES07033); Superfund Program Project Grant (P42ES04696) to the University of Washington from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health; and Wallace Research Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Bernard Grandchamp, INSERM U656, and Centre Francais des Porphyries, Universite Paris VII, Hopital Louis Morier, Colombes, France, for providing CPOX cDNA-pGEX-2T expression construct and University of Washington School of Pharmacy human tissue bank and the St. Jude Children's Hospital liver bank (Memphis, TN) for human liver samples.

References

- Atamna H, Killilea DW, Killilea AN, Ames BN. Heme deficiency may be a factor in the mitochondrial and neuronal decay of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:14807–14812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192585799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers MA, Aicher LD, Davis HA, Woods JS. Quantitative determination of porphyrins in rat and human urine and evaluation of urinary porphyrin profiles during mercury and lead exposures. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1992;120:272–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernova T, Steinert JR, Guerin CJ, Nicotera P, Forsythe ID, Smith AG. Neurite degeneration induced by heme deficiency mediated via inhibition of NMDA receptor-dependent extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:8475–8485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0792-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfau-Larue MH, Martasek P, Grandchamp B. Coproporphyrinogen oxidase: Gene organization and description of a mutation leading to exon 6 skipping. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:1325–1330. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.8.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria D, Woods JS, Heyer NJ, Rohlman D, Farin FM, Li T, Garabedian CE. The association between a genetic polymorphism of coproporphyrinogen oxidase, dental mercury exposure and neurobehavioral response in humans. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2006;28:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Evans JO. Evidence that the coproporphyrinogen oxidase activity of rat liver is situated in the intermembrane space of mitochondria. Biochem. J. 1978;172:345–347. doi: 10.1042/bj1720345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Evans JO, Jackson JR, Jackson AH. Factors determining the sequence of oxidative decarboxylation of the 2- and 4-propionate substituents of coproporphyrinogen III by coproporphyrinogen oxidase in rat liver. Biochem. J. 1978;169:215–223. doi: 10.1042/bj1690215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandchamp B, Phung N, Nordmann Y. The mitochondrial localization of coproporphyrinogen III oxidase. Biochem. J. 1978;176:97–102. doi: 10.1042/bj1760097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy GY, Jackson AH, Kenner GW, Suckling CJ. Isolation, structure and synthesis of a tricarboxylic porphyrin from the harderian glands of the rat. FEBS Lett. 1970;6:9–12. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash TD, Mani UN, Drinan MA, Zhen C, Hall T, Jones MA. Normal and abnormal heme biosynthesis 1. Synthesis and metabolism of di- and monocarboxylic porphyrinogens related to coproporphyrinogen-III and harderoporphyrinogen: A model for the active site of coproporphyrinogen oxidase. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:464–477. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DS, Flachsova E, Bodnarova M, Demeler B, Martasek P, Raman CS. Structural basis of hereditary coproporphyria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:14232–14237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506557102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Woods JS. Genotype determines susceptibility to mercury toxicity: Studies in transformed cells expressing coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX) and its genetic variant CPOX4. Toxicologist. 2009;108:289. [Google Scholar]

- Martasek P, Camadro JM, Delfau-Larue MH, Dumas JB, Montagne JJ, de Verneuil H, Labbe P, Grandchamps B. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and functional expression of a cDNA encoding human coproporphyrinogen oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994a;91:3024–3028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martasek P, Nordmann Y, Grandchamp B. Homozygous hereditary coproporphyria caused by an arginine to tryptophane substitution in coproporphyrinogen oxidase and common intragenic polymorphisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994b;3:477–480. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann Y, Grandchamp B, de Verneuil H, Phung L. Harderoporphyria: A variant hereditary coproporphyria. J. Clin. Invest. 1983;72:1139–1149. doi: 10.1172/JCI111039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosipal R, Lamoril J, Puy H, Da Silva V, Gouya L, Rooji FWM, Te Velde K, Nordmann Y, Martasek P, Deybach JC. Systematic analysis of coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene defects in hereditary coproporphyria and mutation update. Hum. Mutat. 1999;13:44–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:1<44::AID-HUMU5>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa S, Kindo M, Taketani S, Nomura N, Furuyama K, Akagi R, Nagai T, Terajima M, Galbraith RA, Fujita H. Molecular defects of the coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene in hereditary coproporphyria. Cell. Mol. Biol. 1997;43:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susa S, Daimon M, Ono H, Li S, Yoshida T, Kato T. The long, but not the short, presequence of human coproporphyrinogen oxidase is essential for its import and sorting to mitochondria. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2003;200:39–45. doi: 10.1620/tjem.200.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketani S, Kohno H, Furukawa T, Yoshinaga T, Tokunaga R. Molecular cloning, sequencing and expression of cDNA encoding human coproporphyrinogen oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1183:547–549. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiman A, Floderus Y, Harper P. Two novel mutations and coexistence of the 991C>T and the 1339C>T mutation on a single allele in the coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene in Swedish patients with hereditary coproporphyria. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;47:407–412. doi: 10.1007/s100380200059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS. Regulation of porphyrin and heme metabolism in the kidney. Semin. Hematol. 1988;25:336–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS, Bowers MA, Davis HA. Urinary porphyrin profiles as biomarkers of trace metal exposure and toxicity: Studies on urinary porphyrin excretion patterns in rats during prolonged exposure to methyl mercury. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1991;110:464–476. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90047-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS, Calas CA, Aicher LD. Stimulation of porphyrinogen oxidation by mercuric ion. II. Promotion of oxidation from the interaction of mercuric ion, glutathione, and mitochondria-generated hydrogen peroxide. Mol. Pharmacol. 1990a;38:261–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS, Calas CA, Aicher LD, Robinson BH, Mailer C. Stimulation of porphyrinogen oxidation by mercuric ion. I. Evidence of free radical formation in the presence of thiols and hydrogen peroxide. Mol. Pharmacol. 1990b;38:253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS, Echeverria D, Heyer NJ, Simmonds PL, Wilkerson J, Farin FM. The association between genetic polymorphisms of coproporphyrinogen oxidase and an atypical porphyrinogenic response to mercury exposure in humans. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005;206:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS, Fowler BA. Metal alteration of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and coproporphyrinogen oxidase. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;514:55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb48761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS, Martin MD, Naleway CA, Echeverria D. Urinary porphyrin profiles as a biomarker of mercury exposure: Studies on dentists with occupational exposure to mercury vapor. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 1993;40:235–246. doi: 10.1080/15287399309531791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods JS, Southern MR. Studies on the etiology of trace metal-induced porphyria: Effects of porphyrinogenic metals on coproporphyrinogen oxidase in rat liver and kidney. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1989;97:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(89)90067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga T, Sano S. Coproporphyrinogen oxidase. II. Reaction mechanism and role of tyrosine residues on the activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:4727–4731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]