Abstract

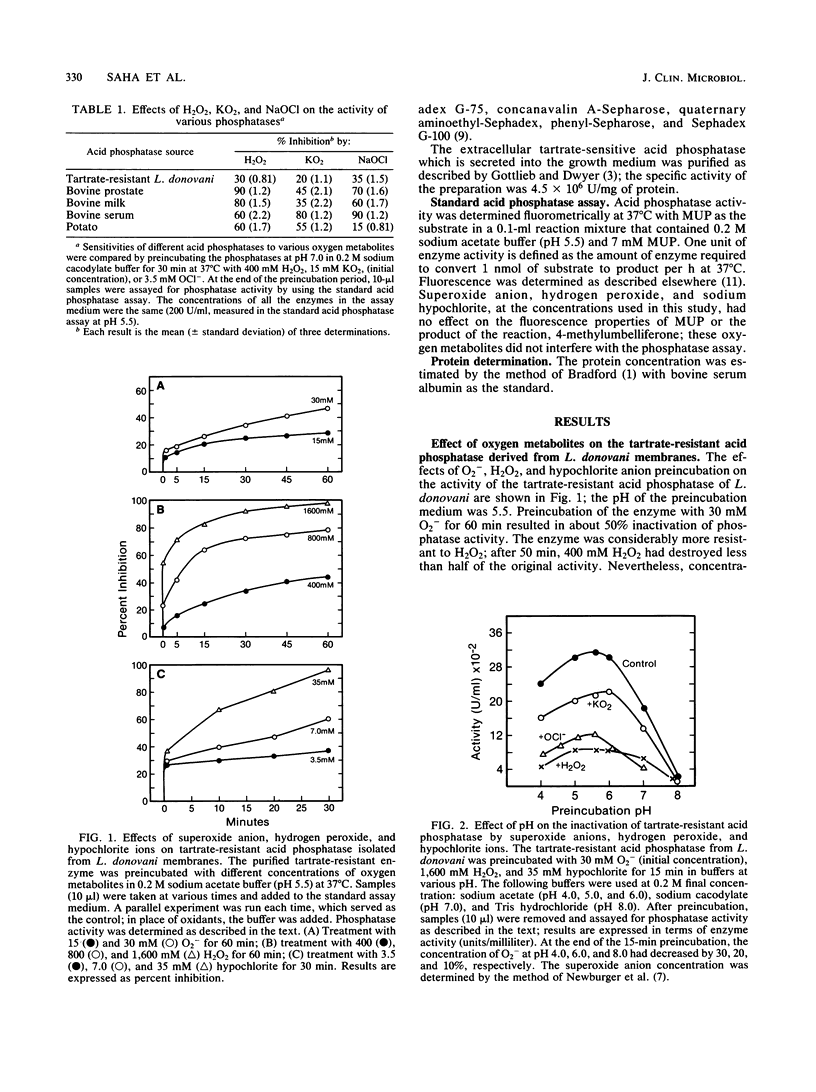

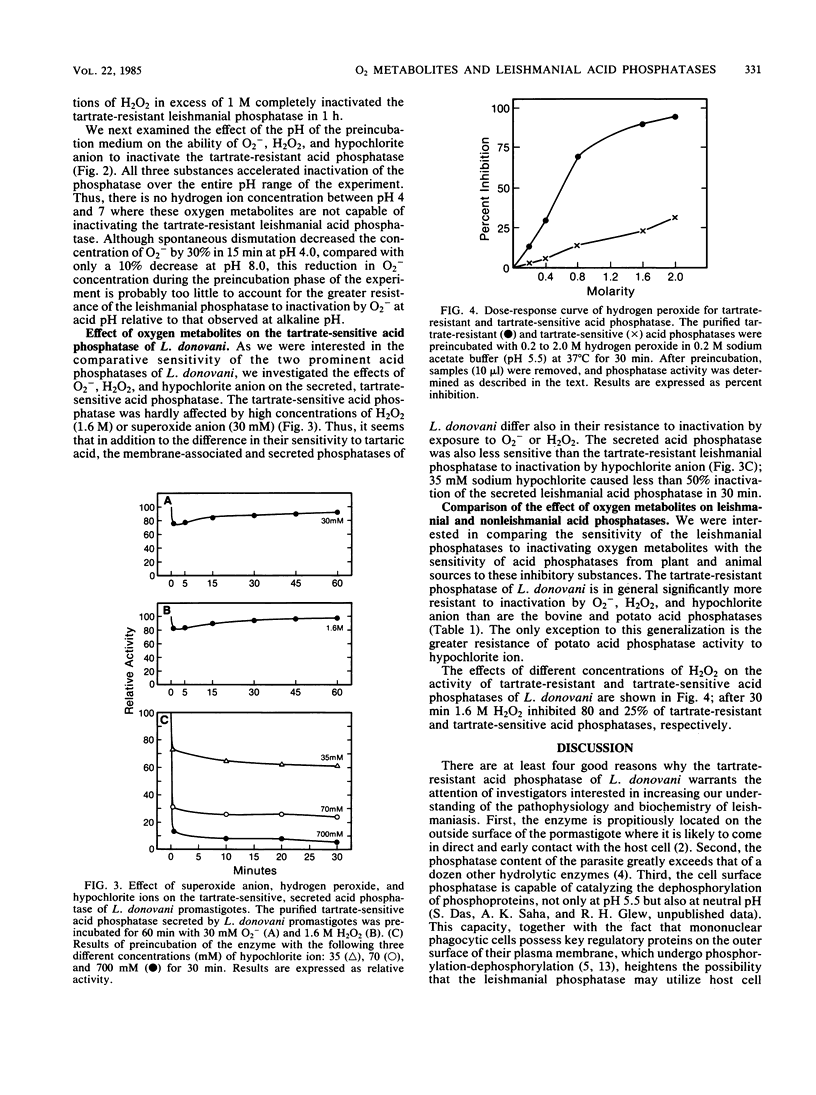

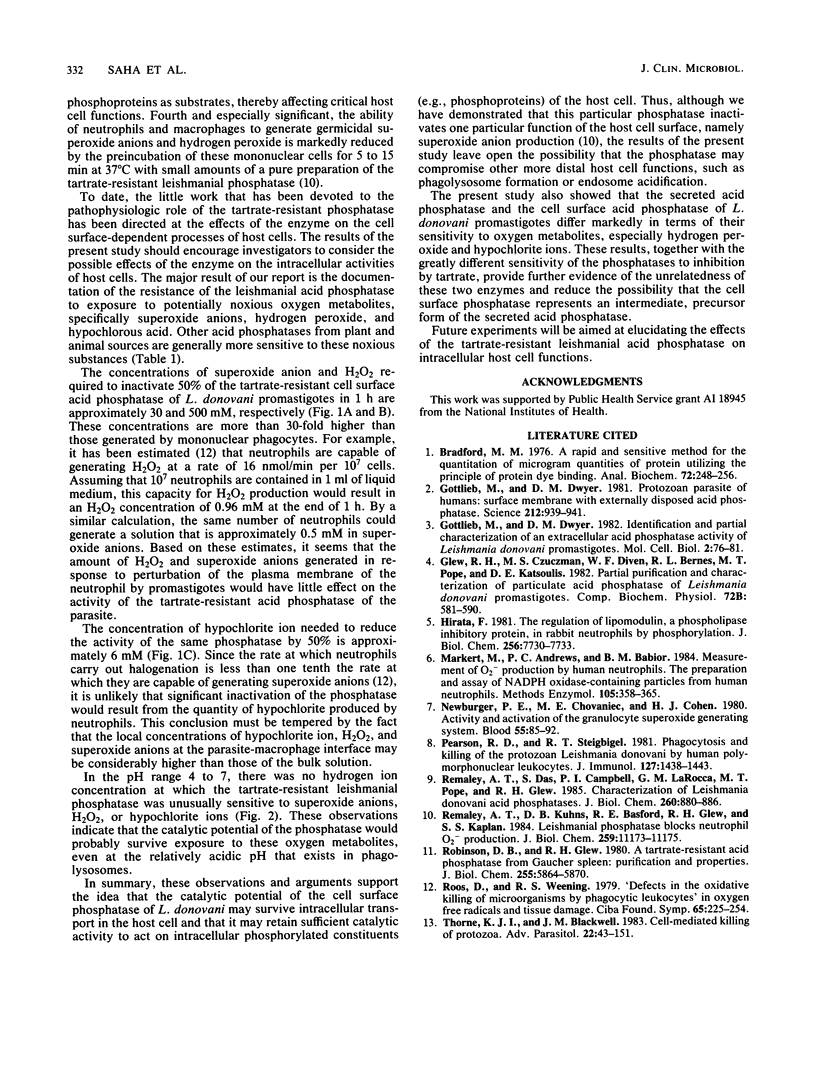

Leishmania donovani promastigotes produce large quantities of two distinct acid phosphatases; a tartrate-resistant enzyme is localized to the external surface of the plasma membrane, and a tartrate-sensitive enzyme is secreted into the growth medium. It was shown previously that preincubation of human neutrophils and macrophages with the tartrate-resistant phosphatase markedly reduced the ability of these host cells to produce superoxide anions in response to stimulation with the activator formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine. The possibility that the cell surface acid phosphatase or the phosphatase that is secreted into the extracellular fluid might compromise other host cell functions, especially intracellular ones, depends on the ability of the enzyme to resist exposure to toxic oxygen metabolites (e.g., superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, hypochlorite) generated by phagocytic cells. In the present report, we show that both leishmanial acid phosphatases were relatively resistant to inactivation by oxygen metabolites. At pH 5.5, the activity of the tartrate-resistant phosphatase was reduced 50% by incubation for 1 h with each of the following: 30 mM O2-, 500 mM hydrogen peroxide, and 6 mM hypochlorite ion. These concentrations are many fold greater than the concentrations of these substances that are generated by stimulated polymorphonuclear phagocytes. The tartrate-sensitive acid phosphatase differed markedly from the tartrate-resistant phosphatase in that the former was essentially insensitive to even very high concentrations of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide. Furthermore, 50% inactivation of the tartrate-sensitive leishmanial phosphatase required exposure to 35 mM hypochlorite for 30 min. These results indicate that the catalytic potential of these two leishmanial acid phosphatases probably survives exposure to toxic oxygen metabolites generated by neutrophils and macrophages.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glew R. H., Czuczman M. S., Diven W. F., Berens R. L., Pope M. T., Katsoulis D. E. Partial purification and characterization of particulate acid phosphatase of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1982;72(4):581–590. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(82)90510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb M., Dwyer D. M. Identification and partial characterization of an extracellular acid phosphatase activity of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Jan;2(1):76–81. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb M., Dwyer D. M. Protozoan parasite of humans: surface membrane with externally disposed acid phosphatase. Science. 1981 May 22;212(4497):939–941. doi: 10.1126/science.7233189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata F. The regulation of lipomodulin, a phospholipase inhibitory protein, in rabbit neutrophils by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1981 Aug 10;256(15):7730–7733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert M., Andrews P. C., Babior B. M. Measurement of O2- production by human neutrophils. The preparation and assay of NADPH oxidase-containing particles from human neutrophils. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:358–365. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newburger P. E., Chovaniec M. E., Cohen H. J. Activity and activation of the granulocyte superoxide-generating system. Blood. 1980 Jan;55(1):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R. D., Steigbigel R. T. Phagocytosis and killing of the protozoan Leishmania donovani by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Immunol. 1981 Oct;127(4):1438–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remaley A. T., Das S., Campbell P. I., LaRocca G. M., Pope M. T., Glew R. H. Characterization of Leishmania donovani acid phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 1985 Jan 25;260(2):880–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remaley A. T., Kuhns D. B., Basford R. E., Glew R. H., Kaplan S. S. Leishmanial phosphatase blocks neutrophil O-2 production. J Biol Chem. 1984 Sep 25;259(18):11173–11175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. B., Glew R. H. A tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase from Gaucher spleen. Purification and properties. J Biol Chem. 1980 Jun 25;255(12):5864–5870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos D., Weening R. S. Defects in the oxidative killing of microorganisms by phagocytic leukocytes. Ciba Found Symp. 1978 Jun 6;(65):225–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne K. J., Blackwell J. M. Cell-mediated killing of protozoa. Adv Parasitol. 1983;22:43–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]