Abstract

There are now several scientific studies that relate this traditional dietary pattern with the incidence of coronary heart disease, various types of cancer, and other diseases. The past years have several observational and clinical studies suggested the mechanisms by which this traditional diet may affect coronary risk. This review underlines the importance of the Mediterranean dietary patterns in the prevention of coronary heart disease.

Keywords: Mediterranean diet, risk, coronary heart disease, elderly

Mediterranean diet and health: epidemiological evidence

Epidemiological data have provided evidence that something unusual has been favorably affecting the health status of Mediterranean populations. Although private and state healthcare for many of these populations are inferior compared with those of northern Europe and North America, and the prevalence of smoking is high, the mortality rates in Mediterranean regions are lower than those of other countries. Mediterranean populations—Greeks and Italians in particular—have been reported to have among the highest life expectancies and the lowest incidence rates of all-cause mortality.

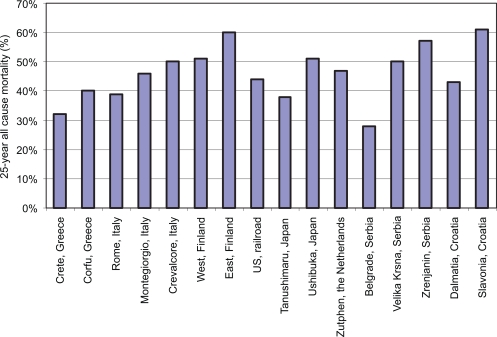

Figure 1 illustrates the 25-year all-cause mortality rates from 16 cohorts of the Seven Countries Study: the two Greek and three Italian cohorts have among the lowest mortality rates from all causes compared with the European and US cohorts of the study. Interpretations of these data are beset by difficulties. However, it seems that widespread factors including diet as well as physical activity and climate should be held responsible for these mortality rates.

Figure 1.

25-year all cause mortality from the Seven Countries Studies cohorts (adopted from Toshima H et al.).

Obesity is presently recognized as a public health problem. We have not achieved a consensus on what our next steps should be. I believe that effective communication and consumer research must become high priorities. For example, the language used to engage our patients and the public remains uncertain. As Wadden and Didie (2003) have shown, obese Caucasian and African American patients in Philadelphia prefer the use of the terms “weight”, and “excess weight”, rather than the terms “fat”, or “obese”. Whether these groups elsewhere in the United States or other ethnic groups prefer similar terms remains uncertain. It is equally likely that the terms “better nutrition” and “physical activity” rather than the terms “diet” and “exercise” are more likely to engage patients and the public. Although the medical and public health communities understand the linkages between obesity and other chronic diseases, these linkages are not widely understood by the general public, perhaps in part because our definition of obesity (body mass index [BMI] >30) is not viewed as a credible health risk by the public. Emphases on the relationship of obesity to erectile dysfunction may capture more attention and increased readiness to change.

Proven strategies have been identified and policy and environmental changes necessary to implement them are being put in place. Evidence-based strategies to increase physical activity have been published as a chapter for the Guide for Community Preventive Services, and a chapter on obesity that recommends combined nutrition and physical activity strategies for weight control in medical and worksite settings is almost complete. Reasonable scientific certainty exists with respect to the impact of television on obesity, viewing, and perhaps screen time, and breastfeeding. Increased fruit and vegetable intake, reduced soft drink intake, and reduced portion size are promising strategies. Although less evidence is available with respect to their impact on obesity, logical mechanisms link each of these to obesity. None of these strategies are likely to have an adverse effect on health. Furthermore, increased fruit and vegetable intake has other important health benefits that justify their promotion. The urgency of the epidemic and the lack of adverse effects suggest that we should actively promote these strategies in a variety of settings to assure that the public gets the message from multiple sources. In addition, as these strategies are implemented, we need to evaluate their impact. As Larry Green has said “… to develop better evidence-based practice we need practice-based evidence”.

The final general approach should be based on the costs of obesity and the cost-effectiveness of prevention and treatment. As medical costs rise, these costs are increasingly shifted to employees, and the cost-benefit of prevention becomes increasingly attractive. However, a major barrier is that the medical system does not reward preventive care, and medical insurance provides few incentives for patients to invest in healthful behaviors.

Mediterranean diet and coronary heart disease

According to the World Health Organization, the standardized cardiovascular mortality rates vary considerably between northern and southern European populations. Moreover, results from the 25-year follow-up of the Seven Countries Study (Toshima et al 1994) indicate that the prevalence of cardiovascular disease varied from 2%–10% in southern European countries and from 10%–18% in northern European countries. The investigators attributed the differences in mortality rates between the 16 cohorts to the nutritional habits of the participants and, in particular, to the intake of saturated fatty acids and flavonoids.

Investigators from the Lyon Heart Study (de Lorgeril et al 1999) examining 605 patients aged 55–80 years with previous myocardial infarction found that the benefits of the Mediterranean diet extended to the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Those who followed the Mediterranean diet had 50%–70% lower risk of recurrent heart disease compared with those who followed a diet similar to the American Heart Association (AHA) Step–I diet. Their findings illustrate the potential importance of the Mediterranean dietary pattern compared with other recommended diets, within the context of a Step–I (ie, total fat <30% of total calories, carbohydrates >55% of total calories, protein about 15% of total calories and cholesterol <300 mg/dl).

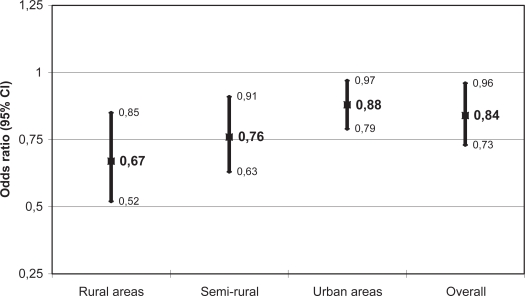

The CARDIO2000 investigators (Panagiotakos et al 2002) studied a sample of 848 middle-aged and older patients with previous myocardial infarction and unstable angina and 1078 age- and sex- matched controls from several Greek regions. It was found that adoption of a Mediterranean diet was associated with an adjusted 23% rate reduction in the risk of developing a first event of acute coronary syndrome. However, the effect of this traditional diet on coronary risk varied considerably among Greek areas. In particular, the benefits from the adoption of the Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular disease risk seemed more prominent in people who were living in rural areas as compared with subjects living in urban or semi-rural areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The adjusted effect of the adoption of Mediterranean diet on the risk of developing acute coronary syndromes, by type of region (Panagiotakos et al. 2002).

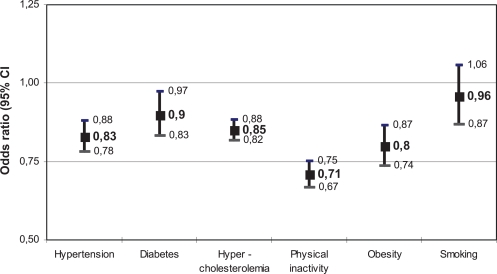

When the CARDIO2000 investigators focused their interest on hypercholesterolemic patients (Pitsavos et al 2002) they observed a synergistic effect of the combination of the Mediterranean diet with statin treatment on coronary risk. In particular, they observed that the aforementioned combination was associated with a 43% reduction in coronary risk, independently from cholesterol levels and other cardiovascular factors. Further analysis from the same study in hypertensive patients revealed that the adoption of the Mediterranean diet was associated with a 17% reduction in the coronary risk in controlled hypertensive subjects, with an 8% reduction in unaware, with a 7% reduction in acknowledged but uncontrolled diet and with a 20% reduction in normotensive subjects. Further analysis showed that the adoption of the Mediterranean diet was associated with a reduction of the risk of developing acute coronary syndromes in diabetic, physically inactive, and obese subjects. On the contrary, the Mediterranean diet did not show any significant influence on coronary risk in current smokers (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The adjusted, for the conventional risk factors, effect of the Mediterranean diet on the risk of developing acute coronary syndromes, in hypertensive, hypercholesterolemic, diabetes, physically inactive, obsess, and smokers’ subjects (Panagiotakos et al. 2002).

In the ATTICA study of 3042 adult men and women from Greece (Pitsavos et al 2003), investigators observed that participants with high blood pressure were less likely to consume the traditional Mediterranean diet compared with normotensives (35% vs 64%, p = 0.02). The consumption of a Mediterranean diet was associated with a 26% lower relative risk of being hypertensive after adjusting for demographic, clinical, and lifestyle variables. Additionally, well controlled hypertensive patients consumed a Mediterranean diet more frequently than treated, but uncontrolled, hypertensives. Thus, the consumption of the Mediterranean diet was related to a 27% lower relative risk of having uncontrolled hypertension.

Recently a prospective study involving 22,043 adults from Greece (Trichopoulou et al 2003) found an inverse association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and death from coronary heart disease. In particular, approximately a 20% increment in the Mediterranean diet score (adherence to diet was assessed by a 9-point Mediterranean diet scale) was associated with a 33% reduction in coronary heart disease mortality. These associations were present irrespective of sex, smoking status, level of education, BMI, and physical activity. This is significant among participants 55 years of age or older, but not among younger participants. This age-specific association might reflect the effects of a cumulative exposure to a more healthy diet (ie, the Mediterranean diet). In a review paper, Trichopoulou and colleagues (1995) concluded that the Mediterranean diet is positively associated with longevity among the elderly, and therefore the traditional Mediterranean diet represents a healthy nutritional pattern. Kouris-Blazos and colleagues (1999), studying 141 Anglo Celts and 189 Greek-Australian subjects of both sexes aged >70 years, concluded that a diet that adhered to the principles of the traditional Mediterranean diet was associated with a longer survival irrespective of their origin. Furthermore, Trichopoulou and colleagues (2001), in one of the few studies that assessed Mediterranean diet and longevity among elderly Greeks, observed that a one unit increase in diet score, devised a priori on the basis of eight component characteristics of the traditional common diet in the Mediterranean region, was associated with a significant 17% reduction in overall mortality.

The investigators of Healthy Ageing (a longitudinal study in Europe: HALE) observed that adherence to a Mediterranean diet was associated with 23% lower risk of death, while moderate alcohol use was associated with a 22% reduction of the previous risk (Knoops et al 2004). The “Habits in Later Life Only” study showed that only legumes intake was associated with a reduction in mortality hazard ratio, after adjustment for location/ethnicity of 785 elderly people from Japan, Sweden, Australia, and Greece. In accord to the previous studies, we found that greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with 21% lower odds of having one additional risk factor (ie, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, obesity) in women and with 14% lower odds in men, irrespective of various potential confounders. This finding may be directly linked to the reduction of cardiovascular risk and consequently prolong life span.

Furthermore, Trichopoulou and colleagues (2003) suggest that elements of the traditional Mediterranean diet found in other cultures using different food options (other than olive oil) for increasing intake of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats lead to similar effects in the healthy status of its population.

Table 1 summarizes the findings from several observation studies and clinical trials that evaluated the effect of the Mediterranean diet on coronary heart disease risk.

Table 1.

Summary of studies assessing effect of Mediterranean diet on coronary heart disease

| Study | Population | Type of study | Outcome | Effect measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Lorgeril et al | 303 with AMI, 302 controls | Randomized prospective case-control trial | Second event of CHD | 0.27; 0.12–0.59 |

| Panagiotakos et al | 661 with ACS, 661 controls | Case-control | First event of ACS | 0.84; 0.73–0.96 |

| Pitsavos et al | 534 with ACS, 399 controls with hypercholesterolemia | Case-control | First event of ACS | 0.88; 0.82–0.94 |

| Pitsavos et al | 418 with ACS, 303 controls with hypertension | Case-control | First event of ACS | 0.92; 0.85–0.98 |

| Trichopoulou et al | 22,034 adult men and women | Population-based prospective | Fatal CHD | 0.67; 0.47–0.94 |

| Martinez-Gonzalez et al | 171 with AMI, 171 controls | Case-control | First event of AMI | 0.55; 0.42–0.73 |

| Pitsavos et al | 307 with ACS, 198 controls with metabolic syndrome | Case-control | First event of ACS | 0.64; 0.44–0.95 |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CHD, coronary heart disease.

A pathophysiological explanation

The Mediterranean diet is high in monounsaturated fat, principally olive oil, low in saturated fat, high in complex carbohydrates from legumes, and high in fiber, mostly from vegetables and fruits. Total fat may be high (approximately 40% of total energy intake), and the monounsaturated-to-saturated fat ratio should be around 2. The high content of vegetables, fresh fruits, cereals, and olive oil guarantees a high intake of beta-carotene, vitamins C and E, polyphenols, and various important minerals. These key elements have been suggested to be responsible for the beneficial effect of the diet on human health and especially on cardiovascular disease.

The Seven Countries Study of 12,763 middle-aged men from 16 cohorts around the world (Keys et al 1986; Toshima et al 1994) reported that the protective role of the Mediterranean diet against atherosclerosis can be partially attributed to the reduction of blood pressure levels. Many researchers recently have associated the Mediterranean diet with improvements in blood lipid profile (especially low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides), decreased oxidation of lipids, and decreased risk of thrombosis (ie, fibrinogen levels) all changes meaning improvement in endothelial function.

There is growing evidence that protective health benefits are offered by diets high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains that include fish, nuts, and low-fat dairy products. The traditional Mediterranean diet, of which olive oil is the principal source of fat, encompasses these dietary characteristics. In the past few decades, a large body of evidence has found associations between the Mediterranean diet and all-cause mortality, incidence of coronary heart disease, and various types of cancer. In this article, results from studies that have related the Mediterranean diet to a lower coronary heart disease risk, especially in the elderly, will be reviewed.

Additional characteristics of the traditional mediterranean diet

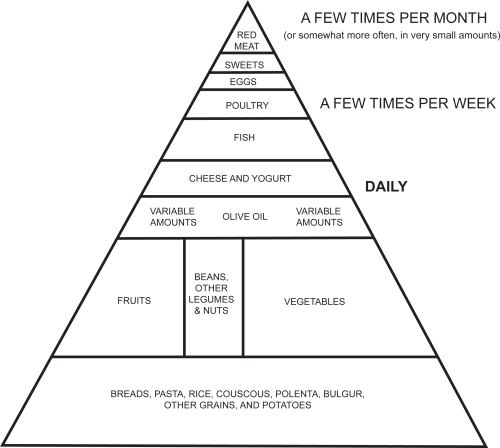

The traditional “Mediterranean diet” refers to specific food consumption patterns typical of some Mediterranean regions in the early 1960s, such as Crete, other parts of Greece, Spain, and southern Italy. In general, the traditional Mediterranean diet is characterized by a diet high in fruits, vegetables, cereals, potatoes, poultry, beans, nuts, lean fish, dairy products, small quantities of red meat, moderate alcohol consumption, and olive oil as an important fat source. In particular, this dietary pattern consists of agents, as follows:

Daily consumption: non-refined cereals and products (whole grain bread, pasta, brown rice, etc), vegetables (2–3 servings/day), fruits (6 servings/day), olive oil (as the main added lipid) and dairy products (1–2 servings/day):

Weekly consumption: fish (4–5 servings/week), poultry (3–4 servings/week), olives, pulses, and nuts (3 servings/week), potatoes, eggs, and sweets (3–4 servings/week):

Monthly consumption: red meat and meat products (4–5 servings/month).

The Mediterranean diet also is characterized by moderate consumption of red or white wine (ie, more than 100–200 mL per day) and almost always during meals. Although the intake of milk is moderate, the consumption of cheese and yogurt is high. Feta cheese is added regularly to salads and to accompany vegetable stews. This traditional dietary pattern is illustrated in a diet-pyramid (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The traditional Mediterranean diet pyramid (created according to http://oldwayspt.org/index, accessed on February 5, 2007).

This diet is low in saturated fat (≤7%–8% of energy daily), with total fat ranging from <25% to >35% of daily requirements from one geographical area to another. The high monounsaturated to saturated fat ratio is greater than two. It is difficult to define the Mediterranean diet, given the broad geographical regions involved. Each one of these countries uses different dietary compositions, precluding a single definition of the Mediterranean-style diet. For example, the Italian variant of the Mediterranean diet is characterized by higher consumption of pasta, whereas fish consumption is particularly high in Spain. In Greece, diets include large quantities of whole grain bread, cooked foods, as well as salads rich in olive oil, and in which vegetables and legumes are consumed in large amounts. Nevertheless, in all instances the ratio of monounsaturated to saturated lipids is much higher than in Northern Europe and North American diets.

Discussion

Large cohort studies have shown that a high adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced blood pressure levels and markers of vascular inflammation. The beneficial effects on surrogate markers of cardiovascular risk add biological plausibility to the epidemiologic evidence that supports a protective effect of the Mediterranean diet. Olive oil, a rich source of monounsaturated fatty acids, is a main component of the Mediterranean diet. Virgin olive oil retains all the lipophilic components of the fruit, α-tocopherol, and phenolic compounds with strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. In addition, tree nuts, which are also typical in the Mediterranean diet, have a favorable fatty acid profile and are a rich source of nutrients and other bioactive compounds, which may beneficially influence the risk for CHD, such as fiber, phytosterols, folic acid, and antioxidants. Frequent nut intake has been associated with decreased CHD rates in prospective studies. Walnuts differ from all other nuts through their higher content of polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly α-linolenic acid, a plant n-3 fatty acid (Kouris-Blazos et al 1999), which may confer additional antiatherogenic properties.

Conclusion

Growing evidence indicates that the Mediterranean diet is beneficial to human health. Recent studies reveal that the cardioprotective effects of the Mediterranean diet are effective through various mechanisms. These findings render this dietary pattern extremely attractive for public health purposes, and should be adopted by almost everyone.

Footnotes

Disclosure

No competing financial interest has been declared.

References

- Assmann G, de Basker G, Bagnara S, et al. International consensus statement on olive oil and the Mediterranean diet—implications for health in Europe. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1997;6:418–21. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackberry L, Kouris-Blazos A, Wahlqvist ML, et al. Legumes: the most important dietary predictor of survival in older people of different ethnicities. Asia Pec J Ota Nutr. 2004;13:S126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, et al. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction. Final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99:779–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito K, Giugliano F, DiPalo C, et al. Effect of lifestyle changes on erectile dysfunction in obese men. JAMA. 2004;291:2978–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafatos A, Diacatou A, Voukiklaris G, et al. Heart disease risk-factor status and dietary changes in the Cretan population over the past 30 years: the Seven Countries Study. Am X Gin Nutr. 1997;65:1882–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.6.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A, Menotti A, Karvonen MJ, et al. The diet and 15-year death rate in the Seven Countries Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:903–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp HW. Dietary fatty acids in human thrombosis and hemostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:16878–985. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.5.1687S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoops KT, de Groot LC, Kromhout D, et al. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. JAMA. 2004;292:1433–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouris-Blazos A, Gnardellis C, Wahlqvist ML, et al. Are the advantages of the Mediterranean diet transferable to other populations? A cohort study in Melbourne, Australia. Br J Nutr. 1999;82:57–61. doi: 10.1017/s0007114599001129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris-Etherton P, Eckel R, Howard B, et al. Lyon Diet Heart Study. Benefits of a Mediterranean-style, National Education Program/AHA Step 1 Dietary Pattern on cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2001;103:1823–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Fernandez Jame B, Serrano-Martinet M, et al. Mediterranean diet and reduction in the risk of a first acute myocardial infarction: an operational healthy dietary score. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41:153–60. doi: 10.1007/s00394-002-0370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, Pitsavos C, et al. The association of Mediterranean diet with lower risk of acute coronary syndromes, in hypertensive subjects. Int J Cardiol. 2002;82:141–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(01)00611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, et al. The role of traditional Mediterranean-type of diet and lifestyle, in the development of acute coronary syndromes: preliminary results from CARDIO2000 study. Centr Eur J Public Health. 2002;10:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos CH, Chrysohoou C, et al. Status and management of hypertension in Greece; role of the adoption of a Mediterranean diet: the Attica study. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1483–9. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200308000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, et al. The adoption of Mediterranean diet attenuates the development of acute coronary syndromes in people with the metabolic syndrome. Nutr J. 2003;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, et al. The effect of Mediterranean diet on the risk of the development of acute coronary syndromes in hyperchotesterolemic people: a case-control study (CARDIO2000) Coron Artery Dis. 2002;13:295–300. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Chrysohoou C, Stefanadis C. Epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in Greece: aims, design and baseline characteristics of the ATTICA study. BMC Public Health. 2003;3:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-3-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruit-Gutierrez V, Muriana FJG, Guerrero A. Plasma lipids, erythrocyte membrane lipids and blood pressure of hypertensive women after ingestion of dietary oleic acid from two different sources. J Hypertens. 1996;14:1483–90. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199612000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strazullo P, Ferro-Luzzi A, Saini A, et al. Changing the Mediterranean diet: effects on blood pressure. J Hypertens. 1986;4:407–12. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessons from the Seven Countries Study. In: Toshima H, Koga Y, Blackburn H, editors; Dontas A, editor. CVD risk factor and trends in Greece. Tokyo: Springer Verlag; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2599–608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulou A, Kouris-Blazos A, Wahlqvist M, et al. Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ. 1995;311:1457–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7018.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P. In: The traditional Mediterranean diet constituents in health promotion. Matalas AL, Zampelas A, Stavrinos V, editors. Boca Raton, FL: The CRC Pr; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulou A. Traditional Mediterranean diet and longevity in the elderly: a review. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:943–7. doi: 10.1079/phn2004558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Didie E. What’s in a name? Patient’s preferred terms for describing obesity. Obesity Res. 2003;11:1140–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [WHO] World Health Organization Study Group . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Technical Report Series; 1990. Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases; p. 797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]