Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this paper is to delineate the underlying premises of the concept of engagement in persons with dementia and present a new theoretical framework of engagement.

Setting/Subjects:

The sample included 193 residents of 7 Maryland nursing homes. All participants had a diagnosis of dementia.

Methodology:

We describe a model of factors that affect engagement of persons with dementia. Moreover, we present the psychometric qualities of an assessment designed to capture the dimensions of engagement (OME, Observational Measurement of Engagement). Finally, we detail plans for future research as well as data analyses that are currently underway.

Discussion:

This paper lays the foundation for a new theoretical framework concerning the mechanisms of interactions between persons with cognitive impairment and environmental stimuli. Additionally, the study examines what factors are associated with interest and negative and positive feelings in engagement.

Keywords: Engagement, dementia, nursing home residents, person attributes, environment attributes, stimulus attributes

The concept of engagement has been documented in a range of settings, including the client-therapist relationship (1), providing intellectual tasks for students and professionals (2), and in studies of nursing home residents (3). Studies have shown that nursing home residents spend the majority of their time not engaged in any meaningful activity (3; 4; 5). Prolonged lack of stimulation can be particularly detrimental to persons in nursing homes who suffer from dementia, as it magnifies the apathy, boredom, depression, and loneliness that often accompany the progression of dementia (6; 7). Consequently, it is of critical importance that engagement of these residents becomes a priority within nursing facilities.

Engaging older persons with dementia in appropriate activities has been shown to yield beneficial effects such as increasing positive emotions, improving activities of daily living (ADL) and improving the quality of life (8; 9) developing constructive attitudes toward dementia among nursing staff members (10) and decreasing problem behaviors among nursing home populations (11).

The study of engagement is a necessary foundation for the development of nonpharmacological interventions for persons with dementia, whether the interventions address depression, agitation, apathy, loneliness, or boredom. The analysis of different forms of engagement of persons with dementia is expected to help such persons by reducing boredom and loneliness, and by increasing interest and positive emotions. It is also expected to help staff members by providing them with tools that they can utilize in caring for these persons. Although apathy, boredom, depression, and loneliness frequently accompany the progression of dementia, engagement of the demented nursing home residents in constructive, meaningful activities creates a possibility for enhancing the level of their daily functioning and for preventing the manifestation of loneliness, boredom, and the problem behaviors associated with dementia.

This paper delineates the underlying premises of the concept of engagement in persons with dementia and offers a literature review of some of the most illuminating studies to date on this topic. Additionally, we provide data on our preliminary studies of engagement and will detail plans and goals for continued research.

Definition and Literature Review

We define engagement as the act of being occupied or involved with an external stimulus. Although the concept of engagement of persons with dementia seems to be very important, only a few relevant studies have been published. Mayers and Griffin studied the responses of persons with Alzheimer's disease to the following stimuli – a plush dog, fabric book, a doll, toy metal cars, keys, busy box, and two types of transformers (i.e., plastic toys designed for children) (12). Five male Alzheimer's patients and four male patients with alcohol-related dementia were involved in the study. Each day, participants were presented with a different randomly chosen stimulus for a 10-minute interval. There were differences across study participants with respect to the duration of time they remained engaged with the different stimuli. For instance, patient A was more involved with one of the transformers (a mechanical toy) and with the plush dog than with the busy box and the other transformer. Patient B did not show any interest in either the transformer or plush dog, but engaged with a busy box. Overall duration of interest in objects ranged from around 300 seconds for cars and the busy box to about 40 seconds for the fabric book. The authors noted that “even play of 30 to 60 seconds duration represents a significant departure from the blank stare so typical of the demented patient.”

A study conducted by Buettner (13) utilized a program termed “Simple Pleasures.” The study investigated the effects of more than 30 handmade recreational items on the behavior of fifty-five nursing home residents with dementia. During the pilot phase, all stimuli were tested for safety, appeal, and therapeutic value. During the treatment phase, several assessments of the residents, their behavior and engagement, as well as the setting characteristics were implemented. To measure residents' cognitive status, the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) (14) and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (15) were used. The results of the study provided an interesting insight into the relation between item preferences (all items were presented at one time to the resident, who was observed while making a choice), residents' level of cognitive impairment, specifics of agitated behavior, and the average amount of time the item was used during the session. The greatest number of residents selected the tetherball. It was appealing to residents at all levels of cognitive impairment. At the same time, polar fleece hot water bottles and a wandering cart attracted a small number of the residents with low MMSE scores, although the duration of engagement with these items was the longest.

Differentiation between levels of engagement was the purpose of a study devoted to Montessori-based activities for long-term care residents and adult day care clients with advanced dementia (9). Comparison of the activities during regular and Montessori-based programming revealed a significant treatment effect. Specifically, persons involved in the treatment phase in both settings exhibited greater amounts of constructive engagement (motor or verbal behavior in response to the specific activity) and showed less passive engagement.

Most studies that deal with the analysis of problem behaviors do not directly address the phenomenon of engagement. However, it is implied that a stimulus that has resulted in decreased agitation must have produced engagement in order to affect change. Among the most frequently used stimuli in nonpharmacological interventions are music, structured activities, pet therapy, and simulated interactions.

Music

Music interventions are used to engage persons with dementia for two general purposes: as relaxation or as sensory stimulation. In using music for relaxation during bathing, two studies found that music was effective in reducing aggressive behaviors during bathing procedures and also showed a trend for decreasing other negative behaviors (16; 17). Of the three studies that examined the relaxing impact of quiet music during mealtime, two reported a significant decline in agitation during lunchtime (18; 19), and the third did not demonstrate an effect during dinner (20). Several studies reported a reduction in verbal agitation or agitation in general while listening to music on a tape or a CD player (21; 22; 23; 24).

Structured activities

Surprisingly, relatively little research was found concerning the impact of structured activities, although some combination therapies and music therapy include structured activities. A positive impact of activities is reported by Aronstein et al.(25), who presented 15 nursing home residents with several categories of recreational interventions including: manipulative (e.g., bead maze), nurturing (e.g., doll), sorting (e.g., puzzles), tactile (e.g., fabric book), sewing (lacing cards) and sound/music (e.g., melody bells) stimuli. Fourteen episodes of agitation were observed for five residents, and the interventions were judged as helpful in alleviating agitation in 57 percent of these episodes, although a study of group activities that was provided to three persons yielded inconclusive results (26).

Pet visits

Studies suggest a beneficial effect of interactions with pets. For 28 special care unit residents, half-hour sessions with a dog resulted in significantly lower levels of agitation than half-hour sessions with only the researcher present (27). In addition, the presence of a pet at home was related to a lower prevalence of verbal aggression in a study of 64 persons suffering from dementia (28).

Family videos

Videotapes of family members talking to nursing home residents and Simulated Presence therapy, which involves an audiotape of a relative's portion of a telephone conversation with a resident, were effective stimuli in reducing agitation (29; 30). In contrast, a generic videotape of reminiscence and relaxation did not result in a reduction in agitation (31).

The above studies show promise in the effect of stimuli to engage persons with dementia. These fall short, however, in offering guidance regarding engagement. In addition to methodological problems with many of the studies (32), many combine specific stimuli with varying amounts of social interaction with the therapist providing the stimuli. However, social interaction is also a very expensive stimulus in the context of the nursing home. For clinical purposes, it is vital for staff members to understand the engagement value of different stimuli and how to match stimuli to persons at times when the staff members are unavailable.

A conceptual framework of engagement

Our current approach to engagement of nursing home residents is modeled after the clinical situation found most often in nursing homes. Specifically, a nursing staff member notices that a person with dementia needs stimulation and contact but cannot provide these because of low staffing levels and an overload of other work requirements. This staff member has an urgent need for a relatively simple solution that will only minimally involve his or her time. Past research and clinical experience show that providing the aforementioned stimuli may have the potential to fulfill this need for some of the residents. Additional knowledge concerning this potential and what would make this a feasible solution could make a significant difference to both staff members and residents. It will also serve as a basis of knowledge upon which additional engagement studies can be built.

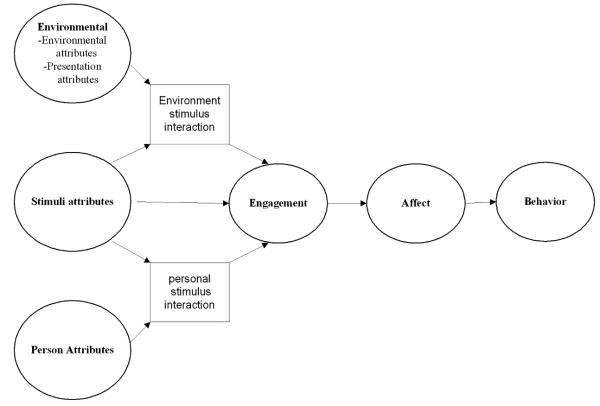

The theoretical framework we are proposing, the Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement, is summarized in Figure 1. It asserts that engagement with a stimulus is affected by environmental attributes, person attributes, and stimulus attributes. Engagement in turn results in a change in affect that influences the presentation of behavior problems. We will briefly review each of these constructs, with special emphasis on the construct of engagement.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework concerning engagement of persons with dementia

Environmental attributes

convey those elements in the person's environment that may influence the person's level of attention to the stimulus presented. Such attributes may capture the degree of likely interference with the stimulus and the degree to which the setting characteristics will be conducive to focusing on the stimulus. Specific environmental attributes which may be examined include the location in which the stimulus is presented, the number of people around, the level of temperature, noise, and light, the time of day of stimulus presentation as well as the manner of presentation (e.g., gradual, where the stimulus was discussed with and modeled for the participant, and abrupt, where the stimulus was simply given to the participant without any discussion or modeling).

Person attributes

Various characteristics of the person with dementia are likely to impact engagement with a stimulus. Most clearly, as cognitive function is related to ability to attend and to apathy, it is also related to level of engagement. Demographic characteristics may also relate to level of engagement, as can general level of activity and interest. Whether past interest in hobbies or in other aspects of daily living relates to current level of engagement (when controlling for cognitive level) needs to be examined.

Stimuli

There are tentative indications in the literature that persons suffering from dementia benefit from contact with pets and dolls. Additionally, clinical practice has shown variability among patients in level of engagement with stimuli in their environment. However, the mechanism underlying this has not been investigated. Thus, the stimulus attributes that may affect level of engagement are not yet known, but may include the degree to which the stimulus has social qualities, the degree to which it is manipulative, such as in the opportunity to arrange wooden blocks, or the degree to which it emulates a work role, like a task of folding towels or sorting envelopes.

Environment-stimulus interaction

It is likely that certain stimuli may be more affected by specific setting characteristics than others. Music, for example, is more likely to be affected by setting noise and less likely to be affected by modeling, whereas the reverse is likely to occur for blocks.

Person-stimulus interactions

Some stimuli may be more appropriate for certain people than others. One example of a person-stimulus interaction is the degree to which the person has shown a preference for this type of stimuli in the past, such as liking dogs premorbidly. Stimuli can also be chosen on the basis of a person's self-identity. Research on self-identity of persons with dementia has explored four role identities: family, work, hobbies, and attributes (32; 33). For family/social role, for example, family pictures or a family tree may be used as stimuli. For professional roles, participants may receive materials that relate to their previous vocation. For leisure time and hobbies roles, the stimuli may be listening to music they enjoyed, singing along with a tape, playing a musical instrument, or looking at travel magazines. For personal attributes and traits roles, a resident may examine achievements such as their degrees or awards, newspaper articles about family members, or may participate in activities that are presented as volunteering, such as stamping envelopes. Such person-tailored stimuli are likely to have a more potent effect on engagement than standard stimuli (11; 32; 33).

Other interactions

There may be a person-environment (e.g., a person who is more sensitive to noise or light levels) as well as 3-way interactions, and these should be investigated in future research.

The dimensions of engagement

In our model, engagement is conceptualized as consisting of 5 dimensions: 1) rate of refusal of the stimulus; 2) duration of time that the resident was occupied or involved with a stimulus 3) level of attention to the stimulus; 4) attitude toward the stimulus, and 5) the action towards the stimulus, such as holding it or talking to it, the target of the person's talk while engaged with the stimulus (e.g., the stimulus itself or another resident), and the content of the person's talk while engaged with the stimulus.

Procedures

Participants

This study was reviewed and approved by the IRB at the Charles E. Smith Life Communities. The sample included 193 residents of 7 Maryland nursing homes. Informed consent was obtained for all study participants from their relatives or other responsible parties. Additional information on the informed consent process is available elsewhere (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 1988). Our main criterion for inclusion was a diagnosis of dementia (derived from either the medical chart or the attending physician). The criteria for exclusion were:

○ The resident had an accompanying diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

○ The resident had no dexterity movement in either hand.

○ The resident could not be seated in a chair or wheelchair.

○ The resident was blind or deaf.

○ The resident was younger than 60 years of age.

Once consent was obtained for eligible participants, background information was gathered from each participant's chart in the nursing home. In addition, the MMSE was administered to each participant. Those who received MMSE scores greater than 23 were dropped from the study, as persons with a comparatively higher level of cognitive functioning are usually able to articulate their interests and needs.

In our study, 151 participants were female (78%), and age averaged 86 years (SD 7.5, ranging from 60 to 101 years). The majority of participants were Caucasian (81%), and most were widowed (65%). ADL performance, which was obtained through the Minimum Data Set [30], averaged 3.6 (SD 1.0, range 1-5; Scale: 1- ‘independent’ to 5- ‘complete dependence’). Cognitive functioning, as assessed via the Mini-Mental State Examination (14), averaged 7.2 (SD 6.3, range 0-23). Participants had an average of 6.7 medical diagnoses (SD 2.6, ranging from 2 to 18). Very few (1.1%) participants had no schooling, 16.6% had completed 11th grade or less, 45% had completed high school, 12.2% had completed either some college or a technical or trade school and 25% had earned a Bachelor's degree or higher. Participants worked in a wide variety of occupations, with the most common being homemaker (20.2%), business (17.1%), clerk/secretaries (16.1%), health field work (9.3%), education (7.3%), and government (5.2%). Fewer than 5% worked in the following occupations: industry; human services; law; armed forces (Military/Army/Navy); art; retired; general services (e.g. house cleaner); agriculture; science; and other fields.

We included 24 stimuli, chosen on the basis of their ability to elucidate factors that may affect engagement, and on the basis of discussions with research and clinical personnel who have been engaging nursing home residents over the past several years. The stimuli were chosen to demonstrate different levels on dimensions that could affect engagement, including being life like or artificial, social vs. nonsocial, manipulative vs. passive, work- related vs. not work, and having a personal meaning vs. being general. We are currently analyzing the effects of these dimensions. The stimuli were: a life-like doll, a plush animal, a childish doll, an expanding sphere, music, a tetherball, a squeeze ball, a large print magazine, a fabric book, a respite video, a wallet/purse, an activity pillow, stamping envelopes, coloring with markers, towels to fold, flower arrangement, building blocks, a robotic animal, a sorting task, a puzzle, a real baby, a real pet, and 2 stimuli personalized for each resident on the basis of past and present interests. The personalized stimuli were designed after identifying the most important identity or preference in the participant's life, both past and present through the Self-Identity Questionnaire (32). This questionnaire included information such as the particular job that was important to the participant, the particular family member who was the most important to the participant, and what specific activities/hobbies the participant enjoyed, etc. An example of a personalized stimuli based on the family/social role is when participants listened to audiotapes prepared by the participant's family or made a family tree for the grandchildren An example of a personalized stimulus based on the participants professional role is when a former air force engineer was asked to construct a model plane (33). All personalized stimuli were designed so that:

○ It was directly related to the detailed content and/or context of the role identity

○ It was appropriate for the cognitive, physical and sensory abilities of the participant

○ It considered the demographics of the participant (e.g. gender, educational level, primary language)

Assessment of engagement

Observational Measurement of Engagement (OME)

The dimensions of engagement are measured in the following manner:

Engagement outcome measures

Rate of refusal whether or not the participant refused the stimulus.

Duration refers to the amount of time that the participant was occupied or involved with a stimulus, as observed by visually focusing on the stimulus, being physically occupied with the stimulus, turning body toward the stimulus or changing body position or handling of the stimulus. This measure starts after presentation of the engagement stimulus and ends at 15 minutes, or at the point when the participant stops being engaged with the stimulus. Duration is measured in seconds.

Attention to the stimulus occurs when the study participant is focused on the stimulus, i.e., eye tracking, visual scanning, facial, motoric or verbal feedback, or eye contact. Attention is measured on a 4-point scale: not attentive, somewhat attentive, attentive, and very attentive. Level of attention observed during most of the trial and the highest attention level during the trial are recorded.

Attitude toward the stimulus may be observed by positive or negative facial expression, verbal content or physical movement toward the stimulus. Positive attitude includes, when the study participant smiles, laughs, or shows other outward manifestation of happiness. Negative attitude includes participant aggressively pushes stimulus away (ex: starts to use toy blocks and then pushes them away angrily), throwing the stimulus, cursing, manifesting frustration at the stimulus (ex: watching a respite video and becoming angry at the video because they don't like to sing) and other outward manifestations of negativity. Attitude during an engagement trial is measured on a 7–point scale: very negative, negative, somewhat negative, neutral, somewhat positive, positive, and very positive. Attitude to the stimulus seen during most of the trial is recorded, as well as the highest rating of attitude observed during the trial.

Activity For this variable, we observed the participant's actions toward the stimulus during an engagement trial. Using a 4-point scale – none of the time, a little of the time (less than 16 seconds), some of the time, and most or all of the time – we recorded the amount of time that each of the following was observed during an engagement trial:

○ the participant held the stimulus

○ the participant manipulated the stimulus

○ the participant talked to the stimulus

○ the participant talked about the stimulus

○ the participant was disruptive

○ the participant inappropriately manipulated the engagement stimulus (e.g., eating or biting blocks)

○ other

The target of the participant's remarks while engaged was also noted. We recorded all targets to whom the participant spoke while engaged, including the stimulus itself, the participant him/herself, a staff member(s), another resident(s), research personnel, and other. Finally, we noted the content of the study participant's remarks while engaged, recording when the subject of the resident's words was the stimulus itself, the participant him/herself, a staff member(s), another resident(s), research personnel, and/or other. Sometimes it was not possible to determine the target or the content, which was recorded on the OME.

Data for the OME were recorded through direct observations using specially designed software installed on a handheld computer, the Palm One Zire 31™.

Results

Psychometric qualities of the OME

For these variables -- talking to object, talking about object, disruptive, and inappropriate -- results showed that over 80% of the responses were “none of the time”. For the purpose of analysis, these variables were dichotomized into ‘no’ = 0 and ‘yes’ = 1.

Inter-rater reliability

Inter-rater reliability of the OME was assessed by having 6 dyads of research assistants record responses on the engagement measures during 48 engagement sessions with nursing home residents. The inter-rater agreement rate (for 1-point discrepancy) was 84% for the engagement outcome measures and 92% for the action variables. Intraclass correlation averaged 0.78 for the engagement outcome variables and 0.65 for the action variables.

Correlations across items and across dimensions

In order to understand the relationships between the measurements of engagement, we examined the correlations across the measures. We calculated correlations among the engagement measures for each of the 24 stimuli, and each of the correlations was transformed into a z score using r to z transformation. A mean of these z scores was computed, and then this mean was transformed back to a correlation coefficient. The results are presented in Table 1 and show that:

1) The two measures of attention are extremely highly correlated, as are the two measures of attitude.

2) The following variables are related to the construct of engagement: engagement time, attention, attitude, manipulating object, and holding object. The variables disruptive and inappropriate are not correlated with engagement.

3) Although talking to the object and talking about the object are positively correlated with the engagement variables, the correlations are much lower than the correlations among the indicators of engagement.

4) The correlation between holding and manipulating indicated that those are highly related, though not identical, variables.

Table 1.

Correlations between the measurements of engagement

| Engagement duration (seconds) |

Attention-most of the time |

Attention- highest rating observed |

Attitude- most of the time |

Attitude- highest rating observed |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement time in sec-zero when refused |

|||||

| Attention most | 0.583 (96%) | ||||

| Attention highest | 0.601 (96%) | 0.905 (100%) | |||

| Attitude most | 0.483 (96%) | 0.730 (100%) | 0.735 (100%) | ||

| Attitude highest | 0.512 (96%) | 0.718 (100%) | 0.761 (100%) | 0.856 (100%) | |

| Manipulating object | 0.469 (83%) | 0.676 (88%) | 0.704 (88%) | 0.572 (83%) | 0.570 (83%) |

| Talking to object | 0.202 (42%) | 0.194 (33%) | 0.219 (37%) | 0.181 (42%) | 0.243 (59%) |

| Talking about object | 0.249 (83%) | 0.321 (91%) | 0.357 (92%) | 0.258 (71%) | 0.330 (92%) |

| Disruptive | 0.018 (4%) | 0.028 (0%) | 0.054 (0%) | −0.026 (9%) | −0.044 (13%) |

| Distracted | 0.123 (26%) | 0.074 (0%) | 0.085 (8%) | 0.112 (17%) | 0.119 (12%) |

| Inappropriate | 0.067 (8%) | 0.077 (17%) | 0.074 (12%) | 0.077 (8%) | 0.065 (8%) |

| Holding Object | 0.459 (91%) | 0.626 (87%) | 0.657 (92%) | 0.576 (83%) | 0.569 (83%) |

Note: the numbers are means of correlations for each of the 24 stimuli. The numbers in parentheses are the proportion of the original correlations that were significant at the .01 level.

Validity

We correlated the average level of observed engagement of participants with the independent ratings of activity therapists employed at the nursing homes of the participants' level of involvement in activities. The activity therapists were asked to report on how often the resident had been involved in activities during the last 2 weeks, and the level of interest and activity the resident had shown with these activities. The activity therapists, like the research assistants, were completely unaware of the observational data. The results are shown in Table 2. Whereas there were significant correlations between all the measures of observed engagement and the reports of the activity therapists, the highest correlations were between engagement time and the therapist's assessment of the frequency of the resident's involvement in activities, and between observed attention and the therapist's assessment of the level of activity of the resident during activities.

Table 2.

Correlations of observed engagement with reports by activity therapists.

| Items Rated by Activity Therapist | Engagement Duration (seconds) |

Attention-most of the time |

Attention- highest rating observed |

Attitude-most of the time |

Attitude- highest rating observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often has the resident been involved in activities during the last 2 weeks?(N=156) |

0.438*** | 0.408*** | 0.423*** | 0.427*** | 0.388*** |

| When participating in an activity, how interested is the resident in the activity?(n=128) |

0.253** | 0.409*** | 0.408*** | 0.370*** | 0.348*** |

| When participating in an activity, how active is the resident in the activity?(n=134) |

0.380*** | 0.561*** | 0.562*** | 0.511*** | 0.508*** |

P≤ .01

P≤ .001

Discussion

This paper lays the foundation for a new theoretical framework concerning the mechanisms of interactions between persons with cognitive impairment and environmental stimuli, as well as what factors are associated with interest and negative and positive feelings in engagement. Our study found that the most important dimensions of engagement are: refusal, attention and attitude. Engagement time is a global measure as it combines refusal and attention and therefore reflects an important clinical dimension. Future research is needed to investigate and, hopefully, disprove the common assumption that inactivity in dementia is a fixed part of the disease and therefore not a target for interventions. Moreover, research on engagement will add to the current theory of apathy in dementia, by clarifying the extent to which apathy is amenable to influence from setting characteristics.

This paper presents an assessment of engagement of persons with dementia through direct observations. The measure includes the following dimensions of engagement: engagement time, attention, attitude, manipulating, and holding object. Inter-rater reliability has been documented, as well as construct validity through independent ratings of participants by activity therapists who were not involved with the observations.

In future papers, we intend to describe the relationships between engagement and specific environment attributes, stimulus attributes, person attributes, and stimulus-person interactions. This paper lays the groundwork for such investigations.

Our ongoing and future studies open a new field of applied systematic exploration of engagement of nursing home residents with dementia in appropriate activities. We believe that our framework provides an exciting prospect for improving quality of life in persons with dementia in that it involves a complex yet replicable manner for analyzing engagement, and thereby identifying straightforward plans for tailoring appropriate activities to individuals. Such an understanding provides the next step in the overall development and validation of nonpharmacological approaches that deal with appropriate activities. It may also be useful for understanding other populations with cognitive disabilities.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AG R01 AG021497.

We thank the nursing home residents, their relatives, and the staff members and administration of the nursing homes for all of their help, without which this study would not have been possible

Footnotes

No Disclosures to Report

References

- 1.Leitner LM, Dunnett NGM, editors. Critical issues in personal construct psychotherapy. Krieger; Malabar, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conti R, Amabile TM, Pollak S. The positive impact of creative activity: Effects of creative task engagement and motivational focus on college students' learning. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21(10):1107–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Werner P. Observational data on time use and behavior problems in the nursing home. J Appl Gerontol. 1992;11(1):111–121. doi: 10.1177/073346489201100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgio LD, Scilley K, Hardin JM, et al. Studying disruptive vocalization and contextual factors in the nursing home using computer-assisted real-time observation. Psychol Sci. 1994;49(5):230–239. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.p230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper-Ice G. Daily life in a nursing home: Has it changed in 25 years? J Aging Stud. 2002;16(4):345–359. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, et al. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(1):140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buettner L, Lundegren H, Lago D, et al. Therapeutic recreation as an intervention for persons with dementia and agitation: An efficacy study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1996;11(5):4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelman K, Altus DE, Mathews RM. Increasing engagement in daily activities by older adults with dementia. J Appl Behav Anal. 1999;32(1):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orsulic-Jeras S, Judge KS, Camp CJ. Montessori-based activities for long-term care residents with advanced dementia: effects on engagement and affect. Gerontologist. 2000;40(1):107–111. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowlby-Sifton C. Making dollars and sense: The cost-effectiveness of psychosocial therapeutic treatment. Alzheimers Care Q. 2001;2(4):81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen-Mansfield J, Libin A, Marx MS. Nonpharmacological treatment of agitation: a controlled trial of systematic individualized intervention J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(8):908–16. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.8.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayers K, Griffin M. The play project: Use of stimulus objects with demented Patients. J Gerontol Nurs. 1990;16:32–37. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19900101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buettner L. Simple pleasures: A multilevel sensorimotor intervention for nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1999;14(1):41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farber JF, Schmitt FA, Logue PE. Predicting intellectual level from the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36(6):509–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark ME, Lipe AW, Bilbrey M. Use of music to decrease aggressive behaviors in people with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 1998;24(7):10–17. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19980701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas DW, Heitman RJ, Alexander T. The effects of music on bathing cooperation for residents with dementia. J Music Ther. 1997;34(4):246–259. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denney A. Quiet music: An intervention for mealtime agitation. J Gerontol Nurs. 1997;23(7):16–23. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19970701-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goddaer J, Abraham IL. Effects of relaxing music on agitation during meals among nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1994;8(3):150–158. doi: 10.1016/0883-9417(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ragneskog H, Brane G, Karlsson I, et al. Influence of dinner music on food intake and symptoms common in dementia. Scand J Caring Sci. 1996;10:11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1996.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. Management of verbally disruptive behaviors in nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52A(6):M369–M377. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.6.m369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerdner LA. Effects of individualized versus classical “relaxation” music on the frequency of agitation in elderly persons with Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(1):49–65. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerdner LA, Swanson EA. Effects of individualized music on confused and agitated elderly patients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1993;7(5):284–291. doi: 10.1016/0883-9417(93)90006-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabloski PA, McKinnon-Howe L, Remington R. Effects of calming music on the level of agitation in cognitively impaired nursing home residents Am J Alzheimers Care Relat Disord Res. 1995;10(1):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aronstein Z, Olsen R, Schulman E. The nursing assistants' use of recreational interventions for behavioral management of residents with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1996;11(3):26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sival RC, Vingerhoets RW, Haffmans PM, et al. Effect of a program of diverse activities on disturbed behavior in three severely demented patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(4):423–430. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Churchill M, Safaoui J, McCabe BW, et al. Using a therapy dog to alleviate the agitation and desocialization of people with Alzheimer's disease. Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1999;37(4):16–22. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19990401-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fritz C, Farver T, Kass P. Association with companion animals and the expression of noncognitive symptoms in Alzheimer's patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:459–463. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Fischer J. Characterization of family generated videotapes for the management of verbally disruptive behaviors. J Appl Gerontol. 2000;19(1):42–57. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woods P, Ashley J. Simulated presence therapy: using selected memories to manage problem behaviors in Alzheimer's disease patients. Geriatr Nurs. 1995;16(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4572(05)80072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacological interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: A review, summary, and critique American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen-Mansfield J, Golander H, Arnheim G. Self-identity in older persons suffering from dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(3):381–394. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen-Mansfield J, Parpura-Gill A, Golander H. Utilization of self-identity roles for designing interventions for persons with dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61B(4):202–212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]