Abstract

A 25-year-old woman was diagnosed to have tubercular meningitis (TBM) with a right parietal infarct. She responded well to four-drug anti-tubercular treatment (ATT), systemic steroids and pyridoxine. Steroids were tapered off in one and a half months; she was put on two-drug ATT after two months. Six months after initial diagnosis she presented with sudden, bilateral visual loss. Vision was 3/200 with afferent pupillary defect and un-recordable field in the right eye; vision was 20/60 in the left eye, pupillary reaction was sluggish and the field showed a temporal hemianopia. On reintroduction of systemic corticosteroids vision improved (20/120 in right eye and 20/30 in left eye) within three days; the field defects improved sequentially to a left homonymous hemianopia, then a left homonymous inferior quadrantonopia. A diagnosis of TBM, on treatment, with bilateral optic neuritis, and right optic radiation involvement was made. Since the patient had been off ethambutol for four months, the optic neuritis and optic radiation lesion were attributed to a paradoxical reaction to tubercular allergen, corroborated by prompt recovery in response to corticosteroids. This is the first report of optic radiation involvement in a paradoxical reaction in neuro-tuberculosis in a young adult.

Keywords: Anti-tubercular treatment, optic neuritis, optic radiation, paradoxical reaction, tubercular meningitis

Many of the symptoms, signs, and sequelae of tubercular meningitis (TBM) are the result of an immunologically directed inflammatory reaction to the infection.[1] Bacilli implanted to the meninges or brain parenchyma, result in the formation of small lesions (Rich foci). The location of the expanding Rich focus determines the type of involvement. Tubercles rupturing into the subarachnoid space cause meningitis. Those deeper in the brain parenchyma cause tuberculomas or abscesses. In addition, TBM may result in arachnoiditis and infarction.[2,3] While these lesions usually resolve following antitubercular therapy (ATT), clinical deterioration may occur in spite of recovery from meningitis. This worsening in neuro-tuberculosis has been attributed to a paradoxical response and may occur within days and even one year after starting chemotherapy despite regular, standard ATT.[4,5] This case is unusual in having an ophthalmic complication as part of a paradoxical reaction and presented to an ophthalmologist. Ophthalmologists must be aware of the occurrence of such reactions.

Case Report

A 25-year-old woman presented to the ophthalmology outpatient department with acute, marked loss of vision in both eyes over the last seven days. She had been well seven months earlier when she developed high-grade fever with chills and rigors associated with headache and vomiting. At that time she was seven months pregnant. She took treatment from a local practitioner without lasting relief. A month later she noticed reduced fetal movements for which she was brought to this hospital. Her blood pressure (BP) was 160/110 mm Hg and she had fetal distress for which emergency lower section caesarian section was done and a live neonate delivered.

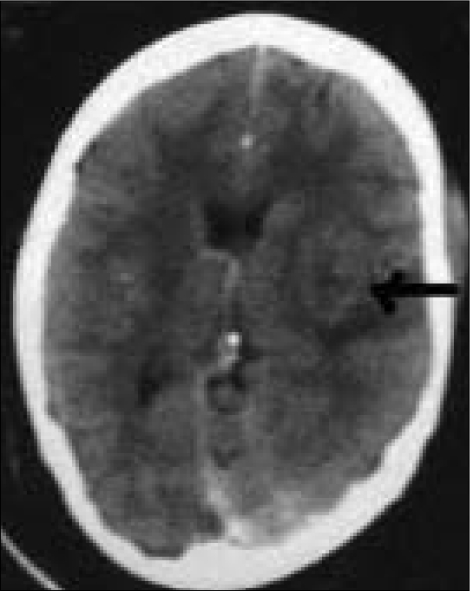

The patient developed altered sensorium the next day; BP was 160/108 mm Hg, pupils were recorded as being semi-dilated, reacting sluggishly. The right plantar reflex was extensor, left plantar was flexor and she had left lateral rectus palsy. No ophthalmologist examined her at that time, so the precise visual function is unknown. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology revealed a total leukocyte count of 35 cells/µL, 80% were lymphocytes; protein level was 11.1 mg/dL and glucose 34.2 mg/dL. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain showed an ill-defined hypodense lesion in the right parietal region suggestive of cortical infarct [Fig. 1]. CSF spaces, cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum and brainstem were normal. Chest radiogram was normal; she was HIV negative. Based on the history, clinical features, CSF and CT scan findings, a diagnosis of TBM with parietal infarction was made. She was started on standard four-drug ATT (tablets rifampicin 600 mg once daily, Isoniazid 450 mg once daily, pyrazinamide 1.5 g once daily and ethambutol 800 mg once daily), along with prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day, pyridoxine and antihypertensive drugs. During this period, apart from diplopia on left gaze, she had no visual symptoms and did not seek ophthalmic evaluation. Thus, the precise visual function at this time also is unknown. As response to treatment was satisfactory, corticosteroids were tapered off in one and a half months and she was put on two-drug ATT (tablets rifampicin 600 mg once daily and Isoniazid 450 mg once daily) after two months.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the brain in a patient with TBM. Image shows an ill-defined hypodense lesion in the right parietal region (arrow) suggestive of infarction

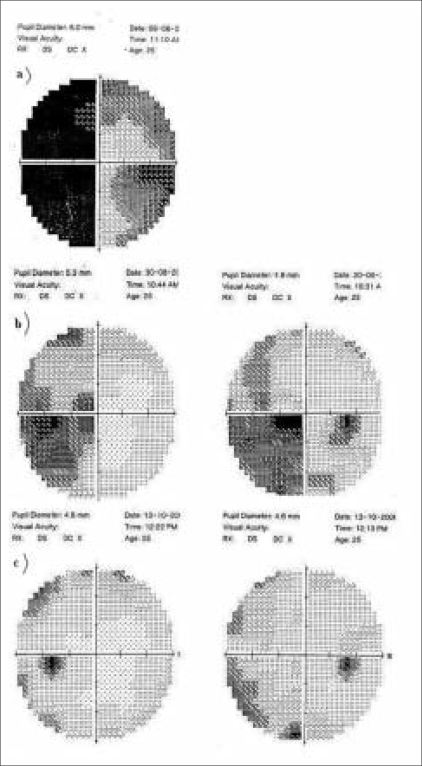

Four months after stopping corticosteroids she developed visual symptoms, for which she presented to us. At that time she had best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 3/200 in the right eye, with a marked relative afferent pupillary defect, mild temporal pallor of the optic disc with narrowed arteries, and un-recordable pattern reversal visually evoked potential (VEP) and visual field. BCVA was 20/60 in the left eye, with a mild afferent pupillary defect, and normal optic disc with narrowed arteries. VEP was subnormal (latency 96 ms, amplitude 0.977 µV of wave p100), and visual field revealed temporal hemianopia (Fig. 2a; measured using the Humphrey Field Analyzer and SITA program; Carl Zeiss Meditec; Carl Zeiss India Private Limited, Bangalore, India). Ocular movements were normal. A repeat CT scan of the brain was requested but was refused by the patient due to financial reasons. Blood pressure was normal. She was started on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day, to be tapered gradually, while two-drug ATT was continued.

Figure 2.

Successive Humphrey visual fields showing the resolving left homonymous field defect. The first field (a) was inadvertently measured using the SITA program; for uniformity, follow-up fields (b and c) were repeated using the same algorithm. The first field at a) was assessed prior to treatment of the paradoxical reaction; the fields at b) and c) were assessed at three weeks and two months after starting oral corticosteroid therapy

BCVA improved within three days to 20/120 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye; and within five days to 20/30 in both eyes. Visual fields improved to a left homonymous hemianopia. Three weeks after starting prednisolone, visual fields improved further leaving a residual left homonymous inferior quadrantanopia [Fig. 2b]. Repeat VEP, one month after starting prednisolone showed latency 116 ms and amplitude 2.03µV in the right eye; latency was 93.6 ms and amplitude 1.88 µV in the left eye. Pupillary reactions were normal, but the fundus picture was unchanged.

Two months after presentation vision was 20/20 in both eyes; visual fields showed only mild restriction in left halves [Fig. 2c]; VEP latency was 112 ms and amplitude 4.31µV in the right eye, and 98 ms and 7.5 µV in the left. Two months later oral corticosteroids and ATT were stopped. Her vision was maintained at 20/20 in both eyes eight months after first presenting to us.

Discussion

Expansion of a tuberculoma or development of multiple new brain lesions during treatment of TBM, though uncommon, has been reported in the literature and is called a paradoxical response.[6–9] It is possibly due to a Type IV hypersensitivity reaction developing within the initial lesion and resulting in cerebral vasculitis, infarction, and edema.[10] Clinicians may experience difficulty in differentiating a paradoxical reaction from a drug resistance or relapse of the disease. A combination of awareness of their occurrence, clinical judgment, and regular follow-up are essential for diagnosis.[5–9] There is also a need to report their occurrence so as to chronicle the entire spectrum.

The ATT regime prescribed for this patient had a lower dose of Ethambutol (800 mg versus 1200 mg) than that recommended by the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program.[11] Despite the lower dose she recovered well. Even when she developed ophthalmic signs after six months of ATT, there was no worsening of the systemic condition. Thus, she presented to an ophthalmologist rather than to a physician. She developed bilateral optic neuritis despite being off ethambutol, giving a clue to the immunological nature of the condition. The right parietal region had earlier revealed an infarction; presumably enhanced immunity caused an enlargement of the initial lesion resulting in involvement of the optic radiation. Resolution of the optic neuritis in response to corticosteroids unmasked the involvement of the optic radiation.

Ophthalmologists and physicians alike must recognize the occurrence of paradoxical reactions to avoid labeling the case as a new or resistant infection. The treatment of the primary disease should continue, corticosteroids being added or their dose enhanced. The rationale behind the use of adjuvant corticosteroids lies in reducing the harmful effects of inflammation as the antibiotics kill the organisms. The improvement seen with steroid therapy of paradoxical reaction in neuro-tuberculosis may be due to a reduction in cerebral edema and/or to a direct anti-inflammatory mechanism on the cerebral vasculature.[1,2]

This case is the first report of visual pathway involvement in a patient with a paradoxical reaction. It underscores the need for ophthalmologists to be aware of the occurrence of such reactions in neuro-tuberculosis; patients may present to them rather than to the treating physician.

References

- 1.Dastur DK, Manghani DK, Udani PM. Pathology and pathogenetic mechanisms in neurotuberculosis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1995;33:733–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalita J, Misra UK. Effect of methyl prednisolone on sensory motor functions in tuberculous meningitis. Neurol India. 2001;49:267–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta RK, Gupta S, Singh D, Sharma B, Kohli A, Gujral RB. MR imaging and angiography in tuberculous meningitis. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:87–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00588066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lees AJ, McLeod AF, Marshall J. Cerebral tuberculoma developing during treatment of tuberculous meningitis. Lancet. 1980;1:1208–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar R, Prakash M, Jha S. Paradoxical response to chemotherapy in neurotuberculosis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2006;42:214–22. doi: 10.1159/000092357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safdar A, Brown AE, Kraus DH, Malkin M. Paradoxical reaction syndrome complicating aural infection due to mycobacterium tuberculosis during therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:625–7. doi: 10.1086/313731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiser M, Fatkenheuer G, Diehl V. Paradoxical expansion of intracranial tuberculomas during chemotherapy. J Infect. 1997;35:88–90. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)91241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta M, Bajaj BK, Khwaja G. Paradoxical response in patients with CNS tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalkan A, Serhatlioglu S, Ozden M, Denk A, Demirdag K, Yilmaz T, et al. Paradoxically developed optochiasmatic tuberculoma and tuberculous lymphadenitis: A case report with 18-month follow up by MRI. South Med J. 2006;99:388–92. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000209091.57281.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hejazi N, Hassler W. Multiple intracranial tuberculomas with atypical response to tuberculostatic chemotherapy: Literature review and a case report. Infection. 1997;25:233–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01713151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New Delhi: Central TB Division, DGHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman Bhavan; 2005. Managing the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme in your area. Modules 1-4; pp. 82–107. [Google Scholar]