Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages are antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that are important in innate immune defense as well as in the generation and regulation of adaptive immunity against a wide array of pathogens. The genitourinary (GU) tract, which serves an important reproductive function, is constantly exposed to numerous agents of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). To combat these STIs, several subsets of DCs and macrophages are strategically localized within the GU tract. In the female genital mucosa, recruitment and function of these APCs are uniquely governed by sex hormones. This review summarizes the latest advances in our understanding of DCs and macrophages in the GU tract with respect to their subsets, lineage, and function. In addition, we discuss the divergent roles of these cells in immune defense against STIs as well as in maternal tolerance to the fetus.

INTRODUCTION

The genitourinary (GU) tract performs the vital functions of reproduction and urine elimination. As a consequence, the GU tract is constantly exposed to a wide array of pathogens, many of which are sexually transmitted. The estimated total number of people living in the United States with viral sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is over 65 million.1 Every year, there are at least 19 million new cases of STIs. In addition to causing suffering, pain, and grief, the direct medical costs of STI treatment for all estimated cases in the United States per year is at least $8.4 billion.1 Although bacterial STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis are treatable with antibiotics, viral STIs caused by human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2), human papillomavirus (HPV), and hepatitis B are incurable leading to life-long infection with severe morbidity and in some cases mortality. To allow optimal functions of the GU tract while protecting the host from harmful pathogens, the immune system of the GU tract must be tightly regulated. In particular, the female reproductive tract is equipped with several different immune compartments that are under the regulation of sex hormones. Such hormone-dependent regulation presumably reflects optimization of immunity that is compatible with fertilization and fetal development. Despite the dire effects of STIs on world populations, surprisingly little is known about the mechanism of immune protection in the GU tract. Here we review our current understanding of the individual cell types present within the GU tract and their roles in mucosal defense.

EPITHELIAL LINING OF THE GU TRACT

The female genital tract is comprised of the upper reproductive tract (oviducts, ovaries, uterus, and endocervix) and the lower reproductive tract (ectocervix and vagina). These tissues are classified as two distinct types of mucosae (types I and II) according to the epithelia that cover the mucosal surface.2 The upper reproductive tract is covered by simple columnar epithelium that is hormonally regulated to allow for fertilization and fetal development (type I), whereas the lower reproductive tract is lined with protective multilayered stratified squamous epithelial cells (type II). In contrast to the type II mucosa, the type I mucosal epithelium expresses polymeric Ig receptor, capable of allowing dimeric IgA to access the lumen. The male GU tract consists of testes, efferent ducts, epididymis, ejaculatory ducts, ductus deferens, urethra, and penis. The posterior urethra is lined by a transitional epithelium, and the anterior urethra by a distinct epithelium composed of a single layer of columnar cells at the surface and a stratified or pseudos-tratified epithelium of small cells with round nuclei at the base. STI agents gain access through the urethral opening of the penis, as well as through the inner surface of the foreskin. Although epithelial cell structures that line the reproductive tract clearly have a critical function in immune defense at this important mucosal surface, other cell types, including DCs and macrophages, likewise are required for protection in the GU mucosa.

DENDRITIC CELLS IN THE GU TRACT

The female genital tract is immunologically unique in its requirement for tolerance to the allogeneic sperm and, in the upper tract, to the conceptus. DCs and macrophages are the major antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in mucosal organs including the GU tract. At steady state, the main DC populations in the genital mucosa consist of those that reside within the epithelium (Langerhans cells) and those that reside beneath the epithelium in the submucosa (submucosal DCs).3 However, during infection or inflammation, both monocyte-derived DCs4 and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs)5 are recruited from peripheral blood to the vaginal mucosa. The cell-surface markers (described below) help to identify these DC subsets within various compartments of the genital tract.

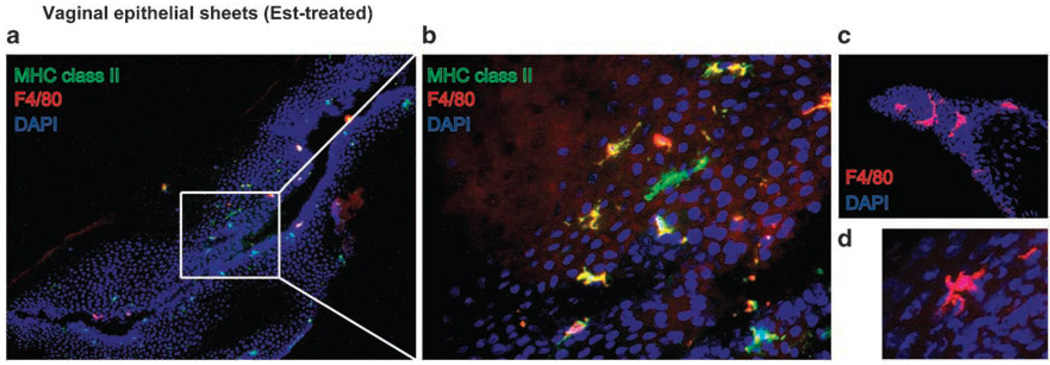

Within the stratified squamous epithelial layer of the type II mucosa, Langerhans cells (Langerin+ major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II+ DCs) are the predominant APCs.2,6 In human genital tract, a large number of Langerin+ HLA-DR/DP/DQ+ Langerhans cells reside in the epithelia of the vagina and ectocervix.7–9 As a typical feature of Langerhans cells, these cells contain racquet-shaped vesicles known as Birbeck granules. Langerin, a C-type lectin responsible for the formation of Birbeck granules, is expressed by Langerhans cells within various mucosal epithelia.10,11 Further, a CD1a+ population of DCs, another cell-surface marker of Langerhans cells, has been found in lower frequencies in the cervico-vaginal epithelium8,12,13 and the oviduct epithelium.14 These cells express a chemokine receptor, CCR5, which is the coreceptor for R5-tropic HIV-1.7,15 In addition, DCs in the female genital tract are found to express Fc receptors for IgG, FcγRII, and FcγRIII, in most vaginal, ectocervical, and transformation zone epithelia.16 Thus, these DCs may be capable of uptake of immune complexes through these FcR for presentation to T cells upon migration into the local lymph nodes (LNs). CD1a+ Langerhans cells were also detected in the oviduct epithelium.14 These cells extend cell processes along the base of the epithelium and are ultrastructurally characterized by rod-shaped Birbeck granules and a well-developed Golgi apparatus.14 In rhesus macaques, CD1a+ cells are also present in the stratified squamous epithelium of the vagina and ectocervix.17 Distinct from human tissues, these CD1a+ cells are also found within the columnar epithelium of the endocervix.17 However, Langerin expression or the presence of the Birbeck granules in these cells remains unknown. In the murine vaginal epithelium, MHC class II+ DCs (vaginal epithelial DCs; VEDCs) reside in the vaginal and cervical epithelium,4,18 and these cells have unique features compared with the skin Langerhans cells. We prefer to use the term “VEDCs” to describe mouse vaginal Langerhans cells because they express very little Langerin, and are sufficiently different from conventional Langerhans cells in lineage, turnover and phenotype.4 One is that these VEDCs express Langerin at a low level4 and contain cup-shaped granules but not racquet-shaped granules in the cytoplasm.18 Another is that VEDCs are heterogeneous compared with skin Langerhans cells. At least four populations of the VEDCs have been identified consisting of I-A+/F4/80+, I-A+/F4/80−,I-A−/CD205+, and I-A+/CD205− populations by immunohistochemistry18 and CD11b+F4/80hi, CD11b+F4/80int, and CD11b−F4/80− populations by flow cytometry.4 A typical distribution pattern of VEDCs in the epithelia of mouse treated with estradiol is depicted (Figure 1). It is unknown whether these distinct populations are endowed with specific functions in immune responses in the vaginal mucosa. Future studies must examine whether human vagina contains similar counterparts and also determine the relevance of these populations in innate defense and antigen presentation upon infection with sexually transmitted pathogens.

Figure 1.

Heterogeneous populations of vaginal epithelial dendritic cells (DCs). The epithelium of the vagina from 17β-estradiol-treated mice was separated from the lamina propria. Frozen sections of the epithelium were stained with Abs against major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (green) and F4/80 (red). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Images were captured using an original magnification ×10 (a) or ×40 objective lens (b–d). DAPI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

In the lamina propria of the female genital tract, there is a network of MHC class II+ DCs. Such lamina propria DCs have been shown to consist of several subsets; DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN)+ (human and macaques),9,19 CD123+ DC (macaques),20 and CD11b+ DCs (murine).3 The function of the submucosal DCs in immunity against STIs will be discussed below.21 In the murine uterus, heterogeneous populations of MHC class II+ F4/80+ cells containing CD11c+, 33D1+, and CD1+ cells are also observed by flow cytometric analysis.22 The functions of these and other DC subsets in immune tolerance to fetus will be discussed below.

MONOCYTES AND MACROPHAGES IN THE GU TRACT

In contrast to DCs that express constitutively high levels of MHC II, monocytes and macrophages generally express very low levels of MHC II at steady state. Under inflammatory conditions, monocytes can differentiate into monocyte-derived DCs capable of presenting antigens on MHC II. In addition, macrophages can become activated to upregulate the level of MHC II. This allows macrophages to sense interferon (IFN)-γ from Th1 effector cells in the tissue, resulting in enhanced degradative capacities and elimination of pathogens within the phagolysosomes. Distinct subsets of macrophages have been found in the GU tract. CD14+ CD68+ macrophage populations have been identified in human vaginal and cervical tissues.12,23,24 Although the gut and lung show a preponderance of suppressive macrophages (D1+ D7+), the vast majority of stromal macrophages in the human cervical tissues are D7+ effector cells, with only small populations of D1+ inductive cells and D1+ D7+ suppressor cells.25 Further, CCR5-expressing CD68+ macrophages were abundantly present in the vaginal lamina propria.20 Although F4/80 and CD11b have been used as markers of macrophages in mice, these molecules are also expressed by DCs and Langerhans cells, making it difficult to clearly delineate macrophages from DCs. Definitive markers that can distinguish DCs, monocytes, and macrophages are needed to study the role of these important leukocytes in immunity in the GU tract.

ORIGIN OF DCS AND MACROPHAGES IN THE GENITAL TRACT

In the intestine and lung, monocytes are a direct precursor of the lamina propria DCs.26 Although VEDC populations are located in the stratified squamous epithelium of the vagina,18 these DCs, unlike the skin Langerhans cells,27 are rapidly repopulated by a bone marrow-derived precursor at steady state.4 Several groups have characterized at least two types of DC precursors—(1) nonmonocyte CD11c+ MHC class II− precursors, which are found in the bone marrow and secondary lymphoid organs,28 and (2) a common DC precursor (Lin− CSF1R+ c-kitint Flt3+) that develops into cDC and pDC in the bone marrow.29,30 It is unknown whether DCs and macrophages in the genital tract are derived from such precursors. In contrast, under inflammatory conditions caused by HSV-2 infection, VEDCs differentiate from a Gr-1hi monocyte population,4 much like the case of monocytes giving rise to skin Langerhans cells under inflammatory conditions.31 It remains unclear what the relative contributions of these monocyte-differentiated DCs and the tissue-resident DCs are in defense against pathogen invasion.

SEX HORMONE REGULATION OF DCS AND MACROPHAGES IN THE FEMALE GENITAL TRACT

Mucosal immunity in the female genital tract is under the regulation of sex hormones.32 Although the effect of male sex hormones on DCs and macrophages in the male GU tract is unknown, much is understood regarding sex hormone regulation of the immunological environment of the female genital mucosa.

The ovarian cycle begins by the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone by the anterior pituitary gland, which stimulates the follicle to develop. As the follicle matures, the outer cells begin to secrete estrogen. Ovulation is initiated by a surge of another hormone from the anterior pituitary, luteinizing hormone. This hormone also influences the development of the corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. In rodents, the estrous cycle is comprised of four distinct phases: proestrus, estrus, metestrus, and diestrus. During metestrus–diestrus, but not proestrus, numerous mucin-secreting cells are observed in the vaginal epithelium. In parallel, VEDCs in the epithelium are most numerous at this phase.3,18 In addition, on the basis of ultrastructural morphology, three distinct types of VEDCs are detected in the epithelium during the estrous cycle,33 suggesting that sex hormones may control their phenotype and function. In mice, the uterus at estrus contains F4/80− MHC class II+ CD11c+ DCs and F4/80+ CD11b+ monocytes and macrophages. The presence of the monocytes, but not DCs, was dependent on the ovarian steroid hormones, as determined in ovariectomized mice.22 In humans, the menstrual cycle is comprised of three main phases; follicular/proliferative phase consisting of menstrual (days 1–5) and preovulatory (days 7–12) stages and luteal/secretory phase, which is postovulatory (days 19–24). The number of VEDCs and macrophages during the menstrual phase was reported to be slightly higher compared with other phases.34 Similarly, the frequencies of immature DCs in human cervical mucosa were also reported to be higher during the menstrual phase.35 Whether these changes in the DCs and macrophages have a functional significance in innate and adaptive immune responses in the genital mucosa is unknown.

In addition to the changes in macrophage and DC recruitment to the genital tract, the ovarian cycle also influences the thickness and permeability of the epithelia lining the tissue. In mice, this results in dramatic changes in the thickness of the vaginal epithelia: 2–3 cell layer thick at diestrus compared with > 12 cell layer thick during estrus.3 The use of hormone-based contraceptives including oral contraceptive pills and depo-medroxy-progesteron acetate (Depo-Provera) is known to influence the frequencies of immunocompetent cells and epithelial thickness in the genital mucosa. Although the precise mechanism by which hormone contraceptives modulate genital mucosal immunity is unclear, in rhesus macaques, progesterone was shown to significantly reduce the thickness of the vaginal epithelium and increase SIV susceptibility.36 In addition, progesterone implantation is reported to increase the number of Langerhans cells in human vaginal epithelium,37 whereas no differences in the number of CD1a+ Langerhans cells and CD68+ macrophages were detected.23 Moreover, in vitro treatment with progesterone was shown to decrease virus-induced IFN-α production by human and mouse pDCs.38 These findings suggest that the modulation of DC subsets and macrophages by endogenous or exogenous sex hormones might affect susceptibility to sexually transmitted viruses in the female genital tract. Despite these changes detected in the genital mucosa, epidemiological studies examining a correlation between hormonal contraception and risk of sexually transmitted pathogen acquisition have reported mixed results. A comprehensive review39 of 83 studies published between January 1966 and February 2005 for evidence relevant to all hormonal contraceptives and STIs found that, although studies of combined oral contraceptive and depot medroxy-progesterone use generally reported positive associations with cervical chlamydial infection, not all associations were statistically significant. For other STIs, the findings suggested no association between hormonal contraceptive use and STI acquisition, or the results were too limited to draw any conclusions. On the basis of these results, according to the WHO Expert Working Group, hormonal contraceptive use is not associated with any increase in the risk of acquisition or transmission of STIs.40

MUCOSAL MICROENVIRONMENT REGULATES THE FUNCTION OF DCS AND MACROPHAGES IN THE GU TRACT

On the basis of microflora, the female genital tract can be divided into two compartments: (1) the lower reproductive tract including vagina and ectocervix, with abundant commensal flora, and (2) the upper reproductive tract including uterus and fallopian tubes, which are sterile.41 In the lower tract, the stratified squamous epithelium of the vagina and ectocervix offers a physical barrier capable of withstanding coitus and defending against sexually associated pathogens, whereas the monolayered columnar epithelium of the endocervix and uterus provides an immune-privileged site suitable for fertilization and fetus development. In addition, both types of epithelia contain mucus-secreting cells to prevent entry of harmful bacteria while allowing sperm to ascend to the uterus. Throughout the genital tract, the epithelium secretes various antimicrobial peptides/proteins including secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor, human β-defensin-2 (hBD-2), and surfactant protein A (SP-A) as well as constitutive secretion of interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-6, and transforming growth factor-β.42–44 Here we describe the evidence suggesting that these proteins not only kill invading pathogens but also serve to condition local APCs.

Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor has been shown to inhibit HIV and HSV infection in vitro and may be important in innate mucosal defense against STIs by restricting infection and/or tropism in the local mucosal tissue.45,46 Likewise, defensins, which are secreted by cervical epithelium, also inhibit HIV-1 and HSV infections,40,47 revealing the potential importance of such innate defense mechanisms. It is reported that hBD-1–3 are mainly expressed in epithelial tissues of various organs, such as skin, respiratory, and the GU tract.44,48,49 Defensins have been demonstrated to exhibit biological activities beyond destruction of hazardous microbes.50 These contribute to the generation of adaptive immunity by exhibiting chemotactic activity on DCs through the chemokine receptor CCR6 (hBD-1, hBD-2, and hBD-3)51–53 and on monocytes and macrophages (hBD-3).54 Murine BD-2 has been shown to activate DCs through Toll-like receptor (TLR)4.55 Further, human defensins are known to activate macrophages through TLR1 and TLR2 (hBD-3) and block HPV infection (hα defensins) and HIV-1 replication in vitro (hBD-2 and hBD-3).56,57 These findings suggest that defensins, particularly hBD-2 that is constitutively expressed in the female genital tract, might promote differentiation and activation of DCs and macrophages in the GU tract44 and exemplify the dual role of innate defense mechanisms in direct inhibition of pathogen replication and activation of immune cells in the local mucosal tissues.

SP-A, originally characterized as a component of the lung surfactant system, is now recognized to be an important contributor to mucosal immune defense by stimulating macrophage chemotaxis and enhancing the binding and killing of bacteria and viruses.58 SP-A is known to regulate TLR expression on human alveolar macrophages59 and facilitate phagocytosis of microorganisms by opsonization of bacteria, fungi, and viruses.58,60 In addition, SP-A downregulates oxidant production by decreasing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity in human monocyte-derived macrophages.61 Moreover, SP-A has been shown to modulate the differentiation and chemotaxis of monocyte-derived DCs.62 In the human female genital tract, SP-A is produced by a specific vaginal epithelial cell population in the intermediate layer and also found in vaginal lavage fluid.43 These findings suggest that differentiation and function of DC and macrophages is influenced by SP-A in the female genital tract.

The epithelial control of DC function goes beyond regulation mediated by antimicrobial peptides. Our earlier study demonstrated a function for epithelial innate recognition of HSV-2 infection in the generation of adaptive immunity.63 As a first line of innate immune protection against STI, the recognition of invading pathogens is accomplished by specific pattern recognition receptors including the TLRs. Following genital HSV-2 infection, mice deficient in MyD88, an obligatory adaptor of TLRs, are incapable of generating Th1 responses.63 As expected, MyD88 expression in the hematopoietic compartment, which includes DCs, was required to generate Th1 responses following HSV-2 infection. Interestingly, when mice deficient in MyD88 in the nonhematopoietic compartment were infected with HSV-2, these mice also failed to induce Th1 immunity.63 DCs isolated from the draining LN of such mice had reduced capacity to stimulate Th1 cells ex vivo, indicating the requirement for TLR-mediated stromal signals for full activation of DCs in vivo.63 A similar finding was reported for oral infection with Toxoplasma gondii. In this study,64 a reduced frequency of IFN-γ-secreting cells was found in response to T. gondii infection in TLR9-deficient mice. By examining the requirement for TLR9-mediated recognition of the parasite by hematopoietic vs. nonhematopoietic cells in bone marrow chimeric mice, Th1 response was found to be reduced in mice that lack TLR9 in either compartment. This resulted in the amelioration of Th1-mediated ileitis in these mice.64 Collectively, these studies demonstrated the importance of stromal TLR-mediated recognition of pathogens in the generation of adaptive Th1 immunity.

ROLE OF GU DCS AND MACROPHAGES IN IMMUNE DEFENSE AGAINST STIS

Dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages are capable of mediating innate defense against a variety of pathogens. Various TLRs have been reported to be expressed on DCs and macrophages,65 as well as on nonhematopoietic cells such as the vaginal epithelial cells in the female reproductive tract.66 TLR1, −2, −3, −5, and −6 were reported to be expressed on the epithelia of different regions of female reproductive tract. TLR4 is expressed in the endocervix, endometrium, and uterine tubes but not in the vagina and ectocervix.67 At the functional level, bone marrow chimeric mice lacking TLR9 in the stromal compartment were impaired in CpG-mediated innate protection against HSV-2 infection, indicating that stromal cell populations in the vagina express functional TLR9 under this condition.68 Among genital APC populations, one of the DC subsets was found to express TLR9,69 and DCs in human deciduae have been found to be TLR2 negative.70 In addition to the TLRs, DCs, and macrophages, as well as the epithelia and other stromal cells in the GU tract express pattern recognition receptors including NOD-like receptors and RIG-like receptors, which are critical in mediating antimicrobial and antiviral defense.71,72 However, the precise function of these pattern recognition receptors on innate and adaptive immunity in the GU tract is unknown.

Dendritic cells are considered to be the most potent APCs capable of activating naive and memory T cells.73,74 In contrast, macrophages are known to specialize in the phagocytic elimination of invading pathogens although these populations also have antigen-presenting capacity.75 An important feature that distinguishes these populations is their capacity to migrate to the draining LNs. Upon uptake of antigens and recognition of pathogens, peripheral DCs, but not macrophages, migrate to the draining LNs to prime naive T and B cells. In the mouse model of genital herpes infection, vaginal CD11b+ submucosal DCs, but not Langerhans cells, have been shown to migrate to the genital draining LNs and initiate HSV-specific Th1 cell differentiation.3 Interestingly, although the Th1-inducing capacity depends on MyD88 expression by DCs, maturation and migratory capacity of these cells is independent of MyD88 signaling.63

Within the stratified squamous epithelial layer of the vaginal and ectocervical mucosa, the Langerhans cells represent the primary APCs. Both Langerhans and submucosal DCs have been shown to have a function in HIV-1 transmission and defense.6 The Langerhans cells were one of the first cell types to be identified to mediate transmission of HIV-1.9 Elegant ex vivo models of HIV-1 infection demonstrated that CD1a+ Langerhans cells and CD4+ T cells in the vaginal epithelium primarily endocytose HIV-1 virus.13 On the other hand, numerous F4/80+ CD11b+ MHC class II+ DCs are also detected within the foreskin epithelium of the male urogenital tract.76 Recently, DCs in the human foreskin were demonstrated to confer protection against HIV-1 transmission through Langerin-mediated degradation of the virus.77 In addition, in vitro generated Langerhans cells have a cytotoxic activity against cervical epithelial cells expressing HPV16 E6 and E7.78 As HPV infection is known to decrease the frequency of the Langerhans cells in the human cervical epithelium,8 this may represent a dire situation in which the cancer could grow uninhibited by the ablation of Langerhans cells. Together, these observations suggest that Langerhans cells provide critical antiviral defense functions and suggest that treatments to augment such activities may prove to be useful therapeutic targets.

In addition to the Langerhans cells, the submucosal DCs of the GU tract express DC-SIGN (CD209), which is a C-type lectin with capability of binding to a variety of pathogens including HIV-1.79 Instead of being degraded in the lysosome, HIV-1 has usurped the function of DC-SIGN to hide in nondegra-dative multivesicular bodies upon endocytosis through DC-SIGN. DC-SIGN-bound HIV-1 virions can then be released to the infectious synapse and facilitate trans-infection of CD4T cells.80 DC-SIGN+ DCs were found to reside in the lamina propria of human cervical and vaginal epithelium, rectal mucosa, and male foreskin.9,81,82 Subsequent studies have revealed the involvement of other C-type lectins that facilitate binding and enhancing infection of T cells by DCs in the genital tract.21 In addition, Syndecans expressed on monocyte-derived DCs and macrophages have also been shown to bind to HIV and promote viral transmission to CD4+ T cells.83,84 Although the overall number of CD68+ cells detected in HIV+ patients was comparable to that in low-risk patients, the proportion of D1+ D7+ cells were significantly decreased.25 In fact, a higher proportion of CD68+ HLA-DR+-activated macrophages in the epithelium was observed in HIV+ subjects.85 Macrophages as well as Langerhans cells and CD4+ T cells are known to be susceptible to R5-tropic HIV-1.86,87 CD14+ macrophages isolated from vaginal organ culture express both CCR5 and CXCR4, suggesting that they may also be susceptible to X4-tropic HIV-1.15 In rhesus macaques, a significant number of CD68+ macrophages were also found in the submucosa of the vagina, ectocervix, and endocervix.

A large number of leukocytes, including DCs and macrophages, are known to be recruited to the site of inflammation and infection in peripheral tissues.88 Following intravaginal HSV-2 infection, pDCs are recruited to the vaginal tissue and produce large amounts of IFN-α.5 pDCs recognize HSV-2 through the TLR9 to provide the first line of immune defense. Furthermore, this subset is required for CpG oligodeoxynucleotide-mediated protection against lethal intravaginal HSV-2 challenge.68 In this model, at the very early stage of CpG treatment (12 h), CD11c− F4/80+ MHC class II− macrophages were shown to be recruited into the vaginal tissues.89 In addition, CD11b+ DCs are also known to accumulate at the site of CpG treatment as well as chlamydial and HSV-2 infection.3,90 At a later stage of the immune response, once the antigen-specific T cells are generated, a large number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are recruited to the vaginal tissue (~ 4–7 days postinfection).91,92 These findings suggest that viral inflammatory signals catalyze a selective recruitment of immune cells to the local mucosal tissue through the vascular endothelium via the production of specific chemokines and adhesion molecules to coordinate the access to various leukocyte populations that are needed to most efficiently recognize and clear infection.

Recruitment of the relevant cell types into the genital mucosa can be usurped by other viruses for replication. HSV-2 infection is associated with an increased population of CD11c+ CD1a+ DC-SIGN+ DC and CCR5+ CD4+ T cells in the human cervical tissues.69 Unfortunately, HSV-2 infection results in the accumulation and activation of the HIV-1 target cell population, suggesting a potential negative impact of HSV-2 infection on HIV transmission.93 In fact, epidemiological studies demonstrated that HSV-2 infection represents a high-risk factor for HIV-1 transmission.93 In addition, significant depletion of DC-SIGN+ and TLR9+ DCs in the genital tract of HSV-2- and HIV-coinfected patients was observed.69 Further, HSV-2 shedding was shown to increase in the genital tissues of HIV-1-infected patients, suggesting that DC-SIGN+ and TLR9+ DCs potentially control HSV-2 reactivation in the genital mucosa. These observations collectively demonstrate the complexities associated with simultaneous mucosal infections and the potential for one mucosal infection to negatively affect the outcome of infection during a subsequent infection.

Genital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis represents one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases. C. trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacteria that establishes infection in the GU tract. The major clinical manifestations of genital chlamydial infection in women include mucopurulent cervicitis, endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Previous studies demonstrated that DCs pulsed ex vivo with heat-killed Chlamydia elementary bodies activate Th1 cells, and such vaccination confers protection against murine model of Chlamydia infection.94 A subsequent report demonstrated that DCs pre-treated with live, but not ultraviolet-treated, C. muridarum become mature and effectively promote Chlamydia-specific Th1 responses.95 In addition, peritoneal macrophages secrete significant amounts of IFN-β and IP-10 following in vitro C. trachomatis infection.96 However, it remains unclear which type of DCs migrate into draining LNs to initiate Th1 cell differentiation and the possible protection mechanism mediated by resident macrophages at the site of Chlamydia infection in the GU tract. Future studies will be required to identify both the resident and recruited APC populations in the local mucosal tissue following infection with this important mucosal pathogen, and which of these cells mediates protective immunity.

ROLE OF DCS AND MACROPHAGES IN MATERNAL IMMUNE TOLERANCE TO FETUS

During pregnancy, precise regulation of innate and adaptive immunity at the maternal–fetal interface is required to maintain the survival of the semiallogeneic embryo. At the same time, effective immunity must be maintained at the mucosal border to protect both mother and fetus from harmful pathogens. Maternal DCs are distributed throughout the decidualized endometrium during all stages of pregnancy. Decidual DCs are identified as two distinct populations: CD11c+ MHC class IIhi CD11b+ CD14− Lin− and CD11c+ MHC class IIint CD11b+ CD14− Lin− DCs. These subsets are negative for CD1a, a marker of Langerhans cells, and CD123, a marker of human pDCs. A C-type lectin, DEC-205, but not DC-SIGN, is expressed in the decidual DCs.70 Costimulatory molecules and DC activation markers, CD40 and CD83, on these DCs were detected at low levels. On the other hand, other groups identified CD83+ CD45+ HLA-DR+ CD14− CD206+ mature-type DCs in the human deciduae.97–99 As CD83+ DCs were shown to stimulate the proliferation of allogeneic T cells in vitro,97 it is conceivable that CD83+ DCs exert immunostimulatory function in the deciduae. In addition, CD83+ DCs derived from human peripheral blood have been known to augment the cytolytic capacity of CD56+ natural killer (NK) cells.100 In human deciduae, the most abundant lymphocyte subset is the uterine-specific NK cells.101 Thus, this DC subset could have a function in regulating NK cell activity to coordinate the immunity against harmful pathogens whereas others might be involved in maintaining the capacity to support pregnancy. Conversely, the same cells may exert differential tolerant vs. immune induction signals as a result of local conditioning. In addition, trophoblast cells express HLA-G, which protects them from lysis by NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Further studies will be required to fully elucidate these important immunoregulatory mechanisms operative during pregnancy.

The composition of the DC subsets changes during the different stages of pregnancy. In the first trimester of pregnancy, BDCA-1 (CD1c)+ (myeloid DC type 1, MDC1), BDCA-2 (CD303)+ CD123+ (pDC), and BDCA-3 (CD141)+ (MDC2) DC subsets were identified in the deciduae.102 The proportion of BDCA-1+ DCs in deciduae was comparable to that in peripheral blood, although pDC frequency was much lower in the decidua compared with the peripheral blood. In contrast, the ratio of BDCA-3+ DCs in the deciduae is higher than that in the peripheral blood and the number of MDC2+ DCs continued to increase at 9 weeks postgestation.102 BDCA-1+ as well as BDCA-3+ DC subsets were found to express costimulatory molecules including CD80 and CD86 at low levels. In addition, these populations were found to express immunoglobulin-like transcript 3, an inhibitory receptor involved in immune tolerance.102 These findings suggest that the DC subsets in the deciduae represent immature and possibly tolerogenic DCs, and could be involved in the regulation of T-cell and NK cell-mediated immune responses against fetal allograft at the maternal–fetal interface.

CD14+ macrophages are also present in the deciduae.103 The CD14+ HLA-DR+ macrophages express CD86 at low levels.103 During gestation, the phagocytosis of the trophoblast cells is critical for the resolution of inflammation in the decidua. In terms of scavenger receptor-mediated phagocytosis, the macrophages are known to express the endocytic receptor CD206.99 CD206 can bind to and internalize glandular secretor phase mucin tumor-associated glycoprotein-72 (TAG-72).99 The binding of TAG-72 to CD206 on deciduae macrophages is further demonstrated to block endocytosis of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dextran in vitro.99 Therefore, as TAG-72 is expressed in the endometrium of the normal female reproductive tract at secretory phase but during the not proliferative phase,104,105 it implies that hormonally controlled TAG-72 expression might be involved in the regulation of phagocytosis of trophoblasts by macrophages.

It had been reported that CD14+ monocyte/macrophage derived from human decidua secrete IFN-γ, IL-4, and large amounts of IL-10 spontaneously in vitro.106 These macrophages are further demonstrated to have IL-10-mediated immunosuppressive function in pregnancy,107 which could contribute to the induction of tolerance against the developing fetus. Lamina propria macrophages in the small intestine are known to induce the differentiation of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells mediated by IL-10, retinoic acid, and transforming growth factor-β.108 It would be interesting to determine whether decidual macrophages are also capable of inducing regulatory T cells specific for the semiallogeneic fetus and support fetal development.

CONCLUSION

Despite being the primary site of entry for sexually transmitted pathogens, very little information is available concerning the DCs and macrophages in the GU tract. Future research will hopefully provide us with a deeper understanding of the immune mechanisms of DCs and macrophages in the GU tract. Such knowledge is critical in designing and developing effective vaccines against STIs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants from the NIH/NIAID (AI054359, AI 062428, and AI064705). JMT was supported in part by grant T32 AI07019 from the NIAID. AI holds an Investigators in Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Social Health Association . Sexually Transmitted Diseases in America: How Many Cases and at What Cost? Research Triangle Park, NC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki A. Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007;25:381–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao X, et al. Vaginal submucosal dendritic cells, but not Langerhans cells, induce protective Th1 responses to herpes simplex virus-2. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:153–162. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iijima N, Linehan MM, Saeland S, Iwasaki A. Vaginal epithelial dendritic cells renew from bone marrow precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19061–19066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707179104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund JM, Linehan MM, Iijima N, Iwasaki A. Cutting edge: plasmacytoid dendritic cells provide innate immune protection against mucosal viral infection in situ. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7510–7514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hladik F, McElrath MJ. Setting the stage: host invasion by HIV. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:447–457. doi: 10.1038/nri2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash M, Kapembwa MS, Gotch F, Patterson S. Chemokine receptor expression on mucosal dendritic cells from the endocervix of healthy women. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;190:246–250. doi: 10.1086/422034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jimenez-Flores R, et al. High-risk human papilloma virus infection decreases the frequency of dendritic Langerhans’ cells in the human female genital tract. Immunology. 2006;117:220–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Witte L, Nabatov A, Geijtenbeek TB. Distinct roles for DC-SIGN+-dendritic cells and Langerhans cells in HIV-1 transmission. Trends Mol. Med. 2008;14:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valladeau J, et al. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores-Langarica A, et al. Network of dendritic cells within the muscular layer of the mouse intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:19039–19044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504253102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pudney J, Quayle AJ, Anderson DJ. Immunological microenvironments in the human vagina and cervix: mediators of cellular immunity are concentrated in the cervical transformation zone. Biol. Reprod. 2005;73:1253–1263. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hladik F, et al. Initial events in establishing vaginal entry and infection by human immunodeficiency virus type-1. Immunity. 2007;26:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagiwara H, Ohwada N, Aoki T, Fujimoto T. Langerhans cells in the human oviduct mucosa. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 1998;103:253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hladik F, et al. Dendritic cell-T-cell interactions support coreceptor-independent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in the human genital tract. J. Virol. 1999;73:5833–5842. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5833-5842.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain LA, et al. Expression and gene transcript of Fc receptors for IgG, HLA class II antigens and Langerhans cells in human cervicovaginal epithelium. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1992;90:530–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller CJ, McChesney M, Moore PF. Langerhans cells, macrophages and lymphocyte subsets in the cervix and vagina of rhesus macaques. Lab. Invest. 1992;67:628–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parr MB, Parr EL. Langerhans cells and T lymphocyte subsets in the murine vagina and cervix. Biol. Reprod. 1991;44:491–498. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz AJ, Alvarez X, Lackner AA. Distribution and immunophenotype of DC-SIGN-expressing cells in SIV-infected and uninfected macaques. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2002;18:1021–1029. doi: 10.1089/08892220260235380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poonia B, Wang X, Veazey RS. Distribution of simian immunodeficiency virus target cells in vaginal tissues of normal rhesus macaques: implications for virus transmission. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2006;72:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turville SG, et al. Diversity of receptors binding HIV on dendritic cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:975–983. doi: 10.1038/ni841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keenihan SN, Robertson SA. Diversity in phenotype and steroid hormone dependence in dendritic cells and macrophages in the mouse uterus. Biol. Reprod. 2004;70:1562–1572. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ildgruben AK, Sjoberg IM, Hammarstrom ML. Influence of hormonal contraceptives on the immune cells and thickness of human vaginal epithelium. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;102:571–582. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson BK, et al. Repertoire of chemokine receptor expression in the female genital tract: implications for human immunodeficiency virus transmission. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;153:481–490. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65591-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed SM, et al. Immunity in the female lower genital tract and the impact of HIV infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 2001;54:225–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varol C, et al. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:171–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merad M, et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naik SH, et al. Intrasplenic steady-state dendritic cell precursors that are distinct from monocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:663–671. doi: 10.1038/ni1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onai N, et al. Identification of clonogenic common Flt3+M-CSFR+plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1207–1216. doi: 10.1038/ni1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naik SH, et al. Development of plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell subtypes from single precursor cells derived in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1217–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginhoux F, et al. Langerhans cells arise from monocytes in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:265–273. doi: 10.1038/ni1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanisz AM, Kataeva G, Bienenstock J. Hormones and local immunity. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1994;103:217–222. doi: 10.1159/000236631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young WG, Newcomb GM, Hosking AR. The effect of atrophy, hyperplasia, and keratinization accompanying the estrous cycle on Langerhans’ cells in mouse vaginal epithelium. Am. J. Anat. 1985;174:173–186. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001740207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patton DL, et al. Epithelial cell layer thickness and immune cell populations in the normal human vagina at different stages of the menstrual cycle. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000;183:967–973. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.108857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaul R, et al. The genital tract immune milieu: an important determinant of HIV susceptibility and secondary transmission. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2008;77:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marx PA, et al. Progesterone implants enhance SIV vaginal transmission and early virus load. Nat. Med. 1996;2:1084–1089. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wieser F, et al. Progesterone increases the number of Langerhans cells in human vaginal epithelium. Fertil. Steril. 2001;75:1234–1235. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes GC, Thomas S, Li C, Kaja MK, Clark EA. Cutting edge: progesterone regulates IFN-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2008;180:2029–2033. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Martins SL, Peterson HB. Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review. Contraception. 2006;73:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasin B, et al. Theta defensins protect cells from infection by herpes simplex virus by inhibiting viral adhesion and entry. 2004. pp. 5147–5156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Quayle AJ. The innate and early immune response to pathogen challenge in the female genital tract and the pivotal role of epithelial cells. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2002;57:61–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(02)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pal S, Schmidt AP, Peterson EM, Wilson CL, de la Maza LM. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-7 in the modulation of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Immunology. 2006;117:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacNeill C, et al. Surfactant protein A, an innate immune factor, is expressed in the vaginal mucosa and is present in vaginal lavage fluid. Immunology. 2004;111:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2003.01782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keller MJ, et al. PRO 2000 elicits a decline in genital tract immune mediators without compromising intrinsic antimicrobial activity. AIDS. 2007;21:467–476. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328013d9b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNeely TB, et al. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor: a human saliva protein exhibiting anti-human immunodeficiency virus 1 activity in vitro. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:456–464. doi: 10.1172/JCI118056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNeely TB, et al. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity by secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor occurs prior to viral reverse transcription. Blood. 1997;90:1141–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang W, et al. Activity of alpha- and theta-defensins against primary isolates of HIV-1. J. Immunol. 2004;173:515–520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aberg KM, et al. Psychological stress downregulates epidermal antimicrobial peptide expression and increases severity of cutaneous infections in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3339–3349. doi: 10.1172/JCI31726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chong KT, et al. High level expression of human epithelial beta-defensins (hBD-1, 2 and 3) in papillomavirus induced lesions. Virol. J. 2006;3:75. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kluver E, et al. Structure-activity relation of human beta-defensin 3: influence of disulfide bonds and cysteine substitution on antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9804–9816. doi: 10.1021/bi050272k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang D, et al. Beta-defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang D, Biragyn A, Kwak LW, Oppenheim JJ. Mammalian defensins in immunity: more than just microbicidal. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hubert P, et al. Defensins induce the recruitment of dendritic cells in cervical human papillomavirus-associated (pre)neoplastic lesions formed in vitro and transplanted in vivo. FASEB J. 2007;21:2765–2775. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7646com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia JR, et al. Identification of a novel, multifunctional beta-defensin (human beta-defensin 3) with specific antimicrobial activity. Its interaction with plasma membranes of Xenopus oocytes and the induction of macrophage chemoattraction. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;306:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s004410100433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biragyn A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of dendritic cells by beta-defensin 2. Science. 2002;298:1025–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1075565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quinones-Mateu ME, et al. Human epithelial beta-defensins 2 and 3 inhibit HIV-1 replication. AIDS. 2003;17:F39–F48. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Funderburg N, et al. Human -defensin-3 activates professional antigen-presenting cells via Toll-like receptors 1 and 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18631–18635. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0702130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.LeVine AM, et al. Distinct effects of surfactant protein A or D deficiency during bacterial infection on the lung. J. Immunol. 2000;165:3934–3940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henning LN, et al. Pulmonary surfactant protein A regulates TLR expression and activity in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7847–7858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crouch E, Wright JR. Surfactant proteins a and d and pulmonary host defense. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:521–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crowther JE, et al. Pulmonary surfactant protein a inhibits macrophage reactive oxygen intermediate production in response to stimuli by reducing NADPH oxidase activity. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6866–6874. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brinker KG, Garner H, Wright JR. Surfactant protein A modulates the differentiation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003;284:L232–L241. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00187.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sato A, Iwasaki A. Induction of antiviral immunity requires Toll-like receptor signaling in both stromal and dendritic cell compartments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16274–16279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406268101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Minns LA, et al. TLR9 is required for the gut-associated lymphoid tissue response following oral infection of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 2006;176:7589–7597. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aflatoonian R, Fazeli A. Toll-like receptors in female reproductive tract and their menstrual cycle dependent expression. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2008;77:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fazeli A, Bruce C, Anumba DO. Characterization of Toll-like receptors in the female reproductive tract in humans. Hum. Reprod. 2005;20:1372–1378. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shen H, Iwasaki A. A crucial role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in antiviral protection by CpG ODN-based vaginal microbicide. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2237–2243. doi: 10.1172/JCI28681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rebbapragada A, et al. Negative mucosal synergy between Herpes simplex type 2 and HIV in the female genital tract. AIDS. 2007;21:589–598. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328012b896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gardner L, Moffett A. Dendritic cells in the human decidua. Biol. Reprod. 2003;69:1438–1446. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meylan E, Tschopp J, Karin M. Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature. 2006;442:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Recognition of viruses by innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2007;220:214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zammit DJ, Cauley LS, Pham QM, Lefrancois L. Dendritic cells maximize the memory CD8T cell response to infection. Immunity. 2005;22:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Quayle AJ, Pudney J, Munoz DE, Anderson DJ. Characterization of T lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells in the murine male urethra. Biol. Reprod. 1994;51:809–820. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.5.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Witte L, et al. Langerin is a natural barrier to HIV-1 transmission by Langerhans cells. Nat. Med. 2007;13:367–371. doi: 10.1038/nm1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Le Poole IC, et al. Langerhans cells and dendritic cells are cytotoxic towards HPV16 E6 and E7 expressing target cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2008;57:789–797. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0415-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, Engering A, t Hart BA, van Kooyk Y. Self- and nonself-recognition by C-type lectins on dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004;22:33–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Geijtenbeek TB, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jameson B, et al. Expression of DC-SIGN by dendritic cells of intestinal and genital mucosae in humans and rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 2002;76:1866–1875. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1866-1875.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gurney KB, et al. Binding and transfer of human immunodeficiency virus by DC-SIGN+ cells in human rectal mucosa. J. Virol. 2005;79:5762–5773. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5762-5773.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saphire AC, Bobardt MD, Zhang Z, David G, Gallay PA. Syndecans serve as attachment receptors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on macrophages. J. Virol. 2001;75:9187–9200. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9187-9200.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Witte L, et al. Syndecan-3 is a dendritic cell-specific attachment receptor for HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19464–19469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spiteri MA, Clarke SW, Poulter LW. Alveolar macrophages that suppress T-cell responses may be crucial to the pathogenetic outcome of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur. Respir. J. 1992;5:394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Greenhead P, et al. Parameters of human immunodeficiency virus infection of human cervical tissue and inhibition by vaginal virucides. J. Virol. 2000;74:5577–5586. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5577-5586.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Collins KB, Patterson BK, Naus GJ, Landers DV, Gupta P. Development of an in vitro organ culture model to study transmission of HIV-1 in the female genital tract. Nat. Med. 2000;6:475–479. doi: 10.1038/74743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leon B, Ardavin C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 2008;86:320–324. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sajic D, Patrick AJ, Rosenthal KL. Mucosal delivery of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides expands functional dendritic cells and macrophages in the vagina. Immunology. 2005;114:213–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu W, Kelly KA. Prostaglandin E2 modulates dendritic cell function during chlamydial genital infection. Immunology. 2008;123:290–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Parr MB, Parr EL. The role of gamma interferon in immune resistance to vaginal infection by herpes simplex virus type 2 in mice. Virology. 1999;258:282–294. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lund JM, Hsing L, Pham TT, Rudensky AY. Coordination of early protective immunity to viral infection by regulatory T cells. Science. 2008;320:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1155209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Freeman EE, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Su H, et al. Vaccination against chlamydial genital tract infection after immunization with dendritic cells pulsed ex vivo with nonviable Chlamydiae. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:809–818. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rey-Ladino J, Koochesfahani KM, Zaharik ML, Shen C, Brunham RC. A live and inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis strain induces the maturation of dendritic cells that are phenotypically and immunologically distinct. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:1568–1577. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1568-1577.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nagarajan UM, Ojcius DM, Stahl L, Rank RG, Darville T. Chlamydia trachomatis induces expression of IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 and IFN-beta independent of TLR2 and TLR4, but largely dependent on MyD88. J. Immunol. 2005;175:450–460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kammerer U, et al. Human decidua contains potent immunostimulatory CD83(+) dendritic cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;157:159–169. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64527-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rieger L, et al. Antigen-presenting cells in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle compared to early pregnancy. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2004;11:488–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laskarin G, et al. The presence of functional mannose receptor on macrophages at the maternal-fetal interface. Hum. Reprod. 2005;20:1057–1066. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nishioka Y, Nishimura N, Suzuki Y, Sone S. Human monocyte-derived and CD83(+) blood dendritic cells enhance NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:2633–2641. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200109)31:9<2633::aid-immu2633>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.King A, Wellings V, Gardner L, Loke YW. Immunocytochemical characterization of the unusual large granular lymphocytes in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. Hum. Immunol. 1989;24:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(89)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ban YL, Kong BH, Qu X, Yang QF, Ma YY. BDCA-1+, BDCA-2+ and BDCA-3+ dendritic cells in early human pregnancy decidua. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2008;151:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Heikkinen J, Mottonen M, Komi J, Alanen A, Lassila O. Phenotypic characterization of human decidual macrophages. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2003;131:498–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Osteen KG, Anderson TL, Schwartz K, Hargrove JT, Gorstein F. Distribution of tumor-associated glycoprotein-72 (TAG-72) expression throughout the normal female reproductive tract. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1992;11:216–220. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lessey BA, Pindzola JA. Tumor-associated glycoprotein (TAG-72) in endometriotic implants. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993;76:1075–1079. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.4.7682561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lidstrom C, et al. Cytokine secretion patterns of NK cells and macrophages in early human pregnancy decidua and blood: implications for suppressor macrophages in decidua. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2003;50:444–452. doi: 10.1046/j.8755-8920.2003.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Abrahams VM, Kim YM, Straszewski SL, Romero R, Mor G. Macrophages and apoptotic cell clearance during pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2004;51:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Denning TL, Wang YC, Patel SR, Williams IR, Pulendran B. Lamina propria macrophages and dendritic cells differentially induce regulatory and interleukin 17-producing T cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1086–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]